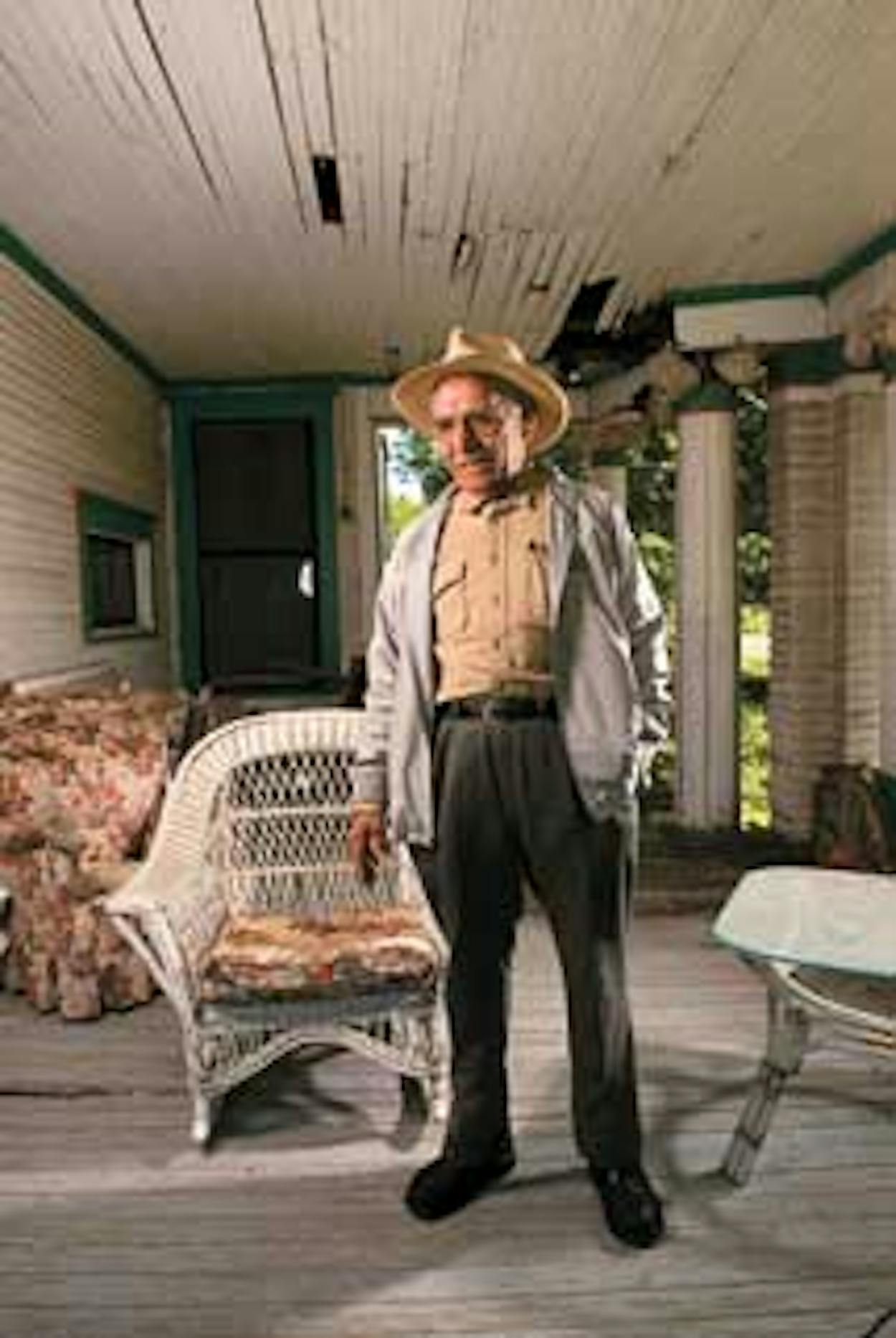

Pete Dominguez eases his rattletrap Chevy Malibu into the driveway of the old house in Wills Point. “Here we are,” he says cheerfully. “Home.” The house was a showplace when he bought it, in 1970, but now it’s literally falling apart—paint is peeling from the Greek Revival columns, one corner of the wraparound porch has collapsed, and the roof looks as if wolverines have camped there. Pete paid cash for it, $10,800, which was little more than pocket change for the young and energetic impresario of a burgeoning chain of Mexican restaurants. That was then. Now he struggles to pay off a mortgage of more than $100,000, a debt incurred in one last, futile effort to save his failing business. Once, Pete Dominguez was the toast of Dallas. But at 68, he is alone, broke, and nearly forgotten. “I used to think I’d come out here and retire,” he tells me as we step gingerly across some broken boards and into the foyer. “Yeah, I’m retired all right.” This is said without bitterness or rancor but with a melancholy acknowledgement that irony is the worst of life’s aimless jokes.

The floors are littered with piles of old clothes, magazines, and assorted trash, telltale signs that there hasn’t been a woman around for a long time. Pete’s second wife, Graciela, divorced him years ago, no longer willing to tolerate his drinking. His mother used to stay here from time to time. You can see her touch in a shrine to Our Lady of Guadalupe in one of the downstairs rooms. At 88 she’s mostly confined to a rest home in Austin; the grand house that Pete purchased for her years ago fell victim to his mounting debt a while back. Same thing with his 220-acre farm near Wills Point. They’re all gone, all except this house, which is in the late stages of going. One by one, he lost his restaurants; there were nine of them. Pete filed for Chapter 13 individual bankruptcy protection last year, but the protection never went through because he failed to send in his tax returns. At the time of the filing, his debts amounted to $330,000. More than $50,000 behind in rent, Pete sold his final restaurant, Casita Dominguez, last December, for a token $5,000. Since then he’d been looking for work. He was willing to do anything, he told me—walk dogs, clean bathrooms, cut grass. A few days before my visit, in late March, he’d found work scrubbing restrooms and doing odd jobs at the Canton Marketplace, a flea market about fifteen miles southeast of Wills Point.

I follow him up a narrow, hand-carved staircase installed in 1914 by the original owner, a lumber baron, to a suite of bedrooms, their doors closed. The ceilings are water-stained and caving in. The house isn’t air-conditioned, and the only heat comes from a small space heater, which Pete moves from room to room. He doesn’t use his upstairs bedroom anymore, preferring to sleep on a worn sofa in a downstairs parlor, in front of an old TV, near a phone that seldom rings. In one of the upstairs rooms, Pete finds what he’s looking for: packing boxes full of framed photographs of sports stars and celebrities that once hung on the walls of his restaurants. Dozens of other pictures and mementos were consumed by a fire that destroyed his flagship place, Casa Dominguez, in 1992.

“That fire was the beginning of the end for me,” he says, removing the pictures from the boxes and spreading them across the bed. Authorities called the blaze “suspicious,” but blame was never assigned. Though Casa Dominguez was later rebuilt at another location, it wasn’t the same.

Pete is smaller than I remember, his thick nest of hair gone silver, his quick dancer’s step beginning to falter. How long had it been? Twenty-five years? Thirty? I know we first met in the fall of 1963 (my God!), just after he opened Casa Dominguez. I was working for the Dallas Morning News and Pete had moved to town six years earlier. He grew up in Manchaca, near Austin, one of five children born to a cowboy-farmer and his wife. Dropping out of school after the seventh grade, he’d taken a series of jobs washing dishes and busing and waiting tables at Mexican restaurants in Austin and later in Dallas. He’d married his first wife, Mollie, in 1958, and they had had two sons, Mark and Adrian. The original Casa Dominguez was a hole-in-the-wall on Cedar Springs Road, north of downtown, that advertised “Austin-style Mexican food.” That’s what attracted Bud Shrake and me and a couple of other newspaper types. Turned out to be the best Mexican food we’d ever eaten. Pete served us, then sat down and had a beer and talked. We liked him instantly. He had less than $60 in the cash register but insisted on picking up our check. Bud wrote about the new restaurant in his Dallas Morning News sports column the next day, and that night the joint was packed. “We ran out of food,” Pete remembers now, his smile large but sad. “You guys made me.”

No, the truth is Pete made himself. The recipes came from his chef, an acquaintance from his Austin days named Marcello Montez—all except the pralines, which Pete prepared using his mama’s recipe. But what made Casa Dominguez the hottest spot in town was Pete, that mile-wide smile greeting you at the front door, that willingness to please, to be your friend. In no time, Pete knew everyone and everyone knew Pete. A whole generation of Dallas Cowboys became regular customers and friends too— Meredith, Gent, Lilly, Harvey Martin. Pick a name and I promise you he ate there. Cowboys owner Clint Murchison Jr. did, as well as other Dallas swells. Pete was especially partial to sports heroes. Lee Trevino and Darrell Royal became close friends; Royal was even the best man in Pete’s second wedding. Over time celebrities like Clint Eastwood, Carol Burnett, and Princess Grace of Monaco feasted on Pete’s brand of Tex-Mex and posed for photographs. Invariably, Pete was in the picture, grinning like the Cheshire cat.

