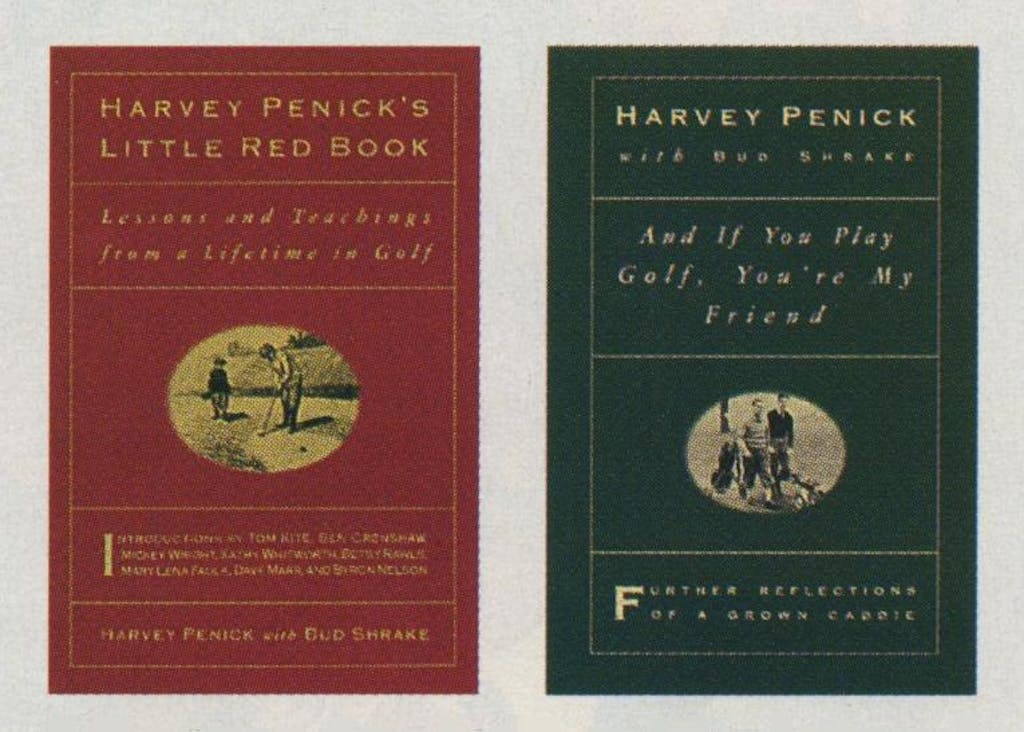

Disciples of gold who regard Harvey Penick’s Little Red Book, as a revelation on par with the tablets of Moses will be reassured to learn that God still works in wondrous ways. A sequel to the book, And If You Play Golf, You’re My Friend, arrived from Simon and Schuster last month. Moreover, the experience seems to have redeemed both the 89-year-old Penick and his 62-year-old coauthor, Bud Shrake.

