It is three o’clock in the afternoon, and the price of oil is an even $13. More than two hundred bodies are jammed in tight around the crude oil trading pit at the New York Mercantile exchange. The air is thick with sweat and adrenaline and emotion. Everyone is screaming – a Babel of months and prices.

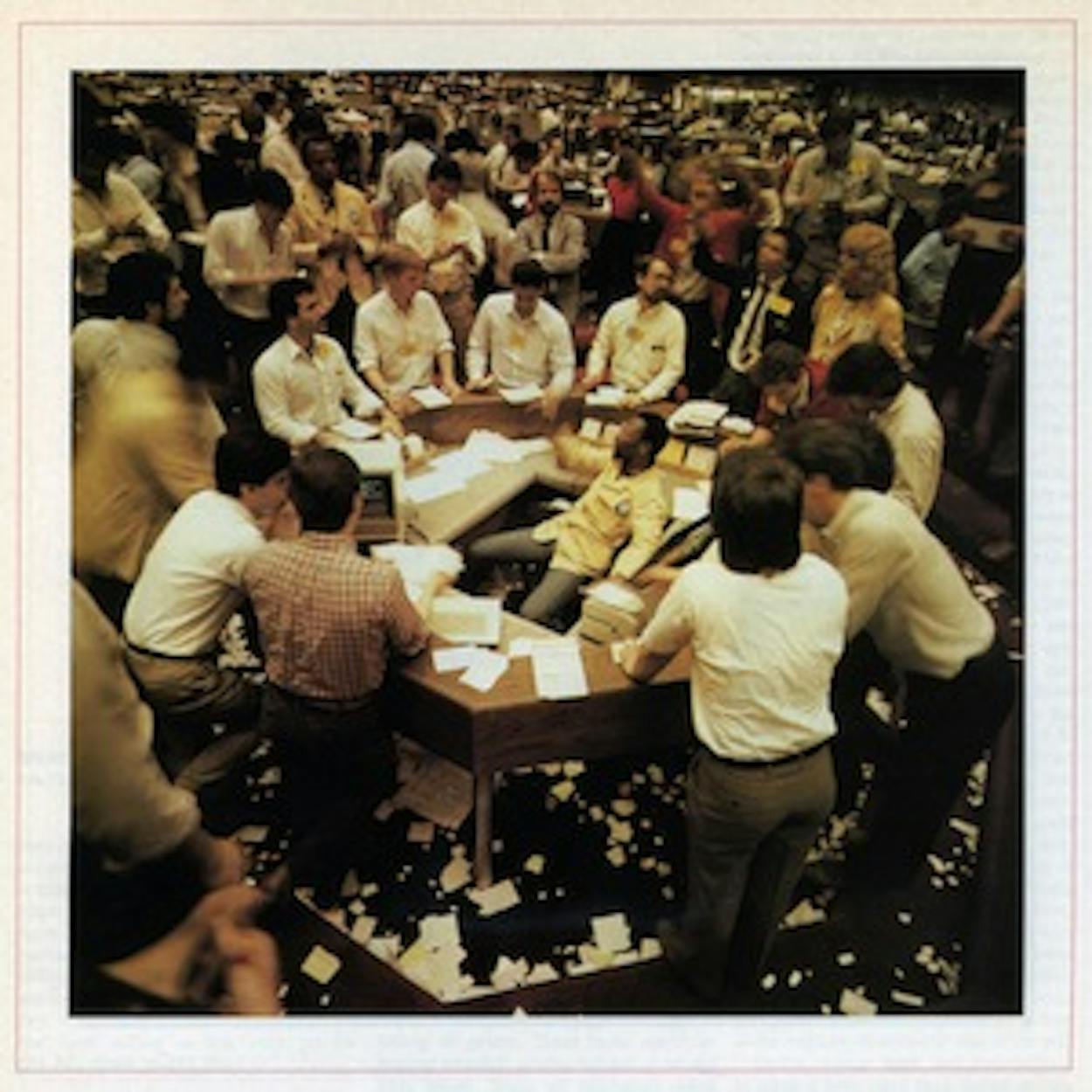

“May!” bellows a young man with a walrus moustache. “May! Ninety-eight for May!” He is jumping up and down, frantically crisscrossing his arms above his head. A tall, stocky man with thinning black hair has raised his arms at a 45-degree angle to the heavens, palms down, as if to preach a benediction. “June!” he is shouting. “June!” Next to him a lefthander is throwing imaginary darts. The shrieks represent shorthand offers to buy or sell; the exaggerated gestures are desperate efforts to win the attention of fellow traders, who are struggling to filter out every sound but a month and price they are interested in.

