This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue with the headline “Once Upon a Time in South Texas.”

In this exclusive excerpt from James P. McCollom’s The Last Sheriff in Texas, one of the state’s deadliest lawmen is gunned down in a 1947 shoot-out that captivated the country and left many locals to wonder whether or not he had it coming.

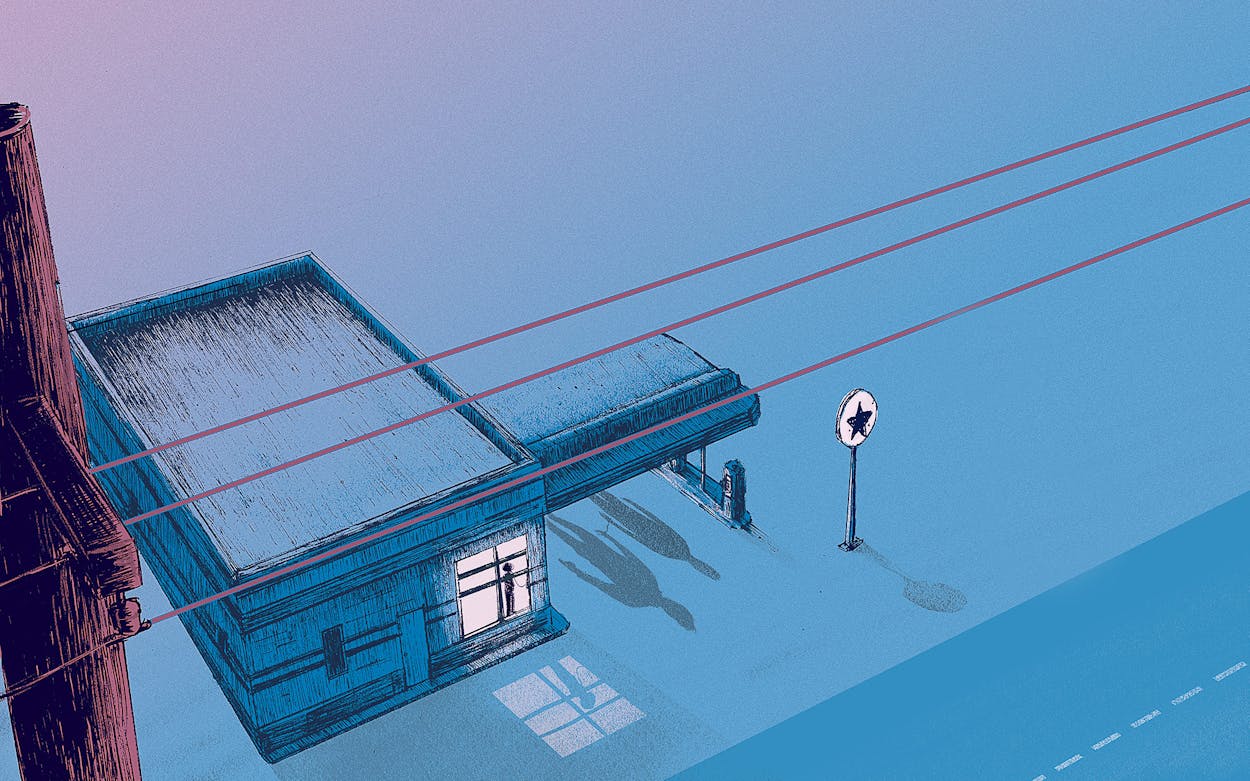

The man who shot the sheriff was Pat Hines. A 34-year-old ex-con, Hines was a grifter on his way from Oklahoma to Mexico. He and his accomplice, William Raymond Pittman, who was also 34, had hitched a ride south with a traveling preacher and his family in their Mercury station wagon. On November 10, 1947, they stopped to refuel at the Magnolia filling station, in Pettus, halfway between San Antonio and Corpus Christi.

When Houston Pruett, the hefty station manager, came out to service the car, he noticed that three men sat crowded in the front seat, and a woman and two small children were in the back. Pruett pumped two dollars’ worth of gas and then popped the hood to check the oil. When he looked up, he saw the Bee County sheriff, Robert Vail Ennis, coming around the highway curve in his metallic-green Hudson.

The sheriff’s Hudson was a familiar sight for residents all across the county. For those who saw him as a white knight, the sight was thrilling. For others—quite a few others—his appearance stirred fear. Pruett himself considered Vail a friend. Vail often stopped by the Magnolia station to grab a Coke and ask after one person or another. But after wheeling into the station, Vail didn’t greet Pruett. He went straight to the passenger side of the station wagon. “Did you fellers catch a ride with this man?” Pruett heard the sheriff ask.

Pittman, who was sitting by the window, said yes. “Get out, you’re under arrest,” Vail told him. The sheriff frisked him (“He searched him real good,” Pruett recalled during an interview in 1977. “Head to feet.”) and then turned to Hines, who hadn’t moved. “I told you to get out, you’re under arrest.”

Hines, a big man, did as he was told. Vail handcuffed them together and then told Pruett to call Harper Morris, the sheriff of nearby Karnes County. “Tell him I’ve got the two men he wanted,” Vail said. (Pruett, who was watching carefully as Vail put on the handcuffs, would later recall: “[Vail] handcuffed the little one, and the big one reached him his right arm. Didn’t notice that then until after the shooting. He was left-handed.”)

Inside the station, Pruett picked up the telephone and waited for the operator’s voice. Vail halted Hines and Pittman just inside the door. Pruett would later say that Vail “turned around to ’em and said, ‘You boys wait right there, that’s far enough.’ Just as nice as he could be.” Then, as Vail turned to take the phone from Pruett, Hines reached down with his free hand—his left hand—and pulled out a Smith & Wesson .38. “Drop that receiver,” he demanded.

“Wait a minute,” Vail said, reaching for his own Colt revolver. Hines, standing four feet away, started shooting.

Fifty years later, people could tell you exactly where they were on the day Vail Ennis was shot five times. Wayne Dirks, twelve at the time, was hitching a ride to Tuleta, three miles south, after junior high football practice. He and a friend saw the commotion at the Magnolia and jogged down to see what had happened. “When we got closer, we could see all this blood on the highway, probably a twenty by twenty area, solid blood,” Dirks remembered. “We walked right up to it. The bodies were still there. Someone had covered them up. There was blood everywhere. There must have been a pool of blood twenty feet across. I can see to this day one of the workers at the station taking a hose and trying to wash it away.”

The Beeville Bee-Picayune noted that a canvas covered everything but a single arm, which bore a tattoo of a severed heart. But there were, in fact, two bodies beneath the canvas. And neither of them was Vail Ennis.

Jack Robinson, later a sheriff himself, was one of the first in Beeville, the county seat and Vail’s hometown, to find out about the shoot-out. Driving down St. Mary’s Street after work, he saw the sheriff’s Hudson parked in front of the Beeville hospital, the doors open, nobody in it, the police light still flashing. “I just figured Vail had shot somebody again,” he said.

Inside the hospital, a young ranch hand (and the author’s older brother) named Cread McCollom Jr. lay on a table in the emergency treatment area, a bandana wrapped around his left hand, waiting for the doctor. He had worked cattle on the ranch in Cadiz that day and ripped a two-inch gash in his thumb. Coal oil and camphor, his grandfather’s usual treatment, hadn’t fixed it. Suddenly, the door opened, and there was Vail, his white shirt soaked in blood. The doctor, James Edmondson, came in and said, “We need that table, Cread. Just lie down on the floor.”

Outside, a small crowd of lawmen and onlookers had formed in the hospital yard. L. D. Hunter and Reese Wade, the sheriff’s hunting partners, were there. Some high school boys came by; they drove to tell others. By nightfall, the yard was crowded. The weather was overcast and raw. The county had seen the first frost of the fall over the weekend, temperatures were in the middle thirties, and it had rained almost an inch early that morning, a Monday. A single streetlight at the corner of St. Mary’s and Jones did little to light the funereal scene.

Inside the hospital, Vail Ennis lay dying at the age of 43. No one said it out loud, but they all knew that Vail’s life was meant to end this way. Vail had long been controversial, and he had now killed the sixth and seventh man of his career, making him one of the deadliest lawmen of his era. That gloomy night became the moral high point of his time as sheriff of Bee County. His death would gray the memory of his own killings. His many enemies would be obliged to show compassion for his widow and small daughter—obliged to join the mourners at his funeral.

Assuming, of course, that he would die.

The American Cafe that week saw a gathering of old-style sheriffs. They drove in from the neighboring cattle counties to join the vigil. Each was the unquestioned law of his county. Texas, proud of its size, was a small world. Here in the brush country, the pioneers had laid out their towns thirty miles apart—the distance a covered wagon could travel in one day. From Beeville, it was 30 miles northeast to Goliad, 37 miles north to Karnes City, 30 miles south to Sinton, 32 miles southeast to Refugio, and just under 30 miles west to George West. Distances in frontier Texas were vast but undaunting. A single man on horseback could easily cover 50 miles in daylight.

Standing next to one another, the sheriffs of Karnes and Live Oak counties made a spectacle. Harper Morris was five feet tall; he wore a size 4 boot. Albert Smith was a huge, lumbering, rock-hard man. He had been sheriff of Live Oak County for two decades, and he was almost as feared as Vail. Grifters steered clear of Live Oak just as they steered clear of Bee. Harper Morris, meanwhile, had a legacy that pretty much guaranteed him a lifetime as the law in Karnes County. His father, W. T. “Brack” Morris, was the sheriff shot and killed by the legendary Gregorio Cortez, in 1901.

Vail Ennis wasn’t dead yet, but he was close enough for these hard realists to tell stories and laugh aloud about them. Most stories were about guns. No one questioned Vail’s skill with a sidearm, but his friends ribbed him about hunting. Around here, bird season—dove and quail—was more important than deer season, and there was much to argue about. Who was the better shot? Who had the better dogs? Vail had bragged about his dogs and bragged about his car. He said his Hudson was the heaviest, fastest car in Texas.

At every table, there was expert speculation about what had happened at the Magnolia station. These men knew about the damage guns could do. Was it believable that the sheriff had been shot five times in the belly before he fired back? Who could survive .38 slugs? Or even .32s? Or even .22s?

The mystery was where the shooter got the gun. How had Vail failed to find it when he cuffed him? The gun supposedly was in the man’s boot, but a Smith & Wesson .38 was too large to hide there. No lawman wanted to believe that Vail had searched the big man and missed the gun. Or, worse, that he had neglected to search him at all. The cafe was full of experts, each with a theory.

Information passed from one table to another. Several men claimed to have been at the hospital when Vail came in. One saw nurses try to put him on a stretcher, which he’d refused. “I can walk,” he’d supposedly said. There was speculation that Vail had even driven himself from Pettus, but witnesses said one of the station workers had done it, with Vail in the front seat of the Hudson and Houston Pruett in the back. Pruett had been nicked by a ricochet (either in the back or the butt, depending on whose version of the story it was). Someone said Pruett wanted the stretcher since Vail didn’t, but he was too heavy.

Such stories would be repeated for decades, with colorful variations. One account held that Vail told the driver that if he didn’t keep the Hudson floored to 110 miles per hour all the way to the hospital, he’d shoot him too.

On any given day, the head table at the American was wherever Captain Alfred Allee happened to sit. The neighboring sheriffs were in Beeville unofficially. But Allee, a Texas Ranger, was here to take charge.

Allee was no stranger to Beeville. During the mid-thirties, he was a regular at the American Cafe, when it was still called the Bluebonnet. That was when Ma Ferguson got elected governor of Texas for the second time and fired the Texas Rangers. The corps was re-hired after the Texas Department of Public Safety was founded, in 1935. Now the Rangers were long past their frontier days, but some veterans were so famous that the bureaucracy gave them wide range. Frank Hamer was one; he had tracked down Bonnie and Clyde. Lone Wolf Gonzaullas was another. Alfred Allee was a third. The mystique remained. Texas schoolboys knew stories of the Rangers as well as they knew stories from the Bible. They knew about the Battle of Plum Creek, in 1840, when fewer than a hundred Rangers skirmished with about a thousand Comanche. They knew about the scrapes in 1842, when 150 Rangers held off the Mexican army during the Republic years. They knew the exploits of Rip Ford in the 1850s, who “chastised” (the term Rangers used for their brutal reprisals) the Comanche and then rode to the border to take on Juan Cortina, the Red Robber of the Rio Grande.

Of all the men in the American, the only one who had known Vail Ennis before he became a lawman was Allee. Some said that Vail had been in the county since he was sixteen, that he had gone to school in Beeville. No one remembered. No one asked. Most men his age hadn’t finished high school. In Texas, a boy had one ambition: to be a man, and most couldn’t wait out high school—there were too many things to do, too much experience waiting.

News from the hospital late Tuesday morning was that Vail had been on the operating table for several hours, and that the slugs had penetrated his intestines. Dr. Edmondson made no predictions, telling the newspaper that it would be another 72 hours before he could tell whether Vail had better than a 50 percent chance of recovering. The sheriff’s wife, Oncie, took this as a signal for optimism. Allee patted her hand and nodded, but Allee was a man of hard experience. He had seen more than a few men die of gunshot wounds since he joined the Rangers. He knew that even a man as tough as Vail had little chance of surviving multiple slugs from a .38 fired at point-blank range.

Allee had come to Beeville to serve as deputy under Sheriff J. B. Arnold. He was the sheriff’s enforcer in those years, when the Depression and the oil boom ran side by side. Roughnecks and rig builders hit the Beeville bars on Saturday night, looking to see who and what they could break. Allee didn’t deal gently with brawlers, the worst of whom were the Ennis brothers, Darwin and Vail.

According to L. D. Hunter, Vail’s hunting buddy, the brothers were originally from Nacogdoches, and they came to South Texas to work as rig builders in the oil fields. “And both of ’em as rough as two bastards could get. They had a fight up on a drilling rig. One of ’em was workin’ up on a derrick and the other one was down on the floor. They got in an argument. Ol’ Vail told Darwin, ‘I’m gonna come up there and whip your ass.’ And Darbo said, ‘No, I’m gonna come down and whip your ass.’ They met halfway and they just fought till they give out. Hung on and fought.”

Rig builders were the paratroopers among oil field workers, and during the week, Vail and his brother fought with a couple of local boys out on the rigs; on the weekends, they came into Beeville looking for whatever trouble was available. Allee said he was the one who told Vail he should go into law enforcement. Allee told the story often that week at the American Cafe, and the men laughed. “I told him, ‘You know more about hell-raisers than anybody. You might as well be on the side of the law.’ ”

Vail’s reputation was well established by 1944, when he first ran for sheriff. Tales of the incredible fistfights had been told and retold. During that first election, some people were already concerned that his temperament was too violent for the job, making the vote count close. Vail didn’t know the outcome until the last box, number twenty, reported at 2:30 a.m. He won by 81 votes.

And though the scene at the American Cafe was a Celtic wake, with stories of hunting and cars, the conversations couldn’t shy away from the issue that loomed over the sheriff and the town. Before Vail Ennis, no Bee County sheriff had ever killed anybody. Vail was actually a deputy when he killed the first time; a mean drunk knocked him down outside a beer joint. There was no question it was self-defense. The second was a big sailor who jumped him at the jail. Then there were the Rodriguez brothers.

The talk always came back to the Rodriguez killings. Two years before, in a shoot-out west of town, Vail had shot down the three Rodriguez brothers: Felix, Domingo, and Antonio, all highly respected farmers. Some people said it was a shooting, not a shoot-out. They said the Rodriguez boys hadn’t fired a gun.

The two men killed by the sheriff at the Magnolia filling station were not highly respected farmers like the Rodriguez brothers. Pat Hines and William Raymond Pittman had spent much of their adult lives behind bars. Hines, the big fellow with the .38, had served a term in the Oklahoma State Reformatory as a juvenile and later did ten years in prison, in McAlester, Oklahoma, for armed robbery. Pittman, who had been sitting by the window of the Mercury station wagon and was the first one out of the car, had been arrested 25 times and had spent three years in a New Mexico prison and three more in Huntsville.

Even as the sheriff lay on what might be his deathbed, the First Baptist Church of Beeville prepared to give Pittman a proper funeral. Six men from the congregation volunteered as pallbearers. Pittman’s father, son, and two sisters came to Beeville for the funeral. They came from far away: Odessa. Fort Worth. Pampa. Oak Creek, Colorado. Hines’s body, on the other hand, was shipped by train to Oklahoma to be claimed by his mother.

Meanwhile, the death watch for Vail lasted four days. At Thursday morning coffee, word went around the American Cafe that the sheriff was awake and talking. At 3:30 that afternoon, the rest of the town was reassured when the Beeville Bee-Picayune was delivered to Turner’s newsstand and people saw the banner headline: “Sheriff Ennis Narrowly Escapes Death in Gun Battle Monday.”

The paper carried a full account of the Pettus shoot-out, confirming some rumors and discrediting others. It reported that Hines’s gun was a .38. That a worker at the station had driven the sheriff from Pettus to the Beeville hospital. That Vail had been shot four times, not five. That Pruett, the station manager, had sustained a flesh wound in the back and had been in the car coming back to Beeville. It also quoted Pruett: “Seventeen shots . . . as fast as I could count ’em . . .”

A few days later, Time magazine picked up the story. The article, which appeared in the November 24 issue, featured a photograph of Vail in a gunfighter pose and ran under a headline that simply read, “TEXAS: Hellbent Sheriff.” It began:

“I am hellbent to keep Beeville cleaned up so a lady can go up the street day or night. I never take but one shot.” Both statements have lisped from the pale, thin lips of Bee County’s Sheriff Robert Vail Ennis. And both statements have been roughly true. Day or night a lady could sashay unmenaced up Beeville’s streets, past the cream stuccoed Kohler Hotel, the Blue Bonnet Café, and the two-story buff brick jail where Sheriff Ennis lives with his wife and daughter and keeps evildoers under lock & key. The roughness in the second statement has been more apparent. In the past four years in Beeville (pop. 7,000), a South Texas oil and cattle town, Sheriff Ennis has killed seven people with his .44 Colt revolver and his .45 sub-machine gun—not all, however, with one shot.

The article also quoted a Beeville resident, who told the magazine, “They might as well have gone out and hanged themselves as to pull a gun on Vail.”

Turner’s newsstand sold its usual hundred-copy shipment in two hours. Another 150 went fast. Across the country, many saw the Time article as proof that Texas was still Texas.

In the days that followed the shoot-out, get-well cards, letters, and telegrams arrived from all across America. Sheriffs, highway patrolmen, city policemen, and FBI agents in Texas and elsewhere wrote personal letters. The police department in Klamath Falls, Oregon, issued a commendation. So did the Bayou Rifles, a gun club near Houston. W. D. Whalen, the governor of the Texas-Oklahoma district of the Kiwanis clubs, issued a citation. The commissioners of Bexar County penned a tribute. A telegram from the Carthage sheriff’s department verged on haiku:

Hold your head up.

We are with you.

A thug is a thug.

Place them one by one.

So many flowers were sent to the Beeville hospital that the nurses had nowhere to put them. Oncie Ennis pleaded for people to stop sending them, but the flowers kept coming. Although the twentieth century was nearing its midpoint, and the Old West was long past, Americans were not ready to let it go. Considering the violent history of the Bee County sheriff, however, the question persisted: Was that a good thing?

Excerpted from The Last Sheriff in Texas: A True Tale of Violence and the Vote, by James P. McCollom. Copyright © 2017 by James P. McCollom. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.

This article has been updated to reflect the following correction: Vail Ennis drove a Hudson, not a Hudson Hornet. That particular model wasn’t available until 1951.