This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In Houston there are mere murders and then there are Big M’s. You read about Big M’s on the front page of the newspaper, story after story bannered there because Big M’s always involve rich people. In one of those large houses around town something has gone wrong. And what goes wrong has to do with a woman. She may be the murderer or the victim, but as the details of her life come out day by day in the news, it gets progressively easier for people in Houston, their nerves frayed by the sweltering heat and another evening’s claustrophobic trip home along the freeway, to believe that the opposite of love isn’t hate. The opposite of love is murder.

This case looked a little different at first. The two would-be hit men from California botched the job. They put four bullets into the flashy blonde in the red Firebird, but they didn’t kill her; they left her paralyzed from the waist down. And the scene of the crime—the parking lot of a doughnut shop on the corner of Beechnut and Gessner—was a long way from River Oaks, the setting of most Big M’s in the past. But this murder attempt became a Big M as soon as the young victim mumbled the name “Mimms” into the ear of an attending cop. The police, the press, and the public would quickly learn that “Mimms” was meant to be “Minns,” as in Houston health spa magnate and self-styled adventurer Richard L. Minns.

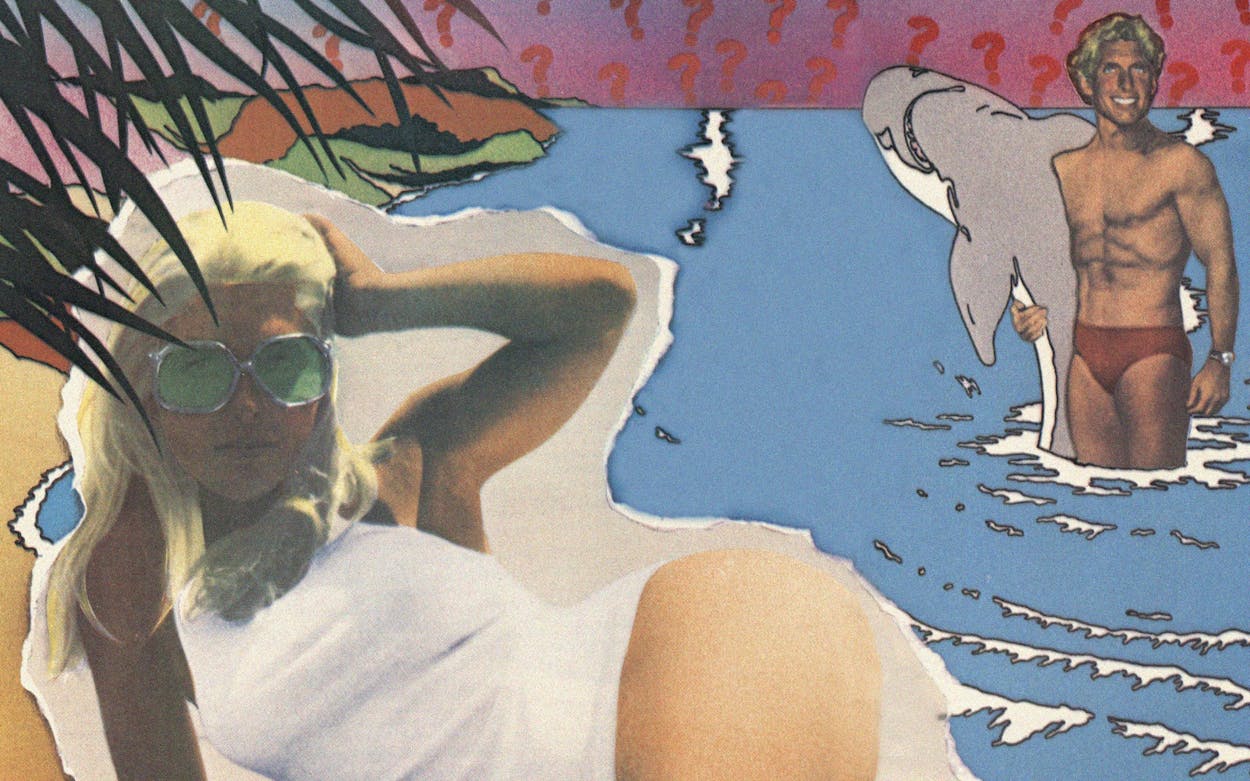

They had been lovers for three years. They were both bottle blonds, but otherwise Dick Minns and Barbra Piotrowski didn’t seem to have much in common. She, like her attackers, was from California, just 26, a surfer, the kind of summer girl the Beach Boys (“Bar-Bar-Bar/Bar-Barbara Ann”) taught a generation how to pine for. He was almost twice her age, an entrepreneur, a promoter, and a self-made millionaire. He had rakish wavy hair, a polished smile, and the physique of a body builder. In defiance of growing old he staged stunts on his birthdays—hunting a great white shark or waterskiing for hours around Lake Tahoe. And maybe taking a young mistress was another way for him to defy growing old; plenty of other men have done the same.

But there was more to it than that. Theirs was a romance born of a modern subculture—the double-knit aristocracy. Double-knit aristocrats make their money fast and without any help from the oldline downtown crowd—in raw land and franchises and shopping centers and health spas—and in middle age they take to spending it in Aspen and Acapulco and Puerto Vallarta. They learn how to ski and play tennis and scuba dive. They trade in their trusty Chevys for 450SLs, their three-piece suits for rhinestone denim ensembles, and their Scotch and water for more exotic mixtures. In the swirl of new money, new habits, new friends, it’s often a logical step for them to leave their wives for younger, freer women. The double-knit aristocrats live with a certain vengeance. “I’ve made it and I want everything now” is their motto. So it’s no surprise that their world is filled with sudden crashes, wrecked lives, and violence.

In the wake of the October 1980 shooting, Dick Minns’s years of tireless self-promotion in Houston made him the natural center of attention in the press, even though no hard evidence linked him to the crime. He has not even been questioned by the police. From Barbra’s point of view (or what can be gleaned of it from affidavits, depositions, and her court testimony—she isn’t talking to reporters), it is only right that suspicion should fall on Dick. To Minns’s defenders (Minns himself isn’t talking either), her claims are merely the puny revenge of someone whose shady past came back to haunt her and who is now trying to blame her lover. It is this conflict between the double-knit aristocrat and the California girl, these two opposite poles of the same magnet, that created a charged field around the shooting, that made it a Big M.

