John Wesley Hardin, one of the most vicious outlaws of the Old West, killed at least two dozen men, including a Comanche County deputy sheriff in 1874. Hardin fled the state, but three years later John B. Armstrong, a Texas Ranger, tracked him down in Pensacola, Florida. Instead of shooting Hardin, Armstrong brought him back to Texas, where he was put on trial. It took half a day to pick a jury in Comanche, then another day and a half to try the case. The jury debated for three hours, found Hardin guilty of second-degree murder, and gave him 25 years. He appealed and lost; in September 1878 Hardin was sent to Huntsville, where he served almost 16 years before being released.

Bill Kroger believes that the way Texas dealt with Hardin says a lot about the state’s history. “Texas has a reputation as being the Wild West,” says the Houston lawyer, “but Jesse James was gunned down in Missouri, and Billy the Kid was gunned down in New Mexico. Hardin was brought to justice.” Kroger is chair of the state Supreme Court’s Texas Court Records Preservation Task Force and has become something of an unofficial state historian. “Texas wasn’t settled by gunmen,” he says. “It was settled in large part by developing, county by county, a system of laws, with due process, an independent judiciary, and a functioning bar of lawyers. It’s why the center of every county seat is not a church but a courthouse.”

In 2009 Kroger was looking through the archives of the Comanche County district clerk’s office and stumbled upon a record of Hardin’s history that had sat in the dark for generations. In a small room that resembled a closet, he found stacks of minute books, a kind of court diary that listed hearings, rulings, and decisions. Kroger opened one and was astonished to see the elegant calligraphy of justice on the frontier:

It is considered adjudged and decreed by the Court that the said John Wesley Hardin Defendant is guilty of murder in the second degree as charged in said Bill of Indictment and that he be punished therefor by imprisonment in the State Penitentiary and within the walls of said Penitentiary at hard labor for the term of Twenty five years. . . .

Discoveries like this have fueled Kroger, who for the past few years has traveled around the state, inspecting case files and minute books, trying to persuade people to preserve the history sitting in closets, sheds, and forgotten boxes. On some of these trips he’s been joined by his old law school buddy Wallace Jefferson, the chief justice of the state Supreme Court.

Their mission began in 2008, when Kroger wrote an article on Reconstruction for Houston Lawyer magazine and then started researching another on the noted jurist Nicholas Battle, a mid-nineteenth-century Waco judge and slave owner—who, as it happened, owned Jefferson’s great-great-great-grandfather Shedrick Willis. Kroger was particularly interested in Westbrook v. the State, a pre–Civil War decision in which Battle ruled that a freedman could not sell himself into slavery. Kroger was intrigued that a slaveholder would make a ruling in defiance of the ironclad community standards of his time. But all he could find online was a short appellate opinion. Where was the case file, the motions and pleadings?

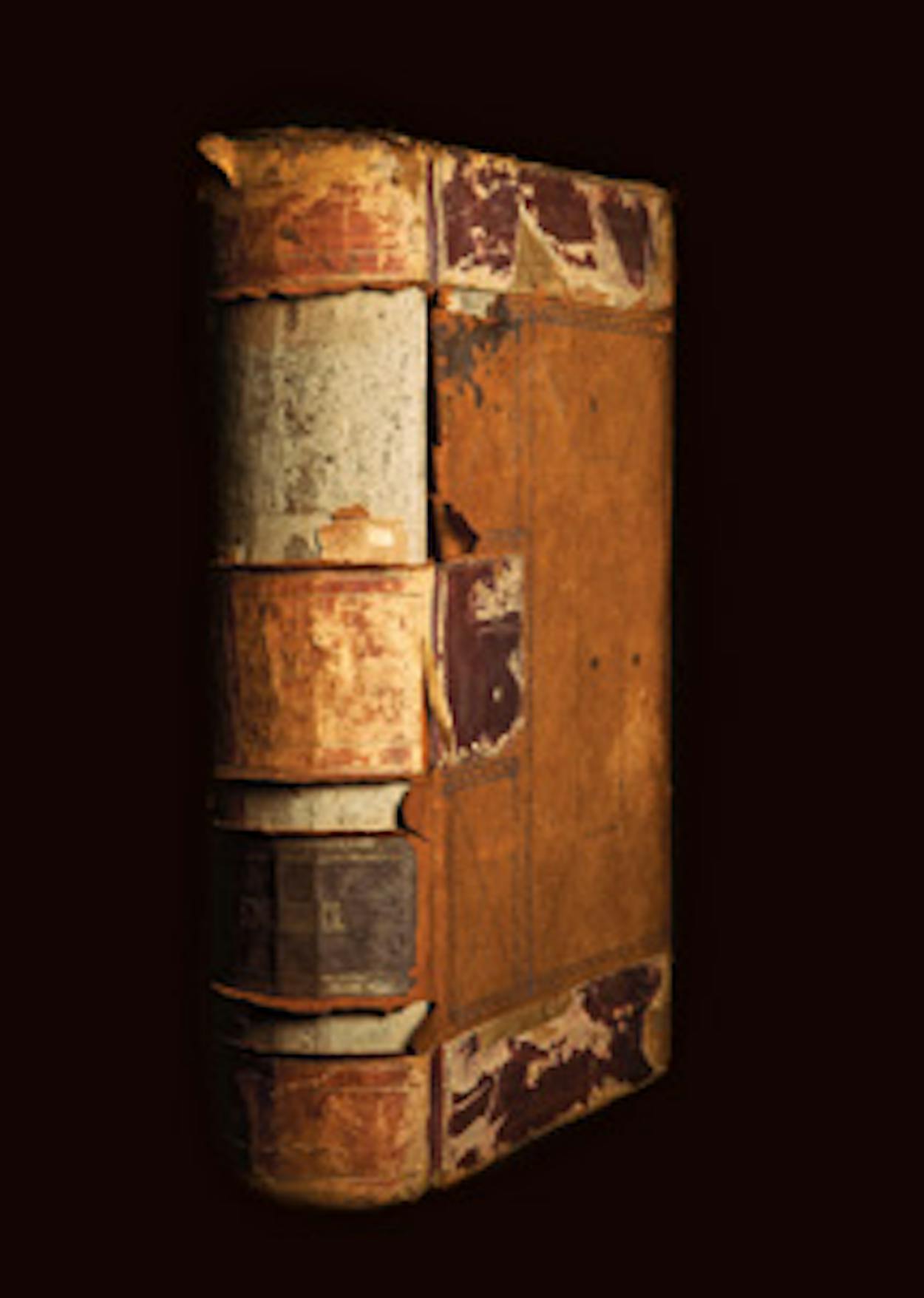

Kroger asked Jefferson, who is also a history buff, to take a trip with him to Waco to check the records for themselves. In December 2008 the two hit the road for the McLennan County archives, where they found nothing about Westbrook—no minute book, no case file. “What struck us,” says Kroger, “was how vast the district clerk’s records were, which had led to a certain amount of disarray. It was hard for us to tell which books they had and which ones were missing. All the case files were in their original envelopes. It was clear no one had ever looked through them—to even try would have risked destroying them. I remember touching some books and being worried that their binding would crumble in my hands.”

On the drive home from Waco, the two men talked about history and how so many invaluable records were vanishing or were simply impossible to find. Kroger suggested creating a task force of like-minded people to address the problem. Jefferson suggested doing so under the authority of the Supreme Court, which made sense, given that many of the cases he was hearing were connected by common law to those the courts had heard in the nineteenth century.

Three years later, what they have found in court archives in many of the state’s 254 counties has changed their whole sense of Texas history. “It’s a very different picture than the one we grew up hearing about, a richer, deeper view,” says Kroger. “I’ve always thought Texas history was centered on big events, like the Alamo, and important men, like Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin, and that the state was all pistols, barbed wire, and oil derricks. But that’s not how it played out in the lives of ordinary Texans. The state was slowly settled over an eighty-year history, and the history of Texas is really the story of hundreds of small groups of settlers trying to scratch out communities while facing conflicts and problems of all sorts. It’s 254 experiments.”

And the evidence of those experiments is disappearing. Texas, Kroger and Jefferson fear, is losing its history, one ancient court record at a time.

When Wallace Jefferson was growing up, his East Texas grandmother told him stories about her relatives, many of whom, in the years after the Civil War, had become educated—one worked as a dentist, another a lawyer, another a postal worker. His great-great-great-grandfather Shedrick Willis was elected twice to the Waco city council, even serving as mayor pro tem. Jefferson was intrigued. How did these people, who had been illiterate slaves, become professionals? In 1987 Jefferson and his father, William Douglas Jefferson, found Willis’s obituary at the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. “Deceased was one of the best known negroes in Waco,” it read. “[I]n assuming the duties of citizenship [he] was aided in many ways by his old master [Nicholas Battle].”

This piqued Jefferson’s interest. The evil slave master had somehow paved the way to a better life for the slave. “During Reconstruction,” Jefferson asks, “what were relationships like? There were problems, yes, but clearly people were trying various solutions. The former slaves had no land, no money, no education. Most became slaves again, indentured to landowners, but many got educated, became involved in politics. And they had to learn how to do it with the people who had owned them previously. How did that happen?”

