This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There is something special about places at the end of the line. People who come to such places have two choices. One is to turn around and go back; the other is to stay and take what comes along. In time, such a place accumulates a disproportionate number of loners, drifters, seekers, romantics, and fugitives from normal, boring, regulated life. Their philosophy generally includes a desire to be left alone and a willingness to leave others alone. Therefore, the community tends to be more tolerant and relaxed than most.

—Joseph J. Thorndike, The Coast

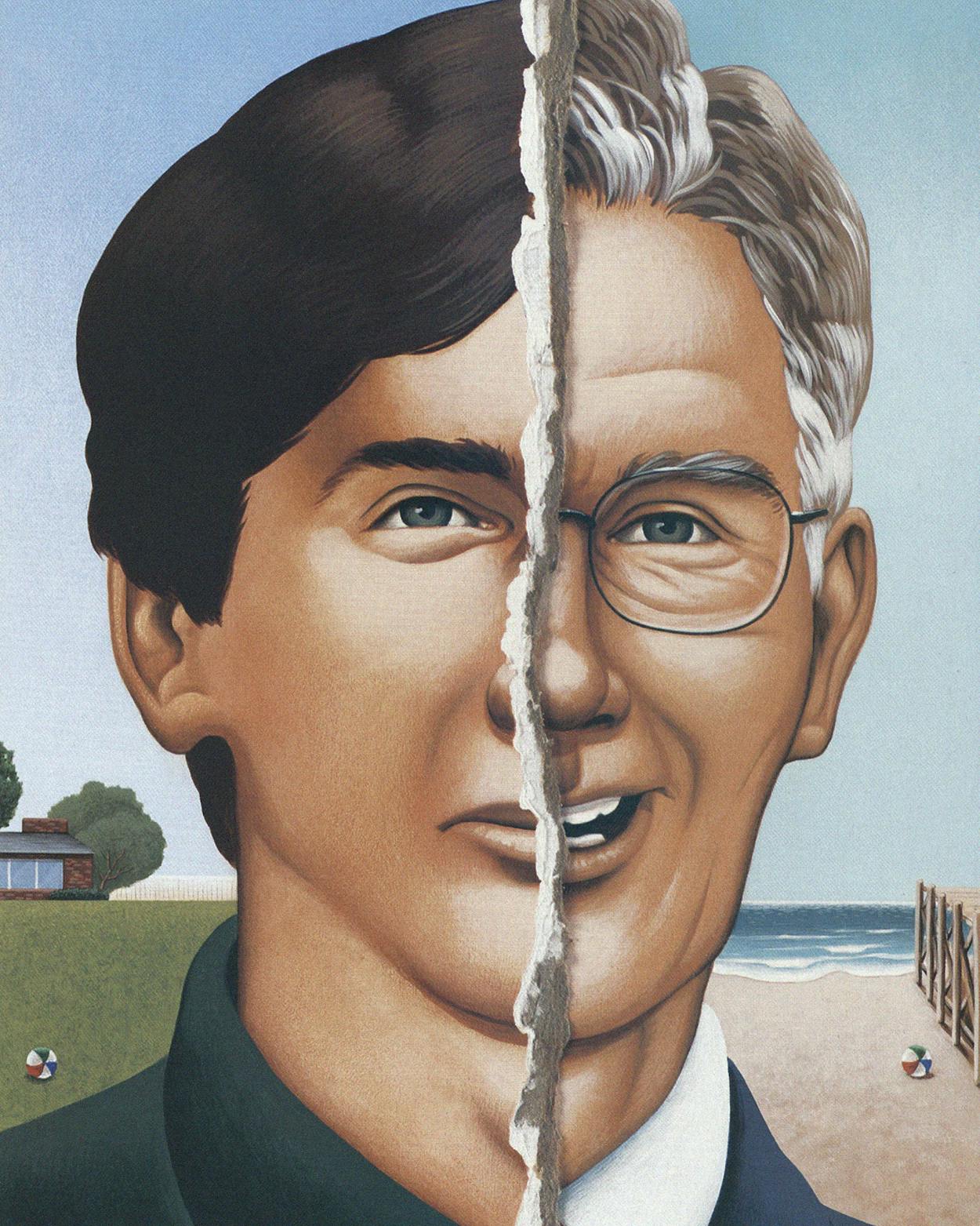

The place at the end of the line for Patrick Hennessy Welsh was a sandbar in the Gulf of Mexico. He was not a loner, not at all, but he was definitely a seeker and a fugitive when he arrived in Galveston sometime in the spring of 1983. The son of a prominent radiologist in Lancaster, Ohio, he was searching for a new life and a new identity, and he was fleeing from something far worse than a normal, boring, regulated life—the shame of a conviction and a probated sentence three years earlier for embezzling $27,000 from Ohio State University. Pat Welsh had come to the right place. Battered by storms and by fate for most of this century, Galveston was enjoying a long-awaited renaissance. A newcomer to town didn’t stand out the way he would have a few years earlier. The Strand historic district was thriving, Houstonians were sprucing up old Victorians, and an upstart tabloid called InBetween was writing about the Moodys, the new arts scene, the gossip, and all the other things that never appeared in the Galveston Daily News. The crowd of artists, writers, and town characters who gathered every afternoon to drink beer outdoors in front of the Old Strand Emporium called Galveston “the cul-de-sac of Interstate 45,” and they referred to themselves as IBC, an acronym for Islander by Choice—as contrasted with BOI, or Born on the Island, Galveston’s invisible passport to acceptance and privilege. If you are BOI, you can get medicine without a prescription or cash a check from an out-of-town bank with no questions asked or get a crucial document from the courthouse after working hours. I know, because I am BOI, and I have done all of the above, even though I return only for a few weekends a year. If you are not BOI, no one in Galveston cares what you were before you came there, which was just perfect for Pat Welsh. Or, as he started to call himself soon after he arrived, Tim Kingsbury.

For the next fifteen years, until late January of this year, Pat Welsh lived the dream of everyone who has made the big mistake or the wrong choice: What if I just chucked it in and started over? He made a name for himself—in every sense of the phrase—in Galveston. Tim Kingsbury became the town’s indispensable citizen, a volunteer for every good cause, a friend and confidant of its leading citizens. He went from writing press releases for the Galveston Historical Foundation to being elected its president, from freelancing occasionally for InBetween to playing tennis regularly with the publisher of the Daily News. Organizations from the Boy Scouts to the Women’s Crisis Center sought him out to sit on their boards. He managed the campaign of a successful mayoral candidate; he became the general manager of the town’s only radio station; for a time he was even the local restaurant reviewer for Texas Monthly. The goings-on-about-town columnist for the Daily News invariably referred to him as “the amazing Tim Kingsbury,” and it was hard to know which was more amazing—his compilation of good deeds or that in Galveston an outsider had become an insider.

But the story of Tim Kingsbury was to get even more amazing. On January 30, while he was working on a car in his driveway, two sheriff’s deputies walked up and announced that they had a warrant from Ohio for the arrest of Patrick Hennessy Welsh. In the days that followed, the mask was stripped from Tim Kingsbury to reveal the past that he had labored so long to conceal. The privileged childhood. The failed ambition to follow his father into medicine. The embezzlement. The wife and two young sons he left behind. The two suicide letters he mailed to his wife after he vanished one winter night. Her struggle to overcome the financial and emotional ruin he left behind. The declaration that he was legally dead, which allowed her to qualify for life insurance and social security death benefits. The revelation that his secret identity, along with forged documents, had been discovered by Galveston law enforcement officials in 1996. Their decision to let him quietly plead guilty, accept probation, and go on being Tim Kingsbury. The discovery by Elizabeth Welsh that her husband was still alive and how she tracked him down at last. The human drama of the tale made it national news and drew the attention CBS’ 48 Hours, which is filming a documentary that will appear later this year.

Today Patrick Welsh sits in an Ohio jail cell, awaiting trial on felony charges of abandoning his family and inducing the payment of fraudulent death benefits. Back in Galveston, though, his alter ego, Tim Kingsbury, continues to fascinate and absorb a community—not the charming, historic Galveston that the tourists see, but the eccentric town of which I am so fond, known only to people who have lived there a very long time. For Galveston has been conned again, done wrong by one of its leading citizens, which is an old, old story on the Island. Part of Galveston lore is the belief that the Island’s ruling families—the Moodys, the Kempners, and the Sealys—long ago stifled rather than stimulated the town’s economy; another prominent clan, the Maceos, convinced Galveston that its only salvation lay in promoting and protecting illegal but wide-open gambling and prostitution. In the eighties a sure-enough con man named J. R. McConnell came to town, throwing money around and paying eye-popping prices for property. After his pyramid fraud scheme was exposed, he committed suicide in the county jail. People still talk about him today; Galveston loves a good con.

But Galveston doesn’t know what to make of Tim Kingsbury. Was he a con or was he for real? This is the subject of much argument, because there is a financial stake in the answer as well as an emotional one. As a volunteer at the annual Dickens on the Strand festival, he may have handled large sums of cash, and at the railroad museum, where he was the executive director for nine years, he had the opportunity to do the same. When the money was in his hands and no one was looking, was he Tim Kingsbury, civic do-gooder, or Patrick Welsh, embezzler?

As much as the Tim Kingsbury case is quintessentially a Galveston story, then, the issues that it poses are universal: Can someone really change? Do good deeds wipe out bad ones? Is it possible to start over again and redeem one’s life? Texas in particular has always had a romantic view of the notion that a man could reinvent himself here. Even before independence from Mexico, this was a society shaped by people who were running away—some, like Sam Houston, from bad marriages; some, like William Barret Travis, from bad deeds; some, too many to name, from bad debts. To flee to Texas was so common that the departed often just scrawled a cryptic note to family, lawmen, and creditors on the doors of their abandoned homes: “GTT,” which stood for “Gone to Texas.” It meant, “Don’t bother to look, because you won’t find me.” What this celebrated history omits is that a person can run away from his mistakes, but the mistakes do not cease to exist. They continue to affect the people who are LIO—Left in Ohio. Pat Welsh left his wife with a $400-a-month job, a $550-a-month mortgage, and fifteen years of guilt for not preventing his suicide, and he cleaned out his ten-year-old son’s piggy bank before he disappeared. Did Tim Kingsbury do enough good deeds to wipe out Pat Welsh’s bad ones? There was only one way for me to find out—to go back to Galveston and talk to my old friends, who, as it happened, had been Tim’s friends, and try to find out how Patrick Hennessy Welsh turned into Timothy Michael Kingsbury.

It is after supper as I write this, and I am thinking that the man I have known for ten years is in jail tonight. I hurt for him and others in Galveston who love him . . . I don’t know about this guy from Ohio, or what he did or didn’t do. But I know Tim Kingsbury is a man of real value.

—Dolph Tillotson, column in the Galveston Daily News, January 31

I had met Tim Kingsbury, of course. if you spent any time on the Strand or went to any civic events, you were bound to run into him, and the first thing you would notice is that he knew everybody. Yet he didn’t have the kind of charisma that would make him stand out in a crowd. He was a couple of inches under six feet tall, slim and youthful-looking at around 150 pounds, with soft green eyes behind his spectacles and thick, wavy brown hair that was always in need of cutting. He was soft-spoken and courtly toward women and had impeccable manners, something that can take you a long way in Galveston. “Women were attracted by his goodness,” the wife of one of Tim’s best friends told me. Men were less overwhelmed; some regarded him pragmatically as an asset to Galveston but personally as a little, well, unmanly. A lawyer who served on a board with him told me with a touch of disdain, “Tim was a nonprofit kind of guy.” Patrick Welsh had had appetites: for money and for liquor, which he consumed in occasional binges. Tim Kingsbury had none. He evidenced no interest in money; as for liquor, he drank an occasional glass of wine or a margarita, but never to excess. Every Sunday for four years he played tennis against the same doctor—and never won once or seemed to care that he didn’t.

The philanthropic community is divided into those who want the credit and those who do the work. What endeared Tim Kingsbury to Galveston is that he had the talent to be in the former category but the grace to understand that he was more useful in the latter. He was the person everyone with an idea wanted to talk to. He had follow-though, I kept hearing; he knew exactly whom to call on to get something done. Over a game of tennis one afternoon, he told Daily News publisher Dolph Tillotson about the nascent proposal to guarantee every local high school graduate a tuition-free education at Galveston College. The paper gave a huge grant to the endowment fund.

“Galveston has a small talent pool,” Shrub Kempner, the fourth-generation leader of his influential family, told me. “You can always find someone who wants to be president of an organization, but it’s hard to find people like Tim, who are willing to do the work.”

Galveston, Tim Kingsbury had proved, wasn’t such a hard town to crack after all. Her heart can’t be bought with money, but she is a sucker for someone who appreciates her charms and offers to serve her. That he was a man without a past only added to his mystique. The story he told, whenever someone asked about his background, was that he had lived in Ohio, made a mistake in life, and decided to start over. He got on a bus and rode until the money ran out. That was all. “He never talked about his past,” said a woman who, along with her husband, was one of Tim Kingsbury’s closest friends. “It was especially noticeable around holidays, when everybody was talking about their families. You just knew not to ask him.” But his past didn’t really matter, old-line Galvestonians told one another. What did matter was that their town had brought out the best in him, that he needed Galveston as badly as Galveston needed him. “He volunteered in the schools to teach reading to underprivileged children,” one of his best friends told me. “You don’t get a plaque for that.”

Galveston’s history is in your future.

—slogan from the Galveston Historical Foundation Web site

What Galveston didn’t know was that Tim Kingsbury was still Patrick Welsh when he got off that bus in 1983. He picked out his false identity, choosing a familiar but not too prominent Galveston name—a Kingsbury had taught in high school while I was there—that gave him a patina of BOI identity. He found an unfurnished room in the oldest part of town and a job in a sandwich shop. At night he bedded down in a sleeping bag. I could not find a single BOI who knew him during those first months on the Island.

The moment that changed his fortunes occurred in October of his first year in Galveston. He spotted an ad in the Daily News seeking a part-time publicist for the Galveston Historical Foundation, whose full-time publicist, Laura Nite (her current name) was pregnant and due in January. The job was right up his alley: Patrick Welsh had written press releases at Ohio State. When he applied, Nite had some misgivings about recommending him (and she would have more misgivings later). “He said he was a medical student,” she recalled, “and the medical students I knew spent all of their time studying. But he said he could handle it, and naturally he wrote a perfect press release.”

The Galveston Historical Foundation proved to be Tim Kingsbury’s entrée to BOI Galveston. The foundation was the sole interface between BOIs and IBCs. Its large cadre of volunteers came from both groups. The Moodys and the Kempners helped underwrite it. When Laura Nite left to have her baby, Tim Kingsbury became the foundation’s full-time publicist. If there was a single position in town in which it was possible to know just about everybody worth knowing, he now held it.

The foundation job proved to be crucial to Tim Kingsbury in another way. There he met a fellow employee named Ann Anderson, who was not only well liked in town but also respected for maintaining a quiet dignity after many years of being unlucky at love. Her Galveston pedigree could not have been better: Her grandfather, a physician, had also been the owner of the old Tremont Hotel, in its heyday a place where presidents had slept. Tim and Ann became what they called “life partners.” He moved into her home, a large one-story structure that was raised on stilts because it was situated right on the edge of Offatts Bayou. “Tim ‘married’ well,” an old friend told me.

I had known Ann years ago, when her older brother, Vandy, and I were friends in high school. I saw her again in Ohio at a hearing on a motion to reduce Tim’s bail (it was denied) and asked her to tell me about their life together. She shook her head sadly and gave me an answer that was pure Galveston in its baroqueness: “You’d understand if it were your baby sister.” Tim wasn’t talking either, not until after his trial. But I did get to talk to Vandy, whose career I have followed—he was a newscaster and part-owner of KGBC, the radio station where Tim recently worked as general manager, and over the years, the president of the school board, Rotary, the chamber of commerce, the century-and-a-half-old Artillery Club, you name it.

“What torture he must have been under all those years,” Vandy told me. “The more public his life became, the bigger the risk was of being found out.” And then, once more, I heard about the goodness of Tim Kingsbury. “He was never out for himself,” said Vandy. “He never accumulated anything except goodwill.”

Knowing InBetween was running its annual feature on Galveston’s “Most Eligible” singles and knowing they know I’m eligible, I picked up several extra copies of the last issue to send home to Mom and a few old girlfriends. Can you imagine my surprise to find out I was not mentioned therein?

—Tim Kingsbury, writing about himself in InBetween, January 1984

Vandy had described Tim Kingsbury as BOIs knew him. But IBCs knew a different Tim Kingsbury during his early days in Galveston—a waitress-chasing carouser, a self-promoter, and a not-so-skillful liar. I came across this person, who had more in common with Patrick Welsh than with the Tim Kingsbury Galveston would come to know, while going through back issues of InBetween. He had written at least ten articles, including the one quoted above that so cavalierly referred to his mother, who was then grieving for her missing son. Most were written in the first person and featured himself doing new and exciting things. In this one, he wrote as a novice training for a marathon—not mentioning that, as Patrick Welsh, he had run in organized distance races. Later he wrote about learning to sail and to scuba dive. One can deduce that he was something of a town character, because the headlines all referred to him by his first name: “Tim Takes a Hike” . . . “Tim Tosses His Cookies” . . . “Tim Takes a Dive.” The style is hardly the work of a person laboring under the torture of discovery. In one article, he wrote, “I’ve been thinking about expanding these ‘Tim Takes a Hike’ stories into a series of experimental pieces under the general heading of ‘Tim Leads a Full, Happy, and Productive Life.’ Topics that come to mind include . . . the action-packed ‘Tim Picks Up Chicks at the Glitterdome’ or the romantic ‘Tim Takes a Wife,’ though that last one may require more of a commitment than the marathon articles.” But Tim already had a wife.

What I read changed my opinion of Tim Kingsbury. Maybe he had been Patrick Welsh all the time. The InBetween articles are the work of someone who craves recognition, and recognition had been important to Patrick Welsh. As a Welsh of Lancaster, it was his birthright. When he didn’t get the recognition he thought he deserved as assistant director of development at Ohio State—a promotion and a raise—he embezzled. Found out, he lost his chance to be somebody important in his home town. He told the Galveston sheriff’s officers who arrested him that he left Ohio because he couldn’t stand living in a town where everybody knew his business. In Galveston he could be somebody again; it was just a matter of finding his niche. One of the first things he told Elizabeth Welsh when they met in jail after his arrest was that he wanted to go back to Galveston. “I’ve worked very hard to become Tim Kingsbury,” he said.

But a few people knew who he really was. Laura Nite, who had had misgivings about recommending Tim Kingsbury for the job at the Galveston Historical Foundation, continued to have doubts about him after he was hired. He had said he was 27, but she heard from a friend that one night he drank a little too much and started reminiscing about Vietnam. “How old were you, twelve?” somebody at the table asked, and that may have been when Tim Kingsbury decided that liquor and his secret identity didn’t mix. The waitress he was dating, according to Nite, was suspicious enough that one time, when he was taking a shower in her apartment, she checked his wallet and found Patrick Welsh’s ID and his true age of 35. Enough didn’t add up that Nite called the University of Texas Medical Branch and asked if Tim Kingsbury was registered. He wasn’t. This time she confronted him. “You must have misunderstood,” he said. “I said I was thinking about going to medical school.” A hostile look in his eyes persuaded Nite not to take the matter further with him. But she continued to make quiet inquiries into his background.

Other people knew about Patrick Welsh. Renee Kealey, whose uncle grew up on the same block as I did, was a drive-in teller at University National Bank in the fall of 1983. It turns out that Pat Welsh didn’t get off the bus broke after all—or, if he did, he didn’t stay broke for long. “I remembered him because he had a large account, around $20,000,” she told me by phone from Hong Kong, where she now lives. “He only made withdrawals. The reason I remember it is that I was watching Channel 12 one night, and I saw Patrick Welsh’s picture on the screen, something about the Galveston Historical Foundation. Then they said his name was Tim Kingsbury.”

Little by little, the Patrick Welsh side of Tim Kingsbury’s personality retreated into hiding, to be replaced by the side that Galveston would embrace. He stayed at the foundation until 1986, when he was recruited by the railroad museum as executive director. But when board members wanted him to undertake a national fundraising campaign, he balked. It was the only time anyone had ever seen him agitated. In retrospect, one board member told me, the resistance may have been because of his fear of being found out; someone might have recognized him from his Ohio State days. Perhaps it was coincidence, but soon afterward he left the railroad museum for the safety of KGBC.

Except that KGBC wasn’t safe. An unnamed disgruntled employee ransacked Tim Kingsbury’s desk one day in 1996. The employee hit the jackpot: an envelope containing forged Wisconsin birth certificates, blank social security cards, and a piece of linoleum carved into a seal for Dane County, Wisconsin. The district attorney was notified, the station was searched, and the fake documents confiscated. Even in creating his new identity, Patrick Welsh could not let go of his old one. On his phony birth certificate, he gave his mother’s real maiden name. And the county official who “signed” the certificate was “Richard A. Welsh,” his father’s name, written in the exact way that his father penned his signature.

Tim Kingsbury had forged official documents, a felony. But he did not go through the normal booking, fingerprinting, or photographing process, nor was his crime reported to the Daily News. Before the case went to court, an Ohio lawyer arranged for Patrick Welsh to pay the $10,000 balance that he still owed for his embezzlement in return for all charges against him being dismissed. That a dead man was making restitution and getting charges dropped should have raised some eyebrows. But the embezzlement had taken place in Columbus, the declaration of death had occurred in Lancaster, and Elizabeth Welsh had by then moved to nearby Newark to take a better job. Never did the right hand find out what the left hand was doing. Back in Galveston, Patrick Welsh was allowed to plead guilty, pay a fine, receive probation, and go on being Tim Kingsbury in public, although he was required to use his real name on all government and financial records.

On the day of the ransacking, he did the same thing he had done in Lancaster when he was caught embezzling—called a “family meeting” (Ann, Vandy, Vandy’s wife) to reveal the truth. After the court case, many people knew his real name, from the judge to the clerks in the courthouse, and they all kept the secret of his identity. It would be more than a year before the truth came out—not in Galveston, but in Ohio.

I found a good home for the dog today. Ted and Chris cried. They don’t understand that we can’t have any pets in our apartment. I can’t afford pets, at any rate. We will be lucky to stay in peanut butter. I am finding out that Pat left us in much worse shape than I had originally thought. The Club called, though, to tell me that they have forgiven his debt. It was all golf and past dues. They really couldn’t hold me accountable anyway, because Pat is the member. Was the member.

—undated excerpt from Elizabeth Welsh’s diary, spring 1983

He was the best catch in the class, and she was the prettiest girl. The sixties style suited her perfectly: long, silky blond hair; big, clear hazel eyes; long, slim athletic legs. She played tennis and rode hunt seat; he played football. They knew during their junior year in high school that they would get married, and so did everyone else. They were Pat and Peachie—a nickname her father had given her at birth because, he said, her skin was all peaches and cream; as she grew up, she was glad to have it, because her real name was Freda Ellen Elizabeth Shank. As a young husband, he adored her so much that he couldn’t take his eyes off her; he went around their A-frame house in the country with a camera in hand, taking unposed photos of her. How does such a love story end up in a reunion in the Licking County jail after fifteen years of separation and silence?

I know only Elizabeth Welsh’s version, since Patrick Welsh isn’t talking. She, on the other hand, will answer any question (Q. Did you get a make-over before you saw him again? A. No, but I changed my hair, which is strawberry blond, from redder to more blond). She knew that media interest in the story of the man who had risen from the dead would be intense, and she decided to control the story before it controlled her. “It’s a story in which I am a main character, that I must claim as my own,” she told me.

I met her at the offices of the Newark–Licking County Chamber of Commerce, four blocks from the nineteenth-century courthouse where Patrick Welsh was scheduled to go on trial at the end of April. Her title is president. She has been recognized as one of the ten most influential women in her part-rural, part-suburban county of 165,000—not bad for a woman who dropped out of college to put her husband through school and was working in a dress shop when he deserted her. Connoisseurs of irony will note that Patrick and Elizabeth Welsh accomplished far greater things in their separate lives than, in all likelihood, they would have accomplished had they stayed together. Both reinvented themselves; he because he wanted to, she because she had to. Like her former husband, Elizabeth Welsh could also pass for at least ten years younger than her age of fifty. She was strikingly attractive in a grown-up way: the silky blond hair, now coiffed into a flip; no perceptible facial wrinkles; and an engrossing air that seemed to combine both strength and vulnerability. As she talked, what came through was neither anger nor bitterness but a bemused awe at the turns her life has taken. “The embezzlement, the desertion, it’s like it’s happening all over again,” she told me. “Once again I see people whispering wherever I go. Long-suffering Saint Elizabeth of Newark. I got hit by the same bus three times.”

For a long time she didn’t think he was really dead, despite the suicide letters. After phoning her throughout the day of his disappearance, Pat had been a no-show at her father’s house, where she was waiting for him. At midnight she went out to search the icy roads for an accident. The first letter (“I’m doing the best thing for you”), postmarked Lancaster on the day he disappeared, arrived four days later. A second one, postmarked San Francisco, followed in three weeks. “He said that he would look down on the boys and me from heaven and watch over us,” she said. “Unless he killed the devil within him, he would corrupt everyone around him, and he couldn’t do that to us, those he loved above himself.” But there were clues to suggest that the suicide was a false trail. An investigator found trash from a laminate-your-own ID card stuffed away in their garage. Pat had sold his car and taken most of the proceeds with him; of what use was money to a dead man? If, as was likely, he had just run away in shame and despair, then he would be caught, the investigating authorities assured her. For thirteen years, Pat’s Christmas stocking continued to be displayed when the huge Welsh clan gathered, including Elizabeth. His mother died of cancer, and Elizabeth inspected the church at the funeral for someone who might be Pat in disguise.

The break came early last November, eleven months after Tim Kingsbury had been ordered, as a condition of his probation, to use his real social security number. Elizabeth Welsh got a form letter from the Social Security Administration (SSA) demanding repayment of $54,000 in benefits she had received for her children and giving her thirty days to pay. The reason was: “Number holder not deceased.” By this time she was sure Pat was dead; someone was trying to use his old number as a false ID. All she had to do was find out who, and she would be off the hook. But when she tried to get more information, SSA officials in Newark said they could tell her nothing. They were silenced by the Privacy Act of 1974, which apparently protects the guilty and torments the innocent.

Even the intervention of her congressman, House Budget Committee chairman John Kasich, didn’t stop SSA from stonewalling. But Kasich’s office was able to pry two facts out of the bureaucracy: The cardholder was in the Southwest, perhaps Texas, and he had committed some sort of crime. “Are you sitting down?” Kasich’s senior aide said to Elizabeth. “I think this might be Pat.”

Elizabeth had told a few friends about her dilemma. One had suggested looking at a driver’s license database on the Internet. Now that she had a state to check out, she typed in “driver’s license information.” Sure enough, there was a company that had the information for Texas—for a price. At the bottom of the page was a phone number, and she called.

“My heart was beating so hard, I could see my blouse move,” she told me. “I told the person who answered I wanted just one name. He must have sensed my desperation. I gave him Pat’s social security number, and it took two seconds. ‘Patrick H. Welsh,’ he said. ‘Five feet, nine inches; one hundred fifty pounds; green eyes; brown hair; must wear glasses to drive; 6828 Driftwood Lane; Galveston, Texas.’ It was Pat.”

The rest was easy. A search of the address yielded the names Tim Kingsbury and Ann Anderson. She found his e-mail address, decided that was how she would contact him, and deliberated over what to say. The message she chose was: “I know. Call me to discuss this. Peachie.”

If Tim Kingsbury had responded, he might still be in Galveston today. But he didn’t. After two weeks went by, she called him at KGBC. “Let me change lines” he said, and then, “I knew this day would come. I just didn’t think it would be you who would find me.”

“You must do three things,” she told him: contact the SSA and his former insurance agent about repayment and—this was the test—come clean in Galveston about who he was. “It’s unfair for you to take another community down with you,” she said.

“I can’t do that,” he said. He had flunked.

Through a lawyer, he opened negotiations for repayment, but the one thing Elizabeth Welsh really wanted, some sign that Patrick Welsh was ready to face up to the past, was nonexistent. He hadn’t even asked about his children or his family. “He didn’t kill himself,” his younger son, now 23, told his mother. “He killed all of us.”

In January she decided to file felony charges against him for criminal abandonment. “I couldn’t say to my boys, ‘It was okay what he did,’” Elizabeth told me. “I didn’t want them to think that men could run away.”

But before the authorities brought him back to Ohio, she went to Galveston incognito. She drove past the house on Driftwood Lane and saw the amazing Tim Kingsbury leave for dinner with Ann Anderson. She saw the handsome nineteenth-century homes amid twentieth-century decay. And she went to see KGBC, on mostly undeveloped Pelican Island in Galveston Bay, and puzzled over the aging flat-roofed building that is half-obscured by shrubs and grasses. “It looked like a place for dumping bodies,” she said. “I had the inexplicable feeling that there were undercurrents here that I could never understand.”

“There are in fact real victims who have been inflicted with real harm, perhaps worse than can be inflicted with a knife.”

—Licking County Prosecutor Robert Becker, arguing against reducing bond for Patrick Welsh

The February reunion of Pat and Peachie was an anticlimax. She could not feel a scintilla of warmth pass between them. “He looked at me like I was a porcupine and he was a dog,” she told me.

I saw him before his bail reduction hearing the day after my meeting with Elizabeth. He was a solitary figure sitting on a bench in the near-empty courtroom, oblivious to the ornate decor that included stained-glass windows and a dome. He wore his jail garb of jeans, a T-shirt, and a blue denim jacket draped over his shoulders. I didn’t recognize him at first because he was so gaunt. His most prominent feature was his Adam’s apple. When I turned back to him, he said, “Hi, Paul.”

“Hi, Tim,” I said, forgetting who he was. “Can you talk?”

“My attorney says not to,” he said and shrugged. As he did, a clanking sound came out from beneath his jacket, and I realized that his wrists were shackled. I moved away. The man who had been Galveston’s civic leader shuffled up to the defense table, his movements restricted by ankle chains. Robert Becker, the chief prosecutor, took his seat to represent the State of Ohio. I took that as a bad sign for Pat Welsh. I had watched three other cases that morning, all handled by assistant prosecutors. Now the top man was after him. The odds are high that Patrick Welsh is headed for the penitentiary.

After the brief hearing, he shuffled out to see Ann Anderson. I wanted to feel sorry for him, but I couldn’t. He had conned my friends and my town, and whatever good he had done had been eclipsed by feelings of mistrust and betrayal. Only a few people, most of them friends I had known all my life, were standing by him. They were the ones who had suffered most, except for Elizabeth, of course, and the boys who had grown up without a father. Once again, Patrick Welsh had managed to hurt those who loved him most.

I thought of something the lawyer who had called Tim Kingsbury “a nonprofit kind of guy” had told me. “The news about Tim was coming out at the same time as the Karla Faye Tucker story,” he had said, “and I thought about her a lot. Here was somebody who had tried to redeem herself, but there was nothing she could do to bring back those two people she had killed. For three hundred and sixty-five days a year, for fifteen years, all Tim Kingsbury had to do to redeem himself was pick up the telephone and make one call. And he didn’t do it.”