This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Man, does he ever need a lawyer.” Dick DeGuerin thought this last March as he stared at the image of David Koresh on the television screen: a 33-year-old misfit holed up in a compound known as Ranch Apocalypse, surrounded by an army of federal agents. To DeGuerin, a man comfortable with his reputation as Texas’ best criminal defense attorney, that first notion led quite naturally to a second: “He needs me.”

Unbeknownst to DeGuerin, the same thought occurred to another great lawyer thirty years ago, prompted by the misdeeds of another Texas misfit. After witnessing Lee Harvey Oswald’s murder on television, Percy Foreman announced to the press, “I go where I’m needed most. And right now, I can’t think of anyone who needs my services more than Jack Ruby.”

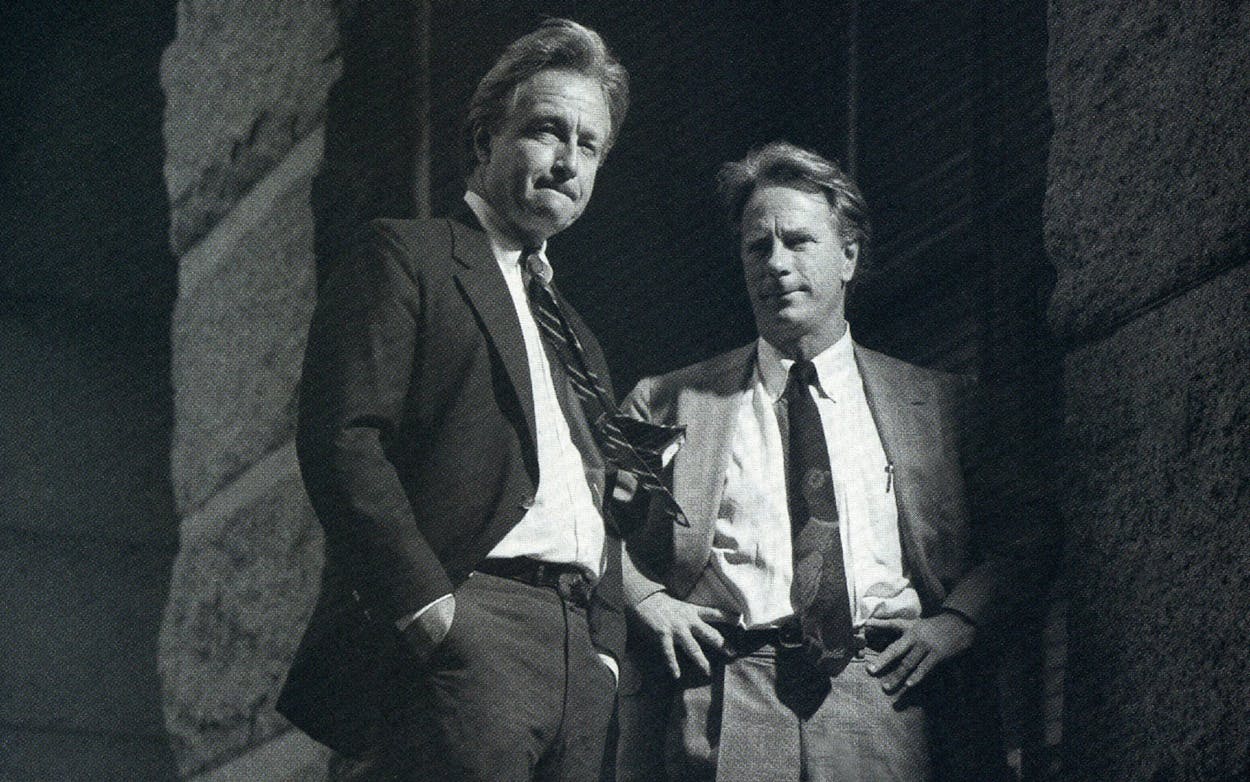

That DeGuerin would echo Foreman was fitting. Foreman had been his mentor, and since Foreman’s death in 1988, DeGuerin has made it a habit to ask himself, “What would Percy do?” whenever a new case crosses his path. DeGuerin does not doubt for a second that Foreman would have offered his services to David Koresh—and, for that matter, to Kay Bailey Hutchison, who has hired DeGuerin in the face of felony ethics indictments. The Hutchison trial stands to be one of the two most sensational courtroom spectacles in Texas this year. Competing with it for drama and headlines will be the trial of the Branch Davidian lieutenants, who happen to be represented by another Foreman protégé: Mike DeGeurin, Dick’s brother. (As a college student, Dick DeGuerin changed the spelling of his surname to the original French spelling.) Like his older brother, Mike DeGeurin is regarded as one of the state’s finest lawyers; like Dick, he habitually invokes the mentor’s wisdom. From 1976 until 1982, the old man and the brothers worked together under the same roof in downtown Houston. Inevitably, Dick, the rebellious prodigal son, left the demanding father figure in 1982 to seek out his own fame. Just as inevitably, Mike stayed behind and today still tends to the business and the honor of Foreman, DeGeurin, and Nugent.

