This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The knocks came after midnight. We were in bed upstairs, sleeping so soundly that the noise seemed, at first, just part of a dream.

“That’s the door?” I asked, turning to see my husband already heading downstairs. I followed. Standing on the stoop outside was Richard Lyon, our duplex landlord, holding a baby monitor. His face was pale; his eyes were deep and tired. He spoke in a low, hoarse voice: Nancy, his wife, had been vomiting for hours. He was taking her to the emergency room. Could we please look after his daughters while he was gone?

We took the monitor without a thought. In the nearly six years we had lived side by side—sharing, as we did, a wall, a front porch, a back yard, and the cramped conditions of middle-income Park Cities housing—we had come to rely on each other for life’s little emergencies: electronic baby-sitting, pet care during vacations, newspapers retrieved from the rain. During the past year, especially, as their marriage crumbled and Richard was frequently gone, we had often come to Nancy’s aid. We helped when she was sick, collected her mail, listened for her phone. Now this.

“Don’t worry about the kids,” I said, as Richard headed back to his door. “And tell Nancy I hope she feels better.”

Six days later, she was dead.

Within two months, the official word was that Nancy Dillard Lyon had been poisoned. The Dallas County medical examiner, who ruled her death a homicide, found lethal concentrations of arsenic in her body. Richard, then 34, was arrested and charged with her murder. Less than a year later, he was convicted and given a life sentence.

From the start, the Lyon murder attracted national publicity and local curiosity. The victim was the daughter of a prominent Highland Park family and a partner in one of Trammell Crow’s residential companies. From her death on January 14, 1991, to Richard’s trial in December, there was a constant flow of new twists: suggestions of other suspects, rumors of incest, revelations about chemical purchases, and Nancy’s own suspicions that she was being poisoned.

Throughout those eleven months, I did all I could to believe that Richard had not poisoned his wife. At every opportunity, I turned distrust and fear into doubt and denial. I refused to follow the tide of opinion about my neighbor, refused to convict him without proof of his guilt. I knew Richard, I thought. We had lived so close—close enough to hear, as I did the night he took Nancy to the hospital, his last tender words to her in their bedroom. “I’m warming up the car,” his voice crackled through the monitor, inches from my ear. “Do you think you can make it downstairs? I’ll carry you.”

But what did I know? What does anyone know about anyone, even those who share your walls for years? You see their lives, hear them, only in fragments—steps on a stair, casual glimpses through a window, doors closing and opening, the sound of running water, a child’s cry or laugh. The pieces of their lives enter your consciousness, become as much a part of you as your own life. But in the end, you can only imagine what’s in their souls, even if it is unimaginable.

When I decided to write about Nancy’s death, many who knew her wouldn’t talk to me. They worried that I would take Richard’s side, or that I would expose too much, having lived so close. Am I violating some neighborly code of privacy? I only know I wouldn’t be writing this if Nancy had not died as she did. If anything, I would have written some nice little testament to the loss of a good neighbor. Maybe it would have inspired some nice little neighborly acts.

But this is not a nice little story. It is a story of lies and betrayal, ugly accusations and cold, calculated murder. And there is no inspiration in any of it.

It’s hard to say when my suspicions began. My sense is that I felt inklings of a sinister aura over Nancy’s illness from the start, but they were deep, intuitive, ill-defined. I couldn’t pin them down.

Maybe it was nothing more than the shock of it all. A 37-year-old woman, in seemingly good health, was suddenly lying in an intensive care unit with a team of doctors unable to stop her swift decline. At 1:50 a.m., when Nancy first entered Presbyterian Hospital’s emergency room, the doctors tried several medications to stop her vomiting. By 8 a.m., she was no better. She had been retching uncontrollably; her pulse was racing at 144; her blood pressure had dropped to 50 over 18.

When she was transferred to the ICU, doctors first suspected toxic shock syndrome. For more than a week, Nancy had complained of vaginal itching; two days earlier, she had begun taking Zovirax capsules for pimplelike lesions on her cervix. But she lacked the rash and high fever of toxic shock. Food poisoning looked doubtful too. Although she said she had eaten old pasta the night before, her symptoms had lasted too long. Puzzled, her doctors began to test for infections.

Within hours, family and friends gathered. Eventually, they would fill the waiting room and spill out into the hall. Most had known Nancy’s parents, Bill and Sue Dillard, for years. They had watched them bury one of their four children, thirty-year-old Tom, who died of a brain tumor in 1985. But nobody expected that Nancy would not make it. As she thrashed in pain, her family members urged her to fight. To boost her spirits, friends played tape recordings of her daughters, four-year-old Allison and two-year-old Anna, singing and talking to their mother.

Only when she continued to deteriorate did tensions escalate. On January 10 a friend of the Dillards’ showed up on our doorstep and suggested that we visit Richard in the waiting room. “There’s a lot of anger,” she said. “It’s the Dillards on one side, Richard on the other. What he really needs is friends.”

I went to the hospital that afternoon. The anger toward Richard didn’t surprise me. I knew the Dillards thought he had put Nancy through hell for the past year.

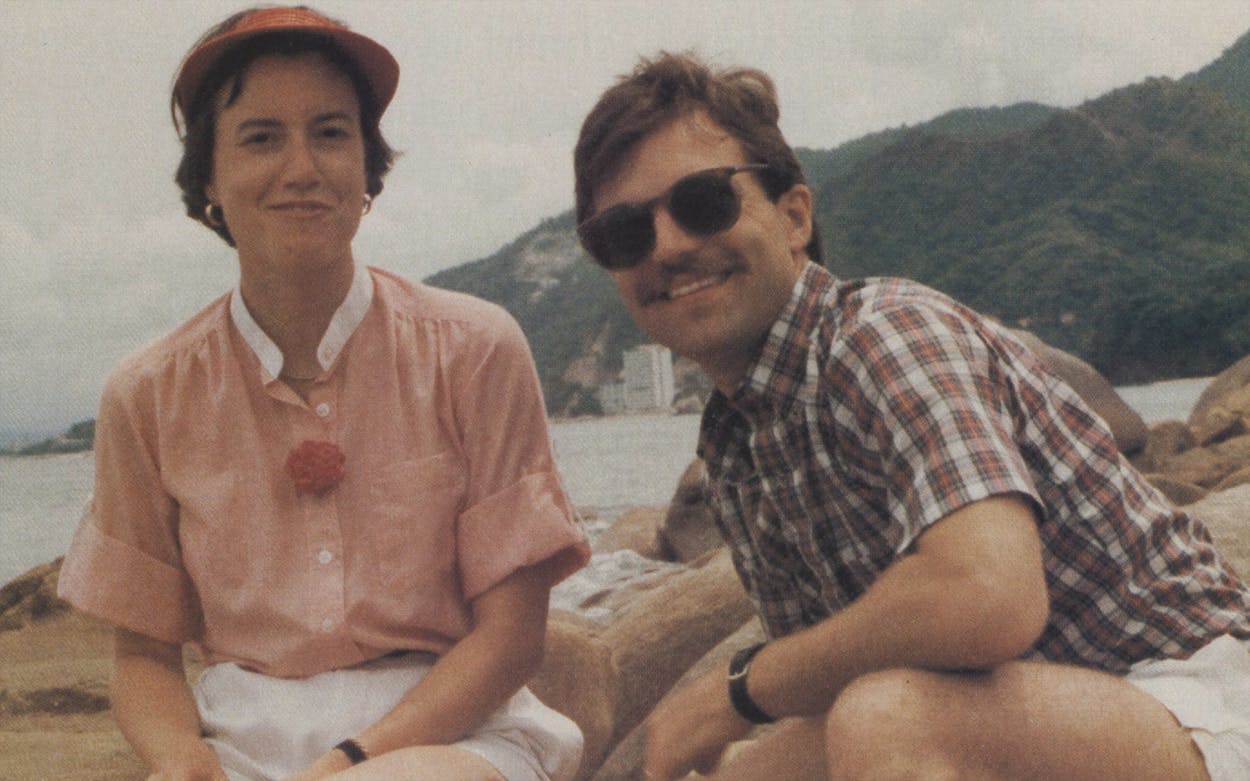

Nearly everyone was surprised, especially Nancy, when Richard grew so unhappy with the marriage. When we first became their tenants in 1985, they seemed a compatible, warm, active couple, with a homey friendliness and virtually no flash or friction in their lives. We never once heard them fight. Nancy was bright, ambitious, and full of cheerful energy, a small woman with short dark hair and a pretty face marked by jet-black eyes, alabaster skin, and large white teeth. Richard, a short man with wavy brown hair and chiseled features, was congenial, calm, conservative, and relentless in his puttering around the yard.

They had met six years earlier at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, where they studied landscaping and development together, and had come to Dallas at the crest of its land boom. They were intent on working hard, but they also freely took help from Nancy’s real estate developer father—Big Daddy, as his children called him—in the form of loans and business clout. In 1982, Nancy accepted a management job with longtime family friend Trammell Crow’s residential company. She rose quickly and made partner in a year. In 1984, in part from Bill Dillard’s recommendation, Richard was hired by developer Kenneth Hughes to oversee construction of his firm’s largest projects.

The couple busied themselves nearly all the time: sprucing up their property, directing family Christmas pageants, making Allison’s dollhouse shingle by shingle. At Harvard, they had teamed up on all their projects, working through the night until collapsing together in the single bed they shared. According to friends, Nancy had the ideas, Richard the speedy execution.

The constant activity bridged the striking differences in their backgrounds. Nancy had grown up among the manicured lawns and large brick homes of Highland Park, a rarefied world of close-knit, affluent, churchgoing families whose children sang Christmas carols together and spent summers at the country club pool. Richard had none of that breeding. He grew up in a middle-class neighborhood in small-town Connecticut, where his father sold insurance and his mother was a teacher’s aide. When he met Nancy in 1979, he didn’t even own a suit. At their wedding three years later, his relatives were daunted by the Dillards’ money and what they perceived to be their in-laws’ clannish ways. It bothered them that Richard didn’t quite fit in. His parents bristled when Nancy’s older brother, Bill Junior, jokingly toasted Richard at the rehearsal dinner as “a Yankee and a yardman.”

If Richard resented his wife’s family or her success, however, he never let on in those early years. The couple ate burgers at regular Dillard picnics by the Dallas Country Club pool and went on Dillard family vacations each summer. Richard worked with Nancy on her Junior League philanthropy projects. Particularly after Allison’s birth in 1986, the couple’s life meshed easily with Highland Park expectations: They hired a full-time nanny; they got their children on waiting lists for the best preschools; they taught in the Sunday school nursery. Yet they were never blatant materialists. Their life in the 1,100-square-foot duplex appeared simple and earnest. They spent weekend nights at home, renting old movies. On their own they transformed the once-scrawny back yard into a little paradise, planting trees and wisteria, driving bricks into sand to make a patio, hanging chimes and a hammock.

But my husband and I could see the stresses build. By 1988 the real estate boom had gone bust. Richard’s work with Hughes was slowing. In January 1989 their second daughter, Anna, was born with a hip problem. Their cramped space seemed nearly intolerable. All through that summer, we would listen to Anna’s crying in their bedroom. Richard was gone on business often.

In the fall of that year, we had heard only hints that the marriage was troubled, that Richard had met another woman and wanted out. The first real sign of their break came sadly and quietly the day after Christmas. We awoke to see their tree already stripped of its ornaments and lying on the front sidewalk to be hauled away. Richard was crouched in the driveway with a packed duffel bag on the ground beside him, his face bitter and unhappy as he held an arm around little Allison and spoke softly in her ear. Then he threw his bag into his red 1966 Mustang and drove off.

The separation left Nancy dumbfounded and distraught. He had told her he was going to a family counseling program in Arizona, but he ended up joining his girlfriend on a ski trip. Two weeks later he was back—only to move out again within a month. Yet through the next year, Nancy was endlessly willing to endure Richard’s occasional, always short-lived attempts at reconciliation, much to the increasing chagrin of her family and friends. “I know the real Richard,” she used to say. “This isn’t like him. He’s a family man. He’s sick, but I know he’ll come around.”

By early summer 1990, the separation was taking a physical toll on Nancy. She grew alarmingly thin. One morning she knocked on our door, handed us Anna, sat down on our front step, and vomited. We got a bucket and called her parents. Later that day I took her some soup. Her doctor attributed the illness to antibiotics, she said. Two weeks later she told me that she tried taking the same pills again and again got sick.

The incident became, for me, a metaphor for the sense of rot I began to feel at the duplex that summer. Maybe it was just the image of their garden—which, once lavish, was now withered and infested. I began watering and tending it. Each night, I straightened up the yard and washed off the porch.

When Richard filed for divorce in September, I was actually relieved. The finality seemed to strengthen Nancy. Her attorney requested that she get sole custody of the children, child support, and rights to as much as $260,000 in separate assets. One settlement proposal suggested that Richard was willing to give Nancy most of what she wanted. For the first time, I heard her speak hopefully about herself. She mentioned moving to Washington, D.C., to work.

Then, by mid-November, Richard began appearing at the duplex. We were surprised and skeptical at first. When I asked Nancy about it, she told me that Richard wanted to reconcile and that she had asked him to prove it. Suddenly the place came alive. The couple began planning a new back yard, including a playhouse that Richard was building himself, working late into the freezing nights to finish it before Christmas. He put a wood-burning fireplace in the living room and, at Nancy’s request, painted the downstairs walls a funky red. In the evenings he built pillow forts with the kids and played his guitar. The atmosphere was so lively that my 21-month-old son, Shawn, began yearning to visit. One morning, without my knowing it, he wandered out of our door. I found him eating apple slices at their breakfast table.

So that was my view on January 10, 1991, when I decided to visit Richard in the hospital waiting room. I had a certain amount of compassion for him. If there was anger, I thought, it was because the Dillards didn’t understand how much he had been around, how so much had seemed to change.

I entered carrying a bag of deli sandwiches. The waiting room was crowded. Richard was sitting in one corner with a group, looking pale but refreshed from a shower. I went directly to him, gave him the sandwiches, and hugged him.

“I’m so sorry,” I said.

“About what?” he asked.

I flushed and paused for a moment, unsure of what to say. “Well,” I said, “I’m sorry Nancy’s so sick.”

Six hours after I left, Nancy’s lungs failed. She was sedated and placed on a respirator. She never communicated again. By the time she was taken off life support on January 14, she was a bloated, unrecognizable figure. The intravenous attempts to bring up her blood pressure had pumped nearly forty pounds of excess fluids into her body.

At the time of Nancy’s death, the doctors still didn’t know the exact cause. But hours after she was admitted on January 9, her father told Dr. Ali Bagheri, the resident overseeing her care, that the family suspected Richard had poisoned Nancy. A few days later, her brother Bill told the Dallas County district attorney the same thing.

Nancy, it turned out, had suspected Richard of poisoning her four months earlier. She had related her fears to her divorce lawyer, Mary Henrich, and to her sister-in-law, Mary Helen Dillard. In early September, she told them, she found a bottle of wine on her porch with an anonymous note to her; the cork looked as if it had been tampered with. Soon after, Nancy said, she and Richard went to the movies. When Richard brought her a soft drink, she took one sip and immediately spit it out because of a foul taste. She then saw a white powder floating on top. According to Henrich, Nancy said Richard “threw a fit” because she didn’t drink it. She said she was sick that night.

It’s hard to say why Nancy would have reconciled with Richard in the face of such suspicions, which apparently continued. Henrich urged her to have the wine tested, but Nancy never followed through, saying it would embarrass her to accuse her husband. Then, in late October, friends saw Nancy with a collection of unusual “health pills” Richard had given her. In December, after she and Richard went on a ski weekend in Colorado, Nancy told Mary Helen she had stayed in the bathroom vomiting for an entire night during the trip. Richard, she said, never once got out of bed to check on her.

After Nancy’s father talked to Bagheri, it was at least ten hours before the doctor did anything. Bagheri later testified that his patient load was busy that day and that he was waiting for Richard to leave Nancy’s bedside so he could talk to her alone. Finally, around midnight, he saw Nancy in her room. She told him about the soft drink, about the wine and the health pills. When Bagheri left Nancy that night, he recalled, she was writhing in pain, pleading with him to find out what was wrong with her. “I remember what she said,” he testified. “ ‘Please help me. Help me. Don’t let me die.’ ”

Early the next morning, Bagheri asked the Dillards to search the duplex. Later that day, they returned with a red bag. Inside was an eight-compartment container filled with various pills and an open bottle of wine. The bags had been in the car trunk of Allison and Anna’s nanny, who said she saw Nancy place them there amid sundry garage sale items a few months earlier. Richard, meanwhile, apparently knew nothing of the Dillard family’s suspicions. Shortly after Nancy was admitted to the ICU, he himself asked doctors if tainted food could have made her ill. He said she had been drinking foul-tasting coffee the morning before she got sick. He brought in a bag of food from the house to be tested.

By this point, I later learned, observers were clearly divided into two camps. Doctors viewed Richard’s efforts with skepticism, and Nancy’s family and friends were quick to catalog his misplaced gestures, indifferent responses, and odd refusal to leave her bedside. Yet others saw nothing strange about Richard’s behavior. They saw him pray with his minister. They saw him barely sleep. When Nancy died, he appeared as bereft as any husband would be.

Gary Perkins, a business associate and close friend of Richard’s, came to the hospital just as Nancy’s life support was being turned off. At first Perkins was directed to an upstairs waiting room where the Dillards were congregating separately from Richard. When he walked off the elevator and asked for Richard, he felt a discernible chill. A woman showed him downstairs to a room where Richard’s parents sat alone, waiting for their son to exit Nancy’s room. “Richard came out, and he was crying real hard,” Perkins recalls. “He was surprised to see me, and he hugged me. It upset me, because I’d never seen him upset like that.”

Perkins ended up driving Richard home. It wasn’t until they were in the car that he learned Nancy had died. “I cried and told him I was sorry,” Perkins says. “He had her pair of shoes there in his lap and he kept rubbing them in his hands. Man, it just ripped me apart. I couldn’t stand it. And he kept saying, ‘How am I going to tell my girls? How am I going to tell them?’ ”

The day before Nancy died, I took down their Christmas lights. I raked and swept the back yard, picking up pieces of wood shavings, screws, and nails while my son played.

In the center of the small lawn stood a stone statue of a curly haired angel playing a harp. Richard had given it to Nancy for Christmas. For some reason, my son knew it was hers and would occasionally point to it and call out her name. When he did, I felt a loss of surprising depth. I hadn’t known Nancy as a close friend; although we had talked nearly every day, our relationship was seasoned with a cordial neighborly distance.

For a long time, in fact, Nancy was nothing more to me than a good neighbor. She practiced that art well. When we first moved in, she would bring us gifts of soup or ice cream. If she borrowed a dish, she would always return it filled with something she or Richard had cooked. She remembered us every Christmas with a gift of raspberry vinegar or a basket of fruit. My husband—who is rarely hyperbolic about anyone—began calling her “the nicest person in the world.”

Admittedly, Nancy could be aggravating. Often we would step over dirty dishes or half-full coffee mugs that she would leave for hours on the front stoop. When her children painted on the upstairs porch, globs of red or blue would drip onto the stroller we kept near our door. And in conversation, she could be infuriatingly optimistic, addressing problems with empty platitudes about how everything would work out. Even after Richard left, even as her world fell apart, she tried to hang on to her rosy views. Yet when she couldn’t, she seemed more approachable, softer, more real. She had quit her job shortly after Richard moved out, intent on giving her daughters stability through the marital chaos. I was home with a child too. Together we began to forge a silent household alliance. On warm days and evenings our doors would swing open and our children would run back and forth, playing together as Nancy and I stayed on separate sides working or cooking. We would take turns keeping an eye on the kids. On some days we would borrow sugar, noodles, or milk from each other with an almost comic style.

As the months passed, our reliance on each other grew. At times she would say how grateful she felt with us living so close, how comforting our mere presence was to her, how safe she felt. For me, too, Nancy’s movements became etched into my daily routine. The sound of her step at night. The slamming of her door. The smell of her cooking. The sight of the toys strewn on her living room floor. The music she played.

Then, suddenly, she was gone.

Immediately after Nancy’s death the police advised the Dillards to keep up appearances with Richard. In retrospect, it amazes me how convincingly they played their roles. They received scores of guests at their home. During the funeral, which drew hundreds, Richard sat in the front pew next to Nancy’s mother. The two wept with their arms around each other as they sang “Amazing Grace.” At the grave site, her family calmly watched Richard hold Allison close.

In the weeks that followed, Nancy’s father came by the duplex nearly every other morning with a box of fresh-baked muffins. He sometimes helped with the household tasks or the children until Richard drove them to school. My husband and I tried to help Richard too. We baby-sat when he went to a grief-recovery program. We cooked him dinners. We tried to offer him chances to talk, although we knew he didn’t bare his feelings easily. But it seemed to us that Richard was finding a way to cope with his wife’s death. With his old energy and industriousness, he took up the backyard work he and Nancy had begun. He built a greenhouse. He bought rabbits for his daughters and made an open bunny hutch. He moved the angel statue into the center of the vegetable garden and planned to put a little washtub fountain in front of it—a makeshift memorial to his dead wife.

As I write this now, it seems almost absurd that I held so firmly to the idea that Richard was above suspicion. I am not—as few in Dallas are, I suppose—naive about spousal murders. I know that seemingly fine, upstanding men in our community are capable of strangling, smothering, or otherwise mutilating their wives to death. But I could see no such capacity for evil in Richard; nor could friends or co-workers. “Nothing ever suggested Richard could do this kind of thing,” said one of Richard’s former employers. “Richard would get mad, sure, but it was never, never carried out in the form of retribution.”

As a child, Richard was, according to his parents, always quiet and independent, rarely outwardly emotional but always amiable. He was drawn to art and music, did well in school, and showed signs of being a perfectionist. By age 28, he was competently directing multimillion-dollar construction projects and, all the while, earning the affection of colleagues, who saw him as generous and honest. He once gave his secretary $500 to help with a down payment on her house; he paid his associate Gary Perkins $5,000 from his personal account when a company check was late. Perkins, who worked nearly every day with Richard through 1989, describes him as a gentle man who never lost his temper on the job. “Richard would get angry, and he would voice his anger,” Perkins says, “but he always maintained control.”

By all accounts Richard also impressed the Dillards with his creativity and work ethic. As Nancy’s father wrote in 1989, recommending him for membership in the Dallas Salesmanship Club, “I have had ten years to observe his personality, drive, wit, and determination. Richard is hard-working, serious, and dedicated, but he can laugh at himself and has a great appreciation for the simple pleasures in life.”

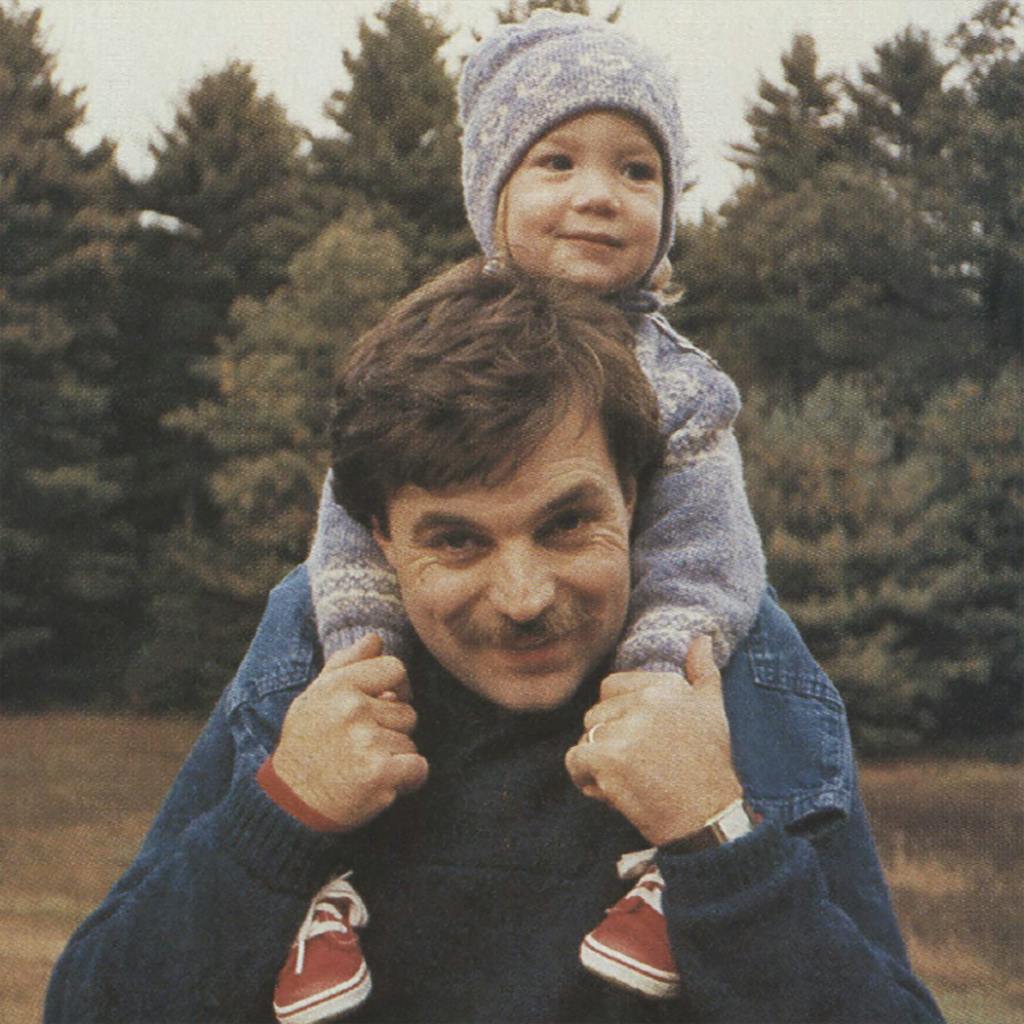

“He was the Pied Piper of all times with kids,” says an acquaintance. “He’d get out on the lawn at these picnics, and all the parents would be eating and drinking, and Richard was just there frolicking with the kids and having a good time.”

When Richard left Nancy, however, her friends saw him change; he became disdainful, cold, and angry. Yet Nancy would always defend him, saying he was simply having an acute mid-life crisis. “Richard had always been so compliant in his family,” says Emily Comstock, a longtime friend of Nancy’s. “I think Nancy felt like he just hit a point where he didn’t want to be a good boy anymore.”

I first saw Tami Ayn Gaisford at the duplex just a few days after Nancy’s funeral. Her car was parked in the driveway, with the same “94.5—The Edge” bumper sticker that had appeared on Richard’s Mustang shortly after he had left Nancy. As I walked to our door, I glanced briefly through Richard’s window and saw a blond sitting at the dinner table with Richard and the girls.

She appeared every two or three days after that, once lazily reading while he worked in the back yard. At first I didn’t recognize her as the “other woman” that Nancy had mentioned. She was not, as Nancy had said, a sultry, miniskirted hussy who frequented bars. She was fit and attractive, with a demeanor undoubtedly sensual but not at all cheap. The daughter of a residential contractor in Dallas, Ayn Gaisford was an intelligent, reasonable woman who had met Richard in the summer of 1989 while both worked on the renovation of the Saks Fifth Avenue Pavilion in Houston.

As I later learned, the affair had not been a casual one. For Christmas 1989, Richard had bought her a $4,900 ring. And their affection appeared mutual and deep, lasting even through Richard’s attempts at reconciliation with Nancy. “Richard knew he was in love with Ayn,” says one business associate who knew them. “What to do about it was the confusing part. He loved his kids.”

Obviously it was awkward seeing Ayn at the duplex so soon after Nancy’s death. It was unseemly, really—particularly late one night in early February, when I heard laughter in the back yard and saw her, Richard, and another couple having a dinner party. One early February morning I opened our dining room blinds at the exact moment she walked out of Richard’s back door, carrying a small overnight bag.

Yet I continued to give Richard the benefit of the doubt. He had few close friends, I thought; who was I to decide what he needed in his grief?

There was, after all, so much I didn’t know.

On January 15, one day after Nancy’s death, an autopsy was conducted by the Dallas County medical examiner’s office. It would show lethal doses of arsenic in her liver and kidneys. Her blood had as much as one hundred times more arsenic than normal. Her hair showed as much as forty times the normal amount at the root. That day, Detective Don S. Ortega of the Dallas Police Department’s homicide unit met with Nancy’s father. Ortega told him the investigation would take a while. In most cases Ortega questions his prime suspect within a day or two, but this one was trickier. This time he would wait.

The Dillards had told him that during 1990 Nancy had seen a canceled check from Richard to General Laboratory Supply, a chemical distributor in Pasadena. Apparently worried that Richard was using drugs, Nancy had mentioned the laboratory’s name to her sister. Ortega subpoenaed bank records for Richard’s accounts and asked General Labs to search their files. Within a month he obtained receipts showing Richard had bought several toxic chemicals in powdered form, including barium carbonate and sodium nitroferricyanide, from the supplier throughout 1990. None showed an arsenic purchase.

In late February the duplex grew quiet for days. Richard had told the Dillards he was going fishing in Mexico with a friend named John, and he left his daughters with Bill Junior’s family. While he was gone, Ortega checked airline records and discovered Richard had flown to Puerta Vallarta with Ayn Gaisford. Their return date was February 25. Ortega picked up Richard for questioning two days later.

Richard, pleasant and cooperative, spent five hours downtown with Ortega. During their talk, Ortega recalls, Richard’s eye contact never wavered. He answered questions calmly, without obvious emotion—even at times when Ortega felt emotion was warranted.

Ortega already knew that in the 44 days since Nancy’s death, Richard hadn’t once called the medical examiner’s office to ask about the autopsy results. When he told Richard that Nancy had been poisoned, Richard barely reacted. “He remained calm,” Ortega testified. “He didn’t say anything and did not appear upset. No response at all.” The most telling moment, in Ortega’s view, came when he asked Richard if he had any poisons at the duplex. Richard mentioned that Amdro, an ant killer, and Vapam, a herbicide, were stored in the garage. When he then asked if Richard had ever bought any chemicals, Ortega testified, Richard “thought for a moment and then said, ‘No.’ ”

“Right then, I knew I’d found my suspect,” Ortega told me after the trial. “I knew that he killed her. He lied to me, and I let him lie to me.”

In Ortega’s view, Richard’s lies only continued. When he asked if Richard had ever bought chemicals “from a laboratory outside Houston,” Richard said he had: mercury and lead to repair a battery, along with cyanide and “arsenic acid” to kill fire ants. At first Richard said he didn’t recall what he had done with the poisons; later he said he had put them in a trash bag and thrown them away. After the interview, Richard allowed police officers to search the duplex and his car. They turned up no evidence—no tainted food, none of the chemicals purchased by Richard, and no medication in Nancy’s name, not even the Zovirax capsules prescribed by her gynecologist just two days before she got sick.

As it happened, Richard had ordered arsenic, in both liquid and powder form, on November 19, 1990, from General Labs. On December 26, Richard called the company to ask about its status and was told it should arrive within two weeks. The package was delivered to Richard’s office the next day. Early that morning, Richard, Nancy, and the children had left Dallas on a flight to Connecticut. A receptionist signed for the package and placed it in the mail room. The earliest Richard could have picked it up was January 3, six days before Nancy went to the hospital.

At the trial, when Richard took the stand in his defense, he told a different version of his talk with Ortega. He said he initially answered no to the question about chemicals because he thought Ortega was asking about pesticides. And he testified that he never told Ortega that he had received the December 27 delivery of arsenic.

In fact, nobody was ever able to prove Richard had actually picked up the arsenic at his office. Shortly after Richard’s arrest in May, he contacted the receptionist who signed for the delivery and asked her if she remembered him complaining that he hadn’t received a package. The receptionist said she didn’t recall any such complaint—yet neither she nor any other witnesses saw Richard take the package from the mail room.

It was nearly three months after Richard’s trip downtown before Ortega arrested and charged him with first-degree murder. In that time Dallas County toxicologists had analyzed the “health pills” that Nancy said Richard had given her. Most were benign vitamin formulas, but two of the sixteen capsules contained pure barium carbonate—one of the toxic chemicals Richard had ordered in August.

On a cold Sunday in early March, four days after his initial interview with Ortega, Richard knocked on our door and asked to see my husband. Richard told him about the police investigation and said Bill Junior had filed a temporary restraining order to gain custody of his daughters. As my husband recalls it, Richard began hinting at a Dillard conspiracy—a family effort to pin Nancy’s death on him, to take away the girls. Maybe the hospital screwed up, Richard said, or maybe someone else killed his wife. As they talked, my husband sensed concern and fear in Richard’s voice but no anger at the apparent injustice of the police accusations. “He looked serious and shook up,” my husband later told me. “He looked more scared than outraged.”

Ayn Gaisford stopped visiting after that. Richard hired lawyers and was gone often. I started a journal. Three days after Richard talked with my husband, I sat in the back yard, struck by the stark contrast of two weeks earlier. Then, the yard had been full of life, with Allison, Anna, and Shawn running after the bunnies while Richard sawed and hammered and potted plants. “Now,” I wrote, “the plants have been strewn about, upturned by the wind or the rabbits. A light has been on for several nights in Richard’s tool shed. No one has been in to turn it off. The face of Nancy’s angel has streaks of light brown muck on it—sap, rusty water, bird crap for all I know. All life has gone, suddenly, except for the bunnies. Even they are thin, shaking, and hungry. Shawn and I feed them every day. Sometimes they run wild in the alley. The other night, their hutch collapsed in the wind.”

That night, I was awake in bed when Richard’s car pulled into the driveway. I heard his key in the door, his step on the stair six feet from my head. I felt, for the first time, a naked and nauseating fear.

Maybe it was Rosemary Lyon, Richard’s mother, who made me feel better. Within a few days she had left her job in Connecticut, moved in, and was washing and ironing his shirts, opening his mail, and cooking his meals. “I finally got him to eat something last night,” she said to me. “Now I can’t fill him up.”

Rosemary had a gritty, comforting, no-nonsense warmth about her. A second-generation Lebanese American, she seemed to be a woman who orders life by simple rules. She believes in the power of saints and is deeply loyal to her family and friends. I never heard her doubt Richard’s innocence. As she saw it, whoever killed Nancy was out to get Richard too. When she arrived, she emptied all of Richard’s spices in the trash. She looked warily at bottles of vinegar Nancy had kept above the sink.

Through Rosemary, I began to see Richard as a mother’s son. I found myself, once again, warmed to him, able to view him with uncertainty—a feeling that was far more comforting than the terror I had felt days earlier. My trust was still tenuous. One night Rosemary came to our door with a plate of apple pie Richard had made that day. I could never bring myself to eat it. Yet I remember, too, the beautiful, sunny, cool, windy afternoon when Richard and Rosemary came back from the first day of the custody hearing. I sat on the front porch while Richard complained about having to plead the Fifth Amendment on nearly every question, which his lawyers had advised. He said his stomach felt like it had “a hole in it” after he heard the Dillards’ testimony against him. “It hurts when you see your family, or what you thought was your family, saying you did something so horrible,” he said. He looked so sad, so sincere in his stated incredulities. In that moment, I felt genuine sympathy for him.

The Dillards never struck me as conspiring people. If anything, the manner of Nancy’s death left them stunned, outraged, and somewhat mortified. They were also scared. “I was sure that once Richard knew the jig was up, he would do something crazy, like kill the girls and then kill himself,” Bill Junior told me months later. “I had a lot of fear, a lot of fear.”

At the time, though, I didn’t know what to believe about Richard’s hints of secrets in Nancy’s family—secrets, he said, that tied into the mystery of her death. I found it hard to imagine. But by this point, nothing would have surprised me—or so I thought.

I hadn’t heard the testimony in the custody hearing. Richard’s lawyer had subpoenaed me as a witness, but after two days of waiting outside the courtroom, I was never called. Faced with no hard evidence proving Richard an unfit parent, the court gave the Dillards visiting rights but temporarily returned the girls to their father. After Richard and Rosemary returned, jubilant, from court that day, I knocked on their door. Richard ushered me in. He had loosened his tie; his face looked more relaxed than it had in months. He had seriously hurt the Dillards’ case, he said, by testifying about the incestuous relationship Nancy had had with her brother Bill while the two were adolescents.

According to Richard, Nancy first told him about the incest in late spring 1989, when they and other Dillard family members spent a “family counseling week” at Sierra Tucson, a psychiatric facility in Arizona, where Bill Junior was undergoing treatment for alcohol and drug abuse. While there, Nancy and Richard saw a sex therapist. The incest came out at that session, and as he said later, it left him “disgusted” and “repulsed.”

What actually happened between Nancy and her brother 25 years ago is disputed. After Richard’s trial, Bill Junior spoke to me frankly about it. There was never any intercourse, he said, and no one victim or perpetrator. He and Nancy cooperated in fondling games that confused physical closeness with emotional intimacy. The two had even talked forgivingly about it months before she died, he said.

But as I sat in his living room that day, Richard painted the ugliest of pictures: that Bill Junior would “pounce” on Nancy with advances she escaped by mentally withdrawing—by reading, in one instance, even as it happened. According to Richard, Nancy’s parents only discovered the incest when she complained of vaginal bleeding. I sat, speechless, at his descriptions. He looked back at me calmly. “Now you know,” he said.

That evening, when Richard drove his daughters back to the duplex, he got a police escort. Even though the day was wet, Richard brought out his guitar and began singing Raffi songs out back. The atmosphere was very festive, and it stayed that way for days. I remember, most clearly, one evening when Shawn brought out his toy guitar for another sing-along. Allison hung on Richard’s back, holding her blanket, while Anna played in the sand nearby. At the end of one song, Richard reached down and stroked Shawn softly on the cheek. For a moment, in that warmth, it was if the whole matter of Nancy’s death had disappeared.

We moved out six weeks later, into a house we had bought before Nancy died. In that time, we felt close to Richard. We shared dinners. When Anna was hospitalized with a rare viral syndrome, I watched how tenderly he cared for her. From time to time, Richard frolicked with my son. Their favorite seemed to be a tickling game, which Richard called “typing torture.” It always made Shawn giggle wildly.

Before we left, Richard gave us two bonsai trees. “Please keep these trees,” he wrote in a note, “as they will survive for decades with the same care that you give each other.”

We heard about Richard’s arrest in May. I felt helpless, seeing his picture on the front page. I went to his bond hearing and embraced Rosemary when his bail, originally set at $2 million, was reduced to $50,000. We didn’t see them much after that. We became, like so many who knew Nancy and Richard, intent on escaping the ordeal.

But escape was impossible. I had mistakenly taped the news report of Richard’s arrest on my son’s favorite Barney and the Backyard Gang videotape. I could barely listen to Raffi music. When one of the two bonsai trees died, I couldn’t stop seeing Nancy in its thin, withered trunk. And Shawn began having bedtime fears of men coming to “type” him. One night, months after we had moved out, I cradled him close and asked him, “Who types you?”

“Richard,” he answered.

The hallway outside state district judge John Creuzot’s courtroom was packed when I arrived on December 2 for Richard’s trial. It was an unusual scene from the start. For three weeks nearly everything in the courtroom, including the white-collar jury, masked the carnality of murder with a veneer of North Dallas propriety and aesthetics.

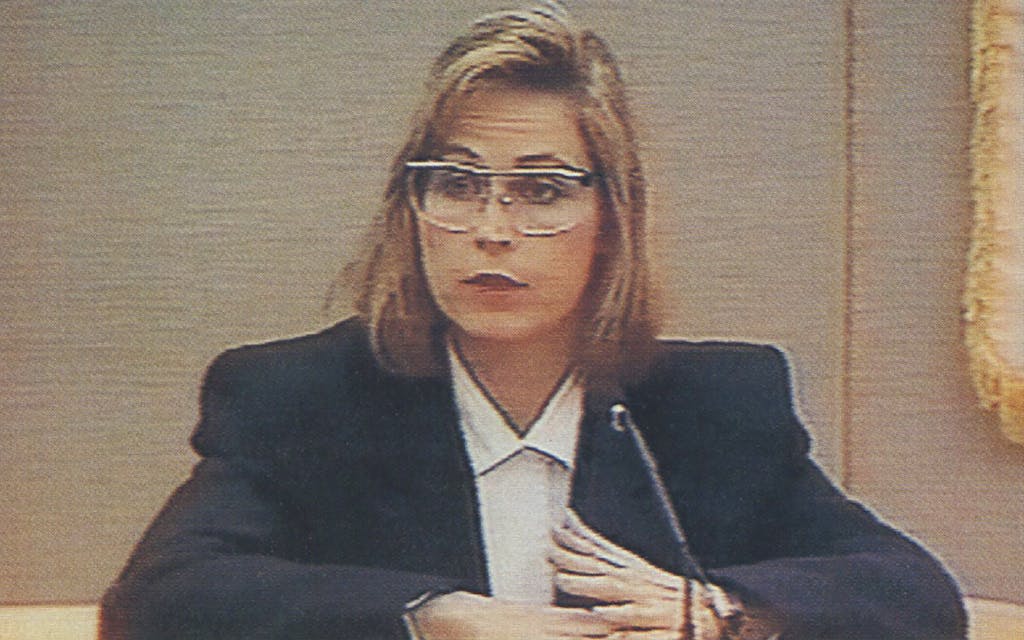

Richard appeared clean-shaven, in finely tailored suits, always carrying a briefcase full of legal pads and files. His lawyer, Dan Guthrie, a former assistant United States attorney with a reputation for defending savings and loan executives, was tall, handsome, and impeccably dressed. The state’s case was led by assistant district attorney Jerri Sims, whose elegant skirts, spiked heels, and waist-long blond hair effectively disguised her hard-nosed reputation for winning convictions. And each day, scores of well-scrubbed Dillard supporters came: elderly benefactors, young women with hankies pinned to their sweaters, Episcopalian ministers, ladies doing cross-stitch. Richard’s parents, and sometimes a friend or two, sat quietly apart from that crowd.

I sat with the journalists, believing I could watch Richard’s trial with their dispassion. I acted the part well, recording every minute of testimony in my little notebooks. Only later did I realize that I had never been dispassionate.

I had hoped Guthrie would show me that his client didn’t kill Nancy. He had pledged as much in an unusual press conference nine months earlier, which he called after University Park police named Richard as a suspect. Then, Guthrie declared Richard innocent and promised that if the case went to trial it would be a “real Perry Mason whodunit.” I was hoping it would be, I suppose, for the same reasons I had continually denied Richard’s guilt. It wasn’t just my belief in his right to a fair trial. I also didn’t want to admit that I had put my faith in a man who had coldly killed his wife.

What I saw instead was the state’s carefully-laid-out case, which implicated Richard at every turn. In testimony from Nancy’s father, her doctor, Detective Ortega, and others, the state fashioned a picture out of her suspicions of Richard, Richard’s apparent lies to the police, the autopsy report, the health pills packed with barium carbonate, and the paper trail of chemical purchases that ended with the December arsenic delivery. I was stunned, too, by the testimony of a man who, in January 1991, repainted and cleaned the apartment Richard had lived in while he was separated from Nancy. Among Richard’s belongings the man saw several empty clear gelatin capsules—the same as those containing the two tainted health pills. There was also the subsequent tenant at the apartment, who testified that while cleaning the back of a bathroom cabinet, she found a prescription bottle in Nancy’s name. Along with the pills inside were two antibiotic capsules laced with sodium nitroferricyanide—another poisonous chemical that Richard had bought from General Labs in August 1990.

Money, not just his romantic liaison with Ayn, appeared to be the motive. Nancy was worth about $1.2 million, including $500,000 from her life insurance policy. Four months before her death, she had removed Richard as beneficiary, naming her children instead. The children’s nanny, Lynn Pease-Woods, had signed as witness to the change. According to Lynn’s testimony, it seemed as if Richard didn’t know about the switch, even after Nancy’s death. The defense’s attempts to counter Lynn’s testimony looked suspicious. Guthrie introduced a typewritten note, addressed to Richard, dated November 1, 1990, and signed “Nancy,” which mentioned the beneficiary change. But Lynn testified that Nancy didn’t know how to type and even took pride in that fact.

Through his cross-examination of other state witnesses, Guthrie deluged the jury with a muddle of doubts. He suggested other suspects: Bill Junior, for instance, or Nancy’s former boss at Crow Development, David Bagwell, who had been sued by the Crow companies for misappropriating $720,000. Nancy had been a potential witness against Bagwell and had received a death threat relating to the case in 1989.

Guthrie also hinted at suicide. But that scenario seemed unlikely when the state introduced a nine-page letter from Nancy to Richard, written four months before her death in powerful, intelligent, eloquent prose. When read aloud, it was as if Nancy’s voice had suddenly come into the courtroom to state her own case:

“My nature has always been to be so optimistic, so positive, so charged up about my life, and over this last year, in losing what I valued most in my life, I have let myself be so consumed by fear, unhappiness, heartache, and misery that I have compromised my values and principles and lost sight of myself, my needs and my dreams . . . I can see clearly that the children and I need and deserve so much more. They need a loving, consistent parent who is there for them day and night . . . They need stability and predictability and a promise that no matter what, they will be defended, protected and safe, every moment, every day . . . I no longer have any desire to hold you to your marriage commitment. Not only are you free to go, but I need to demand that you go before even more damage is done to the children and to me.”

I watched Richard cry as the letter was read. I will never believe, as some suggested, that his tears were just a ploy to win the jury’s sentiments. But I could feel my focus changing. I no longer wondered if he had killed her. I wondered, instead, what twisted passion had carried him through the months of premeditation, through the hours of her retching at home, through the days of her decline and death. I cannot pretend to know what happened between Richard and Nancy, but I believed then, as now, that Richard loved her once—as deeply as he must have grown to hate her.

On the day the state rested its case, Richard came over to me in the courtroom. He asked about Shawn and told me about Anna’s funny antics. As we talked, I had trouble looking into his eyes. I could feel the Dillards’ friends staring at us. When he asked how I thought the trial had gone, I shrugged and said nothing. “Just wait,” he told me. “All the facts will come out.”

When he took the stand two days later, Richard never denied ordering the arsenic. He said he bought the poison to kill fire ants at the duplex and at a job site. Although his testimony drew snickers of disbelief that his supposedly all-organic company would sanction arsenic as a fire ant control, I knew the duplex had an ant problem. In late summer 1990 it had gotten so bad that I asked Nancy about it. “Richard’s working on something,” she told me. As Richard described it, he planned to bore into the mounds and then spray poison. Nancy had worked with him on the scheme, he said; in fact, it was Nancy who suggested buying arsenic in the first place.

Richard’s testimony also put him 250 miles from Nancy during the hours on January 8 when she would have gotten the fatal dose of arsenic. Airline tickets, restaurant receipts, and eyewitnesses all confirmed that he had been in Houston since early that day and had arrived home around six, about the time Nancy began feeling sick. He portrayed his wife as a vulnerable, sickly woman. All through the fall of 1990, he said, Nancy had called him often, complaining of illness. Her calls always drew him back to the duplex, he said, to check on the children or to help her.

As proof he offered writings he said were Nancy’s—pages of notes, which Richard said he found in a file box three months before the trial. Nancy had been in counseling nearly all of her final year. I knew she wrote often about her therapy; once, I had seen the walls of her bedroom covered with sheets of paper. Two pages offered by the defense particularly played into suggestions of suicide or other suspects. One described how Bill Junior had incestuously “violated” Nancy for years, how her family had denied it, and how Richard had tried to help her—“tried to save me,” the note said, “with his sincere heart and his unending patience with my ‘hang ups’ about sex.” On the bottom of another page was written, “fears of bill and what his desires are—sex—sick sex-incest issues with me?—my girls?”

The defense had hired a handwriting expert, who had said the writing was Nancy’s. Later, they would put on the stand James Grigson, the psychiatrist known as Dr. Death for his controversial death-penalty testimony. Solely on the basis of the notes, Grigson described Nancy as deeply troubled, calculating, controlling, and manipulative. He suggested that she had made herself sick with poisons to lure Richard back to the marriage.

By itself, the theory seemed preposterous. Arsenic poisoning is a painful, prolonged, and agonizing way to kill oneself. What’s more, Nancy hadn’t acted one bit suicidal in the weeks before her death. She made her usual Christmas gifts and planned trips for the coming year. Her daughters seemed far too important to her. And why would she have cried out for help in the hospital if she had known, all the while, what was killing her?

Then Guthrie produced the receipt. It was dated September 6, 1990, from a company called Chemical Engineering in Dallas. It listed purchases of four chemicals: barium carbonate, lead nitrate, cyanogen bromide, and arsenic trioxide. It was signed “Nancy Lyon,” with her driver’s license number beneath her name.

As Richard stood before the jury, pointing to a blowup of the receipt, the change in the courtroom was physical. He testified that he had found it stashed in the same files with her private writings. For the first time during the trial, Rosemary leaned forward and tried to catch my eye. “Can you believe it?” she mouthed.

It was hard to know what to believe, particularly when the president of Chemical Engineering, Charles Couch, testified later that his firm specialized in recycling old carpeting. But Couch, a large man with a cocksure manner, also acknowledged he was “known in the business” as someone who could devise chemical formulas. In September 1990, he testified, a woman had called him to discuss fire ant poison. According to Couch, the woman never identified herself, but she told him that she and her husband were trying to inject poison into the mounds with a long drill. When Couch offered to look up a formula for her at the Southern Methodist University library, the woman asked if he could drop the notation by her house—which, she said, was right next to campus, as our duplex was.

Couch testified that he did look up a formula, which matched the items on the receipt. But he never dropped it off. Instead, the woman apparently came to his plant the next day to get it. He testified that that he never saw her: He was on the phone in a back office at the time. Through one of his employees, he passed on the formula, which he had jotted on notepaper with his company’s logo. But Couch called the receipt a forgery. It had no invoice number. It was typed, while all his are handwritten. And, oddly, it had a notation to call Keith or Charles on the bottom—names of contractors who transport huge quantities of chemicals for the company. Couch said he remembered inadvertently jotting their names on the bottom of the notepaper with the formula right before the woman came to pick it up.

Yet even if Richard had forged the receipt, it was hard to explain the call Couch had gotten. Equally puzzling were the results of additional forensic tests on Nancy’s hair, which the medical examiner’s office had requested in May. Bundles of the hair had been sent to Vincent Guinn, a chemist at the University of Maryland, who uses a technique called neutron activation analysis to detect various chemicals in hair. Before analyzing the hair, Guinn had sliced it into tiny segments, each representing roughly two weeks’ growth. The results showed that in addition to the lethal dose in early January, Nancy probably had ingested arsenic at least two other times before that: a sizable dose sometime between mid-December and New Year’s Eve, and a much smaller one in mid-November. Both were before Richard could have received the arsenic from General Labs.

There were theories to explain the evidence. Richard might have gotten arsenic elsewhere. Maybe Nancy’s hair grew faster than normal. Maybe shellfish or hair coloring caused the small November dose. Yet the autopsy also showed Nancy’s fingernails had at least five times more arsenic than her toenails—a result that suggested she might have handled the chemical, either by touching poisoned food or the arsenic itself.

Two days before the end of the trial, it seemed Guthrie had achieved reasonable doubt. That day, Shawn visited me at the courthouse for lunch, and Richard chatted easily with him in the hallway. As I watched, it seemed that more harm would come from a conviction than from an acquittal.

I lost all faith less than two hours later. On rebuttal, the state produced Hartford R. Kittel, a retired document examiner from the FBI. Unlike the defense’s handwriting analyst, Kittel compared all writings in evidence not just with Nancy’s known samples but also with Richard’s.

I had always marveled at how similar Richard’s and Nancy’s handwriting was. In graduate school, I later learned, they had actually worked to make their writing look alike for design projects, giving it the same angular n’s, the same long loops below their g’s and their y’s. But Kittel pointed out their differences. Richard’s i’s were a straight line down; Nancy’s were framed by little cross lines. Richard’s f’s sometimes had a backward loop; Nancy’s never did. Nancy’s s’s were always serpentine; Richard’s were sometimes scripted.

And then I saw how, in the most powerful of Nancy’s personal writings—in the pen scratches that spelled out “Bill violated me for years,” “sick sex” and “Richard . . . with his sincere heart”—in nearly every word that damned Nancy, there were Richard’s handwriting peculiarities. To my eyes, the call wasn’t even close. Kittel also questioned the authenticity of the signature on the insurance note and couldn’t identify the one on the receipt from Chemical Engineering.

The jury returned its verdict less than three hours later. As the courtroom doors opened, I saw an ashen Richard looking back at the crowd filing in. When the foreman read, “Guilty,” Richard’s eyes widened. Then he stared straight ahead, hung his head, and sighed.

“I can’t believe this has happened,” he told Guthrie minutes later, as they sat in a holding cell. “I’m innocent.” Outside, amid a flurry of television cameras, the Dillards were whisked away. In the emptiness that followed, journalists milled the halls, looking for someone who would comment on the case. I walked toward the elevators and left.

Soon I was driving up Central Expressway in a pouring rain. As I had done so often in the years before, I turned off at Mockingbird and zigzagged past SMU to the duplex. The shutters were drawn. The Christmas lights were hanging in the same loose way as the year before, when I had taken them down as Nancy lay dying. Sitting there in my car, it seemed absurd that after all these months, my doubt about who killed Nancy should have fallen apart based on the shape of an i, an f, and an s. But that was all it took. Mere markings of a pen had become, for me, the desperate imprints of a very convincing liar.

On New Year’s Day, I went to see Richard in jail. He wasn’t expecting me. I didn’t quite know how to alert him that I was coming, so I simply showed up. Richard entered on the other side of the bulletproof glass dressed in white jail overalls. An orange ID band encircled his wrist. He looked pale but lively. He sat down easily and picked up the phone. He looked as even-tempered and pleasant as I remembered him. There was no desperation in his voice or face.

“How are you doing?” I asked.

“Not great,” he said. “But we’re working on getting a new trial now . . .” His talk quickly moved into a litany of reasons why he should have been acquitted, especially with what the forensic evidence showed. “You tell me how I could have given her those prior exposures,” he said. “You tell me, and then I can sit in a jail cell and think about it. But you can’t tell me. That’s reasonable doubt.”

I was blunt with him. The handwriting analysis had hurt him. So did his apparent lies to the police. And it simply didn’t make sense that Nancy would beg for help in the hospital if she had killed herself. “I don’t understand it either,” he said. “I lived with her, and I don’t understand it. All I know is that she bought arsenic. That receipt is real. . . . Why would I forge that stuff?”

As he talked, he looked me straight in the eye, and I found myself searching his pale green irises for some hint of the truth. All I saw was calm, logical analysis. He had an answer for every question. The thought crossed my mind, at one point, that Richard is either delusional, thoroughly evil, or innocent. And at that moment I really could not tell which it was. “You know me,” he said. “You know I would never do anything to hurt the girls. I would never have taken away their mother. Why would I need to kill her? I would have walked away from the marriage.”

I was hoping my visit would give me some closure to the matter of my neighbor’s death. It did not. What was I expecting, after all? That Richard would suddenly break down, confess, set forth the story without ambiguity, allow me to walk away that night satisfied that at least I knew the whole wretched truth? Instead, as the guard came to get him, Richard left me with this: “I can only pray that the truth will come out someday,” he said, “because it didn’t at the trial.”

I cannot say Richard Lyon killed his wife beyond all possible doubt. Like the jury, I believe he is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, but my knowledge will always be in fragments, like the glimpses I had during the years I lived under his roof, like the pieces of evidence that became the court record.

Or, as I thought driving back from the jail that night, like the way I saw his eyes shift downward only twice during my visit with him.

The first time was when I asked about his daughters.

The second time was when I suggested that maybe Nancy got her poison in the Zovirax capsules she had been taking at the time.