NEVER IN THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD had so many people been united by the promise of free Dilly Bars. As the crowd outside the Dairy Queen in Coppell that January afternoon snaked from the front door, through the parking lot, and down a side street, the fans who had gathered to see Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban serve up treats and eats began to grow restless. After almost an hour, the line had barely moved an inch, but the sudden sight of two men wearing Mavericks shirts brought hope. They were carrying a box full of ice-cream bars. “Cuban’s a little slow on the cash register,” said one of the men as he passed them out. “I thought he’d be used to counting money by now.”

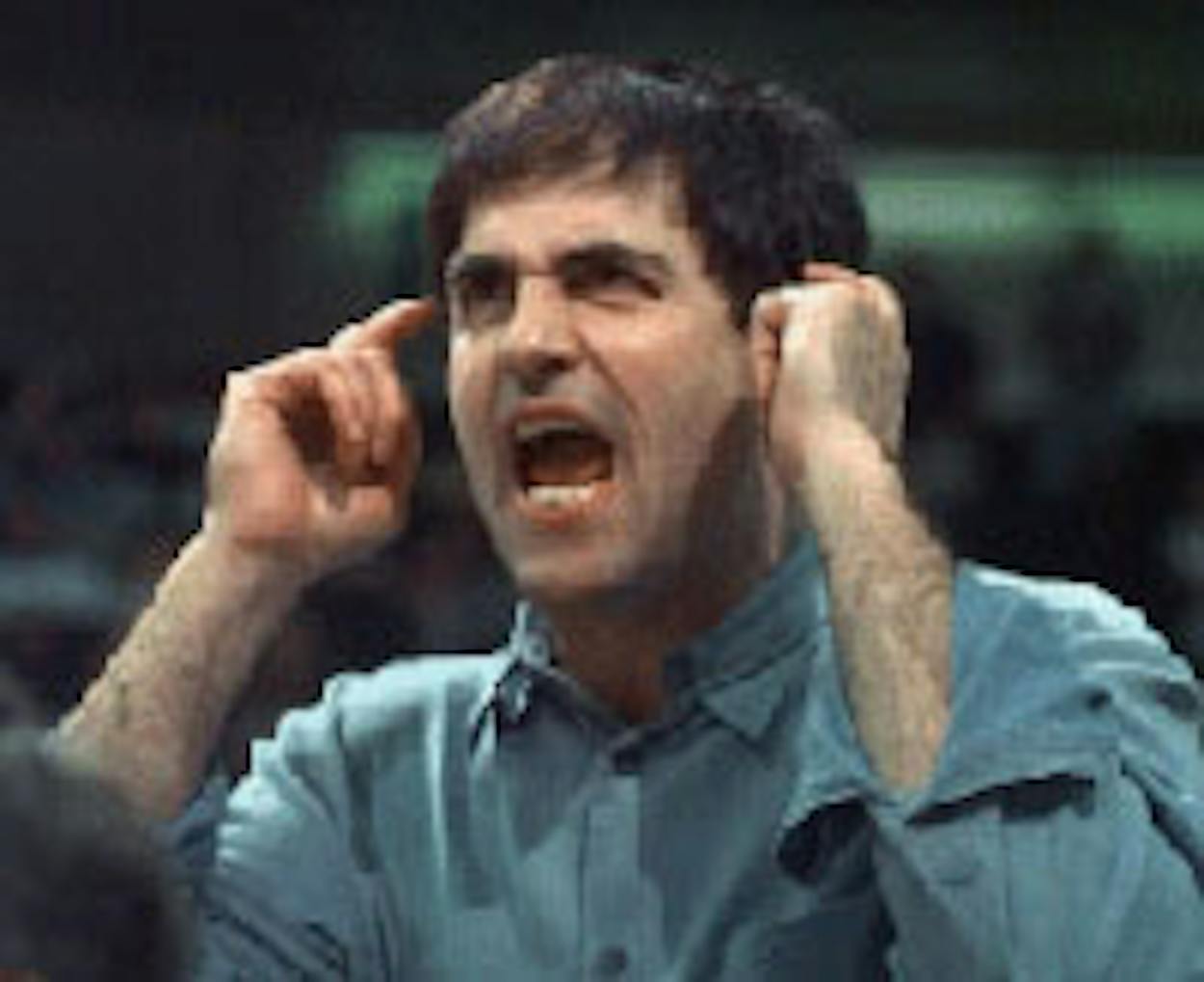

A week and a half earlier the 43-year-old Cuban had criticized a call by an official after a loss to the San Antonio Spurs. Then, in a remark that got almost as much play in the press as the war in Afghanistan, he launched a broadside against the director of officials for the National Basketball Association, saying, “I wouldn’t hire him to manage a Dairy Queen.” That comment earned Cuban the largest individual fine in league history, $500,000. Dairy Queen, however, wasn’t content just to sit in the cross fire. The fast-food chain invited Cuban to run one of its restaurants for a day, he accepted, and one of the grandest publicity stunts in recent memory was born. For the occasion, giant inflatable playscapes were set up in an empty field next door. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones blared from loudspeakers. News helicopters circled overhead. Men and women showed up wearing referees’ jerseys. More than a thousand people came to see the billionaire, and no one left disappointed. Behind the counter, Cuban hopped maniacally about, serving drinks and ice cream and chatting up everyone.

Two things struck me about the performance. First, given all that I had read about Cuban, I expected to dislike him—to discover for myself the petulant, big-mouthed winner of the dot-com lottery. Instead, he was warm, relaxed, considerate, and, well, an awful lot of fun. Second, I had guessed that the people who would bother to show up (aside from probing sportswriters) would display the kind of uniformity one might expect at a Howard Stern book signing: young, white, male, and offensive. I was wrong there too. This turned out to be an all-ages, all-races show. I stood in line with a young family wearing threadbare clothes; next to them were two older women with fur-trimmed coats.

Inside the chaos of the Dairy Queen, Cuban displayed the boundless energy and focus that he has applied to running his team. As he worked on a Blizzard for a young boy, he spilled some on his thumb, then quickly licked it off. “Cuban, we saw that lick,” shouted one fan. “Mark, you’re eating all the profits,” yelled another. Cuban wore his trademark jeans and a royal-blue Dairy Queen shirt, with the right front untucked just so. His manager’s tag said “Tony” because, apparently, Cuban thought that would be funny. He posed for pictures, signed bumper stickers, shook hands, and was as nice as he could be. The ringmaster of the media circus entertained one and all.

Attention on this scale for anything related to the Mavericks would have been unheard of just a few years ago. During the nineties, as the Houston Rockets won back-to-back NBA championships and the Spurs took home their own title, the Mavericks weren’t good enough to be pathetic. From the 1990-1991 season through the 1998-1999 season, the Mavs went 199-507, winning just 28 percent of their games—the worst record of any team in any pro sport during that period. For the pleasure of owning the losing franchise, in January 2000 Cuban ponied up a record sum of $280 million, a small purchase given that he had made $3.8 billion the previous year, when he and his business partner sold their Internet startup, Broadcast.com, to Yahoo!

With his free-spending ways and his taste for confrontation, he quickly made enemies in the buttoned-down world of NBA owners. His shopping spree, for example, didn’t stop with buying the team. Cuban’s well-publicized business plan called for five-star hotels on the road, specially designed chairs on the bench, a flat-screen monitor and DVD player in each locker, and the plushest of towels and robes for every player. Critics claimed that he was trying to buy an NBA title. Cuban countered that he wanted to make his athletes as comfortable as possible—and take away any excuses for losing. Stunts like the hiring of Dennis Rodman (who was fired twelve games later) didn’t help Cuban’s image as an owner looking more for flash than substance. Peter Vecsey of the New York Post called the Mavericks “a freak show” and began referring to the owner as “sleazy Mark Cuban.” Vecsey took particular delight in criticizing the Rodman escapade, writing, “Given the choice between Rodman and Cuban, I’m going with the guy who makes more sense. Rodman claims Cuban’s purchase of the Mavericks was just a publicity stunt.” Last year Cuban and the Mavs were even accused of running up the score. This, as it turns out, was unfair. It was the result of one of Cuban’s more endearing promotions: Whenever the Mavs win at home and score more than one hundred points, every person in the arena receives a free chalupa from Taco Bell.

But what has earned him the harshest criticism are his relentless attacks on the refs and what he considers to be their lack of accountability. In the two years since he bought the Mavericks, Cuban has been fined $1,005,000 for his remarks and other assorted actions (the NBA donates the fines to charity; Cuban, as if to one-up the league, also makes his own matching donations). So what would he do to change the system of grading officials? “Bring in a third party to analyze our process to determine if it is optimal and put in place a system that allows the organization to continuously improve,” he wrote in an e-mail interview. As practical—and as vague—as that sounds, his crusade rolls on, regardless of his critics. “The root problem is that you have people who write about sports and have no understanding of business trying to understand an issue that is entirely a business issue,” he explained. “Most sportswriters don’t fully understand how the salary cap works, let alone what it takes to successfully run a business. As a result, I don’t care what they say or write because it really isn’t relevant to what I’m trying to accomplish.”

It hardly seems as if the NBA’s youngest owner could be accomplishing more or having more fun. He’s a near ubiquitous presence on radio and television. In an interview with Penthouse last year he plumbed the depths of his personal life by telling readers the longest he’s gone without sex since losing his virginity (about eighteen months) and his opinion on whether same-sex couples can raise healthy children (yes, because “good parents are good parents, regardless of their sexual relationship”). He makes his e-mail address available to everyone and answers his messages personally (drop him a line at [email-hidden]. He signs his e-mails “MFFL,” which stands for “Mavs Fan for Life.”

That accessibility would make him little more than an oddity in the world of sports moguls if it weren’t for the fact that his team has been winning. When Cuban took over the Mavericks, just shy of the 1999-2000 season’s midway point, the team responded by going 31-19, a mark that is all the more astounding considering that the franchise was only 9-23 up to that point. The upswing proved to be no fluke. The next season the Mavs went 53-29 and made it to the playoffs for the first time in eleven years, ending what was then the longest drought in the NBA. At the midway point of this season the Mavs had won 29 of their first 41 games—the most in team history—and by the end of January they were in first place in the Midwest Division. Critics can question Cuban’s methods or his personality or even his wardrobe, but they can’t question the results: His hands-on leadership has made the Mavs one of the most exciting teams in the NBA, and he has done it with the same coach and the same core group of players he inherited from the sale.

Indeed, if the Mavericks were distracted by Cuban’s record-setting fine and subsequent fast-food antics, they never showed it. In their first home game after the DQ affair, the Mavs jumped out to a 32-16 lead against the Utah Jazz. Though the Jazz closed the gap late, the Mavs won by playing hard and smart in the final minutes. Even better, everyone went home with a coupon for a free chalupa. “He’s no distraction whatsoever,” says forward Dirk Nowitzki, who is rapidly becoming a league superstar. “He’s his own person, and he can do what he wants. We just focus on the game.” Forward Eduardo Najera agrees: “At first we were all laughing at it, but at the same time, we were impressed. He looked very good, and he really helps the team’s image. When else are you going to see a guy like him do something like that?”

After the win, the crowd standing near the floor of the American Airlines Center wanted to see only one person. Cuban, wearing jeans and an orange sweatshirt, stood at the center of attention. He dresses like a fan, yells at the refs like a fan, and cheers like a fan, so naturally the fans love him. He has no reason to change what he’s doing, and his supporters wouldn’t want it any other way (though he did joke that at one game he “might go shirtless”). He signed anything anyone offered him and instantly put his arm around a woman for a snapshot. As Cuban headed out, a young man wearing nothing but sneakers, Mavericks basketball shorts, and blue body paint caught up with him. They talked briefly, then the man handed him a cell phone. He had set up his voice mail so that Cuban could record the greeting. “Hi, this is Tony, the manager of Dairy Queen,” Cuban said without missing a beat. “Scott’s not here right now, but if you’ll leave your name and number, he’ll call you back.” The fan patted him on the back and skipped off.

It was just another night at the office for Cuban, who, with more grand plans left to hatch, no doubt, sped off in into the Dallas night in his jet-black Lexus SC 430. His license plate, of course, is MFFL.