Their apprenticeship is long behind them. Yet the state’s most famous sibling lawyers, in their distinctly separate ways, reflect the legacy of Percy Foreman, perhaps the greatest trial lawyer in Texas history and one of the very best who ever lived. By practicing The Law According to Foreman, the brothers have maintained a continuum spanning nearly seventy years of brilliant, often controversial criminal defense work in Houston. In the coming months, Dick DeGuerin’s representation of Kay Bailey Hutchison and Mike DeGeurin’s handling of the Branch Davidian case will underscore the differences in their styles and personalities. Yet beneath the strategy of each, one can expect to hear the Foreman credo: “You should never allow the defendant to be tried. Try someone else—the husband, the lover, the police or, if the case has social implications, society generally. But never the defendant.”

Seated at the conference room table in the Austin office of Kay Bailey Hutchison’s husband, Dick DeGuerin talks while eating his lunch, which today consists of Dots candy and coffee. (Tomorrow’s lunch will be popcorn and coffee.) His well-proportioned frame and youthful face suggest an imperviousness to long hours and dietary abuse. Both in appearance and conversation, the 52-year-old lawyer is engaging but always a little cool and loath to show his hand, even when the game is over. Today, however, he freely discusses his legal strategy for the defense of the embattled Senator Hutchison. “If [Travis County district attorney] Ronnie Earle is correct in his interpretation of what an officeholder cannot do,” he concludes in a rising voice, “then everybody who holds office is subject to being indicted. How do you decide whether speaking at a Republican women’s club is or is not state business? To try to enforce that kind of morality in the jury box, as opposed to the ballot box, is just improper. Even though Kay’s a very powerful person, she’s been terribly abused by those in power in the Travis County DA’s office.”

DeGuerin smiles. “And that’s my forte,” he says. “I like to help people who are being beat up on. I remember one time when I was eight and Mike was four and we were living in Austin and swimming in the West Enfield swimming pool, there was this big kid who stood on top of the pool ladder and wouldn’t let Mike get out. I went up to the big kid. And I held up my fist and I said, ‘You leave him alone.’ I see somebody get picked on, and that gets my juices flowing.”

Thirty years ago, as a University of Texas law student, DeGuerin watched Percy Foreman come to the rescue of a man the legal system was picking on. The defendant was a thoracic surgeon whose wife and two brothers sought to institutionalize him. Only Foreman stood between his client and the mental ward. The young law student could not take his eyes off the 61-year-old lawyer. Foreman was in every way a giant: six feet five, close to three hundred pounds, with hands like catchers’ mitts and a head one Houston lawyer described as “simply monstrous, the biggest in town.” The surgeon’s wife had hired two hotshot special prosecutors: Les Proctor, the former Travis County district attorney, and Frank Maloney, today a judge on the Court of Criminal Appeals. Foreman made them look like amateurs. Flaunting a giant horse syringe, the Houston lawyer declared that if the surgeon’s wife and brothers had their way, one of the great minds of medical science would, in the nuthouse, be reduced to gelatin. The jury found in favor of the surgeon, who left the courthouse with Foreman, along with several of Foreman’s attractive female admirers, in a long black Cadillac. Young Dick DeGuerin stood on the steps and watched them go, holding in his hands a Parade magazine cover story on Foreman, which the lawyer had autographed for him.

By that time, Percy Foreman had been defending accused criminals for 35 years. Soon he would take on the appeal of Jack Ruby’s case—though he later walked away from it in protest of Ruby’s meddlesome family. In 1966, in Florida’s Dade County Courthouse, he would successfully defend Candace Mossler and her nephew Melvin Lane Powers, who were accused of murdering Mossler’s multimillionaire husband. Through the Mossler case, and his later defense of Martin Luther King’s assassin, James Earl Ray, Percy Foreman would become a national figure. But the man 22-year-old Dick DeGuerin beheld was already a legend in Texas. Like every other dreamy-eyed law student, DeGuerin had read about Foreman’s rise from the East Texas obscurity of Bold Springs, a few miles down the road from Livingston. He knew that since Foreman began practicing law in 1927, he had defended hundreds of accused murderers (more than a thousand by the time of his death) and only one of those was executed by the state.

