Why all the fuss about Houston Astros second baseman Craig Biggio’s retirement?

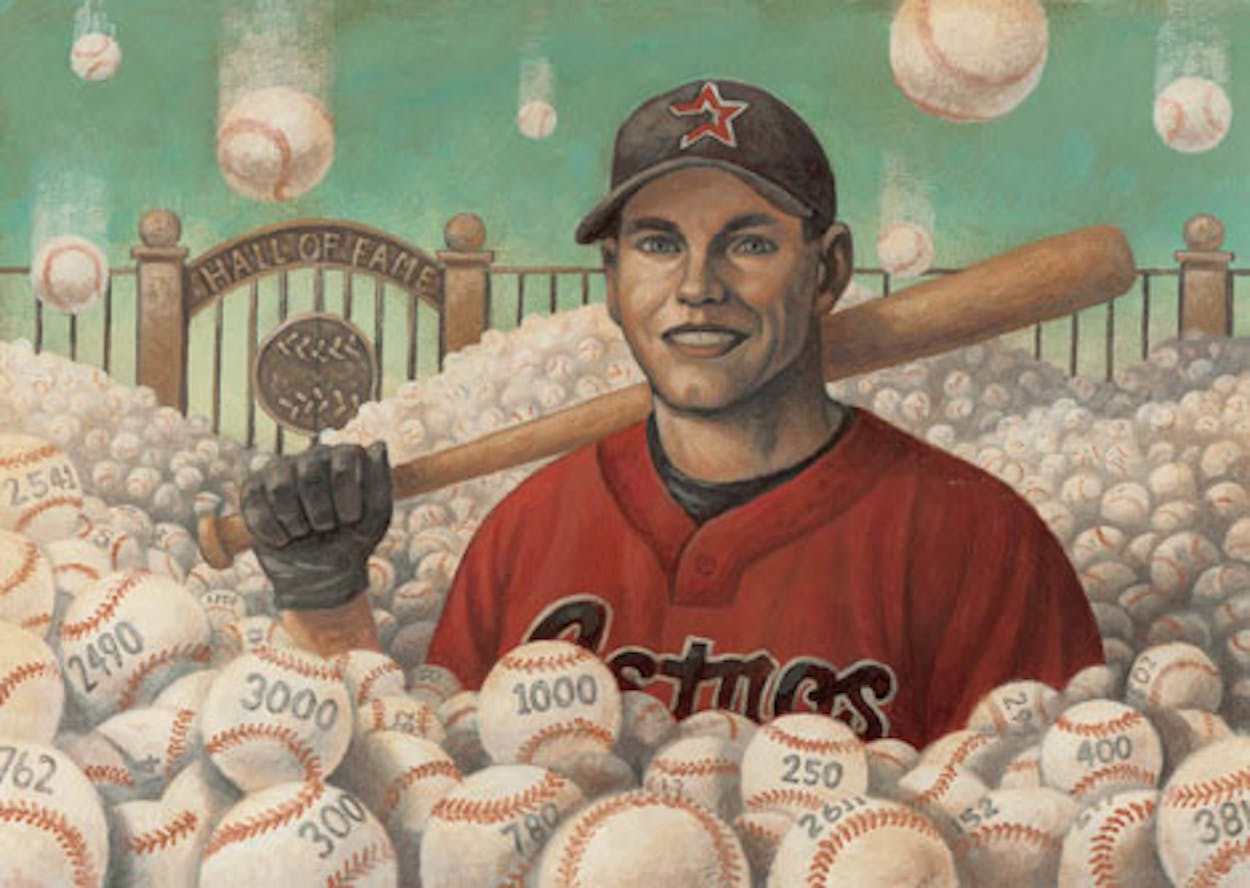

It’s not just his outstanding career—although that would be reason enough: He’s just the twenty-seventh player in major league history to get 3,000 hits and the twenty-seventh player to reach 1,000 extra-base hits; he’s the only player ever to exceed 600 doubles, 250 homers, 3,000 hits, and 400 steals; and he’s one of only two middle infielders in the history of the game—Cal Ripken Jr. is the other—to top 3,000 hits and 1,000 extra-base hits. He holds the records for the most doubles by a right-handed batter, the most home runs to lead off a game by a National Leaguer, and the most times hit by a pitch in the modern (post-1900) era. It’s also his loyalty to Houston—he played his entire career with one franchise—and his character. At a time when stars like Barry Bonds have brought shame to the game, Biggio stands out as someone who played baseball as it was meant to be played. He gave it his all, every day. When he got his 3,000th hit, he didn’t stop at first base to soak up the cheers; he tried to stretch a single into a double. He could win games with his bat, his glove, and his head. And he didn’t showboat.

But he didn’t lead the Astros to a world championship.

No, but he and his fellow Killer B, Jeff Bagwell, gave Houston something almost as important, something the city had never had before: a winning team. From 1992 to 2005, the “Lastros” (as their fans once called them) had only one losing year (2000). It was Houston’s misfortune that its mini-dynasty coincided with the Atlanta Braves’ dominance of the National League. Alas, by the time the Astros finally reached the World Series, in 2005, Biggio had begun to fade.

Will he be elected to the Hall of Fame?

He won’t be eligible until five years after he’s retired. Then he must be selected on 75 percent of the ballots cast by the baseball writers. Not to worry. He’ll be elected on the first ballot.

Was he destined for stardom from the beginning?

Seemingly. A catcher at Seton Hall University, he was the Astros’ top draft choice in 1987, the twenty-second player picked in the first round. (Ken Griffey Jr. was chosen first.) Biggio justified the Astros’ judgment a year later by becoming the first non-pitcher among the hundreds of players drafted in ’87 to be brought up to the major leagues. He became a starter in 1989 and showed such versatility (13 home runs and 21 stolen bases) that he batted leadoff, which is rare for a catcher.

Why didn’t he remain at catcher?

His defensive skills were average at best. In 1989 he threw out only 17 percent of the base runners who attempted to steal against him. Even so, he was good enough to make the National League All-Star team as a catcher in 1991. But the more important reason for moving him to a new position was that catching takes a huge toll on the legs, and Biggio’s speed was too valuable to put at risk. In 1992 the Astros moved him to second base in spring training, employing a Ping-Pong paddle in a drill to help him learn how to position his glove, and he made the All-Star team again. He is the only player ever to be named an All-Star at both positions. By 1994, Biggio had adapted so well that he won the first of four consecutive Gold Glove awards at second base.

It seems that only recently has he come to be regarded as a great player. Why was recognition slow in coming?

He was overshadowed by Bagwell for most of the fifteen years they played together. (Power hitters always get better press.) In 1997, for instance, Biggio had a career year. He scored a major-league-leading 146 runs, tying Rickey Henderson’s 1985 mark for the most scored since Ted Williams plated 150 in 1949. He drove in 81 runs (phenomenal for a leadoff hitter), socked 22 homers, stole 47 bases, and batted .309. But Bagwell, with 43 home runs and 135 RBI, finished third in the Most Valuable Player voting. Biggio finished fourth.

Does anybody think Biggio doesn’t belong in the Hall of Fame?

Jean-Jacques Taylor, of the Dallas Morning News, wrote on July 12, “I just don’t think Biggio is a great player. . . . Biggio is in the Hall of Very Very Good. . . . He’s never been a dominant player like [Hall of Famer] Ryne Sandberg was.” Perhaps Taylor’s baseball judgment can be explained by his having followed the Texas Rangers for too long. Biggio has more hits than Sandberg, has scored more runs, has driven in more runs, and has hit more home runs. He has the advantage of having played in more games, but Taylor himself identified longevity as a standard of greatness. Biggio achieved it. Sandberg didn’t.

What do the experts say?

In The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, published in 2001, the author, known as the Babe Ruth of baseball statisticians, ranked Biggio as the fifth-greatest second baseman of all time, behind Joe Morgan, Eddie Collins, Rogers Hornsby, and Jackie Robinson. That is elite company—and every one of them is in the Hall. See you in 2012.