This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

She loved everything there was to love about the neighborhood, from its park teeming with weekend volleyball fanatics to its quiet avenues sprinkled here and there with strolling old folks and college students. Raised in Austin’s southwestern suburbs, she moved to inner-city Hyde Park in 1980 and thereafter came to think of it as her home. From the balcony of her small, sunny garage apartment, she could squint past the treetops at the blocks and blocks of fifty-year-old bungalows—some upright and well scrubbed, others in quiet disrepair.

A slender and athletic girl in her twenties with an easy smile, she worked the afternoon shift at a nearby hospital and often commuted by bicycle. Neighbors would see her come and go, and would call out her name. Like the patients who stayed in touch with her long after leaving her care, they came to rely on her radiant presence, taking it for granted that she would always be among them. “She felt so comfortable with herself,” said the older woman next door, who was her close friend, “and comfortable with the world.”

Such was the Hyde Park world of the nurse before the night of Friday, January 17, 1986—the night she returned home from a dinner date, opened her apartment door, and was blindfolded, gagged, and bound with nylon cords by a stranger with a gun who was waiting for her in the darkness and who told her what he wished to do with her and did it.

It was a night she survived. Thereafter she sought to reclaim the life she had once lived. She returned to her apartment with a friend the following day, and together they scrubbed away the fingerprint dust, doing all they could to wash out every trace of him. A day later, she went back to work—determined, she said, “to go on, as if it didn’t happen.”

He waits for them in their homes—unknown, unseen, only a voice: “I’ve got a gun and I’m not afraid to use it.

“People tell me I ought to move,” she told a friend. “But I don’t want to! I’ve got to get over this! I’ve got to get above this! I won’t let this ruin my life!”

She had friends stay with her, first one and then another. But the cocoon had been shattered. She found that some of her neighbors in Hyde Park, though kind as always, simply did not know what to say to her after hearing the sirens that night and the rumors that had followed. A year after the attack, she packed her bags. It was time to leave Hyde Park, time to get on with her career. She would find a new city, new patients, and from her new residence would see a new neighborhood’s panorama unfold.

But she never saw him, not even for a second.

The nurse did not know about the Hyde Park Rapist. Neither did anyone else, including the police. Five years since the first known attack, the Austin Police Department has developed an enormous volume of leads relating to the city’s longest-running unsolved serial rape case. Yet the man in charge of the investigation, Sergeant Paul Johnson, admits, “We haven’t gotten anywhere. We may not be any closer to figuring out who he is now than when we started.”

What the police do know is that he has committed far more assaults than the seven publicly attributed to him. And they know that several factors—the lack of communication between law enforcement entities, the makeup of the Hyde Park neighborhood, the elusive personality of the rapist, the abundance of women who are vulnerable to his attacks—have collided all at once and made the case of the Hyde Park Rapist one of the most frustrating imaginable.

The case is filled with ifs: If a woman was to actually see his face . . . If some clue of his origin was available . . . If his extraordinary luck was to give out, just once. . . . But the biggest if is seldom spoken aloud: If his attacks were more frequent. For if they were, his trail would be evident and his terrorism would command urgent attention. Police officials say they would swarm the neighborhood. Residents say they would form a posse. Not a soul would rest until the inevitable capture of the Hyde Park Rapist.

But the rapist will not oblige this unspeakable request. He will neither conduct a reckless rampage nor disappear altogether. His is a persistent but obscure presence. By his cautious methods he has given the neighborhood—especially its entrenched residents, the least prone to his attacks—the opportunity to ignore him.

And many have taken that opportunity. Why they have done so can in part be explained by the way inner-city communities look at themselves. Like the Heights in Houston, Lower Greenville in Dallas, and Laurel Heights in San Antonio, Hyde Park’s charm lies in its patchwork composition—as much a state of mind as a state of appearance. Far from marring the community, the tattered seams and eccentric behavior distinguish such neighborhoods from suburbia. Tolerance has its limits, of course, as Hyde Park has shown in its well-publicized struggle to prevent its neighborhood Baptist church from demolishing old residences. But when a problem does not threaten the soul of the community, it ceases to become an issue. Instead, it works its way into the patchwork, the rough that goes with the smooth. A few neighbors will let their houses go to seed; bicycles will be stolen; vagrants will doze in the parks. And on a rare occasion, it is conceded, a single woman who did not lock all her windows will be assaulted. This is how Hyde Park regards its rapist. He is a defect in the patchwork that its residents have learned to live with and would rather not discuss.

Today his victims fear that he is watching them still, wherever they might be, and that he will finish the job.

Few in the neighborhood know more about the rapist than Barbara Gibson, who reports on crime for Hyde Park’s newsletter the Pecan Press. Often her column has alerted residents to his attacks. Yet she says of the publicity surrounding the unsolved cases, “It has stigmatized the neighborhood. Would you like to live in a neighborhood that has its very own rapist? And I’m not sure the number of rapes in Hyde Park is statistically higher than elsewhere. I think it’s been—what—four rapes in four and a half years? One a year. You say, ‘Hyde Park Rapist,’ and people think someone’s attacking once a month.”