Foreman was an imposing presence, a massive figure in natty customized attire, his slicked-back hair spilling down into his fist of a face, his Zeus-like voice clapping off the courtroom walls. “The first time I saw him,” recalls Houston attorney Joe Jamail, “I thought, ‘My God, that’s what a lawyer’s supposed to look like.’ ” No one knew more about how to select a jury; former associate John Cutler says, “I used to hire a court reporter to take down his voir dire questions to prospective jurors just so I could study the transcript later and see how Percy did it.” (In addition to his instincts, Foreman relied on a few rules of thumb in jury selection: Blacks, Jews, and other groups who had faced oppression were often sympathetic; Germans and Scandinavians “have little understanding of mistakes”; and exacting professionals like accountants and engineers were similarly unforgiving.) Foreman, according to a former colleague, “was one of the few defense lawyers to realize that the DA was the enemy.” No one bullied him; on the contrary, some assistant DAs did anything to avoid facing him in the courtroom, while the more ambitious ones happily got trounced just for the learning experience. During one trial, when a prosecutor became overly emphatic about the location of a gunshot wound to the head, Foreman stood up and, with a red Magic Marker, drew a large circle in the prosecutor’s white hair, where it remained for the duration of the day.

In front of jurors, Foreman would sob, scream, or do whatever else it took to sway them. Above all, however, he prepared, briefing each criminal case as if it were an intricate civil proceeding. He knew the law, and he did the investigations himself. Sometimes a case required more courage than anything else, and Foreman had that as well. In the 1952 trial of an alleged gangland murderer, Foreman argued that the defendant’s confession had been beaten out of him by Harris County sheriff Buster Kern and Texas Ranger Johnny Klevenhagen, and was witnessed by a deputy named Kain. In his closing argument, Foreman brazenly pointed to Kern and Klevenhagen, who sat in the front row of the courtroom, and shouted, “Kern, Klevenhagen, and Kain! KKK! They ku-kluxed this defendant! They tortured him to make him confess! Who among you can say you, too, would not have confessed to this killing—innocent though you be—if these pistol-packing, blackjack-wearing, handcuff-carrying, booted and spurred officers of the so-called law had predetermined you guilty and decided you were going to confess?” As soon as the jury declared the defendant not guilty, the sheriff and the Ranger leapt over the railing and proceeded to maul Foreman, who was already using a crutch because of a sprained left knee. Upon his release from the hospital, the bruised and hobbled lawyer grinned and said to the press, “I harbor no malice toward these poor, misguided minions of the law.”

It was always a temptation to reduce the big man to a single comic-book dimension, but there was much more to Foreman than met the eye. True, he charged high fees, but never as enormous as reported: It was a tactic to screen out the nuisance cases, and he handled many clients for little or nothing. (He also enjoyed referring plum cases to attorneys he liked and wacko cases to those he despised.) His pride in his murder-case record was matched by his fervent moral opposition to capital punishment—which, he once caustically remarked, “should not only be on television but be sponsored by the Texas Power and Light Company, which supplies the juice.” And for all the millions he made in divorce cases, he forfeited millions more by turning such clients away. “In many cases,” says his former associate Lewis Dickson, “he set out after the husband with such an insulting fervor that he accomplished his ultimate purpose, which was to get them back together. He saved a lot of marriages.” In one such case, a wealthy River Oaks woman answered Foreman’s question “Why are you seeking a divorce?” with the answer “I’m just not happy.” Foreman roared, “You don’t need a lawyer! You need a pharmacist! You’ll never find someone who treats you as well as this man does! Now get out of my office!” The woman remains married to this day.

That first sight of Foreman in the courthouse dizzied Dick DeGuerin, but it did not change him overnight. He was a bright but easily bored young man, the kind of student who vexed teachers because he would not apply himself. His father, Elias McDowell DeGeurin, was an oil and gas lawyer and LBJ confidante who urged his son to pursue a career in politics, but all that glad-handing looked to be a bit much. Mainly he enjoyed reading Shakespeare, drinking beer, and visiting the Chicken Ranch whorehouse in La Grange. Upon graduating from the University of Texas, DeGuerin applied for a job at the FBI, which turned him down on the grounds that he had once been arrested for trying to climb a parade float that carried Governor Price Daniel. So he entered UT Law School, imagining himself as an international lawyer, chasing French girls and whatnot.

In 1965 DeGuerin got his law degree. He followed his law school buddies to Houston, where the action was, where Percy Foreman was. He sought employment from each of the big firms, who wanted experienced trial lawyers or top-of-the-class graduates. DeGuerin was neither. A family connection got him an interview with Harris County district attorney Frank Briscoe. The meeting went well, and DeGuerin was handed a formal application to fill out. The back page, which questioned the applicant’s criminal record, had for some reason not reproduced. DeGuerin got the job.

For three years DeGuerin honed his chops prosecuting Harris County criminals. As an assistant DA he was not a standout, except by virtue of his youthful appearance. “He was so pretty, with Ivy League clothes and a cute little ol’ butt,” snickers Erwin Ernst, the veteran first assistant DA during DeGuerin’s brief tenure. “We all played like we were lusting after little Dickie till he’d turn red in the face.” Still, DeGuerin worked hard, particularly so on a narcotics case that pitted him against Percy Foreman. The cocky young prosecutor strode into the courthouse that day, certain of victory, until his star witness, a police officer, was cross-examined by Foreman. By the time Foreman spat the officer back out, DeGuerin was mesmerized, even in defeat.

In 1968 Dick DeGuerin took a shot at big-bucks lawyering and hired on with Butler and Binion’s trial division. DeGuerin enjoyed some of the general litigation cases, especially “one case where a lawyer was claiming that drinking a bottle of wine bought at a grocery store insured by us had given him hemorrhoids,” he says. “I had his doctor draw the man’s hemorrhoid on a chalkboard.” He also benefitted from the tutelage of senior partner Frank Knapp, the head of the firm’s trial division. But the 27-year-old attorney had cultivated a rebel streak that chafed against the tweedy grain of Butler and Binion. DeGuerin sometimes rode a motorcycle to work and could be seen walking down the hallway in his Penney’s work shirt, briefcase in one hand, helmet in the other. He hated the insurance adjusters. In 1971, as a diversion from his regular work, DeGuerin offered to represent an attorney friend, Bob Tarrant, who had been arrested on weapons charges. Also volunteering to help was Percy Foreman. DeGuerin worked long hours on his friend’s behalf. The old man was impressed. Halfway during the trial, Foreman leaned over and whispered into the younger man’s ear, “Do you enjoy working for insurance companies?”

“No,” DeGuerin assured him. “I enjoy doing this.”

“Would you rather represent people than insurance companies?” Foreman persisted.

“I sure would.”

“Well, then,” said Foreman, “come see me.”

Later, DeGuerin showed up at Foreman’s shabby two-room office in the First National Life Building, now known as 806 Main. There the legendary Percy Foreman offered him a job. DeGuerin was shocked and told Foreman he would have to think it over, which seemed to throw the old man a bit. DeGuerin had just turned thirty. He talked to his boss, Jack Binion. Binion didn’t mince words. “If you don’t go with Percy,” he said, “then you’re a damn fool.”

DeGuerin accepted Foreman’s offer but told him, “What I’d like is for the firm to be known as Foreman and DeGuerin.” Foreman agreed without hesitation.

The old man was a workhorse who enjoyed nothing like he enjoyed his practice. He loathed physical activity of any kind and saw socializing as a waste of time. DeGuerin found this out just after starting work, when Bob Tarrant invited him to Baja California for a four-day bacchanal. Foreman was not amused and told DeGuerin he would rather the young attorney didn’t go. DeGuerin went anyway. When he returned, there was a long letter sitting on his desk. “When you impressed me during the Bob Tarrant case,” it read, “I mistook your efforts for a love of the law. Now I think it was all because you were a good friend of Bob Tarrant’s. . . . For me, practicing law is the be-all and end-all. I don’t practice law to take vacations and play golf.” The letter concluded by informing DeGuerin that his pay would be docked for the two days of work he missed.

DeGuerin knew a challenge when he saw one. “I poured myself into the next case, days and nights and weekends,” he says. After DeGuerin won, he was summoned to the old man’s office. Foreman looked up at him with a satisfied smile. Then he leaned to one side, reached deep into his front pockets—which were custom-designed to be knee length, since Foreman distrusted banks and carried his cash on his person—and pulled out a wad of dollar bills. DeGuerin counted the money he was handed. It was his two days’ worth of docked pay.

Foreman and DeGuerin was Dick DeGuerin’s firm in name only. The old man called all the shots. He expected everyone to be at work at eight-thirty on weekday mornings, ten on Saturdays. He selected and assigned all the cases. He set and collected all the fees, from which DeGuerin was paid a salary. The houses, cars, jewels, ranches, weapons, silk umbrellas, and elephants that came to the firm in collateralized fees went to Percy Foreman, who warehoused the goods and kept the accounting of them strictly to himself. At one time, Foreman owned more than forty automobiles, none of them purchased by him. At another time, he was said to be the largest private landowner in Harris County.

Foreman was not an easy man to work for. A former associate from the fifties, George Greene, Jr., remembers that in 1954, “Percy went through thirteen secretaries in a single year. He was under so much pressure, because he was seeing maybe fifty clients and trying five or six cases every day, that he had absolutely no patience for people who were slow or error-prone. He expected you to anticipate his every need.” By the time DeGuerin joined the business, Foreman, nearly seventy, was not as brisk, but he was still, as his friend Joe Jamail puts it, “a piece of shit to work for.” It was a common occurrence for him to fire his longtime secretary, Martha Allen, who would simply tune Foreman out and continue her chores.

DeGuerin was not born with a sturdy work ethic, but under Percy Foreman he developed one. He learned, during his short briefings with the impatient lawyer, “how to boil something down to its essence, which of course is a really important skill when you’re explaining something to a jury.” He learned that the business of trial law was trying cases, not pleading them, and that this often meant playing hardball with his old pals over at the DA’s office. He learned how to use the press to force answers out of the police, and how to salvage a little goodwill with the police by giving them occasional pro bono legal assistance. Above all, he learned the value of reading people: knowing when a juror remains unpersuaded, when a witness is ready to crater, when a prosecutor is bluffing, when a client is lying.

In 1972 one of the biggest Houston cases in years came into the office: the case of Lilla Paulus, accused of conspiring to murder Dr. John Hill following the bizarre death of his wife, Joan Robinson Hill. Foreman told his young associate, “It’s yours.” The trial, immortalized by Thomas Thompson’s book Blood and Money, was DeGuerin’s first case under the full unsparing glare of the media spotlight. Despite an at-times-dazzling performance, DeGuerin lost. By asking for a continuance, he gave the prosecutors a chance to work a deal with Paulus’ co-conspirator, Marcia McKittrick, and her testimony proved to be damaging. Foreman had advised DeGuerin against the continuance; but he had also insisted that DeGuerin put Paulus on the stand, and against DeGuerin’s better judgment, he did so. That proved to be the fatal error, since the prosecutors destroyed Paulus with evidence they had gotten from McKittrick.

“Well, you did your best,” Foreman told his dejected associate, “and now we’ve got to see about a reversal.” After a five-year appellate period, DeGuerin won a reversal of Paulus’ 35-year prison sentence. He never discussed Foreman’s poor judgment on the case; he simply took notice of the fact that even the old man was fallible. In 1974 Foreman himself stood trial on a charge of driving while intoxicated. Every high-profile lawyer in the nation offered his pro bono services. Foreman selected Dick DeGuerin. It was as high an honor as Percy Foreman could possibly bestow. Today DeGuerin discusses the case with fresh zeal. ‘“We had this great defense,” he enthuses. “See, Percy had been diabetic since 1954. He was probably as drunk as he could be, but the fact is, when you’re having a diabetic attack, you act drunk—even to the extent of giving off an odor that’s just like alcohol. So it was a five-day trial. I built it up this way: First I brought on the police officer and the kids who were eyewitnesses, and I got them all to admit that they’d never seen a diabetic attack and therefore wouldn’t be able to tell it from drunkenness. Then I bring up Percy’s doctor, who testifies that Percy’s diabetic. And then I bring up the Harris County medical examiner, Dr. Jachimczyk. And he testified that not only did he know Percy personally and knew he had diabetes, but that several times in the past, Houston police officers had mistaken diabetic attacks for being alcohol-related and threw them in jail, where they died! Perfect testimony!

“And that’s the setting for when Percy took the stand.”

The legendary lawyer was everything he had always instructed his clients not to be. He sat on the witness stand, his arms folded tightly against his massive chest, glowering. To the prosecutor, a nice fellow named Mike Maguire, Foreman snarled, “I hear they call you Young Cassius.” He volunteered that he was not only not drunk that particular day, but in fact, “I’ve never been drunk a day in my life.” He was a study in arrogance. The jury found him guilty and the judge sentenced him to probation.

DeGuerin and Foreman walked back to the car in silence. The young lawyer knew the old man had dug his own grave, but DeGuerin had developed his own perfectionist streak under Foreman’s tutelage and now tormented himself thinking of ways he could have salvaged a victory. “Look, I’m sorry,” he began, but Foreman cut him off. “Don’t worry about it,” grunted the old man, and they drove back to the office together and did not discuss the case again.

“Sibling rivalry is one of the most recognized normal negative traits in our society,” says 49-year-old Michael DeGeurin as he sits in the chair that was once the property of his mentor. “Dick and I are unusual siblings in that we’re each other’s best friends. So in thinking about whether or not to work in my brother’s practice, I was only apprehensive in this sense: ‘Will I measure up?’ ”

The physical similarities between the brothers are just enough to accent the differences. “Mike isn’t as precious as Dickie,” says Erwin Ernst, by way of understatement: The younger brother is short, he is gravelly voiced from his cigarette habit, and he wears suits that are wrinkled and somewhat ill-fitting. His office has the orderly appearance of a broom closet. Accordion files dominate the floor and yellow Post-it notes cover the edges of his desk, which is heaped with pleadings and notepads. Where Dick DeGuerin has taken the Percy Foreman style and added a few coats of gloss, Mike DeGeurin has stripped the style down to its most primitive hide. Here at Foreman’s firm, the work gets done just as Percy would have it, but no cameras, please. As in the old days, clients sit for hours in the waiting room, attended to by Martha Allen, Foreman’s longtime secretary. Mike DeGeurin never charges an initial consultation fee, and he always makes a point of “leaving people who come into our office better off than when they came in, whether we represent them or not,” he says. That’s the way Percy Foreman did things.

On the wall of the waiting room, the sign used to read “Foreman & DeGuerin.” Now it says “Foreman, DeGeurin & Nugent” (Paul Nugent joined the firm in 1985), and below the words hangs a framed black and white oil painting of the old man seated atop a desk, and behind him a quiet and respectful presence, Mike DeGeurin. The family name on the firm logo is now spelled Mike’s way. It is he who stayed behind.

“Mike is more of a diplomat than I am,” says Dick DeGuerin. “He’d rather get people to agree.” It is Mike, the conciliating little brother, who is best loved among the state’s judges, while it is Dick who has the reputation of a man who doesn’t care who he offends. It is the difficult older brother who felt compelled to change the spelling of his surname. It is Mike who was praised by their father for his quiet loyalty: “I know of no one who can keep a secret better than you,” he told him. Houston attorney David Berg calls Mike DeGeurin “the most underrated lawyer in Harris County”—a tag that could not possibly apply to the older brother, for all his deft manipulation of the news media. When Dick represented Mike in a landmark withholding-of-privileged-information case in 1990, the older brother insisted that they ram the case down the U.S. attorneys’ throats. Mike reluctantly agreed, but he was adamant that his name be kept out of the pleadings and was more than happy to leave most of the interviews to Dick.

All the same, Mike DeGeurin possesses the little brother’s determination. After finishing law school—far surpassing Dick in his grades—he clerked for a state judge and then a federal judge, then went searching for work in Houston. Dick offered to get him a job at the DA’s office; with his connections, it would be a cinch. Mike DeGeurin refused. “I can take the most awful person and after thirty minutes with him, come up with more good in him than there is bad,” he says. “I just couldn’t see myself pointing my finger at that person in trial and telling the jury to send that person away. The idea of developing my skills and getting practice by prosecuting some poor soul didn’t appeal to me.”

DeGeurin hired on at the public defender’s office, where his performance was closely monitored by Foreman. In 1976 the old man said he wanted to hire Mike, starting next week. “I can’t do it,” DeGeurin told him. “I’ve got five or six cases scheduled for trial. These people are counting on me.” Foreman grumbled, “Son, you’re building a hell of a foundation as a lawyer. But someday you need to get off the first floor.” Still, he appreciated the young man’s priorities. A few months later, the old man offered the job again and Mike DeGeurin snatched it up.

By 1982 Foreman and DeGuerin did more criminal law business than any firm in the state. In addition to Mike DeGeurin, the firm had added Charles Szekely and Lewis Dickson. Foreman was now eighty and seldom made appearances in court. “He quit trying cases,” recalls Ernst, “and let the boys try ’em.” Rumors drifted through the courthouse that the old man had lost it. The boys knew better. When Foreman told Dickson to get a bid from ABC Bonding Company, Dickson thought, “Well, bless his heart, his memory’s failing. We always do business with ABD Bonding.” Dickson took it upon himself to call ABD. When Foreman got wind of this, he charged into the young attorney’s office and hollered through clenched teeth, “I told you ABC, not ABD! A-B-C-D-E-F-G . . .” He proceeded to recite, at top volume, the entire alphabet in Dickson’s sheepish face.

For years, Dick DeGuerin had stewed quietly while his peers, less talented than he, were raking in the dough. Foreman always paid him well, but not nearly as well as DeGuerin’s talents were padding the pockets of the old man. “Unless you make me ten times what I pay you,” DeGuerin was told, “you’re not worth it to me.” DeGuerin was well aware that the big firms were content with profit margins of around 20 percent. “I never knew what the bottom line was—Percy kept that to himself,” he says today. “But I know that I made Percy millions and millions of dollars.”

The stylistic differences between them bespoke their separate generations. Foreman did his afternoon work at the Old Capitol Club, where the waiters brought him a private phone and a succession of scotch and sodas. DeGuerin didn’t care much for the joint: It was filled with geezers who bragged about how they had never lost a case. DeGuerin spent his early mornings jogging, which Foreman found unfathomable. Worse, the jogging routine often caused DeGuerin to be late to the 8:30 meeting, an outrageous flouting of office procedure Dick DeGuerin committed repeatedly, as if hell-bent on getting the old man’s goat. Then there were the first-class airplane tickets and hotel suites DeGuerin charged to the firm. It was the young attorney’s way of asserting his right to the high life. But Foreman, who fought his way out of the Depression, was apoplectic over this abuse of office funds. He promptly circulated a memo banning all luxury purchases and forced each attorney to initial it.

But it wasn’t just the kid’s tardiness and fiscal irresponsibility that rankled the old man. The fact was that Dick DeGuerin had now made a name for himself. At first Foreman encouraged this, though with a certain ambivalence. As early as 1973 he had hired another associate, DeGuerin says, “just to put me in my place after I’d had a long string of successes and he was worried I might leave.” Instead it was the new fellow who left. But by 1980 clients were coming directly to Foreman’s younger associate; now reporters were asking to speak to Dick DeGuerin. Foreman began to make snide comments whenever he overheard DeGuerin returning a reporter’s call. It was a little hypocritical of him, considering that Foreman often said, “Hell, I know the press made me.” But he was still Percy Foreman. Nobody rubbed anything in his face.

Dick DeGuerin’s apprenticeship made a great lawyer out of a good one. Now it was time to move on. He discussed the decision to leave with his brother, Szekely, and Dickson. The latter two said they would jump ship with DeGuerin. In June 1982, DeGuerin walked into Foreman’s office. “I’ve enjoyed every minute of this, but I need to make a name for myself,” he told the old man. “I don’t want to be one of those kinds of lawyers who tries to take over the older lawyer’s business. So I need to start my own deal.”

Foreman took it well, though his eyes were teary. They shook hands and agreed that DeGuerin would stick with the firm through September, when all of the cases he handled would be cleared. What they failed to discuss was what to do with the new cases that would come DeGuerin’s way in the meantime. On the morning of Friday, July 2, Foreman poked his head into DeGuerin’s office. “These new cases that have been coming into the office that you’re taking,” he said. “Do you intend to keep the fees?”

“Yes, I do,” said DeGuerin.

Foreman exploded. “By God, as long as you are working in my office, the money that comes in here is mine!” he roared. “I want you to turn over the money that they’re going to pay you, or I want you out of here!”

DeGuerin, stubborn to the end, said, “Then I’ll leave.”

By the lunch hour, Percy Foreman had locked Dick DeGuerin out of the building. Later, Charles Szekely informed Foreman that he was leaving as well. When it came Dickson’s turn, the old man was despondent. “Why not stay here with me and see how Dick does?” he asked and offered to quadruple Dickson’s salary. Dickson looked his idol in the face and turned him down.

“I’m sure it was devastating to him,” Dick DeGuerin says today in that even, mentholated voice of his that betrays scarcely a drop of whatever emotions circulate within. It is the belief of Mike DeGeurin, the mediator, that Percy Foreman staged the whole disagreement himself purely as a means of kicking Dick DeGuerin out of the nest. But that scenario does not square with the behavior of Foreman, who refused to speak to DeGuerin for a long time thereafter.

Dick DeGuerin, prodigal son, lawyer without an office, showed up at the building occupied by his friend David Berg. Berg let DeGuerin encamp in his conference room. “I stayed there for two months,” he says, “and in David Berg’s conference room I made more money than I had made in the past three years with Percy. Literally.”

The rise of DeGuerin surprised no one. He was slick and camera-ready but also a tenacious streetfighter. In the 1983 book The Best Lawyers in America, he was named by his colleagues as one of the nation’s best criminal defense attorneys. His fame culminated in 1986 with the successful defense of Hurley Fontenot, an East Texas principal accused of murdering a football coach; the acquittal of three New York Mets baseball players after a barroom brawl with a few Houston police officers; and the release of immigration lawyer Edward Gillett, who was found not guilty on more than eighty counts of immigration fraud.

Meanwhile, Mike DeGeurin tended to Percy Foreman’s business. It was just the two of them now, and the heavy workload required Foreman to return to the courtroom. It was obvious the old man lacked the fortitude of his earlier days. He spent much of the day napping on his couch or issuing blistering memos to the fire marshal and charity solicitors. It was never necessary to vent his ire on the younger brother. As Lewis Dickson says, “He yelled at Dick knowing he would be ignored and yelled at me knowing he would be heeded. Mike he simply shamed into following his will.”

The two had become extremely close, even more so after DeGeurin’s father died in 1982. One day the old man said to the younger brother, “There’s a reason people say life begins at forty. It takes forty years of life experiences to know who you are, what your purpose is, how you fit in. But if you can find someone who’s much older than you who you can trust and who will hand you distilled knowledge so that you don’t have to go through what they did—well, then I will be that person for you.”

Overwhelmed, Mike DeGeurin said yes. “And from then on until his death,” he says, “every day he would hit me with at least one new piece of distilled knowledge. Yes. What we had was special.”

In 1987 Mike DeGeurin won a rehearing for Clarence Brandley, a Conroe janitor who spent seven years on death row for the murder of a high school cheerleader. DeGeurin’s dedication to the case and his interrogation of the law enforcement officials who had collared Brandley were breathtaking; ultimately, Brandley was freed. Now Mike, like his brother, was ascending. That same year, Percy Foreman received an award for World’s Best Lawyer. As he stood onstage, eyeing the gigantic plaque he held with both hands, Foreman seemed not to know where he was. A sick murmur arose from the young lawyers in attendance. The old man had clocked out.

At last, Percy Foreman said slowly, “You know, I feel like the cowboy on the corner with a saddle in his hands. I can’t remember whether I lost my horse or found a saddle.”

In the summer of 1988, at the age of 86, the great man’s heart failed. He was rushed into intensive care and was there for several days. Mike DeGeurin showed up at Methodist Hospital with news he hoped would cheer up the old man. “Percy, I’ve got a gift for you,” he said. “I’ve got a client in Cincinnati who’s charged with murder, and he says that he’ll give me his ranch in California if I represent him. So there’s another ranch for you.”

At that moment a doctor poked his head in the door. Through the tubes and the machines, Foreman managed to bellow, “Get out of here, goddammit! We are consulting!”

The doctor fled, and Percy Foreman summoned his last bit of legal advice: “You’d better get photographs of the ranch. What they call a ranch in California is not what we call a ranch in Texas.”

The property, as it turned out, was a mere three acres with a trailer. Had it been a thousand, the old man would not have been around to enjoy it. He died soon thereafter. At the funeral on August 29, both brothers gave speeches. Dick spoke in his clear, dispassionate voice. “Finally I can tell you how I feel,” he said, daring to address his wrathful father directly, “without fear of interruption.” Mike gave his speech in tears, sobbing all the way through it, but anyone who knew the younger DeGeurin knew that he would finish the speech, and he did.

The Harris County Courthouse closed down that morning. It was what you did when a giant said good-bye.

The courthouse is now filled with a new generation of lawyers, and the idle conversation among them suggests a certain revisionism. Percy Foreman, to hear some of them tell it, was nothing but a grandstander and a drunk, perhaps even a crooked lawyer who rigged juries. As to the latter charge, there is only hearsay. But wiser souls in the courthouse acknowledge the pervasiveness of Foreman’s influence. “I think Houston has the best criminal attorneys in the nation, on both sides,” says 228th state district judge Ted Poe. “And I think Percy Foreman is one of the chief reasons for that. He raised the standard not only for defense attorneys but for DAs, who knew they’d have to get good if they had any hope of beating Percy.”

Erwin Ernst agrees but sees where most of the Foreman legacy is concentrated. “He taught those two boys all of their pizzazz, and today you hear them use a Percy quote for every situation,” he says. “Hell, he’s still guiding them.”

Of course, Dick DeGuerin runs his business his way. Lewis Dickson is a partner and draws a share of the business as well as a salary. DeGuerin believes Foreman at times went overboard with the number of clients he took on. “I don’t want a law factory here,” he says. As it is, DeGuerin has pushed aside all other cases while concentrating on Kay Bailey Hutchison’s defense. “We could use another hand around here,” he concedes, “but it would have to be someone I can trust. Actually, I’ve always had a dream that Mike and I would get back together someday. He and I have implicit trust in each other, and Paul Nugent’s a fine attorney. But you know Mike. He’s the little brother. He doesn’t want to be under his big brother’s wing.”

Mike DeGeurin smiles warily at the topic. “I enjoy making decisions without having to argue with my brother about it,” he says. And there are other things at stake. When Percy Foreman died, he willed Mike his business—and he willed him his name. The actual name, “Percy Foreman.” How could Mike DeGeurin desert all that? This was his firm now, though always the old man’s. Percy would have had something to say on the subject, something about spiritual destiny. Then again, the two of them never got a chance to talk about religion.

The younger brother looks up from his mood and peers out the doorway. “Mary,” he calls out to a secretary. “Mary, there’s a client out there in the waiting room.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston