This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There’s a new CBS TV series called Dallas that is a pulpy chronicle of the boardroom-to-bedroom wheelings and dealings of a Texas oil baron named Jock Ewing. Though Jock and his family are soap opera characters, there is one detail that is absolutely authentic: the rambling antebellum-style mansion where the pilot for the show was filmed really does belong to a Dallas oilman. His name is Cloyce Box. He is a former pro football player, a self-made millionaire, and president of a Dallas-based publicly owned refining company called OKC Corporation.

Like the TV oilman, Box moves in a world of politics and power, of wealth and intrigue. His associates are the kind of people who hand out $100,000 checks as thank-you notes. He maintains an apartment on New York’s silk-stocking upper East Side, and he thinks nothing of climbing into one of OKC’s corporate jets to fly to the races. A licensed pilot, he may even handle the controls himself. He is a friend of governors, a circumstance that has enabled him to serve on the boards of the Texas Department of Corrections and West Texas State University, but it also brought him unwanted notoriety a few years ago when he was involved in a controversial $10,000 cash contribution to Dolph Briscoe’s 1974 campaign. In short, Cloyce Box is the prototype of the successful Texas oilman—except for one thing: he has a unique way of doing business.

Suppose, for example, you owned a refinery, and someone approached you wanting to buy gasoline for 35 cents a gallon. If it was a good price, you would make the sale on the spot. But let’s say that instead you told the customer, “It so happens my brother is a gasoline broker and I prefer to handle my sales through him.” So the customer would buy his gasoline for 35 cents from your brother. You’d refine it, arrange the sale, and ship it to the customer, but you’d “sell” it to your brother for 30 cents a gallon. That would be a little strange, wouldn’t it?

In simplified form, that is how OKC Corporation does business, and Cloyce Box doesn’t think it is strange at all. A lot of people disagree with him—some former directors of the company, who have set off a fierce internal power struggle at OKC; a blue-chip Dallas law firm that the disgruntled directors brought in to perform an in-depth, in-house investigation of the company; and the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which are investigating OKC for possible violations of federal law. Cloyce Box says his business practices are normal and understandable; it’s the circumstances—the recent history of his company and of the oil business, and the federal government’s complex regulatory requirements—that are strange. He may be right; either way, his story shows that the oil industry today doesn’t bear much relation to simple economics.

For nearly five years, OKC has sold about two-thirds of its production through Cloyce’s twin brother Boyce and five close friends. These six have become known as OKC’s “friendly brokers,” and Cloyce’s adversaries insist that these brokers have done little or nothing to earn their substantial profits. If the anti-Box faction is right, the company treasury—and OKC’s shareholders—may have been deprived of millions of dollars. Cloyce is equally adamant in his insistence that the cozy marketing arrangement was the best possible business choice for OKC, and he has some hefty annual profits to back up his claim. But the allegations carried sufficient weight to persuade the firm’s board of directors to name a special investigative committee to look into OKC’s dealings. The committee in turn hired Dallas law firm Locke, Purnell, Boren, Laney & Neely as special counsel, and the lawyers produced a three-volume report that offers a rare and fascinating glimpse into a world where right and wrong have never been easily distinguished: the marketing of oil.

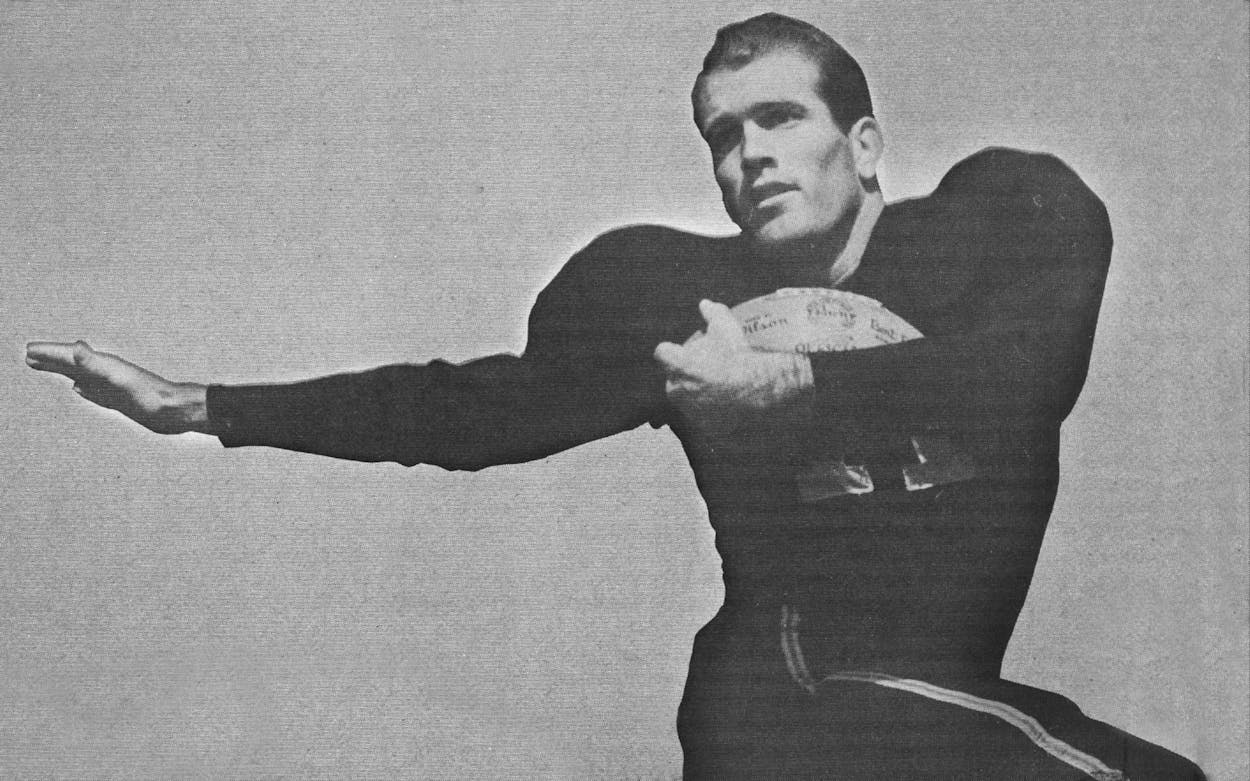

Like Oscar Wyatt of Coastal States Gas, himself a former OKC director, Cloyce Box is one of those overpowering personalities who seem to populate the petroleum industry. Box was in Gatesville, graduated from West Texas State, served in the Marine Corps, and played end for five seasons with the Detroit Lions. After football he became a design engineer for a New York construction company. While there he found out about an inoperative cement plant in Pryor, Oklahoma, which he decided to buy and redesign. With the help of Wyatt and the late K. S. “Boots” Adams, then president of Phillips Petroleum and Cloyce’s mentor, he was able, in 1959, to start the Oklahoma Cement Company.

By the mid-sixties, thanks in part to the building of the interstate highway system, the cement company was booming and Cloyce began to cast his eye elsewhere in the business world. He discovered that a quirk in the federal crude oil import regulations would allow his company to make more money operating an old Phillips refinery in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, than Phillips itself could. In 1966 he arranged for Oklahoma Cement to buy the refinery, and in 1967 the company metamorphosed into OKC Corporation. Boots Adams was Cloyce’s guardian angel in those early years at OKC. The old man arranged the loans that kept OKC afloat, and, more important, he arranged for Phillips to supply all the refinery’s crude and also buy half its output. As a token of loyalty and perhaps to symbolize their common regard for fortitude, Cloyce for years kept in his office a framed photograph of Boots’ intestines, sent to him after Adams underwent abdominal surgery.

Boots Adams, like fellow oil giant H. L. Hunt, sired two families. The first includes rancher-oilman K. S. “Bud” Adams, who owns the Houston Oilers; the second includes Gary Adams, who was to become an executive and a director at OKC and, after Boots’ death in 1975, Cloyce’s mortal enemy. By the early seventies, Boots Adams had relinquished command of Phillips, and the big company began putting a hammerlock on its junior associate by raising its pipeline fees and the cost of its crude. The situation became irreconcilable in 1971 when OKC sued Phillips. As part of the settlement, the supply and sales contracts were terminated, and Cloyce was left, at a lean time for refineries dependent on the import quota system, to find new supplies of crude and new markets for its products. Production at the refinery slumped badly in early 1973, and Cloyce vowed that in the future he would only do business with people he could trust, people who were loyal to him. He would never again let OKC become dependent on big oil.

Just about the time OKC and Phillips parted ways, the oil industry entered a period of unprecedented turmoil: OPEC, a fourfold increase in the world price of oil, the Arab embargo, the wild disruption of supply channels. To cope with the supply crisis, the Nixon Administration issued an almost impenetrable set of regulations that, to simplify them greatly, required refineries to continue selling their products to the same customers they were serving in 1972 at the same prices they were charging in 1973. The regulations caught OKC in a peculiar position, because 1972 was the first year after the OKC-Phillips divorce. OKC had to scramble for crude and sell to customers that were, in the view of management, less than desirable for the long term: rival refineries in some cases, poor credit risks in others. Under the new government policy, OKC was in danger of being saddled with those customers for the foreseeable future.

You didn’t have to be an energy expert to know that 1974 was going to be a bonanza for the oil industry. In Box’s view, something had to be done to secure a trustworthy market for OKC—and something was. Under the right circumstances, the regulations allowed refineries to add new customers: if, for example, a refinery had increased its production since 1972, or if there was a new demand for its products—particularly from farmers and ranchers, since the government gave preference to the use of gasoline in agriculture. OKC had no difficulty qualifying on the first count: 1973 had been its worst year for volume. And soon it qualified on the second.

In the early months of 1974 OKC added five new corporate customers who turned out to have several things in common. All were brokers who, according to applications they filed with the federal government, would be reselling gasoline and diesel fuel to agricultural customers. Yet all five were new to the business of brokering gasoline and diesel fuel. And all were headed by people with close relationships to Cloyce Box, OKC’s board chairman, president, and chief executive officer. In addition to his twin brother Boyce, two of the brokers were Cloyce’s business partners in other ventures, and two others were former OKC officers. Later a firm headed by Cloyce’s personal secretary and her brother would complete the list of new customers who became known as the friendly brokers.

The new brokers were, in Box’s words, “people we selected very carefully, a created organization.” On that point Box and his critics inside OKC agree. But everything else—why they were created, what services they performed for OKC, whether they benefited the company at all—is hotly disputed. Even federal investigators are having difficulty evaluating the role of the friendly brokers, for a conclusive answer requires not only intimate knowledge of energy regulations and federal criminal statutes but also an understanding of refining industry practice and OKC’s unique situation after the Phillips settlement.

In any event, it was not long before OKC and the friendly brokers were involved in some unusual deals that appear not to have been advantageous for OKC but were definitely advantageous for the friendly brokers. In November 1975, for example, National Petroleum Sales sent OKC a purchase order for 22,000 barrels of asphalt at $9.58 a barrel. Former OKC sales manager David Ownby, a 28-year-old Rice University graduate who is a central figure in the story, says Box originally approved the deal but later told him to cancel the contract and reroute the transaction through J. R. Adams (no relation to the Boots Adams clan), a friendly broker and Cloyce’s partner in quarter horse and feedlot investments. OKC sold the asphalt to Adams at $8.50 a barrel. Then Adams sold it to National Petroleum at the original $9.58 price. Loss in revenue to OKC: $1.08 a barrel.

The deal, Ownby later told investigators, was not just an isolated incident, but part of a larger pattern. Time after time, sales orders came directly to the company but were routed, Ownby contends, through a friendly broker at the direction of Cloyce Box, with OKC ending up with less money than if it had dealt directly. In a gasoline transaction similar to the asphalt deal with National Petroleum Sales, a Farmland Industries subsidiary called OKC directly to purchase gasoline for 36.5 cents per gallon; instead OKC sold to a friendly broker for a penny less and let the broker make the sale. This sale cost OKC $84,000.

