Last New Year’s Eve George Strait sang his smooth honky-tonk and Western swing before a sellout crowd at Reunion Arena in Dallas, then spent a quiet night with his family. Just a few blocks across town, at Dallas Alley, Steve Earle punched out his set of rocking country, then spent most of the night in jail on charges of aggravated assault on a police officer. In a nutshell, that is country music these days in Texas. The Lone Star State is the most fertile breeding ground for the so-called New Traditionalists, an eclectic grouping of younger performers distinguished largely by their opposition to the established but faltering Nashville-created Urban Cowboy movement and diverse enough to include both George Strait and Steve Earle, different as they may seem.

Not only is country music no longer what it used to be; it is often no longer even what it appears to be. Originally the exclusive, informal language of dispossessed rural Americans, country music started to become suburban, middle-aged, and polyester with the rise of the Nashville Sound in the late fifties. Within two decades, country had become geriatric and formulaic, a blue hairdo undergoing constant gussying up. The outlaw movement, also known as progressive country, was an attempt by Texans Willie and Waylon and the boys to create a seventies version of its original bare-bones sound and rugged-individualist stance. The movement succeeded briefly but served more to point out how much the country audience could be expanded with proper marketing. Nashville latched on to a good thing with the Urban Cowboy, another Texas phenomenon, a style that succeeded in erasing most boundaries between pop and country while making stars of such lowest-common-denominator performers as Texan Kenny Rogers.

When that baroque sound boomed in the early eighties, Nashville made the mistake of assuming it would always do so. By 1985, though, pop faddists had deserted country and crossover acts were no longer crossing over—that once-promising brand of country-pop ultimately pleased fans of neither camp, and the industry staggered. Enter, in the last three years or so, the New Traditionalists.

The movement’s very name suggests the kind of identity crisis that had struck country music—how can something sound new and traditional at the same time? But the face of the music and the audience had been so altered—it was just as appropriate for a Dallas banker to like country music as it was for a New York stockbroker—that the new wave of performers reflected that split personality. The term “country” needed no longer to refer to a particular background or way of life; it began to refer only to the sound of the music. Some of the New Traditionalists have rural backgrounds, some don’t. Some actually ply traditional sounds, some don’t. What matters is that the musicians are young, successful, and loyal to pre-Urban Cowboy motifs. The two extremes of that movement—in Texas and in the nation—are represented by George Strait, a South Texan now living in San Antonio, and Steve Earle, who grew up mainly around the Alamo City but has called Nashville his home for more than a decade.

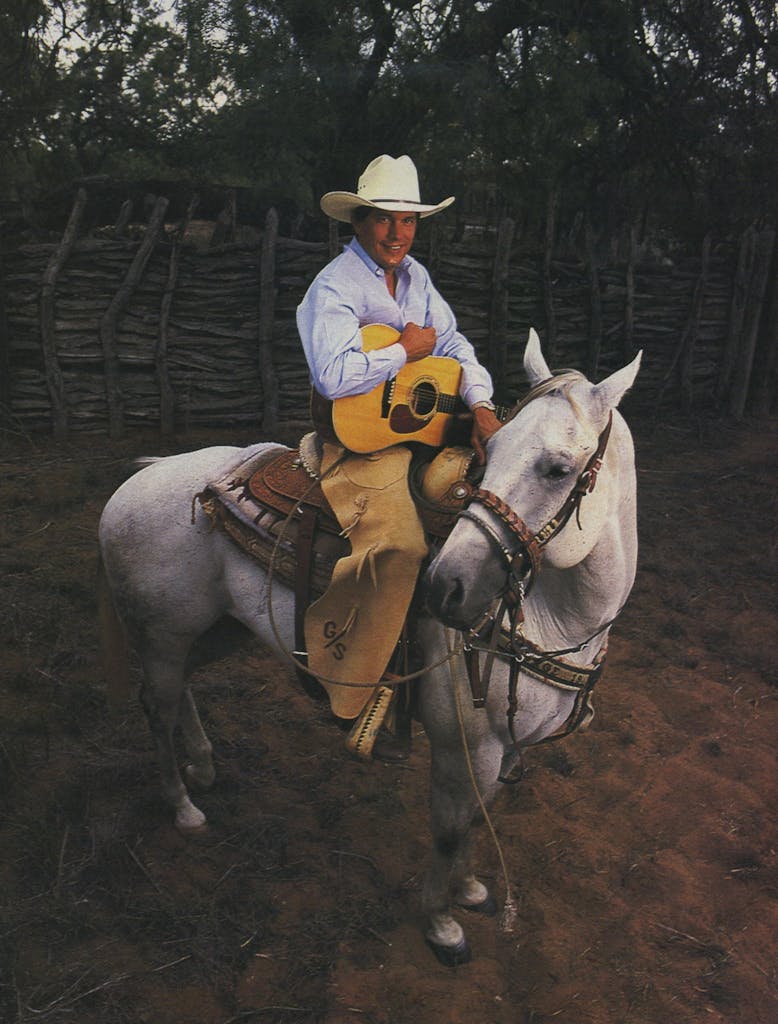

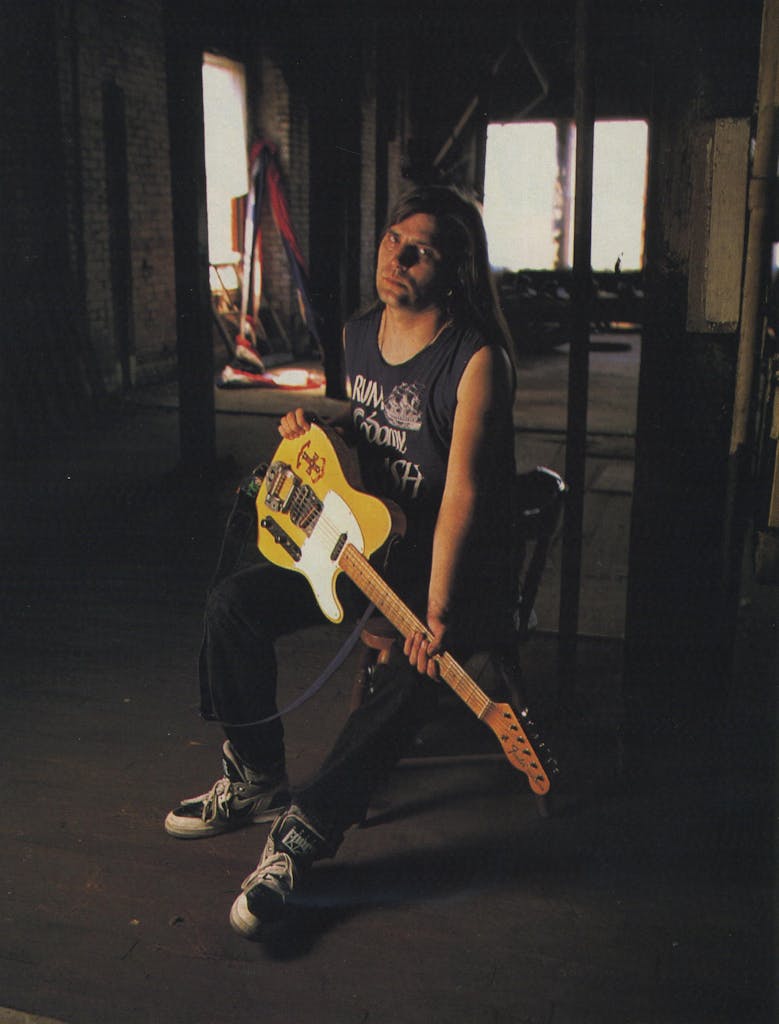

You couldn’t ask for a more unlikely set of bookends. Strait is firmly rooted in traditional Texas country while Earle is more like the mid-seventies Austin outlaws, who fused urban folk with country, gave it “meaningful” lyrics, and yoked it all to rock rhythms. Strait is an interpreter while Earle writes most of his own material. Strait always appears onstage in starched jeans and dress shirts with a white hat —your basic clean-cut young cattleman’s look—while Earle favors well-worn T-shirts, jeans, and a ragged leather or Levi jacket, his shoulder-length hair often held back with a headband. Strait, at 36, has been married to his high school sweetheart for his entire adult life while Earle, at 33, is in the throes of his fourth divorce.

Strait emerged in 1981, when country was at its most florid, and his honky-tonk love songs, with their references to Texas, cut through most of the era’s radio fare. From the beginning he was as popular with teenage girls as with their mothers—and that isn’t supposed to happen in country music. He is an intensely private man known for granting few interviews and saying little when he agrees to talk. Since his thirteen-year-old daughter was killed in a freak one-car accident in 1986, he has become even more reticent. Yet he remains friendly as long as the subject doesn’t get too personal. “My opinions are my opinions,” he declares, “and I don’t feel like a good place for them is in some magazine for other people to read.”

The hat he wears onstage is such a trademark that when he once tried to visit an Asleep at the Wheel gig without it, he was refused entry to the backstage area because the guard didn’t recognize him. The comparison to Bob Wills, one of his idols, has often been made, but watching Strait work a crowd recently at the International Hotel in Las Vegas brings a better analogy to mind. Wills, after all, was flamboyant, irascible, unpredictable, hard-drinking—none of which describes the strong, silent Strait. No, he is more like the clean-living, good-looking hero in the white hat—Gene Autry, say—who does his job efficiently and with a smile and then moves on. Once an image country singers cultivated, it seems old-fashioned today. And in Strait’s case, there’s really nothing to suggest it’s an act.

“I’ve always been the same,” Strait says between shows in Vegas, sipping a drink at the bar in his spacious dressing room as his wife, Norma, attends to seven-year-old George Junior (“Bubba”). “I just want people to go out and have a good time listening to my music. The image deal—that’s for the birds. I’m not the first guy who’s ever worn a hat like this or worn starched Wranglers.”

Where George Strait comes from, a man goes about his business with minimal fuss. He was born in Poteet because there was no hospital in Pleasanton, where his parents lived. His folks divorced when he was still in grade school, and he was reared mainly in Pearsall by his father (a junior high math teacher) and his father’s parents, who ranched outside Big Wells. Strait recalls an archetypal small-town childhood: lots of football and baseball, bad junior high rock bands playing English Invasion hits, plywood-covered caves dug in the hard brush-country dirt in which he and his friends could go to try out cigarettes (he’s a nonsmoker today). There are suggestions that all was not idyllic. “There’s a lot of good memories, a lot of not-so-good memories, but… I’m trying to think of a good one,” he laughs. The closest he comes to revealing an unruly streak is the concession that he and Norma had to marry twice—after eloping to Mexico they repeated the ceremony in a Texas church to pacify their parents.

But he never considered music as a career until the Army sent him to Hawaii and he won a spot in a military country band. When he returned to Texas in 1975, he registered at Southwest Texas State University because it would leave him more free time for music. When he hooked up in San Marcos with the Ace in the Hole Band, he told them he intended to conquer Nashville as a solo singer, not as front man for a group; it is a tribute to his diplomacy that when he did so in 1981, three of the four members stuck with him.

Thirty miles up the road in Austin, outlaw was the thing. Strait completely ignored the style, sticking with the honky-tonk and Western-swing dance music of Bob Wills and Ray Price, Hank Williams and Ernest Tubb, Merle Haggard and George Jones. He sang the kind of corny wordplay that had once been country’s stock in trade (“Every time you throw dirt on that girl/You lose a little ground”), love songs and weepers like “Unwound” or “The Fireman,” and pop-flavored modern ballads that somehow still sounded traditional. He made few references to the liquor and rambling aspects of the honky-tonk life—not part of his own life anyway—but he did throw in an occasional beer-drinking song. He stood his ground, and sure enough, country music came back to him. Strait’s record sales now stand at 12 million, and it has been four years since he was booked into a dance hall or club; nowadays he plays civic centers, sports arenas, and big outdoor affairs.

Strait’s manager, Erv Woolsey, a former San Marcos club owner, says that Strait watches over the details of his career more closely than do most stars. Strait believes the key to success in the music business is having the right songs, and he will tell you that he likes the spotlight onstage even though he doesn’t like the demands that stardom makes on him and his family, such as interviews and autograph-signing sessions. He would rather talk about golf (he has a twelve handicap) or his ranch near Encinal (which he’ll stock with cattle as soon as the price goes down) or hunting (especially the eighteen-point whitetail he shot last year). But after that, he would prefer you knew nothing about him except his fine voice and songs and the sprightly twin fiddles and whining steel guitar of his backup band.

Steve Earle, on the other hand, will be happy to talk your ears off about nearly anything from the details of his four divorces and two kids to some herculean bouts with drink and drugs to the state of union-busting in the Reagan era. Earle is a man of words, a fan of Hemingway and Faulkner with few ties to traditional country. He came to the music business by way of the urban folk scene. His songs are meant to be “literature that you can consume while you’re driving your car.”

Attuned to Bruce Springsteen as well as Hank Williams, Earle writes thumping rockers like “San Antonio Girl” and introspective ballads like “My Old Friend the Blues” and “I Ain’t Never Been Satisfied.” But the middle-class son of an air-traffic controller is best known for such populist outbursts of blue-collar loss and longing as “Someday,” in which a filling-station attendant dreams of fleeing his nondescript hometown on the interstate. The limits placed on such people is a theme Earle returns to again and again. “Good Ol’ Boy (Gettin’ Tough)” is told from the point of view of a man who married and bought a house with his G.I. loan, struggles to make payments on his pickup, and roars away weekends in beer joints, knowing that whatever release that brings him will evaporate Monday; “A Week of Living Dangerously” refers to a family man’s Boys Town fling and his return to more-conventional ways; and “No. 29” is about a former high school football star adjusting to the hard truth that his best days are behind him. That is not the standard fare of contemporary country music, and as his music moves ever closer to rock, Earle is the first to acknowledge it.

“But I think what I’m doing is very true to the traditions of country music in that country music was totally unafraid of any subject matter, and that’s one tradition that died. Nowadays you couldn’t get ‘Long Black Veil’ [Lefty Frizzell’s 1959 ghost story of adultery and murder] on the radio, simply because it talks about death,” he says, cruising outside Nashville at 85 miles per hour one afternoon in his ’87 Buick Regal. In the back seat, his girlfriend, an artist-and-repertory executive for a West Coast record company, banters with Justin, Steve’s six-year-old son, for whom his song “Little Rock and Roller” was written. The day before, Earle had returned home from a month in England, and he’s happy to be “back in a place where you can get a Dr Pepper.” Earle is on his way to the suburb of Franklin, where his ’67 Chevelle is being painted. At a cost of more than $15,000, he and a mechanic friend rebuilt the car to make it “more powerful than I have any business driving—it’s street-legal, but just barely,” Earle says. He also cosponsors a dirt-track racer, which he calls “a lot of fun because it’s totally outlaw; nobody sanctions dirt racing anymore.”

Such phrases could almost apply to Earle himself; at least that is how he has been perceived in Nashville for most of the decade. Though born in Virginia, he grew up mostly in and around San Antonio, running away from home for the first time when he was fourteen, moving out for good at sixteen. He played local coffeehouses for several years, mixing folk and country standards with his own earliest attempts at songwriting, then moved to Houston to get in on the last days of that city’s folk scene. There he met Townes Van Zandt, his idol, and Guy Clark, in whose band he later played bass.

When he hit Nashville in 1974, he was the youngest of a crop of folkish singer-songwriters dominated by Texans such as Clark and Van Zandt (and Jerry Jeff Walker, when he was in town). Earle kicked around as a sideman and a songwriter, subsisting on odd jobs and pass-the-hat solo gigs in local clubs. In 1978 he waited out a restrictive songwriting contract in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, for eighteen months. Back in Music City, he tried his hand briefly at writing hits for other artists, enjoying just enough success to keep himself afloat. In 1982 he took an unconvincing stab at rockabilly.

Meanwhile, the outlaw movement that had nurtured him had pretty much dissolved—the all-night parties and picking sessions had given way in Nashville to stolid careerism, only nobody seemed to have told scruffy Steve Earle, who, though ambitious, remained determined to make the system bend to him. He became known around town as being perhaps just a little too wild and unmanageable for someone with such a dismal commercial track record. So when Guitar Town, his 1986 solo debut, attracted critical raves and sold respectably, most of the country music world, especially radio, was caught off guard. Even today, Earle lives by the live show, and as his audience grows younger, he talks of giving up on country radio entirely. In fact, his new album, Copperhead Road, due out this month, is being released on Uni, MCA’s rock-oriented label based in New York.

Considered country largely because he lives and records in Nashville with country musicians, Earle thus remains something of an interloper in his hometown of fifteen years. He is enough of a Texan that when Justin was born in Nashville, Earle’s father sent him a can of Texas soil so that it would be the first earth the infant’s feet touched—just as when Steve was born in Virginia, his grandfather had done. Still, when Earle was in Mexico, he had written a song—he can’t recall the lyrics anymore —called “Texas Doesn’t Feel as Much Like Home.” He explains it today by saying, “It’s just one of those deals where the place you come from can become a handicap. I identify very much with being a Texan and probably always will, but I will probably always be an expatriate Texan, and I don’t know why.”

Which leads him naturally to a discussion of New Year’s Eve in Dallas, when his attempts to cool out a tipsy roadie led to a shoving match that ended, he says, when he was attacked from behind without warning by a Dallas police officer applying a choke hold with a nightstick. The officer denies having used a nightstick. Earle’s trial on the criminal charges has been postponed once already. The officer has filed a civil suit against the singer for injuries he claims to have sustained during the melee. Earle has filed a countersuit in federal court, claiming that his civil rights were violated and that he suffered permanent damage to his vocal cords as a result of the attack.

Obviously, that is not the sort of situation a George Strait is likely to find himself in. The Lone Star State’s two standard-bearers for contemporary country are irrefutable evidence that, to quote a song title from the late Ernest Tubb of Crisp, “There’s a Little Bit of Everything in Texas.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Steve Earle

- George Strait