When the phone rang, Oscar was showing off a letter from an Australian customer who’d bought so many records from his record shop that what he didn’t carry off had to be mailed in staggered shipments overseas. An anxious caller from Dallas was on the line. After a brief exchange, the dignified, snow-haired gentleman calmly yelled across the store, asking employee Sam Shapiro to check on Gary Burton’s Tennessee Firebird, an album long out of print. Without searching, Sam answered in a smug tone born of experience, “We have it.” And he did. On the other end of the line, the caller murmured thanks to Saint Jude.

The record industry sells well over 200 million singles and 200 million albums annually. Since the product looks and sounds the same no matter where it’s purchased, the success or failure of a retailer is usually determined by location and marketing devices like cut-rate prices and T-shirt giveaways. When the supermarket-sized Peaches chain, the largest record franchise in the world, recently expanded into Texas, a glimmer of Hollywood entered the scene: borrowing a gimmick from Grauman’s Chinese Theater, foot- and handprints of rock stars have been immortalized in front of their various outlets.

Oscar Glickman’s Record Shop in Big Spring neither advertises nor offers discounts, and Oscar figures if the Rolling Stones walked into his store he probably wouldn’t recognize them, much less stick their hands in cement. Yet phonograph record devotees from Snyder and Paducah to Sydney, Australia, and Paris, France, know Oscar. He’s the man with the records. Behind the red brick facade and the display case full of faded album covers and World War II memorabilia from his son’s collection, the wooden-floor building is a magical history tour of records. Where else do Lightnin’ Hopkins and Ted Nugent posters coexist? Show me another shop where the Twist section is well stocked and mambos and cha-chas are still categorized.

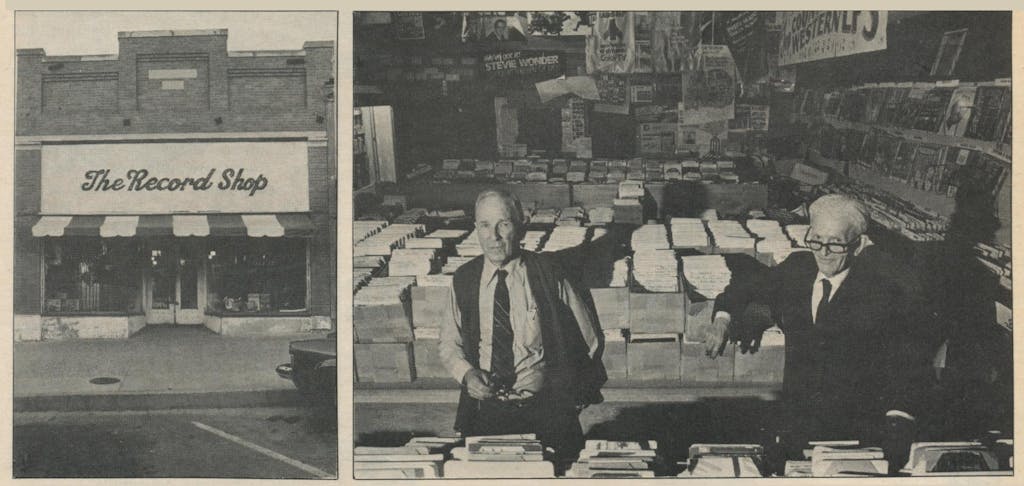

Glickman—that is, Oscar (supposedly he quit doing business with one bank after being addressed one too many times as Mr. Glickman)—has been dealing in records for fifty years, roughly paralleling the development of the plastic platter since its inception. Like Boneau’s in Port Arthur, the Record Rack in Beaumont, and the Radio Center in Fort Worth, Oscar’s place is one of the few remaining mom-and-pop operations left in the state. His wife Bobbie, otherwise known as the Old Lady, recently retired after forty years, although she invariably drops by the store daily. Oscar’s sidekick, Sam Shapiro, always dapper in a pressed suit, starched collar, and with a thick cigar in his hand, has been with him thirty years and has no plans to leave.

Oscar started his career during the twenties in Breckenridge, 95 miles west of Fort Worth, when that area of Texas was in the midst of an oil boom. “We had this little repair place,” the Old Lady said. “It was all messed up with jukeboxes, slot machines, marble machines, and all that.” After accumulating a sizable stock of 78 rpm records from his jukes, he started selling them over the counter. At a time when three companies—Columbia, Victor, and Brunswick—had a virtual monopoly on record manufacturing, Oscar was already in business. By 1948, while Peter Goldmark was perfecting the first long- playing 33(1/3) rpm disc for Columbia, Oscar was a seasoned veteran in Big Spring. He was in the thick of a burgeoning industry and was unafraid to speak his piece. When Columbia wanted to market their new invention solely for classical music, Oscar warned them it would be curtains for their domination of the industry. “I told a representative, we need the race records, the Western records, the records that sell today in 33(1/3), but they wouldn’t pay any attention. Sure enough, that mistake caused not a hundred companies, but maybe five hundred companies to spring up.” Shortly thereafter, RCA spent $20 million perfecting the 45 rpm turntable which would set off a battle between Columbia and RCA in the early fifties known as the “speed war.” At a convention in El Paso where RCA unveiled its new machine to retailers, Oscar committed blasphemy, opining that their player was incomplete until it operated at both speeds. He sent the meeting into an uproar. Even today he prides himself on being a maverick.

Records are usually sold on a 100 per cent consignment basis to retailers who can return all unsold goods to the wholesaler, provided the product is still carried in the catalog. Oscar’s philosophy, on the other hand, was simple: if he bought a record, he kept it. “What broke me from returns was they told me you got to buy the new records, the old ones won’t sell. I figure you just might as well keep what you got and die with it. The Dallas distributors started calling me ‘No Return.’”

The formula made sense the longer he stayed around. Returns were recycled for their vinyl as new products while Oscar’s stiffs gradually became more valuable as they accumulated dust. “It wasn’t that I was smart. The people wouldn’t buy records here. They’d buy them cheaper someplace else. They were left on our hands, that’s all. One of my big faults is overbuying. I’m not too good an executive. Otherwise I wouldn’t have had all these records here.”

The theoretical blunder results in a store with an unrivaled stock. Selling at or near list price rather than discounting, new records are no bargain, but the prices even out over the long haul. Monaural albums listed at $3.98 fifteen years ago are still $3.98. Though Europeans depleted most of the rock-a-billy over the last ten years and most collectors moan Oscar has been picked clean, they inevitably return for another look. Most of the Chuck Berrys, Buddy Hollys, and T-Bone Walkers have indeed vanished. The jazz section was hit hard a few years back after, musicians performing at Schlitz’ jazz fests in Midland caught wind of the place. Despite the wealth of Hank Williams discs, his file has shrunk. But at last check there was still Surfin’ with Bo Diddley, plenty of Astronauts (Everything’s AOK), Pigmeat Markham, Duane Eddy, some Hot Nuts humor. The axiom applies even to records by obscure groups like ? and the Mysterians: sooner or later everything ages enough to become collectible.

Some of the record store’s customers have been celebrities. After Jimmy Reed loaded up on discs, the Old Lady recalled, “He hit three cars backing out when he left here. Another time this boy asked me if we had any Jefferson Airplane records. He asked if I knew who the lead singer in the band was. I said I had no idea. I don’t know who the Beatles are except there’s four of them. He told me he was Marty Balin and I said, ‘Oh yeah?’ He was horrified I didn’t know who he was,” Then there were “those white-haired guys, what’s their names?” the Old Lady asked, searching her memory. Connie Brito, the only clerk under retirement age, pointed to a poster on the wall and cued her: “Edgar and Johnny Winter.” Bobbie continued, “Well, they were on their way to San Antonio to play a show. They’d already picked out a stack of jazz records and they were going through their pockets figuring out how much gas it would take to get to San Antonio. One of them said, ‘If we skip breakfast and eat hamburgers, we can get some more money and eat when we get there.’ Imagine that! Spending every cent except for hamburgers and gas.”

Lefty Frizzell used to drop by to learn the words of his latest record before a show. Lawrence Welk, Bob Wills, George Jones, Jimmie Rodgers, and Ernest Tubb all stopped in to pick, chat, or buy at Oscar’s. One not-so-famous fanatic from the West Coast arrived on a Monday morning at ten o’clock and stayed until Saturday night at closing time without even taking a lunch break. “He told me, ‘I’m not leaving this store until I see every record you got,’” Oscar said.

1974, a rare year of declining record sales according to the Recording Industry Association of America, was Oscar’s best. That was the year he cleaned out his basement. A buyer had picked up the rumor that a pile of 78s in Oscar’s basement was for sale. “I told the guy that I’d sell them to him for ten cents apiece. He asked me how much I had and I said about 22,000. He asked if he could look at them and I told him for ten cents apiece why should he? He called me up I don’t know how many times so I finally told him if he wanted those records to bring $2200 in cash or a cashier’s check. He showed up with a pickup truck and a cashier’s check. I gave him the money back and told him if he was really serious about buying them to go down there and see if he wanted them. He went down there and looked for about an hour and came back and gave me the money.”

Sam said it took three days and a trailer hooked up to the pickup to pack in the records. When the buyer stopped back a few months later, Sam asked him, “What the hell did you do with all those 78 records?” He said, “Sam, you don’t know it but you had the original pressing of Caruso down there. You had forty of those in the basement. We paid a dime a copy and got anywhere from $25 to $40 apiece for them. In six weeks we made $8000.” A lady walked into the store and interrupted the tale. “Are you Sam? I called about an hour ago about a record. . .” Grinning impishly, Sam finished her sentence. “Ah, yes, Jerry Clower, North of the Mississippi. That’s the rarest record ever made.” It had just been issued.

There are rewards in a business that engages in more than mere buying and selling. Like the two record collectors from Abilene and Lubbock who make their monthly pilgrimages to Big Spring. Curious, Oscar once asked them, “What are you kids always spending your money, buying so many records for?” One of them replied, “I’m afraid you might die and someone will take all the records away.” Their fantasyland would shatter. Oscar laughed as if it was an impossible joke. “They’re afraid I might die. They’re actually worried I might die. Of course I’m going to die.”

Waiting in the wings are Oscar’s daughter and son-in-law, ready to keep the store in the family. As it is, Oscar figured, “I’m pretty old now. I’m seventy-five and Sam’s seventy-five. The Old Lady’s retired.” But he can’t get it out of his blood. “I’ll, never retire. I’ll be here until I can’t be.”