There is nothing improper, of course, about selling through brokers. Real brokers eliminate the refiner’s need for a costly sales force by developing their own customers. They were particularly important in those hectic days of 1974, when the country was screaming for gasoline, and brokers knew who had it to sell and who wanted to buy. Some brokers simply take commissions for putting buyers and sellers in contact with each other; others operate speculatively, buying and reselling gasoline and fuel oil just as other commodities brokers buy and resell pork bellies and soybeans. They take the risks of market fluctuation. But in 1974, thanks to FEA (Federal Energy Administration, DOE’s predecessor) regulations, there was little risk, since refinery prices were tightly controlled and brokers could resell for much more. Scores of farsighted operators left the big oil companies in 1974 to open brokerage firms; they made quick fortunes and became known as “FEA millionaires.”

Cloyce Box’s friendly brokers made fortunes, all right, but they appear to have operated somewhat differently. They collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in profits on deals that, Box’s critics say, originated with and were arranged by OKC. None had any supplier other than OKC. None had the facilities to store or transport large volumes of fuel. None was required to place himself at the mercy of the marketplace. Their chief assets in the brokering business were an in-box, a telephone, and a close relationship with Cloyce Box. As Ownby tells it, Cloyce didn’t even offer a pretense that the friendly brokers were doing anything for OKC. When an order came in, Ownby would take it to Cloyce, whose normal response was, “Which one are we going to pick this time?” It was, Ownby says, like throwing darts. Then Ownby would call the broker and tell him who to contact and how much the order was for. Cloyce would determine OKC’s selling price to the broker and OKC would actually deliver the product to the customer, since the sale to the broker took place only on paper. Occasionally a broker would even ask Ownby to close the deal with the ultimate buyer. “It seemed ludicrous,” Ownby says.

The brokers made huge profits under this system. OKC’s former treasurer estimated to Locke Purnell investigators that one friendly broker made $2.5 million in the last eight months of 1974 alone. OKC didn’t do badly, either: it chalked up some of the largest profit margins on refinery sales in the history of the company: 19 per cent in 1974, 12 per cent in 1975, and 9 per cent in 1976 (compared to an average of less than 2 per cent during the period from 1970 to 1972, when OKC was feeling the effects of its troubles with Phillips). But Dan Thompson, a former OKC treasurer who now holds a similar position with a national beverage firm, estimates that, without the friendly brokers’ commissions, earnings per share could have been 80 cents higher. Since OKC stock generally sold for around eight times earnings, the friendly brokers could have cost shareholders a total of $6.4 million. That’s the kind of thing that draws the attention of the SEC.

Some of the most controversial deals with the friendly brokers took place near the ends of OKC’s fiscal years in order to adjust the company’s annual profit-and-loss statements. In 1974, for instance, OKC boosted its year-end sales by “selling” large volumes of gasoline to two of the brokers without either delivering it or receiving any money for it until the following summer. That same year, OKC “bought” 289,000 barrels of petroleum products from a friendly broker four days before it was time to close the books, and eighteen days later “sold” it back at the same price. Such transactions are common in the oil industry and are designed to adjust inventories for accounting purposes. They’re legitimate as long as the commodities exist and title to them actually changes hands, even if the product never leaves the seller’s storage tanks, just as grain sitting in a warehouse in Iowa can pass through the hands of a dozen owners without ever moving. But each of those dozen owners, unlike OKC’s friendly brokers, exposes himself to the vagaries of the marketplace. As the company’s former treasurer told Locke Purnell, “Our buy-and-sell transactions were with brokers who had no inventory and no product to actually transfer. They were paper-type transactions.”

The deal that shows most clearly the intimate relationship between OKC and the friendly brokers is a 1974 year-end transaction involving J. R. Adams. In one respect the deal is atypical, because Adams actually paid OKC for the gasoline before he resold it, just as ordinary speculative brokers do. But on closer examination Adams, even in this case, took no risk at all.

In order to pay for the purchase, Adams borrowed $2 million from the Fourth National Bank of Tulsa, where Cloyce Box is a director. Box urged the bank’s president to make the loan, and to secure it OKC bought $2 million in certificates of deposit and promised to repurchase any gasoline Adams couldn’t resell. Obviously OKC, not Adams, was on the line. So when the note was coming due in June 1975 and Adams still hadn’t found a buyer for the gasoline, Cloyce Box arranged for the loan to be refinanced through Mercantile National Bank in Dallas, whose president, Gene Bishop, sat on the OKC board of directors. Again OKC put up security and pledged to buy back the gasoline if necessary.

The list of OKC’s strange business practices could go on and on. For example, Cloyce Box’s secretary continued to draw full pay from OKC while she was in partnership with her brother as a friendly broker during 1974; she also received $100,000 from another friendly broker for helping him to conceive the idea to go into business. But the real question is, what do they all mean? Were they, as Cloyce Box contended to Locke Purnell investigators, sound sales decisions by management? Were they, as David Ownby characterized them to Locke Purnell, “gross mismanagement” not in the best interests of OKC? Or were they, as federal investigators are wondering, indicative of fraud and conspiracy in OKC’s refining division?

The Locke Purnell report supplies a possible rationale behind the arrangement with one of the friendly brokers. The Federal Trade Commission had forced OKC to divest itself of a cement plant in Louisiana, and in December 1973 the company sold it to Don Baxter, who was an officer-director of OKC until the sale. “There are some indications,’’ the report says, “that one of the reasons for permitting Mr. Baxter to broker OKC products may have been to assist him in paying off the note to OKC.” But there are no indications of similar motives behind the other friendly brokers. The Locke Purnell report does refer to unspecified and unsubstantiated allegations by the anti-Box faction that the only logical reason for the friendly broker setup was that Cloyce was receiving kickbacks on the side. But neither Locke Purnell (which examined Cloyce’s income tax returns) nor federal investigators (who are concentrating their attention on Cloyce’s outside business ventures with the friendly brokers) have proved this vital missing link.

Although the Department of Energy has recently elevated its probe of OKC from a routine audit to a high priority investigation, it takes more than unusual business behavior to build a criminal case. The crucial element in proving white-collar crime is intent—whether the friendly brokers were created with a legitimate business purpose in mind or to evade government regulations. Without some proof of sub-rosa benefits to Box, the distinction is one that is easily blurred. It will not be enough for the government to show that the brokers struck it rich in 1974: all oil brokers struck it rich in 1974. As J. R. Adams told Locke Purnell, “I would not be in this brokering business today were it not for FEA regulations.”

The DOE and the SEC are taking two different tacks in investigating OKC. The DOE is focusing on whether the friendly brokers defeated the government’s regulatory system by possibly making false statements to get approved as OKC customers or by jacking up the cost of refined products without performing any services; the SEC’s interest lies in protecting OKC shareholders, who, as we have seen, may have suffered huge paper losses as a result of Cloyce Box’s management policies. The trouble with this theory is that no one suffered a larger paper loss than Cloyce himself, OKC’s biggest individual shareholder with around 400,000 shares. Using the former treasurer’s estimate of 80 cents a share, that means the brokers have cost Cloyce $320,000 in stock value—an unlikely motivation for conspiracy.

Even as the federal agencies pursue their investigations, Box is fighting back with a vengeance. He has retained fiery Austin attorney Arthur Mitchell, whose list of recent clients includes defrocked judge O. P. Carrillo and South Texas mystery man Clinton Manges, as OKC’s general counsel and hired former Dallas Times Herald investigative reporter Hugh Aynesworth (“The Man Who Saw Too Much,” TM, March 1976) for advice on dealing with the media. On a cool Sunday morning in Austin on a UT football weekend, Box, Mitchell, and Aynesworth sat in a university-area coffee shop and defended OKC’s use of the friendly brokers.

“This whole thing is really just an internal dispute in the company,” Box said. “The Adams kids want the company for themselves, as a base for their own operations. They promised Ownby a job if they took over. They’re all in their twenties, and they’ve never even run a service station. Their strategy—and there’s no secret about it; they told me what they were going to do—was to force an investigation and take the results to the board of directors. If they didn’t win there, they’d take it to the FEA. If they didn’t win there, they’d take it to the SEC. If they didn’t win there, they’d take it to Texas Monthly. This investigation never should have happened. The regulatory process is being subverted to help one faction against another.”

As he reviewed OKC’s business practices, the white-haired, bespectacled pro football veteran checked his watch periodically to be certain that business didn’t intrude into the scheduled telecast of a Dallas Cowboys game. He outlined OKC’s rationale for using the friendly brokers: The refinery was producing much more than it had in 1972 and OKC could either sell the excess directly to major oil company refineries, wait for the FEA to assign customers to OKC, or choose new customers itself. After the Phillips experience, Cloyce wanted a buffer between OKC and the majors. At a time when the industry was in a state of upheaval, it made good sense to deal with friends who would pay their bills and wouldn’t complain if a shipment was a few days late. Furthermore, since refiners’ profits were controlled, at least for much of 1974, OKC couldn’t have made any more money by eliminating the brokers.

(It is virtually impossible, without an audit of OKC’s books and a day-to-day understanding of market and regulatory conditions in 1974, to assess Cloyce’s contention that OKC was able to use the brokers and still extract the maximum profit the regulations would allow. But another part of his case for using the brokers doesn’t appear to stand much scrutiny. OKC’s credit manager told Locke Purnell he considered payment within ten days of delivery to be desirable, twenty to be marginally acceptable. From 1974 through 1976 no friendly broker averaged better than a sixteen-day delay in paying. Boyce Box averaged 69 days, which since 1974 has cost OKC almost $60,000 in lost interest.)

There are two other points that are basic to Cloyce’s defense of the friendly brokers. One is the proof-in-the-pudding argument: OKC’s solid profits on refined sales while using the friendly brokers. The second goes back to the way federal regulations worked: once the friendly brokers were approved as customers, says Cloyce, OKC had to sell them a certain amount of fuel every month. The problem with this argument is that the regulations only bind a company like OKC if its customers ask for their quota every month; in the case of the friendly brokers, it was OKC who called them every month to offer supplies.

What makes the OKC case so important, and so fascinating, is that it raises some very basic questions about the oil business and federal regulation. Suppose, for a moment, that Cloyce Box figured out, as others in the oil business figured out, that fortunes could be made in the brokerage business by purchasing gasoline at frozen refinery prices and reselling it, as permitted, for more. What is the difference between going into that business yourself and helping others do the same thing? Why should one be described as exploiting a loophole, the other as committing a crime? Suppose, too, that Cloyce did get some remuneration from the friendly brokers? Does this prove a conspiracy? Or does it simply reflect the world Cloyce Box moves in, a high-rolling world where you tip someone off to big money today and next month he does the same for you?

Of course, if consumers or OKC’s shareholders suffered because the company dealt through the friendly brokers, that’s a different story. But if the case against Box rests on the charge that he undermined a government regulatory scheme of dubious merit, that is not likely to make much of an impression on a jury in a state that has grown fat on oil.

Meanwhile, the show goes on. After the Locke Purnell investigation, the OKC board backed Box in a showdown vote and Gary Adams resigned his positions as officer and director. Ownby too has departed. The eleven directors remain split, but Box retains a 7–4 edge. OKC still does business with the friendly brokers and the brokers have still been slow in paying their bills. Federal investigators are still determined to haul Cloyce Box into court. Only one thing has changed: this fall, CBS began filming Dallas in a different house.

Andrew Sansom is a freelance writer living in Lake Jackson.

- More About:

- Energy

- TM Classics

- SEC

- Dallas