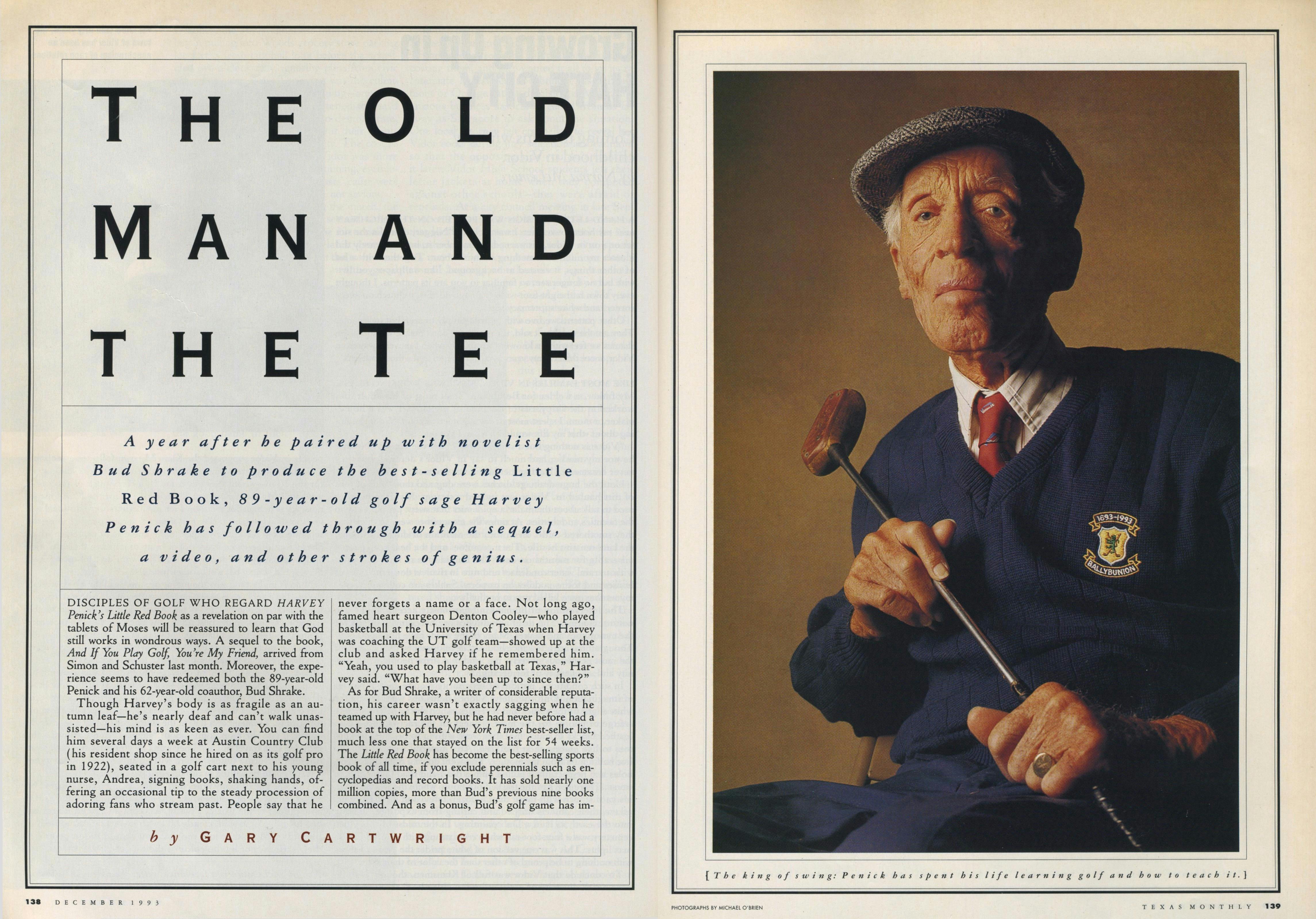

Though Harvey’s body is as fragile as an autumn leaf—he’s nearly deaf and can’t walk unassisted—his mind is as keen as ever. You can find him several days a week at Austin Country Club (his resident shop since he hired on as its golf pro in 1922), seated in a golf cart next to his young nurse, Andrea, signing books, shaking hands, offering an occasional tip to the steady procession of adoring fans who stream past. People say that he never forgets a name or a face. Not long ago, famed heart surgeon Denton Cooley—who played basketball at the University of Texas when Harvey was coaching the UT golf team—showed up at the club and asked Harvey if he remembered him. “Yeah, you used to play basketball at Texas,” Harvey said. “What have you been up to since then?”

As for Bud Shrake, a writer of considerable reputation, his career wasn’t exactly sagging when he teamed up with Harvey, but he had never before had a book at the top of the New York Times best-seller list, much less one that stayed on the list for 54 weeks. The Little Red Book has become the best-selling sports book of all time, if you exclude perennials such as encyclopedias and record books. It has sold nearly one million copies, more than Bud’s previous nine books combined. And as a bonus, Bud’s golf game has improved, at least marginally. “I’ve gone from shooting in the upper eighties to shooting in the lower eighties,” he says. Somewhat apologetically, he adds, “I’d be in the upper seventies if I’d listen to Harvey and spend three quarters of my time practicing my short game instead of banging away with my driver. ” In a chapter of the book that addresses the pigheaded tendency of most golfers to showboat their strength while ignoring their weakness, we are reminded that about half of any player’s shots are struck within sixty yards of the flagstick. “Bobby Jones said the secret of shooting low scores is the ability to turn three shots into two,” Harvey (and Bud) tell us.

In the year and a half since its publication, the Little Red Book has become a literary and cultural phenomenon, a sports version of the best-selling melodrama The Bridges of Madison County—but without that book’s sappiness and pretense. This shouldn’t really amaze us, but it does. Harvey Penick is one of the best-loved figures in golf, one of its last living pioneers. His influence has radiated across the world of golf for seventy years, directly or indirectly affecting the lives of thousands of players. Serious golfers from Texas to New York, from London to Madrid and Melbourne know Harvey by reputation, but until the Little Red Book appeared in print, no one fully realized the magic that his name would conjure. Here was a voice from the dawn of creation. Harvey started caddying at the original Austin Country Club in the Hyde Park section of the city in 1912, just 24 years after the sport was introduced in this country. (ACC claims to be the oldest country club in Texas, though Galveston Country Club makes a similar claim.) Harvey played on the Texas Professional Golf Association tour in the twenties, sharing transportation and hotel rooms and competing for meager prize money with the likes of Jack Burke, Sr., and Lighthorse Harry Cooper. He was president of the Texas PGA when two youngsters named Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson applied for membership. Harvey Penick may be the only person on the face of the earth who could offhandedly remark—as I heard him do recently while correcting a flawed backswing—“Walter Hagen had that same problem.”

In his thirty years as the golf coach at UT and in his decades as a club pro and an instructor at PGA schools, Harvey has taught some of the greatest golfers who ever lived—1992 U.S. Open champion and all-time leading money winner Tom Kite, 1984 Masters champion Ben Crenshaw, Don Massengale, Mickey Wright, Betsy Rawls, Kathy Whitworth, Sandra Palmer, and many others. Seven of the thirteen members of the Ladies Professional Golf Association Hall of Fame took lessons from Harvey. But he was much more than a teacher; he was a spiritual force and frequently a surrogate parent. They used to call the UT golf team Harvey’s Boys. When Sandra Palmer was struggling to make it on the women’s tour, Harvey and his wife, Helen, took her into their Austin home.

Along with grip and stance, Harvey taught honesty, integrity, and character. He was justifiably proud when Tom Kite won the U.S. Open, but he was even prouder when Kite sacrificed an opportunity to win the Kemper Open by warning New Zealander Grant Waite, who eventually beat him by one shot, that Waite was about to commit a two-shot penalty. “There is nothing guaranteed to be fair in either golf or life,” Harvey teaches. “You must accept your disappointments and your triumphs equally.” Harvey has always taken a deep satisfaction from the results of his teachings, not only when some former pupil won a major tournament but when an average weekend player hit a good shot and for one shining moment knew what it felt like to be a champion. “My greatest reward has always been the look of pleasure in the eyes of pupils who have just made a perfect shot,” Harvey says. This is not an exaggeration: Harvey has been known to shriek with joy and break out in goose bumps.

Almost from its inception, the Little Red Book seemed blessed with timing and an extraordinary reserve of goodwill. In May 1992, the same month the book went on sale, ABC commentator Jack Whitaker gave the book a lengthy and extremely complimentary plug during a lull on the network’s telecast of the Liberty Mutual Legends of Golf tournament in Austin. The following month, Golf Digest ran an excerpt and featured Harvey on its cover. A short time later Kite won the U.S. Open and immediately sent his trophy to Harvey. And then Crenshaw won the Western Open. In a matter of days everyone interested in golf was talking about the Little Red Book. The president of Pine Valley Country Club in New Jersey, one of the most famous and most exclusive golf courses in the world, confessed to Shrake that he had never read anything more interesting. An Austin couple taking a vacation cruise down the Amazon reported seeing another passenger engrossed in the Little Red Book. The owner of a New Age bookstore in South Austin began practicing the slow-motion drill described in the book instead of t’ai chi. Harvey’s son, Tinsley, went to Ireland partly to escape the hoopla of the book and immediately found himself cornered in an Irish pub by a native who couldn’t believe his luck at having encountered the son of the master.

Before the Ryder Cup in England in September, the London Daily Express devoted two of its seven pages of coverage to a story on Harvey—and on the Little Red Book, which was scheduled to be published in Britain the next month. The author described Harvey as “a mystical holy man” and wrote, “The Little Red Book… is only a manual of golf if Moby Dick is about angling and The Merchant of Venice is a guide to investment.” Predictably, the book’s warm reception has spawned a sort of cottage industry. So far there are audiocassettes and videocassettes, a calendar, and a newsletter. Harvey turned down several other offers, including an extremely lucrative one from Johnnie Walker Red Label scotch, which tried to buy 100,000 copies of the Little Red Book to use in an advertising campaign. Harvey explained to Bud, who would have received half of the royalties, that he didn’t want to encourage young people to drink. “Good for you, Harvey,” Bud said. One golf magazine wrote recently, “We’re getting Little Red Booked out. We’ve got the book, the video, the audio. What’s next, a 32 oz. drinking glass and Harvey Penick umbrellas?” “Hmmmm,” Shrake mused, “Harvey Penick umbrellas!”

THAT THE BOOK WAS EVER PUBLISHED in the first place is a small miracle. Harvey didn’t write it for publication. For sixty-something years, usually after a session with a pupil, he had jotted down tips and observations in a small red notebook that he kept in his briefcase. Most of the entries were spare and deceptively simple, homespun snippets of wisdom such as “take dead aim” or “swing the club like you would a weed cutter” or, alternatively, “swing it like you would a bucket of water. ” To nongolfers such pointers no doubt sound mundane, almost moronic, but every word in the book had, according to Harvey, “stood the test of time.” “Paralysis by analysis” is a phrase you hear frequently around a golf course: What Harvey has done is remind us that the object of this game is to hit a ball with a stick.

Until about three years ago Harvey had never showed the notebook to anyone except Tinsley, who had replaced his father as the pro at Austin Country Club when Harvey retired in 1971. A genuinely modest man, Harvey never dreamed anyone else would be interested. The notebook was to be Tinsley’s legacy, a compilation of knowledge and experience passed down from father to son. Harvey thought that he didn’t have long to live, and he believed that when he died, the club would fire Tinsley and hire some young hotshot who taught golf as though it were nuclear physics and broke down a golf swing into 45 distinct and separate movements.

In 1989 the end did indeed seem near. Harvey was admitted to St. David’s Hospital in Austin, suffering from a fractured spine, prostate cancer, disorientation, and severe depression. “Every day when I left the hospital, I thought it was for the last time,” recalls Tinsley, who is now in his mid-fifties. The depression was made more acute by Harvey’s feeling of uselessness. Then something wonderful happened. Messages (and money) began to pour in from club members and touring golf professionals. One message from Jack Nicklaus read, “Get well—we need you.” For the first time in days, Harvey responded to life. “Can you imagine Jack Nicklaus, the greatest golfer who ever lived, saying he needs me?” Harvey asked his family. “It’s unbelievable.” With the money that had been contributed, the family was able to hire a private nurse, and Harvey went home.

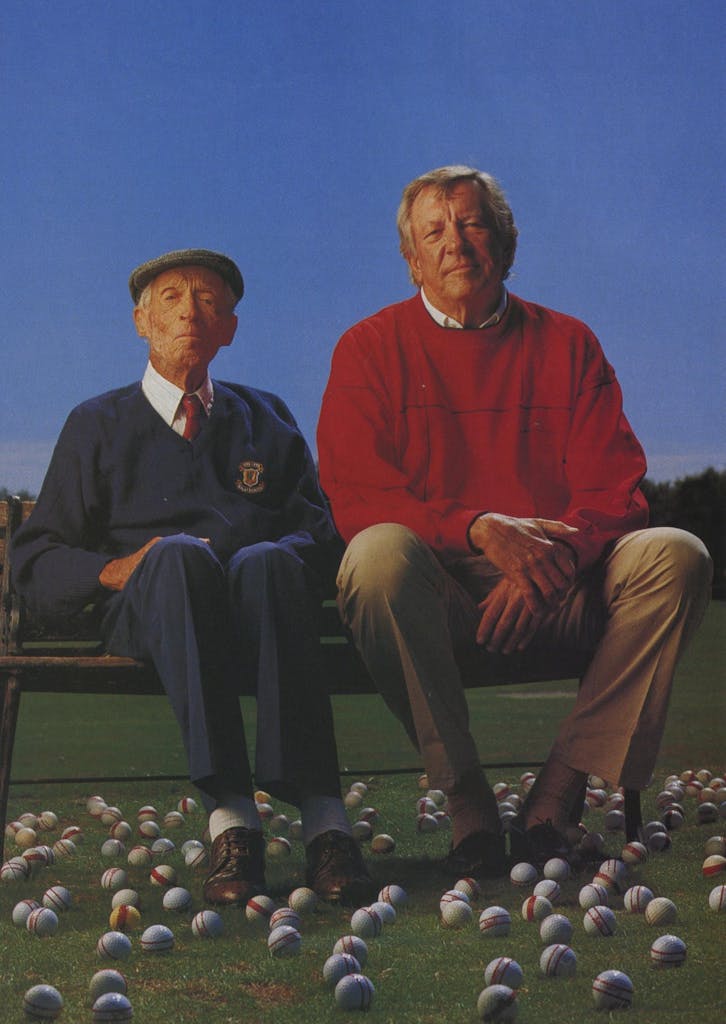

In the spring of 1991 Tinsley contacted Bud and asked if he could meet Harvey at the country club. Bud occasionally played at the club and had taken a lesson or two from Harvey. Mainly, his connection to Harvey was through Bud’s brother, Bruce, who had been one of Harvey’s Boys when he played golf at UT in the late fifties. Bud drove to the club and was directed to the practice tee, where Harvey and his nurse were waiting in the golf cart. The nurse stepped aside while the two men talked, first about Bud’s brother. Then Harvey said, “I’m about to show you something I’ve never showed anyone except my son, Tinsley,” and he produced the dog-eared notebook. “Do you think I could get this published?” he asked. Bud read a few pages and said that he probably could. Harvey continued, “Would you help me get it in shape?” Bud said that he would be honored. “How much do you think it will cost me?” Harvey asked, and Bud smiled and replied that he’d see what he could do.

Bud immediately called his literary agent, Esther Newberg, who was less than enthusiastic about the prospect of selling a book about a sport in which she had no interest, by a regional golf instructor whose name she’d never heard. Bud suggested that she get in touch with an editor at Simon and Schuster named Charlie Hayward, whom Shrake knew to be a sports enthusiast. Hayward passed the proposal along to the editor in charge of the sports books, Jeff Neuman, who instantly recognized the potential. Within a matter of hours, the publishing company offered a $90,000 advance. Bud telephoned the good news to Helen, who takes all of her husband’s phone calls since his hearing has failed. Maybe something got lost in the translation, but Shrake got the impression that Harvey was strangely noncommittal about the deal. The following day at the club, he learned why. Harvey asked Bud to sit beside him in the golf cart. In a voice so soft and feeble that Bud could hardly hear it, Harvey confessed that he’d been awake all night worrying about the proposal. “With all my medical bills and everything,” he said, “I’m not sure I can afford to pay ninety thousand dollars.” The serendipitous philosophy that led Harvey to seek out Bud in the first place—“When you’re trying to decide which club to hit, the first one that comes to mind is the right one”—persuaded the old man to put himself in Bud’s hands for the run of the project. In the beginning, nobody connected with the book believed it would make a lot of money: The publisher projected sales at 50,000, but hedged its bet by ordering an initial distribution of just 17,500. Still, it was apparent that Harvey and Bud were a match made in heaven. Shrake had published seven novels, including the classic Blessed McGill, written dozens of screenplays, and authored two best-selling as-told-to books with Willie Nelson and Barry Switzer. Publishing was a territory that Shrake knew well. And the subject was dear to his heart. “What Harvey had to say was so important that it had to be preserved for all golfers everywhere for all the ages,” Bud told me. “It happened to fall to me to make it happen. ” Since there wasn’t enough material in the notebook to fill even a thin volume, Bud began a series of tape-recorded interviews with Harvey. The interviews were slow and tedious. Bud had to sit facing Harvey and speak slowly so that Harvey could read his lips. Harvey’s voice was so weak that at times Bud had to hold the small clip-on microphone to the old man’s lips. Using the notebook as a starting point, the writer asked questions and the teacher elaborated on what he had already written, thinking of new things along the way. Once the tapes were transcribed, Shrake began writing short chapters, some only a paragraph or two, each on a subject that could be covered with a simple heading—“Hand Position,” “The Grip,” “The Waggle,” “The Right Elbow,” “How To Tell Where You’re Aimed.” “I wanted it to be like eating peanuts,” he said. “you read two or three chapters and you can’t stop.” Bud made several requests of the publisher, all of which editor Jeff Neuman supported. He wanted the book jacket designed to look as if it had been published a hundred years ago, he wanted it to be roughly the same size as the original little red book, and he wanted it priced at no more than $20. “Everyone who plays golf has twenty dollars and will spend it on anything that he thinks will help his game,” Bud reasoned.

As each chapter was typed, Bud gave it to Harvey to read and correct, another painfully slow process, but one that was absolutely essential to success. In the introduction to the Little Red Book, Ben Crenshaw writes, “What sets the great teachers apart from the others is not merely golf knowledge, but the essential art of communication. . . . Harvey has spent a considerable part of his lifetime . . . not thinking about what to say to a pupil, but how to say it.” A single word can make all the difference. Harvey tells students to place their hands on the club, the implication being not to grab or twist or wrap the hands around it. The success of the book can be attributed to Harvey’s clear, concise voice, abiding wisdom and integrity, and what Shrake calls “the purity of Harvey’s soul”—but it also owes much to Shrake’s skills as a writer and his own deep love of the game. Shrake told me, “The very thought that some serious golfer might take instructions from something that came from me rather than something that came from Harvey was terrifying.”

As a kid growing up in Fort Worth, Shrake used to follow his daddy around the golf course at Colonial Country Club, where the senior Shrake was a charter member. “My dad wasn’t a great golfer—he shot in the seventies—but he was good enough to play in tournaments,” Shrake says. “I loved the game, but I had no talent for it.” In the mid-sixties, when he was on staff at Sports Illustrated in New York, Shrake played occasionally with Dan Jenkins and some of the other editors, and he played in the annual 5:42 p.m. Open, a tournament staged at Wing Foot Country Club in Westchester County for the regulars at Toots Shors, the famous Manhattan bar.

After moving to Austin in 1967, Shrake continued to play sporadically, but he didn’t take up the game seriously until 1984—when his diabetes was diagnosed and he was ordered by his doctor to give up drinking. “I had to fill up my time doing something else besides drinking, so I took up golf,” Shrake says. With old friends Willie Nelson and Darrell Royal, Shrake played almost every day, from early morning until dark, 54 holes or more. Each golf shot is new life, new hope, Harvey teaches his pupils: A bad golf shot is a little death, but in golf there is life after death. There certainly was for Shrake: In the past nine years, golf has become more than a recreation—it has become his reason to be. “I love the way P. G. Wodehouse put it,” Shrake says. “Some people say that golf is a microcosm of life, but just the opposite is true: Life is a microcosm of golf.”

AS THE BOOK ZOOMED TO THE TOP of the best-seller list and stayed there, Harvey was inundated by success and having the time of his life handling it. He looked ten years younger. Normally when a writer publishes a book, he is expected to go on tour to promote sales. In Harvey’s case, the tour was coming to him. He was signing as many as 250 books a day and still requests were stacking up in the office behind the pro shop. “Harvey wrote so slowly and with such painstaking care that it took him about ten minutes to sign each book,” Bud recalls. “I bought him a signature stamp—it said ‘Take Dead Aim, Harvey Penick,’ and it was indistinguishable from the real thing. But Harvey wouldn’t use it. He said it wasn’t legitimate.” Many adoring fans, some traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles, popped by the club. So did old friends, some from Harvey’s school days. Invariably Harvey recalled their names. A man carrying a handmade golf club that his father had given him came by one day: Harvey didn’t recognize the man, but he recognized the club. “I made that club for a fellow in 1927,” he said, “’you must be his son.” He was. Letters poured in too, dozens of them every day. Many were simply messages of congratulations, but Harvey insisted on personally answering every letter that required a response. Two handwritten letters arrived from President George Bush. Harvey wrote back, “May I suggest that you are overanalyzing your swing.”

Wealthy golf nuts telephoned almost daily, wanting to fly to Austin in their private jets to take lessons from Harvey. Fielding the calls, Tinsley tried to explain that his father no longer accepted new pupils, that he was 87, deaf, disabled, unable to follow the flight of a ball down the fairway. Moreover, the callers needed to understand, Harvey’s teaching methods were not what most pupils expected. A lesson might consist of Harvey’s reaching out with his cane, moving a ball back a few inches, then driving away in his cart even as the student was asking questions. When he analyzed a student and decided he couldn’t help, Harvey simply drove away in his cart without a word. Sometimes he preferred hiding behind bushes while studying a pupil’s swing. Tinsley would tell the callers all these things and still some would persist. A textile heiress from North Carolina said, that she didn’t care what it cost, this was her husband’s birthday and nothing less than a personal lesson from the incomparable Harvey Penick would do. Tinsley sighed and told her to come on down.

Watching Harvey autograph books one day, Shrake noticed that he was using the phrase “to my pupil and friend,” even when addressing someone he had never seen before. Shrake asked him why and Harvey replied, “If they read my book, they’re my pupil—and if they play golf, they’re my friend.” Shrake mentioned this to Neuman later, and the editor said, “There’s the title for our sequel!”

And If You Play Golf, You’re My Friend is much like the red book in appearance, style, and substance: It is a compilation of tips, observations, and snippets of wisdom. The main difference is that the cover is green. No doubt it will come to be known as the Little Green Book. Material for the new book was collected from stories about Harvey that golfers had told Shrake after the first book was published, filtered back through Harvey himself for verification, and retold in his own words. “If Harvey didn’t remember a story, I didn’t use it,” Shrake said. This time the publisher did not hedge its bet: The initial printing was 300,000, and the company decided to bump that another 50,000 before the books were shipped. This book also costs $20. “It may sell as well as the first book,” Neuman told me, “but it will never feel the same. You only fall in love for the first time once. The Little Red Book is the happiest publishing story I know.”

CURIOUS TO LEARN HOW HARVEY and his family were dealing with success, I dropped by the club one morning in early October. Harvey was on the patio outside the clubhouse, seated as usual in his golf cart beside his nurse. Seven or eight women of various ages were clustered about, fawning over Harvey, and the smile on his face suggested that he was adjusting to life in the fast lane. “Imagine me, a caddie from Hyde Park, a C student who found it hard to write a single page of a theme in school, writing a best-seller,” Harvey said, beaming. Harvey and Helen continue to have a modest lifestyle, in a one-story townhouse near the club. Reluctantly, Harvey has agreed to a sevenfold increase in the fee he charges for a lesson—from $5 to $35. Teaching pros with half of Harvey’s reputation think nothing of charging $500.

Tinsley was more circumspect: The book has obviously changed his life but in ways that are not yet fully apparent. The success of the book has made Tinsley’s job more difficult. “People demand more than I can give,” he said. “I’m not like my father. Even though I know it’s the best advice I could give, I can’t bring myself to tell a pupil, ‘Swing it like you’d swing a bucket of water—fifty dollars, please.’ I just can’t do that.”

After lunch I walk over to the practice tee and watch Harvey give a lesson to Don Massengale, who lives in Conroe and plays the senior tour. Massengale is pushing his tee shot off to the right rather than hooking it like he wants to. Harvey instructs Massengale to lighten his grip and move his hands back. “Keep the club face square,” he, says, “and try to hit the ball over the shortstop’s head.” After about half an hour, Massengale is hitting the ball perfectly.

Later that same afternoon, Shrake is alone on the practice tee when Harvey drives up behind him just as he lurches at the ball and sends it dribbling down the fairway. “Oh, my, we’ve got a lot of work to do,” Harvey says. He has Bud take a few practice swings, then tells him, “You need to get back on your heels.” Bud tries it Harvey’s way and discovers that he is swinging smoothly instead of diving at the ball. “Now hit the ball like you’re mad at it,” Harvey tells him.

“Like I’m mad at it?”

“Like it’s your worst enemy.”

Bud crushes his next drive straight and true down the fairway, maybe the best golf shot he has ever hit in his life. He can’t believe what he’s just done. “Owwwww!” Harvey shrieks. And you can see the goose bumps popping out on his arm.