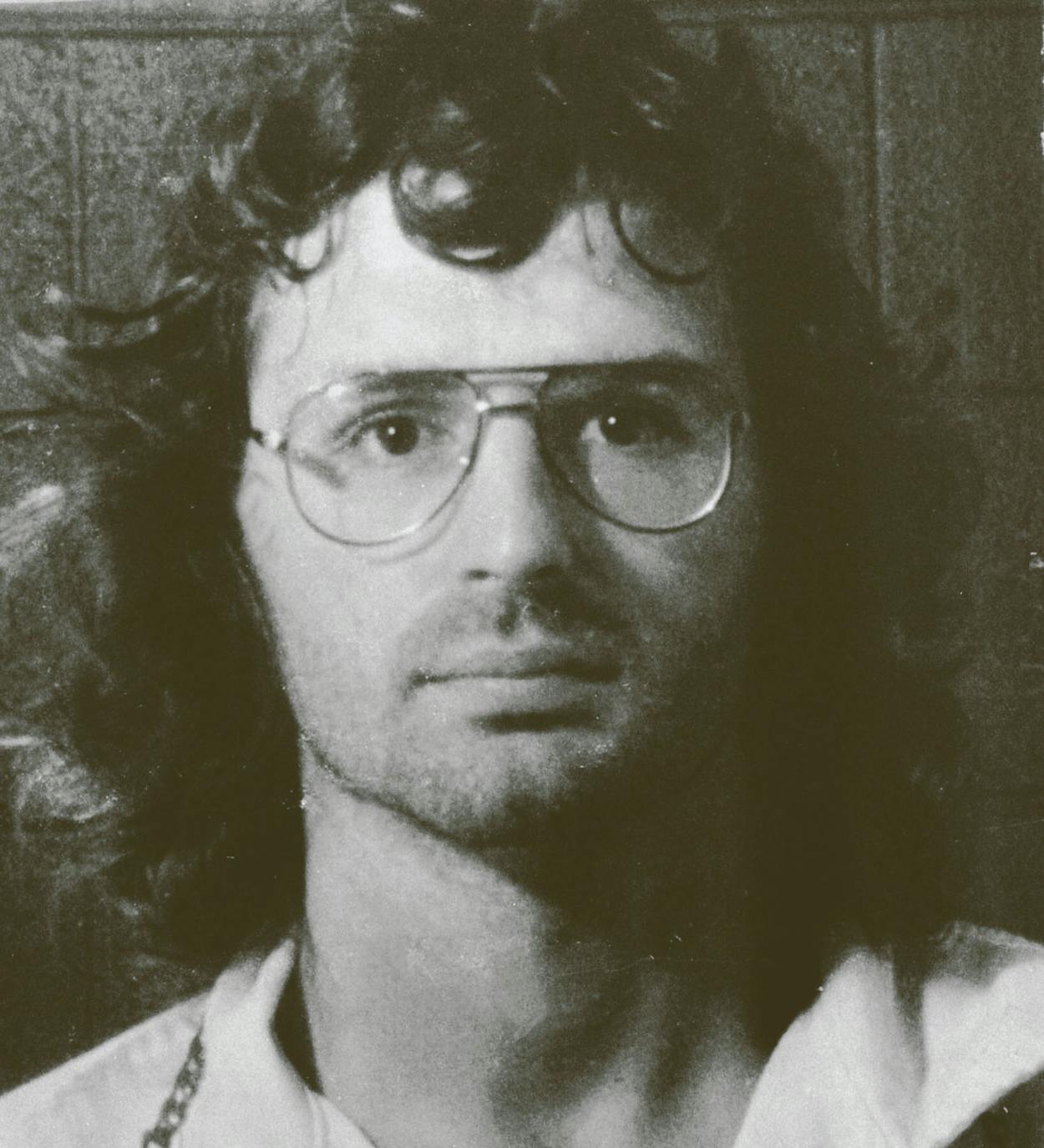

There are no signs that point the way to Mount Carmel. Past the chapel, which was built after the fire, all that remains are a few ruined outbuildings and a lonely stretch of prairie grass. It was here, ten miles east of Waco, that David Koresh prepared his acolytes for an apocalyptic confrontation between good and evil. His followers, a disavowed splinter group of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, believed themselves to be living in the end times, when God’s final judgment was at hand. A stuttering high school dropout with a gift for illuminating Scripture, Koresh preached the “New Light,” a self-styled gospel that required him to take multiple wives so that he could father enough children to sit on the 24 heavenly thrones described in the Book of Revelation. One of his wives was fourteen years old, another twelve. To his detractors, he was a false prophet, a con man, and a pedophile. To his followers, he was the messiah.

Life in the Branch Davidians’ austere two-story wooden dormitory revolved around strict discipline, healthy eating, physical labor, and rigorous study of the Bible. But in the summer of 1992, the group caught the attention of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms after a UPS driver reported delivering a package of dummy grenades to Mount Carmel. Koresh and other Davidians, who had been earning income for the group by working at weekend gun shows, had built up an arsenal of weapons, as well as an inventory of MREs (meals ready to eat), gas masks, and paramilitary gear that they called David Koresh Survival Wear. An ATF investigation suggested that the Davidians were also illegally converting semiautomatic weapons into fully automatic weapons. The agency, which was due for a congressional budget review in the spring of 1993, devised an elaborate plan to raid Mount Carmel that, it hoped, would net not only the sect’s illegal weapons but some positive publicity as well. And so Operation Trojan Horse was born. Rather than bringing Koresh in for questioning, the ATF trained its agents at Fort Hood to take the building by force.

In doing so, federal authorities inadvertently fulfilled Koresh’s prophecy of a pitched battle in which God’s people would be called to defend themselves. What ensued was the deadliest law enforcement operation in U.S. history. To mark the fifteenth anniversary of the standoff, we asked the people who were there to share their stories.

“‘They Know We’re Coming!’”

On the morning of February 28, 1993, ATF agents gathered at a staging area near Waco and prepared to serve a search warrant on the Branch Davidians’ residence. KWTX-TV cameraman Dan Mulloney, who had received a tip about the raid, headed for Mount Carmel with reporter John McLemore. A colleague, cameraman Jim Peeler, was supposed to meet them there but got lost. As Peeler studied a map by the side of the road, a mailman stopped to ask if he needed directions. Peeler did not know that the mailman was David Jones, a Branch Davidian who was Koresh’s brother-in-law.

Jones hurried back to Mount Carmel to tell Koresh of his encounter. Koresh then took aside Robert Rodriguez, a new devotee whom he correctly suspected was an undercover agent, and told him that he knew a raid was imminent. Rodriguez made a frantic exit and called ATF commander Chuck Sarabyn. “Chuck, they know!” he cried. Sarabyn, who would later claim that he was unaware that the element of surprise had been lost, decided to proceed with the raid anyway.

Larry Lynch, 61, was a lieutenant at the McLennan County Sheriff’s Office. He is now the county’s sheriff. I was at the staging area that morning when one of the ATF supervisors ran in and said, “Let’s go! Let’s go! They know we’re coming!”

Bill Buford, 63, was the resident agent in charge at the ATF’s Little Rock, Arkansas, office, whose agents—along with those from the New Orleans office—were called in to assist. He is now the bomb squad commander for the Arkansas State Police. I remember thinking, “What do you mean ‘They know we’re coming’?” Once we knew the element of surprise had been lost, we should have called it off. In hindsight, I wish that I had said, “No, I’m not taking my team.” I probably would have been fired, but knowing what I know now, I would have loved to have been fired for making that decision.

Chuck Hustmyre, 44, was an ATF special agent. He is a crime writer in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. There were 76 agents on the operation. Before we left the staging area, we were loaded up into cattle trailers. That was highly unusual, to say the least, but that part of Texas is just a big, barren, windswept prairie, and there’s nothing to hide behind. The idea was to get us to the door of the compound covertly and not announce that we were government agents. Somebody decided that cattle trailers blended in a lot better than a convoy of unmarked cars with tinted windows. So we were jammed, shoulder to shoulder, into two trailers that were covered in tarps so you couldn’t see in.

Buford: As I was getting people to put their gear on, I had a bad feeling. I asked, “What do you mean ‘They know we’re coming’? Are they getting ready for us?” I was told that all the Davidians were in the chapel, praying. My logic was, well, if they’re all in the chapel, maybe we can still get in there and cut the men off from their guns. We knew that they usually kept their guns in their living quarters, under their beds. I didn’t know that 45 minutes had elapsed since Robert [Rodriguez] had seen anything.

Clive Doyle, 67, is a Branch Davidian who was living at Mount Carmel at the time of the raid. He lives in Waco. I heard all this hubbub in the cafeteria, so I went back there to find out what the excitement was all about. People were saying, “We just heard there’s going to be a raid.” David [Koresh] walked in and confirmed that something was about to go down. He said, “I want everybody to go back to their rooms. Just stay calm.”

Buford: The information we had, which turned out to be true, was that the Branch Davidians were taking semiautomatic weapons and converting them into fully automatic weapons. They had also been converting practice hand grenades into live grenades. It was in preparation for the Armageddon that David Koresh had prophesied.

John McLemore, 44, was a reporter for KWTX-TV, in Waco. He is now the director of Internet communications for Conoco-Phillips in Houston. Dan Mulloney and I were at the intersection of the road that led to the compound when we saw three National Guard helicopters flying overhead. That was very unusual, so we got out of the car and started videotaping it. While we were standing there, we heard something rumbling down the road behind us. I turned around and saw two pickup trucks pulling cattle trailers that were covered with tarps. As they turned down the road toward the compound, we could see that they were packed with federal agents. We had been expecting ten or fifteen police officers—sheriff’s deputies or something—to make a couple of arrests and come out with some illegal weapons. This was bigger than anything we had imagined.

Hustmyre: I happened to be standing near a seam in the tarps, so I could see out a little, and as we rolled down the road toward the compound, I told the team leader, “It’s all quiet out here.” I mean, it was eerily quiet. I remember telling an agent near me, “This doesn’t seem right. This is spooky.”

“‘. . . That Last Exhalation of Breath, Like the Death Knell . . .’”

At 9:48 a.m., ATF agent Roland Ballesteros led the first team of agents off the trailers and approached Mount Carmel’s entrance, shouting, “Police! Search warrant! Lay down!” He pointed his shotgun in the direction of Koresh, who had answered the door, unarmed. Which side fired the first shot has never been determined. ATF agents say that a hail of bullets greeted them after Koresh slammed the door shut, while Branch Davidians claim that the ATF fired first, from either the ground or the helicopters above. The crime scene, which might have yielded answers, was later destroyed by the fire.

Hustmyre: Somebody in the back of the trailer threw the doors open, and we jumped out and rushed to our assigned positions. There was gunfire going off before my feet hit the ground. We were taking gunfire from multiple points inside the compound.

Doyle: David opened the front door, and the next thing I knew, he was yelling: “Hey, wait a minute! There are women and children in here!” And almost immediately there was a huge barrage of gunfire outside, and then all hell broke loose.

Catherine Matteson, 92, is a Branch Davidian who was living at Mount Carmel at the time of the raid. She lives in Waco. The windows were shot out, and there was glass all over the floor. You could hear bullets ripping through the walls. The women took the children into the hall on the second floor and put their bodies over them to shield them. This was war.

Sheila Martin, 60, is a Branch Davidian who was living at Mount Carmel at the time of the raid. She works at a day care center in Waco. My son Jamie—who must have been ten, I think—was lying under a window. He’d had meningitis when he was a baby, so he wasn’t able to walk or stand up or anything. It left him blind. And he was just lying there, with bullets coming in and glass falling on him. I remember thinking, “Is this how he dies? After all this sickness, is this how he leaves me?” When the gunshots stopped, I crawled to him on my hands and knees. As I reached him, the shooting started again. I carried him to the other side of the bed, where my two youngest kids were, and I pulled the mattress over us. He had blood around his mouth, and at first I thought that he’d been shot, but he’d gotten cut by all that glass. The poor little thing was just sitting there, in all that chaos, screaming, just screaming at the top of his lungs.

Doyle: The government tells it as though we were waiting for them in ambush, and then we just opened up and blasted the daylights out of them. That’s not true. If we had been waiting for them, they would never have gotten out of those trailers. Now, David had shown us in the Scriptures that it was okay to defend your family and your property. So after that huge barrage of gunfire, some people grabbed guns. Whether they already had them or whether they went and got them, I don’t know, but they retaliated.

Buford: Oh, it absolutely was an ambush. They had set up and were waiting for us to arrive. It was as intense as any ambush I was in when I was in Vietnam. Before I could even get out of the trailer, I was able to hear specific weapons, like AK-47’s and an M60 machine gun, which makes a very distinct sound. And we didn’t have any of those.

Hustmyre: We were trapped. It was just a big open field, and the only place to take cover was behind some junked cars in front of the compound. They could pick us off left and right. Once in a while I would hear an explosion. I found out later that they were chunking homemade hand grenades out the windows at us. Most of the agents were armed with only 9mm pistols, so we weren’t quite evenly matched.

Buford: The agents out front weren’t able to make entry because of the volume of gunfire. We went around to the side of the building, put ladders up, and made it onto the roof. One of the guys, Conway LeBleu, was shot almost immediately. Glen Jordan, Keith Constantino, and I broke the window of the Davidians’ arms room and stepped inside. Shortly after that, Glen yelled out that he had been hit. He was bleeding very badly. Rounds were coming through the walls, and I was returning fire.

McLemore: Mulloney and I were crouched behind a bus about fifteen yards from our news unit. The bus was being fired at from every direction. I can still recall hearing the sounds of gunfire and people screaming. One agent started yelling, “Hey, TV man! Run and call for help!” And I’m thinking, “Me? I’m fine right here behind this bus.”

Buford: Shots started coming up through the floor. The first round that hit me got me square in the butt and lodged in my thigh. I was trying to talk to Glen to find out if he could move, because we needed to get out of there. The next thing I knew, I’d been hit in the hip and the upper thigh with an AK-47. That knocked me down. Constantino covered us, and somehow Glen and I got out the window we had come in. I pulled myself down to the edge of the roof and rolled off. When I hit the ground, I broke a bunch of ribs. At that point, I thought I’d been shot in the chest.

McLemore: I took off from behind the bus and ran for the news unit, and there were bullets hitting everywhere. I called the station and got the news director on the phone and said, “It’s a war zone. Get every ambulance in the county out here.”

Buford: An agent who was assigned to our Little Rock office, Rob Williams, was about ten feet from me. He shot at a Davidian who had shot at me while I was lying on the ground. But in doing so they were able to see where he was, and he was shot and killed. Rob was a great kid. The next day would have been his twenty-sixth birthday. In Vietnam I saw a lot of people get shot, and the minute he was hit, I knew he was dead.

Byron Sage, 60, was the supervisory senior resident agent in the FBI’s Austin office and the bureau’s primary negotiator during the standoff. Now retired, he lives in Round Rock. Shots were still being fired when I got there. I went to the basement of the Waco Police Department, where their 911 consoles are, and Larry Lynch was talking on two different phones to people inside the compound, trying to secure a cease-fire. That was the first time I got to speak with David. I identified myself, and then I asked him, “Is it ‘Kor-esh’ or ‘Kor-esh’?” David said matter-of-factly, “Mr. Sage, have you ever heard a person die?” And I said, “Yes, I have.” He said, “Then you know how to pronounce my name.” I said, “What do you mean by that?” And he said, “It’s like that last exhalation of breath, like the death knell: ‘Koreshhhhh.’ He strung it out for a few seconds like that. I mean, the hair on the back of my neck stood up. It does even now, revisiting it. I looked over at Larry, and both of us shook our heads like, “We’re in for a hell of a ride.”

“‘Cease Fire!’”

Negotiations had begun minutes after the raid started, when Sheila Martin’s husband, Wayne, called 911 and pleaded with Lynch to ask the ATF to pull back. “Tell them there are women and children in here and to call it off!” he cried. Lynch tried in vain to reach ATF commanders, who did not respond. Thirty-one minutes passed before radio contact was established, and it was an hour before he could reach the ATF on a secure line.

The shoot-out lasted, on and off, for nearly two and a half hours, until Lynch secured a cease-fire at around noon. Each side agreed to hold its fire so the ATF could retrieve its dead and wounded. In the end, four federal agents and six Branch Davidians had been killed.

McLemore: About an hour passed and nobody moved. There was dead quiet, dead silence. And then in the rearview mirror, I saw an ambulance creeping toward us. It was just crawling along, going about five miles an hour. Apparently the Davidians had allowed the ATF to bring one ambulance onto the property to care for the wounded.

Hustmyre: Agents were yelling back and forth, “Cease fire! Only shoot if they shoot at you.” One of our guys, Eric Evers, had been bleeding in a ditch forever, and I said, “What are we going to do about him?” I think everyone was wondering if the Davidians were trying to lure us in to kill us, so nobody said anything. I said, “Hell, I’ll go get him.” A guy with an MP5 went with me. We sloshed through the mud until we reached a fence that extended about fifteen feet out from the compound, and when we looked around it, we saw two Davidians pointing their rifles right at us. I thought, “That’s it. We’re dead.” But they didn’t shoot. I left my pistol in my holster and kept my hands away from my side and yelled, “We’re supposed to pick up the wounded guy.” They started gesturing with their rifles and shouting, “Hurry the f— up!” Evers was still alive, down in this muddy ditch, and we pulled him out. We put his arms around our shoulders and walked him out of there. Once we got him to the road and I could see how many guys were wounded, I started to realize how bad things were.

Jim Peeler, 55, was and is a cameraman at KWTX-TV. I was standing by the side of the road when I saw a guy beating on a car, crying. He was dressed like a civilian. It wasn’t until later, when we were watching the video and we had found out more about the ATF’s investigation, that we realized it was Robert Rodriguez, their undercover guy. He was hitting the car and hollering, “I told them! I told them! I told them!”

Hustmyre: Someone got ahold of a black Chevy pickup, and we hauled ass back to the compound. The guy who was driving put it in reverse going about 30 miles an hour, and when he stopped, we loaded two dead agents into the bed of the truck. One of them was my partner from New Orleans, Todd McKeehan. I had just been asking where Todd was. I sat with him in the back of the truck, and his face was totally white.

Doyle: I was looking out the window when the ATF agents got up from their hiding places, and I couldn’t believe it. You know, I hadn’t realized how many of them there were. Later, I thought, “Oh, my God, we’re in for it. They’ll be back for revenge.”

David Thibodeau, 39, is a Branch Davidian who was living at Mount Carmel at the time of the raid. He now lives in Bangor, Maine, where he is a drummer in the rock band Phat Sally. Those guys had such pained expressions as they walked away. They couldn’t believe the outcome, obviously. They couldn’t believe they had lost. They were like, “What the hell just happened here?”

Peeler: Mulloney took his tape of the raid out of his camera and put it in his britches. He was street-smart enough to know that the ATF would want to confiscate it. Sure enough, some agents grabbed him and started smacking him—just beating the total crap out of him. Emotions were running really high. Sheriff Jack Harwell was standing there, and he said, “You SOB! I knew this was going to happen. Now, get out of here!”

McLemore: After the raid, Peeler and Mulloney and I were wrongly blamed for tipping off the Davidians. We were cleared by the FBI report a year later, and I even received a letter from the director of the ATF thanking me for assisting wounded agents that day. For a while, I was bitter about the whole situation, but I got past it and rarely think about it anymore. But it still haunts Peeler, and he did nothing wrong. Peeler is the nicest guy in the world, salt of the earth.

Peeler: The ones who should have felt the heat—the person who originally tipped off the media and the ATF commanders who led their agents in even though the raid had been compromised—they didn’t get the flak that we did. I was killed that day. You know what I mean, kid? I’ve never been the same since.

Matteson: David had been shot, and he was in bad shape. There was blood all over him. He was lying in the hall on the second floor, propped up on pillows, and he didn’t move for days. He was so white that I thought he was going to die.

Thibodeau: He was 33 years old, and he had been wounded in the side and on his hand. Yeah, we read some significance into that.

Bonnie Haldeman, 63, is David Koresh’s mother. She is a nurse in the East Texas town of Chandler. I was in the backyard when David called me, and he hung up before I could get to the phone, but the answering machine recorded it. He said, “Hello, Momma, this is your son. They shot me and I think I’m dying, all right? Tell Grandma hello for me. I’ll be back real soon, okay? I’m sorry you didn’t learn the [Seven] Seals, but I’ll be merciful to you, and God will be merciful to you too. I’ll see y’all in the skies.”

“They Came Out Two By Two.”

On March 1, the day after the shootout, the ATF officially handed over command of Mount Carmel to the FBI. More than 100 Branch Davidians were still inside. The bureau’s Hostage Rescue Team established a perimeter around the building, deploying sharpshooters and Bradley fighting vehicles. Negotiators immediately focused on getting Koresh to release as many children as possible.

Sage: The average length of a hostage-barricade situation in the United States is between six and eight hours. Worst-case scenario, we thought this might last three days.

Gary Noesner, 57, was in the FBI’s Special Operations and Research Unit in Quantico, Virginia, and was the negotiation coordinator for the first half of the standoff. He is now a crisis and security consultant in Fairfax, Virginia. We quickly realized that this was not a typical hostage situation. No one was being held against their will. It was very different than, say, a bank robbery, when a robber is holed up inside a bank and is threatening to harm customers if he isn’t given a getaway car. In that scenario, the success rate for law enforcement is very high, because the person came in to rob a bank; he didn’t come in to die. He’s hoping to leverage hostages to secure what he wants. The Branch Davidians were different. They were very devoted followers of David Koresh, and they didn’t want anything from the authorities other than for us to go away.

Martin: We prayed, and we tried to keep our hearts in a heavenly place. We believed that God was going to take care of us and that soon things would be better.

Noesner: The goal was to convince the Davidians that it was in their best interest to come out and that they would be treated fairly, with dignity and respect. That was a very difficult task, since the incident began with an extraordinary amount of bloodshed. So to come in on the heels of that very violent action and say, “Oh, forget about all that—we’re here to be your friends,” constituted the most significant challenge I’ve ever encountered as a negotiator.

Doyle: By the time the FBI had finished setting up the perimeter, the property was surrounded by snipers. We could see their sniper nests. If you went to the cafeteria and looked out toward the community of Elk, you could see them on the high point on the property behind ours. We counted seventeen agents on that ridge watching us.

Sage: David agreed to send the kids out if certain passages of Scripture were read over the radio. So whatever the designated passage was would be read on local radio, and as soon as the Davidians heard that, then kids were released. They came out two by two. Everything was biblical. By the third day, we had gotten eighteen kids out.

Noesner: They came out with little notes pinned to their jackets saying things like “Please send me to my aunt Sophie in Des Moines.” Well, we didn’t do that. The first thing we did was bring them to the command center. And we would say, “Let’s call your mommy and let her know you’re okay.” Koresh would usually let the moms get on the phone, and that gave us an opportunity to identify who they were, because we didn’t know who all was inside. It allowed us to convey the message we wanted heard, which was “We’re not here to hurt you.” Most importantly, we let them know that their kids weren’t going anywhere. We were waiting for them to come out and resume custody.

Sage: Some of those conversations were just heartrending. The kids would say, “Please come out,” or “Please come and get me!” Some of them were scared to death. Most of the negotiators were dads themselves, and these guys would push back their chairs and set these kids on their knees and try to make them feel less threatened.

Matteson: About five o’clock in the morning on March 2, someone woke me up and said that David wanted to talk to me. I went to see him and he said, “I made this tape, and I’d like you to take it so it can be played on prime time. I’ve made arrangements.” He said that he wanted the world to see that we were just Bible students.

Sage: David believed that he had unlocked—that he had been given, by God, the key to—the Seven Seals of the Book of Revelation. He put together this tape, and he guaranteed us that as soon as it was broadcast nationally, he would come out and bring everyone with him. Frankly, he thought he was dying, and he was milking it for all it was worth. This was going to be his parting message to the world. We required him, as part of the deal, to put a preamble on the tape that said he would bring everyone out peacefully once it had been played. I called the Christian Broadcasting Network, and it was on the air at nine or ten o’clock that morning. We started moving buses forward, and we put everything in place for the Davidians’ release. I was convinced that this was it.

Doyle: Quite a number of people had their bags packed. The plan was that we were all going to come out the front door, and David would be carried out on a stretcher.

Sage: Time passed, and David was upstairs praying. Noon came and still nothing had happened. We had more than one hundred people who were supposed to come out in three-minute intervals, so we needed to start moving. David’s top lieutenant, Steve Schneider, kept assuring us that everything was on track. He was telling us how the kids were all lined up and ready to go. He said that they had their winter jackets and their mittens on and were carrying some puppies in a box. But nothing happened. All of a sudden, a lightbulb went on that we’d been had. Steve either did not know that the deal was off or he was a very skillful liar, because he seemed genuinely embarrassed about the whole thing. It was getting dark when he finally went upstairs to talk to David. He came back and explained that David had said that God had told him to wait.

“David Was At the Center Stage of the World’s Media . . .”

As nearly four hundred federal agents stood at the ready, a makeshift media encampment, nicknamed Satellite City, sprang up two miles away. Meanwhile, two men—Houston resident Louis Alaniz and an itinerant named Jesse Amen—sneaked past the FBI barricades in hopes of hearing Koresh’s teachings. The Branch Davidians welcomed them in and taught them about Mount Carmel’s ascetic lifestyle, where Bible study remained the focus of each day.

McLemore: The networks arrived within hours of the raid. It might have been the first real cable-news media circus. We’ve had so many since then, but I guess that was the first. Over the first 24 hours, the media was pushed back further and further from the compound. We were told that it was for our own safety, because the Davidians had .50-caliber weapons that could reach us. From then on, all that we and the rest of the world could see was a long-distance view of the compound from more than a mile away.

Bobby Gilliam, 55, was the vice president of child care at the Methodist Children’s Home, in Waco, where many of the Davidian children lived for the duration of the standoff. He is now the organization’s president. TV news helicopters would fly over the Children’s Home, trying to get footage of the Branch Davidian children when they came outside to play.

Kenny Ray, 47, was a Texas Department of Public Safety sergeant who oversaw the seven roadblocks that the DPS set up around Mount Carmel. He is now a Texas Ranger in Tyler. People came to Waco from all over the country to see what was happening. They wanted to look around and take pictures. There were tourists and protesters—mostly libertarians and pro-gun types—and people who were just curious. Then there were folks who believed in Koresh. There’s one in particular I remember. He was in his late fifties, and he looked like a well-dressed businessman, with a coat and tie, driving a nice four-door sedan. He said, “I really, really need to get in and see Lord Koresh.” At first I thought there was going to be a punch line. But there was absolute sincerity on that man’s face. So I said, “Sir, you’re not going to be able to go past this point. The public can’t enter here.” He said, “You don’t understand. He is my Lord, and I’ve got to get to him.”

Sage: David was at the center stage of the world’s media and he ate it up. This was his launchpad to everlasting fame. He had been some obscure, wackadoo preacher on the high plains of Texas, and now all of a sudden he was, you know, the “messiah.”

Sam Howe Verhovek, 48, was a national correspondent for the New York Times based in Houston. Now living in Seattle, he is at work on a book about aviation history. There were reporters and photographers and video crews from all over the world. Many of us asked the federal authorities if we could go in there and talk to the Davidians and to Koresh, but we were told no, that we couldn’t possibly do that, because they couldn’t guarantee our safety. So we all shared a keen sense of frustration that no matter how close we were, we couldn’t breach that physical divide—to reach, literally, the other side of the story.

Doyle: There was no way of communicating with the outside world after the first day or so. The FBI closed that down real quick. The only outgoing line went to the negotiators. All the American public knew about us was what the FBI told them, which was that we were a “cult” and that we lived in a “compound.” As long as we were seen as a threat, then the situation was justified. The fact of the matter is that Mount Carmel has been misrepresented for years, long before David. When I first came to Texas, back in the sixties, rumors were being thrown around town that we had a nudist colony. There were accusations of child abuse down through the years. People said David was brainwashing us through deprivation and giving us only a cupful of peanuts a day.

Lynch: The sheriff’s office had gone out there on several occasions when there were reports of gunfire. They had a shooting range out there, so that wasn’t unusual. We also went out there with Child Protective Services. It’s my understanding that CPS never found anything because they never got past the entrance. They never got to sit down and do an in-depth investigation.

Thibodeau: Mount Carmel was a very monastic place. We lived in another time—an easier time, a better time. We didn’t have running water or most modern conveniences. But in a lot of ways, it was a very satisfying life. David’s message was incredibly deep, and it rang true with me. The more I learned, the more I felt like I was going through a transformation. I remember thinking, “These are mysteries that people have wanted to understand for centuries, and here I am understanding them.”

Matteson: David opened up the Bible to us. Sometimes he spoke so fast during Bible studies that I could hardly keep up with him. He was very intense. One time I sat and listened to him teach a Bible study for eighteen hours. I hated it when he stopped.

Louis Alaniz, 39, was a long-distance telephone service salesman in Houston. He is now an air-conditioning repairman in Westlake, Louisiana. I was sitting on the bus one day when I picked up a newspaper and saw a picture of the compound. I started praying about it, and I said, “God, if it’s your will, you provide the way.” I took a Trailways bus to downtown Waco and asked someone where the place was at. A man gave me a ride into the country, and from there it was probably only about two hours’ worth of traveling on foot. It wasn’t hard to get in. I just went through the woods and hid, and right at dusk, I ran across that open field and walked straight up to the compound. It had so many bullet holes in it it looked like a celestial star map. No one saw me until I knocked on the front door, and then a helicopter hit me with a spotlight. I started yelling, “Let me in! Let me in!” and someone finally opened up the door. Everyone inside wanted to know how I got there, and I was like, “Hold up, man. I just want to know—which one of you is David?”

“ . . . We were Playing Right Into their Hands.”

Desperate to win the trust of the Davidians and secure the release of more children, the FBI’s negotiation team sent in cartons of milk, a suture kit for Koresh’s wounds, and videotapes about themselves and their families. All told, negotiators engaged in 754 phone conversations with the Davidians. Meanwhile, the bureau’s tactical unit—the Hostage Rescue Team—pushed for a more aggressive approach. Its assault and sniper teams kept vigil over Mount Carmel, and as talks wore on, they adopted a confrontational stance that was at odds with negotiators’ conciliatory tone. Koresh, who was on the mend, continued to tell negotiators that God was telling him to wait. Waco, the joke went, stood for “We Ain’t Coming Out.”

Sage: The last child to come out of the compound left on March 5. Many of the kids who remained inside were David’s own children. We continued to press him for their release, and finally he said, “Hey, you don’t understand. These are my kids, and they’re not coming out.”

Doyle: The FBI bugged everything they sent into the building—the coolers of milk for the kids, the suture kit. One of our guys had an uneasy feeling, and when he started digging around inside stuff, he found listening devices.

Sage: We had no control over where those devices went inside the compound. For a while, we had terrific technical coverage of the trash pile. But what we were able to learn, after listening in, was that everybody was calm and content. There was no hysteria. And talking to David, it was clear that he was not a man in crisis. He was in his element.

Doyle: When we first went into this, none of us knew how long it was going to last. I don’t think any of us thought, “Let’s make them mad by staying in here for as long as we can.” But we had enough provisions to hold out for a long time. We had a walk-in refrigerator with lots of fresh and frozen food, and once our electricity was cut and we had to eat that food in a hurry, we started rationing MREs. We had enough MREs to last a year. Even though the helicopters had shot up all our water tanks, we still managed to get the drinking water we needed. We stuck buckets out of windows and in secluded areas around the building where we couldn’t get shot. Any rainwater that ran off the roof would fall into those buckets, and we rationed water to about half a glass a day per person.

Sage: We didn’t realize it until much later, but we were playing right into their hands. We were stalling for time, because in a classic negotiation, the passage of time is a good thing. Eventually, the individual who is in crisis realizes that the situation he is in is never going to end the way that he wants, that he is not in control, and that he is going to have to strike the best deal that he can. But what the Davidians were doing, I think, was stalling for time because David was becoming an international celebrity. It was about this time, if you’ll recall, that he was featured on the cover of both Time and Newsweek.

James McGee, 50, was an FBI special agent assigned to the Hostage Rescue Team. He is now a professor of risk and threat assessment at the University of Southern Mississippi, in Hattiesburg. Koresh routinely made himself openly visible to our tactical teams. He would literally sit on a window ledge and eat a bowl of ramen noodles, thumbing his nose at our sniper observers. At night, he liked to serenade us and play guitar solos. He was the king in his kingdom inside that compound, and he was in no hurry to come out.

Sage: The tactical commander, Dick Rogers, had made the decision that his guys didn’t need to know what the negotiators were doing. He thought that it wasn’t any of their damn business. Their job was to keep their eyes on target and be ready to engage any hostile force that should exit the compound. So they never understood what we were trying to do. While they were lying in a bar ditch in March freezing their asses off, they thought we were a bunch of weak sisters who were back at the command post with, you know, the fireplace crackling. They thought that we had gone over to the dark side, that we sympathized with the same people who had just murdered four federal agents. At one of the tactical sites, I remember someone wrote inside a Port-A-Potty, “Sage is a Davidian.”

McGee: Koresh was a master manipulator. He was pulling all the strings. The tactical team’s perspective was “Here is how a negotiator can best serve us: Convince Koresh to step in front of that window, and then the sniper will take care of the rest.”

Sage: All told, the negotiation team got 36 people out, including 21 kids.

Thibodeau: There was a period of time when the negotiations were pretty harmonious. I thought the FBI was being reasonable with David, considering everything that had happened. But at a certain point we realized that their word meant nothing. The negotiators would tell us one thing, and the guys in the tanks would do the exact opposite.

Doyle: The FBI was mooning our women from the tanks, dropping their pants and giving them the finger and all of that kind of stuff. That made a lot of people upset.

Noesner: Effective negotiations ended, I believe, on March 23. That was the day the last adult came out. Nine people had come out over the span of two days, and it was a remarkable time for the negotiation team. I mean, we weren’t exactly ready to open champagne bottles, but we finally felt that what we were doing was working. In the wake of that, inexplicably, the tactical team went forward with tanks and crushed cars and knocked over water towers. The on-scene commander thought that Koresh had not let enough people out. You should reward positive behavior, not punish it—that’s Psychology 101. Yet that’s what happened. Negotiations continued, but in reality, the chances that we would succeed had become so slim by then that our goals had become almost unachievable.

“‘Flames Await.’”

Hoping to make life so uncomfortable for the Davidians that they would have to leave the compound, the Hostage Rescue Team—against the wishes of negotiators—was allowed to begin engaging in psychological operations. Defense attorney Dick DeGuerin, whom Koresh’s mother had asked to represent her son, was allowed past the perimeter and into Mount Carmel in hopes that he could broker a surrender plan. The decision—to allow a defense attorney into an unsecured crime scene where federal agents had been killed—was unprecedented. Inside the building, conditions were deteriorating.

Doyle: Toward the end of March, they started trying to disrupt our sleep. They shone bright lights into the building all night long and blasted stuff over the loudspeakers: reveille, Tibetan monks chanting, Nancy Sinatra singing “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’,” even some Christmas carols. They slowed songs down and then sped them up so they sounded distorted. They played telephones ringing and babies crying and rabbits being slaughtered. Once, they made a recording of a helicopter that had been buzzing the building the day before. They played that over and over, and I kept instinctively flinching and ducking my head down, even though I knew the helicopter wasn’t actually there.

Ray: There we were, out on that rolling prairie, surrounded by farms that had been handed down from generation to generation. There were cows and horses and swing sets in people’s backyards and little red wagons out on front porches. And then there were these gigantic spotlights and these speakers blaring and these armored personnel carriers barreling around this pastoral setting. I’ll tell you, it was completely surreal.

Noesner: The Davidians believed in a confrontation between good and evil, and of course Koresh and his followers’ interpretation was that they represented the righteous and the good and that the authorities were agents of evil. They looked at themselves as martyrs.

Thibodeau: Scripture talks about how, in the latter days, the Beast will war against the people of God and destroy them—or, basically, exactly what was happening to us. Everything that David had been teaching us was actually taking place. It did seem like prophecy was being fulfilled.

Doyle: We had hardly any water for bathing, and we were all getting pretty rank. We had to use five-gallon buckets to dispose of our waste because we couldn’t go outside to our outhouses. I was getting one, maybe two hours of sleep a night.

Thibodeau: If I had been on the outside while this was going on, I would have been the first person to say, “These people are nuts, man! What are they doing staying in there? It’s time to come on out.” But having been there, I can’t say that. I challenge any American family to think about what they would do if they were invaded by a hostile force. If tanks pulled up outside their house and there were armed men inside, would they send their kids out? A lot of Americans would fight that to the end.

Sage: We pleaded with them every single day, for 51 days. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, they had the option of coming out. And they never did.

Dick Deguerin, 57, was and is a criminal defense lawyer in Houston. The Bradley stopped about a hundred yards away from the compound, and I got out and grabbed my briefcase and walked to the front door. As I walked, expended shells were literally crunching under my feet. They were everywhere: 9mm’s, .223’s, .45 calibers. Wayne Martin and Steve Schneider cracked open the door, which was barricaded by an upright piano and a bunch of cases of canned food. I stood on the front step—as the FBI had ordered me to do—and talked to them, and then David, for a few hours, about the situation they were in. David had interesting questions about what would happen if they surrendered and whether they would be able to practice their religion. Even though he knew that he would have to stand trial and might be convicted, he understood that his writings, his beliefs, his teachings would get exposure. He was self-centered enough to want to survive.

Sage: On April 14, David announced that he was going to start writing a manuscript about the Seven Seals, and he promised that once he completed it, he would surrender. He said it would take him approximately two days per seal. So he and Dick DeGuerin started beating a drum about giving him another two weeks. Well, we would have given him two weeks and beyond, but because of all his false promises, we wanted to hold him accountable. We told him that we would send in typewriters and whatever else he needed but that we needed to see proof—tangible, physical proof—that he was writing the manuscript. Four days later, Schneider, who was supposed to be editing it, told a negotiator that he hadn’t even seen the first page. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. If we could have been provided with any tangible evidence that David was living up to his promise, we would have given it as much time as it took.

McGee: About a week before the end, I saw a sign hanging in a window of the compound, and I reported it back to the command post. I thought it was a little unusual. There had been signs in the windows before, asking for the media and things like that. But this sign was different. It said “Flames await.” Someone had drawn big flames around the words in Magic Marker. They had taken their time drawing that sign.

“. . . A Voice from Upstairs Yelled Out that the Building was On Fire.”

The FBI devised a plan to bring the standoff to an end: The Hostage Rescue Team would flush the Davidians out of the building with CS gas, a type of tear gas. When newly sworn-in attorney general Janet Reno balked at the idea, she was assured that the plan was safe and the situation required urgent action because of ongoing—but never substantiated—child abuse. On April 17, she approved the operation. Mount Carmel was a firetrap: Hay bales barricaded doors, and fuel was on hand for the numerous Coleman lanterns that lit the building. But the FBI had no contingency plan if a fire broke out.

Just before dawn on April 19, Byron Sage called Mount Carmel and reached Steve Schneider. Sage informed Schneider of what was about to happen, giving the Branch Davidians one last chance to surrender. Schneider hung up on him.

Doyle: About six o’clock in the morning—it was still dark outside—the FBI made an announcement over the loudspeakers that they were going to start gassing the building. That woke quite a few people up. Everyone hurried to find gas masks.

Thibodeau: The tanks started moving into position and surrounding the building. Then the loudspeakers came on and a voice said, “It’s time to come out with your hands up. The siege is over. David, come on out.”

Sage: The Davidians opened up on those tanks with everything they had. So many rounds were bouncing off them that they looked like they had been rigged with sparklers. I could see muzzle flashes inside the compound. We ended up taking a couple shots in the location where I was, right across the road. One went through the garage door and lodged in the wall, right on the other side of where I was standing.

Thibodeau: I heard a news report on the radio that morning that said we had fired on those tanks, and I knew that was a blatant lie. That’s when I lost hope and thought that those were the last hours of my life. I was sure that we were being set up.

McGee: They were firing at us with everything in their arsenal. I was in one of the Bradleys, and the rounds were coming at us in bursts—you know, rat-a-tat-tat-tat—so I knew they were shooting fully automatic weapons. I was lobbing CS gas rounds back at them. Anytime I heard or saw a report from a window, that was where I aimed. I fired 96 rounds, I believe. Now, keep in mind that an M79 is capable of firing a 40mm round of liquid CS gas that will penetrate a sheet of plywood from one hundred meters. So if it hit somebody . . .

Sage: Hours went by and no one came out. I was absolutely astounded. We wondered if they weren’t able to get out of the building because they had barricaded the doors. So the decision was made to penetrate further, both to make sure that the tear gas was inserted all the way into the building and to open up exits to allow people to come out.

Doyle: No one was leaving for one reason: We didn’t trust the FBI. They had told us over and over again that nobody was allowed to come out of the building without setting it up with the negotiation team first. Anyone who violated that rule had gotten a flash-bang grenade thrown at them and had the daylights scared out of them. The FBI had told us that their snipers needed advance warning of any movements that we might make. So there was always that threat that if you made one false move, you were dead.

Thibodeau: I honestly felt that I would be shot if I exited the building. I mean, I didn’t leave until the wall next to me caught fire later that morning and I could hear my hair crackling. That’s when I decided that I would rather be shot than burn to death.

Doyle: The gas looked like this misty kind of stuff, and it burned like crazy if it got on your skin. It stung like battery acid. I saw grown men crying from it.

Sage: All morning we kept giving specific instructions over the loudspeakers: “Come out the front door, turn left, walk down the driveway, come out one at a time.” But no one came.

Doyle: At some point that morning, David sent word around to the mothers that they should bring their children down to the first floor and go into the vault, a concrete structure whose door had been removed so the space could be used as a pantry. Whether David thought that the vault would protect them from the gas, I don’t know. He knew we didn’t have any gas masks that fit children and infants.

Sage: I had endorsed the plan to insert tear gas into the compound, but I had not entered into that decision lightly. We all knew that backing that kind of plan would subject the kids inside to a very distressing environment. But it was a hell of a lot less distressing than opening fire on the compound in a tactical assault. We believed that when the tear gas was inserted, mothers would move heaven and earth to get their children to safety and bring them out. We grossly underestimated the control that David exerted over them. The maternal instinct was what we banked on, and we were wrong.

Doyle: Around noon, a voice from upstairs yelled out that the building was on fire.

Sage: I looked over at the monitor, and I could see what appeared to be the first whiffs of smoke coming out of the south tower. I repeated the same instructions into the mike: “Those of you who are still inside, attempt to exit by any means possible. Walk toward the voices. Exit in any fashion that you can.” And still no one came out. No one. It was a sickening feeling. Once I saw the flames, my requests became pleas: “David, please don’t do this. Don’t end it this way. Save your people. Lead them out.”

McGee: The winds were blowing hard across the plains that morning. That building was mostly made of plywood—it was a tinderbox. I said to one of the guys, “This place is going to be consumed in twenty minutes.” That’s about how long it took. They kept the firefighters back for fear that they would be fired upon and let it burn.

Doyle: The tanks had made a hole in the wall of the chapel, and I stood there with David Thibodeau, looking out at the tanks, wondering, “Well, if we jump out, will they shoot us?” I don’t know how many seconds of hesitation there were, but as we were standing there deciding what to do, all this smoke drifted down into the south side of the building. When it reached the hole, it got sucked in and everything went totally black. I couldn’t see anything, but I felt this intense heat over my head, like a huge weight that was pushing me to the ground. I could hear people screaming behind me, and I knew who they were; I recognized some of their voices. That galvanized me to move.

Thibodeau: I jumped out of the hole, and when I turned around, I saw Clive coming out after me. He was patting his arms because they were on fire. I heard a big explosion behind me, and I saw the building falling in on itself. Only nine of us got out.

Sage: I had to turn my back to the monitor, because I needed to remain focused on what I had to do. I kept repeating instructions over the loudspeakers until 12:35 p.m., when the central tower imploded. Then I called in to the negotiation center. And I’ll tell you, that was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever had to do, because I had to admit that we had failed. I said, “Negotiations officially terminated at 12:35 p.m.”

McGee: I saw a Davidian jump out of a second-story window, and as soon as she hit the ground, I saw her stand up and run back inside the building. So I ran in after her. I found her inside, lying facedown on the concrete slab. I grabbed her and said, “Where are the kids?” Things were burning all around us, and there wasn’t much time left. I asked her again, “Where are the kids?” She was completely nonresponsive. She wouldn’t give me an answer. She looked at me like, “I’m not telling you anything.”

Noesner: The Branch Davidians were seeing Armageddon. In their view, our actions validated David Koresh’s end-of-the-world prophecies that he’d been telling them about.

Sage: I was in a daze. I walked outside, and I could feel the heat radiating on my face from two hundred yards away. The building was collapsing in on itself and being reduced to about eighteen inches of rubble. I stood there and watched that place burn. I’ll never forget the stench and the heat and the magnitude of that moment. Rounds were cooking off, and there were explosions every now and then. Ultimately we found that all the kids inside had perished. I don’t give a damn about the parents; it was their decision to stay inside. They’re responsible for it, and I can live with that. But my God. To have intentionally allowed those kids to die is unconscionable. There’s a special place in hell for David Koresh.

“We are Still Waiting for the Resurrection.”

Seventy-four Branch Davidians died on April 19, 1993. The enormity of the loss spurred questions that are still being debated: Did the Davidians commit mass suicide, as the FBI claims? Or did the bureau’s actions spark the blaze—either when its tanks knocked over lanterns or when two pyrotechnic tear-gas grenades, which were later discovered in evidence, were fired into Mount Carmel?

Ray: Before the fire had even begun to cool, the feds just disappeared. I was going down this road pretty close to the compound to check on some of my troopers, and something up ahead looked like it was sitting in the road. I came over this little rise, and I saw that it was an armored personnel carrier that someone had left there, with the keys in it and everything. Someone had just gotten out of it and walked away.

Sage: I didn’t leave Waco until May 6. I helped locate and exhume bodies. Some of them were the people who I had talked to for 51 days. That might sound crazy, but I had to work through it. I just couldn’t make sense of what had happened.

Dr. Nizam Peerwani, 61, was and is the Tarrant County chief medical examiner, in Fort Worth. His office performed autopsies on the fire’s victims. David Koresh had a gunshot wound to the forehead. His associate Steve Schneider had a gunshot wound to the mouth, and we found multiple people who had similar gunshot wounds. There was one person, I can’t recall his name, who had a gunshot wound to the back. So there were people who were shot or who asked to be shot. I can’t be absolutely sure as to what the scenario was when all this happened.

Lane Akin, 55, was a Texas Ranger who assisted with the fire investigation. He works in corporate security in Dallas. At that point, I was no fan of the FBI, so if for some reason you could point the finger at them—if there was evidence there—I dang sure would’ve done it. But it was obvious that that fire was started on the inside, and I get aggravated to this day when I hear people saying otherwise. You could see that the sides of the Coleman fuel cans we found had been stabbed with a knife and vented so the fuel would come out faster. We picked up at least twenty of those. They wanted to pour that fuel out in a hurry because it was the end. We were able to determine that fires broke out in three different locations at basically the same time, so it was obvious that Koresh was manufacturing his own Armageddon.

Matteson: We didn’t start any fire! The fire was set by the government.

Thibodeau: Until one of the survivors who was there tells me that they lit the fire, I’ll never believe that we started it. Because where I was, that didn’t occur.

Sage: I ended up reviewing all the audiotapes that our concealment devices recorded on April 19, and there are 47 times when the Davidians mention spreading the fuel: “Do you have more fuel?” “I need some Coleman over here,” and so on. Now, we didn’t hear these tapes in real time; if we had, I’m confident that we would have changed course. Right after Steve hung up on me on the nineteenth, there was a clear order: “Spread the fuel.” The last recording on that mike is also, I’m convinced, Steve, and he says, “Start the fires.” This is not us trying to make up some story. These are actual audiotapes of Davidians inside the compound.

Peerwani: We found the women and children huddled together, under blankets. There were 27 bodies, two of them pregnant women. They were covered in debris—not just construction debris but spent rounds of grenades and ammunition. I suspect that the blankets were moist, to try and keep out the smoke. But there was such a rip-roaring fire that they were trapped. That was the most profound and distressing aspect of this entire case. To see that mass of human remains was a horrific thing for all of us.

Martin: My oldest son, he was twenty. His name was Wayne Joseph Martin. Anita Marie Martin, she was eighteen. Sheila Renee Martin, she was fifteen. And Lisa Marie Martin, she was thirteen. She was the hardest one. At the Salvation Army, we were watching TV when the building burned to the ground. Afterward, someone asked me the names of my husband and children. When I got to Lisa, I saw her face and I realized that she was gone. I had left Mount Carmel in March to care for my youngest ones, and the older kids had stayed there with their father.

Buford: Initially, I think the public was very much on our side. As time went on, it seemed like the media only reported that the Davidians were just good Christian people who had wanted to be left alone, that they would have gladly surrendered their arms if we had only asked them. I don’t believe that would have been the case. When public opinion turned, it felt like when I came home from Vietnam. We had become the enemy, or at least in the media we did. It was hard because all you heard about was poor Koresh. No one talked about Rob Williams’s wife and his mom and daddy or Conway LeBleu’s kids or Todd McKeehan’s folks and his wife. It just seemed like they were forgotten.

Charles Pace, 58, is a Branch Davidian who was living in Alabama at the time of the standoff. He is now the trustee of Mount Carmel. This is a historic site, but the city of Waco doesn’t want anyone to know where it is. There’s no information downtown about how to get here. There are no signs or memorials. People find us anyway; not a day goes by that we don’t have visitors, and they come from all over the world. But the city wants to forget what happened here. They’re planning to run the Trans-Texas Corridor right through here and pave us over.

Balenda Ganem, 56, is David Thibodeau’s mother and a teen counselor in Bangor, Maine. Many of the Davidian children’s remains went unclaimed because whole families were dead or their relatives were too poor to pay for funeral services or no one wanted them. And so all those bodies that had been at the coroner’s office were buried, without markers, in paupers’ graves in a Waco cemetery.

Martin: We had to stand behind the caution tape. We watched them bring out coffin after coffin and drop them in the ground. It was a horrible thing.

Doyle: Some of us have stayed in Waco. A few of us meet once a week to have Bible studies. And we wait. We are still waiting for the resurrection. It’s not just David who will be resurrected but all our people who died. I consider them martyrs, you know.

Haldeman: I have my faith in the resurrection. We’ll see them all again.