This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On most days of the year, you might drive right through Huejotzingo without stopping: It seems to be just another sleepy town on the old highway from Mexico City to Puebla. All you would notice would be the giant eucalyptus trees that line the road, the vast apple orchards that fill the countryside, the twin volcanoes—Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl—that float against the blue sky.

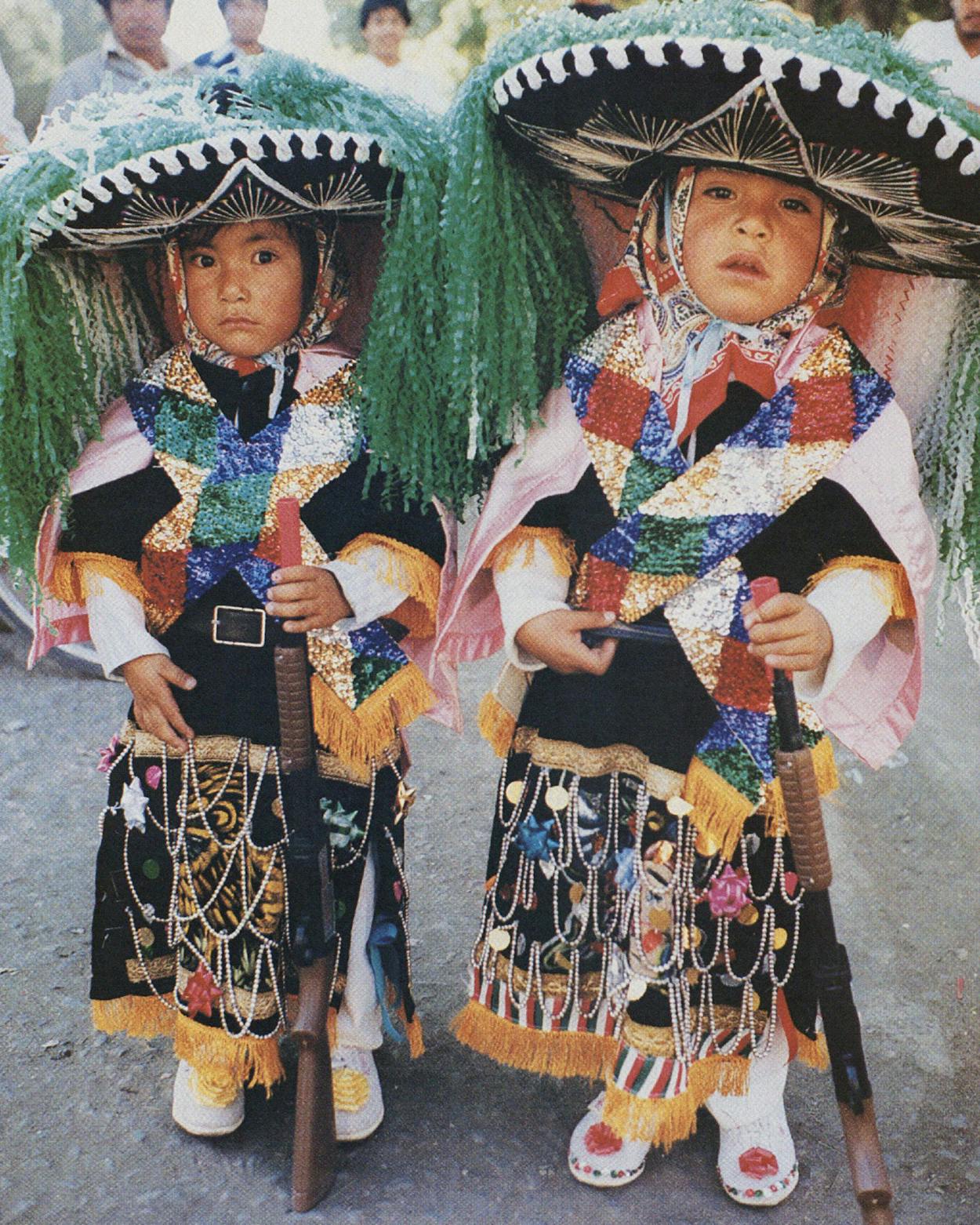

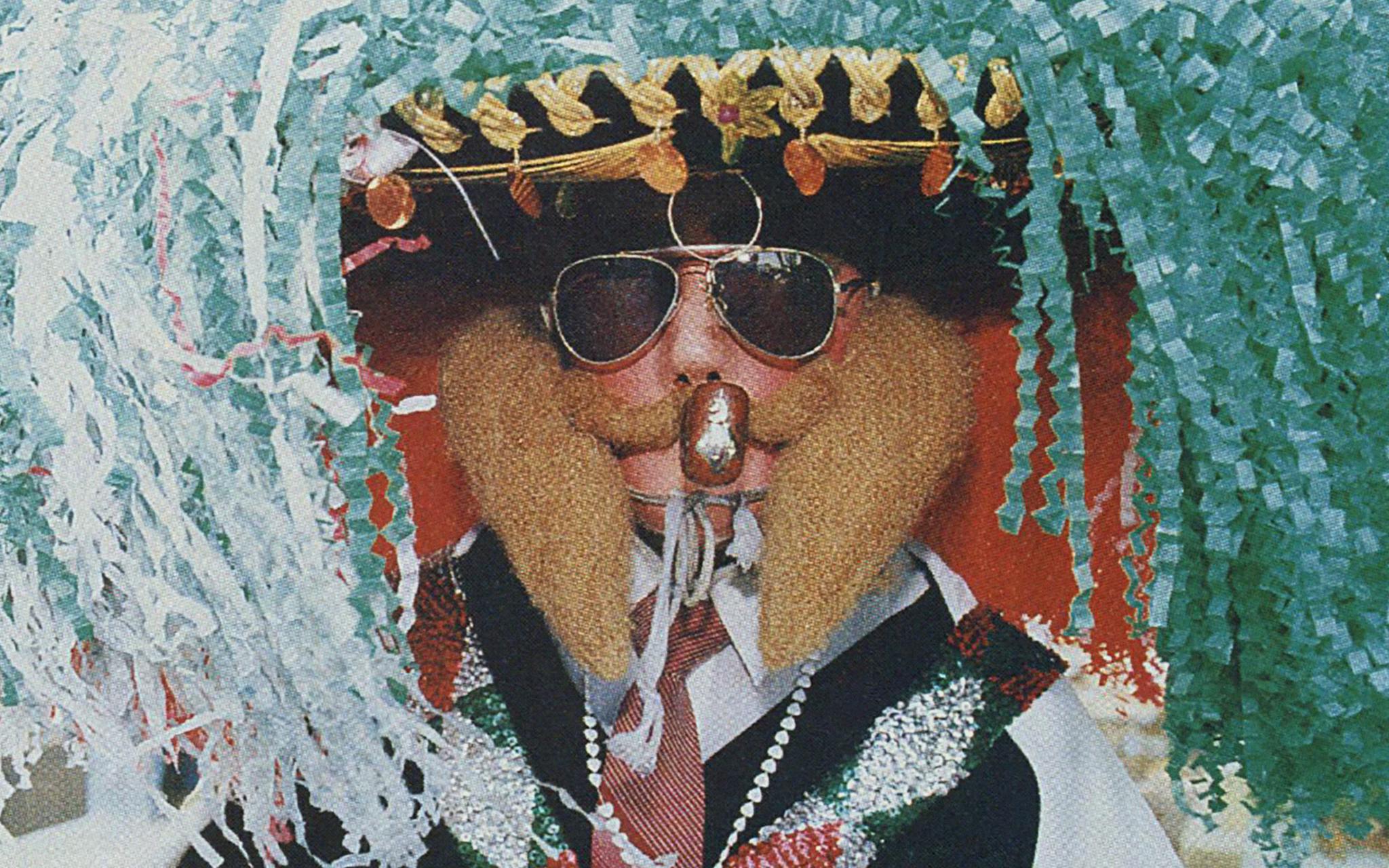

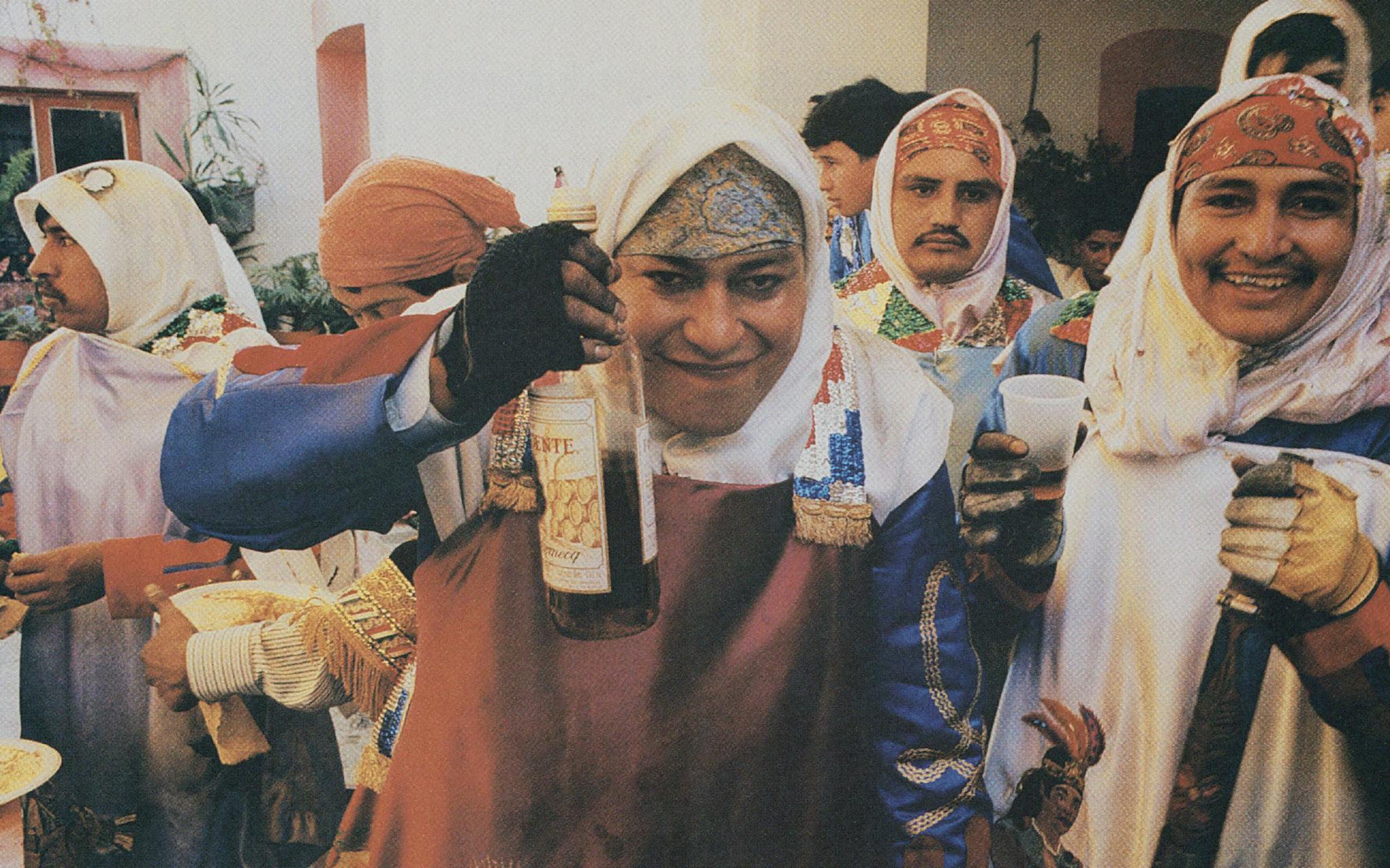

Yet on the three days before Lent (February 13 through 15 this year), Huejotzingo is a place you would never forget, for it is the site of one of the most chaotic carnavals in the western hemisphere. Early in the morning on the first day, gunshots can be heard all across town. By dawn, people dressed in outlandish garb—as Indians, French soldiers, Turks—gather and dance to the music of local bands. By mid-morning, the streets have become a series of mock battlefields shrouded in gun smoke, as battalions of soldiers fire at each other with muskets. Amid all this, a beautiful girl appears on a balcony and is swept away by a noble bandit, who himself is pursued by lawmen on horseback. French and Mexican soldiers fire at the lawmen, cheering the abductor and his prize. At the same time, an ancient baptism and wedding are recreated in the zócalo.

Then the whole thing is repeated, again and again, until nightfall on the third day. It is Carnaval as it can happen only in Mexico: historical and whimsical, sacred and profane, full of fireworks and firewater, wild and crazy and wonderful.

Geoff Winningham is a professor of art at Rice University in Houston.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Photo Essay

- Mexico

- Festivals