Just minutes into the live coverage of the Scripps National Spelling Bee semifinals on Thursday, May 31, 2007, ESPN’s Stuart Scott sets up for a shot near an entrance to the Independence Ballroom of the Grand Hyatt Washington. Scott is one of the marquee anchors of the hugely popular SportsCenter, known for his mashed-up play-calling style and his catchphrase “Booyah!” He can usually be found interrogating star athletes, like LeBron James and Tiger Woods. This morning his subject is a thirteen-year-old with a black mop-top and braces.

“Dan Marino: seventeen years, one of the best quarterbacks ever, never won a championship,” Scott says. “Samir Patel right here: This is his fifth spelling bee. One of the best young spellers we’ve ever seen, but you’ve never won. You’ve finished fourteenth, second, third, twenty-seventh. How are you going today to pull off what Marino never could?”

“Well, you know, there’s so much luck involved in the spelling bee,” Samir responds. The kid is stupefyingly professional. He makes eye contact like a debate team captain and doesn’t seem vexed by any of the awkward eccentricities that usually plague great child spellers. Only the bee uniform—a white polo buttoned all the way to the top and a placard hanging around his neck emblazoned with his number, 247, and his sponsor, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram—supplies the requisite notes of nerdy pageantry that most fans associate with the contest.

“You can’t necessarily really say just that I’m the best speller, because there’s so much luck,” Samir says.

“There’s luck and there’s confidence,” Scott replies. “Some of these students, they get up here and they get a little nervous. Confidence will knock a person over if he’s standing next to you.”

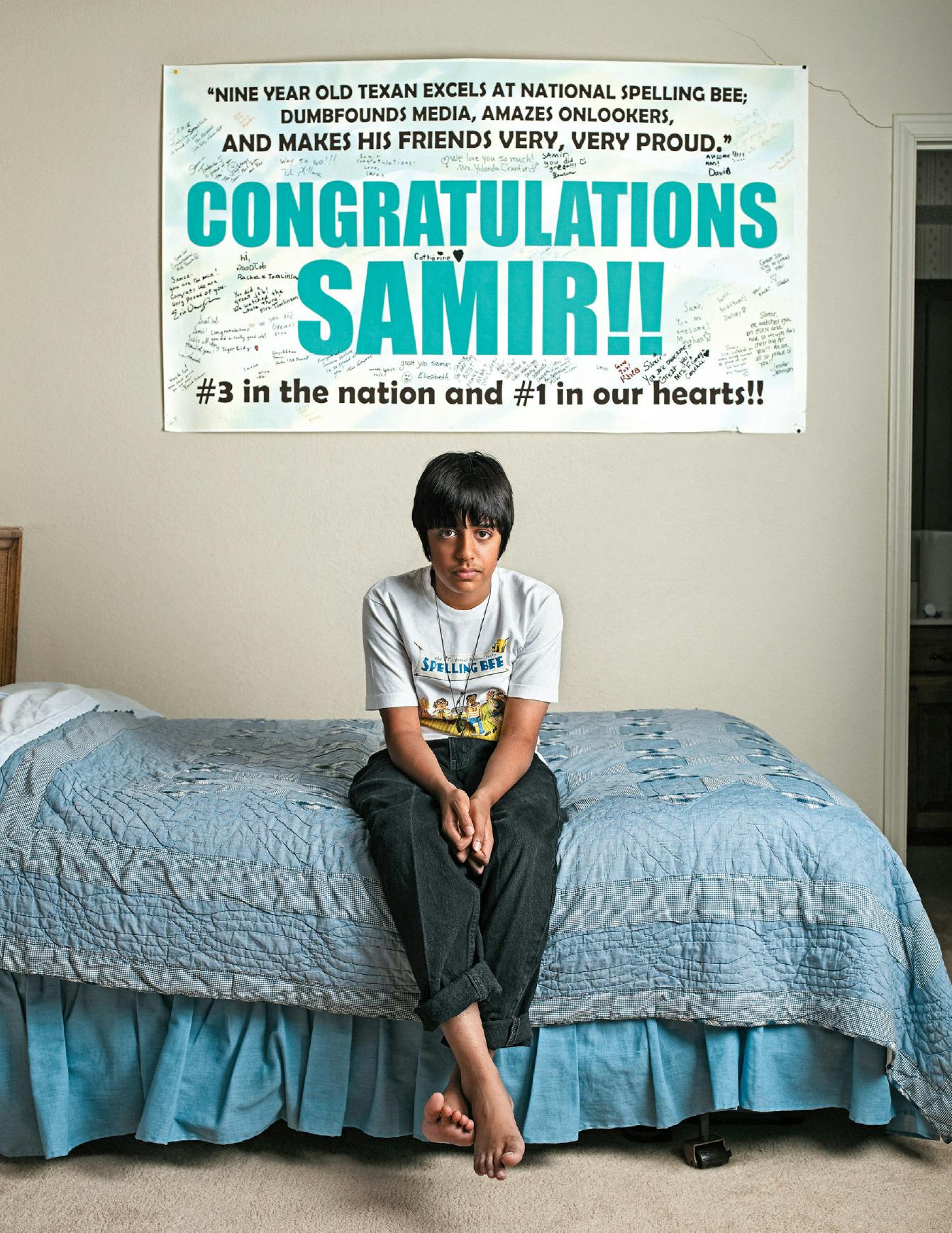

Samir doesn’t smile or shrug. Such assessments no longer faze him. Since 2003, he has been at the center of more media attention than any speller in history who’s never actually won the national bee. By age ten, he was already legendary enough to be the subject of an entire chapter in a book about spelling bees. Following the 2003 bee, Samir found fame as a “lifeline” on televised celebrity spelling contests and now has devoted fans worldwide. He has rubbed elbows with politicians, actors, Olympians, and enough notables to fill his book of autographs. Women approach him in supermarkets; bee nuts write about him online, dissecting his record, calculating his proficiency. In the run-up to this year’s bee, one blog posted a photo of Samir picking out his official polo shirt.

Samir’s string of four consecutive high-profile losses is part of what accounts for the interest. Analysts compare him to challenged sports legends and teams who never win the big one, like Michelle Kwan or the Buffalo Bills (God help him). He’s been devastated after every loss, trying desperately to wrap his head around defeat. Floyd Patterson, who used to sneak out of stadiums after losing boxing matches wearing a fake mustache and glasses, once said that anyone can be a good winner. “It’s in defeat,” Patterson observed, “that a man reveals himself.” Samir, of course, is not a man. He is a kid, and every year after hearing the dreaded ding that indicates an incorrect spelling, he has done what all kids do when the world doesn’t make any sense: He has cried a lot.

This year, he is once again the front-runner, and the blogs are all over him. “This is his fifth straight trip, and final one,” said the Bee Blog. “He’ll be too old next year.” (Next year, as a ninth-grader, he’ll be ineligible for the Scripps bee, which is limited to elementary and middle-schoolers.) Deadspin, a sports news site, warned, “Seriously, Samir Patel, if you lose, you’ve wasted your childhood . . . Last chance, kid: Don’t choke.”

By today, Samir has comfortably made it through the quarterfinals—in which 227 ten- to fifteen-year-old wunderkinder from all corners of the English-speaking world dinged out—by nailing “decor” (ornamentation) in round two, “trumpery” (deceit) in round three, and “sunglo” (a green Chinese tea) in round four. Fifty-nine spellers remain this Thursday as the semifinals begin. Now that the field is smaller, the commentators regale viewers with the contestants’ personal stories: a struggle with a brittle-bone disease, a mother in a coma.

Samir’s chances increase as one chair is left empty, then another, and another. Michael Girbino, a twelve-year-old with brown haired and eyeglasses that slip down his nose, looks wide-eyed and terrified when given the word “retiarius” (a Roman gladiator armed with a net and a trident). The elimination bell dings, and he thanks the judges as if he is grateful to leave the stage. Rebecca Rehberger, a fourteen-year-old from South Dakota who towers over the other spellers, scribbles her word, “siphonogamous” (adjective, “accomplishing fertilization by means of a pollen tube”), on the back of her placard and stares at it like a superhero utilizing her X-ray vision. At the sound of the ding, she looks as if she might crumble into a pile behind the microphone.

Finally, it is Samir’s turn. Rising from his chair, he confidently walks across the stoplight-red carpeting to center stage. He holds his hands together behind his back. He ignores the glare of the lights. He tunes out the cameras and everything buzzing around the stage. Previous experience has taught him that at this moment, he should aspire to be no more than a floating brain and mouth.