Richard L. Minns was at an odd juncture the January morning he met Barbra Piotrowski on the ski lift in Aspen. For twenty years his life had been dedicated to—obsessed with—making money; during that time he’d built a $10 million personal fortune from a six-state, 32-facility chain of President’s First Lady Health Spas. He’d indulged himself in all the basic trappings of newfound wealth in Houston: a mansion on Memorial, a chauffeured Cadillac, a condo at the Lakeway resort near Austin. But toward the mid-seventies, as he approached the age of fifty, he’d become more than a little bored with it all. With the Federal Trade Commission cracking down on the spa industry in general, he’d probably taken the venture as far as it could go. It was time to find new challenges, to live a little.

As for his personal life, friends later said that Minns’s decision to gradually liquidate his spa business caused him and his wife, Mimi, to drift apart. President’s First Lady, after all, had been as much Mimi’s baby as Dick’s: he was the creative torque behind it, the idea man and the salesman; she was the common sense, the one who kept things running smoothly. It had been a successful marriage in business, but lately, as Minns would admit during the divorce proceedings, the romance had all but vanished.

Barbra Piotrowski, for her part, was flattered by the aggressive advances of the handsome, muscular man from Texas, but she just wasn’t in the mood. She was a Californian, a registered nurse with dreams of becoming a doctor, and at the moment wary of men. Dick Minns persisted. He would sometimes literally chase her down the mountain as they were skiing; occasionally he would wipe out on the slopes (in spite of his marvelous physique, he wasn’t nearly the skier Barbra was). He told her that he’d recently been through a divorce, and Barbra believed him.

After she returned to her home in Los Angeles the handsome Texan called her frequently to chat. They eventually agreed to meet in Aspen again in March. As Barbra said later in an affidavit, “During that trip we fell in love. He asked me to move to Houston. . . . I had never been in love like this before—I didn’t know if I ever would be again—so I decided to move to Houston.” Barbra packed her bags and headed east.

Dick Minns showered his new mistress with the best his considerable fortune could buy: he paid her moving expenses to Texas, installed her in a fancy apartment in Westbury, and provided her with ample spending money. Soon he began staying at the apartment several nights a week. To explain his absences, as Barbra later recalled it, he told her that his ex-wife had a “very large home and that he needed to entertain some out-of-town businessmen there for a few days.” Apparently he was telling his wife, Mimi, a similar story. During the divorce proceedings Mimi Minns testified that when her husband left home for a day or two during this period, it was always on the pretext of out-of-town business.

Barbra and Dick would jet off to some exotic resort virtually every other week. Between March 1977, when Barbra moved to Houston, and November, they traveled to Aspen (twice), the British West Indies island of Antigua, Lakeway (twice a month, Barbra says), New York, Los Angeles, Lake Tahoe (twice), Vail, and Acapulco (twice). In return, Dick required complete devotion from her. Though he agreed to her enrolling in pre-med courses at the University of Houston, Barbra quickly found that his demands made it impossible for her to continue her studies. She was so often out of town that she missed too many classes, and even when she was able to attend classes, as the months passed, Dick became so jealous of her attention to her course work that she took to studying behind the locked door of the bathroom.

The love affair was forcing her to live a dual existence. One part of her was still an aerospace engineer’s shy daughter from Los Angeles, a conservative, single-minded young woman with definite goals and few distractions. At the same time, Barbra Piotrowski the mistress was rapidly taking over the old personality. She became Dick’s favored model in newspaper ads for the few health spas he still owned. He wore her proudly on his arm at Houston’s finest restaurants. They lived in a kind of dream world—a world filled with Halston gowns, Mercedes SLs, fancy jewelry—and it was impossible for Barbra Piotrowski to resist it.

To the double-knit aristocracy Dick and Barbra exemplified the best that the world of new money had to offer. The couple cut a dashing, romantic figure—they were a perfectly matched set of bronzed, blond beauties, muscled, healthy, and sparkling. And consciously or unconsciously, they started playing to their audience. Dick began to replace his suits with outlandish denim outfits; Barbra had always been almost self-consciously plain, but with Richard Minns she was voluptuous and sultry. Some friends later said that she remade herself in the image she thought he wanted. A Minns-Piotrowski Christmas card featured a silhouette of the two embracing before an Acapulco Bay sunset.

Barbra was the second of four children born to Wes and Stella Piotrowski, Polish immigrants who passed on to their children simple, no-nonsense values. She had always wanted to be a doctor, an ambition her square-jawed father endorsed. She was a good student, with a keen memory for facts and a curiosity about science. The same single-mindedness applied to athletics: she was a proficient diver and skier and seemed to have been born with the athlete’s sense of internal discipline and competitiveness. More than anything else, though, Barbra was always Daddy’s little girl. Wes Piotrowski sheltered his eldest daughter. He handled her financial affairs, even when she was grown and on her own, and later, when she took up with the rich Texan, he would help her with her homework—long distance—because she seemed so preoccupied.

It was a singularly unnotable childhood until, during her early teens, Barbra had her first experience with violence. After riding on a float as a beauty queen in a holiday season parade in Hollywood, she was accosted at gunpoint by a man who took her off to the mountains and raped her.

She later told a friend that the experience made her want to “punish” men, but sometimes it seemed that she really wanted to punish herself. She got mixed up with drugs and eventually was picked up at her Catholic high school in Mar Vista for attempting to sell pills. The arrest record says she had needle marks on her arms. She also ran with some tawdry types. She opened a small antique shop with a man who was eventually busted for passing counterfeit money. Barbra said later she was “ashamed” to have known him, and in a couple of years she was back to her old self—earning an L.V.N. at Marina Mercy Hospital, an R.N. at UCLA, and taking pre-med courses.

While working as a nurse Barbra met Dr. Paul Berns, a Beverly Hills internist. Both of them later characterized their relationship as a friendship that grew more out of their mutual interest in medicine than out of love. But it was still Barbra’s first serious fling, and when they broke up in 1975 she was despondent. A year or so later she met Dick Minns.

The day Barbra found out that her lover was married, as she recalled during the Minnses’ divorce proceedings, “I thought I would die. He said he and his wife were separated and had an open marriage, and that this had been the case for many years. He told me that approximately five years before, he had lived with another woman and that his wife was fully aware of this and didn’t care, and that he’s had different girlfriends over the years. He said he previously lied to me because he loved me so much that he would have done or said anything to convince me to move to Houston. He said that his wife knew about me and that she had even met me and that she didn’t care, as long as the money kept coming in. I was in love with Dick. I accepted his explanation.”

But the thought of another woman in Dick’s life made Barbra intensely jealous. It irritated her sense of loyalty and fidelity. Her account continued: “I don’t sleep with anyone. He doesn’t sleep with anyone. And by that, I mean have any sexual relations. And I’ve asked him, ‘Not even your wife?’ That was one of the conditions [of the affair].” Dick became so obsessed with convincing Barbra that he wasn’t having sex with his wife that one day, as she remembered it, he told her, “I’ll call Mimi and you listen in on the other phone and I’ll prove it to you.” With Barbra listening, Dick said to his wife, “We’ve had four kids together and things couldn’t have been that bad, were they?”

“Yeah, that’s really funny,” Mimi shot back.

“Well, that didn’t happen without sex.”

“But the last one happened sixteen years ago,” she said.

“You’re trying to say that we haven’t had sex for sixteen years?” Dick baited her.

“No, but it’s been several years,” Mimi said.

After they hung up, Dick gave Barbra a big hug and said, “See?”

Mimi Minns, for her part, was hardly pleased to find out that her husband had a mistress. According to her deposition for the divorce proceedings, she first became suspicious in September 1977, when she received in the mail several pictures of Dick and Barbra at Snowmass, Colorado. Then one day, while shuffling through some of her husband’s papers at his office, she found a mysterious address on Arboles in Southwest Houston. “I had to see if what I thought was true,” she said. So she drove home and called Dick back at the office to see if he would be coming home that night. He told her he was going to work out at one of the spas. That evening Mimi went by the spa to see if his car was there. It wasn’t. She set her jaw and drove to the address on Arboles.

She knocked on the door several times and yelled, “Help.”

Barbra opened the door and said, “Stop screaming. People are turning on their lights. You’re making a scene.”

Mimi Minns said, “My husband is in your house.”

“He’s in the shower,” Barbra said. Mimi said, “I don’t care where he is. I’ve seen him naked before. Tell him to get down here now.”

According to Mimi, Barbra then slammed the door in her face; after she beat on it several more times, Dick answered, still dripping from the shower. She told him she wanted to talk to him at home. When Dick arrived at the mansion on Memorial he told her, “I wasn’t there.”

“I heard that story once before,” Mimi said, referring to an earlier affair Dick had refused to admit to for nearly twenty years, “but this time I saw you. I want a divorce.”

With his business in gradual liquidation, the last thing Richard Minns wanted was a divorce and a nasty community property battle. He hatched quite an innovative plan for reconciliation. He had his lawyer draw up a legal contract of open marriage. According to the terms of the contract, he and Mimi would each take $100,000 from joint assets to do with as they pleased; they would set up separate households; sexually, they were each completely free to do whatever they wanted. The only real restraint was that they stay legally married, which protected their fortune. Mimi decided to sign.

The open marriage contract with his wife was a case of Richard Minns’s having his cake and eating it too. Life was a series of skirmishes for him, but the difference between him and most other men was that he usually won. Friends—and even enemies —attributed this to his natural charisma and charm, his almost evangelistic powers of persuasion. But it more likely had to do with another fundamental element in his personality: an unwavering determination to have the upper hand, to win; an insurmountable competitiveness that made each and every little argument, conflict, act of disloyalty, or snide joke a direct call to arms.

Richard Minns was always his parents’ favorite—his sister later said that the folks thought “he was Jesus.” He had a nomadic middle-class upbringing. His father was a jack-of-all-trades hustler and salesman; the family lived in Temple, Granger, Taylor, Allen, San Antonio, and finally Houston as Dick’s father moved from the ready-to-wear business to sporting goods to real estate.

The young Dick Minns was somewhat overweight, bright and precocious, a promoter and a prankster, an instigator even in those days. A good friend would later say, “He was no more mischievous than any other young boy,” but his sister, who is currently at odds with Minns in a probate suit, says that at times his pranks and yearning for the limelight went to excess. When he was young, she says, he would pick on the “punk” of the block by stripping him naked, locking him up in a chicken coop, and charging admission from other neighborhood kids to come tease him. But there was a softer, more artistic side too: he loved to entertain and had an innate flair for drawing.

He attended San Antonio public schools until he reached high school, then went to two military schools, Peacock Military Academy and the Texas Military Institute. The academies were a disciplinary measure by his parents and a successful one. Dick trimmed down, took up body building, and made consistent A averages, according to school records. He eventually was named neatest cadet in the sophomore class at Peacock.

He graduated and attended the University of Texas, where he majored in journalism. He worked for both the campus newspaper and the magazine and is remembered by a friend as “hardworking” and a lover of pranks. While finishing his journalism degree, he met and married Mimi Levy. After his graduation in 1950, he moved to Houston and went to work for the Houston Chronicle as an advertising representative for the paper’s Sunday magazine; by 1953, he was the ad manager, though according to Mimi, the young couple had to struggle to make ends meet. After the birth of their first child, Cathy, Dick quit his job at the Chronicle to start his own advertising agency. The family moved into an apartment in Montrose and opened the agency in a small storefront just down the block.

It was just the two of them, and by Mimi’s admission, they got off to a rough start. Dick dragged some of his clients from the Chronicle over to the All-State Advertising Agency, but it wasn’t until he began doing ad work for American Health Studios that the business really took off. Dick seemed to know instinctively that people wouldn’t part with their money for a health club membership unless, in the process, they were buying some kind of dream. He knew how to create that dream—using himself as the example.

In 1956 he got his big break. American Health Studios, his major client, had fallen on hard times; the company had expanded too rapidly and oversaturated the market. Among its many creditors was All-State Advertising, which was owed roughly $250,000. An idea formed in Dick Minns’s mind: why not take over a few of the studios in lieu of cash payment for the debt? He knew he could succeed where they had failed; all it would take was a little persistence and a lot of hype.

In 1956 Minns took over five of American Health Studios’ facilities and renamed them ace Rican Health Studios. He was a natural promoter who knew that the only way to make money in spas was to spend it on advertising; he was also an energetic gadabout who quickly managed to have his name appear frequently in newspaper social columns. He had a sense of how and when to expand. Associates and even competitors to this day say they’ve never seen a better start-up lease negotiator than Dick Minns; his chain of spas—again renamed, this time President’s First Lady—would eventually grow sixfold and stretch through half a dozen states. And the company’s finances were healthy enough, even at the height of expansion, for the enterprise to go public.

In addition to salesmanship, Minns was responsible for one other great idea in the health spa business. He revolutionized the art of financing a contract. When would-be patrons filed in to give, say, $50 down and $50 a month for three years, Minns wasn’t really gambling on the customer’s solvency: he got $650 up front because he sold all the contracts to a finance company. If the patron had problems making his payments, the finance company could handle it.

Minns wasn’t without his enemies. There were some who came to see his notorious persistence as obnoxiousness, his flamboyance as just so much hot air. One was Robert Swartz, a young spa manager for Minns, who, after a falling-out with the boss, left the company and made plans to start up his own chain of spas.

Swartz scraped together $10,000 and started what later became the Slenderbolic Health Spa chain. Almost immediately he and Minns were at each other’s throats. In 1964 Minns filed suit against Swartz, alleging that his competitor was “raiding” his employees; Swartz countered with similar allegations against Minns. It was the beginning of a decade-long legal row.

As the months dragged on, the two filed and counterfiled allegations of copyright infringement over the advertising slogan “What have you got to lose?” In late 1967 Swartz added allegations that Minns was using “slander, restraint of trade, threats, coercion, and unlawful competition” to try to drive Slenderbolic out of business. Swartz also alleged that Minns had told numerous individuals that his competitor was a homosexual, and he filed a separate suit for slander.

During the ongoing dispute, Swartz found a most interesting method of keeping pace with his competitor: he hired a private detective, Neal Todd, to rifle through the trash at Minns’s office to obtain his customer mailing lists and the like. Poor Todd wasn’t quite up to such subterfuge and derring-do. His first step was to contact the maid at the building and ask her to tie a blue ribbon around the sacks of trash that belonged to Minns. The maid relayed this information to Minns, who hatched his own counterplan. He planted an expensive leather briefcase in a sack to be wrapped with the blue ribbon, and when Neal Todd took the bag the next day, he technically committed a felony theft. Minns promptly filed criminal charges against Todd and Swartz.

Minns had former district attorney Frank Briscoe, then in private practice, appointed as a “special prosecutor” on the case, a seldom-allowed procedure. The charges against Swartz were quickly dismissed, however, and after a three-day trial Neal Todd was acquitted. All the rest of the suits were eventually either dropped or settled out of court.

The ten-year legal battle with Swartz is a paradigm of the Minns style: once you sink your teeth in, don’t let go. But his associates say that Minns also has a tendency to dream. Two who have known him for twenty years between them say it is virtually impossible to converse with him; he hears only what he wants to hear and often seems to be in a kind of daze, following some vision of his own. It’s a trait that undoubtedly helped make him a millionaire, but it also made him a social eccentric and, coupled with his abundant competitiveness, made his life one protracted battle against various enemies, both real and imagined.

If overzealous competitiveness became a trademark of the Minns style, so did the peculiar way he was able to retain the friendship, respect, and even love of his foes. Many employees who left the company as a result of disagreements with Minns today count him a friend; even his ex-wife, after a bloody, contested divorce case, has little negative to say about the man.

In 1969 President’s First Lady went public. The initial stock offering at $10 a share quickly shot up to $18, but in just a few years trouble began to beset the empire. It was growing too large and unwieldy to be effectively managed by someone like Minns, who had difficulty delegating authority. Also, the Federal Trade Commission was beginning to crack down on spa advertising and contracts. Minns’s persistence had sucked a good fad dry; it was time to get out while the getting was good.

When the stock plummeted to $2 in 1970 Minns began buying it back from the shareholders—returning the company to private status. He subsequently entered into negotiations with the Health and Tennis Corporation of America, which bought fifteen of his clubs. These two moves were a brilliant stroke. Minns was able to extricate himself from the company swiftly and at a handsome profit; the stock he bought back so cheaply he sold for the equivalent of $8 to $10 a share.

The independently wealthy Minns dabbled in real estate—successfully, of course—but he seemed to turn more of his energy to personal pursuits. That, coupled with his lust for the limelight, led to his birthday feats of strength and daring each August 17.

According to newspaper accounts—notably those of Houston Post society columnist Marge Crumbaker, who became a sort of Minns glorifier—Minns performed the following feats between the ages of 35 and 49:

At 35: swam the length of Acapulco Bay in eight hours.

At 36: at a depth of 155 feet, speargunned and brought up a record red snapper.

At 37: water-skied at Lake Tahoe nonstop for eight hours, sixteen minutes.

At 38: did 2000 consecutive situps in less than five hours.

At 39: became, he claimed, the first American to dive off the cliffs at Acapulco.

At 40: dived off the cliffs again to dispel doubts about the initial exploit.

At 41: captured a three-hundred-pound sea turtle alive at a depth of more than 150 feet in Acapulco.

At 42: free-dived to a depth of 325 feet on a thirty-minute air tank off the Yucatan coast.

At 43: skied twice around enormous Lake Tahoe on a slalom ski.

At 44: killed a bull in an arena in Acapulco.

At 45: performed 3050 situps in less than three hours.

At 46: skied the length of Lake Mead in Nevada—123 miles.

At 47: skied four times around Lake Tahoe in less than nine hours.

At 48: hunted and killed a wild boar in Kenya with only a pair of throwing knives, and killed two great white sharks in the waters off Antigua, British West Indies, with a “bang stick” (an explosive-tipped lance), despite a ruptured eardrum and broken ribs.

At 49: again skied the circumference of Lake Tahoe—this time, five laps totaling almost four hundred miles in ten and a half hours.

But how much of this did Minns really do? The knife killing of the wild boar in Kenya has been questioned because Minns did not have a valid U.S. passport at the time he said the hunt took place; furthermore, despite his claims that Saga magazine had promised to help finance the trip, the magazine says it never had any deal with Minns. The 325-foot dive was also doubted by professional divers, who say that diving to that depth on so little air is physically impossible.

But by far the most controversial of Minns’s feats was his purported slaying of two great white sharks off Antigua in the spring of 1977. To begin with, great white sharks are hard to find in the Caribbean. Second, they are very difficult to kill, even with a bang stick. And third, it is hard to continue a deep dive at all, let alone fight sharks, with injuries such as broken ribs and a ruptured eardrum.

Of the photos that accompanied the event’s coverage by the wire services, one looks suspiciously like a picture in a book by Jacques Cousteau. Since the wire services freely admit that they accepted the photos from Minns with no questions asked, there is really no way to verify that they are genuine. Other people who went along on the trip say they never saw any evidence of the kills. Even the manager of the hotel where Minns stayed in Antigua disputes the story.

In the spring of 1978 Richard Minns found a town house at 312 Lichfield for $87,000 and set his mistress up in style. The move seemed perfectly natural. They were, after all, practically man and wife—Barbra had only months before miscarried a child by Dick. But for Mimi Minns, the town house was the last straw. She could apparently tolerate her husband’s sexual infidelity but not his spending money on another woman. That was their money he was using to buy the town house. She found a lawyer and finally did the one thing Richard Minns had hoped she would never do: she filed for divorce.

The divorce proceedings stretched over eighteen months and filled a large box with depositions and filings and counterfilings. The couple listed assets totaling about $10 million, including 100,000 or so shares of blue-chip stock, many pieces of prime real estate, and, of course, the holdings in President’s First Lady. Mimi Minns listed jewelry, including two brooches with a total of 84 diamonds and a bracelet with 119 diamonds. The couple also owned an extensive art collection. For the year 1977 they listed an income of $1,365,285 and expenses of $1,242,472, including $15,000 for travel and $7000 just to maintain their pool.

The divorce proceedings showed the darker side of Dick Minns. He lit into his wife the same way he had Robert Swartz. He called her a “tramp” and said they’d had to get married when she was seventeen because she was pregnant; he claimed he had married her, in part, to reform her. He denied that she was any help in building the business and said, “I don’t think she could run a health club if her life depended on it.” But Mimi Minns was more than a match for her pugnacious husband. She said his public affair with Barbra had humiliated her, especially when he had begun spending community assets on the girl. Midway through the proceedings, she alleged that Minns had threatened her with physical harm.

Barbra Piotrowski was also seeing a different Dick Minns now. He just wasn’t the same after the divorce started. He was grouchy at times; his already irregular work and rest habits became more erratic; he resorted to taking sleeping pills. With his marriage ending vituperatively and his business in liquidation, he began to take it out on Barbra.

The divorce of Richard and Mimi Minns was finally tried in the summer of 1979. Mimi was awarded about 60 per cent of the assets. Friends say Dick was crushed—not so much at losing more than half of his hard-won fortune, but at losing.

The next winter, the lovers finally decided to get married and announced as much in the Houston papers. Dick Minns very much wanted his fiancée to be a traditional wife and homemaker, but Barbra still clung to her dream of studying medicine. The disagreement caused some minor friction, but it didn’t come to a head until March 17, 1980. That morning Barbra told Dick that she was pregnant again. As Dick’s friends tell the story, she literally caught him at the door as he was rushing off to a morning business appointment; he told her to call him and they would discuss it later. According to Barbra, however, the news caused him to “become violent and threatening. He told me we were through, that he had another woman, and that he wanted me out.” In either event, Barbra decided to leave. She summoned a friend, Mary Victoria Spillers, hired a moving company, and cleaned out the town house by nightfall.

Minns must not have been happy to arrive home to a nearly empty house. Not only was all the furniture gone but some of his personal possessions were as well. He called the police. From his point of view, as recounted by close associates, the events of March 17 were quite simple: although he and Barbra had been living virtually as husband and wife, most of the items that she moved out had been purchased with his money, and taking them constituted theft. He would not press criminal charges if Barbra would return them. Barbra didn’t see the matter quite so simply: She and Dick had been living together for three years and now she was pregnant by him. Many of the things she had moved out had been purchased with his money, but he had given it to her specifically to furnish the town house. She felt she was due her rightful share of them.

On Thursday, March 20, according to an affidavit Barbra later filed with the Houston Police Department, Houston theft detective Spider Fincher, an acquaintance of Dick’s, went to the apartment that Barbra had moved into with the help of Victoria Spillers. Barbra wasn’t at home, but Fincher told neighbors that felony grand theft and arson charges would be filed against her. He said she had stolen $200,000 in merchandise from the condominium and that Houston arson investigator Mickey Brown had discovered rigged wiring in the house that implied an arson attempt. (Although Brown now confirms his role, both Fincher and his colleague Officer Charles Wells take exception to Barbra’s version but refuse to elaborate further.)

When Fincher talked to Barbra personally later that day he indicated that if she was willing to meet with him and be reasonable about the matter, he would not arrest her. If she didn’t cooperate, formal charges would be filed with the DA’s office and in all probability, he said, she would be arrested and jailed.

Barbra called Irving Weissman, a Houston defense attorney who was the husband of Dick’s sister, Janis, and a good friend of Barbra’s. Weissman said he would talk with Fincher the next day. The following morning Detective Fincher told Weissman that the theft and arson charges against Barbra were imminent. Fincher said he considered the matter not a criminal affair but a domestic one, and he urged Weissman to draw up a settlement agreement. That would resolve the matter outside the courts.

Weissman told Barbra to call Fincher. When she did, she found the detective brusque and offended that she had called her attorney rather than simply showing up at police headquarters herself. He told her that unless she did something quickly, arrest was inevitable. He also told her to call Mickey Brown about the arson charges. Brown told her he considered the arson charge a serious one, and he too urged her to make amends with Minns.

At the same time, Minns’s attorney, Harry Brochstein, contacted Weissman to arrange a meeting. The following Monday, March 24, Barbra, Weissman, Minns, and Brochstein met at Brochstein’s office. Minns’s attorney presented a typed settlement agreement and urged Barbra to sign it. The agreement said that Barbra would receive all the furniture and furnishings that she had taken, and $500 cash “in consideration of any future action I might take against him including divorce, breach of promise, and paternity.” Barbra and Weissman both felt the offer was hasty and perhaps unfair, and she refused to sign.

The same day Mickey Brown called Barbra’s father in Los Angeles and told him that his daughter was in trouble and urged Piotrowski to prevail upon Barbra to settle out of court. The same week Minns himself called Piotrowski repeatedly, alternately saying that he loved Barbra and demanding a settlement or jail.

In early April Minns asked through intermediaries to meet with Barbra privately. As she later put it, “Because I loved him and wanted to see if there was any way of working things out, I went to see Dick at Guest Quarters [a posh Galleria-area hotel where Minns was staying]. I waited for Dick outside his room until sometime past 2:30 a.m. Dick stepped off the elevator with another woman. We had some words and when Dick put his arm around the woman I became outraged. I hit him with my purse, ran downstairs and out to my car, and started to drive away. Dick stopped me. He told me he loved me and wanted me back. He asked me to spend the night with him. He hugged and kissed me.”

When they returned to the hotel the other woman was still in the lobby; Minns told Barbra he needed to speak with the woman briefly to arrange to have her taken home. “I left again and Dick came after me. This time he took my car keys. We went up to his suite. The woman was there on the phone. The three of us talked for a few minutes [after she got off the phone]. I begged Dick to give me my keys and let me go. . . . He refused. . . .There was a knock on the door. It was three policemen. Dick said, ‘There she is, you have a warrant for her arrest.’”

At the police station Fincher reiterated the deal: cooperate with Minns and you go free; don’t cooperate and we lock you up. Barbra asked to see her lawyer and remained in jail until the next morning when Weissman posted bond.

Barbra’s case was postponed several times before it went to the grand jury. In the meantime, Bob Delmonteque, a business associate of both Brochstein’s and Minns’s, contacted Weissman and Barbra’s family urging them to settle; Delmonteque even said that Minns would pay $20,000 cash plus the furniture. Even with the leverage of criminal charges against Barbra, Minns was obviously anxious to resolve the matter.

On April 18 Barbra joined Irving and Janis Weissman to celebrate Janis’s birthday. Later that evening, when Barbra returned home with her date, she noticed a group of strange men congregated near her apartment; according to her affidavit, she asked her date to drive around the block. They were followed. Barbra had her date pull up to a U-Totem so they could find out who was following them. Out of an unmarked car stepped Detective Fincher and Officer Wells. Fincher said they needed her to come with them, that they needed to inspect her apartment. Barbra asked if they had a warrant; Fincher said no, but they could get one instantly. Barbra said she wanted to call Weissman. She went into the store to the pay phone, but before she had finished dialing the number, Wells grabbed the receiver. He told her she was going with them now, whether she liked it or not.

When they arrived at her apartment, Minns, a group of his employees, and two professional movers were waiting for them. Inside, Barbra was finally allowed to contact her attorney. Fincher got on the line too. Weissman said he was on his way. Meanwhile, the detectives told Barbra they wanted to bring Minns up to the apartment to point out what had been stolen from him. Barbra refused, requesting a warrant. The detectives ignored her and brought the movers and Minns inside. Minns proceeded to claim that most everything in the apartment was his; Barbra produced receipts in her name for much of the merchandise, but the men continued to ignore her.

“My apartment was left a shambles,” Barbra later swore. “Almost everything was removed . . . everything that wasn’t, was thrown on the floor . . . I was left without even a bed to sleep in.” A few minutes after the movers had gone Barbra received a call from Victoria Spillers, who said Fincher and Wells had just gone through her apartment also. She said they were going to arrest her. And when Barbra, the Weissmans, and her date prepared to leave at about five o’clock in the morning they discovered that all four of Weissman’s tires had been slashed and the windows of the vehicles had been covered with hair spray.

Barbra filed this chronology of the events with the Internal affairs Division of the Houston Police Department, but Internal Affairs agreed with the officers’ somewhat different version. Their explanation was simple: the girl had committed theft; charges had been filed and accepted by the DA’s office. The complainant and the police had a right to take back the property as evidence. Until and unless she was cleared, she had no right to resist recovery of the property. The officers were completely exonerated.

Minns’s friends later produced affidavits from the movers claiming that Victoria Spillers had asked if they knew anyone she could get to kill Minns. They also produced affidavits from two employees of a Western wear store who claimed that Spillers had traded in an expensive belt buckle, which turned out to belong to Minns, for a gold chain and had later exchanged the chain for about $500 cash.

There was also a story going around that Barbra had done this sort of thing before, that five years earlier she had ripped off Paul Berns the same way. Berns later flatly denied the charge and revealed that he had been contacted by a Los Angeles–area private detective who told him he could “have back that five thousand dollars Barbra took” if he agreed to testify against her on the theft charges.

After Barbra was indicted by the grand jury a prosecutor asked Weissman, “Why don’t you settle this thing?” But Weissman wasn’t about to do that. Since Dick and Barbra had lived together for three years and she had been pregnant by him twice, there was a clear issue of common-law marriage and paternity. Weissman was worried about Barbra’s safety, to be sure, but he wasn’t about to be buffaloed into a settlement that was unfair to her.

He soon enough began worrying about his own safety. As Barbra moved in with the Weissmans and the theft charges continued to dangle in limbo, strange things began to happen to the tall, avuncular defense attorney. His office on Westheimer was burglarized twice; in each case nothing was taken, but the burglars went through files where Barbra Piotrowski’s personal papers and documents would have been located had Weissman not moved them a few weeks before.

Wes and Stella Piotrowski were also getting their fair share of trouble. One afternoon not long after Barbra’s arrest, Mrs. Piotrowski was working in her front yard when a tall stranger drove up, approached her, and introduced himself as a city tax appraiser. He asked if she knew the value on her home. When she said she wasn’t sure, he left. Later that afternoon, after Wes Piotrowski had come home, the man returned with two uniformed Los Angeles police officers. He introduced himself as Dudley Bell, a Houston private investigator who worked for Richard Minns. He said he had photographs that proved that the gold necklace Mrs. Piotrowski was wearing was one of the items “stolen” when Barbra moved out on Minns. He said he was in California to recover the necklace as evidence. After resisting for a while, the Piotrowskis finally handed over the necklace, which had indeed been a present from Barbra.

In the first week of May, the grand jury indicted Barbra for theft. Then Weissman resigned as Barbra’s attorney. His being Minns’s brother-in-law was only exacerbating the situation. Barbra shopped around for another lawyer, and as a result of several recommendations, decided on Dick DeGuerin, one of the rising stars of the Houston criminal defense community. Barbra later said that she was certain her phone was being tapped and that Bell was having her followed. Then one day, while she was on her way to DeGuerin’s office, her car inexplicably stopped running. When DeGuerin checked it out he found a mysterious apparatus under the hood that looked terrifyingly like a bomb. The device turned out to be part of a sophisticated radio control instrument that allowed a passenger in a trailing car to shut down the engine of Barbra’s car by merely punching a button.

Meanwhile, Barbra was desperately trying to pull her life together. She got a new apartment; she poured herself into personal pursuits: work in the Hermann Hospital Burn Unit, giving lessons at an aerobic dancing studio. She dated a little. One afternoon, while jogging in Memorial Park, she ran into an old acquaintance, Willie Rometsch, a Houston restaurateur. They chatted briefly and Rometsch asked her to drop by later for dinner. The next day Rometsch got a phone call from Minns, who related verbatim his conversation with Barbra in the park—suggesting not only that Barbra’s claims that she was being followed were correct but that she was being taped as well.

Such incidents as these began to wear on Barbra. Her nerves were frazzled from the wear and tear of worry over the criminal charges against her; she was also, most friends would later admit, still carrying a torch for Richard Minns. She had had another miscarriage. Her character also included a streak of stubbornness, and family members later said she almost made a crusade of her relationship with Dick Minns. It wasn’t just that she loved him; she wanted it to work.

Patrick Steen, 21, and Nathaniel Ivery, 26, were cruising around Southwest Houston in search of their quarry on the evening of October 20, 1980. The two drifters were not in a mood to be picky about sites for the hit. For several weeks now they had followed Barbra—watched her jog at Memorial Park, seen her go to and from classes at the University of Houston, checked out her new apartment on Landsdale. They were by now intimately familiar with the rhythm of her daily life. All that remained was for them to end it.

The task seemed especially urgent on October 20 because they had come close, very close, the night before. After making a quick pass by her apartment, they’d decided to knock on the door, just to see what would happen. Barbra refused to open the door. Ivery made up a couple of girls’ names and asked her where they lived, just to stall. “Go next door,” she said in a small voice, and Ivery said he wanted to off her right then, through the door. Steen finally talked him out of it: one thing about this murder-for-hire business, he told his partner, was that you had to be sure—which wasn’t exactly possible with a locked door in the way.

Today could be, should be the day—that is, if they could find her. Cruising by her apartment, they’d seen her bright red Firebird and decided to follow her. But a few red lights and a few turns later, they’d lost her. A week earlier they might have blown it off, called it a day, but on this Monday evening, as the mist of Houston nightfall descended on the city, Patrick Steen and Nathaniel Ivery decided that they would find her and that when they did, they would kill her.

They finally spotted the Firebird, parked to one side of the Winchell’s Donut House at Gessner and Beechnut. Inside the car was a gloomy Barbra Piotrowski. She had decided to indulge in the worst of her guilty pleasures: junk food. A couple of gooey doughnuts, then a nice ten-mile jog in Memorial Park, and maybe she would feel better. That was when she looked up and saw a strange man approaching her car, fumbling with a rumpled paper sack.

Barbra knew right away that he meant to kill her. Instinctively, she flipped on the ignition and tried to wrestle the gearshift into reverse. The man stopped short, raised his hand, and fired. The gearshift screamed into reverse and the car skidded backward; there was a second shot, then one, two more. The gunmen sped off in their Cadillac. But unfortunately for them, a police patrol car happened to be driving past the doughnut shop.

Houston police officers W. E. Hamby and D. J. Pannell must have thought they had died and gone to some special heaven for cops. Television mythology notwithstanding, the average patrolman seldom, if ever, gets the opportunity to witness a crime of any kind in progress. But here they were, just cruising around, and suddenly they found themselves watching an attempted murder.

As the two officers wove in and out of post-rush-hour traffic, trying to keep pace with the fleeing Cadillac, other police and ambulance units arrived at the scene of the shooting. Without prompting, the victim said in a wheezing voice, “My husband shot me.” And when asked her name, she mumbled, “Barbra. Barbra Mimms.”

After news of the shooting hit the papers, detectives Tom Ladd, Kenny Williamson, and M. F. Kadartzke were perhaps the only people in Houston who had no time for speculation about Richard Minns. Cops, especially homicide investigators, learn early on that rumors are cheap. Their unsavory chore was to pin down the facts of the botched murder attempt at Beechnut and Gessner. Step one was to see if Steen and Ivery would sing, and the two suspects couldn’t have been more accommodating. Ivery, who was the trigger man, said that he and Patrick Steen had been on the streets in their hometown of Riverside, California, selling drugs and passing counterfeit bills, when they were offered the opportunity to sell a hot car, which ultimately brought the two black men into contact with an older white man by the name of Robert Anderson. After some troubles with the law over the hot car, Ivery said, he and Steen once again ran into Anderson at Rocco’s Restaurant in Riverside. This time Anderson, whom they also knew as Jess, wanted them to do some arson in Colton, California. After performing that task for $100 apiece, Steen and Ivery were offered a job in Houston.

“Bob [Anderson] approached us with a deal about kidnapping a girl,” Ivery told the detectives. “He told us that he did not know the reasons that the girl was supposed to be kidnapped, but it had something to do with her possibly being pregnant and that she might cause trouble for this guy and his family. . . . He did not tell us the man’s name but did say, ‘Would you believe this is a judge?’ He said that it would be better if she was dead, but that the kidnapping would be all right. After we arrived in Houston, Bob picked out a motel somewhere on Highway 45. The next morning we went to Bob’s farm, which is located somewhere off Spring Cypress Road. . . . Bob took Pat and I to another house where we picked up the Cadillac that we were driving when we were caught. There was another white man at the house where we picked up this Cadillac; he was in his early 50’s, 5’7”, 165 pounds, short crew-cut hair. I did not meet this man and was not told what his name was.”

Ivery went on to say that Anderson provided them with a .44 pistol and certain details about the young blonde girl’s daily schedule. After spending a few days scoring some drugs, Steen and Ivery met Anderson at Memorial Park to watch the victim jogging. “We discussed the girl that was supposed to be kidnapped, only this time he said that the girl was to be killed instead. He told us that we could get $10,000 for the job. The money was supposed to be split, with Bob getting $2000 and Pat and I getting $4000 each.

“Bob told us that the man that wanted this done was a ‘Judge Dudley Smith’ and the reason that he wanted it done was because she was going to turn state’s evidence against him. After we agreed to do the job, Bob took us out to show us where the girl’s apartment was located. We had trouble finding the apartment. Bob stopped and called the guy . . . he told Bob that he would meet with him. Bob told us that the man was a big man and described him as being well over six feet tall, maybe six-three or six-four.” Ivery said he never saw “Judge Dudley Smith,” but he did see a “black over gray Cadillac” that Anderson said belonged to the judge at a Marriott Hotel.

The day of the shooting, Ivery said, “We were coming back to the apartment when we passed a red Firebird. I told Pat that looked like her car. Pat turned around and we started following her. We lost her and we had turned down this street when I spotted her car parked at the donut shop. I got out of the car and started toward her. . . . I put my hand inside the bag and pulled the trigger twice, but nothing happened. I had the other gun that I had stolen from this white dude stuck in my belt and when the .44 did not fire, I pulled the other one. I fired the gun at her four times. I knew that I had hit her because on the last shot I could see the laceration and I heard her go ‘uh.’ ”

After running routine checks, the detectives located Robert Anderson in far North Harris County, where he’d been living for a couple of months with his wife and children. Anderson offered little resistance when he was picked up for questioning on Friday, October 31.

Unfortunately, the big, beefy 46-year-old Californian with the Pancho Villa moustache was not as willing to talk as his alleged accomplices had been. In fact, he wasn’t talking at all. Worse, the physical evidence that might corroborate his participation in the hit didn’t hold up. The .44 Steen and Ivery said Anderson gave them for the murder was traced to Wyoming. Nothing in the records on it linked it to Anderson. The Cadillac was traced to the Transport Leasing Company in Rialto, California, a small town near Riverside. Anderson had worked for Transport and, the detectives discovered, had taken over sole ownership of the car when the company was sold. That tended to support Steen and Ivery’s version of the attempted hit, but with Anderson continuing to stonewall and one of the weapons out of the picture, the evidence against the Californian was questionable, perhaps unusable. The car was apparently Anderson’s, but so what? Without further supporting evidence, a defense attorney could easily argue that Steen and Ivery had merely stolen the car, or that even if Anderson had lent it to them, he knew nothing about a murder-for-hire attempt.

The detectives and the DA’s office were now in a real bind. Steen and Ivery had been firm and convincing when they implicated Anderson in the crime, but under Texas law the word of one crook isn’t enough to convict someone else. Objective corroborating evidence must support the confession. The DA’s office decided to take Anderson to the grand jury anyway. After hearing his testimony, the grand jurors refused to indict him in connection with the case. The detectives’ one slim lead had evaporated as quickly and inexplicably as it had appeared. The shooting at Beechnut and Gessner was once again a full-fledged mystery. As assistant district attorney Ted Wilson said ruefully after Robert Anderson was released, “We’re stuck with uncorroborated witness-accomplice testimony. We’re wondering where in the hell we’re going to go from here. It isn’t like TV, it isn’t simple.”

Barbra’s attorney, Dick DeGuerin, decided to take the offensive. In December, after weeks of avoiding reporters’ queries about his client and her allegations against Minns, DeGuerin went into open court—where he was representing Barbra on the theft charges Minns had filed against her months earlier—and, as he put it later, “decided to take the lid off” the speculation. DeGuerin told the court that he intended, at the appropriate time, to prove that Richard L. Minns had been behind the attempted murder of Barbra Piotrowski: “We believe the complainant in this case [Minns] is the person that hired—through intermediaries—the assassins.”

After hearing the allegations, Minns took the opportunity to respond to the rampant speculation about him for the first time. “I’m not a defendant,” he said angrily. “I’ve been told I’m not a suspect. The only crime I committed was to fall in love with a beautiful girl from California.” He subsequently sued DeGuerin and his senior partner Percy Foreman for slander.

The detectives involved in the case still gamely say the case is open, but anyone who knows anything about crime knows that with each day that passes, a case becomes more unsolvable. There are no new leads and no theories. Nothing implicates Minns or anyone else.

As for Barbra Piotrowski, DeGuerin has been forced to move her at least twice to different hospitals under different pseudonyms for fear her would-be killers had discovered her whereabouts. Recently, a fellow patient Barbra had become acquainted with left the hospital and found all four of his tires slashed.

On March 30 Patrick Steen and Nathaniel Ivery were unceremoniously tried and convicted for the attempted murder of Barbra Piotrowski. It was a spectacular anticlimax, a fitting requiem to this bizarre Big M. Since the two had confessed fully to the crime, the state’s case was short. After three days, they were each sentenced to 35 years in prison.

In the wake of the convictions, the case has predictably faded from prominence. One thing about Big M’s is that they cater to a fickle, demanding public; they must keep producing new twists of fate, new characters, and new revelations or they are quickly relegated to the status of mere statistics. For followers of Big M’s, the shooting at Beechnut and Gessner left too many unanswerable questions.

But as a love story, it lingers. Barbra Piotrowski now awakens each morning a cripple from the waist down, spends her days in endless hours of therapy and her nights in a heavily secured hospital room under an assumed name. Her friends say she wonders sometimes if some part of her doesn’t still love Richard Minns.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime

- Houston