A blizzard of white cards, each one carrying the details of a completed sale, is floating down onto a table in the center of the crude oil pit. Around the table is a tennis net, the purpose of which is to catch wayward cards flipped into the pit by sellers. Men in gold coats flash hand signals indicating the price of each trade to a computer operator, and that price appears instantly on the tall scoreboard that dominates the wall high above the pit. On all

sides of the table, four tiers – on which the traders stand, jump, signal, and holler – rise out of the pit. The din is so loud that it is a wonder anyone can distinguish meaning from the noise.

The turbulent crude oil pit is located in a squat, featureless building in Lower Manhattan’s World Trade Center, in the shadows of the twin 110-story towers that identify the center to the world. The Mercantile Exchange shares a large octagonal chamber measuring about fifty yards across with three other exchanges. Each has its own quadrant; from the entrance, the Merc is at the upper left. Trading rings and pits occupy most of the floor space. Gold and silver are traded here, and cotton, coffee, sugar, and cocoa. But most of the action and noise are coming from the Merc’s corner of the room.

Five minutes have passed. Only five more minutes until trading closes for the day. On the board the price of oil is sinking, sinking, sinking: $12.99 … $12.95 … $12.92 … $12.90. The pit has boiled over into frenzy. On the top riser a short, thin man wearing a yarmulke leaps onto the back of a taller trader. “April!” he screams out from his perch. He descends, reappears, tries to hang in the air like Julius Erving. “A-A-A-A-pril!” The area turns into a rugby scrum. Bodies are pushing forward, pressing backward, piling on. At 3:10 the bell rings. Bodies disengage. The market is through for the day. Oil, which just four months earlier had been selling at this very pit for $31.82, closes at $12.80.

On the day that oil fell through the $13 level at the Merc, another session on oil prices took place half a world away in Geneva. It was the March meeting of OPEC, and its stated purpose was to reassert dominance over the price of oil. Not so long ago the fate of the world economy was dictated by the men in that room. They controlled the most important resource in the world, and for years its price reflected their collective whim. But the business of oil has changed. The crude oil pit at the Merc sets the price of oil today, and the people who set it are not a handful of oil-wise sheiks but a scraggly-looking bunch of kids whose median age is 26 and whose understanding of the petroleum business barely exceeds an awareness that Wesson oil isn’t sold at filling stations.

How the Merc works, why it has become the center of the oil world, and most of all, what it means for Texas are the basic issues in understanding not only the price collapse of the last four months but also what is likely to happen next. If only we had understood the Merc a year ago, everything might be different today. The State of Texas could have guarded against falling oil prices. Texas banks could be posting windfall profits instead of record loan losses. Texas oil producers could have fat bankrolls to help them outlast the price slide. Just ask Mesa Petroleum’s T. Boone Pickens. In the Merc’s most celebrated deal, Pickens sold the equivalent of Mesa’s entire 1986 production in advance – for the then-prevailing price of around $26.50 a barrel. That foresight earned Mesa $30 million.

What Pickens did, anybody in Texas could have done, regardless of whether he actually owned any oil to sell. The Merc is a futures market. It deals in contracts – paper oil, not real oil, or, as the players in the game like to say, “dry barrels” instead of “wet barrels.” All you have to do is pick up the telephone, call a broker, and place an order to sell, say, three thousand barrels of oil in September 1986 at the latest price for September deals on the Merc’s huge board. At that moment, you are legally obligated to deliver real oil on September 1. To avoid this unpleasant situation, you call your broker sometime later – it could be anything from minutes to months-and place an order for three thousand barrels, again at the latest Merc price. The barrels cancel out, and what is left is money. If the price of September crude has fallen, say, a dollar a barrel since the first call, you have just made $3000. Change a few decimal places three million barrels and $10 – and you have the Pickens deal. But change the drop in price to an equivalent increase and you lose the $3000. Or the $30 million.

Such swings contribute to the popular image of the commodities market as the Las Vegas of the financial world, a place where high rollers play craps with crops instead of dice. Indeed, the pace and atmosphere of the crude oil pit are exactly those of the craps table. But there are at least two fundamental differences between the commodities market and the casino.

Commodities exchanges like the Merc exist to provide industry with a place to play safe. Gambling is secondary. Commodities are at the mercy of nature and politics. When there is a capsid fly epidemic in Ghana, the cacao trees die. When the shah falls in Iran, six million barrels of oil a day disappear from the market. The futures market is a place to layoff those risks by locking onto a price in advance just as Boone Pickens did. That’s where the gamblers come in: someone is always willing to bet on the capsid fly. But gamblers don’t sustain the market; industry does. The second difference is that at a commodities exchange the house is neither player nor banker. The Merc, like all exchanges but unlike all casinos, is nonprofit. It charges fees for membership and for each transaction. But it is indifferent to the price of oil. Whenever the price changes, someone in the pit makes money at the expense of someone else in the pit.

Cotton, wheat, beef, and pork bellies, to name a few, have been traded in this fashion for many decades. But part of the mystique of oil has been the consensus that it was different from other commodities. Long before OPEC flexed its muscles, the price of oil ceased to be set by a free market. The cheap cost of producing oil compared with its intrinsic value to society meant that somebody, be it John D. Rockefeller or a cartel, would always rise up to control prices in self-defense against boom-and-bust cycles. But today, thanks to the Merc, oil is traded just like cotton.

And that, for many Texans in the oil business, is exactly the problem. A hundred years ago, when cotton was Texas’ most important product, the national Populist movement was born on the western edge of the Hill Country, a land where a farmer’s best efforts could coax maybe half a bale an acre from thin, overworked soil. Unable to make ends meet, the farmer blamed his problems on anonymous men in New York – brokers, speculators, railroad corporations-who reaped unconscionable profits but wouldn’t give the farmer a fair price. Today you can hear much the same story from oilmen like Michel Halbouty of Houston: anonymous men in New York-brokers, speculators, airline corporations-are driving down the price of oil on the Merc. At the Merc you hear quite a different tale: the Merc is merely a market . . . it cannot control prices . . . it can only reflect supply and demand . . . the oilmen want to shoot the messenger. But to Halbouty, the Merc is nothing less than “a tragedy for Texas and the country.”

It’s been sixteen years since Art Smith graduated from Texas A&M, but there’s still enough Aggie in him that he went to Dallas last New Year’s Day to cheer on his old school in the Cotton Bowl. And there’s still enough Texan in him that as soon as he made a little money trading energy futures at the Merc, he bought a ranch near his hometown of Rogers, southeast of Temple.

“I’ve got a pecan orchard,” Smith says. “No cattle. But with cattle prices the way they are, I’ll probably buy some before long. I wish I could spend more time there. But I can’t take time off because I lose contact with the market.”

Art Smith is a professional speculator. In the jargon of commodities trading he is known as a local. It is not a trade one learns in college, nor for that matter can anyone walk in off the street and practice it. To become a local today, one must pass the Merc’s training course and then buy a seat on the exchange, currently selling for more than $80,000. ”The floor is my office,” Smith says. “I get here at eight-thirty in the morning, before trading starts. I’ll look and see what other markets are doing, like gold and currencies. Energy is tied in with them. Then l’II review the position I’m holding. There’s no time to stop and think once the bell rings.”

Before the Merc opened its gasoline futures market in 1981, Smith was an economist for the Chicago Board of Trade (he has a Ph.D. from A&M in agricultural economics), working to get the exchange into energy futures. He quit his job, moved to New York, and soon began trading. At first he was strictly a broker, using other people’s money, operating as the in-house trader for a Chicago commodities firm and later for an oil company. Then he started trading for himself in joint ventures. About a year ago he began playing entirely with his own capital.

Smith prefers to trade spreads – the difference in value between a barrel of crude and a barrel of refined product, such as heating oil or gasoline. He buys one and sells the other simultaneously, after scanning the long columns of numbers on the board, looking for something that is overvalued or undervalued at a particular moment. In early March, Smith bought April product and sold crude at a differential of $4.15. By mid-March, a barrel of April product was bringing $6.10 more than a barrel of crude. That’s a profit of $1.95 a barrel, $1950 for the minimum 1000-barrel transaction. Buying on margin, Smith had 50,000 barrels’ worth of the action. And that’s just one spread; at the time, Smith was investing in seven hundred different spreads.

At 36 he is an old man by the standards of the pit. Above his right eye, his hairline is in retreat. His clothes are another sign of age. The young traders seldom venture beyond the minimal requirements of the Merc’s dress code (no sneakers, jeans, shorts, or shirts without collars).

But Smith leans toward dress shirts with conservative pinstripes; he has even been known to wear ties. At five-foot-seven, he makes up for his short stature with one of the most booming voices on the floor.

“It gets very physical in there,” Smith says. “Someone doing a lot of trading will push in front of a low-volume trader. I’ll push a five-lot trader out of the way.” There are few short men in the pit, and perhaps one woman in a hundred traders. Stamina matters as much as size. Like most locals, Smith starts trading with the opening bell and doesn’t quit until closing. No lunch break. Five and a half hours of constant strain on the vocal cords. The Merc has brought in an opera singer to instruct traders on how to use their diaphragms to project their voices. Even so, some have to have their vocal cords scraped every six months.

The locals give the commodities markets most of their color. Every trader knows the story of Richard Dennis, the Chicago local who made $200 million in ten years. The frenzy at the close of trading is attributable to locals, most of whom want to cancel out all their contracts, even if it means taking a loss, just to avoid exposure to an overnight catastrophe that could ruin them. Once, at the Merc’s previous headquarters a small fire broke out near the end of the trading day, filling the trading area with smoke and shorting out all but a single emergency light, but five locals refused to evacuate until they had liquidated their positions.

But locals aren’t the only players in the game. About half the population of the pit are brokers executing buy and sell orders, most of these from companies looking for insurance against changing prices. This is known as hedging. It can be practiced by anyone who stands to lose if the price of oil gets out of control – producers, refiners, even airlines purchasing jet fuel. Take the case of a producer who expects to pump 100,000 barrels in July . Let’s say that today a refinery is paying him $12 a barrel or $1.2 million a month. But what if oil goes down to $10 in July? He stands to lose $200,000. He can protect himself by selling oil on the futures market today-before it falls some more. So he sells 100,000 barrels at the going price for August crude futures, $11 a barrel. He pockets, for the moment, $1.1 million.

Now it is July . Sure enough, oil has fallen to $10, and the refinery pays him $200,000 less than he had hoped. But oil futures are falling too. August crude has also dropped $2 and is now down to $9. The producer cancels out his future position by buying back 100,000 barrels. This costs him just $900,000. Presto! He’s made $200,000 in the futures market to compensate for the $200,000 loss in the casb market. (Of course, by protecting himself against a loss, a producer also forgoes the opportunity for gain. Had the price of oil gone up, then our producer’s windfall would have been offset by a loss in the futures market.)

The example is known as a perfect hedge. The money came out exactly even. In the real world, actual cash prices and Merc futures are not in perfect harmony, so hedging reduces price risk rather than eliminates it. Or, to put it another way, there is money to be made in hedging as well as in speculating.

Over the long run, the hedgers, who represent the smart money, outperform the locals. But the locals are are essential to the market. They assume the risks that the hedgers don’t want. When the whole world thinks that oil is going down and hedgers are selling crude futures before they get any lower, somebody has to buy or the market will come to a halt. “We are the grease that makes the market run,” says Art Smith. “There’s a saying that a local is someone who buys something he doesn’t want and sells something he doesn’t have.”

Why would anyone want to buy crude for $12 when it’s headed for $10? Because it doesn’t get to $10 in a straight line. At 10:47 a.m. on March 19, April crude was selling for $14.02. An hour later it had dropped a penny. But in between it had dipped as low as $13.95, risen to $14, and dropped again to $13.95. By buying and selling at the right moment, a local could have made a nickel a barrel the first time, six cents a barrel the second. Multiply that by, say, 10,000 barrels, and you have a fast $1100. There were dozens, maybe hundreds, of tiny swings that day, even though oil fell all the way to $13.25 before trading was over. And a local is in and out of the market dozens, maybe hundreds, of times a day, looking for the swells and dips on the long downhill run.

“You can feel which way the market is going,” says Smith. “You can feel it in your bones. You get a knack for it. If you don’t, you don’t last very long.” Many locals don’t. A third are gone within a year. Some can’t handle the atmosphere; others “blow out” -lose their capital, which must be a minimum of $25,000.

Instinct is the local’s best equalizer against the smart money. A local can never match the industry insiders in knowledge; most don’t even try. “Some of the best traders on the floor have just a high school education,” says Smith. “All you need i to hone the skills by which you feel the market. We had a saying back in Chicago: ‘You can take a good local out of soybeans and put him in pork bellies, and he’ll be trading in ten minutes.’”

Art Smith doesn’t study Oil and Gas Journal or Platt’s Oilgram. He doesn’t keep up with the rig count. “I don’t read anything. I don’t talk to anybody . I don’t want to get opinions. Opinions can cost you a lot of money. I don’t mind going against the trend. Oil people always overdo everything.”

Do not refer to the Merc as the Merc at the Merc. In keeping with its newly won status as the fastest-growing commodities market in America, its executives have deep-sixed the exchange’s old nickname and decreed that it shall henceforth be known as NYMEX, pronounced to rhyme with “Timex.”

There’s a reason why the Merc wanted to change its image. Before the exchange got into energy futures seven years ago, it was in trouble. It lacked things to trade and people to trade them. Its primary offerings were two minor metals and Maine potatoes, not exactly the hottest item on the boards. Then in 1976 occurred every local’s nightmare: the shorts – that is, sellers of futures contracts – in potatoes took a terrible beating. They ran out of time to buy the same amount of futures as they had sold, and so they had to deliver real potatoes – which, being speculators, they did not have. Then they couldn’t find enough potatoes to deliver. There was a scandal, and federal regulators threatened to shut the Merc down.

“I wish I could tell you I had a dream.” Michel Marks, chairman of the Merc and the man credited with its resurrection, is sitting in a small conference room away from the pandemonium of the floor, reflecting on the watershed decision to enter the energy futures market. “But the truth is that we got into oil because we had nothing else left to trade.”

Marks was a 26-year-old potato local when the scandal occurred. With locals deserting the sinking ship to deal in gold, Marks and other young traders organized a successful revolt against the older members of the exchange. Marks was elected vice chairman. One month later the chairman had a heart attack, and Marks found himself in charge. He knew that federal regulators would never give the necessary approval for the Mere to add a new commodity . But back in 1973 the Merc had tried heating oil futures. They hadn’t caught on and were quickly shelved, but at least they could be restarted without going through a hostile agency.

Marks is short, slender, and calm, three characteristics alien to the chaos of the crude oil pit. “I wouldn’t even try to go in that ring,” he says. “You need a crowbar to get in there. The faster the prices move, the faster everyone has to move. It’s easy to panic. I haven’t seen a market in New York like that since gold.”

But in the early days of energy futures the pace was languid. When heating oil trading reopened in November 1978 only two traders showed up. Often as few as 10,000 barrels were traded in an entire day. When the first major deal was agreed on, for 500,000 barrels, the handful of traders in the ring broke into applause.

“It was real tough the first four years,” Marks recalls. “The major oil companies wouldn’t use us to hedge. The brokerage houses wouldn’t even talk to us. So we went to the wholesalers. In 1979, heating oil delivered in New York harbor was priced by the oil companies at $l.05 a gallon.

You could buy heating oil on the spot market for 85 cents, but wholesalers were afraid to buy on the spot market. The oil companies told them, ‘Buy a hundred per cent of your needs from us or we’ll cut you off.’ We told the wholesalers ‘Buy your barrels on the futures market for 85 cents, and take delivery.’ They did, and small forced the majors to be competitive with spot prices. That was the first time the majors heard of the Merc.”

Today only one Merc trade in a hundred results in actual delivery of wet barrels. But the option of delivery is fundamental to the Merc’s role as the world price-setter. If a seller’s asking price for crude decided is too far out of line with the Merc price, he can’t compete, because a buyer can always use futures contracts to acquire actual wet barrels, just as the heating oil dealers did in 1979. The single prerequisite for the Merc to set the world price is that crude must be easily obtainable in the event delivery is necessary. When the supply of oil was tight in the seventies, OPEC set the price. When the supply of oil is ample in the eighties, the Merc sets the price.

Marks has seen the trading profession change almost as much as the Merc has. “Twelve years ago there were very few college graduates in the ring. You came in through your family . Your father or grandfather traded.” (Marks is on the cusp: he is a Princeton graduate, but he learned potato trading from his father, a wholesaler.) “You started as a runner taking phone messages from a phone clerk to a broker, then you became a phone clerk, then a broker, then finally a trader. Today people start out as traders.”

Inflation changed the trading business. The price of gold and silver soared. The lure of the quick score brought in new locals and broke the old pattern of apprenticeships. Locals dreamed of driving the market the way the Hunt brothers drove silver. Then the silver market collapsed, the Hunts took a huge bath, and the psychology of all commodities markets changed. “Silver was the 1929 crash of the commodities market,” says Marks. “Today the market is more professional. You don’t hear much talk about driving the market anymore.”

In 1981 the Merc added gasoline, and then, in 1983, West Texas intermediate crude. The crude oil pit was slow to catch on. The oil world couldn’t foresee that it was rushing into a fire storm of price risk. Not until last year did crude surpass heating oil as the Merc’s most-traded commodity. Now there’s no contest. On this day in March, as the price of crude tumbled through $13, a record 49 million barrels were traded on the Merc, smashing the previous day’s record of 42 million. Heating oil and gasoline together accounted for just 20 million barrels. As for potatoes, the Merc’s old standby, far more crude oil contracts are traded in a single day than all the potato contracts consummated in 1985.

The last time that there was a free market for oil was in 1930, when the East Texas oil field came in. The field was the biggest in the world at the time. Independents beat the major oil companies to many leases. Dozens of small refineries were thrown up to process the flood of oil. The majors couldn’t sustain the price; there were too many players that didn’t control. The price began to fall. The more it fell, the more oil everybody tried to produce to keep the money rolling in. When the price fell to ten cents a barrel, the Texas Railroad Commission decided to act. It imposed limits on production known as prorationing. The state reason was conservation – overproduction could endanger the pressure in the reservoir and destroy the field – but the effect was to reduce supply and restore higher prices. There was a lot of cheating at first, but in time the commission’s rule stuck. For the next forty years, the railroad commission effectively set the world price of oil by tailoring supply to match oil companies’ estimates of demand.

The story of the East Texas field is in some ways the story of what is happening in the oil industry today. The railroad commission was replaced by OPEC as the arbiter of prices in 1973, after Texas ran out of surplus oil to keep up with burgeoning demand. OPEC enforced its prices by limiting production, just as long as supplies remained tight, OPEC was able to insist on long-term contracts for its oil. But in 1979, even as OPEC was raising prices again, demand for oil began to decline as conservation took effect. Moreover, high prices had brought new players into the game: the North Sea, Malaysia, Mexico, Alaska. By 1981 the energy crisis was over; the oil glut was on its way. Stuck with surplus oil, OPEC countries couldn’t sell it through long-term contracts, so they dumped it on the spot market – but because it was surplus, the price was lower. The spot market increased its share of oil transactions, from 8 per cent in the late seventies to more than 20 per cent in the early eighties. The price of oil began to fall. The East Texas cycle had begun: the more the price fell, the more oil everybody pumped; the more they pumped, the more the price fell.

Right in the middle of all this, the Merc began trading crude oil futures in 1983. For the first time ever, the value of crude oil as reckoned by people in the marketplace was available to anyone in the world with a computer terminal. OPEC was confronted by a rival pricing body – but the difference was that the Merc set prices without controlling them.

OPEC tried to reassert its control over prices by cutting back its production to fit demand. All that this achieved was a loss of market share: from 49.6 per cent of the free world’s oil in 1978 to 29.6 per cent in early 1985. OPEC members started to cheat on their production quotas; after all, two of them, Iran and Iraq, were fighting a war against each other and needed oil money to pay for it. Last summer the Saudis tried to play railroad commission single-handedly, reducing their production quota at the urging of other OPEC members, who then showed their gratitude by increasing their own production and taking away the Saudis’ market share.

That’s the situation as it stood last November, just before the free-fall began. The price of oil on the Merc had fluctuated from a high of around $32 to a low of around $27. And then the Saudis got smart. They figured out that the new rules of the oil game are to use the Merc, not to fight it: the way to influence oil prices today is to send a message by way of the crude oil pit. And the message the Saudis sent to rival producing nations was, we’re number one.

The Saudis abandoned their lonely role as railroad commission and went back to their old production quota of 4.3 million barrels a day, dumping 2 million barrels a day on an already glutted market. To be sure someone would buy those 2 million barrels, the Saudis gave up attempting to control the price. They entered into a new kind of oil deal known as a netback agreement, a fancy name for a simple concept. The price that the Saudis receive for their oil is the value of the refined product from each barrel, minus average refining and transportation costs. In effect, this ensures big refiners a profit-their costs are below the industry average-no matter what the price of product turns out to be. Meanwhile, the Saudis have accomplished three things. They have regained their market share, they have punished OPEC cheaters by driving down the price on the Merc, and they have made their point that they still have more influence over supply and demand – and thus, the Mere’s price – than any other producer.

The daily surplus of those 2 million extra barrels of Saudi crude explains why oil fell $20 in four months. What’s happening to all that oil? For the moment, it’s going into inventory. One day oil prices will go up again, and all that cheap oil will make somebody some nifty profits. But storage capacity is not unlimited, and overproduction can’t go on forever. Some day – sooner rather than later – one of three things must happen: (1) the Saudis must cut back unilaterally, (2) OPEC, perhaps joined by some other producing nations, will have to reach an agreement on limiting production that will stick, or (3) the Merc will do it for them. The price of oil will reflect the oversupply and sink so low that somebody can no longer afford to produce it. And that somebody is … Texas.

In a few hours Charles Maxwell will be on ABC’s Nightline, explaining the oil price decline to America. At this moment, however, Maxwell is eating yogurt mixed with cereal in his cluttered office a block from the Merc. Tall, silver-haired, and soft-spoken, wearing a gray pinstriped suit, Maxwell is the personification of a Wall Street Wise Man – which, as senior energy strategist for the securities and investments firm of Cyrus J. Lawrence, is exactly what he is. He has the additional credential of having been right. Not long after oil prices started their slide in November, Maxwell issued a clarion call that this was the big one. When oil was still above $20 at the Merc, he predicted that it would fall at least to $14.

“People kept talking about floors for oil prices: $22, $20, $18. It reminded me of when copper fell from $1.40 a pound,” Maxwell says. “Analysts said it couldn’t fall below 85 cents because that’s the American cost of production, and we produce thirty per cent of the world’s copper.

Well, copper went through 85 cents like a cannonball through tissue paper and never got back. I don’t see oil quickly righting itself either.”

Maxwell doesn’t foresee the Saudis changing their policy. “It would ruin their credibility and make them a doormat for OPEC in the future,” he says. “They’re doing this to discipline OPEC.” Nor, he says, is OPEC likely to arrive at an agreement everyone will honor. “OPEC could not agree when the price was $26 a barrel. The financial pressures are greater today than they were then. Only the hard-liners – Libya, Algeria, and Iran – are prepared to sharply cut production. Everybody else wants higher quotas or none at all. That would leave prices where they are now.”

So Texas loses. The U.S. is the highest cost producer, and when the supply exceeds demand, the highest-cost producer stops producing. It has happened in steel, in chips, and now in oil. “At $12, you shut in enough production to balance supply and demand,” Maxwell says. “The U.S. will have to shut in one million barrels if the price stays at $12 for very long, much of that in Texas and Louisiana.” If oilmen think $12 is a catastrophe, what will they think of $0?

About the only good news in Maxwell’s gloomy scenario is that he thinks $12 is the theoretical bottom of the price cycle. Oil can temporarily go lower on the Merc (it already has), because not every marginal producer will shut in at $12 but the lower it gets, the more wells wiIl shut in, and the price will rebound to $12. Until demand increases or supply decreases, it won’t go much higher. Maxwell doesn’t expect to see $20 on the Merc for at least two years.

“This is the killer for Texas,” he says. “It will kill Texas school revenues the management of small oil companies; oil company earnings; it will kill the drilling busIness a lot worse than people think.

“There’s no ha-ha-ha in this. I personally have a lot of money invested in oil wells. I’m not short the oils.”

The highway from Big Spring to Andrews and on to the New Mexico border passes through a hundred miles of some of the bleakest terrain in Texas. There are no hills, no rivers, no trees, few crossroads, and only one town. It is hard to think of this empty land, so far from the World Trade Center in every way, as tied by an umbilical cord to the chaos of the crude oil pit at the Merc. But this is an oil highway. Pump jacks outnumber cattle here. The oil that they pull from the ground is West Texas intermediate crude, the benchmark crude traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange.

Not too many years ago this route shook with the rumble of oil-field service trucks. Caliche roads, newly scraped out of the desert grasses, penetrated the back country on their way to drilling rigs. But on a day in early April, not one service truck appears along the entire length of the drive. And while there are plenty of rigs in the fields, they are not the tall rigs with raised platforms that are used for drilling new wells but the shorter work-over rigs. All through the northern Permian Basin, wells are being plugged. Twelve-dollar oil is taking its toll.

Would things be any different out here if the Mere had stuck to potatoes? The oil patch argument that it would runs something like this: There was an oil glut for three years, and the spot market price fell only around $7 to $8 a barrel in all that time. The spot market, because it was secretive and a closed shop for the oil business, didn’t have the unstabilizing effect on prices that the Merc’s screen – and the headlines they generate – has. Up to 65 per cent of the free world’s oil was trading on the spot market late last year, and yet prices held up. It was only when the speculators began buying and selling at prices real oilmen would never have considered that the price nosedived.

There is a little truth in all this, if only a little. The reason behind $12 oil is a long history of global events leading to the oil glut and culminating in the Saudis’ decision to open the pumps. But the reason that the Saudis’ strategy of overproduction has been so effective has a lot to do with the Merc. Without the Merc, spot market prices would probably be higher today – on the way down but higher. The crude oil pit reacts instantaneously; the pot market does not.

Where the Merc has had its greatest impact is not on prices but on the oil business itself. In the old days it was easy to run an oil company. You produced your own oil, you piped it in your own pipeline to your own refinery, you hauled it to your own gas stations in your own truck. The big companies were self-hedged. Today and for the foreseeable future, they are at the mercy of price fluctuations, unless they use the Merc. One oil company executive recently told the New York Times, “This year the most important product for the oil majors will be risk management.” In the years to come, oil companies are more likely to be run by financial types than by engineers.

Come fall, the Merc will change the oil game again by offering crude oil options. An option is a form of insurance policy. Say that prices go up and you buy an option to sell oil six months from now at $20. If the price falls again, you exercise the option and sell for $20 a barrel. The effect is the same as a futures contract. But if the price rises, let’s dream, to $25, you let the option lapse and take the $5 gain less a fee for canceling the option. Options are easier to understand and less risky than pure futures; consequently, they will be far more widely used. A bank, for example, can protect its oil loans by requiring a borrower to take out options to sell oil at a price that will enable him to pay off the loan.

Maybe none of this will be necessary. Maybe some miracle will occur, and OPEC will work everything out, or Iran and Iraq will make peace, or Britain will cut back in the North Sea, or something else will happen to raise prices. It’s a strange, strange moment for Texas. All through the seventies Texas oilmen told anyone who would listen that the way to beat OPEC was to deregulate oil, let the price go up, and the market would take over. And they were right. But in the meantime they forgot their own message and bought the myth of $50 oil and $9 gas, and so did the banks and the drilling companies and the real estate developers, and now that oilmen have the free market they always wanted, it’s killing them. Meanwhile, with prices volatile and risk everywhere, the Merc is booming.

“We thrive on wars, plagues, and famines,” says Art Smith, the Aggie trader. “When there’s human misery, we do very well.”