He faces the official pronouncer, Jacques Bailly, who sits at a navy-blue judges panel. The sounds of the word come rolling out of Bailly’s mouth with precise enunciation: “‘klev-es.’”

Ah, Samir thinks, I know this one.

English is one of the most complicated, untamable languages in recorded human history. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged, the official dictionary of the bee, lists more than 476,000 English words. Compare that with roughly 100,000 words in French or 200,000 in German. A mongrel tongue like no other, English began as a wholly Germanic language and then welcomed a massive infusion of French (due, initially, to the Norman conquest of 1066), then Latin (because it was the language of the church and of higher learning) and Greek (mainly for scientific terms). And when the colonialist period began, English pillaged the world’s languages for their treasures (“avocado,” “raccoon,” and so on). Other words were just invented out of thin air. Shakespeare alone coined more than 1,500 words, and these days we’re adding as many as 20,000 a year (“blog,” “d’oh,” “ringtone”). On the language farm, English is a big fat pig.

Is it any wonder a sixth-grader holding a spelling workbook looks so pitiful? Words with practically the same etymology often have very different spellings. The Latin root gentilis, for example, produced “gentle,” “gentile,” and “genteel.” A keen eye capable of detecting emerging patterns is quickly disrupted by interference. Pronunciation can give a speller hints, but as Bill Bryson pointed out in his 1990 book, Mother Tongue, English possesses more sounds than almost any other language: at least 44, compared with about 20 in Italian or just 13 in Hawaiian. Spelling, in most other languages, is simple: Sound it out. A Spanish spelling contest would be a joke.

English’s inconsistencies didn’t bother anyone who spoke the language a few hundred years ago, since there was no uniform spelling. The idea of dictating language seemed as silly as policing hairstyles. While France and Italy assembled academies to act as caretakers of their languages, England considered the idea, then nixed it. It was decided that a language belonged to those who spoke it and not to a government. As a result, even after the printing press necessitated standardized spelling, the process was painfully slow. Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall of Hard Usual English Words, a 2,543-word volume published in 1604 and widely considered to be the first dictionary of English, spells “words” two ways on the title page (“wordes” and “words”). No wonder Samuel Johnson’s 42,773-word Dictionary of the English Language, completed in 1755, was a big deal.

English spelling like Johnson’s, which retained the u in “honour” and the re in “theatre,” chafed the founders of the United States. A more phonetic and Americanized English was required to set the New World apart from the Old. Benjamin Franklin suggested a whole new alphabet, complete with six new characters, an idea that was as well received at the time as it would be now. The massive undertaking of systematizing American spelling finally found its champion in the self-righteous, hardworking Noah Webster, who, in 1828, finished a 70,000-word compendium that caused his compatriots’ hearts to swell: the American Dictionary of the English Language.

It was during this time that the spelling bee phenomenon was born. James Maguire explains in American Bee: The National Spelling Bee and the Culture of Word Nerds that young Puritans and immigrants wanting to show themselves as educated began gathering together for “spelling matches” in schoolhouses. By 1875, the president of the American Philological Association was declaring these contests an “epidemic.” An 1877 edition of the New York Times reported that, following a heated spelling match, two female contestants had gotten into a catfight, resulting in five days of jail time. Drama aside, these showdowns were relatively small affairs. The spelling bee as we know it today didn’t begin until 1925. The first national bee was sponsored by the Louisville Courier-Journal. More than two million kids entered. Competition began on the local and state levels, and eventually the number of contestants was pared down to nine for the finals in Washington, D.C. The first spelling bee champion, eleven-year-old Frank Neuhauser, of Louisville, won by spelling the word “gladiolus” (a genus of plants native chiefly to Africa). As of last year, the non-agenarian still grew them in his garden.

Now that English is spoken by roughly a third of the world, bee competition is much stiffer. More than two hundred kids make it to the Scripps nationals, sponsored by 267 organizations in the United States, Europe, Canada, New Zealand, Guam, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the Bahamas, and American Samoa. These kids are highly trained. They memorize bee workbooks and tirelessly study the ten-and-a-half-pound, three-and-a-half-inch-thick Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged, and its addenda, until they can spell “cwm” and “geeldikkop” without hesitation. Their determination is great. Many have coaches. The pressure, not surprisingly, has risen in equal measure with the degree of their preparation. In 2004, upon hearing that his word was “alopecoid” (like a fox), Akshay Buddiga, of Colorado Springs, asked for the definition, origin, and pronounciation, thought hard for thirty seconds, and then fainted—only to come around, stagger back to the microphone, and spell it correctly.

