Every once in a while, Edwin Debrow dreams that he is a boy again. He is standing in a field of freshly mowed grass. It is a warm day, with no clouds in the sky. The sun is on his face. There are no smells of sweat and urine, and there are no sounds of steel doors opening and closing, no guards barking orders, no inmates shouting curses.

Edwin bends down and takes off his shoes. He begins to run—he hasn’t been allowed to run for his entire adult life—and his bare feet feel cool against the grass. He smiles. Soon he is laughing out loud. He throws his arms above his head. This must be what joy feels like, he thinks.

And then he wakes up in his bunk bed, in cell 37 of Building Three at the William G. McConnell Unit, a maximum-security state prison in the South Texas town of Beeville. He shuts his eyes and tries to fall back asleep. He wants to keep running. All he wants to do is run.

But the dream is gone.

Just after midnight on September 21, 1991, a San Antonio school teacher named Curtis Edwards was found sprawled across the front seat of a taxi that he drove part-time at night to earn extra money. He had been shot point-blank in the back of the head. It was a gruesome scene: blood and bits of brain were scattered throughout the car. A few days later, police announced they had made an arrest in the case. Edwards’s killer, they said, was a twelve-year-old boy named Edwin Debrow. Apparently, investigators said, Edwin had shot Edwards while attempting to rob him.

At the police department, a photographer from the San Antonio Express-News took a photo of Edwin as he was being escorted down a hallway by a uniformed officer and a detective. Edwin, who was just four feet eight inches tall and 79 pounds, was wearing a T-shirt, basketball shorts, and unlaced high-top tennis shoes. His face was peeking out of a suit coat that the detective had thrown over his head in hopes of protecting his identity.

Almost overnight, Edwin became one of Texas’s most notorious criminals. People were stunned that such a small child could have committed such a cold-blooded killing. A prosecutor for the Bexar County district attorney’s office called Edwin a “sick little monster.” In a speech addressing the problems of the inner city, President George H. W. Bush went so far as to single out Edwin, describing his behavior as “truly horrifying.”

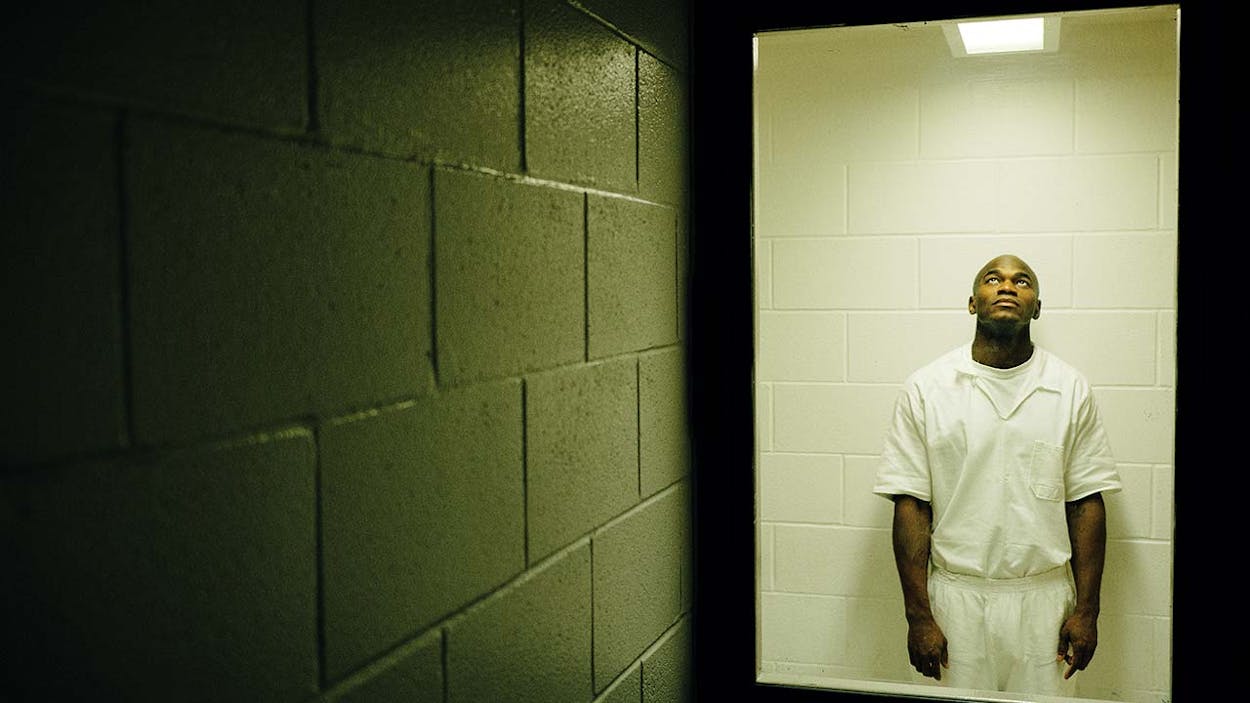

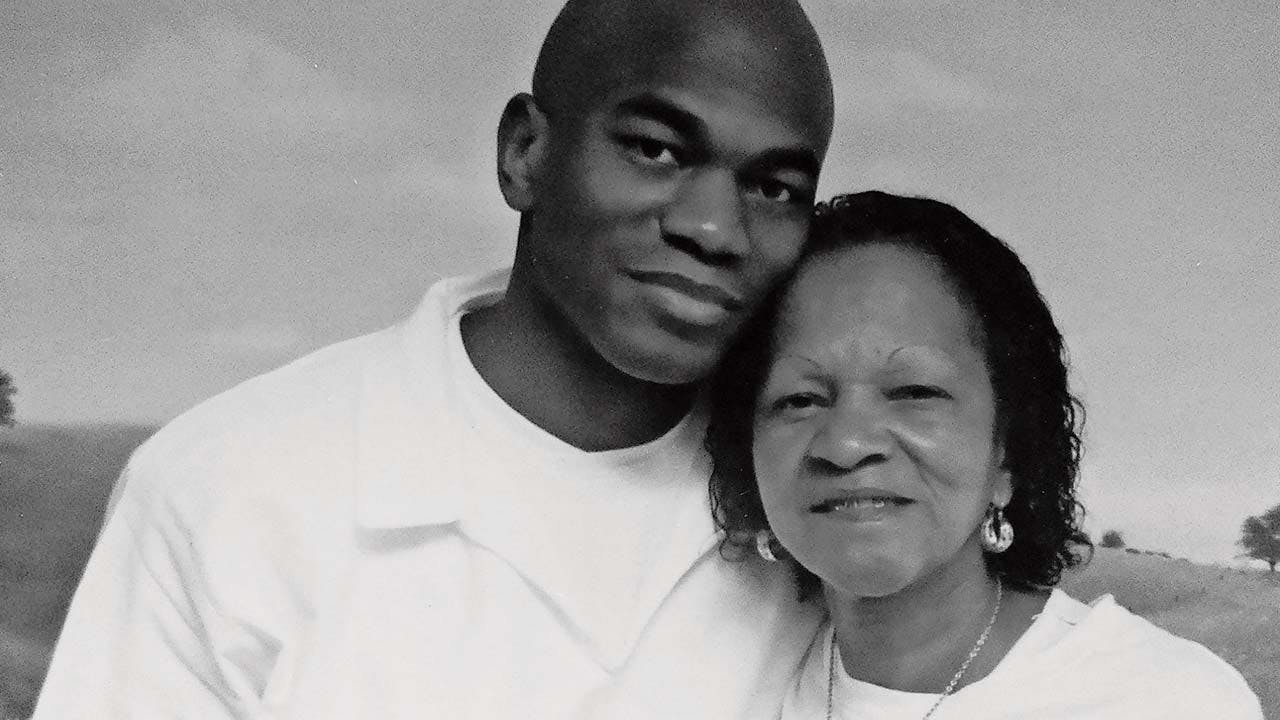

Today, Edwin is 37 years old. He is five feet ten inches tall, and he weighs 170 pounds. He looks a little like the boxer Floyd Mayweather, and because of the exercises he does every day in his cell—endless numbers of push-ups, crunches, pull-ups, and leg lifts—he is built like him too, with broad shoulders, a tapered waist, and biceps the size of baseballs. His head is shaved, and his arms and chest are inked with tattoos. “When my mom comes to see me, she always says I still look young,” Edwin told me during one of our conversations. “But I know she’s only trying to make me feel better. I know I’ve got the prison look.”

“The prison look?” I asked.

He gave me a thin smile. “The look of someone who’s not going anywhere soon.”

Edwin has been behind bars since the day he was arrested: he is now more than halfway through a forty-year sentence that a juvenile court ordered him to serve as punishment for Edwards’s murder. Although he has been eligible for parole since 1999, the members of the Board of Pardons and Paroles have refused to release him, always citing the severity of his crime. If he continues to be denied parole, he will not be released until September 2031. He will be 52 years old.

For decades, the members of the criminal justice system have argued about what should be done with kids who commit violent crimes. Lawyers, judges, police officers, politicians, and victims’ rights advocates have debated whether lawbreaking youngsters should be treated as regular criminals or as misguided delinquents with potential for rehabilitation. Is the public better served by putting them in adult prisons and keeping them off the streets for years and years? Or does the experience of incarceration only make them more disturbed and even more dangerous?

In Texas the law allows for very strict punishment of juvenile offenders. According to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, of the 140,000 inmates now housed in its prisons, approximately 2,000 are there for crimes that they committed as juveniles, which state law defines as anyone under the age of seventeen. Nearly a hundred of those inmates committed their crimes when they were only eleven, twelve, or thirteen years old. Of that group, only two have served more time than Edwin. “I’m considered the bad seed, the worst of the worst, all because of one stupid, terrible thing I did when I was twelve,” he told me.

