This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Marie was seven years old today, and the sweat was for her. She arrived at the sweat lodge clutching a baby doll and a bottle of Mountain Dew. Gayle Niyah-Hughes, her mother, had brought along a Care Bear birthday cake for afterward and some prayer ties that she had made herself.

“There’s one for me and one for her,” she explained, fingering the little pouches filled with tobacco and sweet grass that would be burned in the fire pit so that the smoke would rise like a tangible prayer. “I don’t make the best ones, but it probably doesn’t matter if they’re not perfect. I just wanted to have this for my daughter. It’ll mean more to her than having a birthday party at Pizza Hut.”

Seven men had gathered to do the sweat and pray for Marie. One of them—judging from the sharpness of his features and the moustache that grew only in two small tufts at the sides of his mouth—was close to being a full-blood Apache. Most of the others were, in varying degrees of heritage, the people I had come to Oklahoma to find: Comanches.

Like many other modern Texans—heirs to the conquest—I could not help regarding Comanches with a romantic cast of mind, as some long-ago blood enemy, as the personification of the frontier itself. The Comanches were the greatest horse Indians who ever lived; they were the wildest people—wild in both the savage and glorious meanings of the word—the plains had ever produced. The Comanches dominated much of Texas from the Edwards Plateau to the High Plains. Though in the end they lost it all, the intensity of their defiance is commemorated in the pitiless and self-reliant Texan character.

In my imagination the Comanches belonged to history, and it was easy to think of them as extinct. They were an emblem of barbaric splendor, and as such it was tempting to believe they had not been subdued but had merely vanished like a prairie wind. But the Comanches did not vanish. They are still around, though much of their old plains culture has long since been destroyed or mislaid. They are a people haunted by the richness and vigor of their past, haunted all the more as each new generation devolves farther away—in language, in blood, in logic—from the ancestral ideal. In that sense, they are like everyone else on earth: a people struggling to recall who they were and to understand who they have become.

When the sun was a little lower, Kenneth Coosewoon, the sweat leader, began taking his ceremonial instruments out of a lacquered-wood carrying case the size of a small toolbox. There were bundles of braided sweet grass, an eagle feather, a gourd, and a deerskin pouch containing sticks of wood that he had found glowing one night on a creek bank. Coosewoon wore a black jogging suit and glasses. His grayish hair was long and tied in back, and a beaded medicine bundle hung around his neck.

In the old days the sweat lodge was an important fixture in a Comanche camp. It was a center for prayer and purification. Before a young man undertook a vision quest or a group of warriors embarked on a raid they would prepare themselves spiritually in the sweat lodge. No one knew any longer exactly what the Comanche sweat ritual had been, so Coosewoon more or less had to improvise. Like many other facets of contemporary Comanche culture, the sweat ceremony was a pastiche of half-remembered lore, gleanings from other tribes, and bits and pieces of Christian dogma.

“I never even dreamed I’d run a sweat,” Coosewoon told me as he gathered his things together. He was the director of the alcoholism center in Lawton, and several years ago he had gotten interested in the sweat ritual as a kind of therapeutic extension of the Alcoholics Anonymous program. He advertised in the paper for someone who knew the old ways and could run a sweat, but no one answered the ad. Then one day he was praying at the creek bank when he saw the glowing wood. The wood was hot to the touch, and at the moment he picked it up he heard a bird shriek and a big oak tree shake in the wind, and then a spirit spoke to him.

“The spirit said, ‘You don’t need nobody. You go ahead and run the sweat. Just be yourself. I’ll be with you all the time to help you.’

“He said everything would come to me, and everything has come to me. I was given stuff little by little. An eagle feather. A gourd. I was given a pipe, but I ain’t never fired it up yet. A Sioux medicine man named Black Elk told me to pray with it and respect it and it will tell me when it’s all right to fire it up. In the old days we would have had a pipe carrier to work with me on it, but we don’t have any of those guys anymore.”

The sweat lodge was made of heavy canvas draped over a cured willow frame. It was a low, hemispherical structure whose entrance faced east, the source of wisdom and knowledge. When it was nearly dusk we stripped down to gym shorts or bathing suits and crawled inside. There was a deep pit in the center, and the bare earth surrounding the pit was covered with strips of old carpet. Dried sage hung from the bent willow poles, and Gail fixed the medicine ties for her and Marie onto the frame above their heads. One by one, seven heated rocks from a bonfire outside were brought into the lodge on two forked branches and lowered into the pit. Coosewoon blessed the glowing stones, brushing them with the braided sweet grass, and then sprinkled cedar over the pit, filling the lodge with its harsh and aromatic smell.

“Grandfather,” he prayed, “thank you for the lives of the people in this lodge. Thank you for the earth and for our Indian people, Grandfather. And we ask your help for all the Indians who are stumbling around drunk, Grandfather, who are not walking straight on Mother Earth, Grandfather. And we thank you especially for the life of Marie, Grandfather, and we pray that you show her how to walk firmly on the earth, Grandfather, and show her how to travel the four directions . . .”

When Coosewoon was finished he said, “Ahoh! All my relations!” and then each person in the lodge prayed in turn. Just when the dry heat from the rocks began to be uncomfortable Coosewoon doused them with water, and we began to steep in the purging humid air. The others’ prayers were direct and unaffected pleas for deliverance—from alcoholism, from broken hopes, from the diabetes that kept loved ones in the Indian hospital, waiting for their legs to be amputated.

“Heavenly Father,” Gayle said when it was her turn. “I thank you for the life of Marie. When I first saw her seven years ago, Lord, I was scared because I know life is so hard, Lord. Lord, I thank you for the life of my husband, even though he’s been gone for three years. I know it’s wrong to grieve over his death, that I should be thankful for what I have, but it’s so hard, Lord. Lord, I ask you to bless me and Marie and my children that are still unborn. Help me to understand the ways of our Indian people. Ahoh! All my relations!”

The sweat took place in four stages, with the participants leaving the lodge every half hour or so to replenish themselves in the cool night air. After each break more stones were brought in, and before the water was poured over them they glowed in the pit, the only light in the utter darkness of the lodge. During the second session Coosewoon sang a song that had been given to him by an old woman a few years before, accompanying himself by shaking a gourd.

“Hey! ya-ya-ya-ya—Hoh! nya-no-nya-no,” or so the song sounded to me, its primitive rhythm oddly complex and familiar. The steam made me light-headed and short of breath. And in that dark lodge, filled with ancient music and the smell of sage and cedar, I found myself entertaining the illusion that the last two hundred years of history had never taken place, that they Comanches were still and always would be the lords of the plains.

In the old days the Comanches knew themselves as Nermernuh, a term that—like so many other self-designations of American Indians—has one simple, confident meaning: “People.” In the sign language used by the Plains tribes, the Nermernuh were represented by a wiggling motion of the hand that symbolized a snake traveling backward. The Utes—their historic enemies—knew the Nermernuh as Koh-mahts, “Those who are always against us,” and it was a corrupted version of that name that finally prevailed among outsiders.

At the height of their power the Comanches presided over a vast swath of prairie, desert, and mountain foothills that became known as Comanchería. They roamed as far north as Nebraska, and their raids carried them as far east as the Gulf Coast and deep enough into Mexico to encounter rain forests and to come home bearing legends of “little hairy men with tails.”

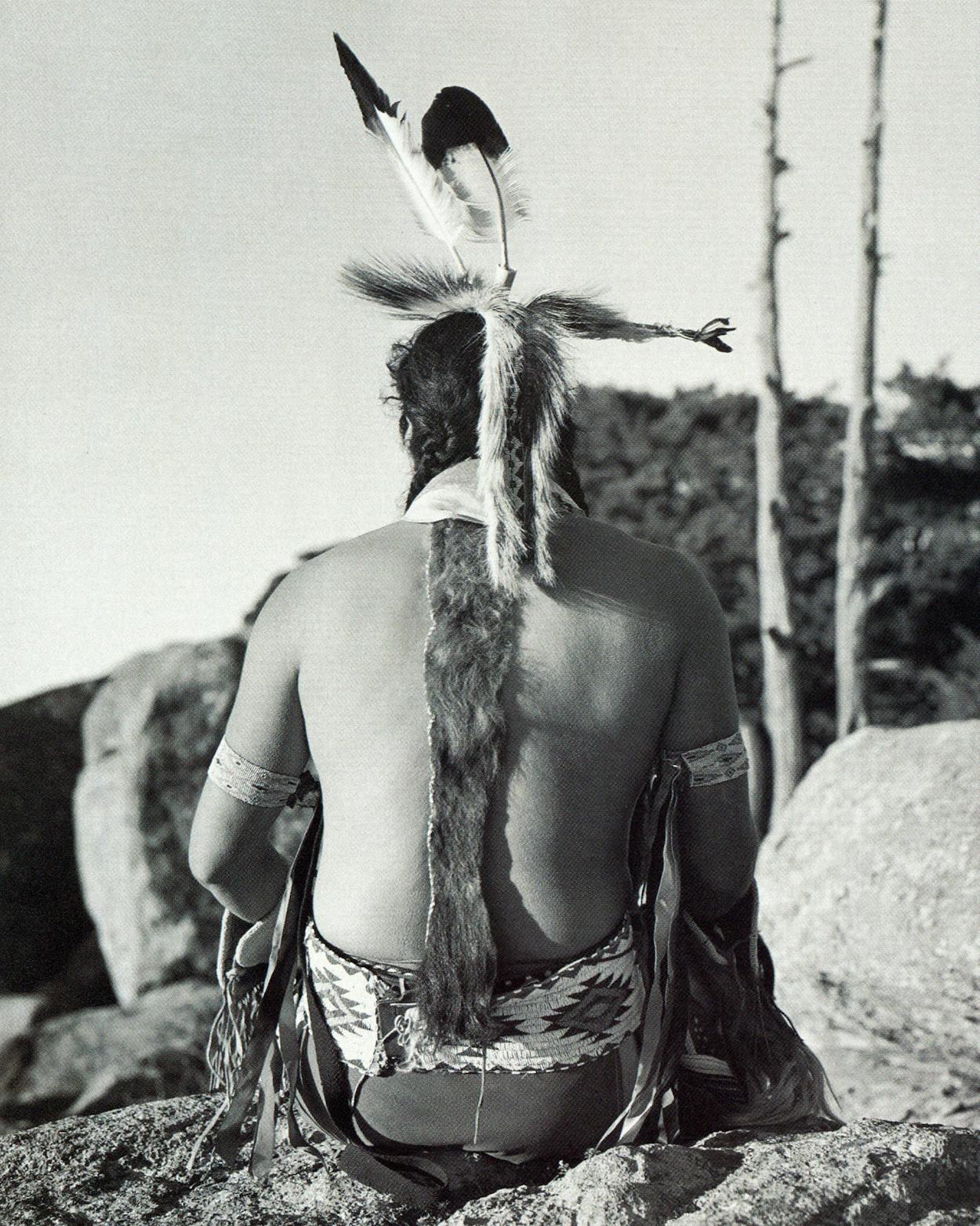

The Comanches were stocky, barrel-chested, prone to near-sightedness. Their faces were broad, with heavy, looming features. The men were vain and superstitious about their hair, keeping it long and greased with buffalo dung, and their ceremonial leggings and moccasins were distinguished by long trails of fringe that dragged on the ground. Comanches filled the cavities in their teeth with dried mushrooms, powdered their babies with cottonwood rot, and directed attention to their war wounds by outlining the scars with tattoos. Boys shot hummingbirds out of the air, snaring them in the split shaft of an arrow. Although there was no prescribed cosmology, the Comanches had a complex and appreciative awareness of a world brimming with spirits and half-glimpsed designs. Unlike other Plains tribes, they did not have an overarching tribal unity. The Comanches were parceled out into bands, and each band was an ad hoc government unto itself, led by men who had become chiefs not through any formal process but through the uncontested power of their personalities.

Long before, when they first filtered down out of the eastern Rockies onto the plains, the Comanches had been just another wandering tribe of bandy-legged pedestrians. But when they encountered the shaggy mustangs that the Spanish had brought to the New World, it was as if they had found some long-missing component of their own identity. The Comanches adapted to the horse with breathtaking commitment. They understood better than any other Indians what a powerful new technology this creature represented. The Apaches, for instance, made only limited use of the horse as a war tool, using it to carry them longer distances on a raid but ultimately dismounting to fight. Comanches fought on horseback, seated on rawhide facsimiles of Spanish saddles or hanging low along the horse’s shoulder, loosing arrows from beneath its neck. They learned to breed horses and became wealthy by plains standards. It was not unusual for a Comanche warrior to have a string of 250 ponies, for a chief to have as many as 1,500.

The horse made the Comanches dangerous, but they had always been predators. Boys became men, and men acquired status, primarily through deeds of war. Texas history is filled with accounts—some bogus, some not—of Comanche savagery. Settlers who encountered the mutilated bodies of their loved ones—the scalps taken, the genitals ripped off, the entrails baking in the sun—were understandably eager to propagate the notion that Comanches were demons who wallowed in the blackest depths of human cruelty. Torture and ritual mutilation were not confined to the Indians, of course. The difference was that white society had learned to fear and scorn in itself the very bloodlust that the Comanches openly celebrated.

For hundreds of years the Comanches held the plains by right of conquest. They were able to keep Spain from establishing an effective colonial claim on Texas, and they fought the more relentless American juggernaut with desperate ferocity through many bitter generations. But by 1874—the year of the pivotal battle at Adobe Walls—it was pretty much over. Most of the bands—their populations halved by disease, their livelihood and morale shattered by the unimaginable efficiency with which the hide hunters were destroying the buffalo—had already retreated along with the Kiowas and Apaches to the reservation at Fort Sill in southwest Oklahoma. Seven years earlier, at the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, a Comanche chief named Ten Bears—who had visited Abraham Lincoln in the White House and had been shown Comanchería on a great globe in the State Department—had made a speech of defiance that was in tone an unmistakable elegy: “I was born upon the prairie, where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the sun. I was born where there were no enclosures and everything drew a free breath. . . . If the Texans had kept out of my country, there might have been peace. . . . But it is too late. The whites have the country which we loved, and we wish only to wander on the prairie until we die. . . .”

The Comanches knew they were living in an apocalyptic time, and they were susceptible to any sort of messianic logic that could fuel their resistance. A young man called Ishatai—whose name translated to “Coyote Droppings”—rose up among them as a prophet. He was credited with predicting the appearance of a comet, claimed miraculous powers, an asserted with conviction what the Comanches most longed to hear: that the white men could be driven from the plains, that the buffalo could be restored, that life as it had always been understood could resume. Ishatai inspired an avenging alliance of Comanches, Kiowas, and Cheyennes. The first objective was Adobe Walls, an isolated trading post a few miles north of the Canadian River in the Texas Panhandle that had been set up to accommodate the hide hunters and skinners who had come south to annihilate the last great herds of buffalo.

Though Ishatai was a spiritual leader, he did not claim to be a war chief. That role, according to legend, fell to Quanah, a prominent young warrior from the Kwahadi band who was destined to become the most famous Comanche who ever lived. Quanah was the son of a chief named Peta Nocona and the celebrated white captive Cynthia Ann Parker. Cynthia Ann had been seized by the Comanches at the age of nine on a terror-filled day in 1836, when the Indians had raided her family’s settlement in East Texas. Her adjustment to Comanche ways was thorough—she married Peta Nocona and bore him three children, including Quanah—but her life was bracketed by shock and heartbreak. After 25 years as a Comanche she was recaptured when Rangers raided a camp on the Pease River. Though Cynthia Ann could speak no English, she broke into confused tears when she heard her name. She and her fifteen-month-old daughter, Topsannah, were treated with kindness, and the Texas Legislature even voted her a pension. But her one wish—to be released back onto the prairie with the rest of her family—was denied. When her daughter died she grieved with the savage intensity of a Comanche mother, and not long after that she herself perished from what has been variously described as a broken heart, a “strange fever,” or self-starvation.

Quanah was a teenager when his mother was stolen from his world. At the time of the battle of Adobe Walls he was about twenty—a cunning, fearless, embittered warrior commanding a force of perhaps seven hundred men who, thanks to Ishatai’s mystical power—his medicine—believed themselves magically invincible. The Indians arrived at Adobe Walls on a warm June night and attacked the collection of sod buildings in the predawn darkness of the next morning. Adobe Walls was inhabited that night by fewer than thirty buffalo hunters and storekeepers, and Quanah had counted on overrunning them while they slept. But the buffalo men had been up most of the night fixing a broken roof support in the saloon, and their wakefulness spoiled the surprise attack. The defenders managed to barricade themselves in time, though one man was killed as he ran for cover, and two brothers, German teamsters who had been sleeping in their wagon, were discovered and brutally dispatched. The frustrated Indians even scalped the teamsters’ dog.

The raid quickly turned into a disaster. The Indians—whose notion of warfare relied on individual initiative and abrupt, feinting charges—were unprepared for a coordinated assault on an entrenched position. The hide hunters, on the other hand, were superb marksmen, accustomed to leisurely potting hundreds of buffalo a day at long range with their Sharps rifles. As warrior after warrior went down, the Comanches and their allies quickly discovered that Ishatai’s protective medicine was a cruel illusion. Quanah himself was wounded. Three quarters of a mile away, at the top of a low mesa, wearing nothing but his yellow medicine paint, the prophet Ishatai sat on his horse, watching the fight. His powers had proven so ineffective that they could not even protect a warrior next to him who was knocked from his horse by a spectacular shot from one of the distant buffalo guns.

After a lingering siege that lasted three days, the attackers withdrew, unable to recover their dead. The buffalo hunters cut off the heads of the Indians they had killed and impaled them on stakes. The alliance that Ishatai had put together fell apart, and though Quanah and his band continued raiding for some months afterward, the medicine was gone. That fall, U.S. soldiers surprised a Kwahadi camp in the Palo Duro Canyon and captured most of the remaining free Comanches. Then they shot their horses. Nine months later Quanah and Ishatai led the People, under army escort, onto the reservation. The trek to Fort Sill took a month. A doctor who accompanied the Comanches and joined them on their last buffalo hunt as free men had the time of his life. “I never felt so delighted,” he wrote, unwittingly memorializing the vanished joys of Comanche existence, “as when mounted on a fleet horse bounding over the prairie.”

“We must have been an ornery group of people.” Kenneth Saupitty, the chairman of the Comanche Tribal Business Committee, reflected as we sat one October morning in his office. Saupitty was, in effect, the Comanche chief, though that title had been retired after Quanah’s death. (“Resting here until day breaks and shadows fall and darkness disappears,” reads his tombstone in the Fort Sill post cemetery. “Quanah Parker, Last Chief of the Comanches.”) Saupitty was 51 but looked younger. His hair was short, with no gray in it, and his cordial, chatty demeanor made him seem at first acquaintance more like a middle manager than the chief executive of an Indian nation.

The chairman’s office is located in a wing of the Comanche Tribal Complex, which sits on a rise just off the H. E. Bailey turnpike, a few miles north of Lawton. The building has the anonymous multipurpose design of a nursing home or a municipal annex. The day I was there, a Ford Aerostar was parked on the lawn, next to a monument that listed the names of Comanche warriors from Adobe Walls to Vietnam. The Aerostar was a bingo prize that was to be given away the next weekend in a game of Bonanza.

There are eight thousand four hundred and ten Comanches. About half of them still live here around the old reservation lands of southwest Oklahoma. To officially be a Comanche, to be counted on the tribal rolls, a person must have a “blood quantum” of at least one fourth. Once enrolled, a member is eligible to vote for the officers of the Tribal Business Committee and to qualify for the various assistance programs and grants that are channeled to Native Americans through the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Comanches no longer have a reservation. It ceased to exist in 1901, the year the federal government implemented the Jerome Agreement, a scheme by which the reservation was broken up for the benefit of white entrepreneurs and settlers who had long coveted the Indians’ land. In compensation, each Indian was given an allotment of 160 acres in the hope that this would force the Comanches to become assimilated homesteaders rather than wards of the government. To a small degree, it worked. Most Comanches didn’t become farmers of their own allotted lands but leased them out instead. For a time, the lease payments provided a reliable economic base, though with each new wave of descendants the per capita value of the original parcels grew more and more diluted. Of greater importance was the fact that allotment, which brought with it a flood of settlement into Indian country, put jobs for the fist time within practical reach of most Comanches.

But whatever prosperity has come to the Comanches has been decidedly marginal. Comanches have all the familiar problems of other Indian peoples, including staggering rates of alcoholism and diabetes. And for all the worldly benefits that came with allotment, nearly half of the Comanches in the Lawton area were unemployed. Those who have jobs—who are fortunate enough to be employed as civilian workers at Fort Sill or as bureaucrats at the Tribal Complex of the BIA—often have extensive kinship obligations that leave them supporting as many as a dozen people on one salary. The Comanches may have lost their reservation, but there does still seem to reside within them the traces of a reservation mentality. Though they never became tillers of the soil as the whites expected them to, they did cease to be nomads. They clung to the old reservation the way their ancestors might have lingered at a dying campfire. The Second World War, in which many Comanches served, helped to disperse them somewhat, but few of the People became wholeheartedly cosmopolitan enough to take on the alien priorities of the white man’s world.

As I visited Comanches I kept sensing a kind of languor, a reliance on certain earthly rhythms that white people do not seem to feel. Many of them were poor, and though they were certainly not poor by choice it seemed to me that as a people they shared a fundamental disinterest in the ideal of wealth. Even the dynamic rhetoric I encountered at the level of tribal government had the air of mimicry.

“I have maintained,” Saupitty was telling me, “that we don’t have a choice as far as economic development goes. We’ve got to provide work in some way. We’ve got a big bingo expansion coming up. We’re moving it into downtown Lawton, right off the interstate access. We’re talking a fifteen-thousand seater. Then we’re going to expand the complex. At this point we’re thinking about an amphitheater, maybe a KOA campground, a store that would be an outlet for souvenirs. We’ve looked at horse racing. Horses and Comanches should be compatible.

“Horses and Comanches,” he mused. “You know, we’ve been told about that by books and movies all our lives.” He looked up at a woman who was passing out agendas. “What about you, Joyce, can you ride a horse?”

“I was thrown off once,” she said. “Haven’t been back on since.”

The old Comanche way of life came to an end with such punishing swiftness that, to an outsider, the Comanches of today still seem to be trying to absorb the shock. At one moment the People were running after wild buffalo on the plains, wolfing down the animals’ raw livers and gall bladders, and in the wink of an eye, there they were on the reservation, wearing shoddy preacher clothes and gouging Mother Earth with plows. If there was ever a group of people not meant to be farmers, it was the Comanches. They chased after cattle on horseback, filling them full of arrows and bullets and then cutting them open and feeding the steaming offal to their children.

Some Comanches, of course, were more flexible than others. Quanah—now Quanah Parker—became a spectacular success in this strange new world and before long was one of the most celebrated and richest Indians in the country. His half-white blood, his regal bearing, and his status as a revered former enemy made him a sentimental favorite among his conquerors. A group of ranchers built him a 32-room house whose roof was painted with giant white stars. He invested $40,000 in a railroad, the Quanah, Acme, and Pacific. He had his own stationery, a per diem for official travel, and even a place in Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade.

In other ways Quanah hewed to his former life. He had numerous wives, and when he was instructed to get rid of all but one he responded by telling the agent to choose which wife he should keep. He had no interest in the teachings of the missionaries—Baptist, Mennonite, Catholic, Dutch Reformed—who descended upon the reservation and instead turned to the “pagan” peyote religion that was becoming increasingly important to the demoralized Indian peoples of the Southwest. Quanah initially opposed the allotment program, but he was still regarded by many of his people as a sell-out, and they remembered that it was the white men who had appointed him chief of the Comanches.

Comanches are individuals, and Comanche politics is therefore contentious and confused. I was never certain, as I listened to accounts of recent tribal history, exactly which chairman had been recalled when, which members of the business committee had used tribal funds to lease Learjets and start fast-food franchises, which officials stood accused of outright embezzlement. Saupitty himself was recalled—illegally, he maintains—during his first term in 1980. In reaction, a group of his supporters seized the complex, charging the originators of the recall with misappropriation of funds and demanding an audit. The standoff lasted six months. Some Comanches applauded the activists and camped out in their tepees in support; others threatened an armed assault. The crisis finally dissolved, but not before the Bureau of Indian Affairs suspended all federal funds until the Comanches resolved their differences. Today the affair—the Comanche Civil War—is commemorated by a small plaque that sits in a stubbly field next to the complex. To read the inscription, one has to crawl through a barbed-wire fence.

Long ago, when the Comanches wandered unimpeded across the plains, they would occasionally happen upon the bones of extinct mammoths. No creature in the People’s experience matched the size of those bones, so they surmised that the bones belonged to the Great Cannibal Owl, a malicious entity that carried off human children in the night. The Great Cannibal Owl was said to live in a cave in the Wichita Mountains, an alluring range of granite, laced with streams and abandoned gold mines, that rises as light as a cloud from the Oklahoma grasslands. The country around the Wichitas has a hallowed, ancestral feel to it, but when you drive through it with a Comanche you cannot shake the feeling that it is, like the rest of Comanchería, a paradise lost.

“Our Comanche people don’t like owls,” Hammond Motah said as he drove around the base of the Wichitas, listening to the muffled bombardment from Fort Sill’s vast gunnery range. “They’re taboo. If my wife and I are at home at night and we hear a screech owl outside, we’ll run out and chase it away.”

Motah managed the print shop at the Comanche tribal complex and also served as the tribe’s public information officer. He wore slacks and gray suspenders, and though he was fluent in PR jargon (he spoke frequently of the need to “develop a format” for my inquiries), the more time I spent with him the more I was convinced that his worldliness was only a veneer. In his late forties, Motah had the classic physiognomy of a Comanche: a stout body and a broad, powerful, contemplative face.

Motah studied elementary education at Arizona State, but he taught only briefly, working instead as a planner for other Plains tribes in the northern states. He came home to Oklahoma as something of an activist (he was one of the Comanches who took over the complex), and he had been deeply impressed by the cultural cohesion he had seen up north. It was a source of great sorrow to him that Comanche traditions seemed to be helplessly slipping away, replaced by a cultural crazy quilt stitched together with borrowings from other tribes. That is, arguably, the inevitable course of any society, but the Comanches were particularly vulnerable. As raiders and nomads they traveled light; they carried their culture in their heads. Their beliefs and manners were existential, rooted in action. Without the sustaining momentum of the open range, they began to collapse.

“We’re really a vanishing race,” Motah said. There was a tear forming in his eye. The Comanche language was dying out. People Motah’s age could understand it but could not speak it fluently, and within another generation or so it would be a ceremonial relic like Latin. Young people beginning to dance in powwows were susceptible to fads and fashions, forsaking the old Comanche dances and taking up the single bustles of the northern tribes. Instead of sitting up all night cross-legged at a peyote meeting, singing the old songs and invoking the old spirits, kids tended to hang out in the parking lot after powwows, drinking and smoking dope. Soon, even the definition of a Comanche would have to be revised. Intermarriage among the tribes had been so common since reservation days that 80 percent of the younger Comanches had no more than one-fourth blood. If they marry someone with less than the minimum blood quantum—a likely occurrence—their children won’t be Comanches. “This is the last generation,” Kenneth Saupitty had told me, “that our constitution will allow.”

Motah himself was married to a Kiowa, and though he and his in-laws got along fine, there were certain Kiowa taboos he had to watch out for. He could not speak directly to his mother-in-law, for example; if he did, his teeth would fall out.

“When it comes to the Kiowas,” he told me, “I’m like a Man Called Horse.”

Earlier that afternoon, Motah and I had visited the Comanche elder center in Lawton, where senior members of the tribe congregated every day for a free lunch. On the paneled walls were framed photographs of famous Comanches—Quanah with his implacable barbarian expression, Ten Bears in spectacles with a commemorative medallion around his neck. A few women in the front room were working at a quilting frame, but the rest of the elders were in the dining room, eating boiled hot dogs, sauerkraut, and canned beets. There were Halloween decorations on the tables. I sat down and talked for a while with an elder who reminisced about his childhood at the Fort Sill Indian School. He had arrived there terrified, not knowing a work of English. If you were caught speaking Comanche, he said, your mouth was washed out with soap.

Soon my attention was seized by a conversation at the far end of the table, where a woman was saying something about Adobe Walls.

“What’d you say?” an old man next to her asked. “Cement walls?”

“No, Adobe,” she said and then turned to me. “You ever heard of Adobe Walls?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “In fact, I always wondered what happened to Ishatai. Do you know?”

“Who?”

“Ishatai.”

“No, I don’t know nothing about him.”

After lunch we dropped in on a man named George “Woogee” Watchetaker, a former world champion powwow dancer (“I retired undefeated!”), artist, and rainmaker. Watchetaker was 72. He had been born in a tent, back in the days when Comanches were still suspicious of houses and the bygone mores of the plains still had some sway. Back then, he remembered, Comanche men still plucked their eyebrows.

“My dad,” he told us, “he made his own tweezers out of a tin. He’d sharpen the tweezers with a file and pull his eyebrows out and his sideburns too.”

Watchetaker himself had a trace of a moustache and a growth of stubble on his chin. He wore glasses with thick black frames and kept his hair in two long braids tied with rubber bands. He had few teeth. His living room was filled with souvenir-shop Indian art—plaster busts of braves and squaws, paintings of wide-eyes Indian children and mounted warriors praying to the Great Spirit.

“Here about 1969,” he said, “I used to be a big drunkard. I used to smoke. The day before Christmas I got tired of it and wanted to quit. I went to bed and watched TV till midnight and then woke up at five-thirty, waiting for the TV to come on again. I was looking out that window when I saw something. It was a figure standing there. It looked like smoke. I wasn’t scared or amazed at what I saw. Pretty soon it spoke to me—‘George, you know what you been doing is wrong. You got a short time to live. But if you change your way of life, you’re gonna be well respected. You’ll live a long time. Your name will go a long way. Remember my words. Listen to me.’

“Then,” Watchetaker said, making a snakelike motion with his hand, “he just slunk away. I didn’t say anything to anybody about what I saw. That evening I played Santy Claus. My craving for drinking stopped just like that.”

Not long after that incident, when West Texas was suffering under a drought, Watchetaker was asked to come to Wichita Falls and make rain. He had never professed to be a medicine man and was afraid to put himself on the line, but the spirit spoke to him again and told him to go ahead and try. He went to Wichita Falls, set a bowl of water down in the middle of a shopping-center parking lot, blessed it, smoked over it, and spit water in the four directions.

“And it hadn’t been a minute before a bolt of lightning shot across the sky and it started raining. Next day they had big headlines: He done it.

“So I remember the words that that vision has told me,” Watchetaker concluded. “I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, and my name has been everywhere.”

That night there was a moon—a Comanche moon, bright enough to light the warpath—shining on the fields as we drove back to Lawton. Motah told me about the time, a few years back, when he had decided to go on a vision quest. In the bygone days a vision quest was the classic Comanche rite of manhood. A teenage boy would go out into the wilderness, deprive himself of food and water for four days and nights, and wait for his “visitor,” usually an animal spirit who would issue instructions and leave the boy with a personal fund of mystical power—his medicine.

For his vision quest, Motah picked a site near a spring and made a circle of sage. He remembers being strong and confident the first day, but by the second day he was so thirsty he could not refrain from licking the dew off some nearby leaves. After a time his parents, both of whom had died years before, appeared to him, pleading. “You don’t have to do this,” they said. “Come with us.” But he stayed in the circle. He was taunted by a group of nenuhpee, sinister apparitions that take the form of tiny warriors and are also know to modern Comanches as leprechauns. “You’re a fake,” the nenuhpee jeered. “You don’t belong here. You don’t know anything about the old ways.” Several more visitors appeared—some benign, some malevolent—but before the prescribed four nights had passed Motah was so hungry and sick and scared that he crawled out of his circle.

“I went home and slept for two days,” he said. “I went to see a medicine man to tell him about my experience. He was extremely interested. He said he hadn’t heard of a Comanche going on a vision quest for fifty years.”

At the Comanche elder center I had been introduced to Thomas Wahnee, a 77-year-old retired roofer who was born, he told me, the year Quanah Parker died. Wahnee was a quiet, modest man who gave the impression of being subtly amused by everything he saw. He wore dark glasses and a hearing aid, and a single incisor dangled precariously from his upper jaw. Wahnee was a peyote man. Like many other elders, he had grown up in the Native American Church, attending meetings back in the days when participants still wore buckskin shirts and tied their braids with otter fur. Not all Comanches, of course, followed the peyote road. Most adhered to some variant of traditional Christian worship, while others found spiritual expression by participating in powwows. But the Comanches were the first Plains Indians to acquire the peyote religion, and they played a major role in its dissemination.

Wahnee invited me to attend a meeting of the church, and one cold winter evening I arrived at his house. A growly pit bull was chained up at the side of the house, and in the back yard a tepee stood next to a stock fence.

Ten people, mostly men in their sixties, had gathered for the meeting, and we sat around in Wahnee’s house until late in the evening listening to tales of power and witchcraft and medicine. When the fire was built Wahnee and the elder men led the way into the tepee, carrying their toolboxes (containing gourds and feather fans and other paraphernalia of the peyote rite) like men going off to work a late-night shift at a factory. We circled clockwise around the outside of the tepee and then went inside and sat down on sofa cushions on a bed of sage.

Wahnee, as the leader, sat to the west of the earthen fire ring. The fire ring was in the shape of a crescent, the ends pointing east. In classic peyote symbology, the crescent represented the path of a man’s life from birth to death, but over the years the religion had taken on an admixture of Christianity, and the shape of the fire ring now symbolized, as well, the hoof print of the donkey that Jesus rode into Jerusalem.

When everyone was settled, Wahnee brought out the sacrament—Father Peyote—and placed it on the fire ring. It was a gray, wrinkly nubbin of cactus, ugly with knowledge and medicine. Wahnee then passed around corn shucks and a bag of Bull Durham tobacco, the makings of the ceremonial cigarettes that were to be smoked during the evening’s first prayers.

After the smoking and the praying Wahnee distributed a leather bag of peyote buttons and a vial of peyote powder. I ate one button, enough to be polite, and swallowed some of the powder, afterwards rubbing my hands over my head and body as the ritual mandated. The bitter taste almost made me gag and the peyote sat uneasily in my stomach, but I began to gaze contentedly at the perfect glowing coals of the fire.

Then the singing began. Wahnee sang four songs, holding a staff and eagle feather in one hand and shaking a gourd with the other. He was accompanied by a drummer who pounded out a stern rhythm on a No. 6 cast-iron kettle that had been half-filled with water and hot coals and then covered with a taut deer hide. Thus constructed, the drum was a little model of Mother Earth herself, a reverberant fusion of water and fire.

When Wahnee had finished with his songs he handed the staff and gourd and eagle feather to the man on his left. Each participant sang four songs, and when the circle was completed they began again and then again. It went on for five or six hours. I stared at the fire, trying to locate some sort of tonal entrée into the music, but all the songs sounded indistinguishable to me. Nevertheless, I felt bound up in them somehow, and when each one ended I experienced a tiny wave of sadness along with the sensation that the temperature in the tepee had dropped a few degrees.

At two in the morning Wahnee sang the midnight song—about a band of Comanches long ago who had lost their horses and, while walking along a creek, killed a bear—and then he left the tepee to blow his cane whistle. He blew the whistle in each of the four directions, announcing to the world our prayerful presence there in the tepee. The notes he produced were so sharp and resonant it seemed that they were reaching us from the rim of the earth and that Wahnee himself had been transformed into some sort of magic bird.

When he came back he walked clockwise around the fire and took his seat again in front of Father Peyote. The singing and praying began again and went on for another three hours. At the next interval I asked Wahnee, according to protocol, for permission to leave the tepee for a moment. He nodded his head good-naturedly, and I stood up and made the circle to the east, taking care not to make the mistake of passing in front of anyone who was smoking and eating peyote. The fireman held the flap open for me as I walked out into the night, the songs commencing again behind me. The night was very cold and the sky was clear. There was dew on the grass and it glistened in the starlight. I was not supposed to go back into the tepee until there was a pause in the singing, so for a long time I just stood there and watched it. The tepee’s canvas skin was transparent, and the fire pulsed inside it like a beating heart, in time to the drum and the voices.

I wondered for how much longer such vibrant remnants of the old Comanche life would endure. During the time I spent in Oklahoma I kept hearing about someone who, at least in theory, seemed perfectly poised between the Comanche past and the Comanche future. He was a great-grandson of Quanah Parker, and he had gone to Hollywood on a “sacred mission” to make a movie about his ancestor.

I met Vincent Parker for dinner at Chaya Brasserie near Beverly Hills. He would not tell me his age (“That’s my secret,” he said defiantly. “I have held onto that one little sense of mystery”), but he looked about thirty. He was wearing a Giorgio Armani suit with a matching tie and pocket square, and he carried a topcoat draped over his arm. His olive skin was smooth, and his hair was fashionably long and tousled.

Sipping a glass of red wine, he studied the menu. “I think I’ll have the shrimp ravioli,” he told the waiter. “The only problem is I hate to change wines.”

Parker closed his menu and regarded me with an emphatic gaze, blinking incessantly, as if there was something wrong with his contacts. “I’m a living example of what Quanah Parker wanted,” he said. “I am in some respects what he envisioned for his people. He wanted them to retain not only their identity but also to be at ease in this dominant society.”

Vincent said he was the great-grandson of Quanah and Chony, the chief’s first or second wife, depending on which scholar you accept. He had grown up in Lawton in a family with eleven brothers and sisters. His parents—who had the good fortune to strike oil on their allotted land—instilled in their children the Parker ambition to master the white man’s world.

Vincent graduated from the University of Oklahoma, worked for a time as an aide to Oklahoma Governor George Nye, and dabbled in tribal politics, running unsuccessfully for vice chairman after the 1980 takeover. He was keenly aware that his ancestor presided over all his endeavors.

“I told my father I felt different from any of my brothers and sisters. My father said, ‘You are different. When I look at you, I see him.’ ”

That was powerful medicine. To a Parker, Quanah was hardly a typical mortal.

“He was a way-shower,” Vincent said as the waiter brought his shrimp ravioli. “The Christians had their Jesus, the Indians had their Gandhi, and the Comanches had their Quanah Parker.”

Vincent had the feeling that he was meant to be a way-shower too but wasn’t sure how he was to accomplish it. He spent a lot of time in the Star House, Quanah’s famous residence, sitting in his great-grandfather’s chair and praying for guidance. One night his mission came to him: He would write and produce a play about Quanah. He secluded himself in the Star House to write the script, and when it was finished he blessed it by fanning cedar smoke over it with an eagle feather. Nine months later, the play premiered as an outdoor pageant in Quanah, Texas, with members of the Parker family making up the cast. The pageant ran for five years, and then Vincent moved to Los Angeles to pursue the goal of commemorating Quanah in a feature film. Bankrolled by his family, he traveled west with a sense of sacred purpose and a wish list. (“Before I left Oklahoma,” he said, “I wrote in my journal that I wanted a Gucci watch. I love black and gold. The first day in L.A., I went to Gucci and bought it.”)

During his time in L.A. Vincent has worked in various post-production positions for Disney Studios, learning the industry to prepare himself for his task. With his remarkable tenacity and focus, he has already begun to beat the odds. A documentary on Quanah that he produced has just been completed, and he has come close to putting together the funding for a feature. In his spare time he has dabbled in modeling and has been hired to appear in a commercial for Jeep Comanche, in which he will face the camera and say, “Comanches. My forefathers led them. Now I drive them.”

“Sometimes it’s hard,” he said. “I’ll call my father and tell him I have no energy. I get tired of playing the social circuit, putting up with the Hollywood bullshit. At any given moment I question it. I can understand how Jesus wept and questioned his own mission.”

On the other hand, it’s not so terrible. “Going to dinner at Spago, Le Dome, and Nicky Blair’s. That’s my world. I love the wonderful cultural activities that are afforded to me here. People laugh at me because I spend so much time at Tiffany’s, but there are so many wonderful things there! I give no apologies for being driven in a chauffeured limousine. Quanah himself had a surrey with silver trim. If he were here today he’d be with me in the limo. What made him effective is the spiritual influence he brought about. If anything, that’s what I’m trying to hold onto.”

After dinner we walked down the street, toward the Beverly Center, talking about the Adobe Walls song that Quanah had written after the battle and that was one of the few surviving Comanche songs from pre-reservation days. It was a song of mourning, a song of loss.

“I do intend to protect the integrity of this project at all costs,” Vincent said, returning to the movie. “I tell producers, ‘You’re going to continue your careers in L.A. I’m not. I’m going back to these people in Oklahoma, and no amount of money could compensate me for the damage I could do. I cannot sell out!”

I stared frankly at this improbable person. He may have been just another Hollywood hustler with a messiah complex, but I didn’t think so. Beneath his fashion-plate exterior, there was something steely about him, and it was not hard to imagine him in another time as an arrogant and fearless warrior, a lord of the plain.

“I’m not playing around out here,” he said with sudden passion as the Beverly Hills traffic surged by us. “I’m on the warpath.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads