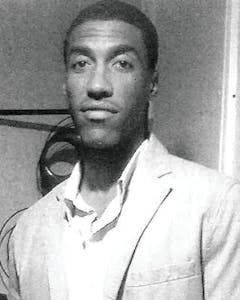

In September 2016, when FBI agents first started tailing Redrick “Red” Batiste, he seemed to be an ordinary young man leading an ordinary life. Batiste was 36 years old, tall and slim, with dark eyes and an easy smile. He lived with his two bulldogs in a two bedroom, 956-square-foot house in Acres Homes, a modest neighborhood twelve miles north of the skyscrapers of downtown Houston.

By most indications, he was exceedingly straitlaced. He dressed well, usually wearing pullover polo shirts and tightly belted cargo pants. Once a week, he went to a barbershop to get a haircut and a manicure. He was so meticulous about keeping his house clean that he asked visitors to take off their shoes before coming inside so they wouldn’t track dirt across the carpet. “Red even had the toilet paper coming out over the top of the roll,” said Tommie Albert, an older man in the neighborhood who’d known Batiste since he was a boy. “He said it looked better than toilet paper coming out from behind the roll.”

Batiste regularly visited his aging parents to check on them. A few times a week, he went to see his girlfriend, Buchi Okoh, their eighteen-month-old daughter, and Okoh’s five-year-old son from a previous relationship. Okoh, a striking, gregarious woman in her early thirties, worked in sales at a Cadillac dealership. On occasion, Batiste would take her to a nice restaurant, but most of the time they stayed home and played with the children. Okoh told friends that her boyfriend was a budding real estate developer, buying and renovating small homes. He was a good man, she said, intelligent and ambitious. He read self-improvement books like Do You!: 12 Laws to Access the Power in You to Achieve Happiness and Success, by the hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons. He was determined to make something of himself, “to be the best person he could possibly be,” Okoh said, “building his life the right way.”

Shadowing him around Houston in their unmarked cars, however, FBI agents weren’t convinced that Batiste was all that he appeared to be. They had begun to suspect that he was leading a secret life that Okoh, his parents, and his neighbors knew nothing about.

Red Batiste, they believed, was the leader of an armored car robbery ring, one of the most daring and diabolical the FBI had ever encountered.

A year and a half earlier, on February 12, 2015, a Brinks 500 series armored car arrived at the 22-story Capital One Plaza, on Westheimer Road, just blocks from the Galleria, the popular shopping mall. It was 1:45 p.m., a mild winter day with temperatures in the low 60s. A handful of office workers were lingering outside, enjoying the sunshine, a few of them taking smoke breaks.

The Brinks car eased into the building’s driveway and stopped directly in front of the Capital One bank on the ground floor. The car weighed approximately 25,000 pounds. It was essentially a massive, impenetrable locked box of hardened steel with bulletproof windows three inches thick. Inside were two Brinks employees: Bertha Boone, who had been driving armored cars for Brinks for nearly ten years, and Alvin Kinney, a sixty-year-old guard who had worked for the company since 1994. In armored car industry parlance, Kinney was known as the “messenger,” because it was his job to transport “coal bags” (canvas or plastic bags filled with cash) to and from banks, businesses, and ATMs. He wore a bulletproof vest and carried a high-powered handgun, which was holstered on his hip. That afternoon, he was stationed in the back compartment, where the money was stored.

When the car came to a stop, Kinney opened the back door, wheeled a metal cart onto a lift gate, lowered the cart to the ground, and shut the door behind him. Checking his surroundings, he pushed the cart into the bank. Twenty-five minutes later, he emerged with what authorities would later describe as “several bags of cash.” As he neared the Brinks car, three men wearing body armor and masks with face shields rushed toward him. Kinney shouted, but the men didn’t say a word. At least one of them lifted his rifle and fired at Kinney. Struck in the head, he fell to the ground, mortally wounded.

Boone set off the truck’s siren and then flung open her door, leaned out, and shot her handgun nine times toward the back of the car. Uninjured, the robbers returned fire, and Boone ducked back into the car. The robbers snatched the coal bags off Kinney’s cart, piled into a white Ford F-250 pickup truck that had backed up behind the armored car, and raced away.

Within minutes, Houston police officers and a team of FBI agents assigned to the Houston field office’s Violent Crime Task Force descended on the bank. (Armored car robberies, like bank robberies, are federal crimes.) They studied video from the bank’s surveillance cameras and also examined the Ford F-250, which was found in a parking garage a few blocks away. It had been stolen, and the robbers had abandoned it and switched to another vehicle. Later they interviewed a witness who had gotten a glimpse of the getaway driver: a young black man who wasn’t wearing a mask.

But the few clues led nowhere. Even when authorities offered a $100,000 reward, no helpful leads came in. The robbers had vanished.

Every year, there are between 25 to 35 attempted armored car robberies in the United States. By comparison, approximately 4,000 banks are robbed in the same span. There’s a simple reason for this glaring difference: there is far less peril in robbing a bank than an armored car. Most banks don’t have armed security guards patrolling the lobbies, and tellers will hand over money to robbers from their cash drawers, no questions asked—they’ve been taught that their own safety is paramount.

A criminal who robs an armored car, however, knows he’s putting his life on the line. Drivers and messengers for armored car companies are not paid to be amicable. “The employees have been trained to use deadly force the moment they believe they are in imminent danger of bodily harm,” says Jim McGuffey, a security consultant who spent 26 years working in the armored car industry. “That’s standard practice. They don’t have to wait for the robber to shoot first.”

Still, the greater the risk, the greater the reward. Bank robbers are lucky to escape with a few thousand dollars from a teller’s drawer, but it’s not unusual for a messenger to carry tens of thousands of dollars or more in the coal bags. Nor is it unusual for an armored car to carry several hundred thousand dollars in its back compartment. Typically, robbers try one of two approaches. They may try to break into the armored car itself, blocking its path with a truck or van and then attaching a small bomb or stick of dynamite to the back door, hoping to blow it open. More frequently, they go after the messenger, sneaking up behind him with their guns drawn, ordering him to forfeit his weapon, grabbing his coal bags, and then fleeing.

In Houston, the members of the FBI’s Violent Crime Task Force have dealt with just about every type of armored car robber. A few years ago they even arrested a Loomis guard and a Houston police officer for conspiring with a team of robbers to hijack an armored car, presumably in return for a cut of the loot. But Kinney’s brutal murder was a rarity: the first time since 2002 that a Houston armored car employee had died in the line of duty. And it was not just a killing. It was a cold-blooded execution. Kinney hadn’t even been given a chance to surrender.

Over the next year, there were two more armored car robberies in Houston. One was rather routine: two masked men pulled their guns on a messenger and snatched his coal bag at a supermarket. The second was another ambush.

On November 6, 2015, at around 2:00 p.m., a Loomis armored car pulled up to a Bank of America on North Shepherd, north of downtown, and a messenger exited the car. When he returned from the bank, a black man wearing a mask, a bulletproof vest, and a gray long-sleeved hoodie stepped out of a stolen white Jeep Patriot parked nearby. In his hands was a high-caliber semiautomatic rifle. Saying nothing, he sprinted toward the messenger, aimed his rifle, and pulled the trigger.

Although the messenger was hit several times, he was not critically injured, and he staggered back to the armored car. The gunman, realizing he wasn’t going to get to the coal bag, turned and darted toward a blue four-door sedan that was stationed on an adjacent street. He climbed into the passenger seat, and the car sped away.

This time, when members of the task force studied the bank’s video, they couldn’t believe what they were not seeing: the shooter.

Once again, the FBI task force arrived to conduct interviews and study surveillance videos. (The details regarding the task force’s investigation are based on affidavits from FBI agents, court records, testimony given at a hearing in a federal district court, and interviews with attorneys and other sources who have been briefed by authorities about the robberies and murders. An FBI spokesperson did not make agents available for interviews.) The task force likely wanted to know whether this shooter was the same one involved in Kinney’s death. And if so, why, this time, hadn’t he relied on any help other than a getaway driver? Had his Capital One accomplices backed out of this robbery, unwilling to risk being shot at again? Or was the Loomis shooter someone else entirely—a random Houston criminal with a rifle?

Hoping to generate a lead, the task force released a video to the public of the shooter opening fire, and a $15,000 reward was also offered for information leading to the arrest of the armed robber. But as with the Capital One heist, there were no tips worth investigating.

Then, on March 18, 2016, just a few minutes past noon, another Loomis armored car pulled up to a JPMorgan Chase branch on Airline Drive, in north Houston. The messenger, Melvin Moore, carried a cash-filled cassette intended for the bank’s outdoor ATM. But while reloading the ATM, he was struck by gunshots and collapsed to the ground. A black Nissan Altima, which had been idling in the parking lot, accelerated toward the messenger. A man in the back seat leaped out of the car to grab the cassette, but Moore, a 32-year-old married father of four young children, was still alive. He grabbed his handgun and fired at the man, who dived back into the Altima as it roared out of the parking lot. Moore dropped his gun to the pavement and died.

This time, when members of the task force studied the bank’s video, they couldn’t believe what they were not seeing: the shooter. Instead of trying to kill the messenger while charging him, the shooter had set up outside the range of the surveillance cameras, at least fifty yards away. There, like a sniper, he was able to peer through the scope of his rifle, take a few breaths to steady himself, and fire away. The task force deduced that, as soon as the messenger had fallen, the shooter must have calmly driven away in his own vehicle while his accomplices in the Altima screeched toward the ATM to grab the money.

This particular scheme was brutal—and efficient—like something out of a Michael Mann film. If Moore had died instantly, the scheme would have gone off without a hitch. Yet even then, the whole operation transpired so quickly, in a matter of seconds, that the driver of the armored car hadn’t been able to get off a shot.

The surveillance cameras didn’t capture the Altima’s license plate number or get a clear image of the man who had tried to snatch the cassette. And there was no evidence at all regarding the identity of the shooter. No one had reported seeing him fire his rifle or drive away. Although another $15,000 reward was offered, no one came forward with helpful information, and once more, the task force was confounded. All it could do was wait and see if the shooter and his crew ambushed another car.

The wait lasted five months and eleven days. On August 29, just before 6 p.m., outside of a Wells Fargo bank on Northwest Freeway, a 25-year-old Brinks messenger named David Guzman was preparing to place a new cassette into an ATM when gunshots rang out and he crumpled to the ground. A blue Toyota sedan quickly pulled up next to Guzman, and a masked man emerged from the back seat. He sprayed something on Guzman’s face, perhaps to cloud his vision. The robber grabbed the cassette from the dying Guzman and hustled back to the Toyota. Whenever the robbers pried open the cassette, they must have celebrated: it contained $120,000.

After the robbery, FBI agents were able to secure video from an outdoor security camera at an Extended Stay America hotel across the street from the bank. The footage was grainy, so license plates weren’t legible, but agents did notice a white Toyota 4Runner pulling into the hotel parking lot at 2:54 p.m., three hours before the shooting, and backing into a parking space so that the rear of the 4Runner faced the bank. It left the parking lot at 5:57 p.m., immediately after the shooting. During that three-hour period, nobody entered or exited the SUV.

Why, the FBI agents must have wondered, would someone park at a hotel, linger for several hours, and then drive away? Was the 4Runner involved in the robbery? Was the driver the man who’d shot Guzman? If so, why didn’t the hotel’s video show him getting out of the 4Runner with a rifle in his hands?

But that wasn’t their only lead. Someone came forward claiming to have inside information about the robberies. The task force had no doubt received calls from citizens motivated by the reward money, but curiously, this informant didn’t ask for the full $15,000 prize, instead agreeing to take $3,500 in cash in return for the promise of anonymity.

Intrigued, or because it had no other options, the task force agreed to the deal. The informant, who’d reportedly had a falling-out with Batiste over an undivulged slight, told them that the ringleader behind the robberies was a man named Red Batiste, a would-be real estate entrepreneur who lived in Acres Homes.

Acres Homes, a lower-to-middle-income community, is about nine square miles in size. It’s filled with old shotgun houses built on large, brushy lots, inexpensive apartments, and small homes in traditional subdivisions. Batiste lived in one of those subdivisions, on Tarberry Road, in a house with burglar bars over the doors and windows.

He was born in 1979, the only child of Roy and Joyce Batiste, and was raised just a few blocks outside Acres Homes. Roy, who’s now retired, worked as a Houston bus driver, and Joyce, who’s also retired, worked in the purchasing department for the computer manufacturer Compaq. They were devoted to their son, determined to keep him out of trouble. Most Sundays, they took him to Mt. Horeb Missionary Baptist Church, and they enrolled him in private schools from kindergarten through the seventh grade.

“He didn’t suffer for anything,” Joyce told me when I visited her and Roy. A kind woman with a soft voice, she sat at the kitchen table and sifted through a stack of photos of her son during his childhood: there was Batiste playing with a plastic race car track, strumming a small guitar, hugging his father, posing with his basketball team. On the kitchen wall was a poster-size photo of Batiste as an adult, eating barbecue and grinning. “We loved him, and he loved us,” Joyce said.

Still, Batiste had his troubles. According to his mother, it began during his high school years. In April 1996, a few months after his seventeenth birthday, he was arrested for unlawfully carrying a weapon, a misdemeanor for which he received a one-year probated sentence. A year later, he was arrested for misdemeanor assault (he reportedly got into a fight with a man who collided with his car), which led to a six-month stint in county jail. Over the next three years, he racked up a hodgepodge of other misdemeanors: possession of marijuana, driving while intoxicated, evading arrest in a motor vehicle, driving with a suspended license, evading detention, and another assault charge.

Yet people who knew Batiste said he wasn’t a hooligan. His girlfriend at the time was the daughter of pastors. (Now a pastor herself, she asked me not to use her name.) She said Batiste was charming, “a nice guy who laughed a lot.” In 1998 she became pregnant and gave birth to their son, who had severe medical problems. She and Batiste later broke up, and she was forced to sue him for child support. (Their son died, at the age of five, from ongoing health issues.) “Red was a little spoiled, and he had an irresponsible streak,” she said. “But he was young. We both were. I really believed he’d grow up and become a success.”

Batiste had a second child, a daughter, with another girlfriend, who also sued him for child support after they broke up. (The daughter, with whom he stayed in contact, is now in her early twenties.) In 2000, when he was 21, he was convicted in federal court and sentenced to six years in a federal penitentiary for making “false or fictitious statements in the acquisition of a firearm.” (Prosecutors claimed he had arranged for a female friend to purchase guns for him at a gun shop, which he then resold for a profit on the black market.) After being released on probation in 2005, he was arrested on a felony charge of credit card abuse (he had reportedly either used or sold stolen credit cards), which led to a twenty-month sentence in state prison. In 2009, when he was thirty years old, he was charged again with credit card abuse, which led to thirty more days in county jail.

Yet even then, no one considered him to be particularly dangerous. Vivian King, a Houston attorney who represented Batiste on some of his cases (she’s now a senior prosecutor in the Harris County district attorney’s office), told me that Batiste was “one of the most well-mannered clients I ever had, perfectly polite, always saying ‘yes ma’am’ and ‘no ma’am’ to me whenever we talked.” And curiously enough, after his 2009 conviction, he seemed to abandon his criminal impulses altogether. He went to work for his neighbor Tommie Albert, who ran a roofing, fencing, landscaping, and container delivery business. “What struck me about Red was that he was interested in so many subjects,” Albert told me. “He would sit at the computer for hour after hour, just doing general research. He’d read about everyone from Muhammad Ali to Dick Gregory. I once told him I had an uncle who was one of the first black pilots in Birmingham, Alabama, and he researched that.”

Albert, whose own son had been shot to death nearly twenty years earlier, hoped that Batiste would someday take over his business. But Batiste said he aspired to get into real estate. Besides renovating homes, he wanted to purchase empty lots on which he planned to open storefront businesses, everything from a beauty salon to a day care center to a snow cone stand. “He even had this idea of buying large shipping containers and converting them into small homes that he would put on his empty lots,” Albert said.

In 2013, on Valentine’s weekend, Batiste met Buchi Okoh at a party. A former college volleyball player, she was in her late twenties, and she too was determined to do something with her life: she had earned her real estate license before becoming a salesperson at Stewart Cadillac, in Midtown. Okoh told me she immediately liked Batiste because he wasn’t a “sweet talker.” He was “straightforward and to the point.”

In fact, soon after they met, he confessed that he had a criminal record. “But he said he wasn’t living that life anymore,” Okoh recalled. “He had wised up.” And she believed him. For one thing, Batiste didn’t look or act like a hardened felon. He dressed well and took care of his body; he didn’t smoke or eat junk food, and he seemed to have no interest at all in meeting up with friends at night to drink and party. He preferred playing chess or Scrabble on his computer, reading one of his self-improvement books, or watching Netflix with Okoh at home.

Okoh also admired the fact that Batiste was conservative with money. Occasionally he splurged on a date at an expensive restaurant, like Ruth’s Chris Steak House, and he took her on a few vacations—to Austin, Puerto Rico, and Las Vegas—but he wasn’t an extravagant spender. Even when they went to Vegas, he did little gambling. “He didn’t believe in getting money and blowing it all over the place,” said Okoh. “He thought long-term, not short-term.”

In the summer of 2014, Okoh became pregnant, and the following March she gave birth to their daughter, Imani. As opposed to how he’d acted in past relationships, Batiste was committed to Okoh. He moved her and the children into a home he had bought east of downtown. In addition to that house, which was appraised at $46,140, he also owned the two-bedroom house in Acres Homes, appraised at $57,030; another house appraised at $29,561; and a lot appraised at $7,458. According to Okoh, he talked of buying another house big enough for all of them and any other kids they might have someday.

“I’m not going to sit here and say we were rolling in the dough,” Okoh said. “But he was never like, ‘I’m so stressed, I don’t know what I’m going to do.’ ”

When I interviewed Okoh over lunch at one of her and Batiste’s favorite restaurants, the District 7 Grill, in Midtown, I asked if she knew of any reason why Batiste might have started robbing armored cars. Was it so he could buy that fourth house? Set up a trust fund to take care of Okoh and Imani, in case something happened to him? Was he in debt and feeling desperate?

Okoh stabbed at some shrimp pasta with her fork. “I’m not going to sit here and say we were rolling in the dough,” she finally said. “But he was never like, ‘I’m so stressed, I don’t know what I’m going to do.’ He was fine. He wasn’t pressed for anything.”

Okoh put down her fork and stared directly at me. She seemed to be holding back tears. “I’m confused and I’m torn, because it doesn’t make sense,” she said. “He wanted to build his life the right way, have a family, and that’s what we were doing. We were building our family and making sure our kids were okay.”

Nothing must have made much sense to the members of the Violent Crime Task Force either. When they studied Batiste’s rap sheet, they saw he hadn’t been convicted of a crime in seven years. His criminal past seemed to be exactly that—in the past.

And if agents had crept up to his house and peered through the windows, they would have been even more perplexed. Batiste kept his home spotless: “so clean that everyone thought he had a maid,” Albert told me. On a table in his living room was an expensive chess set, the pieces polished to a shine. In his bedroom closet, his shoes were perfectly aligned and his clothes were divided by category—shirts, pants, and athletic suits—with all the hangers arranged the same way. Was this fastidious man also carrying out vicious armored car robberies?

The informant was insistent. Although it’s unclear exactly what was said to the FBI, the informant apparently made Batiste out to be the modern-day equivalent of Pretty Boy Floyd. (During the early thirties, the dapper Floyd and his accomplices committed numerous violent bank robberies until he was shot dead by a group of lawmen led by the famous FBI agent Melvin Purvis.)

On September 3, the task force was granted a state court order to install a tracking device on Batiste’s Jeep Wrangler and to mount a hidden surveillance camera outside his residence in Acres Homes.

Four days later, the task force caught another break. Houston police officers with the department’s tactical unit, who had been briefed about the FBI investigation, were driving through the parking lot of Meadows on Blue Bell, a large apartment complex two miles from Batiste’s home. They spotted a white Toyota 4Runner, and when they ran a check on the vehicle, they discovered it had been stolen. They also noticed that a hole had been cut out of the 4Runner’s rear door. The opening, they realized, was just large enough to accommodate a rifle with a scope. All someone had to do was fold down the back seat, stretch out on his stomach across the back half of the cabin, poke his rifle and scope through the hole, and start firing. It was the perfect sniper’s lair.

A tracking device was placed on the vehicle, and on September 14, it showed the 4Runner being relocated to a different parking space in the complex. Around the same time, Batiste’s Jeep Wrangler had been tracked leaving his home and going to the parking lot. The FBI agents speculated that Batiste had moved the 4Runner so that an apartment employee wouldn’t identify it as abandoned or stolen and have it towed away.

The members of the task force were now certain that Batiste was their man. Yet they had a major problem. They still had no evidence to convict him of a crime. They had no proof that the 4Runner at the apartment complex was the same 4Runner that had been in the Extended Stay America parking lot during the August robbery at Wells Fargo. Nor did they have proof that Batiste himself had pushed his rifle through the hole in the back door and shot an armored car messenger.

After considering various options, they decided they had only one good play to make. They needed to catch Batiste and his crew in the act. They needed to catch them robbing an armored car.

For nearly three months, FBI agents tailed Batiste in his Jeep Wrangler and observed his home through the surveillance camera. He ran errands, got his weekly haircut and manicure, swung by to see his parents, walked his two bulldogs, and visited Okoh and the children. Except for the evenings when he dropped by the apartment complex to move the 4Runner, about every week or so, he seemed to be living a completely innocent life.

Batiste did occasionally meet with a 37-year-old Acres Homes resident named Nelson Polk. Polk had a lengthy criminal record, including two felony convictions for drug offenses and one conviction for firearms offenses. Batiste also met a few times with Polk’s 46-year-old uncle, Marc Hill, who lived near Acres Homes. Hill too was an ex-con; he’d been convicted of a drug charge and multiple assault charges.

If Batiste was indeed running an armored car robbery operation, Polk and Hill would have been ideal accomplices—veteran criminals who didn’t scare easily. But, like Batiste, the two men appeared to have gone straight. Polk, who had two children, did odd jobs around town. Hill owned several businesses: a gourmet popcorn store called Popkorn Krush, a cemetery cleanup operation, a welding shop, and a tractor company that hauled rocks and cleared lots. He and his wife, Varfeeta Sirleaf, a nurse who worked as an administrator for a hospice company, lived with their three children in a two-story home worth $294,065.

When I later talked to Sirleaf, she described her husband as “a loving man” who worked hard yet still found time to homeschool their four-year-old son. “I would know if he was committing any crime, and he most definitely was not,” she told me. She said that Batiste had come to their house a few times. “He dressed urban, very chic, and was quiet and attentive and so intelligent that I thought he had a college background,” she said. Once, Batiste talked to one of the older children about the Toni Morrison novel Beloved. On another visit, he bantered with Sirleaf’s brother about day-trading on the stock exchange. “If he was a killer of armored car guards, would he be acting that way?” Sirleaf asked me. “Red wasn’t a killer.”

The FBI, however, wasn’t swayed by the three men’s outward appearance. Hoping for a new lead, the task force got another court order to install a tracker on Hill’s Toyota Camry on November 8. Hill too did little of interest, until just before 8 a.m. on November 21. The tracking device showed him heading to an Amegy Bank on North Sam Houston Parkway, fourteen miles north of downtown, just off Interstate 45. Hill idled in the bank’s parking lot for three hours. Thirty minutes after he left, Batiste arrived in his Jeep Wrangler. He stayed until five that afternoon.

The next morning, at around eight, Hill again showed up at the Amegy Bank and stayed for two hours. Batiste arrived around eleven and stuck around for nearly seven hours. The following day, Batiste was in the vicinity of the bank at 8:20 a.m. At eleven-thirty, a Loomis armored car pulled up next to the bank’s outdoor ATM. Batiste watched as the messenger replenished the ATM with a new cassette. Forty-five minutes later, Hill returned, this time in another car he owned, a black Infiniti QX56. After the armored car left, Batiste and Hill drove to nearby Greenspoint Mall. Polk met them in his beat-up Chevrolet van.

From a distance, the task force watched the three men gather their vehicles together. They had a short conversation and then returned to the vicinity of the Amegy Bank. They traveled up and down nearby streets for a few minutes—it appeared they were plotting escape routes—and then they disbanded and went their separate ways.

The members of the task force were certain that a robbery was imminent. They met with prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office, who fast-tracked a hearing in front of a U.S. district judge. On November 29, the judge signed a Title III interception order that allowed the task force to tap Batiste’s cellphone.

That same day, a woman rented a black 2017 Jeep Cherokee from a Houston Enterprise Rent-A-Car. Either she or someone else drove it to Batiste’s home. As best as can be determined, no one with the task force was watching the video streaming from the surveillance camera at that hour. Unseen, the Jeep Cherokee pulled into Batiste’s garage, and the garage door shut.

The wiretap now activated, FBI agents listened in as Batiste, who was at home, talked to Hill, who was posted at the Amegy Bank. “Commissary pulling up,” Hill said. Batiste told Hill to use his phone to film the commissary. “You at the cool spot or the apartment?” he asked Hill. “At the apartment,” Hill replied.

A few hours later, Batiste dialed a number that FBI agents later learned was registered to 29-year-old Bennie Phillips, who lived northeast of Acres Homes, in the suburb of Humble. Like Batiste, Hill, and Polk, Phillips had been charged with various crimes: possession of marijuana, possession of a controlled substance, evading detention, unlawful carrying of a weapon, and aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon. He was not a talkative man. During his conversation with Batiste, Phillips mostly listened as Batiste vaguely described a problem. “I’m still struggling, man,” Batiste said. “I’m having trouble trying to copy this motherf—er.”

Batiste seemed to be uneasy. He told Phillips that he’d had to remind someone to remain alert while watching the bank. “I said, ‘Man, we got to be on point from woop-woop to woop-woop.’ ” Batiste also admitted that he was anxious and had been drinking to calm his nerves. “It’s just like all of my other missions, man. I got to have two shots every night, man, just to go to bed, bro.”

That afternoon, Batiste spoke again to Hill, telling him that he had finally solved his “problem” by using pliers and a towel. “I just bust the thing off of there and went and bought one that looked just like it,” he said. Later, he walked outside, opened the door to his garage, and drove away. But he wasn’t in his Jeep Wrangler. He was in the rented black Cherokee. He drove to the Amegy Bank and spent a few hours in the parking lot.

Then he did something that seemed to make no sense at all. He drove the Cherokee back to the Enterprise lot and turned it in. Another man picked him up, and they made their way back to Acres Homes.

At the Houston FBI offices, agents played the recordings of Batiste’s cellphone conversations over and over, trying to decipher what they could. “Commissary,” they figured, was code for an armored car. The “apartment” could be a reference to an apartment complex about sixty yards south of the bank—an ideal place for a sniper to set up and shoot a messenger. The “cool spot” must be another unidentified place around the bank, possibly a parking spot where Batiste’s accomplices would wait before grabbing the messenger’s coal bag after the shooting.

But other words and phrases were harder to translate. Batiste, for instance, used nicknames for certain men: Young Un, Unk, Little Bro, and Nephew. At one point, Batiste talked to someone about having Nephew use the “peckerwood.” “He could be in there little whip and just dip through there, you know what I’m saying?” Batiste said.

And then there was the conversation about Batiste’s attempt to “copy” something. Had Batiste done something to the Cherokee during the brief time it was in his garage?

On December 2, the day after Batiste returned the Cherokee to the Enterprise lot, FBI agents rented the same Cherokee and drove it to a prearranged location where technicians were waiting. They didn’t find a hole cut into the back door, but they did discover that only one of the Jeep’s two remote-entry key fobs was working. They also found a GPS tracking device under the front hood.

For the first time, Batiste’s plan became clear. Using pliers and a napkin, he must have removed one of the fobs from the Cherokee’s cable key chain and replaced it with a fake. By keeping an original fob, he could steal the Cherokee whenever he wanted without the theft ever being traced back to him. And the purpose of the tracking device? Simple. Batiste would now be able to locate the Cherokee when the time came to steal it. In fact, at any moment Batiste could check the car’s location and head their way to pick it up.

Batiste returned home and told Hill he had moved the “go-kart.” His voice was calm and confident. Everything was moving along as planned.

The technicians quickly got to work. They hid a remote-controlled video camera with a microphone inside the Cherokee. They also installed their own tracking device under the hood and added a kill switch that could be used to shut off the engine remotely. “It was like the Spy vs. Spy comic strip in Mad magazine,” an attorney close to the investigation told me. “Batiste comes up with a pretty smart plan to trick up a car so he can steal it. And the FBI slips in and tricks up the same car so they can catch him.”

At six the next morning, an FBI agent drove the Cherokee to the parking lot of a DoubleTree Hotel in south Houston, near Hobby Airport. Seven hours later, using his own tracking device, Batiste pulled into the parking lot in his Jeep Wrangler. A man wearing a hooded jacket emerged from a passenger seat, opened the door of the Jeep Cherokee, and drove it back to the Meadows on Blue Bell apartment complex, where the stolen Toyota 4Runner had also been parked.

Batiste returned home and told Hill he had moved the “go-kart.” His voice was calm and confident. Everything was moving along as planned.

Two days later, a Monday, Batiste took the Cherokee to an auto shop to have its windows tinted, and on Tuesday, he drove it to the Amegy Bank. For several hours, he staked out the parking lot. He then sent word to his crew. The mission was on for Wednesday, December 7.

That day, Batiste also talked briefly to Okoh on the phone. He told her he loved her. “I said, ‘Nothing is more important than what you and I have,’ ” Okoh recalled. “He got quiet and said, ‘Okay.’ ”

After he woke up the next morning, he called his old friend Tommie Albert to tell him he loved him and that he would see him soon. Just before ten, he headed for the bank. For this robbery, Batiste had decided that his two accomplices assigned to pick up the coal bag would use the Toyota 4Runner and that he would use the rented Cherokee. He also had decided that he would set up in the parking lot of the nearby apartment complex, with the front of the Cherokee facing the bank. Evidently, during his scouting trips, he had concluded that he didn’t need to drill a hole in the Cherokee’s back door. Instead, he would train his rifle out the driver’s side window, pick off the messenger with a quick volley of bullets, and make a quick exit.

Batiste checked in with other members in his crew. In addition to the two accomplices near the bank in the 4Runner, others were assigned to cruise the roads surrounding the bank, looking for cops. At eleven, one of them called Batiste to let him know the commissary was en route. Soon after, a Loomis armored car turned off the Beltway 8 feeder road and into the bank parking lot. The miniature video camera installed in the Cherokee showed Batiste taking a couple of breaths to calm himself. Then he murmured, “What the f—?”

A Houston Police Department armored personnel vehicle peeled out from behind a nearby building, took aim at the 4Runner, and rammed into it. The two men inside the SUV opened their doors and fled—one of them tossed a handgun into a dumpster—and SWAT officers gave chase. Other SWAT officers, who had been hiding in the apartment parking lot, flanked Batiste’s Cherokee, and one of them detonated a flash grenade. Batiste tried to drive away, but the kill switch had been activated, and the engine stalled.

Batiste had the chance to surrender. But without saying a word, he threw open the door of the Cherokee, stepped outside, and fired off at least one shot with his rifle, a .223-caliber AR-15 semiautomatic with a scope. A SWAT officer returned fire, hitting Batiste in the chest and leg. Batiste collapsed to the ground, took a few more breaths, and died.

The two men who had fled from the 4Runner were quickly surrounded. They were identified as Nelson Polk and Trayvees Duncan-Bush, a 29-year-old felon with prior convictions for aggravated robbery and evading arrest. Police stopped Hill in his Infiniti a few hundred yards from the bank. He was accused of working as a lookout for Batiste. Also accused of serving as lookouts were Batiste’s friend Bennie Phillips and a third man, named John Edward Scott, a 40-year-old unemployed laborer who had reportedly known Batiste since they were kids. The woman who had rented the Cherokee for Batiste was not arrested. Apparently she knew nothing of the robberies and had picked up the Cherokee as a favor to Batiste.

Okoh wasn’t arrested, but members of the task force showed up at her office, drove her downtown to the Houston Police Department, informed her that her boyfriend had been shot dead, and then fiercely interrogated her. She was terrified, but she was adamant that she’d known nothing about Batiste’s robberies. And if they had believed he was committing crimes, she asked the agents and detectives, why didn’t they arrest him earlier instead of waiting to shoot him at the bank?

Okoh said she was kept overnight in jail before being released. By then, the police and FBI had already swarmed Batiste’s house in Acres Homes, ripping the burglar bars from the front door and ransacking the rooms in search of guns and stolen money. (The FBI did not announce what, if anything, was found.) In federal court, lawyers for Polk, Duncan-Bush, Hill, Phillips, and Scott downplayed or denied their clients’ participation in Batiste’s robbery ring. In fact, Hill’s lawyers later claimed that, on the morning of the attempted Amegy Bank heist, Hill had just coincidentally happened to be in the vicinity of the bank, looking for a new location for a gourmet popcorn shop. But U.S. district judge Ewing Werlein Jr. was having none of it. He said that the evidence “revealed a startling conspiracy—not to threaten to kill in order to commit a robbery, but rather first to kill as the modus operandi of the robbery.”

The trials of Batiste’s five alleged accomplices have not been scheduled. So far there is no indication that any of them plan to plead guilty and testify about the extent of Batiste’s crimes. At a detention hearing, when asked about other robberies Batiste had carried out, Jeffrey Coughlin, a young FBI agent who had helped lead the investigation, remained cagey, declaring that the FBI “at this time” was only connecting Batiste to the two armored car robberies in March and August of 2016. However, shortly after the December shoot-out, Houston police chief Art Acevedo, who had been briefed on the FBI’s investigation, announced at a press conference that there was a “high probability” that Batiste was involved in all of the murders of Houston’s armored car messengers over the previous two years, including the shooting of Alvin Kinney, in February 2015.

Regardless of the number of robberies Batiste committed, members of the task force must have realized they were lucky to catch him when they did. In the same manner that he had tidied and organized his house, Batiste had planned his robberies meticulously, and he had made improvements with each mission. If not for the informant, the FBI might never have caught Batiste at all.

The biggest unanswered question about Batiste, of course, is why he decided, seemingly without provocation, to carry out such a barbaric crime spree in the first place. Was it purely a matter of greed—or was there something else that drove him? Was it possible, for instance, that Batiste was seeking revenge against banks because they wouldn’t loan him money due to his criminal record (or perhaps the color of his skin), thereby derailing his real estate ambitions? “You’ll never understand the frustration that can build up in a young black man trying to make it in this society,” Albert told me. “And yes, Red had that frustration, not getting loans.”

Albert also made a point of telling me that Batiste had grown increasingly upset over the years at police officers who randomly pulled him over, patted him down, pushed him to the ground, and jammed their knees into his back—simply because he was a well-dressed black man driving a nice Jeep. “He said they treat black people worse than they treat a damn dog,” Albert recalled.

But when I asked Albert if seething anger had inspired Batiste to rob and murder, he quickly replied, “Red didn’t commit those crimes.”

After a pause, he added, “Not the Red I knew, anyway.”

Okoh and Batiste’s parents offered similar responses: the Batiste they knew wasn’t a violent man. His mother, Joyce, said she wished I could have been at her son’s memorial service, at Serenity Mortuary. Mourners arrived early and swapped stories about the man they loved—how he sprayed perfume on a sponge and stashed it in his Jeep Wrangler so it would smell good, how he volunteered to help his neighbors set up their computers. On a table beside the chapel’s entrance was a copy of Do You!: 12 Laws to Access the Power in You to Achieve Happiness and Success, along with a plaque that he had kept in his bathroom. “Don’t measure the size of the mountain,” read the inscription. “Talk to the one who can move it.”

A pastor led the service, and a few friends came forward and delivered impromptu eulogies. “Not one person who spoke had one bad thing to say,” Joyce told me.

“He must not have been all that bad,” she said, as if trying to reassure herself. “He wasn’t all that bad.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated since publication to correct an error. An armored car messenger carries a “coal bag,” not a “cold bag.” We have also removed a name not critical to the piece at that person’s request.