On the day he thought he would lose his job, Ed Jones sat with his wife in the kitchen of their mobile home. It was shortly after dawn on Friday the thirteenth of May. Jones was a roughneck for the Stewart Well Service Company of Manvel, a small, family-owned company based in a small country town 25 miles south of Houston. Jones himself lived in Alvin, half a dozen miles east of Manvel and closer to the gas field where he was due for work at 7 a.m. As the morning traffic thickened on Loop 35, the freeway that bypassed Alvin and swept within yards of the trailer park, Jones waited impatiently for his ride to the field. The white Ford pickup carrying the four other members of his crew was due at 6:30, but at 6:45 Jones was still swirling coffee in his cup and studying the oncoming vehicles.

No one would really notice if the crew reached the field late. The “company man”—the gas company’s representative on the spot—usually didn’t show up until after eight. Then he would park his sedan fifty yards from the rig and watch from inside the car, steam rising from his coffee cup. But Jones believed that a good crew had to keep up its discipline even if nobody was watching. That was the kind of character he had looked for in roughnecks, back when he had an office job.

It was only five months earlier that Ed Jones had sat behind a desk as personnel manager for Stewart Well Service. From his office—a trailer rolled into the tool shop at the Stewart yard—he deployed the human resources of the firm. Constantly receiving reports and issuing instructions over the telephone and the two-way radio, he dispatched replacements when roughnecks were absent or injured. He sized up the gruff, muscular men who presented themselves for oil field work and decided which ones were up to the job.

As these potential roughnecks answered Jones’s questions, they had before them an illustration of the opportunities the oil fields might offer. Less than a year before he became personnel manager, Jones himself had hired on as a “worm,” dead bottom of the roughneck hierarchy. To ascend from the rawest, least-skilled laboring position to the managerial class in ten months was exceptional, even during the oil field boom of the late seventies. Not every laborer possessed Jones’s fierce determination to move ahead, but those who did could see in him the heights to which a workingman might conceivably rise. The range of possible ambition seemed so much broader in the oil business than in other industries—or at least it did until the price of oil began to fall.

Well service companies perform a variety of repair and maintenance tasks on oil and gas wells. Their customers are oil and gas producers, such as Amoco or Mobil, or large independents like Superior. When the market for oil went down in 1982, so did demand for well services, as oil companies postponed all but urgent maintenance. It was this change that had taken Ed Jones from the office back to the oil field where he had begun. Stewart Well Service had risen and fallen too—from unprecedented prosperity to potential bankruptcy. It was in bankruptcy court, on May 13, that a judge would determine whether company assets should be liquidated to satisfy a major creditor.

