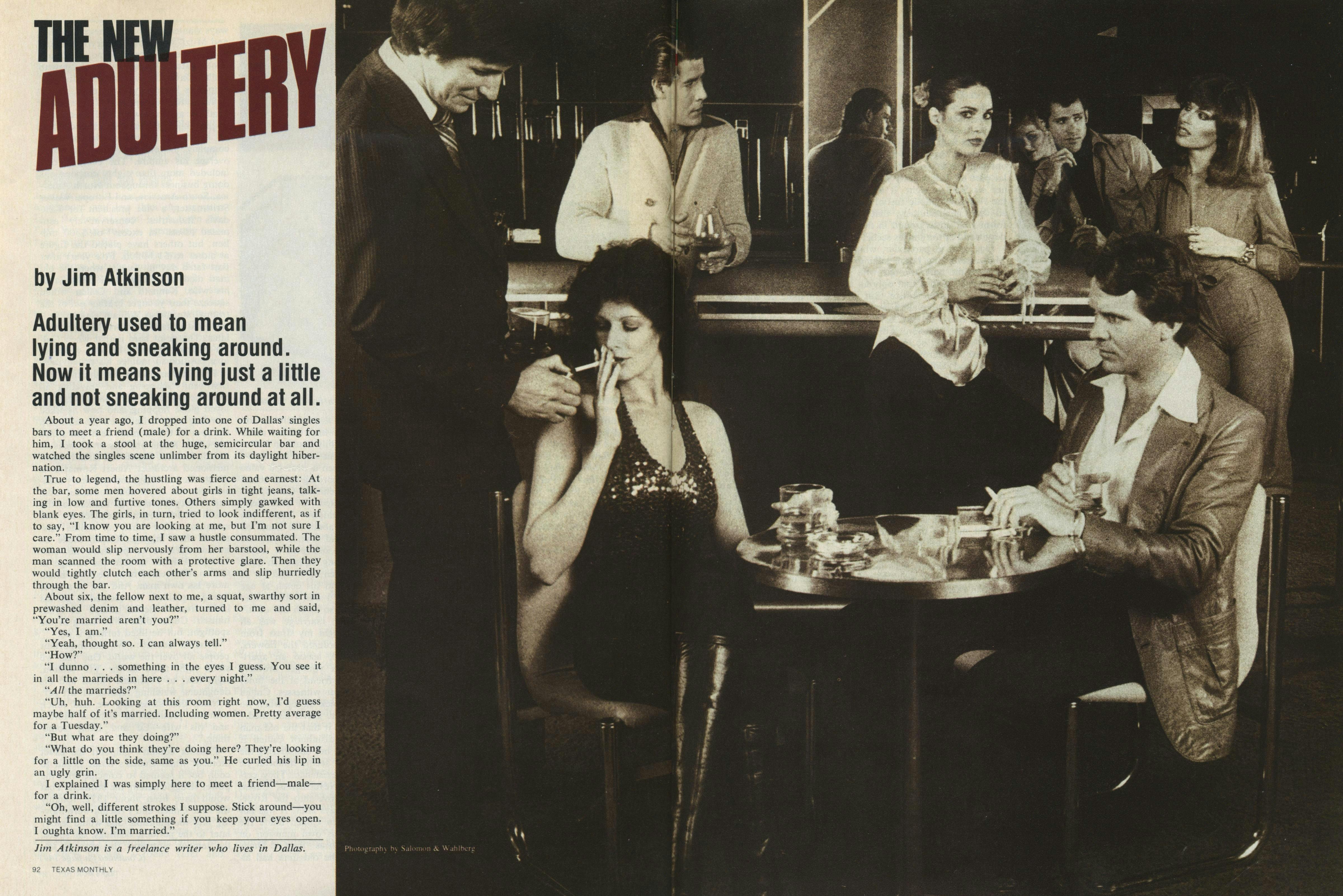

About a year ago, I dropped into one of Dallas’ singles bars to meet a friend (male) for a drink. While waiting for him, I took a stool at the huge, semicircular bar and watched the singles scene unlimber from its daylight hibernation.

True to legend, the hustling was fierce and earnest: At the bar, some men hovered about girls in tight jeans, talking in low and furtive tones. Others simply gawked with blank eyes. The girls, in turn, tried to look indifferent, as if to say, “I know you are looking at me, but I’m not sure I care.” From time to time, I saw a hustle consummated. The woman would slip nervously from her barstool, while the man scanned the room with a protective glare. Then they would tightly clutch each other’s arms and slip hurriedly through the bar.

About six, the fellow next to me, a squat, swarthy sort in prewashed denim and leather, turned to me and said, “You’re married aren’t you?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Yeah, thought so. I can always tell.”

“How?”

“I dunno . . . something in the eyes I guess. You see it in all the marrieds in here . . . every night.”

“All the marrieds?”

“Uh, huh. Looking at this room right now, I’d guess maybe half of it’s married. Including women. Pretty average for a Tuesday.”

“But what are they doing?”

“What do you think they’re doing here? They’re looking for a little on the side, same as you.” He curled his lip in an ugly grin.

I explained I was simply here to meet a friend—male—for a drink.

“Oh, well, different strokes I suppose. Stick around—you might find a little something if you keep your eyes open. I oughta know. I’m married.”

Now I know that adultery has been with us as long as marriage. But this struck me as different: The traditional quickie at the motel with the secretary was one thing; hanging around a singles bar looking for strange action was quite another. It struck me as a new adultery.

During the next several months, I spent a good deal of time in Dallas’ singles bars and discos along Northwest Highway and Greenville Avenue trying to get some fix on the marrieds who frequent them. I never failed to find them out in force. Sometimes they were more than half the people in the bar; other nights they were only a quarter or less. But always, they were there. And most were not there on a one-night drunken lark: running the singles bars was a regular part of their weekly routines, like taking the wife to dinner on Sunday night. It was this ritualism, not to mention the flagrantly public forum in which the marrieds conducted their new adultery, that led me to conclude that they formed an underground in the singles bars, the married underground of the singles scene, if you will.

One man in particular, whom we shall call the Married Man, spent long hours talking with me. He was my guide through the bars, the one who pointed out the small detail and subtle nuance that only an active participant would understand or even notice. But more than that, he was very determined to explain himself. He was glad, it seemed to me, to have found at long last a reason to air what had become his private obsession. Although he certainly made no pretenses of doing so, he spoke for everyone involved in the married underground; understanding him means understanding a good deal of the whole scene. Why is all this happening? Why should people regularly abandon brightly lighted homes for a murky bar? Why do the institutions of marriage and family seem so unsatisfactory to the married underground and at the same time so difficult to abandon completely? These larger social questions the Married Man, wrapped in his own obsession, never tried to answer. Selfishness, despair, loneliness, changing mores and social forms, loss of faith in old values and institutions, the pill, relaxation of censorship, guilt, affluence, all these have done their part in the genesis of the married underground and there are doubtless other forces working that only the perspective of time will allow us to see. For now, however, we have the perspective of a single married man.

Like most of the married underground, our Married Man sounds very normal. A youngish 33, who would pass for late twenties, if you ignore the fleshy paunch beginning to creep over his belt, nice looking, if only in a rather typical and middle-class way. Married eight years to the same woman (also nice looking in a typical and middle-class way), two kids (six and three), a $35,000-a-year income in the real estate business, a new three-bedroom, two-bath ranch-style in north Richardson. He likes to play a little tennis, hates yard work, watches a lot of TV (cops, news, football), has a drink now and then with the guys. He takes the wife to Patry’s or Arthur’s on their anniversary, enjoys road trips to Taos or the Hill Country for vacations each spring, insists on taking the kids to the State Fair each fall. In short he loves the wife, the kids, the house, and wants to grow old with them.

A very typical married man . . .

. . . except on Wednesday nights, when he shucks his matrimonial vestments, ignores the wife and the kids and the house, and joins the married underground.

The Married Man has been part of the underground for five months. Five months of Wednesday nights spent practicing the new adultery. Five months of leaving the office at precisely 4:30 each Wednesday afternoon and gunning the Caprice up Central Expressway, exiting onto Lovers Lane and pulling into the Texaco station on the corner. Five months of then going to the men’s room and inspecting his teeth for ugly remnants of lunch, tamping and retamping his full, blondy-brown hair until it is just so and then dabbing a dash of Aramis behind each ear and on each wrist. Five months of then stepping back from the mirror, heaving a long and satisfied sigh and quickly slipping the slim gold band off his ring finger and into his coat pocket.

And then he headed for the bars where the ritual was always the same: taking a stool in the shadows at the bar, ordering “the normal,” feeling the buzz of booze on an empty stomach and the headier booze of the bar’s marvelous, libido-charged ambience, which numbed him to guilt, freed him to return the sidelong glances and other seductive body argot of the girls in tight jeans. That ambience, the booze, the girls, the whole scene never failed to seduce him, consume him.

He never seemed the type—not really. But then, that is the way of the married underground. It is full of typical married men and women who never seemed the type, who had always held pretty typical, middle-class feelings about adultery.

In his case, it hadn’t been because he was a prude or old-fashioned or withdrawn. He had always felt the business of infidelity, if it must be carried on at all, ought to be carried on with some modicum of discretion. His two flings prior to joining the underground certainly had been: the deal with Cissy, the receptionist at the office, had lasted only a month and had been conducted solely behind the walls of her efficiency apartment in Oak Lawn; the interlude with Darlene, an old flame from college, had consisted of two lunches, three visits to the Rodeway Inn on Central (she had a roommate) and a quick phone conversation in which he curtly cut the whole business off. They were brief, clandestine, discreet, they bore no resemblance to prowling singles bars once a week in search of one-night action with a total stranger.

That had just happened. Like a whole other self inside him that welled up one day, suddenly, inexplicably, a slight tic in the personality that had just been waiting for a reason to surface and seize him completely.

But what reason? He knows he wants to stay married. God knows, he still loves the wife, wouldn’t know what to do without her—except, of course, on Wednesday nights. And he couldn’t imagine the awful, neurotic loneliness of the lives of so many of his divorced friends.

But he does have a vague and inarticulate feeling of wanting to be married somehow differently, a little more freely perhaps. Not that he would ever go for one of those tacky arrangements some of the couples in the married underground have. That is a kind of new morality-chic that turns him off: your night out is Tuesday, mine is Thursday. I won’t ask you any questions if you won’t ask me any.

Still, there is a distinction between love and sex, he thinks. He knows it sounds a little juvenile, but despite what all the teaching and preaching says, sex isn’t sacred. It’s just sex, a mindless pleasure that can be carried on with anyone simply for its own sake. Now love . . . love is sacred, special, he thinks, and while it definitely involves sex, it really depends on other more important, ethereal things. You can have love without sex, he thinks, and you can have sex without love.

Speaking of which, there is the problem with him and the wife in bed. That just happened too. He just lost interest in doing it—with her anyway. Some men his age, or so he’s read, begin to lose interest (or ability) almost totally. With him, it happens only with his wife.

At any rate, one thing that remains typical and middle-class about the Wednesday night business is his guilt. After five months in the underground, he still can’t shake it. It’s not quite as bad as it used to be. During those early Wednesday nights, the guilt could be all consuming, like a rippling nausea that spread through Kim, leaving him dry-lipped and clammy-palmed. Sometimes, as he sat in the shadows at the corner of the bar contemplating it with one of the girls in tight jeans, the question would fairly scream in his ears: What are you doing here?

But gradually the guilt diminished and almost wore off, if not in essence, at least in intensity. He’s not sure, but he thinks the guilt may have begun to ebb about the time he stopped calling her. You see, for the first several Wednesday nights, the call to the wife was an integral part of the Wednesday ritual. Sometimes he called her from the office before leaving, other times from the phone booth at the Texaco station. He always told the same feeble and empty lie about his just having a few drinks with the fellows after work. And she always responded with the equally feeble and empty fib about how he must try not to be too late. It seemed a silly hypocrisy now. After all, even after the second Wednesday, she knew and he knew she knew. But for some reason, they had both struggled to sustain the fragile fiction that there really wasn’t anything for her to know. It was a way they each could fool themselves, if only in a rather juvenile way. Like the perfunctory handshake of two boxers before they prepare to beat each other’s brains out, this was a seemingly meaningless gesture of civility that was somehow important, vital.

The call and the lie died abruptly one Wednesday when he boozily decided to call her from the bar instead of the office or the service station. He remembers listening vacantly to the buzz at the other end of the line and hearing her voice come on with that lilting “Hellooo!” she had, and then realizing in an instant of terror that the blare of the disco din and the shrill chirping of female laughter were clearly audible in the background, even as he was saying something about having a nice, quiet drink with the fellows. Thinking of the icy silence at the other end of the line when he said he might be a little late still sent a chill up his back.

The revelation that he was in a singles bar wasn’t any kind of shock to her. She knew that all along, probably. It was, he supposed, her being confronted with it in that way, being smacked in the face with the fact that her husband was out trying to cheat on her and calling her from the scene of the crime. Her silence had this effect: the two of them substituted the truth for lying. A tense and unspoken and no less fragile truth, to be sure, but a truth that in its perverse way, helped ease his guilt.

Nowadays, his guilt is, at most, an irritation, a distant gnawing in his viscera, a vague discomfort, like the bothersome recollection of a nightmare the morning-after. And it generally only haunts him in the early hours, before the booze and the ambience of the bars have seduced him once again, and then it haunts him again in the late hours, at two-thirty or three in the morning, when he crawls drunkenly into bed and listens to the uneven breathing of her feigned sleep. In those meditative moments before deep slumber, the question comes back to him: What were you doing there?

He still spends a lot of those Wednesday nights simply looking and being looked at. He’s gotten used to it. At first he felt, frankly, a little perverted, like a masher or a voyeur. But with each passing Wednesday, he began to notice that looking and being looked at were what most of the people were doing most of the time, particularly the married underground.

The reason for this is simple: scoring is not as important as the hunt. And looking and being looked at is the basic ritual of the hunt. It is not idle gawking, but a peculiar and particular idiom, a silent language of certain moves and gestures calculated to communicate specific messages.

This silent ritual is the principal allure of the bars for the Married Man. The score, the kill, becomes somehow incidental, as it does with any hunt. In the Married Man’s case, for example, only three Wednesdays in five months have consummated in scoring: the rest have been spent hunting, looking, and being looked at. After all, sex can be had at home, or bought over on Cedar Springs. The hunt can be found only in the bars.

The Married Man’s looking and being looked at progressed through several stages. During those early Wednesdays, he could spend hours simply watching the silent cant of the hunt. It fascinated him. It really was a language, with fixed responses for certain stimuli. A sidelong glance required at least a sidelong glance back, probably including a small smile or a wink. A crossing of the legs, or an arching of the back, required a fidget with the stir stick of the drink or a long and obvious sigh. A raising of the eyebrows required a checking of the watch or getting up to go to the restroom. A suppressed yawn required a shifting in the chair. From a panoramic vista, it could look like some grand ballet performed by a cast of hundreds.

Aside from this kind of clinical fascination, the Married Man enjoyed the tingle of anticipation in the air created by the hunt. It was aphrodisiac, that marvelous feeling of sex possible. And, for the first time in his life, he enjoyed the feeling of being surrounded by strangers. He’d never been a social type, an extrovert, but all the new faces and new voices and new laughs intrigued him. And so did the prospect that here, in these shadowy confines, one could get to know them.

One of his favorite looking games during the early Wednesdays was something he called “tag the marrieds,” a silly little exercise of identifying the married people in the crush of swinging singles, desperate divorcees, and uncertain separateds. This was more difficult than it might seem: the variety of the married underground, and its ability to blend into the smoke and shadows of the bar fabric, made detection difficult and in some cases impossible.

But the Married Man had developed a system, a set of characteristics apparently peculiar to the marrieds, which tended to give them away: (1) any man whose hair was box cut in the back, (2) any woman with no lip gloss on, (3) any man wearing Corfam wingtips, (4) any woman with short fingernails, (5) any man wearing an alligator belt, (6) any woman with her hair pulled back, (7) any man with a single vent in his coat, (8) any woman wearing panty hose in the summer, (9) any man who asks for a fresh glass with each new drink, (10) any woman who goes to the ladies’ room a lot.

He often savored the irony that a ring, the one dead giveaway of the married, was not part of his detection system. The reason for this was simple enough: no right-thinking member of the married underground would ever, ever be caught dead with his or her ring on while hunting. This was no frivolous custom, but a commonly understood matter of survival. One of the favorite bitches of the underground, in fact, was something called “ring-spook,” a perfectly good hustle turned sour when the hustlee discovered the hustler was married. This happened quite a bit, for even in the post-sexual-revolution decadence of the bars, there is a curious lingering Victorianism. More than one seemingly liberated lady has been known to utter those awful words, “But what about your wife?”

The Married Man personally knew of only one member of the married underground who did not live in mortal fear of ring-spook, a fellow named Hooter who he’d run into several times. Hooter, in fact, flagrantly brandished his wedding band when he ran the singles bars, claimed it was the “ultimate turn-on” for single and divorced women looking for what he called “a husband figure.” “When a chick sees that ring,” Hooter had said once, “it says a couple of things to her. One, there’s no risk of love interest or any of that, and two, she’s found a guy who will be pretty normal in the sack and probably won’t go for too much kinky stuff.”

But that kind of thinking was generally regarded as heresy by most of the married underground, including the Married Man. Aside from the practical aspects of ring-spook, the presence of his ring seemed to shatter the illusion that at least during those precious hours in the smoke and the shadows of the bars he was not married at all.

In time, the Married Man’s looking and being looked at became less observational and more participatory. One Wednesday he literally stalked a doe-eyed brunette with a taut dancer’s body from one singles bar to another for the entire evening. He never approached her, never uttered a single syllable to her. Instead he took a seat in the shadows, just within sight of her, and waited for her inevitable sidelong glance. He would glance back and allow a small grin. She would shift in her chair, cross and recross her legs. He would fiddle with his tie and heave a long sigh. Although it went no further, he thought it was a very warm and personal kind of communication. Sometimes, deep in the midst of his body conversations with her, he got the feeling they were the only two in the bar, that their plane of communication was singular, like the act of love itself.

As the evening progressed, she seemed to become as fascinated as he with the ongoing silent seduction. The moves and gestures grew more and more explicit until they were engaged in a kind of erotic dance. He took to taking bold and obvious glances at her firm, broad breasts, and she took to replying by arching her back into long and luxurious stretches, which thrust her nipples flush and tight against the gauze-thin fabric of her T-shirt. During one of these moves the Married Man first noticed that the hunt and its silent cant were not only sexual, but sex itself. This bothered him a little, brought back the nagging fear that his increasing involvement in the hunt was taking on perverted proportions. He knew the hunt was the essence of the bars, but he wondered a little if the others—particularly the married ones—were involved in the scene in the same sexual way he was.

He never considered approaching the doe-eyed brunette that night, nor any of the other girls he flirted with during those early Wednesdays. The approach and its inevitable banal small talk seemed to him a gross vulgarization of an otherwise lovely act of sex. The talk was always the same inane stuff:

“You come here often?”

“No, not that much.”

“Place is kind of plastic.”

“Plastic. Sure.”

“You been in Dallas long?”

“No, not that long.”

“How do you like it?”

“OK, it’s kind of dead.”

“Sure. Dead.”

It seemed to bastardize the whole business, and it scared him. Looking and being looked at were fine, even if his growing sexual involvement in them bothered him a bit; but the approach and all the small talk could only lead to it, the real thing, which, for a married man who still called his wife and still felt guilt, was going too far. At this point anyway.

But one thing leads to another. His guilt was jolted out of him one night by what he still counts as his most terrifying experience in the married underground. He had dropped by Carlos and Pepe’s on Northwest Highway about nine. C&P’s, as it was called, was the place, particularly for late-night action. He took a seat at the bar and scanned the throng searching for a pair of strange eyes to strike up a conversation with. Out of the corner of one eye, he spotted the biggest set of breasts he’d ever seen. He remembers literally bolting in his stool at first glimpse of them. He didn’t consider himself naive or anything, but he had honestly never seen breasts like that outside the pages of Penthouse. They belonged to a long-legged, sultry-mouthed fox with a fresh Farrah Fawcett cut. In spite of her body, her face bore the unmistakable hard edges of at least 35. She was standing alone—well, not precisely, because by now she was more or less surrounded by a gawking covey of men—at the large brass rail surrounding the small dance floor in the center of the room. From time to time, she scanned the room with an indifferent stare, basking in the attention of her audience.

The Married Man was by now very much an avid part of that audience, sitting motionless on his barstool, transfixed by the sway and jiggle of those immense polyester-covered cream puffs. Then it happened. He had turned away from her for just a moment to consider the humping, hootching bodies on the dance floor. He remembers thinking that dancing was one part of the silent body argot that did not appeal to him at all: Its explicit and raw sexuality repulsed him, as did the spastic, orgasmic faces of the dancers as they bumped and ground to the disco music. It was just a little too much. Being here was one thing, but putting himself on public display that way was a line he knew he could never cross.

When he turned back to her, his heart plummeted. She was now only five or six feet away, edging slowly down the dance floor railing and looking straight at him! Mouth slack, eyes glazed, she began to move in rhythm to the music, first with her hips, and then with them! Then slowly, very slowly, she began to move across the corridor between the dance floor and the bar, still moving in rhythm to the music, still gazing at him with glassy eyes.

He didn’t quite know how to react, particularly since her audience of suitors was now watching the tete-a-tete with leering fascination—so he just turned away from her as casually as he could, feeling the heat rush into his face. He remembers realizing in one white-hot instant what was about to happen. He considered slipping his glass on to the bar purposefully, checking his watch, and striding right past her. But it was too late, she was already upon him, tugging at his elbow, bumping and rubbing him with them, pleading in a husky, drunken voice, “Come on stud, let’s boogie!”

My God! he thought. I can’t say no! There isn’t time to explain! Well, maybe there is “Uh, nah, I don’t, uh . . . Oh, but there isn’t time! She’s dragging me across the corridor and we’re almost to the dance floor! We’re on it! And they just put on a new record! And she’s hootching and hunching around, and they’re bouncing and flouncing and I’m just standing here and the whole goddam bar’s watching! Oh Jesus Christ!

And: There’s no one else on the dance floor! The whole bar’s watching! And now what’s she doing! She’s wiggling up to me and bumping at my crotch! The Bump! Oh no! Why doesn’t someone else dance!

What if someone sees me! What if someone from the office walks in right now and sees me humping with this little fox on the dance floor! Oh Jesus Christ! What if . . . the wife walks in right now!

It seemed like the longest song in history. Eventually, he started moving tentatively to the music, if only to look a little less ridiculous. But it was no use. As one mindless disco chorus hammered on to another, he could feel the red surging through his face and see the leering grins and the laughing eyes in the bar shadows.

When the song finally, mercifully ended, she once again clutched at his elbow and said, “One more boogy stud, one more boogy!” He very firmly said, “No thanks, honey” and turned and walked to the men’s room, where he stayed for ten minutes. In the men’s room, he remembers looking in the mirror at his flushed and sweating face and saying to himself: “All right, sonofabitch! That is it for this singles bar business. That is it. A little flirting and a few drinks, OK. But this is ridiculous. You’re a married man.”

Then he left the bar quickly, through the shadows of its perimeter, and went straight home. Later that night, he made love to his wife for the first time in three months.

The next Wednesday, he returned.

He still doesn’t know why really. His resolve to himself in the mirror that night had been firm, nonnegotiable. But that next Wednesday he found himself falling back into the ritual, inexplicably, the way he had fallen into it in the first place. And as he took his customary seat in the shadows that afternoon at 5:30, he felt another firmer, more nonnegotiable resolve coming over him. A resolve that involved action, action without guilt.

Vicki was first. She was married too, and that had made it easier somehow. As he recalls, he first spotted her sitting alone at a table at the Pawn Shop, a rather sad-faced blonde with deep-set ice-blue eyes and broad, sensuous lips. She was dressed conservatively: tailored slacks and jacket, shirt and scarf, minimal jewelry. She looked vaguely out of place.

He remembers catching her eye and starting the ritual of the body cant with her and then suddenly becoming utterly bored with it, slipping off his stool, and walking directly over to her table. He lit a cigarette and said in a voice that was not his own: “You look like someone I could talk to.”

She looked up at him with a rather bored smile and said: “I probably am. That’s what all the guys say, anyway.” He slipped into a chair across the small cocktail table from her and puffed nervously at his cigarette. He had the distinct feeling the whole room was watching him, just like that night on the dance floor at Carlos and Pepe’s.

They sat in silence for a while, occasionally glancing at one another and smiling sheepishly. She wasn’t really pretty. He guessed her to be rather plain without makeup and outside the bar light. Still, her body was nice.

Finally she said: “You’re married too, aren’t you?”

He blushed and fidgeted with his ringless ring finger. “That obvious, huh?” he replied, his normal voice returning.

“Isn’t always, but with you it is.” She fiddled with the stir stick in her margarita. “What are you doing here?” she said abruptly.

He was flustered and managed only a weak-voiced riposte: “I dunno, what are you doing here?”

“Same thing you are,” she said, looking directly at his mouth.

“But I said I didn’t know what I was doing here.”

“I know,” she said coolly, glancing away to the bar.

He hesitated and then said softly, “I guess you do.”

He still felt a little uncomfortable, but somehow that seemed to break the ice. They began to talk more casually, more freely, until he realized he was thoroughly enjoying himself. She explained that her husband, a salesman, traveled a lot, sometimes four days out of the week year-round. She said she never planned for it to come to this, not really. She was sure her husband knew, but he didn’t seem to care, at least so far as she could tell. In fact, she said, it had seemed more or less to improve their relationship, which had been decaying rather rapidly since he had begun the heavy traveling.

“I think it relieved him in a way,” she said. “He’d been doing his own running around when he traveled, I knew that. I think maybe this evened it up. You might say we have an arrangement.

“How about your wife and you?”

“No, not really,” he said. “I just don’t call anymore, and she never says anything, if you want to call that an arrangement.”

“I would,” she said, watching the smoke trail from her cigarette up into the shadows.

After that, his memory clouds a little. He remembers she eventually said, “I’ve gotta go,” grabbed his hand, and led him out of the bar to the parking lot. “Why don’t we take my car?” she said. “I’ll bring you back to pick yours up later. It’s not far.”

She drove up Central into the cavernous recesses of north Dallas to a French-style house with a spreading oak in the front yard. Inside, she made a couple of weak Irish coffees while he put a new John Denver album on the stereo. They sat cross-legged in the den in front of the lifeless fireplace and once again were silent for several moments.

Finally she said: “You didn’t have to come. I hate myself when I’m pushy like that, but I can’t help it.” She forced a chuckle through her nose. “I’m horny.”

He laughed with her and assured her—that other voice returned—that she hadn’t forced him into it.

“But it’s your first,” she said.

“Yeah, more or less,” he replied. “What do you know about that? I’ve had two firsts in one week!”

He remembers she was ferocious and tireless in bed, something he had always heard about the married women of the underground. At one point, while they grubbed and thrashed on the bedspread, she kicked her feet up in the air wildly and yelped: “Look at us! Married and look at us!”

He recalls doing pretty well the first time, but by the third, he felt almost lifeless. “That’s all right,” she purred, as they lay in the shadows of the bedroom. “It’s not you. I never get enough.” At the door that night, he felt awkward, a little speechless. So he just said, “Uh, thanks . . . I mean, I guess I’ll call you sometime.”

She shook her head violently. “No, don’t call. I don’t want you to. You’ll see.”

Late that night, when he crawled between the sheets of his bed and heard his wife stir as he adjusted his pillow, he heard the question come to him, as it always did: What were you doing there? But somehow it seemed less bothersome that night; for the first time, he sensed that somewhere in the deepest recesses of his mind, he finally knew the answer.

He didn’t call Vicki the next day, nor ever again for that matter. Neither did he call Mariann or Janet, who came after her on successive Wednesday nights. Janet tried to call him a couple of times, desperate four-month divorcee that she was, but he always cut it off rather abruptly. He saw what Vicki meant. The hunt of the bars was a singular act, like any hunt; it could only be repeated with new prey.

Since Janet, there has been a lot of hunting, but no scores. But the Married Man doesn’t particularly care. It will happen again, those are the odds of the bar. Moreover, it is somehow not imperative any longer, not the way it was after that awful night at Carlos and Pepe’s. He has the distinct feeling he has purged something from his system and now feels free to roam and hunt the singles bars as a married man, enacting and reenacting the silent body cant of the hunt, savoring the particular act of sex it represents in and of itself. The other will happen when it happens.

And the question, that awful, nagging question that used to haunt him in the late hours has been eliminated. Only a few weeks after Janet, he happened to run into Vicki at the Pawn Shop. She greeted him with a wink and a mocking, “What are you doing here?” As he prepared to reply with an equally mocking, “Same thing you are,” the answer to the question suddenly came to him, surged to the front of his mind like the recollection of a name or place that’s been sitting on the tip of your tongue for hours.

He looked at her long and sad face and murmured, more to himself than to her, “I’m lonely.”

Sometimes he supposes that particular self-revelation ought to be enough to force him to face up to divorcing his wife. After all, adultery is one thing; knowing why you’re committing it is quite another. But he still can’t imagine life without her—not any more than he can imagine life without his weekly visitations to the bars. He has resigned himself to that paradox.

She, he supposes, has resigned herself, too. That would be the only explanation for her stoical silence about his Wednesday nights during the past five months. She obviously is more willing to live with some part of him, some part of a marriage, than without him, without any marriage at all. She, like he, would rather allow life to change her than to change her life.

He’s not really sure why that is.