The most infamous phone call in recent Texas history came on the afternoon of September 25, 2007, when, at 4:45, Ed Marty, the general counsel of the Court of Criminal Appeals, dialed Sharon Keller, the court’s presiding judge. Both were in Austin; he was at the courthouse and she had gone home earlier to meet a repairman. One hundred and forty miles away, at the Walls Unit, in Huntsville, Michael Richard (pronounced “Ree-shard”) sat in a cell adjacent to the execution chamber. He was scheduled to die that evening for a murder he’d committed in 1986. The CCA, the state’s highest criminal court and the final arbiter in all death penalty cases, was waiting for his last appeal.

But Marty had a question for Keller. It seemed that Richard’s attorneys were having some computer problems that were preventing them from getting their motion for a stay filed before the clerk’s office closed, at 5. They wanted to know if they could deliver it after-hours—5:15, 5:30 at the latest. Keller, who has been on the CCA since 1994 and the presiding judge since 2000, listened to Marty’s question. Under her leadership the court has been one of the more conservative in the country, developing a reputation, especially on the left, for rubber-stamping death sentences. Her reply would cement this: “We close at five.”

Keller’s statement was relayed to Richard’s attorneys, who were unable to meet the deadline. Just over three hours later, Richard was put to death. And that might have been the end of the matter, just another execution in Texas, number 405 since the reinstatement of capital punishment in 1982. But September 25 was no ordinary day. That morning the U.S. Supreme Court had decided to examine the constitutionality of the three-drug cocktail used in lethal injections, essentially putting a moratorium on executions that would last for six and a half months. Because of that decision, CCA judges and staff had braced themselves for an appeal from Richard’s attorneys, one they had been told was coming. Three judges were even waiting at the courthouse for it. One of them, Cheryl Johnson, was the designated duty judge, who, according to the court’s execution-day procedures, was in charge of the CCA’s response. But she was not informed of the phone call that afternoon between Keller and Marty.

In fact, Johnson found out about the conversation from a newspaper account four days later. She was furious, and her fellow judges were shocked. It wasn’t long before outraged lawyers and judges were signing petitions demanding that Keller be disciplined by the Commission on Judicial Conduct, a state watchdog group that has the authority to reprimand judges and recommend their removal from the bench. “I have never seen such a unanimous response from the legal profession,” said lawyer Broadus Spivey, a former president of the State Bar of Texas. The Dallas Morning News called Keller’s decision “a breathtakingly petty act [that] evinced a relish for death that makes the blood of decent people run cold.” Texas Monthly announced, “It is time for Sharon Keller to go.” It seemed that Keller, who had been so gung ho for so long about so many executions, had been caught closing the door on a dying man’s last request.

The CJC typically finds itself probing allegations of relatively minor infractions, such as sexual harassment or obscene language by justices of the peace. But in June 2008, it began to question a dozen of the players in the Richard drama, including Keller. In February of this year the CJC announced formal proceedings against her, making Keller the highest-ranking judge ever to be investigated by the group. The main charge was that Keller’s “failure to follow the CCA’s execution-day procedures” violated the Texas constitution (which states that a judge must not exhibit “willful or persistent conduct that is clearly inconsistent with the proper performance of his duties or casts public discredit upon the judiciary”) and the Code of Judicial Conduct (“a judge shall comply with the law and should act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary”).

The New York Times called for Keller’s removal, as did a group of 24 judicial ethics experts from all over the country. The Legislature joined in the fray when Lon Burnam, a liberal Democrat from Fort Worth, filed a resolution to consider impeaching Keller. Texas hasn’t impeached a judge since 1975, but at an April legislative committee hearing, six lawyers and one former appellate judge spoke in favor of it. “If those reports are accurate,” said defense attorney and legal ethics expert Charles Herring, “Sharon Keller was personally responsible for killing a man on a day when he should not have died.”

Keller—long mocked by defense lawyers, judges, and state legislators as “Sharon Killer”—has brought negative publicity to the CCA before, but nothing like this. It will get worse when the trial begins, on August 17, in the San Antonio courtroom of district judge (and former CCA judge) David Berchelmann Jr. “It’s going to be a donnybrook,” said Cathy Cochran, one of Keller’s brethren on the CCA. Judge will testify against judge. The shroud of secrecy will be lifted—and not only from the court. Keller has been one of the more mysterious judges on the bench, a modest, private person not given to publicity (she declined to be interviewed for this story) who lets her conservative decisions do her talking. “It’s easy for others to demonize her,” said Jim Bethke, the director of the Task Force on Indigent Defense, which Keller chairs. “But she’s a very decent, conscientious person.”

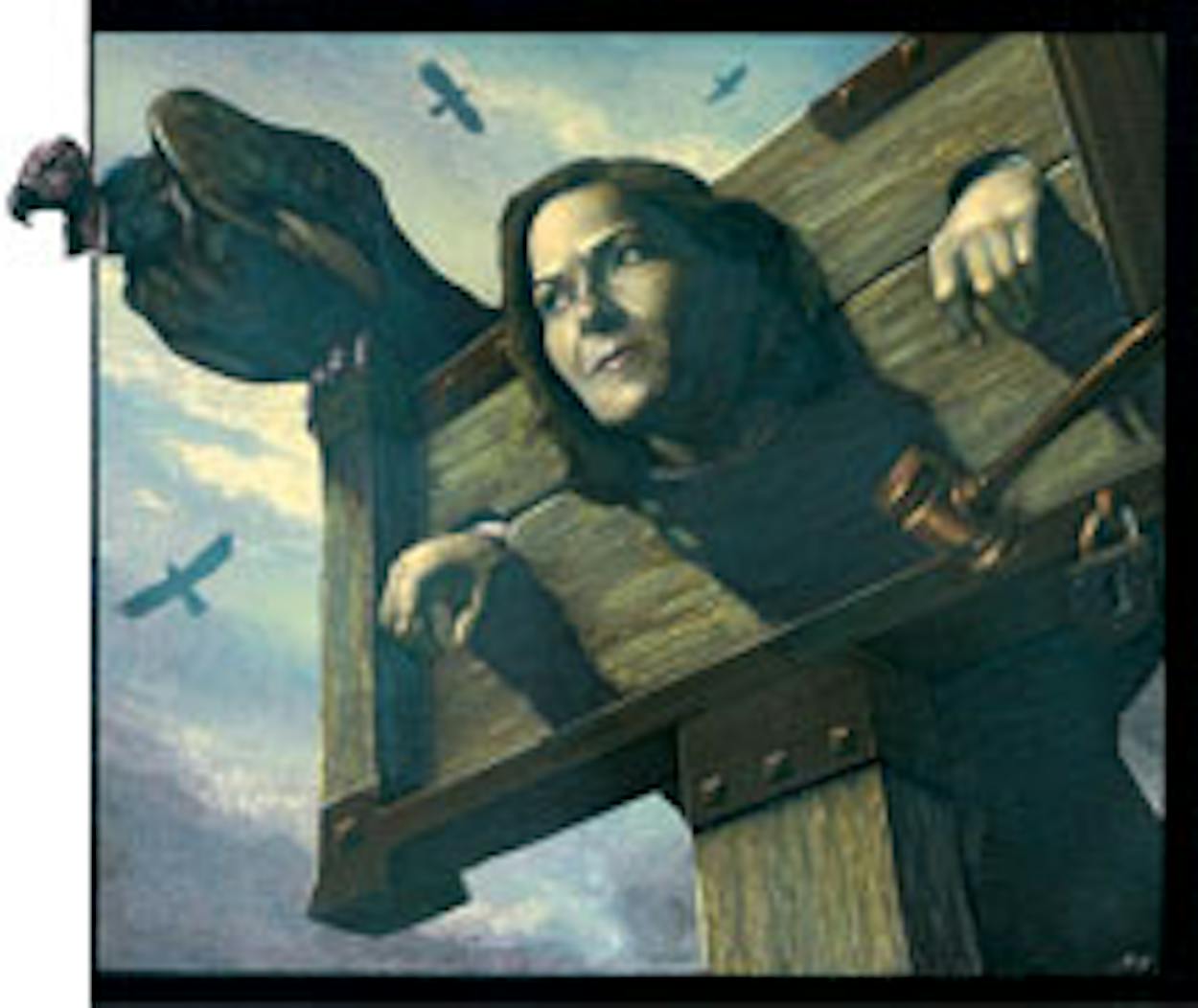

I had a chance to see her in action with the task force on June 10, at a meeting held in the CCA courtroom. Keller was stylish and poised, leading a group of a dozen judges, lawyers, and state legislators, including Democratic representative Pete Gallego. The men wore shades of black, brown, or gray; she had on a canary-yellow skirt, blouse, and jacket. Keller has dark-brown hair and the still-sharp features of a woman who in the past ten years has crossed over from pretty to elegant. Sitting in the middle, she introduced speakers, asked questions, and raised points of order in a soft voice. She seemed unfazed by the legal tempest outside the courtroom—certainly no one inside mentioned the Richard case—and made a couple jokes that brought loud laughter from everyone. She led the session as a modest, small-town mayor might run a city council meeting. “If you asked me about the nicest, kindest elected officials I’ve ever met, Sharon Keller would be on the list,” says Gallego. “But on the death penalty, she’s hard-core. She’s a study in contradictions.”

Keller never set out to be the highest judge on the highest criminal court in Texas. She is something of an accidental jurist, a shy, smart woman who found herself in that powerful center seat through hard work, discipline, and a little luck. Having Jack Keller for a father didn’t hurt her either. A colorful Dallas entrepreneur, “Cactus Jack” found fame and fortune in the all-American industries of fast food, real estate, and oil. In 1950 he started Keller’s, a drive-in selling burgers and beer. Sharon Faye Keller was born three years later, the second of four children. She grew up in Forest Hills, near White Rock Lake. Her father eventually owned three Keller’s drive-ins, and by the seventies the restaurants had become Dallas icons and were making $1 million a year. Cactus Jack’s other investments ultimately made him and his family a small fortune.

Keller spent her childhood at the exclusive private Greenhill School, which she attended from age four to seventeen. Her 1970 senior yearbook photo shows a dreamy, long-haired girl looking past the camera, a blossom peeking out of her hair. But Keller was no flower child. “She was an A student and a member of every sport and club,” remembers a former classmate. The overachiever belonged to the Spanish Club, the French Club, the Latin Club, the International Club, and the Gourmet Club. She played volleyball, basketball, and powder-puff football. She served three years on the student council and two on the yearbook staff. She was crowned homecoming princess. “Nobody had a bad thing to say about her,” says Kevin Madison, now a municipal judge in Lakeway. “She was smart, pretty, sweet, and soft-spoken.”

After graduation, Keller spent a year at the University of Dallas, a conservative Catholic college, but her father talked her into transferring to Rice University, where her sister, Jacque, was enrolled. Rice was not that far from Greenhill, but culturally it was another world. One old friend remembers, “The people who went to Rice were very often nerdy social misfits, people trying on new personas.” Keller did too, falling in with a group who drank and threw wild parties. She was the quietest person of the bunch, says another friend. “She didn’t seek out arguments, though if Sharon felt strongly about something, she let it be known.” After considering physics as a major, Keller took a few philosophy classes, which suited her temperament. “It was basically ultra-rational stuff,” says William D. King, an Austin judge who was a classmate of Keller’s. “Linguistics, logic, lots of rigorous logical discussion.” She still found time to go to Mass every Sunday. “Her commitment to her religion was enormous,” remembers another friend.

According to a profile written for the Dallas Bar Association in 2002 (the only interview about her personal life she’s ever granted), Keller was “uncertain what she wanted to do next. It was her father who suggested law school; he thought it was something she might like.” She was accepted at the Southern Methodist University School of Law and moved back to Dallas. She earned her degree in 1978 and hung out her shingle as a solo practitioner in the twenty-story Campbell Centre. On January 29, 1981, she married a young neurosurgeon named Hunt Batjer Jr. Their son, John Temple Batjer, was born on July 18, but the marriage didn’t work out, and Keller filed for divorce by the year’s end. (She was the second of Batjer’s four wives. Today he is the chairman of the Department of Neurological Surgery at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, in Chicago.) She went to work for her father’s business as a senior executive while she raised her son, whom she enrolled at Greenhill.

In 1987 another Greenhill parent told Keller about an opening in the Dallas County district attorney’s appellate section. She won the job, working there from 1987 to 1994, first as an assistant district attorney, then as a legal researcher. She read the trial record, researched the law, drafted appellate briefs, and argued appeals. Appellate cases are different from those that go before a jury. The state has already won once, and it almost always wins again on appeal. There’s none of the compromise and negotiation with the defense that takes place at trial. As a lawyer told me, “If you don’t spend much time in the courtroom trying cases, you may not develop the skepticism of testimony, such as that of eyewitnesses. At the appellate level, you don’t have to focus on the credibility of the witness. The jury already made that call.”

Keller thrived. “She was very thorough,” says former appellate lawyer John Hagler, “always well prepared, very sharp, a strong advocate.” One of her jobs was to assist trial prosecutors. Dan Hagood, now a Dallas defense lawyer, was in the trial section. “She was the best appellate lawyer in the office,” he remembers. “She would really drill down deep. Most lawyers would say, ‘On the one hand, it could be this, and on the other hand, that.’ But you don’t want that. You want a lawyer who will tell you, ‘It’s this—this is the answer.’ She would find an answer.”

Keller worked for DA John Vance, who, like Henry Wade before him and Bill Hill after, was famous for a high conviction rate (later all three would become infamous for a high convicting-the-innocent rate). In this environment, Keller developed her by-the-book, pro-prosecutor philosophy, confident that the state should win every time. “Her values are based on following rules,” says former CCA research attorney Jani Maselli. “Criminals don’t follow rules, and when you don’t, you get punished.”

In late December 1993, Keller spotted a newspaper clipping on an office bulletin board about CCA judge Chuck Miller’s last-minute decision not to run for reelection. She had never considered running herself until her boss encouraged her. “Vance thought she was an outstanding lawyer,” remembers Hagood. “He suggested it to her.” At that time the CCA was an all-male and mostly Democratic court. Keller dropped the name “Batjer” and ran as a Republican, writing an editorial for the Morning News subtitled, “Don’t end capital punishment.” She described herself as “pro-prosecutor,” explaining to a reporter, “I guess what pro-prosecutor means is seeing legal issues from the perspective of the state instead of the perspective of the defense.” She borrowed $212,800 from her family and herself, outspent her opponent three to one, and won handily—as did almost every Republican on the ticket in 1994, riding the coattails of George W. Bush. A few months earlier, she had been a legal researcher; now she was the first woman on the state’s highest criminal court. A college friend saw her in Austin not long after the election: “I said to her, ‘I didn’t know at Rice that you were a Republican.’ She said, ‘I didn’t know either!’ ”

From the beginning, Keller kept her promise to vote with the state. Appellate courts don’t decide whether the defendant committed a crime; the judges examine whether the trial was fair. Keller and her colleagues almost always thought it was. In 1995 and again in 1996 the court denied relief to two death row inmates, even though it was shown that their court-appointed attorneys had fallen asleep during each of their trials. In 1996 Keller wrote her first major decision, denying relief to a man who had confessed to murdering an El Paso cab driver—even after it was revealed that Juárez police had told him that if he didn’t confess, they would torture his mother and stepfather. Both the prosecutor and the trial judge said that this was dirty pool and the guy deserved a new trial; Keller and the CCA disagreed.

Keller showed up early, worked hard, stayed late, and almost always voted with the conservative bloc, led by presiding judge Mike McCormick, who was impressed with the rookie’s temperament and skills. “She can actually write the King’s English,” he gushed. Frank Maloney, a Democrat who served on the CCA from 1991 to 1996 and is now a visiting judge, recalls, “She was very conservative, and she followed the lead of McCormick, who was extremely conservative.” McCormick began to share some of his administrative and legislative duties with her, grooming her for the top job.

In November 1996 the court added three Republican members, and in the 1997–1998 term, Keller wrote more opinions than anyone else. She told a reporter, “The court, as it existed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, took every opportunity to change established law to benefit defense attorneys. All we have done in the last few years is to fix those mistakes.”

Unfortunately, one of the things the CCA didn’t fix was the system of appointing appellate lawyers for indigent death row inmates. In 1995 the Legislature had passed a law granting such inmates “competent counsel” for their appeals; the CCA was in charge of finding the lawyers and paying them, but no standards or qualifications were established, and many inexperienced and unqualified lawyers ended up being appointed, some of whom filed negligible writs of habeas corpus—usually a prisoner’s last chance. A federal judge in 1997 granted a stay to a death row inmate who had been okayed for execution by the CCA even though his novice lawyer had filed a short, bizarre writ challenging the constitutionality of the 1995 law. The judge called the CCA’s appointment of the inexperienced lawyer “a cynical and reprehensible attempt to expedite [petitioner’s] execution at the expense of all semblance of fairness and integrity.”

In 1998 Keller wrote her most controversial decision. Back in 1986, a sixteen-year-old girl had been raped and murdered in New Caney. Four years later a man named Roy Criner was convicted of aggravated sexual assault and sentenced to 99 years. The only evidence was the testimony of three friends of his, who said that Criner had bragged about having rough sex with a girl who had been hitchhiking. In 1997, after several failed appeals, he took two DNA tests, both of which showed that it was not his semen in the girl. His attorneys moved for a new trial, which the trial judge recommended.

Keller said no. Her opinion reversed the trial court, arguing, “The new evidence does not establish innocence.” In other words, the process had been fair—Criner had been convicted by a jury and had already had his appeals. She granted an interview to the PBS show Frontline and embarrassed herself and the court, calling the victim “promiscuous” and saying Criner hadn’t established his innocence—even with DNA, which she treated as if it were a technicality. “Finality [of judgments] is important,” she said. After further DNA testing excluded Criner, Bush pardoned him.

In 2000 Keller ran for presiding judge. Her opponent, fellow judge Tom Price, asked, “How far to the right is this court going to be? Even Republicans want fair trials.” (Price would later say that the Criner case had made the court a “national laughingstock.”) Keller was asked in a preelection interview if she was bound to follow the law, even if it meant an unjust result. “Absolutely,” she replied. “Who is going to determine what justice is? Me? I think justice is achieved by following the law.” According to some who have worked with her, she was also answering to a higher power. “She’s extremely religious,” says a colleague. “She believes strongly that God is on her side.”

By the time Keller won the top job, the CCA had already begun to change, becoming more moderate, partly in reaction to the tumult of the previous years. After Cathy Cochran was appointed, in 2001, the court settled into a balanced existence, with three on the far right (Keller, Barbara Hervey, and Mike Keasler), three on the near left (Price, Johnson, and Larry Meyers), and three in the center (Cochran, Paul Womack, and Charles Holcomb). Cochran, a former defense lawyer, prosecutor, and law professor, in particular helped moderate the CCA. She is, defense attorney and legal analyst Brian Wice told me, “the intellectual heart and soul of the court.”

The court may have become more stable, but that didn’t mean the judges followed their leader. Keller, nicknamed “Mother Superior” by Meyers, was a tireless worker who would take on extra opinions when other judges fell behind. But she had never been, as she once acknowledged, a “leader-type person.” She often kept to herself, and she didn’t always take into account the wishes of her colleagues. “She causes resentment among other judges,” says a former court employee. “She’s not collaborative at all.”

In 2002 Keller unilaterally changed the group the CCA had chosen to train court-appointed lawyers from the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, which the other judges preferred, to an Austin organization called Dave’s Bar. The following year the court refused to renew the grant. That year the court also fired its longtime general counsel, Rick Wetzel, who had become a close ally of Keller’s, a decision that made her very unhappy and alienated her further.

About this time other judges began making conscious efforts to repair some of the problems in the state justice system. In 2004 Hervey began meeting with state lawmakers to help create more innocence projects (nonprofit groups, often based in law schools, that work to exonerate the wrongfully imprisoned). In 2006, under the leadership of Cochran and Johnson, the court established rules for helping to identify and remove incompetent court-appointed appellate attorneys. Two years later, at the behest of Hervey, the court created the Criminal Justice Integrity Unit to look into the causes of the astounding number of wrongful convictions in the state.

But as the court moderated, Keller, with a few exceptions, did not. In the 2006 election for presiding judge, Price noted how Keller had dissented more than any other judge. “Judge Keller has lost the confidence of the court,” he said, adding, “She keeps going to the right as far as she can.” Other judges might compromise principles to get votes, but not Keller—she stayed true to her conservative, pro-prosecutor ideals. Defense attorney Keith S. Hampton, who has argued many cases before the CCA, says, “I don’t see her as being nasty or mean-spirited to the defense. She walks through life with blinders on. I think there’s a blank in her experience.”

As usual, Keller was the first judge at the office on September 25, 2007, arriving at about 6. All the judges knew it was an execution day—Ed Marty, the general counsel (a kind of all-powerful legal office manager), had previously sent around a list of upcoming executions, with each one assigned to a duty judge. “The key to all death penalty cases is the duty judge,” Wetzel told me. “Internally the duty judge needs to get it together and garner the votes to determine the court’s decision.” That night the duty judge was Johnson, and she, Price, and Womack had planned to stay into the night in anticipation of late filings for Richard’s execution. They would be joined by other staff, including Marty, a twenty-year Army veteran and former Smith County assistant DA, who’d taken over for Wetzel after he was fired.

No one doubted Michael Richard’s guilt. In 1986 he had raped and killed Marguerite Dixon, a mother of seven, in Hockley, near Houston. Richard, whose IQ was 64, six points below the standard used in Texas to determine mental retardation, had been on death row since 1987. In fact, he had had his first conviction overturned by the CCA in 1992 because the jury hadn’t been told to consider his childhood (he had been beaten by his father with whips and belts) during the punishment phase. He had been convicted again, in 1995, but in 2002 the U.S. Supreme Court decided Atkins v. Virginia, which held that states could not execute the mentally disabled. Richard’s lawyers filed a writ of habeas corpus in state court based on this claim, and the CCA sent his case back to the trial court to see if he was indeed mentally disabled. The trial judge said he wasn’t—and so did the CCA. The execution was on again.

On September 17, 2007, Richard’s attorneys, who were part of the Texas Defender Service—a nonprofit group with offices in Houston and Austin that defends many of the prisoners on death row—filed a supplemental federal claim based on the Atkins decision, contending that Richard’s mental state had never been adequately presented. “There’s a line with these cases, and people are on one side or the other,” says David Dow, TDS’s litigation director and a University of Houston law professor. “Richard was clearly on the mentally retarded side of the line.”

At 9 a.m. on September 25, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it had agreed to hear Baze v. Rees, a Kentucky case that raised the issue of whether the chemicals used in lethal injections constituted cruel and unusual punishment. Though the court would not decide Baze for another six and a half months, its decision to consider the issue meant that death penalty appellate attorneys all over the country could challenge impending executions. The TDS lawyers had a new weapon, but to get the Supreme Court to weigh in on Richard’s case, they first had to exhaust their claims with the CCA, and they didn’t have much time. TDS lawyer Greg Wiercioch e-mailed Dow, who got the message after teaching a contracts class. At 11, Dow, Wiercioch, and six other TDS lawyers had a phone conference to figure out how to proceed. Dow and Alma Lagarda—a lawyer in the Houston office—would work the Baze claim while Wiercioch would keep working the Atkins claim.

At 11:29, Marty sent out an e-mail making sure that all the judges knew about the Supreme Court’s intention to hear Baze. At some point the judges polled themselves and found they were 5—4 against granting a stay. Marty began drafting an order denying the motion while Price began drafting a dissent. Sometime after lunch Keller left the office to meet her repairman.

Around two, Baxter Morgan, an assistant attorney general, called Wiercioch. The state attorney general’s office represents the prison system and on execution day ensures there are no outstanding defense claims pending. Wiercioch told Morgan that the TDS was working on a lethal injection claim. At 2:40, Marty sent around an e-mail, “Michael Wayne Richard update,” saying he had just talked with the Harris County DA’s office, who said the TDS lawyers were filing a lethal injection writ.

At 3:30 Lagarda finished her draft of the TDS filing, which included three things: a motion to file a writ of prohibition, a petition to file a successor writ of habeas corpus, and a motion for a stay of execution. Dow edited the draft, and when he was finished, at about 4, the appeal was 107 pages long. The plan was to e-mail it back to Lagarda, who would add the necessary attachments and send it to the Austin office, which would print it out, make eleven copies, and hand-deliver it to the CCA clerk’s office, about a mile away, just north of the state capitol. The CCA, unlike most high courts, did not accept e-mail filings.

But Dow wasn’t able to e-mail the document to Lagarda. “I thought it was a server problem,” he told me. By the time the problem was fixed, at about 4:30, Dow realized how little time they had left. So he decided not to file a writ of habeas corpus, just the other two motions. Still, they needed more time.

Dow told Lagarda to ask Austin-based paralegal Rindy Fox to call Abel Acosta, who has been the CCA’s chief deputy clerk since 1999. “Rindy has a relationship with Abel,” Dow told me. “She has routinely called him for five years now.” Fox was on the way home from a doctor’s appointment when she called Acosta, at about 4:40. According to the Commission on Judicial Conduct’s “factual allegations” (which, since they are allegations, will be a source of contention at the trial), she asked that the court accept a late filing. But Keller’s attorney, Chip Babcock, says that “according to Acosta, [Fox] did not state the name of the case (although he knew it related to an execution) and did not state what it was that the TDS wished to file.” Acosta told Fox that the clerk’s office closed at 5 but he’d see if the court would accept a late filing. He called Marty, who called Keller. (Acosta declined to be interviewed for this story.)

“I got a phone call shortly before five,” Keller told the Austin American-Statesman, “and was told that the defendant had asked us to stay open. I asked why, and no reason was given. And I know that that is not what other people have said, but that’s the truth. They did not tell us they had computer failure. And given the late request, and with no reason given, I just said, ‘We close at five.’ I didn’t really think of it as a decision as much as a statement.”

Marty hung up and called Acosta back at about 4:48. The answer was no, and Acosta called Fox and told her. She asked if she could leave the filing with a security guard, but Acosta said (again, according to the CJC’s factual allegations) that he “did not know what good that would do because no filing would be accepted after five p.m.” (Babcock says, “Acosta’s recollection of his conversation with Fox is substantially different from hers.”) At 4:59, Keller called Marty and asked if the TDS had filed anything. He said no. Meanwhile the file had been e-mailed to the Austin office, where it was being copied. At 5:10, Fox called Acosta again and said that the documents were almost ready—could they e-mail them? He said no.

The TDS lawyers were stunned by the court’s refusal, but they still had a few cards left to play. At 5:45 Morgan checked in with Wiercioch, who asked him to hold off on the execution, since Dow was filing a Baze claim with the Supreme Court. Morgan agreed to wait. Dow also sent Sally Sepulveda, his office administrator, to the Harris County district court to file the motions he had just finished for the CCA, an attempt to get into the state court as a predicate for getting to the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, the motions could be filed only with the CCA; even worse, the TDS hadn’t filed a writ of habeas corpus with the trial court—the one thing it could have filed there—which the court would have then sent to the CCA.

Just before 6, Fox called Acosta a final time and said they were on their way with the pleading. The CJC alleges that “Mr. Acosta told TDS not to bother, because no one was there to accept the filing.” Dow e-mailed the motion for a stay to the Supreme Court based on its Baze decision earlier in the day. He noted that “the clerk of the [CCA] refused to remain open past 5 p.m. to permit Mr. Richard’s counsel to file [the] pleadings.”

At 6, at the Walls Unit, 29 witnesses gathered in rooms near the execution chamber, waiting for the final word. Richard sat in a cell nearby. At 7:30 the Supreme Court turned down the lethal injection claim with no explanation, and soon after, Governor Rick Perry denied Richard’s request for a reprieve. Morgan called Wiercioch one last time. “Is this it?” he asked. Wiercioch said yes. All obstacles to Richard’s execution were gone, and he was taken from the waiting cell to the execution chamber and strapped down. An IV was placed in each of his arms. At 8:10 the witnesses were led into two rooms adjacent to the chamber. “I’d like my family to take care of each other,” Richard said. “Let’s ride. I guess this is it.” He closed his eyes. At 8:23 he was dead.

Would the Supreme Court have granted the stay if the CCA had acted on it? No one will ever know, but two days later, TDS lawyers for Carlton Turner, the next inmate scheduled for lethal injection, filed a motion for a stay on the same Baze issue with the CCA, which denied it by a vote of 5—4. Then they filed it with the U.S. Supreme Court, which granted it, halting his execution.

At the court’s weekly conference the next morning, some of the other judges—who didn’t know about the previous night’s drama—remarked how odd it was that, given the Baze decision, the TDS hadn’t filed a motion for a stay. Keller posed a hypothetical question to Cochran that involved a phone call to the clerk and a request to file late. Cochran said that of course the court should allow it. Keller gave her answer: “The clerk’s office closes at five; it’s not a policy, it’s a fact.” She didn’t tell anyone about the incident.

The other judges found out about it by reading a story in the Statesman on September 29. Four days later, the usually press-shy Johnson said how angry she had been when she found out about the evening’s events. “If I’m in charge of the execution, I ought to have known about those things, and I ought to have been asked whether I was willing to stay late and accept those filings.” She said that obviously she would have taken the brief. “Sure. I mean, this is a death case.”

A week later, a group of twenty lawyers announced they were filing an official complaint with the CJC. On October 19, 130 lawyers from Harris County filed another one. Four days after that the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers filed its first-ever complaint against a judge, calling Keller’s actions a “shocking breakdown.” The Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association followed suit. State newspapers were unanimous in their condemnations.

Keller was bewildered. “I talked to her shortly after the whole thing blew up,” recalls an old friend. “She said she had been dealing with the plumber, someone called and said, ‘We need to stay open,’ and she stated a fact, ‘The clerk closes at five.’ She told me, ‘I don’t know what this is about.’” This would explain why Keller hadn’t directly addressed the incident at the next day’s conference. It was, however, a big enough deal to the other judges that the court soon changed its practices, putting its execution day policies in writing and allowing e-mail filings.

The CJC hired Mike McKetta, from Graves Dougherty Hearon and Moody, in Austin, to prosecute Keller—for $1. Keller hired noted defense attorney Babcock. This past March, he submitted her response. She denied all allegations and claimed that the charges were unconstitutional because she “has been denied the right to counsel”—the CJC wouldn’t pay for Babcock’s services or allow her to be represented at a cut rate, since that could violate ethics rules, which prohibit judges from accepting gifts. Keller claimed she was risking “a financially ruinous legal bill.” Her problems got worse when the Morning News reported on March 30 that for seven years Keller had been violating Texas Ethics Commission requirements on her financial disclosure statements. In 2008 she had reported earnings of $275,000 from salary ($152,500), stock, and two homes; however, Keller hadn’t listed seven other properties, worth a total of $1.9 million, including two that were still listed under her married name, Sharon Batjer. She also didn’t list $3 million in property owned by three Keller family corporations and trusts.

The head of Texans for Public Justice filed a criminal complaint with the TEC. (If the TEC finds that there was a violation, Keller could be subject to a fine and even jail time.) Keller’s civil attorney, Ed Shack, said it was an inadvertent mistake and offered an explanation: Back in 2002, Keller had made copies of documents listing her property holdings, but two pages had fallen out of the stack and were never copied. On April 28 she filed an amended statement, disclosing seven more properties, 22 CDs in four banks, and her status as officer or director of three family businesses. Total value: an additional $2.4 million. Keller’s excuse: “My father, Jack Keller, over a number of years has acquired and managed, without input from me, all of these properties.”

Cactus Jack has played such a major role in his daughter’s life that this claim is certainly credible. On the other hand, could Keller—the circumspect, overachieving, rule-following judge—really have been this careless?

Soon the judge will have her own day in court, before special master Berchelmann. Her defense will rest on several things, first and most important her interpretation of the infamous phone call. She has said she thought Marty was asking specifically about the clerk’s office, which, like all state offices, closes at five and never stays open late. “It is clear that Judge Keller did not have a duty to do anything other than what she did,” her response to the CJC says, “which was to answer a question about whether the clerk’s office closes at 5:00 p.m.” In other words, Keller followed the rules—as she had always done. But Marty told the CJC that he said either “They want the court to stay open late” or “They want to hold the court open.” If Berchelmann determines that he said (and that Keller understood him to say) “court,” the special master might rule that Keller had a duty to do more than she did. That’s because for years the CCA has had an unwritten policy of keeping the court open on execution days, even after the clerk’s office closes (which would explain why Johnson, Price, and Womack stayed late that night). This informal practice was carried out through the general counsel’s office. Wetzel, who held the post from 1987 to 2003, says, “Typically lawyers would contact judges through me, and I’d get in touch with the other judges and get a vote on what was filed. Defense lawyers had my phone number—they could call me at home. I had pleadings delivered to my home, or they’d fax things after-hours. My experience with defense lawyers—they know that five p.m. doesn’t mean the court is closed.”

In defense of Keller, Babcock will blame Richard’s attorneys for not doing all they could to halt his execution. According to section 9.2(a)(2) of the Rules of Appellate Procedure, the attorneys could have called any judge on the court and delivered a filing to him or her, before or after five. While this tool has been around for years, very few defense lawyers have ever actually called a judge, even on execution days. In legal lingo this is known as an ex parte communication, one side contacting the judge without the other side present, and, says Wetzel, it is a delicate matter: “There’s a fine line between delivering papers to a judge and discussing the merits of a case.” I asked Cochran if she had ever been phoned by a defense lawyer seeking to file a pleading. “Never,” she said. “I would consider it an ex parte communication. I don’t want to be put in that position. If the clerk’s office is closed, the general counsel is the normal person you go to.”

At any point during the day, and especially as time was running out, the attorneys could also have faxed or even hand-delivered a short, handwritten writ or motion to the CCA. Brian Wice says, “There was nothing to prevent TDS from calling the clerk’s office and saying, ‘I’m on my way with a writ,’ then pulling out a Big Chief pad.” The attorneys also could have filed a short, hand-scribbled writ of habeas corpus in the Harris County trial court. Instead they filed the two motions they’d tried to file with the CCA, two kinds of motions the trial court could not act on. Judge Meyers says, “If TDS had gone to the trial judge and dropped a writ of habeas corpus, that would have acted as a virtual stay. That’s how we’ve done it in the past. They could have done it from noon up until six p.m.”

The crew of passionate, hardworking lawyers at the TDS doesn’t come off well in the whole affair, from the dog-ate-my-homework excuse of having computer problems to their decision to use a paralegal instead of an attorney to handle the crucial communications with the court. Wiercioch told Texas Lawyer that the intense back-and-forth “took the air out of me, every last bit of energy. I wasn’t sure what to do. I still held out the hope that we were going to be allowed to file this thing.”

Keller will likely also blame Marty, the general counsel, who retired in August 2008 in large part because of the controversy. Why did he even call Keller at home? Why not go straight to the duty judge? (Attempts to reach Marty were unsuccessful.) I asked Wetzel if his successor had a responsibility to tell the TDS about duty judge Johnson. “Clearly, if it was apparent someone was trying to file pleadings and they were floundering and didn’t know what they were doing and an execution was imminent, somebody should have told them how to get those pleadings before the court. ‘If you can’t get here by five, here’s my e-mail. Meet me on the loading dock.’”

The biggest question, the one at the heart of the whole case: Even considering the TDS’s fumbling and Marty’s questionable decision-making, did Keller, no matter whether she thought the question regarded the office or the court itself, have a duty to tell Marty to inform Johnson that the TDS was trying to file something? Did she have an obligation to do more than she did? Keller clearly thinks not, and Meyers agrees: “Judge Keller had no more duty than anyone else.” So does John Jasuta, the CCA’s former chief staff attorney: “The court’s staff could have been more proactive in terms of communicating, as they have been in the past, but there is no requirement that they seek out business. That is the job of the litigant seeking relief.”

But not everyone sees it that way. Judge Michol O’Connor, who wrote a textbook on Texas civil procedure, says, “Her response to Marty should have been, ‘Why are you calling me? Call the duty judge.’” Johnson told the Statesman she would have accepted a late filing—and she put her money where her mouth is in January of this year, when the TDS attorneys for death row inmate Larry Swearingen, who was set to be executed on Tuesday, January 27, showed up at the court on the preceding Friday at 5:01 (they called first to say they were having copying problems) and were told by new general counsel Sian Schilhab and Acosta that the pleadings would not be entered into the court record until Monday morning. Swearingen’s attorneys, who had learned the lessons of Richard, called Johnson, who told Acosta to return to the courthouse and accept the filing. (The CCA denied the stay, but the Fifth Circuit granted it.)

“I don’t know what I would have done,” says Meyers. “We’re not supposed to counsel these people on what to do. We’re under the presumption that they are highly specialized attorneys. From a technical standpoint I don’t think she did anything wrong. She didn’t do anything not prescribed by the code.”

I asked Cochran about the distinction Keller’s defense makes between “clerk’s office” and “court.” “The bottom line is, we accept anything and everything before an execution takes place,” she says. “We will do whatever it takes.” Did she have any doubt about whether she would have made it happen? “No. I can’t imagine the concept of not accepting a death penalty filing even though it’s after the clerk’s office closes. That’s what courts are for. The Supreme Court doesn’t close on death days. It would have been so easy to say, ‘Mr. Marty, tell ’em to fax it.’

“Sometimes you just do the right thing. The right thing is not to close the courthouse when someone is about to be executed.”

After the trial, Berchelmann will file a report with the CJC, which will have three options: Dismiss the charges, give Keller a reprimand, or recommend that she be removed from office. If it votes to remove, she can appeal to a review tribunal of seven members appointed by the state Supreme Court. If Keller loses again (only four cases have ever been appealed, and in each one the removal was upheld), she can go to the state Supreme Court. In other words, the process could grind on for a while.

And she has given every indication that she won’t back down anytime soon. “I wouldn’t anticipate her shying away from this fight,” says Wetzel. “She’s a very strong person. She has a sense of duty and obligation and believes the voters of the state of Texas selected her to her position, and she won’t shy away from it. She does what she believes she is supposed to do.”

Keller has picked up some unlikely allies, peers from within the legal community, such as former CCA judge Maloney, who, by his own estimate, has had half the decisions he’s written overturned by Keller and who believes that the TDS lawyers could have found other avenues into the CCA. “She can’t close that court,” he says. “She doesn’t have the authority. A lot of this is political posturing magnified by the press.” Anne Dingus, a die-hard liberal (and former Texas Monthly writer) who went to Rice with Keller and disagrees with her views on just about everything, says, “There’s a hostile element out to get her, like there is with Hillary Clinton—a capable, competent woman who happens to be on the other side of the political spectrum.” Jasuta agrees: “There’s something basically unfair about the way people are treating her. She’s not given the credit she’s due, even though she’s very competent and has brought positive changes to the court. For example, the CCA used to have a tremendous backlog, but it has been eliminated during her tenure.”

Keller has done other admirable things too. She chairs the boards of several committees, including the national Justice Center and the state Mental Health Task Force. She has probably accomplished the most on the Task Force on Indigent Defense, which was formed in 2002 as a direct result of the sleeping-lawyer fiascoes and other disastrous death penalty cases. Its goal is to guarantee trial counsel for poor defendants, mostly by setting up county public defender programs. Under Keller’s leadership, the number of public defender offices in the state has gone from seven to fifteen; more than one hundred counties are now covered. This year the task force’s budget is $30 million. “There’s no way the state would be where it’s at without her leadership,” says director Bethke. “If she didn’t care about this issue, the task force could have been nullified a long time ago.”

At the June 10 meeting of the task force, Bob Spangenberg, one of the nation’s leading experts on indigent defense programs, gave a presentation. “From 2002 through 2008,” he said, “Texas provided greater amounts of funds for indigent defendants than any state in the country. You’ve really done a wonderful job. Texas is no longer the death capital of the world—sleeping lawyers and all that stuff. People are tired of that—Texans are tired of that. And there’s a long ways to go.” Keller, in her canary-yellow suit, sat quietly, slightly swaying from side to side in her chair, a half-smile on her face. If she felt any pride at Spangenberg’s kudos, she didn’t show it. She also showed no discomfort at his veiled criticisms, but she really had no reason to. Keller was elected by Texans who are in fact not at all tired of the death penalty, who believe that if you kill someone, you deserve the ultimate punishment. Keller, the kind, decent, implacable face of the state criminal justice system, is proud to give it, with no compromise, no doubt, and no mercy.