Four hours before Miranda Lambert is scheduled to perform in front of five thousand fans in Corbin, Kentucky, she’s making a beeline for the commissary that has just been set up by her road crew. “I’m sorry, but if I don’t start eating right now, I’m literally going to die of starvation,” she says to no one in particular as she fills up a plate of food. She sits down at a table, spears an entire chicken breast with her fork, lifts it toward her mouth, and then notices me sitting across the table, notebook in hand, ready to write down what will happen next. For several seconds the chicken breast hangs in the air, quivering on her fork. Miranda tosses back her magnificent mane of blond hair and stares at me with one eyebrow raised. She shifts in her seat, sliding one leg underneath the other.

More seconds pass.

“Well, crap, there goes my ladylike image,” she finally says as she leans forward and rips into the chicken. After a few seconds of high-speed chewing, she takes another equally giant bite.

“Pretty impressive,” I murmur.

“Thank you,” she replies. “People think you can only enjoy food if you eat it slowly. Well, I’m here to tell you that it tastes just as good when you eat fast. And I like eating fast. I’ve got things to do.”

Since arriving in Corbin earlier this July day, Miranda has run laps in the parking lot of the local arena, with her ragtag parade of small dogs—Cher, Delta, and Delilah—trotting diligently behind her. She has performed a series of lunges next to her tour bus, and inside, she has whipped through a few dozen push-ups and sit-ups. She’s met with her manager to talk about her new album, Four the Record, which will be released in November, and she’s talked to her publicist about her newest venture, an all-female band called the Pistol Annies, which she formed last year with two of her friends and whose self-titled debut album is coming out in less than a month. And as soon as she finishes eating, she’s scheduled to meet with some New York advertising executives who have come to Kentucky to try to persuade her to become the national spokesperson for one of their products.

The dinner is over in less than five minutes. Miranda stands up and brushes a few crumbs off her tank top and low-slung blue jeans. “Holy crap!” she says, giving me a dazzling smile, the dimples in her cheeks so deep they could hold water. “I’ve got to get moving.”

For nearly a decade, she has been a blur of activity. It wasn’t long ago that she was just another small-town Texas teenager who dreamed of becoming a country music star. She lived in Lindale, outside Tyler, and she was so determined to get her career started that she entered a program in high school called Operation Graduation—“made up of a bunch of pregnant girls and druggies and me,” she recalls—so she could finish early.

There was no question she could belt out a song: in 2003, at the age of nineteen, she placed third on Nashville Star, a country music talent show that aired on the USA cable network. But it was hard to imagine her becoming one of country music’s next big things. In no time, the leggy, high-heeled Carrie Underwood would win American Idol, singing glossy pop-country songs that had been crafted to appeal to a mainstream audience. Her first hit, “Inside Your Heaven,” was about a woman hopelessly in love with a man. “You’re all I’ve got,” Carrie sang. “You lift me up. . . . All my dreams are in your eyes.”

Miranda insisted on doing songs she had written or co-written, and her lyrics were about as mushy as a Cormac McCarthy novel. One of her songs celebrated a vindictive woman who had decided to burn down the house of her cheating lover. Another told the story of a lady sitting by the door with a gun, waiting for her abusive man to come home from jail. Miranda wrote about girls who cussed, drank too much, packed pistols, and raised hell. Her gals didn’t have time to pine over their two-timing men. They were too busy plotting to get even.

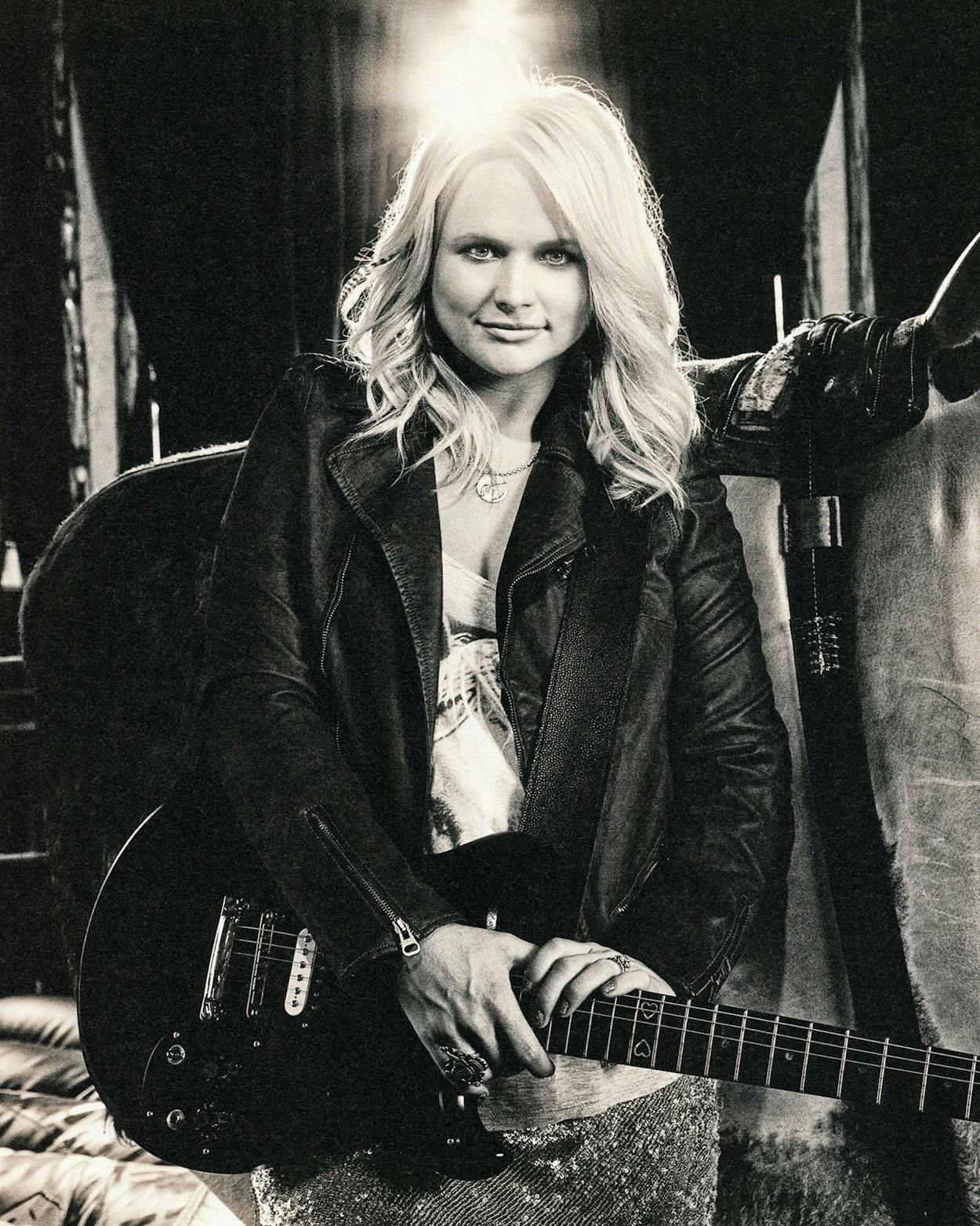

Nashville insiders were mystified by this pillow-lipped little teenager, just five feet four inches tall. “Light ’em up and watch them burn,” Miranda would sing about no-good dudes in her country twang. “Teach them what they need to learn . . . I’m givin’ up on love, ’cause love’s given up on me.” Only one word could describe her consonant-dropping, take-no-prisoners style: “twangry.”

Today those Nashville insiders are falling all over themselves to have their photos taken with her. In the words of Rolling Stone magazine critic Will Hermes, Miranda, who’s now 27, is “the most gifted woman to hit country’s mainstream in a decade.” The three albums she has released since 2005 (Kerosene, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, and Revolution) have all gone platinum, selling at least a million copies each. Three of her singles from Revolution alone went to number one on the Billboard country music charts. And in the past year, she has won a Grammy, three Country Music Association Awards (in addition to being named female vocalist of the year), and four Academy of Country Music Awards.

What’s most remarkable is that Miranda has achieved such commercial success without sacrificing what Jon Caramanica, the country music writer for the New York Times, describes as her “sharp tongue, a penchant for flamboyant lyrical gesture, and a cooing voice that only barely sugarcoats deeply acidic thoughts.” Indeed, Miranda is still relentlessly knocking out one song after another about rowdy women who, when wronged, don’t think for a second about standing by their men. The first single released from Four the Record, “Baggage Claim,” is about a girl who trashes her wayward beau’s worldly goods.

Also on the album is a duet that she recorded with her new husband, Blake Shelton, the popular good-old-boy country singer from Oklahoma and celebrity judge on NBC’s The Voice. And what, in her newly married bliss, did she choose for her and Blake to record? A song called “Better in the Long Run,” about a couple who’s breaking up.

“What can I tell you? It’s a heck of a good song,” Miranda says. “And let’s face it, isn’t the dark side a lot more interesting? Seriously, if all I did was sing about all the really nice things that happen to women, I’d be bored to death.”

Since country music began, female singers have wailed over the plight of fellow women caught in relationships with no-good men. “Most every heart that’s ever been broken was because there always was a man to blame,” sang Kitty Wells in her 1952 classic “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels,” the first song by a female artist to hit number one on the Billboard country charts. Two decades later, in “I Wanna Be Free,” Loretta Lynn reveled in the possibilities a divorce from a hard-drinking husband might bring (“I’m gonna take this chain from around my finger and throw it just as far as I can sling ’er”), and in 2000’s “Goodbye Earl,” the Dixie Chicks had an abusive husband unabashedly murdered and dumped in a lake by his wife and her best friend. Even Carrie Underwood released the single “Before He Cheats,” about a woman taking revenge on an unfaithful boyfriend by keying his truck and smashing the headlights with a baseball bat (of course, in her music video, Underwood carries out the vandalism while wearing high heels).

But no one has sung these kinds of songs as often and with such relish as Miranda Lambert. She is part blond babe and part saucy shitkicker, the kind of gal who’s pretty enough to win a beauty contest but tough enough to crack open someone’s head with a beer bottle. “Look right here,” she tells me, pointing to an elaborate tattoo spread across her left arm of two intertwined revolvers graced by angel wings. “That defines who I am. The wings are my way of saying, ‘I’m a nice, down-home, small-town girl.’ ” Then she points to the pistols, and for a moment her eyes narrow. “But if you do me wrong, you better watch out, because I won’t take any of your crap.”

That philosophy, as simple as it is, has become a call to arms for a loyal, growing fan base, made up mostly of women under the age of forty. When Miranda heads off to her post-dinner meeting, I walk out to the parking lot, where a few dozen fervent “Ran Fans” are already gathered behind a security fence, holding cameras, desperate to get a shot of their heroine. One young woman, who’s wearing a straw cowboy hat, a flowered dress with spaghetti straps, and cowboy boots, tells me how the hit song “Gunpowder and Lead”—a seething tune about a woman lashing out at a punishing ex-boyfriend that Miranda dreamed up while taking a concealed-handgun class—changed her life. “That song helped give me the courage to break up with my own boyfriend, who treated me like dog meat,” exults the young woman.

When I remark that “Gunpowder and Lead” seems to suggest that firearms, not diamonds, should be a girl’s best friend—“He’ll find out when I pull the trigger!” is one of the more memorable lines—another Ran Fan, in a midriff-baring shirt, Daisy Dukes, and boots, jubilantly shouts, “Hell, yeah!”

I then bring up “Kerosene,” the song that first made Miranda famous—yes, the one about a girl wanting to burn down the two-timing boyfriend’s house—and more Ran Fans chime in with such comments as “You know that every girl fantasizes about doing something like that.” I ask if any of them have ever gotten out of control like the girl in another Miranda single, “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend,” who threatens to beat up an old boyfriend’s new girlfriend in a pool hall, and they all just look at me as though I’m one more clueless man. “Miranda puts into words what we’re all thinking,” someone says from the back of the crowd, which sets off a group cheer.

“Women love her badass attitude,” says Miranda’s mother, Bev, who helps handle Miranda’s merchandising from her home in Lindale. “Last year we started selling a camouflage hoodie with a line from one of her songs printed on the back that read ‘Time to Get a Gun.’ And it sold like crazy. Wearing that hoodie was her fans’ way of saying that they were badasses too.”

Miranda’s father, Rick, estimates that her merchandise sales are now “easily ten times higher than they were a year and a half ago.” Rick oversees the Miranda Lambert Store and Red 55 Winery (named after Miranda’s favorite truck, a red ’55 Chevy) in downtown Lindale. That’s right, Miranda now has her own private wine label, with the wine coming from the LouViney Vineyards, in nearby Sulphur Springs. One of the offerings is called Kerosene; another is Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. “They must be like an aphrodisiac to her fans, because they’re buying them by the case,” Rick notes. “For these women, it’s all Miranda, all the time.”

Men, on the other hand, are a little bewildered. In 2008, after listening to “Gunpowder and Lead,” the editors of Esquire named her Terrifying Woman of the Year in their annual music awards issue, concluding, “It’s tough to tell where the insanely violent characters begin and the real Miranda Lambert leaves off.”

“I remember when Miranda first came out with her ‘Kerosene’ video,” chuckles her husband, who called me from his tour bus in Michigan, where he’s promoting his new album, Red River Blue, which hit number one on the Billboard country charts in late July. “You’d see all these guys doing double takes. Here she was, walking down this dirt road, so unbelievably hot-looking in these tight jeans and tight T-shirt and with all her blond hair bouncing around. And she gave the camera this nonstop sexy look with those damn sexy eyes of hers. You could just hear guys saying, ‘Oh, man, who is that?’ But all the while she was walking, she was pouring kerosene leading out of her boyfriend’s house, and at the end of the song, she threw a match. And those guys who were getting so worked up were suddenly saying, ‘Run for your life!’ ”

A man is likely to become only more bewildered when he meets Miranda in person. She not only has the perfect teardrop face but her voice is as buttery as a biscuit. “I’m sorry I say ‘crap’ so much when I talk, but I do like the word,” she tells me during one of our conversations, popping out some lip gloss, as she does every ten minutes or so, and touching up her lips. She is also utterly unpretentious. She will happily spend an hour talking about all the abandoned dogs she and her mom have adopted (Miranda now owns seven but takes only Cher, Delta, and Delilah with her on tour). Or she’ll chat about the books she’s reading (The Help and Hunger Games). Or that she likes to bake chocolate-chip cookies.

“Oh, listen, she’s a complete, one-hundred-percent sweetie,” Blake says.

“Always?” I ask.

“Always,” he replies. There’s a silence, and then he laughs again. “But come on now. Do you think I’m dumb enough to risk getting in any trouble with her? Do you think I’m that stupid?”

For most of the seventies, Miranda’s father was a cop for the Dallas Police Department, assigned to the patrol division, then to undercover narcotics, and then homicide. He also sang in a country band named Contraband, which played at all the country-and-western joints along Greenville Avenue. “It was a good way to meet drug dealers and make undercover buys and get them off the streets,” says Rick, a stocky, good-looking man who loves to tell stories. “And by the way, it was also a good way to meet Dallas stewardesses.” Then he met Bev, a former junior college cheerleader from East Texas who was working in Dallas as a leotard-wearing fitness instructor at an Elaine Powers Figure Salon, a gym for women. “Lights out,” he says. “That girl had it all.”

After Miranda was born, the Lamberts moved to Van Alstyne, north of Dallas, and opened a small detective agency. At one point, when business slumped, they lost everything, moved to Lindale to live with Bev’s brother, and later rented a ramshackle house that was about to be bulldozed. The Lamberts planted a garden, and they raised chickens, pigs, rabbits, and goats. “If I saw a deer in the pasture, I’d run out and try to shoot it, whether it was deer season or not,” says Rick. “We were that flat-out poor.”

In 1997 the Lamberts got back on their feet when they were hired by the lawyers of Paula Jones, a former Arkansas state employee, to look into allegations that she had been sexually harassed by Bill Clinton when he was Arkansas’ governor. Rick finally got his family out of the rent house and moved them into a 4,800-square-foot home in Lindale. A few months later, when the preacher at their church saw how big the house was, he asked the Lamberts if they would mind taking in a woman who was being beaten up by her husband. Soon, another abused woman arrived, with her children. “I told the women that we would clothe them and feed them as long as they told their husbands not to step foot on our property, because if they did I would ask no questions,” Rick says. “I would get out my gun and drop them in the front yard.”

By then, Miranda was fourteen years old. When she’d get home from school, she’d sit in the den and listen to one of the abused women, tears streaming down her face, talk about what she’d endured. Some nights, she’d sleep on the floor in her parents’ bedroom while a woman slept in her bed. Other nights, when it was just the family at the house, she would sit with her little brother at the dinner table and listen to her parents talk about their investigations. “We talked about who was cheating on who or who was shacking up at some motel, and she’d quietly take it all in,” says Rick. “She heard about some gal who had been left dead-broke by her husband, who had walked out on her and the kids. She heard about some other gal who was so down on her luck she started drinking and getting in trouble. And she’d say, ‘Daddy, it isn’t right what those men are doing.’ When I look back on those years, I realize she was getting a clinic in how to write a country song.”

Throughout her childhood, Miranda had sung along with Rick when he had “picking parties” on his front porch for his neighbors and hunting buddies. At the age of sixteen, she competed in a country music talent show in Longview. Although she lost in the second round—she was the only teenager competing—she was hooked. Rick put together a little backup band for her, and he and Bev began driving her to honky-tonks, where she performed a lot of Tanya Tucker and Rusty Weir covers, mostly in front of drunk rednecks. One night, in Dallas, while she sang in a railroad car that had been converted into a bar, a bloody fight broke out involving five or six patrons. Undeterred, Miranda kept singing, not missing a note, not even when everyone in the bar spilled out to the parking lot to keep the fight going.

At another Dallas hole-in-the-wall, some guy asked her if she wanted to smoke pot. She promptly told Rick, who put him in a choke hold. “Miranda started yelling, ‘Kill him, Daddy! Kill him!’ ” says Rick. “She was trying to get ready to sing, and she was pissed that someone was trying to mess her up.”

“No, that isn’t exactly what she said,” sighs Bev. “She only yelled, ‘Kick his ass, Daddy! Kick his ass!’ ”

When she wasn’t touring honky-tonks, Miranda would sit with her guitar on the floor of her bathroom, where the acoustics were good, and, using the five chords her father taught her, knock out one song after another. None of them were about kissing boys or cruising around the town square with her girlfriends. In one song, she described a desperately unhappy woman falling in love with Jack Daniel’s. “He’s the best kind of lover that there is,” wrote Miranda, who was still years away from the legal drinking age. “I can have him when I please, he always satisfies my needs.” In another, she described a woman driving down Highway 65, trying to escape her life. “Wanna feel my freedom blowin’ through my hair,” wrote Miranda, who had only recently gotten her driver’s license. “Throw my troubles to the wind and scream out, I don’t care.”

“One day,” recalls Rick, “she walked into my room while I was strumming some chords on my guitar, and she suddenly sang to the melody I was playing, ‘Rain on the window makes me lonely.’ We both came up with some more lines, and in an hour and a half, we had a song about a woman sitting on a bus, devastated by the end of an affair with a married man. We played it for Bev, and when Miranda sang, ‘I’m gonna find someplace I can ease my mind and try to heal my wounded pride,’ we both shook our heads. Miranda had this eerie ability to take on someone else’s story and make it her own.”

Miranda sang that particular song, “Greyhound Bound for Nowhere,” in the finals of Nashville Star. Later, she met with executives from Sony BMG in Nashville. “We walked into a room filled with about twenty people,” says her agent, Joey Lee, “and they started going through their thing, saying, ‘We need you to write with this person and work with this producer so that we can produce a great record.’ And Miranda basically stopped everyone in their tracks and said, ‘Have y’all listened to my songs? Because that’s who I am and that’s what I’m going to keep doing, and if I can’t do it my way, I’ll go home and come back when you’re ready for me.’ She was eighteen years old and walking away from a major record deal. And right then, to his credit, the president of the label said, ‘Okay, Miranda, go make your record.’ ”

When that first record, Kerosene, was released, in 2005, the programming directors for country music stations were put off by the songs’ straight-talking females. Not one of Miranda’s four singles from the album cracked the top ten of the Billboard country singles chart (which is heavily determined by radio play). But the album itself went to number one on the Billboard country album chart. So did her second album, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. Clearly, as the great country singer Kenny Chesney would later say, Miranda “was singing to an audience that wasn’t being sung to.”

By 2009, when she released Revolution, country radio was waiting for her with open arms. Three singles from that album went to number one: “White Liar,” whose character warns devious dudes that she’ll get the last word if they mess around on her; “Heart Like Mine,” about a frisky female who declares, “I heard Jesus, he drank wine, and I bet we’d get along just fine”; and “The House That Built Me,” a heartbreaking elegy to a young woman making one last visit to her childhood home, still trying to deal with some unnamed loss.

Revolution earned Miranda so many awards she didn’t know where to put them. Yet she never took a break. She went straight back to work writing new songs for Four the Record, and she formed the Pistol Annies. (If you think they aren’t created in Miranda’s image, consider their first single, “Hell on Heels,” about a group of women who swindle righteously from bad men.) Country Music Television’s Chet Flippo, the dean of Nashville critics, is already calling the Pistol Annies’ debut album, which came out in August, “one of the best albums of 2011.”

Meanwhile, she never stopped touring, performing eighty to a hundred concerts a year, many of them in smaller cities like Corbin so that her rural fans—“who could use some cheering up these days,” she says—could get a chance to see her. She was so determined to keep performing that she gave herself only eight days off for her wedding and honeymoon. The celebrity-packed affair was held at a ranch near San Antonio. Miranda and Blake exchanged vows on a cowhide rug beneath an arch decorated with deer antlers, and they walked back up the aisle after the ceremony to the classic Roy Rogers tune “Happy Trails.” At the reception, the guests ate venison from deer that had been shot by the newlyweds.

“The whole thing sounds both gloriously regal and gloriously redneck,” I tell her. She gives me a look, and I realize I have said the wrong thing.

“I don’t think there was anything redneck about it,” she says indignantly. “It was just us.”

The next day, the newlyweds went back to Blake’s Oklahoma ranch, finished opening their presents (among their favorite gifts: matching shotguns and his-and-her flasks), and went fishing. Miranda tweeted a photo of herself during the honeymoon, holding a bass she had caught. Then they flew to Reba McEntire’s vacation home in Cancún, where Blake says he drank the water and got diarrhea.

On their days off from their separate tours—usually Monday through Wednesday—Miranda and Blake fly in private planes to Oklahoma and meet up at Blake’s 1,200-acre ranch near Tishomingo (population 3,293). “We piddle around, go back-roading, build brush fires, shoot at targets with our hunting bows. You know, the usual,” Miranda says. “Sometimes I get him to go to the Walmart with me over in Ada. Or sometimes we go into town and hit the Dairy Queen.”

After dinner, they curl up on the couch and watch true-crime shows on television (when I ask Miranda why she likes true crime, she says, “Dude, really? Have you heard my songs?”). Then, after downing a couple of “Rana-ritas”—a drink she created that’s made up of Crystal Light Raspberry Lemonade, a shot of Bacardi, and a splash of Sprite Zero—they pull out their guitars and start singing. “Whenever we sing together, I try to outsing her and make her sound sucky,” says Blake, “and she does everything she can to make me look bad, and this goes on and on, all night long, like two dogs fighting for a bone.”

Blake, who’s a good six feet five before he puts on his boots, and Miranda are a country music version of Nick and Nora, the always bantering married couple from the classic old film The Thin Man. They can’t go five minutes without getting into some comic exchange about each other’s flaws. Blake calls Miranda “the most damn hardheaded and uncompromising woman on the face of the earth. Once she makes up her mind about something, that’s how it is, no matter how wrong she might be.” Miranda, in turn, calls Blake, who used to wear a mullet, “a big old Oklahoma blowhard.”

Blake and Miranda even keep up their needling through their Twitter accounts. In early July, Blake was booked to sing on NBC’s Today show on exactly the same day and at exactly the same time that Miranda was booked to sing on ABC’s Good Morning America. Blake began tweeting his fans, exhorting them to watch him. Miranda shot back in her own tweet, “They won’t be watching you. They will be watching me!” Later she reminded Blake that she had a secret weapon to get more people to tune in to her show. “I have boobs,” she wrote. Blake replied, “True, but only two.” Miranda quickly wrote, “Well, if you count Pistol Annies, I have six!”

Blake admits that Miranda jumps on him when he has a little too much to drink and starts tweeting things that get him in trouble. “And if I ever tweet something about another girl being hot,” he says, “or if some female fan tweets me saying, ‘Blake, I love you,’ Miranda sees it immediately and she’s on my ass, going, ‘What is that about?’ When Miranda marks her territory, it’s marked, and I love her for that. I love knowing she’s that passionate about me.”

But during my conversation with Miranda, she makes it clear that that love goes only so far beyond the border of Texas. She’s told Blake in no uncertain terms that when she’s pregnant and goes into labor, “I’m jumping in the car and hauling ass to Texas. It takes exactly forty-two minutes to get from the ranch to a hospital I’ve picked out right on the other side of the border, and that’s where I’m going to be. Our child is going to be born a Texan.”

“I told you, she’s her own girl, and she always will be,” says Blake. “But if you ask me, that’s what sets Miranda apart from all the other female country artists who are out there. She’s done it exactly her way, singing the songs that are important to her. Hell, the way her career is going, I’m soon going to be able to retire and hang out on the ranch and hunt deer and drink some beer. I’m telling you, Miranda is awesome!”

Although she still doesn’t sell as many records as the other two female country stars who are under the age of thirty—Underwood and Taylor Swift—there are signs that the rest of America is getting to know Miranda. Us Weekly, the celebrity magazine of record, put her and Blake’s wedding photo on its cover. And the ABC Family Network is developing a TV series based on Lambert’s family: the drama follows two private investigators whose children, one of whom is a budding country singer, assist in solving crimes. “It’s sort of like Nancy Drew meets Hee Haw,” says Rick.

What will really make Miranda take off, of course, is a crossover hit that even non–country music fans want to hear. She came close with “The House That Built Me.” “And I did record a song for the new album that’s the first genuine love song I’ve ever written in my life,” Miranda tells me. “It’s called ‘Safe.’ It’s about a woman feeling safe with a man, and I wrote it in thirty minutes while sitting on Blake’s bus. He was onstage performing, and I was supposed to be watching him, but this idea hit me and I started writing, and boom, I had it.”

“Give me one of your best lines from the song,” I say.

She squinches her eyebrows together. “Well, okay, this doesn’t sound like me, but one line goes, ‘You walk in front of me to make sure I don’t fall and break my own heart.’ ”

“That doesn’t sound like the typical Miranda song. Maybe you’re changing.”

Her eyebrows rise, almost mischievously. “Don’t count on it,” she says. “I still got a lot of attitude left.”

It’s now nine o’clock in Corbin, and Miranda is backstage in her concert attire: a T-shirt made by Haute Hippie, a blue-jean vest, a tiny blue sparkly skirt, and cowboy boots with fringe. She’s wearing a necklace she bought at Junk Gypsy (a funky knickknack shop in College Station), with a pendant reading “You gonna pull them pistols or whistle Dixie?” And she’s got on hoop earrings the size of basketball rims. Her hair is huge—she always does her own hair and makeup before concerts—and, predictably, there’s a tube of lip gloss in her hand.

“Let’s go,” says Miranda, downing a Rana-rita, and at precisely 9:10, she and her band hit the stage. The sound that comes from the audience can only be described as a sort of high-pitched primal scream. Miranda launches into “Only Prettier,” about a woman staring down a snooty woman from the good side of town. “Well, I’ll keep drinkin’ and you’ll keep gettin’ skinnier,” she sings. “Hey, I’m just like you, only prettier.” She then goes straight into “Kerosene,” and at the end of the song, she raises her microphone stand into the air: it’s in the shape of a shotgun (the microphone itself, by the way, is a bright girly-girl pink). “I’m here to tell you, I’m a redneck chick,” Miranda shouts, her outlaw persona in full bloom. “I’m a hell-raising, deer-killing, chicken-fried-steak-eating redneck, and I don’t take crap off of anybody!” The primal scream in the audience becomes a full-throated roar.

The New York Times’ Jon Caramanica describes a Miranda concert as a “theater of rural feminism.” It’s doubtful any of the women in the audience have actually picked up a pistol and aimed it at a man. Miranda herself told me that she’s never gotten so pissed off at a guy that she resorted to violence. “There was one time in high school when I was talking on the phone to my boyfriend, and he said he couldn’t go out with me that night,” she says. “But then he mentioned he was ironing a shirt, so I knew something was up. I drove with my friend to a bar in Tyler where I thought he might be and saw his car in the parking lot. I turned around and went home. Then, the next day, I looked as pretty as I had ever looked going to high school, and a couple days after that it was his high school graduation, and I looked as pretty as I could again. That’s when I broke up with him, right then on graduation night.”

“That’s it?”

“It really wasn’t very nice,” she says. “I mean, his whole family was there.”

Still, Miranda knows that the women in her audience—heck, maybe all women—love the fantasy of letting loose and throwing all the frustration of their lives back into men’s faces. The last song of her ninety-minute concert, “Gunpowder and Lead,” is easily the highlight of the night, with the entire audience bellowing along to lyrics that one would think would be more appropriate for a rap song. Miranda stomps across the stage, whips around in a frenzied circle, claps her hands, tosses her hair back and forth, and lets out a half-crazed whoop on the final chord. Just before the lights come up, she gives her fans her famous beautiful smile and shouts, “I love you!”

I notice, to my surprise, a number of men scattered throughout the audience, staring at her in rapt fascination. Perhaps they are at the concert because their girlfriends have dragged them there. Or perhaps they figure the concert is going to be a perfect place to meet hordes of single women. “Or maybe they were there because they secretly love Miranda,” Blake later suggested. “Why wouldn’t they? She lets you know she’s a real woman. I think, deep down, guys look at Miranda and say, ‘I wish I had somebody like that.’ ”

After the concert, Miranda calls for her dogs and then heads for an Airstream trailer parked next to her tour bus. “My little getaway,” she calls the Airstream, which comes along on all her tours and has been renovated to look like a miniature lounge, complete with several small couches, a television, and a bar. She sips another Rana-rita and chats with friends and band members. For some reason, she starts talking about her favorite fast foods: the ten-piece Chicken McNuggets at McDonald’s, the burger meal at Sonic, the crispy-chicken sandwich from Burger King. “It’s terrible for me, but I love all that damn food,” she says, unpretentious as ever.

Soon she’s off to her tour bus, her three dogs trotting behind her. She’s got to call a couple of girlfriends—she’s planning a girls’ float trip down a Hill Country river for later in the summer—and she wants to call Blake to tell him she loves him and “to let him know that I’m sure I sang better tonight than he did.”

In the distance, a few last Ran Fans are still standing behind the security fence. When they get a glimpse of Miranda, they let out a cheer. Miranda turns and gives them a fist pump, and they cheer again. At least for a moment, all is right in their world.

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Miranda Lambert

- Lindale