This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

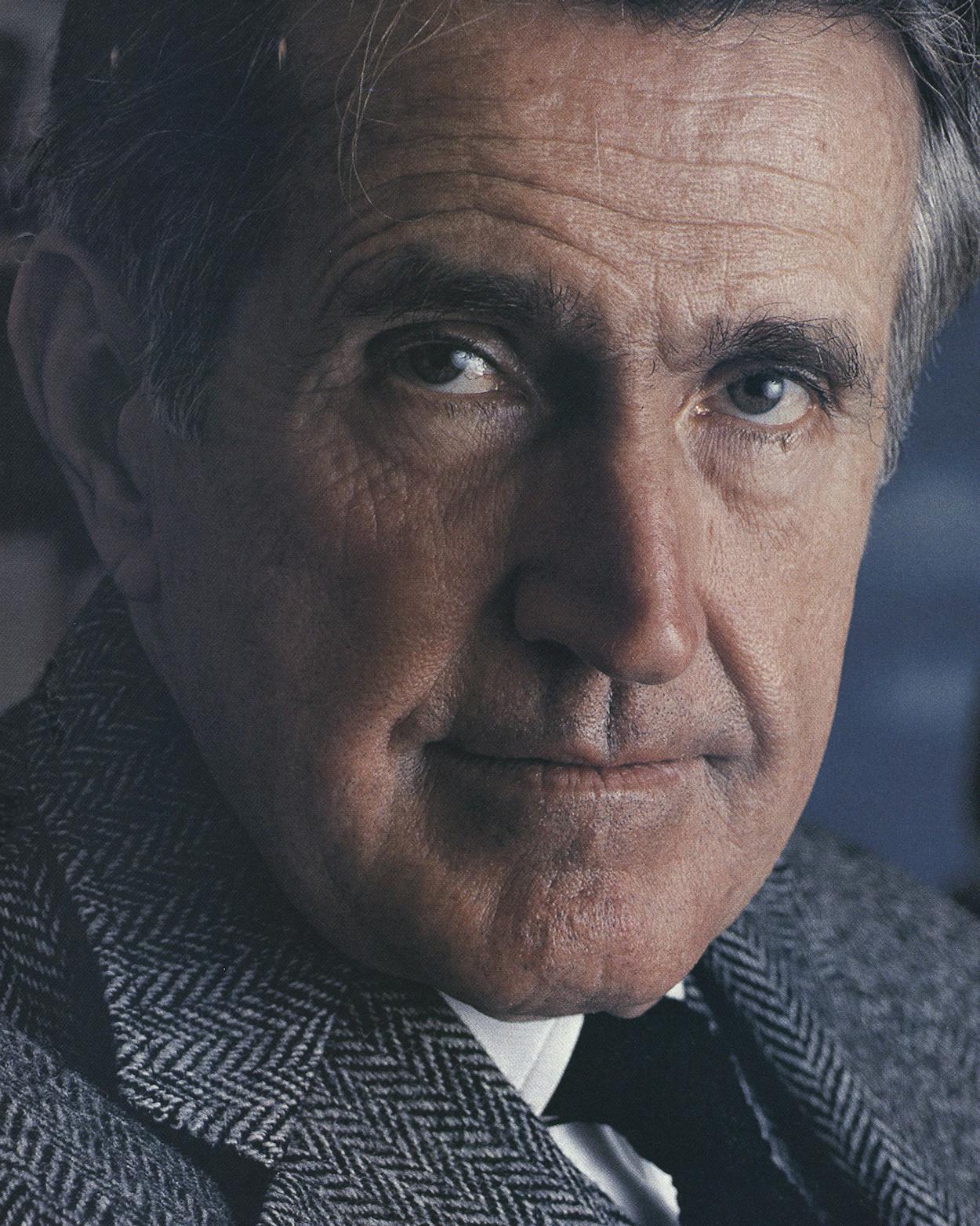

I was standing in the lobby of the American Embassy in London, brooding about how damned superior the British think they are, when Henry Catto, the tall, smooth Texan who is ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, swept into the room. I had just read in the Tatler the kind of infuriating pronouncement about Americans that the British press loves to make—“America has never really found its communal soul”—and it didn’t help that the embassy in which I was brooding is one of the ugliest buildings in London. An enormous pale concrete box just off Grosvenor Square, it mars the otherwise flawless line of graceful old brick buildings, each decorated with a window box filled with vivid red geraniums. The embassy wears the unmistakable stamp of bureaucratic Washington. It looks like a post office.

Catto arrived just as I was mentally ticking off some obvious components of the american soul—competitiveness, the indomitability of the human spirit, the lack of social pretense, the love of honest food—and he quickly reminded me of yet another. When I asked how he was doing, he answered, “My sex life isn’t great, but other than that, I’m fine.” Ah, yes: the all-American sex thing.

Catto’s sex life is suffering because his wife, Jessica, the 55-year-old daughter of former governor William P. Hobby and the sister of Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby, lives most of the time in Aspen, not London. That is also the reason Catto is perceived in the British press as an unhappy man. Private Eye went so far as to describe Catto as a “melancholy soul with a penchant for long silences”—another example of how thoroughly wrong the Brits can be.

Outside Catto’s office on the day I visited was an ominous sign that read: “Threat condition: Alpha.” Immediately I had visions of terrorists storming the embassy, but when I asked Catto about it, he casually shot back, “Oh, nothing to worry about. In security lingo, that’s the equivalent of love and granola.”

In San Antonio, where Catto was reared, and in Washington, where he most recently resided, he is well known for that kind of remark. His sense of humor is very much old school (“I absolutely adore my two grandchildren . . . the thing I like most about them is they are so nice, cuddly, and returnable”), and the nature of his small talk is magisterial (“Don’t bother seeing Miss Saigon while you’re in London. It’s tedious and vaguely anti-American”).

Sitting in a roomy armchair in his office, natty and trim in his suit pants, white shirt, and navy-and-red suspenders, Catto has obvious diplomatic strength: He is a man happy to live in two, maybe even three, worlds at the same time. The three clocks in his office tell Washington time, local time, and Texas time. The sign on his desk, situated in the very capital of the Anglo-Saxon world, is in Spanish. It says, “Silencio, El jefe piensa.” Today the chief is thinking about how much fun it is to interpret America to the British and Britain to the Americans.

There is no theory about a troubled marriage—Henry and Jessica Catto have been the perfect couple for too long.

“This is the premier post in the world,” says Catto, assuming a professorial tone. “When something major happens in the world, we look to the British. There’s a lot of talk now about the emergence of Germany as a world leader, but in fact, Germany is still very much a regional power. Look at what happened when Iraq invaded Kuwait. We immediately turned to the Brits. That’s because the British still think like a world power. Running an empire is like riding a bicycle. You never forget how.”

Henry Catto makes these kinds of erudite mini-speeches all day long. They come easily to him. In fact, everyone who knows Catto knows that this is the job he was born to do. He is the closest thing to royalty that Texas has.

Ten years ago I went hiking with Henry and Jessica Catto and several other San Antonians in the Lake District of England. By day, we walked the mossy English hills and read the poetry of Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Byron. By night, we told stories and idly wondered when—not if—Catto would be appointed ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. By then, he had held the rank of ambassador four times (including El Salvador and U.S. chief of protocol), and his literate, regal demeanor made him seem like a natural for England. It always seemed to me that Jessica—rich, beautiful, ambitious, and rebelliously egalitarian—was just quirky and aristocratic enough to loosen up the British upper class in no time at all. This is a woman who has wash-and-wear hair, despises evening gowns, and is so intellectually restless that she bought a magazine, the Washington Journalism Review, that polices the press.

Catto was born in Dallas in 1930, but his family soon moved to San Antonio, where his father and uncle started an insurance agency, Catto and Catto, which prospered. As a boy, Catto grew up in upper-middle-class Alamo Heights. His family was privileged, and Catto did all the done things in Alamo Heights: graduated from Texas Military Institute, went east to Williams College in Massachusetts, then came home after graduation, took his place in the family business, and eventually married into one of the richest, most powerful families in Texas. Henry met Jessica in 1957 at a dance sponsored by the baronial Order of the Alamo. She was a visiting debutante from Houston, and he wound up substituting as her escort.

They married a year later and settled in San Antonio. In 1960 Henry ran for the Legislature. His political ambition came from a sense of noblesse oblige. One of Jessica’s favorite stories is about telephoning her father, a loyal Democrat, and telling him that Henry was running for office as a Republican. “I always thought,” the former governor told his daughter icily, “that you’d married a sensible man.” Catto’s opponent was Red Berry, a San Antonio gambler who had been indicted for murder not once but twice. Berry ran a single-issue campaign in favor of pari-mutuel betting, but the power of Democrats in those days was such that Berry received 54 percent of the vote. Catto’s 46 percent showing was strong enough to earn him the attention of the handful of other Republicans in Texas at the time. Two years later when he was thinking about running for county chairman of the Republican party, he decided to go to Houston to meet with George Bush, who was the Republican party chairman for Harris County. The two men went to lunch at the Petroleum Club and hit it off. Soon Jessica and Henry Catto and Barbara and George Bush were chummy.

Nearly thirty years later, on December 11, 1988, the Cattos were having lunch at the vice president’s house in Washington, and George Bush pulled Jessica off to the side and asked her if Catto would like to go to England as ambassador. Jessica informed Henry about the offer. “I was flabbergasted,” Catto told me, “but when one of your closest friends asks you to do something like this, you don’t say no.”

It was the classic case of landing the job of one’s lifetime—but at precisely the wrong time. Catto had left government service and was working as vice chairman of the Hobbys’ media company, H&C Communications, which owns six television stations. Not long after his appointment, it became clear that Jessica would not be moving to London but would stay behind in Aspen to build environmentally sound houses (so far she’s built eight) and to preserve part of a 10,000-acre ranch as a wildlife refuge.

So why didn’t Jessica go to London? The Cattos’ circle of friends has at least three working theories. The first is that Jessica is behaving like a spoiled aristocrat. She got one of her heart’s desires; then promptly rejected it as something she never wanted anyway. The strongest evidence for this theory is that she didn’t go to London for Catto’s presentation of credentials at the Court of St. James’s. The second is that Jessica has always had an independent streak, and the decision is just the latest manifestation of that streak. After all, if she were a man, no one would begrudge her for tending to business. The third is that Aspen is just a lot more fun than London, and given a choice, Jessica prefers to be part of the new world, not the old. There is no fourth theory about a troubled marriage. Henry and Jessica Catto have been the perfect couple for so long that any alternative view is simply unthinkable.

“Oh, it works out okay,” Catto says, describing the relationship that has caused such controversy in England. ”Jessica lives with an airplane strapped to her rear end, but other than that, it’s fine. In fact, I think she is changing the zeitgeist over here. A lot of working women identify with her. Of course, a lot of the upper crust think she should be a nonpaid government slave, but here is what I tell them: ‘Jessica Catto half time is better than any other woman I know full time.’ ”

On a typical day Catto operates in the hyphen of Anglo-American relations. Recently he met at nine in the morning with an American businessman who wanted his help selling Apache helicopters to the British government; at eleven he called on Margaret Thatcher to discuss the crisis in the Gulf; at two-thirty in the afternoon he caucused with some American government officials about a proposed European Economic Community directive that would limit imported programming on European television; and at five he left London to attend a meeting of the Trade Union Congress in Blackpool (a city that, he says, “is like Las Vegas without the class”).

“I have felt very welcome here,” says Catto as we drive from the embassy to a residential part of London in his black Opel, “but there is a definite reserve about the British that is difficult for an American. We are just so informal. A small example is that over here you don’t just automatically call people by their first names. I had known Denis Thatcher, the prime minister’s husband, for a year and a half before I asked if it would be okay to call him Denis. He’s a very relaxed and friendly guy, so fortunately he said yes.”

Ahead of us in the front seat with the chauffeur is a security officer from Scotland Yard. Catto goes nowhere without at least one bodyguard. He calls them his nannies. Today when he went on a 32-minute jog through Hyde Park, a nanny went with him. When he spent the night in Blackpool, one stood guard outside his door. “It can be a drag,” says Catto, as we sit in London traffic. “The other night I heard a concert going on in the park by the house, and I thought how nice it would be to wander over and listen, but nanny had gone home, so I didn’t do it.”

Catto has scored two diplomatic coups since becoming ambassador in April 1989. He made a favorable impression on the British by visiting Lockerbie, Scotland, a few months after the crash of Pan Am Flight 103 and talking to relatives of the victims. Then, on the day Iraq invaded Kuwait, Margaret Thatcher and George Bush issued a joint statement condemning Saddam Hussein; as they spoke, they stood together on the front lawn of the Cattos’ Aspen house, which is called Woody Creek. Only a few moments before, Bush and Thatcher had met in Catto’s living room in what is now referred to as the Woody Creek Summit. The tense relationship between Thatcher and Bush (she’s stuffy, he’s relaxed) is routinely placed under a microscope by the British press, and much of Catto’s time is spent easing those tensions, although he’s much too diplomatic to discuss it for the record. Nonetheless, having the two heads of state in his Aspen home was considered a victory.

Soon we are driving by Kensington Palace, where Prince Charles and Princess Diana live. A short while later we stop at a church where Catto is scheduled to attend the funeral of the wife of a prominent London journalist. “Why don’t you come to Winfield House for drinks?” he asks as he exits the car. “I serve the best nachos in London.”

Winfield House is the official residence of the American ambassador to England, and the first thing a visitor there notices is not the magnificent lines of the Georgian mansion, nor the carefully manicured lawns that seem to stretch for miles in all directions, but the Texas flag flying high over the roof. U.S. Representative Ben Blaz, a Republican from Guam, formally protested the flying of the Texas flag over Winfield House, claiming that he fought in World War II for the American flag, not the Texas flag, but Catto says a non-Texan can’t be expected to understand. (He flies the American flag as well.) “I like reminders of Texas,” he explains. ”They make me feel more at home.” For that reason Catto also placed a plywood black-and-white Hereford, made by San Antonian Patsy Stoltz, on the side lawn of his house. “It was my way of saying that the European ban of American beef is naughty,” says Catto. ”Besides, I like this particular cow’s eyes.”

Winfield House was built in 1938 by Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton, and with its cavernous ceilings and elaborate furnishings it looks more like a museum than a house. A uniformed butler named Graham greets guests at the front door and ushers them into an enormous entrance hall. There are photographs of Bush and Queen Elizabeth II and a painting of Thomas Jefferson, in which the framer of the Declaration of Independence bears a striking resemblance to Bob Hope. Graham leads everyone into a huge gold-and-white drawing room, and soon Catto emerges to give us a tour of the house.

“This is the green room,” says Catto, leading the way into another large drawing room. Many of the paintings are from the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, and I asked Catto about how they had come to Winfield House. “Isa [the youngest of his four grown children] called on several museums in Texas and convinced them it was far better to have paintings hanging in Winfield House than in the dusty basements of museums,” he replies. By now Catto has made his way across the hall and is standing in the doorway of a large, glittery state dining room. I ask what he said to the queen when he presented his credentials. He pretends to reenact the official ceremony. “Oh, I was standing here,” he says, drawing himself to attention, “and she was a little tiny woman standing about thirty feet away in another room. I stood at the door like this, nodded, took another step into the room, nodded again, and then looked right up at her and asked: ‘how ya doin’?’ ” His Texas twang was so unnatural to him that he couldn’t execute his line without dissolving into laughter.

Then we crowd into a small elevator and go upstairs to the second floor, where Catto ushers us into the Adams Suite. It’s a bedroom, office, and bathroom—all in soothing shades of lime green and peach sherbet—used by distinguished guests such as the president. What do Catto and Bush do when the president comes to visit? I ask. “Usually we put on our pajamas, have a couple of martinis, and if we’re lucky, we get a half hour to talk,” he says. (Remember, this is a man whom the British press has labeled melancholy.)

Down the hall from the president’s room is a family sitting room, decorated in earth tones by Ralph Lauren, where Catto spends most of his time when he is at home. Next to that is a beige bedroom. “You’ve got to see this,” he says, disappearing behind a door. “I’ve got the largest can in the world.” Indeed he does. His bathroom is as big as most people’s bedrooms, and on its walls Catto has plastered yellow Post-it notes of poems he is memorizing and notes about future meetings.

At seven that evening, the American ambassadors from Canada and Switzerland stop by for a drink, and soon Graham is circulating dainty nachos on a silver tray that are surrounded unnaturally by salmon canapes. The Texans in the room immediately seize the nachos. No one is disappointed. When Catto first came to Winfield House, he had San Antonio caterer Rosemary Kowalski instruct his German chef in the subtleties of Tex-Mex cooking. Catto himself places a nacho into his mouth, swallows it, and says, “Ah, that’s heaven.”

The wife of the ambassador to Canada, a small brunette with beautiful skin, idly places one in her mouth. Immediately she realizes her error. Her eyes grow large, and she starts gasping, sweating, and looking around for a place to spit it out. Finally she comes to her diplomatic senses and swallows the nacho. “My God,” she says, turning an accusing eye toward Catto. “I thought that little green thing was a pickle.”

The conversation turned to how dreary it is that all American embassies are facing budget cuts, how tragic Lee Atwater’s brain tumor is, and how lucky Henry Catto is to have such nice digs. Suddenly, sitting in the gold-and-white drawing room, staring at the plywood Hereford grazing happily on the lawn, I understand completely why Jessica Catto didn’t move to London. It wouldn’t take too many nights of that kind of conversation to prompt serious speculation about the hollowness of power and send you scurrying back to Aspen to do real work.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio