Last January, as Maury Maverick, Jr., the legendary Texas liberal, lay dying of kidney failure in a San Antonio hospital, a small group of us—including his wife, Julia—stood near his bed, listening to his raspy, labored breathing. He was 82 and not yet ready to die. “I’m dying,” he’d told me a few days before, “and I don’t know what to do about it.” There it was: the whole truth, blurted out from his deathbed, with his eyes wide open and his fists clenched. Bravery was a sharp instinct with Maury, part of his DNA, and it was with him until the end.

Standing over him in the hospital, I was unable to separate any aspect of my own personal or professional life from his illuminating and at times lacerating influence. In my mind, Maury was Don Quixote and I was Sancho Panza. But his influence was more than mythic. The flesh-and-blood Maury was a constant presence. I named him an official “bridesmaid” at my wedding in 1981. During the service, he stood under a live oak tree and gave a speech about the importance of fighting for personal liberty, even—in fact, especially—in marriage. I named my daughter Maury, hoping to give her some of his courage.

Now he was dying, the last of a political archetype—the real Texas Mavericks. Anglo liberals like Maury have long held a fragile stake in Texas. In San Antonio, where Mexican Americans outnumber Anglos and Catholics outnumber Protestants, that stake is largely demographically driven. The kind of evangelical conservatism that you find in East Texas and in the suburbs of Dallas and Houston just doesn’t hold much sway. As a state legislator in the fifties, Maury supported the right of blacks and Mexican Americans to vote and of unions to organize. Crafty, contrarian but never cynical, he studied the Constitution the way other people study their horoscope: for fun. Consequently, anyone who thought of himself as down-and-out, put down, or picked on felt that Maury was his special ally. But times have changed in San Antonio, just like everywhere else. Unions don’t have the power they once had. Minorities now speak for themselves. In San Antonio today, there is not a single Democratic politician of promise under fifty who is an Anglo. Maury was old and eccentric enough to ignore the new rules. He kept right on speaking out for labor and minorities as if it were still the fifties, and no one seemed to mind.

Maury was not by nature a nurturing man. Years ago his mother, Terrell Maverick Webb, described his father to me as “gently rough and roughly gentle.” The same was true of Maury. If he and I went longer than a week without an argument, he couldn’t bear it. He’d be on the telephone, needling me until I gave him the fight he longed for. Often, these provocations would begin when Maury telephoned and identified himself as Sam Houston, up from the grave.

“Child, this is Sam Houston, speaking to you from heaven,” Maury would say, putting on his best Houston voice. “I demand to know if anyone in your family ever did anything as brave as I did in 1861, when I begged the people of Texas not to secede from the Union.”

“No, Mister Sam, they did not,” I would respond obediently.

“Well then, get busy,” he’d snap. “Stop writing for the swells. Write for the poor and the oppressed, the people who need liberty and groceries.” In today’s Texas, who would think to invoke the name of Sam Houston to give a lecture about not writing for the swells?

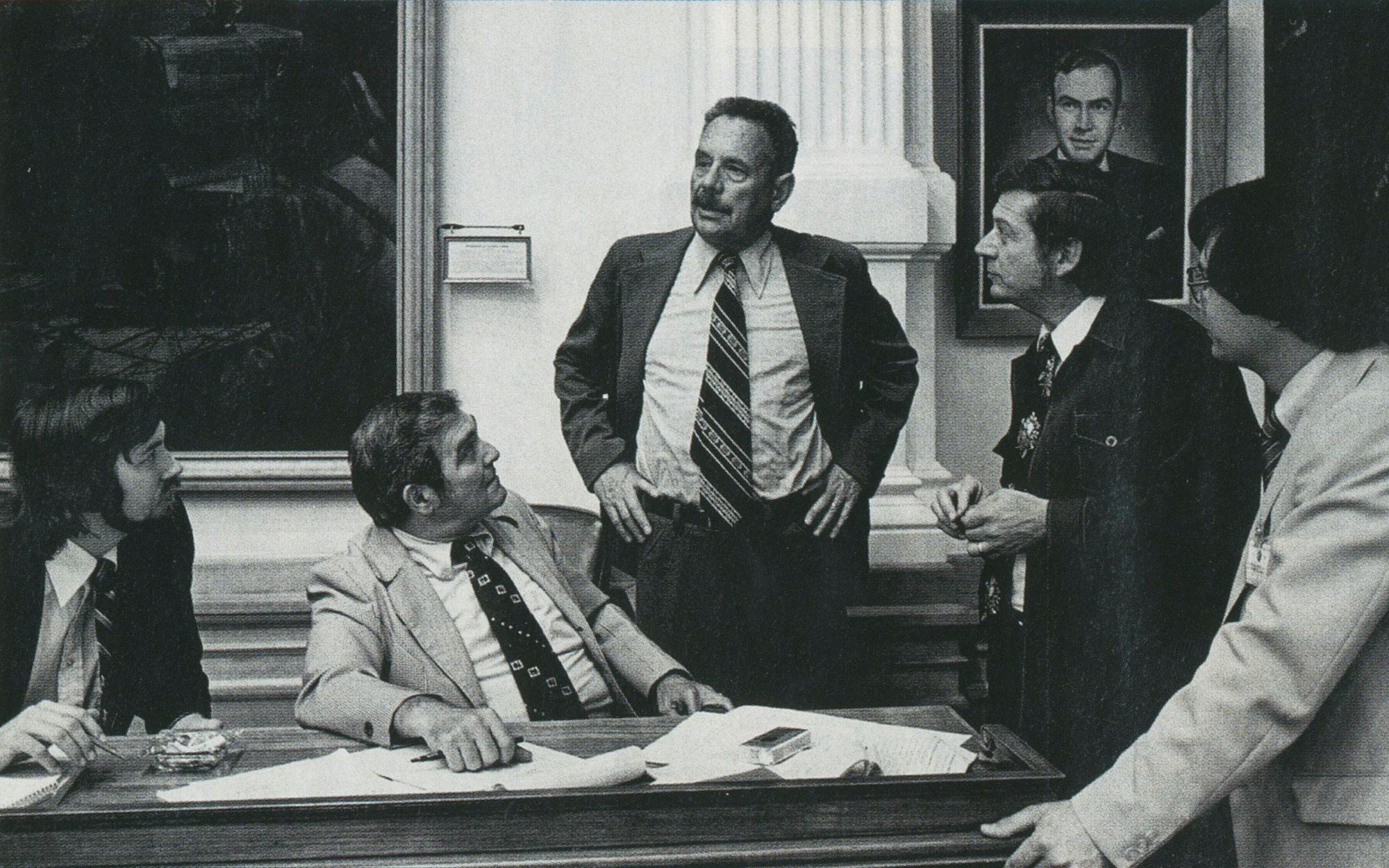

I first met Maury in the Spring of 1973. I was 22; he was 52. I took him to lunch at a health-food restaurant on the Riverwalk, a place called the Greenhouse that no longer exists. I was green myself, a young reporter for the San Antonio Light working on a story about Maury. At the time, he was best known as a red-hot liberal, the state’s celebrity civil-rights lawyer, a former member of the Texas House of Representatives who in the fifties had successfully opposed a bill calling for the execution of Communists—and, well, a maverick, in disposition as well as name.

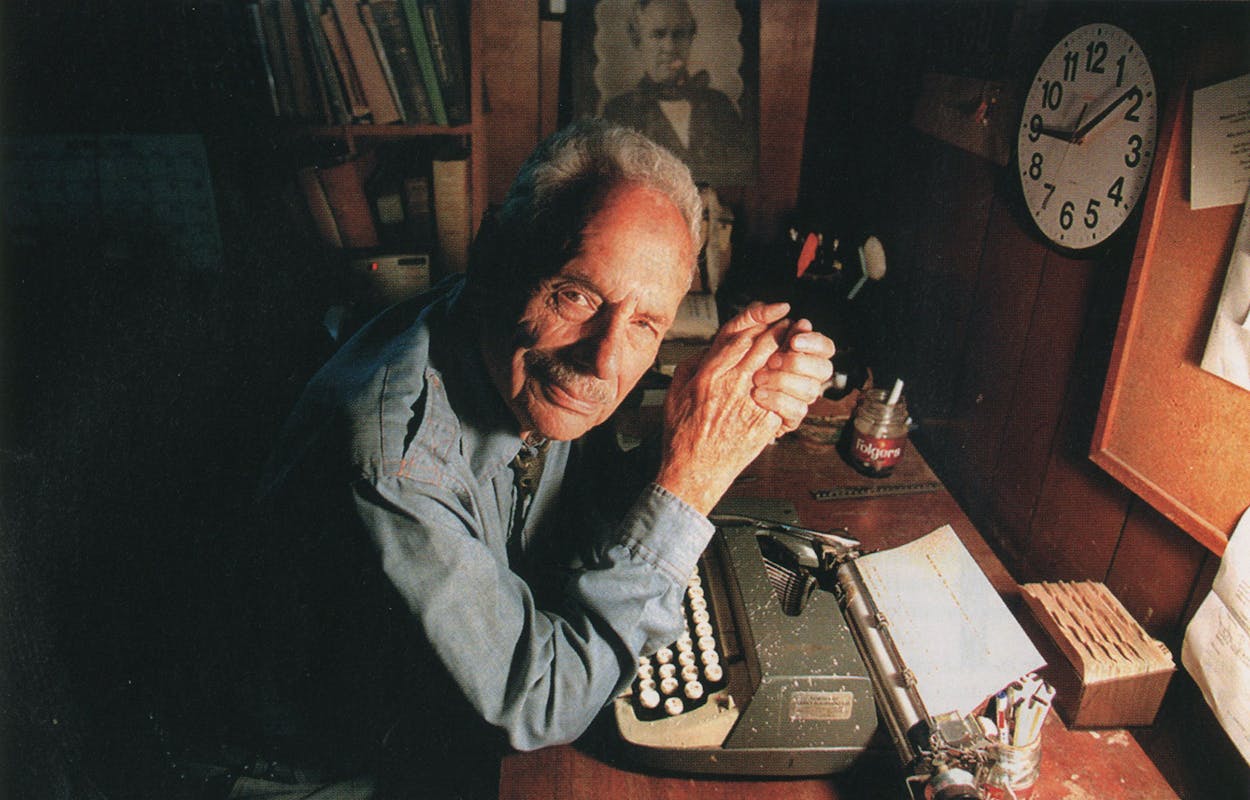

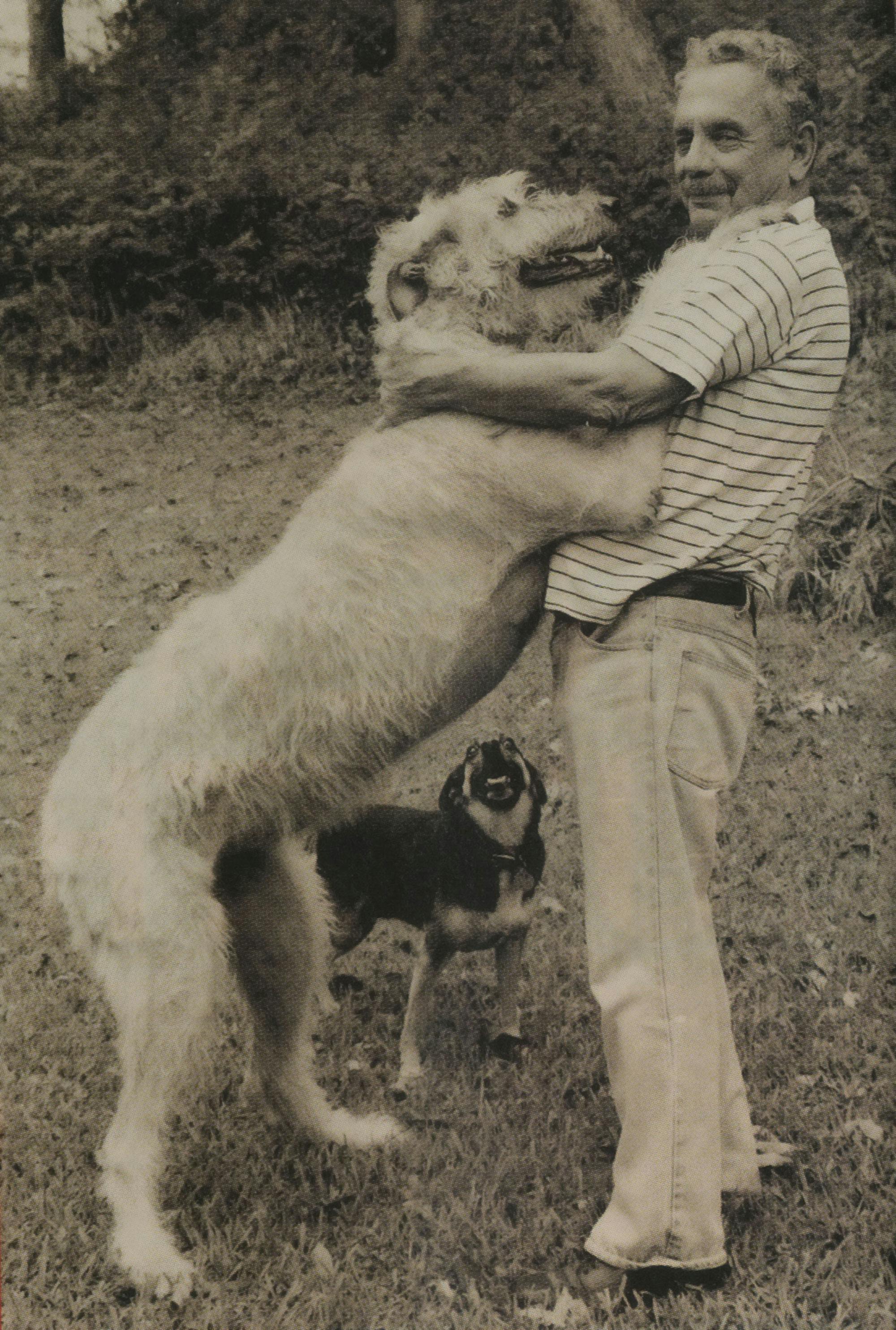

He arrived at the restaurant wearing a dark velour shirt with a hole in it, a bolo tie, and wrinkled gray pants. His mustache and hair were still mostly dark, although there were sprinkles of gray. His face was deeply lined, especially around the mouth. I still remember how he smelled: of wet dogs, fresh earth, burned coffee. He seemed ancient.

For most of the afternoon, I sat rapt, mesmerized by stories that are now part of Maury’s official canon. He talked a lot that first day about his experience, between 1951 and 1955, as one of the few liberals in the Texas Legislature. When a resolution was introduced to invite U.S. senator Joe McCarthy, the Wisconsin Republican who had led the witch-hunt against Communists, to speak to the Legislature, Maury offered an amendment to invite Mickey Mouse instead. “If we’re going to invite a rat,” he said, “why not invite a good rat?”

What I remember most about that first lunch was how thoroughly Maury was dominated by his deceased father, Maury Maverick, Sr., the New Deal congressman and San Antonio’s most progressive mayor. He told the story of what happened the day the Texas House considered a resolution to investigate Clarence Ayres, a University of Texas economics professor, for challenging some of the theories of capitalism. When it came time to vote, Maury Junior hid in a men’s-room stall so the House page wouldn’t be able to find him for the vote. The Legislature had become a mob of red-baiters, and Maury was afraid. The next day his father telephoned and said he hadn’t seen Maury’s name in the newspaper as voting against the Ayres investigation. Maury told him he’d been hiding in the restroom. “Goddammit, boy!” shouted the senior Maverick, “I won’t have any shit-house liberals in my family!”

Maury’s need to confess this single lapse of courage struck me as absurd. But it was my first lesson in what it means to be a Texas liberal. Texas is a state that clings to the exploitative values of the South even as it mythologizes the every-man-for-himself values of the West. In such an innately conservative place, liberals aren’t limited by any possibility of victory, so compromise is out of the question. Because the pursuit of liberalism often becomes the pursuit of political purity, the odd truth is that Texas liberals can never be liberal enough.

To find the roots of Maury’s liberalism—and perhaps to understand why Texas liberals equate courage with being outnumbered—you have to go to New England. I realized this one cold spring day in 1984 when Maury came to see me in Boston, while I was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard. Together, the two of us visited the grave of Samuel Augustus Maverick—a distant cousin who, in 1770, at the age of seventeen, was one of the first five men who gave their lives for this country at the Boston Massacre. When we came upon the grave, Maury was very moved, and he leaned against his cousin’s tombstone and wept. By then it was snowing hard, and the tears froze on Maury’s face. Finally, we made it across the street and into the warmth of King’s Chapel, where we sat in a pew and thawed out. “God,” he whispered, “it just takes a few people to change history, doesn’t it?”

The idea that heroes go against the grain, even unto death, was central to his view of what it means to be a patriot. He learned this lesson from his ancestors, including his great-grandfather who was also named Samuel Augustus Maverick; the first Maverick to come to Texas, he arrived in the 1830’s, when Texas was still part of Mexico. Maury’s father often told him that his great-grandfather, a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, was taken prisoner by Mexican troops in 1842 and marched to a prison south of Mexico City, where he was held in chains. After he was released, he brought the shackles back to Texas. The memory of his father fingering those shackles stayed with Maury all his life. Some days his father would wave them in his face and, pretending he was on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, bellow to his son, “Will the gentleman yield for an observation on liberty?” The “gentleman”—little Maury—never failed to yield.

In addition to the shackles, Maury’s great-grandfather left him the legacy of his famous name. After the Texas Revolution, Samuel Maverick became a wealthy landowner. He left his herd of Longhorns unbranded, and the cowboys would call a stray from the herd “one of Maverick’s.” In time, the word “maverick” became synonymous with those Longhorns and their owner—unbranded, obstinate, and utterly independent.

Maury was born in San Antonio on January 3, 1921. His early memories were of being with his parents and grandparents on the family’s Sunshine Ranch, north of downtown. There, at least, liberals enjoyed a rare consensus. Maury’s father did early battle against the Ku Klux Klan, which he nicknamed the Koo Klucks Kondemned. He saw his political career come to an end in 1939, when he gave Emma Tenayuca, an organizer for pecan shellers, permission to hold a rally for the Communist party in the Municipal Auditorium. A mob of five thousand protesters stormed the auditorium, and others surrounded the Maverick home as well. Maury, then only eighteen, and his parents hid at the home of a friend of the family.

All of this left its mark on Maury. In 1954, when his dying father told him that he must use the notoriety of his name to speak up for liberty and social justice, Maury vowed that he would.

Sometimes, however, he complained of the burden of the name. Occasionally, when a stranger he encountered on the street in San Antonio called out to him, “Mr. Maverick, do you remember me?” he’d flinch and mutter under his breath, “No, you son of a bitch.” A loner, he was shy in the extreme. He preferred to spend evenings in his rock house on Bellview, just south of downtown, eating a quiet meal with Julia and going to bed early—with his four dogs. (That’s an image I now cling to: Maury safely tucked under the covers with his dogs.)

But despite the complaints, he relished his role. When poet Naomi Shihab Nye, one of his close friends, suggested that he consider spending a few weeks of the summer on a cool beach in California, because he suffered so from the heat, he told her it was out of the question. “I can’t do that,” Maury said. “Being a Maverick in San Antonio is such a minor ego trip, I can’t bear to be anywhere else.”

In the early years of our friendship, Maury was appalled at my ignorance of history. He handed me a reading list that started with the Federalist Papers. The first time I read the Bill of Rights seriously, I asked Maury why it was that people thought the American Civil Liberties Union was just a liberal organization. That’s how naive I was. Maury laughed real hard, but he did not ridicule me. “Come to think of it, I don’t know,” he said. Later, in one of his regular Sunday columns for the San Antonio Express-News, he wrote about the ACLU: “Is it liberal to give some suffering person a blood transfusion? . . . Is a love of constitutional liberty a monopoly of liberals?”

In just this Socratic style, our friendship flourished. When it came to the two great issues of my generation, civil rights and the Vietnam War, Maury was the only person over thirty I knew who was right on both. Although an early backer of President Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam policies, Maury eventually became a vocal opponent of the war. His change of heart came about when he started representing conscientious objectors during the late sixties and early seventies, a period when he never made more than $13,000 a year. Throughout his career, he handled more than three hundred cases pro bono. Many of them became my tutorial in basic civil liberties.

One day Maury took me to lunch with Sporty Harvey, a San Antonio black man who had been a promising heavyweight boxer in the fifties. He had fought white men in Mexico and had wanted to do the same in Texas, but “mixed” boxing was illegal here then. As a legislator in 1953, Maury had introduced a bill to repeal segregated boxing, but it had died before the ink was dry. So Maury filed a lawsuit—I. H. “Sporty” Harvey v. M. B. Morgan—in a state district court in Austin (Morgan was the state official who issued boxing permits). Over lunch, Harvey explained that to him, the issue was more about money than civil rights. He was poor. The purse was larger in a white ring than in a black one. Maury made that an issue in the brief he filed. “This is a case about Sporty Harvey not being able to pick up his grocery money,” he wrote. One of his messages that day was: Never write like a lawyer; use plain English.

The other message was subtler. Leaders of the NAACP were furious with Maury for filing the case at the state level because they knew Harvey stood a better chance in federal court. But Maury wanted to win civil-liberties cases in state court because he wanted to change the mind-set of Texas juries and jurists. He lost the first round but won on appeal at the Third Court of Civil Appeals in Austin. “I wanted to whip ’em in a Texas court,” Maury said. Harvey went on to break the color line in professional boxing in Texas and throughout the South.

To Maury, liberalism was not simply a political philosophy. It was a philosophy of life. He looked at the world as made up of free and equal people who have to figure out how to get along, even if they despise one another. Justice to him was the process by which people learned how to cooperate.

Maury had talked about dying for so many years that somehow I never quite believed he would actually do it. Though he and Julia had no children of their own, Maury collected substitute children by the droves. When word got out that he was dying, many of them—including Lou Linden, one of the early conscientious objectors, and Gerald Goldstein, his legal protégé—made the sad pilgrimage to be by his side.

He hadn’t felt well for months. Although he suspected he had colon cancer, his doctors found a mass in one of his kidneys. After fretting over whether to have an operation, he ultimately decided to have the tumor removed in January, then suffered all kinds of complications.

Before he went into the hospital, he turned in his final column for the Express-News. For more than twenty years his column had appeared on page three of the paper’s Sunday opinion section. Professionally, I don’t think anything in Maury’s life gave him as much satisfaction as writing the column. Naturally, it was controversial. In the eighties his early call for a Palestinian state and his criticism of what he called “the reactionary crowd that now runs Israel” evoked a furious reaction from American Jews. His columns urging the Catholic Church to give up its opposition to birth control angered hard-line Catholics. None of his many editors could ever get him to comply with conventional journalistic practices. For instance, he often interviewed people from beyond the grave—Sam Houston, Eleanor Roosevelt, his father—and ran channeled transcripts in his column. If left to his own devices, Maury probably would have been a newspaperman from the beginning. In time, the column gave him the freedom to think and speak for himself and a healthy degree of separation from his father.

In that last column, which ran the Sunday after he died, he questioned the need for war with Iraq. He knew, of course, that we were going to war and that we would prevail, but he worried that a war would earn us hatred in the Muslim world and lead to more and bloodier wars in the Middle East. “Are we at war yet?” he asked me, near the end. “No, Maury, not yet,” I told him. “Well, thank God for that,” he said. The evening of the day Maury died, President Bush made his case for war in his State of the Union address. I wished it had been in my power that day to tell the world that Bush does not speak for all Texans—that Maury spoke for at least a handful of us.

His funeral went off pretty much as planned. Naomi read J. Frank Dobie’s poem “The Mustangs,” exactly as Maury had ordered. State representative Robert Puente told about the time he’d asked Maury if he had any advice for him. “Yes, I do, young man,” Maury had said, as Puente held his breath, awaiting words of wisdom. “Do your best to keep your seat long enough to get a pension.” This was vintage Maury: funny, unexpected, out of left field.

At the burial, the Jim Cullum Band played “Amazing Grace.” Carolyn Chipman Evans, the founder of the Cibolo Nature Center in Boerne, led the crowd in the hokey pokey. Maury had asked Carolyn to dance the “hootchy-kootchy,” but she had the good sense to demur. As the casket was lowered into the ground, however, a voluptuous woman whose face was covered by a black veil stepped forward and proceeded to do a partial strip over his casket, to the accompaniment of hoots and catcalls from many of the mourners. Apparently, Maury had told one of his neighbors about the hootchy-kootchy request, and the neighbor had arranged for a dancer to do it. I was perturbed and remembered Maury’s constant advice to me about my writing: “Don’t get cute; you’ll be sorry if you do.” In this case, I was sorry Maury hadn’t heeded his own advice.