On November 27, 1996, William Guess sat in a rented maroon Nissan Maxima surrounded by Harris County sheriff’s deputies, holding a blue steel semiautomatic to his head. Guess was 46 years old, and he was a big man—more than six feet tall, around 240 pounds. He had graying blond hair and a square face. At that moment he was wearing a windbreaker, blue jeans, low-heeled boots, and glasses, bearing little resemblance to the person who had just robbed Guaranty Federal, a small bank north of Houston. About fifteen minutes earlier, however, Guess had been wearing a fake beard and mustache, sunglasses, a baseball hat, and the shirt that had come to be the signature of his alter ego, a serial bank robber known as the Polo Shirt Bandit. Once he had driven away, he had hurriedly pulled off the disguise, and a heady surge of relief probably had flooded through him—he thought he was going to escape once more, back to the part of his life that was ordinary and respectable. On the floor of the car on the passenger side was $12,460. The money had been in Guess’s briefcase when he had walked out of the bank. He could have dumped it out shortly after getting into the car to see how much was there, or it could have tumbled out during the fast turns he had taken in his unsuccessful attempt to shake the deputies who had cornered him. Either way, all those crisp-as-if-starched bills were now spilled out over the carpet: all that easy money, obtained at such immense risk.

Guess had just wrecked the Nissan on FM 1960, a busy four-lane stretch bordered by strip malls, Chinese restaurants, and auto body shops that intersects Interstate 45 and U.S. 290, the Northwest Freeway. The banks that stand along the road’s length are quintessentially modern; they are small outfits, staffed by three or four people, that sit next to day care centers and Hunan Palaces and Repp Big and Tall clothing stores. The branches are as homey and cheerful as a Hallmark greeting card, and you wouldn’t think a robbery would ever happen inside one of them. But to Guess, they must have once looked like a row of cherries, his personal jackpot. This was where he had started robbing banks. Over the span of his career, he is suspected of pulling off at least 38 robberies—making him the most prolific bank robber in the history of the state—and stealing in the vicinity of $600,000. He robbed more banks than Jesse James, John Dillinger, Willie Sutton, or Bonnie and Clyde, although he never hurt anyone. Guess committed one robbery in a town called Salado, two in Austin, and nine within the limits of Houston, but he always came back to FM 1960 or Texas Highway 6 (as the road is known south of 290): Of the 26 additional bank robberies that he is believed to have committed in parts of Harris or Fort Bend counties, 21 occurred somewhere along the road where he now sat. There were never many witnesses around, never that many bank employees to control, and afterward he would slip into the speeding stream of traffic on U.S. 290 or I-45 and vanish.

Not this time. The front of Guess’s Nissan was stuck under the bed of a red pickup truck, and the back of it had been rear-ended by a Harris County Sheriff’s Department patrol car. Two other squad cars had swerved to stop beside the Nissan. What kind of desperation filled Guess, knowing that he was trapped? It would not have been the kind that a crime victim feels—the sudden shock of an entirely unexpected threat. It would have been the sort of dread that steals over a person when he finally confronts a scenario that he has been courting yet running away from for a long time. Four uniformed deputies hurried out of the patrol cars with their guns drawn and took aim at the Polo Shirt Bandit. But Guess had already taken aim at himself.

As detectives learned after they discovered his identity from his driver’s license, William Guess lived in Oenaville, an unincorporated town six miles northeast of Temple, in a redbrick ranch house. He shared it with his wife, Geneva, and the youngest of their three sons. Oenaville is far removed from the urban sprawl of roads like FM 1960; the town consists of a main crossroads, one convenience store, half a dozen ranches, and some houses, surrounded by a vast expanse of rolling prairie. The revelation of the Polo Shirt Bandit’s identity was greeted by the residents of Oenaville with total disbelief. “This is a farming community,” said a neighbor who lives two houses down from the Guess family. “This is the least likely place in the world for something like this to happen.”

William Guess grew up in Temple, where his father worked as the director of the city’s utilities. His family life was unremarkable. He was known to be friendly but reserved—he rarely initiated conversations, although he was happy to stop and talk if you did. “He was quiet, confident, calm, self-assured, intelligent, and a natural athlete,” remembered one friend. As a student at Temple High School, he had achieved nearly perfect grades without having to study hard, and he was an all-around athlete who served as the captain of both the basketball and the golf teams in his senior year (class of 1969). He dated one of the school’s homecoming princesses, Geneva Sanderson. “When I saw him for the first time, it was, like, wow, love at first sight,” Geneva told me over the phone. “We got engaged right after high school.”

“This is a farming community,” said a neighbor. “This is the least likely place in the world for something like this to happen.”

Guess’ single quirk was his apparent lack of drive. Classmates had assumed that because things came to him easily, he would go on to become something of importance, but he didn’t. While friends like Brad Dusek won a football scholarship, left for Texas A&M, and went on to play professionally for the Washington Redskins, Guess attended local colleges but never obtained a degree. As his athletic and academic successes faded, his relationship with Geneva must have taken on an even greater significance. They were married on August 7, 1971. In the mid-seventies, after floundering for a while, Guess found work in Houston as a deliveryman, driving all over the city and its outlying suburbs. On the weekends he would return to Temple, three hours away. Within a few years he gave that up to work as a cleaning-supplies salesman in Temple, and then he started a used-car business with a friend; they called it Two Guys Car Lot. “Many of us felt he was badly underutilized,” said one friend. “He just never seemed to have much ambition.”

After he started Two Guys Car Lot, Guess began spending a lot of time with Cliff Lambert, who worked as a mechanic in an auto shop at a local salvage yard. At the same time, he maintained ties to many Temple residents who were, in the conventional sense, far more successful, such as Brad Dusek and Joel Garrison, who had become homebuilders. He played golf regularly at the Wildflower or Mill Creek country clubs with some of the most prominent people in town, including one of the city’s former mayors, John Sammons. If the disparity between the public images of these people and his own bothered him, he didn’t let on. But he had a big ego, and he liked to prove himself; he played golf to win, and he liked to bet on the outcome. He started off betting $40 or $50 on a round, but in recent years he sometimes wagered ten times that amount.

After friends learned about his secret life as a bank robber, they came to see Guess as an enigma, as if his name proved to be prophetic. They found it impossible to reconcile the character of the man they knew with the activities of the bank robber who wrecked his Nissan on FM 1960. “He was a good friend and a good guy,” said Joel Garrison. “I guess he was just a different person than we all knew.” But in truth Guess’s public life and his hidden one were linked, and the frustrations Guess felt with his daily routine fed the growth of his alternate persona. Those frustrations piled up over time, particularly after he sold his interest in his car business and his marriage began to founder. “There were days, and I mean days, when I wouldn’t hear from him,” said Geneva. “I would stand at the window wondering if he was dead or alive. Then he would show up again thinking everything was hunky-dory.” In 1989 William made an attempt at a permanent break, leaving a note that said, “I can’t go on like this,” but he returned in several days, and the couple decided to stay together for the sake of their children. He was drinking too much—he was twice charged with driving while intoxicated and once checked into an alcohol-abuse treatment clinic. And he started to gamble more.

While people who live in Temple like to think of their city as the last place that would spawn a bank robber, it is a place where a person can easily develop a serious gambling problem, if he has the inclination. The city has always catered to Fort Hood soldiers looking for action, and several used-car businesses in the area (though not Guess’s) have been investigated by the police for serving as fronts for local bookmaking operations. Temple is also home to two weekly high-stakes poker games; the first is strictly private and includes a number of prominent businessmen, while the second is run by local bookies and hard-core gamblers and is more open. Guess played in both. On a routine night, he might win or lose anywhere from $500 to $5,000. If he had been looking for a warning of how far afield the cards might lead him, he had only to look across the poker table: Another regular at one of the games was a man from Temple who had once served time in federal prison. As a young man, he had forced his way into the home of a wealthy widow and held her hostage until she wrote a check for $11,500, which he supposedly needed because of gambling debts.

But if Temple provided the temptation, Guess was willing to be tempted. Besides betting on golf and poker, he started wagering as much as $15,000 on professional football games with two bookies in the Temple area known to their clients (and later to police investigators as well) as Shorty and Champ. Guess started making regular trips to the horse track at Manor Downs, east of Austin, where he would drop as much as $1,500 on a horse, and then he started going to the Isle of Capri casino in Bossier City, Louisiana. He even played the lottery heavily. Nobody seems to have been aware of the extent of his gambling habit. “When I cleaned out his office, I found all these tickets,” said Geneva. “I said, ‘What are these?’” They were from the race track. But people who saw Guess bet could see that he liked to take risks. “William lived on the edge,” said one person who used to bet with him. “He would play blackjack for any amount you wanted. He kept wanting to play for more and more.” So much did Guess come to define himself in terms of his risk taking that when his children were asked what he did for a living, they sometimes replied that he was a professional gambler.

Nobody knows precisely what went through Guess’s mind as he decided to slide into criminal behavior, but the broad outlines of the situation are plain: He was gambling too much, he probably needed money to pay off a debt, perhaps he felt intrigued by images of himself usurping control of something as solid and as reputable as a bank. Did the idea of robbing banks hold some gritty, Western romance for him? Was it his way of getting even with all the people who had grown up to lead ordinary, dull, successful lives? Or maybe he studied the idea with a cold pragmatism, concluding that sticking up banks was a sure way to make easy money.

Several years before he started robbing banks on a regular basis, he apparently committed one isolated robbery in Harris County. That stickup wasn’t linked to others committed by the Polo Shirt Bandit until recently (when a woman who had worked at the bank called the Houston Police Department after seeing Guess on TV and said, “That’s the asshole that robbed me back in 1985”). Four years later, however, Guess started robbing on a systematic basis. On September 29, 1989, he was in Houston—probably to attend an automobile auction—and had checked into a Holiday Inn on 290 where he often stayed. It’s likely that he went somewhere else to change clothes. The branch of San Jacinto Savings that he had decided to raid was in a strip mall on Texas Highway 6, next to a Montessori Children’s Cottage, a Kids Kuts barbershop, and Copperfield Family Dental Care. It was a small bank, only women worked there, and Guess knew he could keep an eye on all of the employees at once. When he walked into the place at around noon, Guess looked like any nine-to-five businessman: He was wearing a dress shirt, a light blue vest, a tie, dress slacks, a driving cap, and dark sunglasses. He had painstakingly applied a realistic-looking false beard and mustache (a crepe beard, as the disguise is known, involves brushing spirit gum on the face, then attaching fake facial hair clump by clump), and he was carrying a large zippered daily-planner case, but the only thing inside was a small blue revolver, probably a .38. Guess took out the gun and told the tellers to dump the cash from their tills into the daily planner. From behind his pitch-dark sunglass lenses, he might not have been able to make out the tellers’ features, but he must have sensed the fear and vulnerability that he aroused. One minute the employees had been in charge of the bank, and the next minute he was. After warning the tellers that he had an accomplice outside who was also armed, which wasn’t true, Guess drove away in a brown Mercedes that he had probably bought at the auction.

Guess lifted a total of $1,000 from San Jacinto—not that much money. None of his early robberies was particularly lucrative; he knew tellers usually trigger a silent alarm, and he had only minutes before the police would arrive. Typically he got away with between $4,000 and $15,000. Only much later did he get larger hauls. But he must have found that first job rewarding enough, because it wasn’t long before he struck again. One month after robbing San Jacinto Savings, he held up tellers at an NCNB (as NationsBank used to be known) on Highway 6, in Fort Bend County. Two weeks later, he returned to Harris County to rob First Federal Savings and Loan on FM 1960. Witnesses saw him flee in another Mercedes, this time dark blue, license plate number 437 HFT. In December he hit the same NCNB again, and in January 1990 he returned to rob the branch for the third time. Then there was a lull.

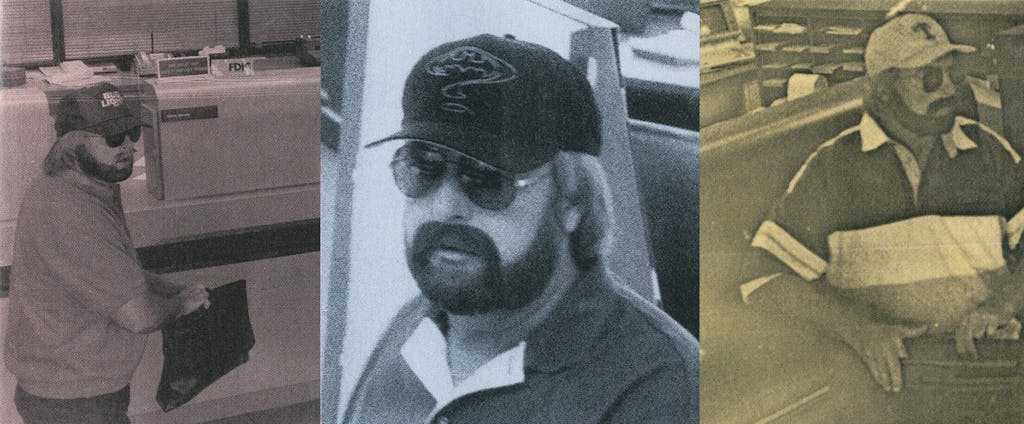

Somebody had just pulled off five bank robberies in less than four months, which was galling to the detectives assigned to solve the cases. Among the law enforcement agents who converged on San Jacinto Savings after the first robbery in 1989 were Lieutenant Grace Hefner, who was in charge of the Harris County Sheriff’s Department robbery division, and Detective Tom Keen, who reported to her. Hefner is a reserved, soft-spoken, tenacious woman who is known for her ability to crack tough cases by carefully cataloguing large amounts of data. Keen, by contrast, is a gung ho, right-off-the-streets detective. Keen and Hefner would spend the next seven years trying to solve the San Jacinto robbery, but at the time it looked like a run-of-the-mill crime, and there was no reason to suspect that the investigation would prove inordinately long. Later they came to realize that the robbery was unusual in one respect: “That was the first time we saw such an elaborate disguise,” said Hefner recently. “Usually they just wear a hat and sunglasses. We don’t usually see fake beards.” But back then, nobody knew that the bank robber’s beard was false. They did notice the luxury automobile that he had driven off in, which was how Guess acquired his first nickname—originally the police referred to him as the Mercedes Bandit.

“This man was just fortunate. He had lots of breaks.”

Most bank robberies are solved within a matter of weeks, but the robberies attributed to the Mercedes Bandit continued to mount, while Keen and Hefner made no progress. At least in his secret life, Guess must have felt charmed. Once he was almost caught when a police officer arrived in the middle of a robbery, but the officer mistakenly accosted another bearded man as Guess drove away from the scene. Another time Guess robbed a bank while an armed security guard was in the back of the institution fixing a cup of coffee. “This man was just fortunate,” said Keen. “He had lots of breaks.”

Guess was also smart; when Keen checked his computer system, the license plate number that the tellers at First Federal had written down popped up as belonging on a Hyundai. The owner of that car had reported its plates stolen from the parking lot of a medical office building on FM 1960. Guess was taking off the stolen plates and removing his false beard as soon as possible after each robbery (he had abandoned the crepe beard in favor of a prefabricated one that he could rip off all at once) to confuse any law enforcement officers he encountered. He also coated his fingertips so that they left no prints. About the only clue Keen and Hefner had to the bank robber’s identity was his peculiar ability to get his hands on different cars, none of which were being reported stolen; this seemed to indicate that he was in the used-car business. The detectives also believed the bank robber had to be from Houston, because he knew his way around. In the spring of 1990 the theory that the Mercedes Bandit was a local car dealer led the sheriff’s office to charge an innocent man with some of the robberies that Guess is now suspected of having committed. Frustrated by the lack of progress, the sheriff’s office distributed a surveillance photograph of the Mercedes Bandit to television stations and newspapers in the Houston area. Somebody called in and said the person looked a lot like Aubry Lee Kelley, who was in the vehicle-repossession business. Several witnesses picked him out of a lineup. Although Kelley immediately protested that he was innocent, he spent the next two months in jail—until Guess returned to San Jacinto Savings, the first bank he had held up and one of the two that Kelley was charged with robbing. This time he fled in a black Mazda, but the tellers were certain he was the same man who had robbed them before. The charges against the unfortunate Kelley were dropped. “Nobody listens to you in that jail,” Kelley told the Houston Chronicle shortly after his release. “They don’t care if you’re guilty or innocent. They’re just pushing people through court.” If he sounded bitter, he had good cause; while Kelley was in jail, he lost his repo business, was kicked out of his apartment in the Woodlands, and his wife suffered a miscarriage.

Soon after Guess resurfaced, inadvertently springing Kelley from jail, he decided to move into new territory and alter his disguise, as if he felt he had to vary his routine to keep ahead of the police. On May 21 he ventured into Houston and hit Mason Road Bank (now called Comerica), a small adobe-style building much like the institutions he had been robbing up and down FM 1960. On July 3 he robbed the same bank again. Despite its name, the bank lies on Blalock Road, which runs directly into I-10, and after both robberies Guess simply disappeared into traffic. By now he had abandoned his Mercedes for cars that were less noticeable. In the second robbery of Mason Road Bank he also abandoned the Mercedes Bandit’s business attire for a more casual look: He was still using a fake beard and mustache and sunglasses, but now he wore a white polo shirt with blue stripes, blue jeans, low-heeled boots, and a baseball hat. From that point on, he wore a polo shirt in every robbery he committed.

Why Guess reconfigured himself as the Polo Shirt Bandit remains an unanswered question; maybe he adopted the look to make the police think they were dealing with a different bank robber. Whatever the reason, the new disguise was an improvement: While the Mercedes Bandit had posed as a typical businessman, the Polo Shirt Bandit was even more ordinary, and therefore more invisible. The new apparel seemed to transform Guess into a generic Bubba, a Texan Everyman, just another big guy in a gimme cap.

The two Houston robberies brought Guess’s heists to eight and the number of law enforcement agencies hunting for him to five, as the Houston Police Department joined the Harris County Sheriff’s Department, the Fort Bend Sheriff’s Department, the Sugar Land Police Department, and the FBI. Guess must have spent some time conjecturing about his pursuers, but he must have felt secure enough once he made it back to Oenaville; the town was surely too tiny, too rustic, and too remote to be the scene of his unmasking. And if his occasional trips to Houston began to acquire an element of serious risk, well, Guess had long had an appetite for risk. Before he had chanced his livelihood; now he was gambling with his freedom.

During his next jobs, Guess displayed an unusual ability to think fast under pressure. On September 18, 1990, he visited a branch of Guaranty Federal Savings that sits in a shopping center on Jones Road, near FM 1960. He was wearing his disguise, and he issued the same set of instructions, but before he left the bank, a dye pack that he had scooped into his briefcase along with the money exploded, shooting a fine red powder that looked like smoke into the air, staining his skin and clothing, and spraying a chemical agent that made his eyes burn and water. If he had taken the time to look for clean money, Guess might have been caught, but he immediately threw the briefcase down and ran off, leaving the cash behind. Apparently he had a pressing debt to pay, however, because only three weeks after the dye pack went off, Guess returned to rob a bank called Commerce Savings. The following year, he robbed Guaranty Federal for the second time. “Okay, girls,” he said to the tellers with characteristic aplomb. “Let’s do it right this time: No dye packs.”

Several months later, the same audacity helped Guess brazen his way through the most harrowing moment of his criminal career. In the summer of 1991, perhaps because he was concerned about hitting too many banks near Houston or the target was too tempting, Guess decided to rob a branch of Taylor Banc in Austin. The one-story, redbrick building stands on the crest of a hill at the intersection of Braker Lane and I-35. It is clearly visible from the highway, and Guess probably spotted it on a trip to Manor Downs. As soon as he saw the building, he must have imagined how easily he could rob it: The bank was just the right size, and a getaway looked simple—although as it turned out, it wasn’t.

Whatever qualms he may have felt were no match for the pull of his addictions.

At eleven-fifteen in the morning on July 18 Guess drove up to Taylor Banc in a two-tone Chevy pickup. He walked into the lobby wearing a fake beard and a polo shirt and carrying a Titan chrome .32-caliber semiautomatic in his briefcase. The robbery went off without a hitch, but the Austin police responded within minutes, and when Guess tried to disappear into the northbound traffic on I-35, he kept running into patrol cars. A police helicopter soon appeared overhead. Spooked, Guess finally drove down a dead-end street and got rid of every piece of evidence that could tie him to the crime. He shucked off his shirt, jeans, belt, boots, hat, and beard—everything he had worn into the bank—shoved them into a plastic trash bag and heaved it out the window of the truck. He also dumped the money, the stolen plates on the truck, and the Titan semiautomatic. “He got naked,” said one detective. Then he pulled on different clothing and drove away. The police didn’t have a vehicle description, and they were looking for a bearded man in a baseball cap and a polo shirt; if any officers encountered Guess, they didn’t recognize him as their suspect. Shortly after Guess left, a patrol car turned onto the street. A woman who had seen Guess change his clothes pointed out the pile of belongings in the trash bag, but by then Guess was gone.

On that occasion the debts that Guess had amassed must have been particularly onerous. One day after leaving Austin empty-handed he showed up in Harris County and robbed a Bank of America, and the day after that, as if he still hadn’t gotten the amount he required, he robbed a branch of San Jacinto Savings. Before the end of 1991, he robbed four more banks, all in Harris County, boosting the number he had hit to nineteen.

Keen, Hefner, and the other detectives looking for the Polo Shirt Bandit obtained the first and only items of physical evidence they ever got during their investigation from the pile of stuff Guess left in Austin. From the fake beard, they learned that their suspect had been using a disguise. The investigators had already decided that the bank robber probably had a steady source of income, since his robberies took place in an irregular sequence; considering his actions after the botched Austin robbery, Keen and Hefner felt certain that their suspect had a gambling problem. “Who else would be going through that kind of money other than somebody with a drug problem?” asked Keen. “And he didn’t look like somebody who was into drugs. He stayed the same weight.”

But the evidence and the suppositions led nowhere. Keen and Hefner contacted casino officials around the country, but their quest turned up no useful tips; partial fingerprints recovered from the license plate Guess left behind in Austin didn’t match any on file. The Harris County Sheriff’s Department turned to the media for new leads. On December 17, 1991, the Houston Chronicle published a surveillance photograph obtained the week before, and after the picture ran, the sheriff’s office got a tip that the bandit resembled another man who owned a car-repossession business. The suspect’s partner also looked like the Polo Shirt Bandit, however, and detectives decided the two had been taking turns at wearing the same disguise. Early in 1992 the sheriff’s office arrested both men and charged them with some of the Polo Shirt Bandit’s robberies. “In each case they would wear sunglasses, a baseball hat, and a beard,” someone from the sheriff’s department told reporters at the time. “If you look at the surveillance photos, it’s hard to tell the difference.”

Both men were released, but they soon would have been cleared anyway: On February 19, 1992, the Polo Shirt Bandit returned to Harris County to rob a branch of Cypress National Bank on Jones Road that he had robbed once before. “This is the last time I’m going to rob a bank,” Guess told the tellers at Cypress National. “I need this money for my son.” And then the robberies stopped, as abruptly as they had begun.

William Guess did not have a sick son. Detectives now believe he was just trying to justify his actions to the people he was holding up. However, it is possible that the strain of leading a double life had begun to affect him; Geneva recalls that William had constant stomach problems and was always eating Tums. (Three years later Guess would suffer a heart attack.) If he was ever to interrupt the cycle of compulsive gambling and criminal activity he had fallen into, this would have been the occasion. However, whatever qualms he may have felt were no match for the pull of his addictions: On February 23, 1993, a year after saying he was through with crime, Guess packed up his gun, his fake beard, one of his polo shirts, and resumed his bank-robbing spree. He stole the license plates off a car that belonged to an employee of a fast-food restaurant on U.S. 290 and put them onto the white Ford Thunderbird he was driving. Like many of the cars he used from then on, it looked new; apparently Guess started using rental cars instead of used ones. Guess then headed for the Bank of America on FM 1960 and held it up for the second time.

Three months later Guess committed a robbery that was the one most likely to have led to his capture—it was like a beacon announcing his approximate home base, although none of the detectives searching for him understood this at the time. On May 20, 1993, Guess held up Peoples National Bank in the scenic town of Salado. It was the only robbery that he ever committed in Bell County, where Oenaville is located—Salado is only about twenty miles from Guess’s home. While his success in evading capture thus far was largely because he had avoided robbing banks in places where he might be recognized, Guess must have found Peoples National irresistible: The old stone building sits so close to I-35 that the highway entrance ramp is visible from the bank’s parking lot, and Salado has no police department of its own. Law enforcement agents had to come from Belton, ten minutes away. Breaking from the routine he had used in the past, Guess stayed inside the bank long enough to force the employees to open its vault, and while the police have never disclosed how much money he got, it was far more than his usual plunder.

One week later the Temple Daily Telegram linked the Salado robbery to “a professional bandit” who was described as being from around Houston. The article outlined the Polo Shirt Bandit’s methods and appearance, and it included a photograph of Guess in disguise. “Authorities do not believe the robber remained in the Central Texas area,” reported the paper. “However, anyone able to confirm the true identity of the man pictured in the photograph is urged to call the sheriff’s department.” Half of Temple must have read the story—Guess probably saw it himself. In the meantime, FBI agents showed photographs of the Polo Shirt Bandit at work in other banks to Jerry Kopriva, who was in charge of security for Peoples National in the area at that time. Kopriva had known Guess in high school, and they had become reacquainted when their children started attending the same schools. Kopriva studied the photographs and never realized he was looking at William Guess. “I had no earthly idea,” he said recently.

While the life went out of William Guess, who was sitting in a junkyard for hours at a time, the Polo Shirt Bandit grew more potent; it was as if one waxed and the other waned.

In retrospect it seems weird that a beard, a gimme cap, and a pair of sunglasses were enough to render Guess unrecognizable, but apparently people who knew him were incapable of seeing through his disguise because the idea that he might be a bank robber was unthinkable. And Guess never revealed any sign of his illicit career to his friends or neighbors; he never changed his lifestyle in any obvious fashion, and he was never suddenly and inexplicably rich. “He never flashed a hundred dollar bill,” said a neighbor in Oenaville. “He’s lived here for ten years, and he’s always driven around in an old vehicle.” Geneva and William had separate bank accounts, and his family was never aware of any change in William’s finances. “He was a penny- pincher,” said Geneva. “It was a big joke with the kids: ‘Daddy’s cheap, cheap, cheap.’ When we went on vacations, he would want to stay in some dumpy old motel. He was happy buying clothes at Wal-Mart.” He never boasted of his illegal exploits, not even when he was drunk.

Perhaps he never slipped because nobody knew him that well anymore. After selling the car business, Guess had drifted into buying old cars at auctions, fixing them up, and selling them to other car dealers, and he was spending almost all his time at the garage owned by Cliff Lambert. The property sits on a bluff, and it is strewn with every model of vehicle imaginable, including two-doors, four-doors, old pickups, a few Winnebagos, and even an old powerboat. When friends asked if he was going to get back into the used-car business on a more formal basis, Guess replied no, not unless he had to. “Gradually he built a shell around himself,” said an old friend. “In the last five or six years, it was like he had a chip on his shoulder. He was more aloof.”

As if Guess was alarmed by the publicity the Salado bank robbery attracted, he committed no more robberies that year. He started up again in 1994, however, and from that point on he became more and more effective as a criminal. Guess had been learning on the job, and in the last phase of his career, he figured out how to avoid security measures like dye packs and how to coerce employees into letting him into the vaults. While the life went out of William Guess, who was sitting in a junkyard for hours at a time, the Polo Shirt Bandit grew more potent; it was as if one waxed and the other waned.

Early in 1994 Robert Davenport, a detective newly assigned to the Houston Police Department’s robbery division, was handed material on the serial bank robber. The police department’s interest in the Polo Shirt Bandit had been reignited on January 4, when the bank robber hit his third institution within the city limits. A subsequent Houston robbery—at Pinemont Bank, on Memorial, on May 19, 1994—provided Davenport with what he thought was a big break. “We got an excellent video,” he said. “It showed his every movement. It showed him pointing, holding his weapon, walking. There was a strong front-on facial shot, a good profile, even a shot of the back of his head. It was perfect.” The videotape of the Polo Shirt Bandit robbing Pinemont first ran on the TV show City Under Siege, then appeared on local news, and eventually aired again on America’s Most Wanted. Davenport researched every name that turned up and found many people who bore a striking resemblance to the Polo Shirt Bandit, but nobody who had committed his crimes. “One woman was so upset she went into convulsions because she thought it was her ex-husband,” he remembered. Investigators began to feel certain that the bank robber didn’t live in the Houston area, since the publicity would have unearthed him if he did. Davenport distributed wanted posters at police roll calls around the city and held seminars for bank employees to teach them about the bandit’s habits. He worked until he had the sense that he knew the Polo Shirt Bandit, even though he didn’t know his name, and still the bank robber wasn’t caught. He robbed eight more banks in the next year and a half. Then he started using a semiautomatic that carried more firepower than any he had used before.

On April 11, 1996, Guess showed up at a Compass Bank on Bissonnet in Houston. The wedge-shaped bank building looked small from the outside, but once Guess was inside, he discovered that it was much bigger; Guess was forced to spend far longer in the bank than he wanted to, as he had to round up employees from various offices before he could get his money, and he grew visibly jittery in the process. During his next robberies, his manner became increasingly ominous. Guess started getting more aggressive, more nervous, and more demanding; he began pointing the gun directly at bank employees, whereas before he had only displayed a weapon to show them that he was armed. How had the years of assuming the role of the Polo Shirt Bandit changed William Guess? What actions was he now capable of? On July 24 Guess got into the vault of a Savings of America on Post Oak and walked off with $31,823—a vast difference from the $1,000 he had taken from San Jacinto Savings almost seven years before.

As Guess’s behavior became more threatening, law enforcement officers began to put more and more effort into his capture. The Harris County Sheriff’s Department formed a task force to catch the man that everyone in the robbery division had come to think of as their nemesis and put Grace Hefner in charge. In the middle of 1995 a bank association had offered a $10,000 reward for information leading to the capture of the Polo Shirt Bandit. By last summer, when Guess showed up with a bigger gun, the reward being offered was up to $26,000. Davenport said, “We didn’t know whether he was making a statement: ‘I’ve got more bullets. I’m ready for a shoot-out.’”

And then Hefner noticed a pattern. Beginning in February 1996, as if he had been lulled into complacency or was getting sloppy, Guess had started robbing a bank every 50 to 56 days. He had robbed on February 15, April 11, May 31, and July 24. By September 11, the Harris County Sheriff’s Department, the FBI, the Houston Police Department (HPD), and the Texas Rangers convened to figure out how to respond. One week later Guess cleaned out the vault at a branch of Coastal Banc, scoring more than $60,000, and that caused law enforcement agencies to disagree about what he was going to do next: The FBI and the HPD argued that the robber had just gotten so much money that he wouldn’t rob again for some time, while Hefner thought his gambling had become so compulsive that he would strike again within the 56-day time frame. The sheriff’s department and the Texas Rangers decided to set up a surveillance operation over a three-week period in November, when they thought the Polo Shirt Bandit was going to hit, but the FBI and the HPD decided not to participate.

But then, as if a fickle wind turned the weather vane of his fortune around, everything started to go wrong.

After juggling schedules and rearranging long-planned vacations, a team of eighty uniformed and non-uniformed officers was assembled. Hefner briefed them about the bandit’s habits. She also told them to anticipate that the bank robber would try to kill himself or shoot his way out of a corner if faced with the prospect of arrest—the Polo Shirt Bandit was relatively young and had committed dozens of serious crimes, meaning that he was facing an extremely long prison term. Beginning on November 5, the officers sat in parked cars outside of banks that looked like the kind of places that the Polo Shirt Bandit liked to stick up, and waited. He never showed.

By November 25 the three weeks were up, and the sheriff’s department was about to call off the surveillance. Then bank executives requested that the extra protection remain in place through the Thanksgiving holidays. The sheriff’s office decided that it couldn’t afford to keep all 80 officers on the lookout for a bank robber who might not show up, but it did keep about 25 officers on the alert.

On Sunday, November 24, William Guess got a phone call from a friend in the car salvage business in Houston. The friend told Guess that there was going to be a big automobile auction on the following day. On Monday, Guess drove to Houston, checked into the Holiday Inn he often stayed in, and went to the car auction. On Wednesday morning, he put on his bank-robbing attire and drove a rented Nissan over to Guaranty Federal, at 3902 FM 1960. Apparently he sat in the car for some time (police officers later found a cooler and a lot of empty beer cans in the car). At ten-thirteen Guess went into the bank, where he displayed his gun and ordered the tellers to fill his briefcase with cash. But then, as if a fickle wind turned the weather vane of his fortune around, everything started to go wrong.

A woman who worked at another branch of Guaranty Federal had stopped by the location on FM 1960 that morning, and as she was leaving, she noticed Guess enter the bank. As it happened, the woman had attended one of Davenport’s briefings, and she recognized Guess as the Polo Shirt Bandit. Recalling what Davenport had said to do during such a situation—“If you ever see this man, call 911”—she dialed the emergency number on her cellular phone. The dispatcher kept her on the phone until Guess emerged, and the woman was able to report that he left the bank in a maroon Nissan Maxima, license plate STS 05X, heading west on FM 1960.

Ron Fleming and Mitch Hatcher, who were normally assigned to a narcotics unit, were among the only Harris County deputies still out looking for the Polo Shirt Bandit that morning. After patrolling up and down Jones Road for a while, Fleming, who was driving, had said, “There’s nothing going on here, let’s cruise over to 1960.” Right after they turned onto FM 1960, the dispatcher announced that the Polo Shirt Bandit had struck again and gave them a vehicle description and location. “He was heading right to us,” Fleming recalled afterward. As the dispatcher was repeating the bank robber’s vehicle and license plate number, Hatcher and Flem-ing spotted the maroon Nissan in oncoming traffic. Thirty seconds later, and they would have missed him. Fleming made a U-turn. “We got him! This is him!” he started yelling to his partner.

When the patrol car pulled up behind him, Guess waved as if to show that he would pull over momentarily. His mind must have raced to consider whether he had committed a traffic violation or whether this was the confrontation that some part of himself must always have been anticipating. The patrol car moved up behind him, close enough for him to study the faces of the two deputies in his rearview mirror. Apparently something told him that they knew exactly who he was. As soon as he saw a break in traffic, Guess took off, running a red light. The patrol car turned on its siren and followed. Guess led Hatcher and Fleming on a chase through a Builders Square parking lot, several other red lights, and up and down streets that intersected with FM 1960. Two other Harris County Sheriff’s Department patrol cars joined the caravan along the way. Guess kept leaving the main thoroughfare in a vain attempt to shake the cars on his tail, but he always came back to his primary getaway route.

About ten minutes after the chase began, Guess and the three patrol cars came tearing down FM 1960 toward the intersection at Perry Road. Sitting in a red pickup in the far left lane was Steve Sharum, a Deer Park plumber. Sharum had been just a few cars ahead of Guess when Hatcher and Fleming had first spotted the Nissan, and he had watched as the patrol car turned around, and the maroon car had zipped out to run the red light. Sharum’s younger brother had been killed in a car accident, and the reckless driving of the man in the Nissan had ticked him off. “That guy’s driving ignorant,” Sharum had thought. “He must have stolen that car.” Now when Sharum looked up and saw the same Nissan Maxima in his rearview mirror, bearing down fast, he thought, “Well, if I stop, he’ll either have to stop too or go around me.” Sharum closed his eyes, held on to his steering wheel, and punched the brakes. He felt two jolts—Guess smashing into his pickup, and the third patrol car slamming into Guess. Then Sharum heard someone yell, “He’s got a gun!” so he lay down on the front seat of his truck and didn’t move.

Once he rear-ended Sharum’s pickup, Guess knew his long charade was finished. He had planned what he would do in such a moment. Perhaps he knew the moment was inevitable, because he robbed banks like he gambled—he didn’t stop until he was completely out of luck. Guess put the blue steel semiautomatic to his temple. When the deputies jumped out of their cars and surrounded him, he fluttered his other hand at them, as if he could shoo them away. “It’s over,” he said. “I haven’t hurt anybody. I don’t want to hurt you. It’s over.” Guess let the gun slip down a little bit, then lifted it back up and fired. His head slumped forward on his chest.

Tom Keen was the first detective to arrive at the crime scene. He took one look and knew that he wasn’t going to learn much about the hidden life of the man in the car. All the essential facts were bleeding out of him. “Fellah, I’ve been looking for you for a long time,” Keen said to the slumped-over man. “Now I finally get to see you, and look how it’s ending.” Robert Davenport had learned that a chase was in progress from an HPD dispatcher; once it ended, he started to head over there, but he changed destinations once he learned that Guess was being flown to Hermann Hospital. Davenport was waiting at the emergency entrance when Guess arrived. “I was hoping that I could look at him and just know, but a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head is a pretty ugly thing,” said Davenport. While doctors hurried to stabilize Guess’s condition, Davenport snapped photographs of his immobile figure. The hospital staff also allowed the police to take fingerprints of the still-unconscious man. Davenport immediately contacted the police department’s lab and had them compare Guess’s prints with those left by the Polo Shirt Bandit in Austin. “Lo and behold,” said Davenport. “Bing. They were his.”

Geneva was at home preparing for Thanksgiving when she learned from a reporter that her husband was the Polo Shirt Bandit. She never went to Houston to visit him. “I didn’t want to,” she said. “I was just so angry that he could do such a thing. What really upset me was the statement he made to the police about how he had never hurt anyone. I thought, ‘Well, who are we?’”

William Guess died without regaining consciousness on January 4. Since his secret life was unmasked, Geneva has discovered bills for credit cards that she didn’t even know he had. William had been taking out large cash advances on the cards and Geneva has been left with the bills. “I just cannot figure out what happened to the money,” she said. “There is no money. His savings account, everything, it’s all wiped out. I think he left me with $184.”

To his surprise, Davenport felt none of the elation he had expected to feel, no sense of satisfaction, at the conclusion of his investigation. Even though Guess had been found, it was as though he had eluded capture after all. “I was just so disappointed,” the detective said. “I was mad, I guess, mad at him, more than anything. I was crushed to see him and know that he would never answer the biggest questions I had. I knew the what, where, when, and how. But why? What made this man turn to a life of crime?”