Gibson’s numbers are way off. But the misinformed beliefs persist that the rapist appears only annually, like some evil groundhog; or that he was arrested years ago; or that he was the young man who murdered a female college student, Hyde Park resident Tiffany Bruce, this past October and subsequently fled to Hollywood, where he jumped to his death. The most popular myth is that the Hyde Park Rapist is a fluke, a neighborhood anomaly rather than a neighborhood symptom. But the grim fact is that though this particular rapist’s five years of crimes have earned him a nickname, he is neither Hyde Park’s first serial rapist nor, likely, its last. “There are other areas in town that have a much higher incidence of rape,” says the police department’s senior sergeant in charge of sex crimes, Hector Reveles. “But I will say this: Since I’ve been here, a disproportionate number of the serial rapists we’ve arrested have been from in or around that area.”

In the case of the Hyde Park Rapist, says Sergeant Johnson, “The actual numbers are something we’re not going to disclose.” Johnson suggests that body-counting is a ghoulish media game. The result, however, is that the police have informed neither the neighborhood nor the media of several attacks. Investigators say they’re protecting the leads they have generated over the past five years, hoping that they might one day bear fruit. But frustration also explains their reticence. As Sergeant Reveles notes, “One of the big cons in putting something out in the media is that you get so many wild leads, and you eventually have to track them all down.”

So the police have stopped talking, the neighborhood has stopped asking, and the damage done by an unseen man is scarcely comprehended—except by his victims. Though some of them agreed to be interviewed for this article, others did not. These women were individuals, and remain so after the assaults on them. They have each dealt with their profound humiliation in their own way.

One of the few sentiments these women share is their desire to remain anonymous. They want this because they fear for their lives; also because they recognize that discomfort over the subject of rape extends far past the boundaries of Hyde Park. For it is not merely a crime rooted in society’s violence but also one that flourishes in society’s ignorance. It is a crime, says Mitzi Vorachek of the Houston Area Women’s Center, “that is still regarded not as a crime, but as an act of sexual lust, still tied up with the old romantic myths of Rhett Butler carrying Scarlett O’Hara up the stairs against her will.” And it is a crime that inspires fear, discomfort, and revulsion—human emotions that produce the only thing a crime needs to perpetuate itself: silence.

If you want an easy situation in life, you could buy a tract house in the suburbs,” says Hyde Park realtor and resident John Sanford. “But this neighborhood has attracted a lot of can-do people. When we first moved here in 1977, you could hear the hammers banging and the saws scratching every day after work. You could see this old neighborhood was coming back.”

Sanford and his wife and business partner, Hope, embody the aggressive optimism that saw Hyde Park out of its period of neglect during the sixties. Like other active members in the Hyde Park Neighborhood Association, the Sanfords view themselves as liberals who celebrate traditional community values. They’re also people who don’t wait around for someone else to solve their problems for them. Dissatisfied with the sparse appearance of nearby Shipe Park, they helped in a major fundraising drive to refurbish the playground. When it became clear that the city wasn’t going to save the neighborhood’s crown jewel, the Elisabet Ney Museum, from decay, Hyde Park’s activists again persuaded neighbors to mount another fundraising effort. Saving the fire station from closure, fighting Hyde Park Baptist Church’s plans to turn home lots into parking lots, chasing the nearby city airport out of the area—the Sanfords and their neighbors have never ducked an opportunity to inch Hyde Park closer to their warm, thriving vision of what a community ought to be.

The socially relaxed feel of the area (bordered by Guadalupe to the west, Duval to the east, Fifty-first Street to the north and Thirty-eighth Street to the south) has drawn more than young professionals. Many residents are University of Texas students and recent graduates who inhabit modest duplexes and garage apartments while beginning their climb up the vocational ladder. Though they may show little interest in neighborhood politics, their affection for Hyde Park resurfaces later. Says James Allman, the former president of the neighborhood association, “Most of the people who are making investments in renovating homes are people who previously lived in the area as renting students. They loved the neighborhood back then, and when they became ready to strap on a mortgage, they returned.”

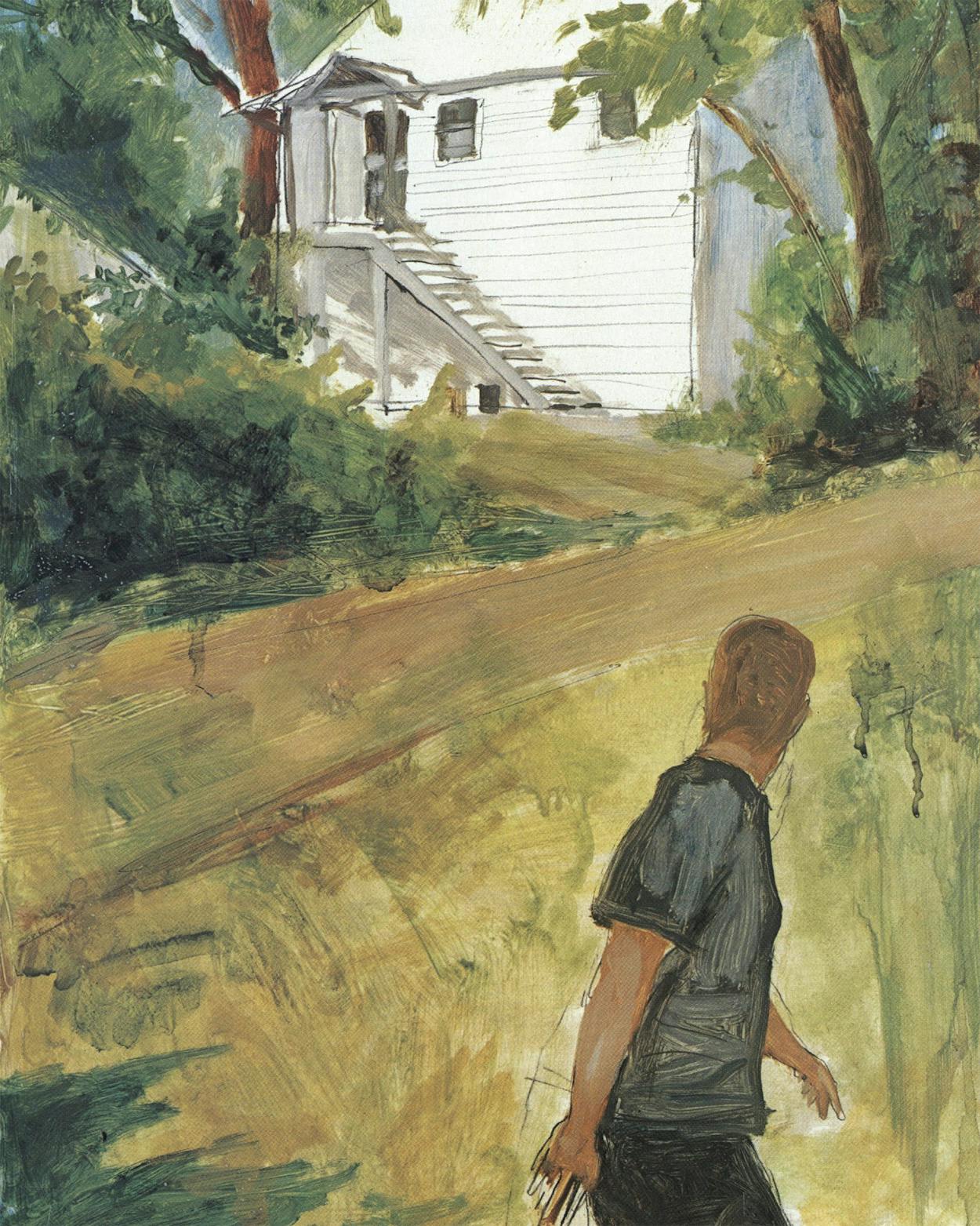

Among the young renters in 1987 who hoped to buy property in Hyde Park someday was a brilliant and physically striking law student. A product of Houston’s Spring Branch suburbs, she loved the funkier charms of Austin; to her, Hyde Park was “an Austin kind of neighborhood, entirely natural and laid-back.” She walked to campus daily from her Avenue G duplex. An alley separated her from a neighbor, an elderly woman who shared her fondness for gardening. While they stood in their respective yards and chatted, students walked between them, heading north or south along the dirty alley.

The law student could not have known who else walked up and down the alley. She could not have known that when she drove to and from Bennigan’s every Friday night to drink with friends, someone watched from the alley. For that matter, she knew nothing about the garage apartment down the road and what had happened eighteen months earlier to the nurse who once lived there.

Late on the Friday night of July 3, 1987, she opened her front door, walked in, and was grabbed from behind in the darkness. “Shut up,” he said to her. “I’ve got a gun, and I’m not afraid to use it.”

He handcuffed her, then gagged her with a bandanna and pulled a pillowcase over her head. He dragged her out of the living room and forced her to kneel by the foot of the bed. With a nylon cord, he began to tie her arms together. He fashioned one knot, then another, then several more—far more than needed to restrain her. He took off the handcuffs. Then he took off her jeans and lifted her onto the bed.

Using more nylon cord, as well as several of her belts, he bound her ankles to the bedposts. The process, knot after knot, seemed to take hours. She felt that once he finished tying her and raping her, he would surely shoot her and leave her there, a corpse bound to her bed. But perhaps not. In the flush of that dim possibility, righteous anger surged within her. The words flashed in her mind: Do not fight. Let it happen. Re- member everything.

He ripped her blouse open with a large knife. Then, through the pillowcase, she could make out the rather slight figure moving toward her chest of drawers, rummaging through them, a pair of her pantyhose pulled over his head. He returned to her with a jar of her lotion. He rubbed it on her breasts —slowly, as if trying to arouse her. He began to lick the lotion off of her. His face felt absolutely hairless to her; she could smell no alcohol on him. Remember everything.

He raped her, then loosened the bonds on her wrists before he left her. The police responded to her call two minutes later. They kicked open her door, rifles drawn. “He’s already gone,” sobbed the law student. She was naked and still tied to the bed.

On a springtime Saturday in 1988, a young woman marched into the office of the Austin Police Department’s sex-crimes division. She was furious, and became more so after she happened to glance at a detective’s desktop computer. There, displayed on the monitor, were five or six sexual assaults that had occurred at Hyde Park addresses. “How come all of a sudden there’s a Hyde Park Rapist,” she snapped at the detective, “and we never heard anything about it?”

The woman had a particular reason to be upset. She was a Hyde Park resident. Two nights previous, a woman who lived in her back yard in a garage apartment had been tied up and raped by a man wearing a ski mask and carrying a gun. Like another before her, the victim had been a nurse, a bright and pleasant thirty-year-old woman. The morning after the attack, her brother drove to the garage apartment and collected her belongings. She would never set foot in her home again.

For the victim’s neighbor, the Hyde Park resident questioning the police, anger melded with dismay. On any other night that spring, she and her husband would have had the windows open and would have heard the nurse return from her 3:00 to 11:00 p.m. shift. But this had been one of the season’s cold nights; they had shut the windows. Her screams had gone unheard.

The rape case was assigned to a ten-year Austin Police Department veteran, Sergeant Paul Johnson. He was a relaxed and deliberate man with a wry sense of humor who had been transferred into sex crimes only a month earlier. “By the way,” Johnson was told by his boss, Senior Sergeant Reveles, “it looks like it’s going to be related to others.” Thus did the unit’s least experienced sex-crimes detective inherit its most difficult investigation.

Reveles saw Johnson’s newness as an advantage: It meant he wouldn’t be leaving the unit anytime soon, as previous investigators had. There would be more cases, Reveles suspected, and “I thought it was important to have some continuity,” he said. The investigation also required a man capable of organizing numerous and disparate leads, capable as well of treating rape victims with sensitivity and respect. Paul Johnson possessed those qualities.

But the police would need more than a sensitive middle manager to catch the rapist. That was clear long before Johnson joined the sex-crimes division. Though the January 17, 1986, attack on the nurse was the first reported incident, the assault seemed too well planned to have been the rapist’s first effort. An early suspect, a 24-year-old nightclub employee, hadn’t panned out. A composite sketch, based on descriptions of a prowler after the July 3, 1987, assault on the law student, was shown to the victims. None of them, however, had gotten a good look at the rapist. They only knew that he was white, soft-skinned, of slight-to-average build, with blond-to-brown-colored hair, probably in his twenties, and possessing a voice that had, as one victim said, “no distinguishable accent.” Perhaps half of Hyde Park’s male residents fit such a description.

Still, a criminal pattern had emerged. All of the rapist’s victims were white, single women, aged eighteen to thirty. They all lived in apartments or duplexes that backed up against unlit alleyways. Their evening comings and goings were known by the rapist, because in all of the cases he was in their homes waiting for them, having entered by an unlocked window or door. His attacks occurred around midnight—and oftentimes, it appeared, on or near holidays: Thanksgiving Day, the Fourth of July, Martin Luther King Day, St. Patrick’s Day.

Following an attack on November 28, 1987, Reveles asked Lieutenant Ed Richards, of the Texas Department of Public Safety’s Criminal Intelligence Service, to compile an “investigative assessment” of the Hyde Park Rapist. Richards, a respected authority on rapists, compared the Thanksgiving weekend attack with those on the nurse and the law student. He concluded, both in the report and in subsequent interviews, that the assailant was a “power-reassurance rapist,” who used only the amount of force necessary to dominate his victims and thus to reassure himself of his masculinity. Like many such rapists, the man in Hyde Park seemed to Richards to be of at least average intelligence and perhaps even had a sexual partner. But because of his low self-esteem, he was likely an underachiever who had not attended college and probably lacked the confidence to date the kind of women about whom he fantasized—the kind of women he would target as his victims. From his midnight rovings, it appeared that the rapist was not accountable to a wife. His holiday assaults suggested that he lived elsewhere and came to Hyde Park to visit family during vacations. On the other hand, the extent to which he monitored his victims strongly hinted at the opposite: that he spent a great deal of time in Hyde Park and perhaps even lived there.

That the rapist elaborately planned his attacks, stuck to one neighborhood, and tied his victims seemed to Richards to be explained by a single desire: “for complete control, something these kinds of rapists are unable to accomplish in their normal life. . . . They commit their crimes where they feel secure. Security comes from familiarity. He’s not the type to drive down to San Antonio and commit a rape.”

Yet Lieutenant Richards’ investigative bottom line was not a promising one: This man, however insecure and withdrawn, “would not be suspected by friends and acquaintances of being a rapist.” In sex-crimes investigations, that was a familiar refrain. In the late seventies, a Dallas patrolman arrested the city’s notorious Friendly Rapist (so named for his apologetic treatment of his approximately 75 victims). The assailant turned out to be Guy Marble, a prominent advertising executive with a wife and children. In late 1985 the Houston Police Department discovered that the Voss Road Rapist—responsible for as many as 30 to 50 assaults—was a handsome, popular man named Sandy Sanderson, who had once been a high school quarterback near the area where he conducted his attacks. And in June 1988, when the Dallas Police Department declared that it had arrested the Village Rapist and had closed the books on 21 cases, friends of the rapist protested vehemently. Surely Greg Goben, the loving husband, community leader, and Baptist minister, was not the same man who had tied up women, taunted them, and forced them to wear certain clothes before raping them. But the fingerprints matched, and Goben—along with Marble and Sanderson—is now the property of the Texas penal system.

Each of these rapists left a densely littered trail of victims. The Hyde Park Rapist had not—or had he? His 1986 assault on the nurse was extremely well planned; perhaps, in some other city, there existed a trail of earlier, clumsier attempts. Unfortunately, the Austin Police Department had no way of determining this. Their data base system can keep track of former inmates out on parole and the like, but it’s a local data base. It doesn’t help unless someone from Austin commits a crime in Austin.

Paul Johnson thus began his investigation with the glum knowledge that none of the victims had seen the rapist’s face, that he would not be able to tap into the information of other cities or states to determine the rapist’s origin, and that he would be saddled with scores of other cases involving sexual assault, window-peeping, suspicious-person complaints, and indecent exposure. Short on time and resources, Johnson could only hope that his luck would improve—or that the Hyde Park Rapist’s luck would falter.

When the story first broke in the spring of 1988, Hyde Park responded decisively. In April, Barbara Gibson began her crime column for the neighborhood newsletter, and residents directed a steady stream of calls and letters to police headquarters, demanding that the police provide her with information. By June, Gibson was granted access to the police department’s media computer, which contains all criminal reports that have been filed. But the reports didn’t say much beyond the date, type, and location of the offense.

When Gibson asked for a description of the suspect, Sergeant Johnson would only say, “a young white male.” In her July 1988 column, Gibson advised, “Be alert to strangers who act inappropriately or who have no apparent business in the neighborhood.” Residents responded with hordes of suspicious-person calls. Policemen gathered “literally hundreds” of photographs of “strangers” seen in the area, according to Sergeant Reveles. It fell to Sergeant Johnson to examine and organize the photos —a huge investment of time that resulted in no arrest. Of course, Johnson had not informed the crime columnist about Lieutenant Ed Richards’ analysis seven months before, which concluded that the rapist was hardly an outsider, but rather someone who “is very familiar with the Hyde Park area and possibly lives or works in the area.”

Discussions about crime and safety continued at neighborhood meetings. The association went so far as to field offers from East Austin neighborhood patrols. But a desire for normalcy gradually overtook Hyde Park. Established residents put new locks on their doors and windows and went on with their lives. People began to resent the nickname given to the rapist. Often they would cite the untrue rumor that the assailant had also struck in adjacent Hemphill Park. Noting the neighborhood’s behavior, Tonya Edmond, the Austin Rape Crisis Center’s client-services director, said, “To try to make themselves feel safe, people buy into a lot of denial.”

At the monthly meetings of the Hyde Park Neighborhood Association, a new concern crept into the dialogue. “There are new couples moving here,” some said. “We shouldn’t scare them off with talk of this rapist.” In the same breath, neighborhood boosters declared Hyde Park a special place and yet—in the area of rape—no different from anywhere else.

A young woman who attended one of those meetings was appalled: “A lot of the people were more concerned with property value decreasing if we hyped this thing up,” she recalls. She suggested a “take back the night” march through Hyde Park, and was advised by the neighborhood association that she was on her own. A few months later, she saw a man looking at her through her alley-side window. Instead of marching, she moved out of the neighborhood.

Whether a neighborhood march might have been effective depends on the objective. Such a march took place in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood in the summer of 1990. There were no resulting arrests; however, so far the Montrose rapist has made no further attacks. That neighborhood’s response was a strong one, yet it was also fraught with the inner conflicts rape inspires. Following a series of rapes, a local organization known as Women Against Violence Everywhere began to march in the neighborhood and distribute leaflets to residents. “The reign of silence is ending,” said the leaflets. “Women must set aside their fear and employ their anger to proclaim that they will not tolerate violence and will no longer conspire with those who urge silence and resignation.”

As a means of showing solidarity, WAVE members proceeded to draw silhouette figures on the intersections nearest each assault, inscribing the date and “rape” or “attempted rape” next to each figure. That such a tactic might seem like a scarlet letter to already traumatized victims was apparent to many, but not to WAVE. “The controversy over that was ridiculous,” said WAVE co-founder Jacsun Shah. “Women have bought into the myth that rape is shameful or degrading, when they themselves have done nothing.”

Yet Shah has not been raped herself and acknowledged, “It’s hard to speak for someone who’s been through that terrible experience.” Among those who did not accompany Shah in the WAVE marches was a woman down the street from Shah’s house who moved out of Montrose immediately after being raped.

In May 1988 a serial rapist was arrested on the outskirts of Hyde Park. A couple of days later, while watching television in the Travis County jail, the suspect heard a broadcaster declare, “Austin police have apprehended the Hyde Park Rapist.”

“Congratulations,” the inmate told Senior Sergeant Reveles the following day. “I heard you nailed that Hyde Park Rapist guy.”

Reveles shook his head and smiled ruefully at him. “They think it’s you,” he said.

The man in custody had committed sexual assaults in and around Hyde Park, but he was a different serial rapist altogether. He was a tall, soft-spoken Ohio fugitive who went by the name of Randy Vogel. Like the Hyde Park Rapist, Vogel planned his assaults well and took great pains to blend in with other neighborhood pedestrians. He described to Reveles and Johnson his methods and motives. Then he surprised them with a revelation.

Recalls Vogel from a prison-farm visitation room, “After they gave me his description—well, the thing is, I’d seen this guy a couple of times in the neighborhood. Matter of fact, he went to a house I’d had my eye on and checked it out himself while I was over in the bushes of a house across the street.

“He come around the front, picked up a two-gallon bucket, and took it around to the side and stood on it, looking into this woman’s bedroom. After he looked in for a while, he left. I seen him about a week later in another part of the area. He had on a windbreaker jacket turned inside out where there wasn’t a zipper shining. And he had on a dark T-shirt and what looked like stretch-knit pants. His hair was reddish-blond and sticking out from behind his collar.

“At first I thought he was a burglar. But the house wasn’t the type that you’d get anything from if you were a burglar. Then I learned later what was going on in the neighborhood.”

The luck of the Hyde Park Rapist finally began to change. On June 13, 1988, at 10:47 p.m., a nineteen-year-old college student entered her garage apartment. From the doorway he lunged at her, grabbed her, and showed her a knife. But she was a tall, strong girl, and she pulled the rapist back outside with her. For several minutes, they struggled in the carport. Then the rapist fled on foot.

Five months later, a 22-year-old student sat in her garage apartment bedroom with the front door wide open, hoping to hear the raccoons that congregated in the garbage cans below. While sitting on her bed and reading the paper, she looked up to see a young man walking into her house. At first she thought it was her boyfriend. Then she saw the blue bandanna over his face, the ski cap on his head, and the gun in his right hand.

He covered her mouth with a gloved hand. “Don’t scream,” he said. “If you do what I say, I won’t hurt you.”

She assented, and he leaned her over the bed and prepared to tie her wrists. She knew he was the Hyde Park Rapist; she knew he would rape her; she figured he would kill her when it was over. Then she felt the gun on the floor next to her leg.

She swung around before he could tie her hands together and grabbed him by the arms. They wrestled against the bed. She fought for her life, feeling the strength of her life. It dawned on her, as their arms swung crazily back and forth, that he could not overpower her. It dawned on him as well.

“Okay,” he said suddenly. “I’ll leave.” He stood and reached for the pistol on the floor. “Leave it,” she said.

“Are you crazy? No way!” He scooped up the gun and rushed out. She then lunged for the door, locked it, and dragged the phone into her bathroom and called the police.

Following the attack of November 11, 1988, the Austin Police Department finally released the investigative analysis to the media. Composite drawings were circulated among residents. (“He looks like John Boy without the mole,” one woman commented after seeing the drawing.) “The Hyde Park Rapist has struck yet again,” wrote Barbara Gibson in the Pecan Press, which printed excerpts of the analysis. A new round of neighborhood vigilance ensued, along with more names and photographs for Paul Johnson to consider.

Then there was quiet. The year of 1989 brought no news of investigative breakthroughs. The police reported no attacks by the Hyde Park Rapist. Gibson’s crime column returned to petty thievery and other mundane topics. It was as if a black cloud had lifted, never to reappear.

Recalling that moment of calm, John Sanford said, “I’ve heard stories on television where a serial crime stops, and the police discover they’ve got the guy in jail on another charge. My thinking was, perhaps he had been arrested for something else.”

But he was still among them, a bland and introverted figure passing unnoticed through the alleys. Why he did not attack for several months is a mystery probably even he could not explain.

Throughout those months, the awfulness still throbbed within him. The people in his normal life, the life in which he felt so helpless, did not know this about him. In a horrible sense, his victims understood his pain better than anyone else. I’ve got a gun, and I’m not afraid to use it. How many times had he rehearsed that line before it finally sounded right? How many nights had he sat in his room, tying one knot and then another, thinking that he might one day tie up his own life in a neat little bundle?

Did the screams and pleas of his victims ring in his ears? Probably not, said Jan De Lipsey, a Dallas psychotherapist who treats rapists: “Even those who can express remorse really have no idea about the consequences of their actions. That’s part of what allows them to do this in the first place.”

Convicted serial rapist Randy Vogel agreed. “There were times I thought I was doing battle for all the guys in the world,” he said, “and other times when I knew I was nothing more than a pervert. At other times, though, I just felt that this is what I was born to do—and to try to accept it and go on with it.

“Most of the time I could tell myself that everyone who walked in a dress was a whore or a cheater and was going to hurt somebody sooner or later. Through this I could hide the guilt. But every now and then you’d come across someone who’d radiate this innocence about her, and there’s no lies you can tell yourself.

“There was one in Austin; to this day, I come up with these guilt feelings. She was just like the rest. She cooperated. But all I can remember about her is that, more than anything else, I would have given anything in the world if she had been the one, the one to say, ‘Come in,’ and we would have been together under mutual consent, instead of waking her up into a nightmare.”

Did the quiet months of 1989 find the Hyde Park Rapist wrestling with similar agonies? Or was he too sick to care? The term “sick” is not preferred by law enforcement officials: As Dallas police Sergeant Larry Lewis put it, “They all know what they’re doing, and they know that what they’re doing is against the law.” But, Lewis conceded, serial rapists cannot seem to stop themselves. “In my experience, I can’t think of any such instance,” he said. “Instead, he’ll usually get more violent in his crimes or his crimes will occur more frequently.”

That did not happen in 1989 either. But the rapist’s dark view of Hyde Park persisted. He saw the neighborhood’s unlit alleyways. He saw the dozens and dozens of single women, living casually in rickety dwellings, leaving in the evening and returning at the approach of midnight. His was a crime of opportunity, and here the opportunities were plentiful. More and more home renovators were turning their garages into apartments. More and more young women were moving in, a fresh crop every semester, perfectly unaware of him. In his disturbed, perhaps crazy mind, it is possible that he thought, I would be crazy to leave.

Six weeks after the attempted burglary of her Hyde Park garage apartment on March 17, 1989, a wholesome-looking corporate-meeting planner received a call from, of all people, a sex-crimes investigator.

“I’m working on the Hyde Park Rapist case,” said Paul Johnson. “Do you mind if I come take a look at your apartment?” She had never heard of the rapist. When Johnson arrived, she retold her story of the break-in. She had gone out the night of St. Patrick’s Day, deciding for the first time in years to make a long evening of it. She returned at about three in the morning. Leaving her apartment later that morning, she noticed that the window had been pried open, and in fact was still cracked a few inches. Nothing had been taken, however, so she deduced that the burglar had not been able to force open the window.

Johnson listened. Then he walked over to the window and gave it a push. The window slid all the way up. Then he pushed it back down, but could only manage to return the window to its original open position. The young woman gaped in confusion.

“He got it all the way up,” the investigator told her. “But he couldn’t get it all the way down. He was in here, waiting for you, probably till around midnight, which is normally when he attacks. And when you didn’t come home by then, he left and tried to pull the window down but couldn’t.”

Johnson told the woman that the rapist had not attacked in months—but that he was still out there. The policeman admitted that he was getting desperate. He sighed and said, as much to himself as to her, “I’ve been working on this case for a long time.”

She nodded, thanked him, and made plans to move.

On the Friday evening of Memorial Day weekend in 1989, a young man walked up to his girlfriend’s tiny house near Forty-third Street and Avenue C. As he approached, he saw a male stranger leaving the residence. The stranger had light brown hair and was slight of build. Beyond that, there was little else to say of his appearance. Indeed, as the boyfriend would later say, “He was so normal-looking he defied description.”

The stranger tried to hurry past him. The boyfriend grabbed him by the arm. With his free hand, the stranger pointed a gun and then ran off while the boyfriend rushed inside the house. His girlfriend was tied up on the bed. She had been raped.

Five nights later, a 21-year-old Greenpeace worker was taken to St. David’s Hospital. She had been raped that night in her Hyde Park home.

About six months later, another 21-year-old woman reported an attempted sexual assault that had occurred in her garage apartment at Fortieth Street and Avenue D.

In each of these three attacks, the victim elected not to press charges. The cases were suspended, the incidents went unnoticed by the press, the police gave no answers, and the neighborhood asked no questions.

Just a few days before 1989 became 1990, a Hyde Park realtor received a call from a young man who wished to see one of her properties, near Shipe Park on Avenue G. The realtor agreed to meet him there.

She arrived a few minutes later and stood in the empty house for some time. Then she looked out the window and saw a young man, presumably the one who had called. He was trying to get in the back door. He had apparently arrived on foot and had come through the alleyway. She thought that was odd.

He went around to the front, and she let him in. He was thin and of average height, with slightly wavy brown hair. His handshake was limp, and he continued to look down at the ground, seemingly uninterested in the details of the house he claimed he was interested in buying.

As realtors often do, she tried to draw him out of his shell by asking him questions. He said that he lived nearby but that he hadn’t lived in Austin for very long. He said that he studied math at UT. The realtor saw an opening to loosen him up. “A math whiz,” she observed. “You’re like my daughter. She’s a little shy around people, but she’s great with computers.”

His reaction to this was strange. He told her that his mother had never taught him how to deal with people, particularly women. His relationships with women were not good, he said. And for this he blamed his mother. His tone was dark and hostile.

The realtor fought to contain her fear. She said she was expecting another client momentarily and that he had to leave. Before they parted company, the young man asked her about the garage apartment in back of the house. She refused to show it to him. “It’s being rented,” she said.

She was a nervous wreck when she returned to her office. To one of her associates, she gasped, “Jesus Christ! I think I met the Hyde Park Rapist! Does he even still exist?” Then she called the police.

A few nights later, on January 3, 1990, the young woman who lived in the garage apartment stepped outside and was promptly pushed back in by a man wearing a bandanna over his face and holding a gun in his right hand. He tied her up and gagged her and raped her. Fearing that if she looked at his face he might kill her later, she shut her eyes. This irritated him. He asked her to open her eyes. She would not. The assault lasted forty minutes. Her boyfriend would be by soon—she knew that; so did the rapist.

Perhaps ten minutes after the rapist had disappeared down the alleyway, police officers arrived on the scene. Bloodhounds loped up and down the streets and alleys. Almost instantly, the dogs lost the scent of the Hyde Park Rapist.

And as for the short brunette in the garage apartment, known by some neighbors only for the red sedan she drove, she and the red car were gone the next day and did not return.

It is this way with the victims of the Hyde Park Rapist. The attacks on them are unheard, and their departures are just as inconspicuous. Yet all of them have left Hyde Park, and only a few remain in Austin. When he assaulted them, they feared for their lives. Today they fear that he is watching them still, wherever they might be, and that he will finish the job. The people who assure them otherwise have never been attacked in their own home, in the darkness, tied naked to a bed and dominated so completely. Such people would not understand why, to these women, hell is losing control.

The law student who was raped on July 3, 1987, has gone on with her life. She now works for the attorney general and helps see to it that all varieties of menace are kept in the slammer. What she has come to accept is that one man may elude her—that, in her belief, “he’s not going to be caught unless he screws up.”

He cannot take away her vivaciousness, her self-confidence. “My revenge,” she says, “is not to let him have any further control over me beyond what he exerted that night.”

She admits, however, that the memory of that humiliating invasion still sends her into tailspins of depression. He has given her anger, and she has used it for her own purposes. Yet he has also left her fearing empty houses. After the rape, she bought a house and found three male roommates to move in with her. It wasn’t like her, she knew, but she also knew why she did it. Even so, from time to time, she would be reading in her room, then suddenly hear a roommate’s voice next to her. The terror was physical. She would feel like vomiting.

Three years later, she asked her roommates to move out. “It’s time to do it,” she says over drinks. “But now I’m left with a four-bedroom house. What if I don’t like being alone?”

Her confident voice grows small. “This scares me.”

After a rape, a victim must reclaim herself. It is this way with Hyde Park as well. One hears that effort in the optimistic voice of John Sanford: “We’re going to work with the police, and I think we’re gonna catch this guy and the neighborhood will be even better. That’s my attitude about it. I’m a can-do person. I’m a problem solver. We’re gonna solve this.”

Yet Sanford and his neighbors have finally confronted a problem that cannot be solved by fundraising drives. In the waning months of 1990, four more women, aged 19 to 27, were attacked in their Hyde Park apartments. The modus operandus suggests that the assailant was the Hyde Park Rapist. The police will only say that the cases are still under investigation. Perhaps the women who have left Hyde Park understand better than anyone why Hyde Park must minimize the problem or redefine the problem or run from the problem.

For in the absence of complete control, people must have faith: faith that the violence within our culture will not swallow us up; faith that we can purge our demons. It upsets James Allman to hear fellow neighborhood association members urge that the issue of the Hyde Park Rapist be downplayed lest real estate values plummet. “It’s far more important,” he says, “to prevent the kind of wreckage that this person is leaving in his wake. If people are concerned about their real estate value, I think they can invest in another coat of paint.”

Yet he adds, “Over the long haul, the things that catch criminals are the random contacts of basic human decency, so that when an attack is launched against the individual, he’s attacking the entire network. The fuller her social life, the greater the chance that the social network will interrupt or arrest this person.”

He says this in his garage apartment, where he labors alone as an architect. Allman is filled with the human decency in which he places so much faith. Yet he does not take into account that a young nurse once lived in a garage apartment almost identical to this one—that the resident, like Allman, enjoyed both a full social life and her moments of solitude. Unlike Allman, the resident was a female, and the Hyde Park Rapist seized her solitude from her.

Now she tries to forget, and so does the Hyde Park social network.

From the Hyde Park Bar and Grill, a stylish 24-year-old woman steps out into the light. She squints at her old neighborhood, noting the things that have changed, the things that have stayed the same. She loved this place and spent many happy years here. But there are other nice neighborhoods, like the one she inhabits just east of the freeway. Life goes on after a move, just as life went on for her after she fought off the Hyde Park Rapist on November 11, 1988.

Her wrists have long since healed from the bruises, and she says that she has overcome most of the bruising fear. She lives alone as she once did, though she will not let strangers inside and will never again leave her door open in hopes of hearing the rustling of raccoons.

A gentle breeze tosses a few strands of her hair into her eyes; she pushes them back and continues to gaze. “He doesn’t seem real to me,” she says, half smiling, thinking her words absurd. “It’s as if he’s just a ghost that sort of lingers here.”

Then she shakes hands, says good-bye, and hops into her car. It will take her perhaps six minutes to drive home. In that span of time, another American woman will be raped. But not in Hyde Park—not then, not today, and not for the rest of the week. He remains among them, but he does not share the crisis that is his life, and the week is blissful.

Robert Draper is a freelance writer who lives in Austin.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime

- Austin