The rise of the spelling bee has been somewhat unbelievable. The past six years have witnessed a bee novel (Myla Goldberg’s Bee Season) that became a bee movie, a bee documentary (Spellbound), an off-Off-Broadway bee play (C-R-E-P-U-S-C-U-L-E), a Broadway bee musical (The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee), another bee movie (Akeelah and the Bee), and a serious work of bee nonfiction (Maguire’s American Bee). In 2006 the bee had become a big enough deal that ABC was delivering the broadcast of the finals in prime time. By then, lucky for the network, there was already a bee star: Samir Patel.

Samir is a root-word man, which, in the spelling world, is akin to calling him a purist. Win or lose, he loves to spell; he gets spelling. This type of natural ability is thrilling to see in any competitor, but the delight is compounded when the competitor is tiny. At the 2004 nationals, at age ten, Samir was given the word “corposant.” “Does it come from the Latin root corpus, meaning ‘body’?” Yes, it did. “Does it come from the Latin root corpusc, meaning ‘body’?” That root wasn’t listed. “Corpisarae, ‘to become body’?” That root wasn’t listed either. Samir smiled and asked, “Could I be on the right track?” He had been spelling competitively for only three years.

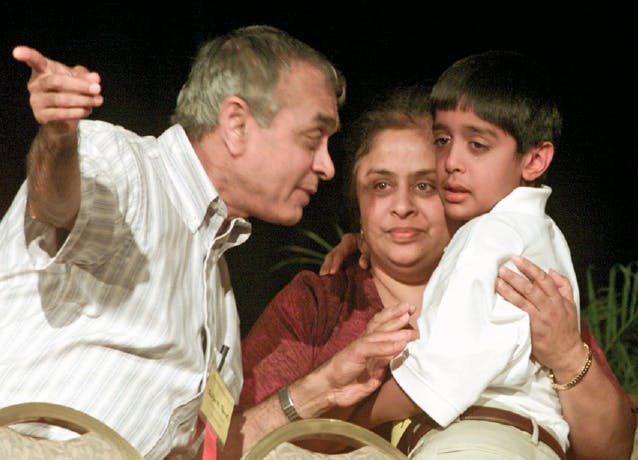

But let’s be honest. To some extent, Samir owes his orthographic success to his parents. When his father, Sudhir, first came to the U.S. from India as an engineering student in 1969, he landed in San Francisco. Sudhir, whose first language was Gujarati, a language descending from Sanskrit, was barely able to distinguish “hippie” from “hippo.” But by the mid-eighties, he had established his engineering career in Colleyville, and in 1989 he used his charm and his acquired proficiency in English-letter correspondence to convince a young electrical engineer living in India to move to the U.S. and be his wife.

This was no small task. A native English speaker raised in London and living in India, Jyoti was not an easy person to impress, but she was won over by Sudhir’s warm sense of humor. After she had Samir, she evaluated the Colleyville kindergartens and decided that a child who could read and do basic math needed more than the public schools could provide. So she began homeschooling him.

When Samir was five, he became intrigued with spelling. “I know how to spell ‘elephant,’” he said.

“All right,” Jyoti said.

“E-l-e-f-a-n-t,” he said.

“That’s a good try,” Jyoti said. “You’ve learned your phonics very well. But this is one of the words not spelled the way it sounds. It has a ph, like ‘phone.’”

Samir was crushed. And yet a speller was born. When the Patels’ local temple hosted a little spelling bee put on by an Indian American group called the North South Foundation, Samir entered and won fourth place. Although he hadn’t made the top three, the foundation invited him to participate in its small national bee because he was so young. Samir agreed. He hadn’t even studied, but against kids twice his age, he won.

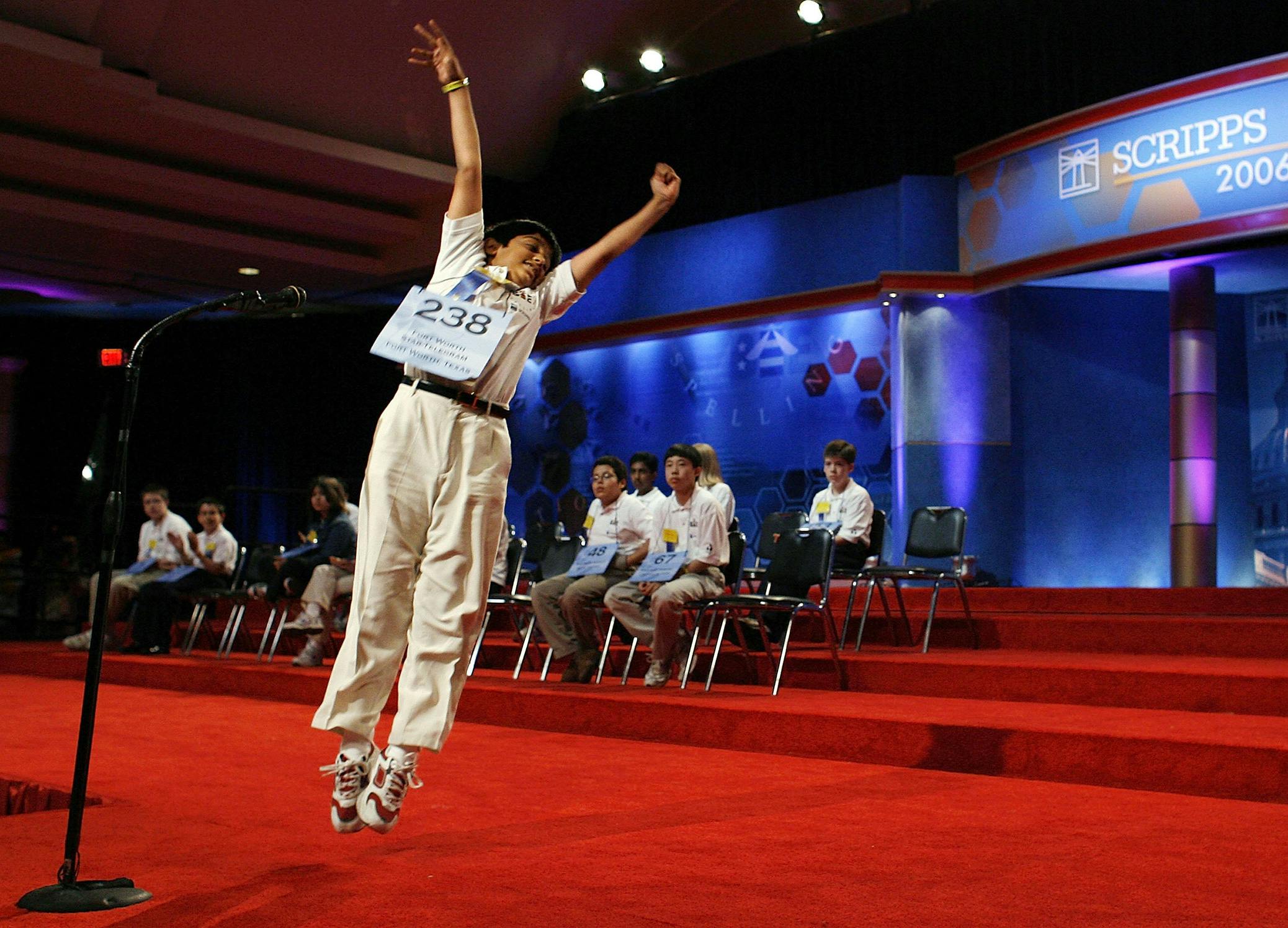

What could Samir do with some real preparation? In 2002, at age eight, he memorized 3,800 words from a study guide and took a shot at the regional Scripps bee in Fort Worth. He misheard his word and was eliminated, but he bounced back by digging into a consolidated word list disseminated by Scripps that cataloged 23,000 words from spelling bees dating back to the fifties. And he studied roots. “Use your memory power only for those words that are obscure or don’t follow certain patterns,” his mother told him. When he won the 2003 regional bee, he jumped off the stage.

In the national Scripps bee that year, Samir was a curiosity, bending the microphone down to rattle off his word and then walking back to his seat before the judges could even tell him whether he was right or wrong. He was too naive to be nervous. Given the word “tocopherol,” he asked if it was a compound occurring in vitamins. Informed that it was, he pumped his fists, then spelled it correctly. While the other kids tensed in the spotlight, standing at the microphone as if before a firing squad, Samir seemed entirely unperturbed. At one point he joked, “Is it just my luck, or am I getting all the French words?”

The 2003 national bee came down to Samir and just two other finalists. Jyoti and Sudhir were stunned. So was the audience. No matter the results, this was an amazing accomplishment for a young first-timer. Yet when Samir was taken down by “boudin” (forcemeat shaped like a sausage and served as an entrée), he was a wreck. He didn’t care that he was the youngest competitor in Scripps history to get as high as third place. He had assumed he’d win it all. Had he been eliminated in the quarterfinals, he would have been ushered offstage to a “comfort room,” where he could have calmed down privately next to a box of Kleenex and a plate of cookies. But so narrowly missing the title meant that he had to muster up the courage to face defeat with cameras capturing every tear.

He did not know it then, but his endearing performance in the bee would soon make him famous. A British television producer thought Samir was cute and asked him to be on a show called Daisy Daisy. Over the next few years he would be invited to England, Australia, and New Zealand to be a lifeline, or “human spell-check,” as he called it, on celebrity spelling game shows. Samir reveled in the attention. Once, when a contestant hesitated to go with Samir’s guess, he looked amused, then cupped his hands around his mouth and whispered loudly, “I’m right!”

Still, Samir was determined to feel the heft of the giant Scripps gold cup. It was around this time, between the 2003 and 2004 bees, that spelling became hard work. Jyoti and Sudhir began making a list of words that Samir needed to study. Going through a digital edition of Webster’s, Jyoti would quiz Samir and write down the words he missed; Sudhir would punch them into a spreadsheet so they could be randomized.

But preparation is not a guarantee. Fortune’s presence looms over all contests. A soccer goalie slips on a patch of mud and misses the ball; a spin on a basketball causes it to bounce off the rim. As a root speller, Samir always ran the risk of encountering a word for which the possible etymologies were multiple. In the 2004 nationals, he stumbled on just such a word, “corposant,” and placed twenty-seventh overall. The next year, etymological obscurity was to blame. He finished in second place—so close!—after dinging out on “roscian,” an adjective derived from a proper name, Quintus Roscius Gallus, a Roman actor. How could this be?

There was only one answer, according to Samir: luck. Luck practically manifested itself as a being in the Patel household, eating at the dinner table, sitting on Samir’s desk. “It’s the luck of the draw” was a phrase he repeated often. “I’ve been working at this for so many years, I just really want to win,” he told the Star-Telegram. “It’s basically my life now. But you can know all the words in the spelling bee except the one they ask you, and then you lose.” He found motivation in Louis Pasteur’s quote “Chance favors the prepared mind” and soldiered on. But the inspiration of the quotation didn’t come without a sting.

On the first day of the 2006 nationals, Samir was like an immovable object standing between the gold cup and the rest of the spellers, but he was now so nervous he could barely choke down his chocolate milk at breakfast and finished only part of his fish and chips at lunch. He started off well, correctly spelling “adiaphorism” (indifference concerning religious or theological matters) and “grandrelle” (a yarn usually having two plies of different colors). On the second and final day, he nailed “intarsia” (a mosaic usually of small pieces of wood used for decorations popular in fifteenth-century Italy). His momentum was building. Faced with “saponin” (any of numerous glycosides that occur in many plants that are characterized by their properties of foaming in water solution), Samir asked, “Does it come from the Latin and French root sapon, meaning ‘soap’?” After spelling “thymiaterion” (a vessel for burning incense), he leaped into the air. And then, in the seventh round, they gave him “eremacausis.”

“Eremacausis” is a unique word. A noun defined as “the gradual oxidation of organic matter from exposure to air and moisture,” it is derived from the Greek roots erema (“gently,” “softly,” or “slowly”) and kausis (“to burn”). “Eremacausis” is the single time the root erema appears in Webster’s. It seemed like a cruel joke for a root-word speller. There are lots of words with “erem” in them that stem from the Greek root eremos (“lonely” or “solitary”). Samir asked to hear the definition several times.

He wanted to know if it came from aero, meaning “air.” The judges said they did not see that root listed. He sighed, buried his face in his hands, and asked for a minute of “bonus time,” which spellers can use only once in the entire competition. Out in the audience, Jyoti braced herself.

“Does not come from air,” Samir whispered repeatedly. “Does not come from air.” When a bell rang, indicating that his minute of bonus time was up, a judge said, “Samir, it’s finish time.” The pit of his stomach twisted as he spelled “a-e-r-o-m-o-c-a-u-s-i-s.” There was a pause, then the ding of the elimination bell and a gasp from the audience.

Samir walked off the stage in tears, more disappointed than he had been any other year. He had pushed himself like a marathon runner in the final stretch. “You tried,” Jyoti said, looking to cheer him up. But Samir was inconsolable. After some time in the comfort room, Jyoti and Sudhir took him to their hotel room so he could wind down. Like any competitor who had sacrificed and come up short, he asked himself the inevitable question: Why am I doing this? “No matter how hard I study, it’s not affecting my performance,” he told his parents. “I could have gone in, not studied a single bit, and I would have the same results.”

He wanted to get back to a normal life, watching Dallas Cowboys games and hanging out with his friends. “Can’t we do this next year just a little bit?” he asked. “Like, let’s say, an hour or two a day? Not, like, try and really study-study for it?” He was interested in alternative medicine and had begun making teas and concoctions. He had been wanting to enter some math competitions—he was great at math. A speller applying himself to math found its patterns so beautifully predictable.

These distractions kept him safe from the biggest fear of all, the possibility that he’d lose one last time. And then what? Many people take decades to learn how to accept an unwanted fate, if they ever accept it at all. Ask a politician who has lost an election and spiraled into depression. Ask a football player who has lost the Rose Bowl and spent the remainder of his life believing everything would have been better, the sky a little bluer, if only he had won. Navigating directly through the worst-case scenario tests cowardice at its most basic level, and when a game has woven itself into a competitor’s identity, the stakes can be blinding enough for him to create excuses with acts of laziness and self-sabotage.

Jyoti knew this, and she was firm. “If you do it,” she said, “you have to give it your all.”

“Origin, definition, please?” Samir asks, turning his head slightly to the side of the microphone.

“‘Klev-es’ might be from Scandinavian,” Bailly says. “A ‘klev-es’ is ‘any various connections in which one part is fitted between the forked ends of another and fastened by means of a bolt or pin passing through the forked ends.’ ‘Klev-es.’”

It has to be c-l-e-v-i-s, Samir thinks. That schwa sound there at the end, though—what was that? He has begun to slouch, and he straightens up. “Repeat the origin?” he asks.

“Uh, probably Scandinavian,” Bailly says.

“Are there any alternate definitions?” Samir asks.

Brian Sietsema, the associate pronouncer, reads from his dictionary: “A ‘klev-es’ can also mean ‘a fitting for attaching or suspending parts as a cable to another structural member of a bridge or a hangar for supporting pipe that consists usually of a U-shaped piece of metal with the ends drilled to receive a pin or bolt.’”

Samir stretches his arms behind his back and bows his chest slightly. Scandinavian? No—probably Scandinavian? Maybe it’s not c-l-e-v-i-s. Don’t rush. Just a floating brain and mouth.

“Okay,” he says. “‘Klev-es.’ C-l-e-v-i-c-e. ‘Klev-es.’”

There is a pause while Samir looks at the judges. And then the ding of the bell.

A month later, the Patels’ brick home in Colleyville was as quiet as a library. Samir entered the room barefoot, wearing black jeans and an orange-and-red plaid short-sleeve shirt buttoned all the way to the top. He sat on his heels on one of a series of long leather couches that lined the room, inching closer to the edge of the cushion as he engaged in conversation.

“There are a lot of movies I haven’t seen,” Samir said. “I’ve been watching The Terminator and Mission: Impossible. I like Spider-Man, you know. They’re going to show the new Harry Potter movie at the IMAX Theater, so I’m gonna go see that.”

“We have been working hard for competitions in the last five years,” said Jyoti, sitting on another of the leather couches. “So we just decided to really chill. He’s been watching a movie every night.”

Dwelling on the negative is not a Patel trait. When recalling the past five years, the family would prefer to discuss Samir’s cameo on Broadway in The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee or his recent appearance on the Food Network’s Dinner: Impossible or the time he chatted backstage on the set of The Great Celebrity Spelling Bee with Alice Cooper, who gave him a CD and then assured Sudhir, “This doesn’t have any bad words in it.” (Cooper did not fare well in the celebrity bee, dinging out on “odyssey.”) And anyway, Samir would rather look to the future. He’s focusing on math competitions. He’ll be taking some college courses (“I looked at my biology textbook; I am, like, ‘Wow. This is really deep and interesting’”). He’ll continue serving as an official pronouncer for the North South Foundation spelling bee (something he’s done since 2006). The Van Cliburn Foundation has invited him to speak at schools all around the district as part of a program called Musical Awakenings that relates spelling to music.

“Everything is not about competition,” Jyoti said.

“I started swimming for the fun of it and for exercise a couple years ago,” Samir said. “I was in my first swim meet, and I got really tired, and I didn’t get a great time, but I think I’ll continue just for fun. I don’t think I’ll be a great swimmer, but, you know, it’s one of those things that you do.”

But in the bee postmortem, mother and son traded barbs like an old married couple. “To this day I will maintain that last year, 2006, was extremely unfair,” Jyoti said. “The word he received was not fair in that round, and he did get cheated out of achieving the position he deserved. This year it was in his hands. He ruined it.”

“Because this year I knew the word,” Samir said without flinching.

“That’s where we’re having a bit of a tiff,” Jyoti said with a laugh. “I’m still mad at him.”

Samir coolly explained: “She feels, for some odd reason, that you cannot second-guess yourself. She doesn’t believe that’s possible. Which is obviously incorrect. So that’s where we’re having arguments. And it’s, like, in 2006, okay, I agree that the word was unfair, but I think you just have to go into competition realizing that it is not going to be completely fair.” He shrugged. “So that’s just my view on it.”

“If you really knew the word, you wouldn’t have guessed at it,” Jyoti said.

“I didn’t guess at it, actually,” Samir said. “I knew it, and I just second-guessed myself. That’s why we’re having arguments. She just—I don’t know if it’s something she learned in school, but she just seems to feel that you cannot forget something and you cannot second-guess yourself.”

“Not at such an important point in the competition,” Jyoti said. “That’s my view.”

“So, as you can see,” Samir said, “that’s mother and son, teacher and student, having different views.”

While Jyoti was careful not to hurt Samir, she was as blunt as any coach about her own feelings; each year that he lost, the pain stung more. “I kept on going because my whole point is to teach him to persevere,” she said. “But it was that much harder.” This being his final year, it was the worst. “I’m still not over this one,” she said.

“‘Klev-es’ is c-l-e-v-i-s,” says Bailly.

Samir stares out from the stage. He is too shocked, at first, to feel anything. He looks down for a second, almost nodding, then he quickly turns from the microphone and walks, almost goose-stepping, offstage. He shakes hands with the bee escort while the audience and all the kids on the stage rise from their chairs and give him a thundering standing ovation. Some are laughing with disbelief, others are slack-jawed, others look panicked and confused. The king is dead.

“That is absolutely shocking,” says one ESPN anchor. “I think it’s going to take a few moments for everyone to regain their composure after that,” her partner responds. (Later on, Stuart Scott would tell a blogger from the Washington Post, “It’s like the Mavericks losing in the first round. That’s exactly what it is, the Mavericks losing in the first round this year of the NBA playoffs.”)

While Jyoti sends in an appeal to the judges to be sure Samir received all the required pronunciations (he did), Sudhir rushes through the audience to join his son in the comfort room. He arrives, fearing the worst, to find Samir strangely dry-eyed. He doesn’t want a glass of water or a cookie or a hug.

At the end of the day, thirteen-year-old Evan O’Dorney, from Danville, California, will win the bee and say this about his hard-earned prize: “Spelling is just a bunch of memorization.” But perspective is easy for the winner. Various emotions will wash over Samir in the days and weeks ahead—anger with himself for missing a word he knew, disappointment, some heartbreak. But it’s funny. These feelings don’t scare him anymore. He doesn’t need a brave face. He doesn’t yearn for a trapdoor to escape.

“Do you want to take a minute before going out there?” Sudhir asks.

“No, Dad, I’m fine,” Samir says.

“Okay, there are hordes of people out there. Cameras and reporters,” Sudhir says.

And then, right there, it happens. With his hand on the doorknob, as he’s about to go out and face the bright glare of public scrutiny, Samir turns to his father, at peace in the moment that has made him a man.

“No problem,” he says. “I’ll handle it.”

- More About:

- Longreads

- Colleyville