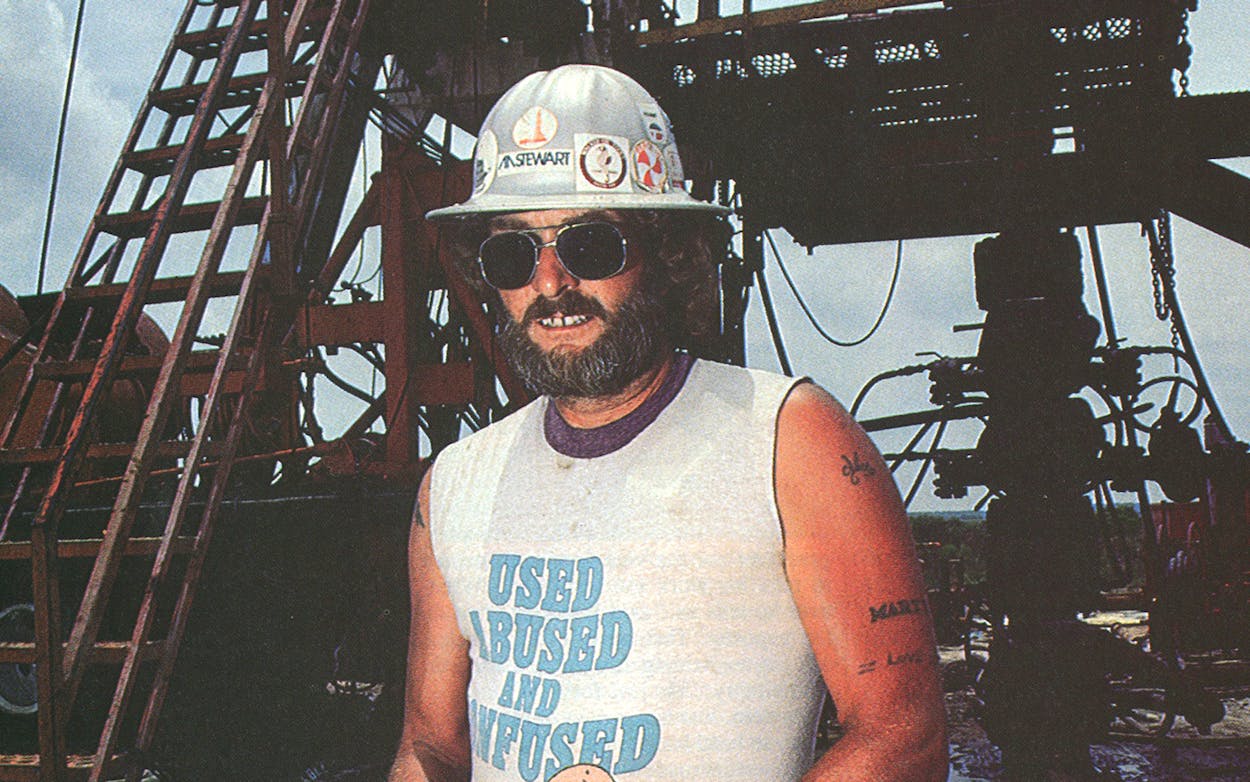

Ed Jones was a medium-height man with a dark beard and brown hair that hung below his ears. He wore an orange T-shirt with the sleeves cut off, revealing the USMC tattoo on his right forearm and other names and slogans elsewhere on his arms. Jones was one month away from his fortieth birthday, but he was in better physical shape than he’d been in for years. Field work had given his shoulders and upper arms a chiseled thickness and removed a roll of flesh from around his middle. As he waited for his ride to the oil patch, one black work boot resting across the other, he had a roguish, dashing air.

While Jones drummed his fingers on his lunch pail, his wife, Jacqueline Sue, bustled to the back of the trailer. She was a thin, sharply pretty woman of thirty, with dark, tightly curled hair and wide-set eyes. She wore blue jeans and a tank top. A few minutes later she emerged with two children. Geri, two, was wrapped in a blanket in her mother’s arms, while six-year-old Michele padded behind her in a nightgown, rubbing her eyes. Jackie Jones’s shift at Diversified Ceramics in Alvin, where she worked as a “wiper” taking excess glaze off custard bowls and ramekins, began at seven. Before her ride arrived, she had to get the kids to their baby-sitter’s trailer at the other end of the park.

”That’s the worst thing about Jackie’s working again,” Ed Jones said as the rest of his family left the trailer, “having to get the kids moving before they’re even awake.” A moment later the Ford pickup roared up the gravel path through the middle of the trailer park. Ed Jones was off to the fields.

For a brief moment in their lives, Ed and Jackie Jones straddled the line between two classes. They had come from Indiana to Texas, working-class refugees from a declining region. Within five years, Ed Jones was earning the income and carrying the responsibility of a professional manager, although by background and bearing he was still a man of the working class.

The progression from one class to another does not often occur within a single generation. The immigrant housekeepers and merchants hoard their money so their children can go to college. The factory worker saves his hourly wage in hopes that his children will rise to salaried jobs. The exceptions, the rags-to-riches stories, usually involve a speculative, boom industry: real estate, show business, professional sports. And so it was here: it was the speculative, booming oil business that enabled Ed and Jackie Jones to cross the class line within a few years.

When the boom faded, the Joneses were pushed back across the line. But while their income changed, their ambitions did not. The friends they had left behind in Indiana seemed resigned to a certain station in life, powerless against the fates that closed their factories and made their cities die. Ed Jones, for the moment another of fate’s victims, feels anything but powerless. If his company closes, if his whole industry stagnates, he will look for other spheres in which to prevail. Because Texas has opened opportunities to the likes of him, it is far better prepared to survive the end of its oil boom than the Midwest was prepared for the demise of steel and cars.

The Marine, The Cop, The Hell Raiser

Ed Jones was not always the disciplined, determined man he is today. He was born in 1943 in New Castle, Indiana, the son of a combat Marine who was killed at Okinawa two days after his son’s second birthday. Jones’ mother, Sadie, was left to raise four children, of whom Ed was number three. After the war she married Elwood Groce, a local man who stayed for one postwar hitch in the Army and then came back to New Castle to work in the plants. Groce, a man who adored children, told the Jones youngsters that he could never replace their daddy, but he would love them like his own. Then he and Sadie had five more children.

Ed Jones is intelligent, but he was no student. He was a hell raiser in school, a favorite with the girls. At sixteen he quit school to work on demolition crews. With his lost, heroic father’s example before him, he dreamed of becoming a Marine, which he was from 1962 to 1966.

When he got out of the service, Jones returned to New Castle and to the life of a machine-shop worker. He married and started a family, which would eventually include three children.

After two years in the machine shop, Jones heard of an opportunity, an opening on a local police force. He applied for the job and was accepted. For the next six and a half years, first in Cambridge City and then in Hagerstown, Jones was a well-liked and respected policeman who could never really go off duty, since in those small towns, everyone knew who he was.

His only problems were domestic: his marriage soured. No one in the family will volunteer details, but something happened between Jones and his wife, something bad, and after it happened, he was dismissed from the Hagerstown police force. Ed Jones had to sit and think about what his options were.

New Castle was then a town of some 21,000 people, a county seat and minor trading center for the farming region of eastern Indiana that lies between Indianapolis and Dayton, Ohio. The surrounding landscape had a backcountry, unmodernized look. Where the land had not been cleared for farming, it supported graceful stands of sycamore and buckeye. In addition to farming, the people worked in factories, most of them tied to the great automobile empire of Detroit. New Castle had a Chrysler parts plant and also a Perfect Circle factory (now owned by the Dana Corporation), which produced piston rings. There was another Perfect Circle plant in Hagerstown, a dozen miles away.

Jones had little prospect of returning to police work anywhere in the area, nor was there much chance of his latching on in one of the factories, since even then the auto industry was starting to have its troubles. He wound up tending bar in Hagerstown, where he worked with Jackie McAllister.

Jackie’s family had lived in Hagerstown for generations; her father was a supervisor at Perfect Circle. She had been married for the first time at age fifteen, had two children, and was divorced. She had gone through a second marriage and was in the middle of a divorce by the time she met Ed.

As they spent more and more time together, they felt more and more hemmed in. Again without offering details, those who knew Ed Jones in Indiana say it became intolerable for him to live anywhere in the vicinity of his first wife, who had custody of their children. “Problems with ex-families,” Jackie later offered as her terse explanation of why they had left. “Too many people wanting to get into our personal lives.”

On the Fourth of July, 1976, Ed and Jackie threw what they could in the back of a 1970 Pontiac and hit the road to Texas. He had $500 in his wallet; she was pregnant with their first child.

The 24-Hour Shift

They first found work in Houston, though not in the oil industry. Ed became a security guard at Astroworld at $4.50 an hour, and Jackie later drove a private tour bus. By the end of their third year in Texas, Jones had been promoted to assistant security manager and Jackie was pregnant again. But he was unhappy with the pay at Astroworld. He had what he calls “a disagreement with my employer, and then I took a couple of weeks off.”

When he started looking for a new job, Jones thought of Lee Murray, an ex-Marine he had met in Houston. Murray had spent twenty years with the Marines; he had enlisted out of Panola Junior College in Carthage, Texas, after finding that he didn’t have the sizzle to make it as a pitcher in the big leagues. At the tail end of his military career he had been in charge of recruiting and public relations for the Marine Corps in the Houston area. He placed great weight on a military background, especially the Marines, in judging other men. So he was happy to hear from Jones when Jones began his job search.

By this time Murray was doing his recruiting for Stewart Well Service. He asked Jones what he knew about the oil drilling business. “I’ve never tried it in my life,” Jones said. “But if you give me a chance, I’ll do a good job for you, and if I don’t, you can run me off.”

Murray did not make a job offer on the spot. He told Jones to fill out an application and advised him to keep hunting. But Jones got himself a hard hat and a pair of steel-toed boots anyway. He was, therefore, prepared to make his own good luck when Murray called him one Sunday afternoon and asked if he would be ready to go out on a rig that night at seven. Jones had been working all day on a friend’s truck, but he told himself that if he said no, Murray would find somebody else. He went to the rig and worked through the night.

At seven-thirty the next morning he was back at home when the phone rang again: could he come back out? A day crew had walked off—in those boom times, it was no rare event—and Murray needed a replacement. Jones worked from eight until noon then returned for the all-night shift at seven. Thus began Ed Jones’s meteoric rise through the ranks of the well service business.

The Worm Starts His Climb

Considered conceptually, the work of a well service company like Stewart is straightforward and simple. A completion crew prepares a well for production after a drilling crew (which uses a more expensive piece of machinery and works for a different company) has drilled the initial hole. Well service crews also do workover projects, repairing and servicing wells that are already producing gas or oil.

When considered in their physical reality, the rigs are notable mainly for their high level of potential danger and the brute strength they demand of their crews. On a typical workover project, the crew might face the assignment of pulling out 2,500 to 13,000 feet of production pipe, through which oil or gas normally flow, and placing it with work pipe. Once the work pipe is in place, the crew sends down whatever machinery may be necessary. It then hauls up the work pipe and sends the production pipe back down. Sometimes the whole process must be repeated three or four times, if work is being done at different depths.

The pipe is laid down and taken up in 30-foot to 32-foot sections, which weigh about two hundred pounds apiece. Workover rigs include the draw works, a gigantic winch that lifts and lowers the pipe into position for the blocks. “I weigh one-seventy,” Ed Jones said one evening after a day in the oil field. “Sometimes I push a wrench on that rig and it won’t move. There’s a guy out there who weighs two-seventy. When he pushes it, it moves.”

If the roughnecks who are connecting and disconnecting pipe let their attention wander, they can end up with missing fingers. If the man operating the draw works forgets what he is doing, he can kill everyone else on the crew. Each man’s survival depends on his partners’ diligence.

Jones did not come to the job with extraordinary physical advantages. By the standards of the oil fields, he was not particularly big. He was also 36 years old, “a little late to be starting out in the roughneck life. I hadn’t done that kind of physical labor for ten years.”

What he had was the willingness to adopt the physical and mental discipline that oil field work demanded. Jones found that a man could survive if he followed instructions, that he could get ahead if he showed extra initiative, and that the opportunities would be his if he showed up and was there to seize them. He soon made his way up the distinct hierarchy of the well service crew, which runs from worm at the bottom to tool pusher at the top. Worm, of course, is where he started.

The worm—or threshold employee, as he is known to the mealymouths of the federal safety agencies—is the go-fer of the crew, the man who fills in for the chores no one else wants to do. He has a special place on the drilling platform, known as worm’s corner, where he watches and learns what he is supposed to do. He might straddle the fuel tank and hand-pump extra diesel to the rig, dismounting to find himself black with grease. “Whenever the dirtiest jobs come up, that’s you,” Ed Jones said of his life as worm. “You find out real quick that you don’t want to be the worm. You drive yourself to be lead floor hand.”

There are normally two floor hands on a rig. They work above the ground on a metal-grid platform suspended from the workover rig. Professionally, they are elevated by their responsibility for specific tasks and specific pieces of machinery. When pipe is being laid down or taken up, the floor hands stand on either side of the column of pipe. The lead floor hand catches the bottom of each length of pipe as it descends, swinging, from the pulley overhead. He then connects it to the length sticking out of the ground and operates the “tongs,” a tightening device that ensures the connection. The other floor hand helps wrestle the swinging pipe into position. From his side of the drilling floor, he quickly connects a metal “elevator” to the next length of pipe and rushes to get his hand out of the way before the winch starts lifting the pipe overhead and dropping it into position.

Floor hands have an inherently more dangerous job than worms. But they also make more money—around $7 an hour, compared to the $5.35 standard starting pay for worms—and have more prestige.

Ed Jones was determined to take the step up. “You can stay a worm your whole life, unless you want to take the initiative,” he says. “You might clean the hand tools when there’s slack time, instead of laying down. If you’re willing to do your own work and ten percent more, then there’s no doubt you can get ahead.”

As it happened, Jones’s tenure as worm lasted just one day. On his second day at work, there was an opening for lead floor hand, which he seized. He began building a reputation as a man who would be there when the company called, who wasn’t afraid to “get right next to it and get all nasty.”

For Ed Jones, the next step was operator, or driller, the man who raises and lowers the pipe lengths several hundred times a day. The operator stands at the controls of a winch that can lift 275,000 pounds; his pressure on the brake lever is the only thing that keeps a massive pulley block, itself 8,000 pounds of steel, from smashing into the floor hands and killing or maiming them, instead of halting, as it is supposed to, several feet above their heads. He opens and closes the “slips,” wedges that support the weight of the thousands of feet of pipe reaching into the ground. “When you take on that job, you’re taking on responsibility for the rig and for three other lives,” Jones says.

A few months after Jones became lead floor hand, a driller got a bad ear infection and couldn’t work. His replacement didn’t show up. Jones’s opportunity had come. He stepped to the controls and began to operate the rig. “I took the initiative, and my point was made that day.”

Up to that time, Ed Jones’s rise might have been taken as testimony to the oil field’s extraordinary openness and indifference to credentials. With no experience in the business, no contacts other than his friendship with Lee Murray, he had been given an opportunity and had shown he could perform. Yet suddenly he ran afoul of the special hierarchy of the oil field. Before a man can move from lead floor hand to operator, he is supposed to spend time as a derrick hand, working at the top of the derrick when the rig is pulling pipe out of the ground. The slogan for this progression is, “From the ground to the crown and back down.” Jones had not worked the derrick, and therefore the supervisor in that field did not want him operating the rig.

A week later, after Jones had returned to his status as floor hand, his second chance arrived. There was another problem with a driller, and this time Ed Jones was allowed to take the controls. “My total apprentice time by that point was about four hours,” he says. “I said, ‘We’ll just take this slow and easy.’ Everybody else on the crew gave me a chance. They could have sat down and said, ‘No way.’ “

Ed Jones had moved from worm to operator after only four months on a rig.

His exceptionally quick rise was due partly to his own efforts, partly to the times. Roughnecks grew so smug about finding new jobs that they’d walk off their old jobs on a whim. Each one who walked made an opening for a man on the spot, and those were the openings Jones grabbed hold of.

Now there was only one rung left: tool pusher. When he worked his way up to that level, Ed Jones would have completed his mastery of the oil fields.

If a drilling crew resembles a small combat unit in the way its members rely on each other for survival, it is also similar in looking good, or bad, as a unit. If the mixture of personalities is right, the crew will pick up pipe quickly and look good to the oil company, which during the boom was paying $185 an hour or more for its services. If it doesn’t, the company will go shopping for another crew, perhaps from another well service outfit. The responsibility for making the crew click lies with the tool pusher.

Like construction crew chiefs and factory foremen, tool pushers operate in the zone where two layers of society meet. The tool pusher’s main responsibility is to keep the crew members—strong, rough, independent-minded workingmen—in reasonable harmony with one another. At the same time, he is often the well service company’s most effective salesman. The impression a tool pusher makes on company men—the representatives from Amoco or Mobil, who have not had grease on their clothes for many a year—can be the most important factor in determining whether his company gets work. The well service companies all use basically the same equipment and draw on the same labor pool. The difference is the tool pushers. Company men will often specify a certain tool pusher’s crew when they have a job to be done.

Because he was hungry and determined and reliable, and because the times were so good, Ed Jones had put himself in position to become a tool pusher by January 1981, not even a year after he had first gone into the oil fields. But he never got the chance, for at just that moment he was lifted out of the hands-dirty, workingman’s progression altogether. He was invited to join the ranks of the managers.

An Office and Pet Cockatiels

As the oil business kept booming, Stewart Well Service kept expanding. It opened an operations headquarters, which created a new position in personnel. Lee Murray, the man who had hired Ed Jones, thought that Jones, with his military experience, with his spectacular success in the oil field, was the man for the job. “I did not hesitate one minute,” Jones says. “I moved in and took over personnel.”

From that point on, Jones saw life on a different plane. For once, he and Jackie had money. His take-home pay had varied between $300 and $700 a week in the oil fields, depending on whether he worked a normal forty-hour week or was on an around-the-clock rig, where men worked twelve hours a day, seven days a week. In the office his base salary was about $25,000 a year, which put him roughly even with field work. But then there were the bonuses. Six months after he went to the office, he received a bonus check for $3,900, Ed Jones’s share of the year’s profits.

The Joneses bought a second mobile home, in the same park where they lived, and rented it out. They replaced the furniture in their own trailer and fitted it out with modern appliances, tropical fish and pet cockatiels, five TVs and a videocassette recorder. Ed Jones built up his gun collection.

“I still owe money,” he said last fall, when the boom had ended but he still had his office job. “The difference is that I can meet my bills and have money left over and not be in a sweat all the time about where the next payment is going to come from. If we decide to go out, I don’t have to say, ‘We can’t do it right now, because I need to pay this bill.’ “

But it wasn’t simply the money that made the difference in Ed Jones’s life. Had he been intent on maximum earnings, he would have spurned office work and waited for assignment as a tool pusher.

Pushers earned salaries, not hourly wages, and they were eligible for profit-sharing bonuses up to the amount of their annual salaries if they ran profitable rigs. During Jones’s tenure as a manager, one tool pusher qualified for a bonus of $29,999.

Jones seemed willing to defer some financial rewards as part of his full-fledged acceptance of the burdens of the managerial class. He kept his hard hat, coveralls, and steel-toed boots behind the chair in his office, and he was ready to fill in on a rig or work as a temporary tool pusher if a crew came up shorthanded.

But that was mostly an indication of how sweepingly he defined his responsibilities. If a roughneck got in a fight or quit, the problem was Ed’s to solve. “It’s not like a union shop, where if you’re not there nobody misses you,” he said. “If you’re not with the crew, you’re missed.” Jones could never be far from his telephone or from the company’s mobile two-way radios. He wore Stewart Well Service T -shirts and spoke with respect, gratitude, and loyalty about the company. “I’ll do just about anything I can to keep the rigs running and the company making money,” he said.

He refined his sense of the human chemistry of rig crews, the combination of people who could work and fight and drink together. He recognized that Troy Moreland, a 21-year-old roughneck who came from an oil field family and had been working rigs since the age of 17, was ready to be “broken out” as a tool pusher, while others twice his age would never be ready. As roughnecks quit and moved on and new men showed up for work, he constantly shuffled the lineups, intent on keeping the rigs productive.

And Ed Jones saw no reason why his ascent should end. “I’m kind of chasing Mr. Murray,” he said last year. If Lee Murray was promoted, that would open up safety work—and eventually sales, the traditional entree to white-collar status and income. As far as Jones could tell, there were only two real limits to his progress inside the company. One was the Stewart family, which owned and ran the company and would for the foreseeable future. The other was his lack of formal education, which he thought would keep him from certain top sales positions.

His rapid rise had left Jones straddling the working and professional classes. He earned more money than most schoolteachers or state employees, who wore suits to work and valued their educational credentials. Yet he was in an industry that seemed blue-collar almost by definition. He was touchy about that most common obstacle to movement out of the working class—a college education. He liked to point out the many idiocies of college boys when they came face to face with real work, such as on the rigs. (“If you came in here to sign on for a job, I’d have a hard time placing you,” he told me, a college boy, one day. ”I’m just judging by appearances.”) He said that he’d want college to be available as a choice for his children, but he certainly wasn’t going to force it on them. As for himself and his friends, they’d taken their education from the “school of hard knocks.”

Yet Ed Jones, at the crest of his career, would willingly tolerate those tensions if they were the price he paid for having come so far so fast. He was justly proud of his achievements, determined to push ahead. Then the oil business crashed.

Back Down the Ladder

The oil bust hurt everybody in the business, of course, but Stewart was more vulnerable than most. For the previous 45 years of its existence, the company had been run on the classic, conservative principles that came naturally to men tempered by the Depression. E.O. Stewart Sr., who founded the company with his brother during the thirties, had expanded slowly and carefully, adding rigs when he could pay for them, calling on his wife to take care of the books. Stewart drove a Cadillac but dressed modestly; on a typical business day he would wear an inexpensive-looking white shirt and a tan cardigan. He put his earnings back into the firm.

“The business kept growing real steadily until about a couple of years ago,” Stewart said last spring. “Then it went crazy.”

During the boom, no one could see an end to the demand for oil or for workover rigs. The hourly rates for a rig and crew went up; so did wages and overtime. “In those days,” Lee Murray said when the boom had passed, “you stuck to your published price, and they took it—and then you said, ‘Well, maybe we can fit you in three weeks from now.'”

“Everybody loves a profitable business,” E.O. Stewart said—including the companies that make workover rigs. If there was a shortage of rigs, they would make and sell more. And if their customers—the well service companies—lacked the up-front money, what was wrong with credit? After all, the rigs would quickly pay for themselves.

It all made sense during the boom. When company owners (customarily no-nonsense characters who remembered hard times, whether of the thirties or the early seventies) gathered for conventions, there was a new air of ostentation, a competitive display of gold chains and foreign cars. Why not spend the earnings and take on debts when the money kept pouring in?

Some well service companies resisted the temptation. When they had the cash, they bought; until they had it, they held back. They were afraid—as E.O. Stewart had been for so many years—of being overextended with debt. Some of them were lucky and paid off their loans while the boom was still on. The Stewarts thought they’d be lucky too. Through 1981, in the middle of record-breaking profits, they bought five new rigs, at roughly $750,000 apiece, on credit. That brought their total to sixteen, and for a while nearly all of their rigs were busy. The company was making more money than it ever had before.

By the end of 1981 the well service industry as a whole had 86 percent of its rigs at work. By April of this year the rate for the Texas Gulf Coast was 43 percent. For Stewart Well Service, the timing could not have been worse. Had the company bought its new rigs earlier, it might have been able to ride out the tough times; as it was, the company was being dragged down by its debt. In the fall of 1981 the company was constantly running twelve to fifteen rigs in the field. By the summer of 1982 the average had dropped to four or five, and even those that were working weren’t bringing in the money they had once commanded. For the first time in memory, there was such a thing as price competition among the firms. Officials at Stewart spoke bitterly about the tricks their competitors would play: “You’ll have a deal set, and at the last minute they’ll come in and undercut you.”

At one point in 1983, only one Stewart rig was out on a job. Several of the others had gone back to the finance company. The Stewart family had mortgaged nearly everything it owned in an attempt to raise cash and keep the business going. “We figure if we can make it a couple more months, we’ll survive,” E.O. Stewart said early this year. But time was running short. In January the company filed for protection from its creditors under Chapter 11 of the bankruptcy law. One of the main creditors forced a showdown in bankruptcy court, which took place on May 13. In the end the judge gave Stewart six more weeks to come up with a plan for paying its debts.

To the Stewart family, the end of the oil boom meant that every tiling they had built in fifty years might be lost. To Ed Jones, it meant a trip back down the same ladder he had so rapidly climbed.

As times turned bad, Stewart began laying off roughnecks. This was natural from the company’s point of view; everyone thought of roughnecks as born drifters anyway. “We deal with a transient-type population,” Lee Murray said when the big layoffs were beginning. “They’ll be working here for a couple of weeks, and then they’ll hear that a friend is someplace else, and they’ll quit to be with him.” The roughnecks didn’t stay in touch when they left; no one was quite sure what happened to them.

The company was also determined not to lay off its managers, including Ed Jones. “They want to keep a group of key people together so they’ll be ready when things come back,” Jones said in March.

The only way to keep the key people on the payroll was to send them back to the fields. So it was that Ed Jones, who for two years had worried about other men’s schedules and personalities, returned to the rigs.

“I’d Miss the . . . Prestige”

In the early spring of this year, when he’d been in the field a little more than a month, Ed and Jackie Jones were till viewing his return to the blue-collar world almost as a vacation. He slapped his newly hard stomach one evening. “I’ve lost about twelve pounds since I’ve been out there,” he said. (By May he’d lost 20, from 185 to 165.) He had let his hair grow longer and had a wild, scruffy look. “It’s still damned hard work. You’re out there with those eighteen- and twenty-year-old bucks. They’re watching to see, can the old guy make it? You’ve got to show them that you can.” He said he hadn’t forgotten anything about the work. “It’s like riding a bike.”

“I had forgotten something” Jackie said. “How filthy his clothes get.”

Jones found his niche on the crew run by Troy Moreland, the young man he had promoted to tool pusher. Jones was older than the other members of the crew and senior to most in terms of service with Stewart. But the seniority that mattered was within the crew, and he willingly took his place as the new man, doing whatever was required.

“When they first heard I was coming out, they said hell, no,” he said last spring. “They figured after two years in the office I wouldn’t want to carry my load. They found out real quick that I was going to do my share.”

He claimed that he himself was in no hurry to return to office work. “These days I’m paid hourly,” he said, “which means, when I’m home, I’m home. The difference is, I know what I have to do. I have to get out there at seven and fight that iron for the next ten hours. At five o’clock, nine out of ten times I am home. I don’t have to sit there at five and say, ‘Where the hell am I gonna get a crew for tomorrow?’ “

“I still have my radio ,” he said, pointing to the radio system that had once linked him to the office. “In the evening I can sit here and listen to them. Usually at seven you’ll still hear them in the office worrying about a crew.”

Why, then, plan on anything but the field?

“That’s what I want to know,” Jackie said, with a quick look at her husband.

At this, Ed shifted in his seat and said, “If I didn’t get back to the office, I wouldn’t have to go out with the company men. You get one who likes to party, and you’re out till two or three a.m. But if I didn’t go back there, I’d miss the . . . prestige, the opportunities to move up the ladder.”

As the spring wore on and the company moved closer to the brink, the merits of office versus field became academic. There was little work of any kind. One week Ed Jones had seventeen hours on the job. Jackie started at the ceramics factory, at piecework rates.

For a while there was the prospect of a savior. A larger, more diversified company, with the wherewithal to absorb Stewart’s debt, was negotiating for a takeover. “For the Stewarts, I hope they make it,” said Jones, who never spoke disloyally of his employers. Yet a bigger company would have more room at the top, would let Jones continue to climb toward a secure income, a professional identity. He had proved himself fit for this ascent; was a mere oil glut to arrest it? If he thought he would be trapped in place, he might as well be back at the machine shop.

But the takeover deal fell through. Two days before its appointment in bankruptcy court, the company suddenly shut down its yard in Bryan and returned the equipment to Marvel. Thanks to the judge, the company had six weeks of grace. After that, no one knew what to expect.

The Green, Green Grass of Home

During Ed Jones’s flight toward the top at Stewart, his history stood as a reproach to those who sat back home in Indiana and waited for things to pick up at Perfect Circle. They had no one but themselves to blame, when such rich opportunity lay to the south. Now that Jones has been brought back to earth, it might seem that the others knew what they were doing when they decided to stay put. Does Ed Jones’s experience illustrate anything beyond luck’s special blessings, the specific hungers he wanted to feed? I went back to Indiana in an attempt to find out.

Ed Jones’s stepfather, Elwood Groce, conducted a driving tour of the town Jones left behind. “See those big buildings over there, the brick ones? They used to belong to Sears, before it pulled out … That used to be the railroad station. That was a lumberyard. That used to be the dairy.”

Groce, who raised nine children and stepchildren by holding two or three factory jobs at once, is now a stout, slow-moving man, off work since 1979, when his heart went bad. He lives in a modest white house, which his children built for him, near the Perfect Circle factory in New Castle. There he tends his strawberries and peonies and occasionally has one of his grandchildren in for the day, breaking their routine at Kiddie Kare. His wife, Sadie, Ed Jones’s mother, has worked for ten years in the warehouse of a local discount chain.

To the outsider, this part of central Indiana is a landscape of used-to-bes. The economy of the region was fatally dependent on the automobile: more precisely and unfortunately, on the largest models Detroit made. From the Chrysler plant in New Castle come parts for the biggest Chryslers. People speak bravely about resurgent demand for big cars, but of the 2,900 workers Chrysler employed at its peak, 2,100 have been laid off. According to the local UAW official, perhaps 150 have been called back in the last two years.

On the road into town the visitor encounters a billboard with a larger-than-life photo of a lanky, smiling young man. He is Steve Alford of New Castle Chrysler High School, who was chosen not only Indiana’s Mr. Basketball but also Mr. Basketball USA this year. Next fall he will attend Indiana University, where New Castle’s other Mr. Basketball, Kent Benson, once led the Hoosiers to a national championship. He is the principal indication of hope for the future in this declining town.

The families that Ed and Jackie Jones left behind are willing to acknowledge, in principle, that opportunity lies elsewhere. “We like Texas!” wrote Jackie’s father, Gerarld McAllister, on a child’s erasable slate, when asked about how he felt about their move. (He recently had a throat operation that left him temporarily without the use of his larynx.) Like the Groces, the McAllisters seem vaguely proud of the gumption their children displayed in moving south, even though the immediate cause was a messy family quarrel that drove Ed Jones from the police force—and even though they themselves would never leave.

“If we were young, I don’t think we’d stay,” said Sadie Groce, a soft-spoken, dark-haired woman, wearing her short red warehouse jacket during her lunch break. “But I just don’t feel like moving now.”

One force that keeps people in town is simple inertia. Another is the depressed real estate market, which makes it nearly impossible to recover a lifetime’s investment in a house. But overshadowing the practical considerations are the bonds of family. They seem to be the main reason that people old and young hate to leave a place like New Castle.

Elwood Groce was one of nineteen children in his family. Sixteen of his brothers and sisters are still living, and most of them live nearby. Gerald McAllister worked for 46 years at the Perfect Circle plant in Hagerstown (“and was never laid off a day”); his roots are here.

“I love this town,” he rasped out, laying down his slate.

“Most of the people he used to work with still live around here,” his wife, Ramona, explained. “People who live in this town just like the feel of it.

“All of my family is buried in that cemetery, ” she said, gesturing out the window of their comfortable house and past the village green, “my parents, my grandparents. They were farmers, mainly.”

When people must leave, it is taken for granted that they live for the day they can return. One of Ed Jones’s brothers was transferred to Texas before Ed and Jackie moved there; the family history recounts his efforts, so far unsuccessful, to get back home. One of Jackie’s brothers returned to Indiana after traveling throughout a twenty-year Air Force career. (The other, who also lives in the area, was recently inducted into the Squaredance Callers’ Hall of Fame.) The UAW local can’t keep track of everyone who has moved away, but its officials can tick off name after name of those who have come back, having found frustration everywhere else.

Seen from a certain perspective, these small, close-knit towns sustain the qualities that a large part of the nation most grievously lacks. In many places the ties of family often seem too loose, not too confining. At every level of American society, divorce and cultural changes have made families less sturdy than they were a generation ago. In an age when parents’ commitment to their children appears to be eroding, the patience and sacrifice with which Elwood and Sadie Groce raised nine children cannot be sufficiently praised.

It is perhaps in recognition of those values that so many people are now looking for ways to preserve communities like New Castle, even though their economic base is gone. Perhaps tariffs will give new life to the steel mills so that the families of Homestead and Gary can stay together and not be forced to move to Texas. Perhaps a federal redevelopment bank will steer new investment to Flint and Lorain. Perhaps new approaches to worker ownership will let Youngstown’s mills, and its families, survive.

However understandable this impulse is, however much everyone might wish that the steel mills and the auto works were as flush as in the fifties, is preserving New Castle or Hagerstown —or Flint—the right object of the nation’s policies? Is it the right moral to draw from the tale of two of Indiana’s children, moved to Texas?

If the older industrial centers can be saved by better management, improved products, a more cooperative atmosphere in the working place—in short, by once again excelling in the market—then their rebirth will be widely celebrated. If they are being artificially hampered by public policies—as Caterpillar was by the embargo on sales for the Soviet gas pipeline—then the government has an obligation to make them whole.

But what if even that is not enough? What if it takes tariffs, government loan guarantees, other distortions of the free market, to spare any more of New Castle’s residents the need to move?

Sophisticates will argue that there is no longer such a thing as the free market. If the government is not propping up Youngstown through “trigger prices” for steel, it is subsidizing Los Angeles and Fort Worth with defense contracts. Still, the danger of today’s emphasis on preservation is that it will overlook the large part of the nation’s economic history that has been written by the likes of Ed and Jackie Jones: people who moved someplace else, adapted, and prevailed. Newsweek, for example, recently published an eloquent cover story on the “human cost of the collapse of industrial America.” It quoted workers, many in their twenties, who felt betrayed by the decline of autos and steel. Nowhere did it raise the question, Why don’t they move?

The question inevitably sounds smug and heartless. But when economies are changing, as ours is, we must choose among different kinds of pain. One is the pain of adaptation; our willingness to accept it has historically set this nation apart from others. The webs of family and tradition that bind people to Indiana or Michigan were all established by people who moved there from someplace else. Elwood Groce’s family moved to Indiana from Kentucky. Jackie Jones’s great grandparents came across the sea from Ireland. Other cultures, notably England’s, have avoided this kind of pain at the cost of another. They have tried to preserve their New Castles. The English will not be expected to move. They are shielded against all risk of change, except for collective economic decline.

The lesser cruelty of the “why don’t they move” approach is clearer when you consider things from Ed Jones’s perspective. He is rightly proud of his achievements. He would probably laugh at the idea of his being, say, a lawyer instead of a workingman, yet at his peak in the oil field he was earning about half as much as lawyers in their mid-twenties make at Wall Street law firms. With his perseverance and his ability, he could have been one of them, had he been raised in an environment that encouraged “merit” as displayed in the classroom and on Scholastic Aptitude Tests, not with fists or cars or in the Marines. No society has been free of these class barriers, yet their potential destructiveness is largely defused when there are opportunities for people to change their fortune, as there were for Ed and Jackie Jones. How many new opportunities are created when a struggling factory is kept afloat for another year or two?

There is, of course, a comeback to this point, which Ed Jones’s own story suggests. When his fortunes rose, it was because of an oil boom. Now he is back to his hourly wage and his struggle to make ends meet. What good is migrating if there is no boom?

The notion of boom may obscure the force that really drew people like the Joneses to Texas. “Boom” suggests a gold rush, a momentary frenzy that builds no lasting economic base. With the wisdom of hindsight, we may come to see the Persian Gulf states as victims of this kind of boom. When the flow of riches to Arabia ends, as it eventually must, it may seem to have sunk into the sand, leaving nothing more substantial than the gold rush left in the Sierras, than the tin boom left in the Andes.

But there is a different parallel that may prove more instructive. During World War II, Southern California had its own boom, based on aircraft construction. When the war was over, so was the boom—but not the economic energy of Los Angeles. The people who had come to put rivets in B-25’s and P-51’s stayed to build houses and teach school and repair air conditioners and be policemen and sell cars. There was no one replacement for the jobs lost in the aircraft industry; there were tens of thousands of individual adaptations.

The passing of the Texas oil boom might make Houston like Detroit. But if adaptation and the chance for advancement were more important than oil in drawing the thousands of Ed and Jackie Joneses here in the first place, the presence of people like these two is precisely what will enable the state to prosper.

Even as his company faced bankruptcy, Ed Jones had found another opportunity. He and the other members of Troy Moreland’s crew had received a standing offer from a larger, healthier well service company. As long as Stewart Well Service kept afloat, its rival would not steal the crew—and the crew, still loyal, would not jump ship. But if the Stewarts had been closed down that Friday in bankruptcy court, Ed Jones could have started on Monday with the other firm. In this company there was the possibility of a management position, a chance at sales, the opportunity to step up.

“If you do your job right,” Ed Jones said, as he considered his prospects, “you will get ahead.”