Like many Americans, Jefferson’s ardor for history was fanned by the TV miniseries Roots, which aired in 1977, when he was a teenager living in San Antonio. But for most of his adult life, he worked on building a legal career. After receiving a political science degree from Michigan State, he went to the University of Texas law school, where first-year students sit in alphabetical order. Seated near him was young Bill Kroger. The two became friends.

Following law school, Jefferson started his own appellate firm in San Antonio. When he wasn’t arguing cases (including two before the U.S. Supreme Court—he won both times), he was researching his family history; in 1998, when he was president of the local bar association, he wrote an article about Shedrick Willis for the group’s journal, San Antonio Lawyer. Jefferson made history of his own in 2001, when he became the first African American on the state Supreme Court. Three years later, he became chief justice.

While Kroger and Jefferson share many qualities—they’re each in their late forties, married, with three children—their passion for history comes from different sources. For Kroger, it was discovering the early history of the law that he’s practiced for 22 years at Baker Botts, the oldest firm in Texas. “Looking at these records is spiritual, like going to church,” he says. “I’ve learned a lot about how to practice law from studying these documents.”

Kroger was raised in Houston, where his parents owned Parker Music, the state’s oldest music store. Working at the family business, Kroger met local and touring artists who came to play and hang out, such as ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, who helped spark his initial interest in history—Texas music history. He grew to love old blues and gospel greats like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Blind Willie Johnson and country giants like Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. After receiving an accounting degree, an MBA, and a law degree at UT, Kroger joined Baker Botts, rose to the position of partner, and began steeping himself in the history of the firm, which went back to the 1840’s. This growing interest led to a fascination with the history of Texas courts, which led in turn to Judge Battle, Shedrick Willis, the 2008 trip to the McLennan County archives with Jefferson, and the duo’s determination to rescue thousands of documents.

A spring 2009 meeting in Jefferson’s chambers with Harris County judge Mark Davidson and Galveston County district clerk Latonia Wilson led to the official establishment of a task force, a 29-member group of judges, clerks, lawyers, historians, and archivists. They weren’t sure what exactly was out there, so they decided to send surveys to the district and county clerks in every county in the state (district clerks handle a county’s bigger court cases, while county clerks handle the smaller ones as well as other records, such as probate, school, and property). What types of records do you have? they asked. How are they stored? Are they important? The answers—from 197 counties—were encouraging. Though most said their historical records dated from 1877 to 1920, about a third had records from the years just before the Civil War, and the archives of a fifth went as far back as the Republic of Texas. A few counties had material that predated the 1836 establishment of the republic.

Kroger decided to take a closer look, making fifteen trips in the next year; other members took trips too, though he was clearly the engine driving the project. Much of what he found was alarming: old papers stored in abandoned jail cells, shipping containers, unlocked closets, and—in one case—a shed, right next to the lawn mower. Minute books, their spines often coming undone, were stacked on the floor, beneath water and sewage pipes, or next to buckets of chemicals. In Bandera, a clerk told Kroger, “We got ’em in a railcar, down by the river.”

The truth is that, though many clerks are conscientious about the archives in their care, cash-strapped local officials often aren’t overly concerned about old court records. Many were falling apart, a result of low-quality paper and acidic ink, especially those from republic times. Others had been reduced to confetti by the heat or gnawed into oblivion by rats. Documents had been discarded by clerks who didn’t know better or stolen by people who did.

But Kroger found plenty that made him hopeful. Some counties (like Harris, Nacogdoches, and Bell) had climate-controlled buildings with spacious stacks. Others had already begun scanning and digitizing the documents. And even in the most dilapidated boxes, he and his fellow task force members found some indelible history, much of it in papers that had never been unfolded. There were records of the restraining order Lyndon Baines Johnson filed to keep Coke Stevenson from opening Box 13 in Jim Wells County, in 1948—the box Johnson supporters had stuffed with enough votes to carry the U.S. Senate Democratic primary. In Galveston they found the 1901 minute notes that showed a grand jury deciding not to indict boxers Jack Johnson and Joseph Choynski after the two had been arrested for prizefighting.

They also found plenty of history concerning ordinary people: suits brought against one another (over land and slaves, for instance), crimes committed (fornication, gambling), punishments suffered (the lash, the brand). They found divorce records, immigration records of some of the thousands of people who became citizens in Galveston (the Ellis Island of Texas), and probate records of slaveholders in East Texas—sometimes the only known records of their slaves’ existence.

The task force gathered what it had found, preserved some of the most historic items (with financial support from the State Bar of Texas and Baker Botts), and released its report last August. A month later the group made a presentation at the Supreme Court, showing off its findings about famous folks and those who never made it into the history books. When it was his turn to speak, task force member Mark Davidson quoted the author James Baldwin: “History is not a procession of illustrious people. It’s about what happens to a people. Millions of anonymous people is what history is about.”

In November, Kroger and Jefferson drove to Waco to see how McLennan County’s archives look today. It was a cool fall day, and the men walked through the archives in jackets and button-down shirts without ties, looking like what they were: successful lawyers casually dressed for a good time. Kroger has short hair and glasses and the air of an earnest kid with a clipboard. Jefferson is tall and thin, with a face made boyish by innumerable freckles. Though he was there for the progress report, he was also keeping an eye out for anything on his great-great-great-grandfather. “I would like to find a picture of him,” he said.

The archives building, which Kroger regarded as disorganized in 2008, was ordered and neat, with long rows of crisp metal shelving filled with color-coded binders. While Kroger looked through a 1935 beer docket (a record of all the businesses that sold alcohol), Jefferson perused the 1870 county registry, looking for any births in the Willis family. He didn’t find any.

Kroger was pleased with the conditions. “It’s clean and well lit,” he said. “The volumes are organized, the shelves are all labeled, and the case files are in protective boxes.” Though the task force has no real authority, Kroger believes it is making a difference, if only by letting county clerks know that someone is interested in the papers they keep. Lawmakers are taking notice too. During the last legislative session, the task force, working with state archivists and representatives, helped pass legislation to grant legal protection for all records created before 1951; previously the cutoff date was 1876.

The pair visited the office of the district clerk, Karen Matkin, who had laid out refurbished books and documents for their perusal. The holdings offered an expansive display of the area’s history, both the well-known and the hidden. “We have a Bonnie and Clyde,” said Matkin, opening up a minute book to show her visitors. “We were able to send him to the pen. He received a two-year sentence.” The entry bore Clyde Barrow’s name, with his alias, Elvin Williams. “The case file is empty, which makes me think someone stole it.”

Kroger opened another probate record book to the results of a September 1858 dispute over property—in this case, slaves. The verdict: “We the jury find for the plaintiff the following Negroes . . .” Then it pronounced a few names and values: Manerva $600, Anna $800. At the bottom was written, “Two children.” They were unnamed and valued at $350 each. One notable thing about court records, said Kroger, is that they don’t hide anything. “You see the horrors of the system in a very honest way.”

Kroger pulled some blue pages from an 1855 case file, but the pages were so stiff he couldn’t unfold them. “Here’s one of the big problems we’ve found. If a document hasn’t been properly preserved, you can’t even open it up without damaging or destroying it.” He looked over an old interrogatory from a case involving a man named John Millican, who said he had been an original member of Austin’s Colony—the very first Anglo community in what eventually would become Texas—and had helped draw an early map of the county. “This is another example of how, at an early stage of Texas history, we had a fully functioning, sophisticated legal system up and running,” Kroger said. “You had a formal set of written procedures for discovery and trial by 1846. You could subpoena records, take a deposition, ask for an injunction—the same things we as lawyers do today.”

Finally, he and Jefferson visited the county clerk, J. A. “Andy” Harwell, who also displayed some of his documents. One of them was a copy of a sale recorded on February 2, 1868, at eleven in the morning. Two men, “Shadrick” Willis and Mark Burney, were buying a piece of land in Waco for $100. Jefferson read the words carefully. Because he had already done so much research on Willis, the document wasn’t a big surprise. “I came up here years ago and found a box of deeds with Willis’s name on them,” he said, looking up. “He was selling property all around Waco; his son was a realtor.” No picture, no great revelations. Jefferson would have to come back to Waco some other day.

The document that impressed Kroger the most was a contract, written in December 1853, between McLennan County and Shapley P. Ross, the father of Sul Ross, who would one day take back Cynthia Ann Parker from the Comanche and become governor of Texas. In 1853 Sul was a fifteen-year-old boy, and his father had been running a ferry across the Brazos River for a few years. There were written agreements between Ross and the county for those years, but this one had much more detail. It said that Ross agreed to cross his ferry at Waco Village free of charge to “all Footman Citizens of said County—and also to cross all horseman citizens of said county free of charge except when the river is conveniently fordible [sic]. . . .” Waco wasn’t a city yet; there were no schools or main roads. But it had a free ferry across the Brazos, which would prove to be essential to the growth of the community.

“This is an astounding document,” said Kroger, who knew the story about the Ross ferry but had no idea this particular piece of paper existed. It seems almost certain that nobody did. Kroger ran his finger across the clear protective sleeve. The paper inside was old and yellowed, with beautiful cursive handwriting that flowed across the page. At the bottom was the signature of ferryman Shapley Ross, who didn’t realize that he was, quite literally, making history.