Pete’s generosity was so unfailing it could be embarrassing. Friends learned that if they expressed even a casual interest in something Pete owned, he’d give it to them on the spot. He gave Trevino a vintage Ford pickup, and no matter how ardently Trevino pleaded that the gift was excessive, Pete wouldn’t take it back. He gave Bud a horse, which was about the last thing Bud needed at the time. When I remind Pete about that gift, he tells me, “Yeah, Bud never did come pick that horse up. He finally got old and died.” As the business grew and expanded, everyone in Pete’s large, extended family came to depend on him. Nearly three dozen relatives were on the payroll of one of the restaurants, including Adrian, Mark, and Pete’s younger brother, Frank.

After kicking around the house awhile, Pete and I decide to eat lunch at Paco Dominguez, a Mexican restaurant that Frank opened a few years ago in downtown Wills Point. Before he got the flea market job, Pete helped clean up at night in exchange for supper. Some of his old photos now hang on the walls. Over iced tea and enchiladas, we recall our misadventures as young men. Pete asks if I remember the night at Casa Dominguez when, after numerous shooters of tequila, I agreed to give him a tryout for the Cowboys. “Yeah, you claimed to be a better receiver than Buddy Dial,” I remind him. “After the place closed, we moved some tables aside and you ran some routes.”

“And you used a wet towel for a football,” he says, laughing.

I nod and tell him, “You weren’t half bad.”

Pete’s Walter Mitty impulses were irrepressible, not that his newspaper pals tried to discourage them. Dallas Times Herald columnist Dick Hitt arranged for Pete to go three rounds with Curtis Cokes, who was at the time welterweight champion of the world. The gate went to charity. Another time Pete rode a bull at the rodeo arena in Wills Point. “I was wild and crazy back then,” he concedes. Full of piss and vinegar, tequila and beer.

As I say, Pete drank a bit. We all did, but his got out of control. He could be erratic and irrational, a handful for friends and a problem for employees and police. At the Dallas premiere of Bud’s movie Kid Blue (1973), Pete showed up waving a gun and babbling that he had reason to suspect that someone was planning to steal the print. Meanwhile, a struggle for power inside the Dominguez family was poisoning the atmosphere. Pete believed that Adrian, who had studied restaurant management at the University of North Texas, was trying to muscle him aside. Adrian had his head full of hotshot ideas put there by some professor, and this drove Pete crazy.

“He wanted to add salads and put strawberries and stuff on the side of the plates,” Pete complains. “What did some college professor know about running a Mexican restaurant?”

Apparently the drinking got worse after I left Dallas, in the late sixties. I learned later that between 1974 and 2001 he was arrested six times for driving while intoxicated. The accumulation of arrests cost Pete his liquor license and led to a family mutiny in which Adrian took over the business and essentially fired Pete. Without Pete, of course, there was no business. That was a lesson they didn’t teach at North Texas.

Pete assures me that he hasn’t had a drink since February, and I take him at his word. Nevertheless, I can tell that retirement is eating at him, savaging his pride. Naturally gregarious, he is alone for the first time, frightened, confused, unsure where to turn. A few old friends are trying to help, including a group of retired Dallas sportswriters who stay in touch. Walt Robertson, once the sports editor of the Morning News, showed up at Pete’s house not long ago with a brand-new lawn mower, a replacement for the ancient relic in Pete’s garage. Someone else helped pay for repairs on the Chevy Malibu. Someone tipped off the Morning News and on March 16 the paper ran a story chronicling Pete’s problems.

For the present, at least, Pete has no choice but to keep a low profile. When he applied for a job scrubbing floors at the Canton Marketplace a week or so before my visit, he didn’t offer a résumé or hint that he had once owned a chain of restaurants. “We didn’t know who he was until a story ran in the Dallas Morning News,” says Barbara Moore, who, with her husband, Virgil, manages the huge (93,000 square feet) climate-controlled shopping barn, a centerpiece of Canton’s famed flea market, the largest of its kind in the world. More than three hundred vendors rent space at the marketplace. On Thursday through Sunday before the first Monday of every month, hundreds of thousands of visitors crowd the streets of Canton. When the Moores discovered that their new employee was not merely an uncomplaining worker but a first-class Mexican food impresario, they turned over part of the kitchen and gave him free rein to do his thing. Well, almost free. They did veto Pete’s initial idea to call his menu “Hill Country food.”

“He’s the best thing that ever happened to us,” Barbara tells me. “This is the best Mexican food we’ve ever had. A friend ate four pralines! Pete is a celebrity and doesn’t even know it.”

Oh, Pete knows it all right. I hope that doesn’t turn out to be a problem. I hope he stays off the sauce, because he clearly can’t handle it. It will take a long time to pay down his debts, but Pete has faced large challenges before. If the old house doesn’t burn or fall on his head, I’m betting he will make it.