He took a deep breath and slowly let it out. “Why can’t people understand I’m not that twelve-year-old boy anymore? Why can’t I be given a second chance?”

Some people who know Edwin believe he was never given much of a first chance. From the day he was born, in 1979, his life was marked by poverty and neglect, by drugs and fights, by knifings and gunfire. He and his six brothers and sisters were raised by their mother, Seletha, in shabby apartments and one-bedroom rent houses on San Antonio’s impoverished East Side. Dinners consisted of pork and beans, hot dogs, rice, and, as Edwin puts it, “straight-up corn.” Everyone slept on mattresses on the floor. When Seletha couldn’t cover her bills with her monthly $220 welfare check, the family would go for days without electricity and water. They ran a hose from a neighbor’s house to take showers. At least once they had to move into a homeless shelter. “I admit, I struggled,” Seletha told me.

She said that she had turned to liquor and crack cocaine because she couldn’t handle the pressure that came with making ends meet. She had a succession of abusive boyfriends, one of whom hit her in the face with a log. As for Edwin’s father, Edwin Debrow Sr., he lived in a nearby public housing project. Every now and then he would take Edwin and his other children to an arcade across from the Alamo, and he once took them to Schlitterbahn, the water park in New Braunfels. When they visited him at his apartment, he let them smoke pot and drink homemade wine. He occasionally took Edwin aside to teach him karate moves. “He said to me, ‘Edwin, you look like a baby,’ ” Edwin recalled. “ ‘The other boys are going to run over you.’ ”

So that he could buy groceries for his mother and candy for himself and his siblings, Edwin dug through dumpsters, looking for aluminum cans to sell. On Sunday mornings, he hawked copies of a San Antonio newspaper at a busy intersection. At night, when the television worked, he sat with his brothers and sisters and watched The Cosby Show and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. He danced around the living room to the music of M. C. Hammer. When the television didn’t work, he sat on the front stoop or wandered the streets by himself. He watched as drug dealers and prostitutes plied their trades. He once looked on as two men slammed a baseball bat over the head of another man. One night he saw his aunt bleeding from a knife wound just below her chin.

Edwin became disruptive in school, got into fights, and snarled at teachers who tried to discipline him. As a result, he was put in an alternative school, where teachers saw his promise. He won a ribbon at the science fair by filling a jar with water, placing a piece of cardboard over the opening, and turning it upside down without spilling any of the liquid. But he always came to school dirty and hungry. One teacher, Jacqueline Valentine, told her colleagues that she wished Edwin could come live with her. He had such potential, she said. She was worried that if nothing was done, he would turn out to be just another lost kid.

It happened sooner than anyone could have imagined. When Edwin was ten years old, he joined the Altadena Blocc Crips. He wore the Crips blue bandanna, flashed gang signs, and spoke gang slang. He began “pumping yay” (selling bags of crack) on a street corner called Jolly Time, which got its name because it was frequented by drug dealers. The other Crips called Edwin “the Baby Gangsta,” and he loved it. “I felt protected,” he said. “And when you’re a little kid running the streets, protection means a lot.”

He stole cars and went joyriding. Even though he hadn’t reached puberty, he gave hookers free dope in return for oral sex. He routinely packed guns. He committed small-time robberies, and he shot at a drug customer who ran off without paying. He went along with some other Crips on a drive-by, opening fire on a house where rival gang members lived. One evening, when he was walking down a sidewalk with some Crips, one of them shot a passerby in the face. Edwin and his pals then calmly strolled over to a Jack in the Box to eat hamburgers. “It was like I had no conscience,” he said. “I didn’t value human life. At that time, I thought it was better for some people to be dead.”

In 1991 he met a man named Floyd Hardeman, who had recently been released from prison after a murder conviction, charged with stabbing an 86-year-old man to death. Hardeman regularly dropped by to see Seletha, and she told her children that he was their uncle. In September of that year, just after he should have been starting the sixth grade, Edwin was arrested for criminal mischief: a cop had caught him trying to break into a car. Not wanting his mother to find out, Edwin called Hardeman, who came to the county’s juvenile detention center to pick him up. Hardeman, who needed drug money, then asked Edwin to help him commit a robbery. Edwin said he would. “I felt like I owed him,” he told me.

The night of the robbery, Edwin drank Thunderbird wine mixed with grape Kool-Aid. Around midnight, he and Hardeman hailed a burnt-orange Taxi Express cab driven by Curtis Edwards. A 33-year-old single father of a 6-year-old son, Edwards had also grown up on San Antonio’s East Side, raised by strong-willed parents who made sure he and his three brothers were home every night for dinner. He went to Rice University on a football scholarship. After graduation, he returned to San Antonio to teach. A member of Friendship Baptist Church, he gave away part of his earnings to help children that the church had identified as needy—children just like Edwin. He was full of life: every evening, he would walk into the office of the taxi company and loudly exclaim, “Merry Christmas and a happy New Year!”

Hardeman got into the front seat of Edwards’s cab, and Edwin sat in the back. As Edwards drove away, Edwin told him to hand over his cash. Edwards refused. Edwin pulled out a .38 caliber revolver, which he had been hiding in his pocket, and he shot Edwards in the back of the head.

The cab jumped a curb, plowed through a yard, ran over part of a flower garden, and hit a frame home. A resident who heard the crash came out on his front porch and saw Edwin climb out of the cab and wobble off down the street. Hardeman had already disappeared. Edwin was wearing only one tennis shoe. His head and nose were bleeding. He kept going until he passed out by some railroad tracks, where he was found and taken to Southeast Baptist Hospital.

At the hospital, still dazed from his head wounds, he told nurses, a security guard, and a chaplain that he had shot a man. At first, no one believed him. Edwin was only three months past his twelfth birthday. His arms and legs looked like Popsicle sticks. But the police were eventually called and Edwin was arrested. He admitted that he had decided to shoot Edwards on his own. When police interviewed Hardeman, he said he had no idea that Edwin was going to kill anybody. Prosecutors in the Bexar County district attorney’s office would later offer him a thirty-year prison sentence in return for a guilty plea of aggravated robbery, which he accepted. Then they turned their attention to Edwin: “I became public enemy number one,” he said.

Because he was too young to be certified to stand trial as an adult in a state district court (in 1991, the minimum age was fifteen), he was taken to juvenile court. At that time, young lawbreakers who appeared in juvenile court almost always received “indeterminate” sentences: depending on the severity of their crimes, their punishments ranged from probation—which they served either at their homes or at residential treatment facilities—to incarceration in state-run correctional facilities known as state schools. The amount of time they served at a state school was decided solely by juvenile authorities, but they were required to be freed before their twenty-first birthdays.

But the eighties had witnessed a sharp increase in juvenile crime, which was blamed largely on gangs and the explosion of crack cocaine. Citizens had been demanding that kids who committed adult crimes be given adult time. As a result, in 1987, the Legislature passed the Determinate Sentencing Act. It gave a district attorney’s office the authority to ask a judge or jury in juvenile court to impose a harsh sentence for a juvenile who had committed an especially violent crime. If convicted under this law, the juvenile was required to begin his sentence at a state school. Then, before his eighteenth birthday, he returned to court for a special hearing. If the judge decided the juvenile was sufficiently rehabilitated, he would either be returned to his state school and eventually released before his twenty-first birthday or he would be discharged completely. If the judge, however, decided that the juvenile was not rehabilitated, he would be sent directly into the state’s adult prison system to complete the remainder of his determinate sentence.

At the time of Edwin’s crime, four years had passed since the signing of the Determinate Sentencing Act, and the Bexar County district attorney’s office had never used it. Prosecutors decided that Edwin provided the perfect opportunity to send a clear message to San Antonio residents about bringing juvenile criminals to justice.

When the trial began, in February 1992, prosecutors warned the jury not to be fooled by Edwin’s age and boyish face. Yes, said Gammon Guinn, one of the prosecutors, Edwin was a child. But, Guinn continued, he was “a child that kills.” Guinn said that Edwin had strutted around “like a rooster” at the hospital, bragging about what he had done. Guinn then asked the jury, “Should we cut off society’s nose to spite our face and send him back out there? Do we let him do it again?”

Edwin’s court-appointed defense attorney, Andy Logan, did his best to portray Edwin as a victim of a sordid environment—a boy whose role models were gangbangers and ex-cons. Logan had Edwin’s school teachers testify about his intelligence. He argued that Edwin needed counseling, not punishment in a juvenile prison. “Let’s avoid pouring one more human life down the drain, placing one more human life in a warehouse for criminals,” Logan told the jury. “Let’s admit that he is a child and give him the one chance he’s never had.”

Edwin sat at the defense table, his legs dangling from his chair. He gazed around the courtroom without expression. “I wasn’t going to show weakness,” he told me. “I wasn’t going to give any of those lawyers a chance to call me a punk.” He paused for a moment and shook his head. “That’s how I had been taught back then. I had been taught to look strong no matter what.”

After deliberating for one hour and fifteen minutes, the jurors gave Edwin a 27-year sentence. When the verdict was announced, spectators in the courtroom gasped. Seletha, who was sitting in the front row, sobbed into her hands. For a moment, tears filled Edwin’s eyes, but then his face tightened. Before he left the courtroom, the twelve-year-old told a reporter that the verdict was “shit.” Then he was led away and taken to a police van. He was so small that the sheriff’s deputies had to lift him into the vehicle.

Edwin soon landed at the West Texas State School, a juvenile correctional facility located in an unincorporated area of Ward County, fifty miles southwest of Odessa. At that time, the state schools were teeming with gang members, and some Bloods, the Crips’ archrivals, lived in Edwin’s dormitory. When they heard the new boy had been a Crip in San Antonio, they quickly went after him. Although they were twice his size, Edwin fought back. He once put four Duracell batteries in a sock, which he used to beat a Blood over the head. “I had to fight, or I was going to be pushed over,” he said. “That’s just how it was.”

As the months passed, Edwin also lashed out at guards who tried to discipline him, and he even went after a teacher who criticized him in history class. He picked up a vase and threw it at her, hitting her in the face and fracturing her cheekbone. “I didn’t give a damn about anything,” he said. “I couldn’t see the end of the road. Fighting and rebelling were the only things I knew to do.”

None of his family members could afford to travel to see him, but he did get to talk to them on the telephone. For a while, he swapped a few letters with Sheila Bryan, one of his former school teachers. She sent him shoe boxes filled with popcorn and other treats. She wrote encouraging notes reminding him of his potential. But she eventually stopped writing, uncomfortable with the constant references in his letters to his fights and to his allegiance to the Crips.

Thinking a change of environment would help, administrators sent him to the Brownwood State School in 1993 and then to the Giddings State School a year later. A doctor prescribed him Thorazine, an antipsychotic drug used to treat mood disorders. Still, Edwin refused to change. He smashed the mirrors on a wall. He made wads of urine-soaked toilet paper called “piss balls” and slung them at guards and other staffers. He scrawled death threats on his cell walls with his own feces. He kicked at a toilet until the screws loosened, then ripped it off the floor. At least once he tried to escape. When writer Robert Draper took a tour of the state schools for a story he was reporting for Texas Monthly about juvenile justice (“Tough Love Story,” October 1996), an administrator pointed out Edwin and said that he was a born criminal who “can’t be fixed.”

On January 31, 1997, seven months after his seventeenth birthday, Edwin was brought back to San Antonio for his determinate sentencing hearing. Logan, Edwin’s attorney, was struck by how much his client had physically grown since his trial. But what shocked Logan was Edwin’s attitude. The teenager, he later said, “was so hardened it was unbelievable.” At the hearing, Logan tried to convince the judge that Edwin had been mistreated at the state schools. Edwin’s father also testified, declaring, “He was a child of twelve years old and was thrown to a pack of wolves. And you expect him to come out of this okay?” But when a state official testified that Edwin had racked up 178 misconduct reports during his time at the state schools, the judge had heard enough. Deciding that Edwin “clearly presents a continuing threat to society,” he ordered him to finish the remainder of his sentence in the state’s adult prison system.

Edwin was driven in a converted school bus—the “chain bus,” inmates called it—to Huntsville, where new prisoners are initially processed and classified. He was later taken to what was then called the Terrell Unit, where he was placed in a cell eight feet wide and ten feet long. It contained a lidless steel toilet and a steel sink, a small metal desk and chair bolted to the floor, and a bunk bed bolted to a wall. Older inmates, some of whom were built like bulls, stared hard at Edwin, saying nothing. Others were thin, their legs shaved. They whistled at Edwin, asking if he was ready to be their “f— boy.” Mentally disturbed inmates walked past his cell, mumbling threats. Hustlers sidled up to him and offered drugs or prison moonshine. One guard looked at Edwin and said, “Welcome to the rest of your life.”

Edwin didn’t flinch. Knowing he needed to bulk up, he began working out. He joined the prison Crips and arranged for an inmate to give him gang tattoos using a melted-down toothbrush and a sewing needle. “I let everyone know that I wasn’t going to be a punk for nobody. If they were going to come after me, then I was going to come after them.”

Edwin fought in the prison’s dayrooms, the hallways, and the recreation yards. In March 1998, when he was eighteen years old, he cut off a piece of a chain-link fence, sharpened it, and used it to stab a rival gang member, cutting open his chest and neck. (He was charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon in Polk County, where he received a four-year sentence to serve concurrently with his original sentence.) During another brawl, he hit an inmate so hard that he fractured his own hand. He even went after a couple of the guards who had pushed him around, throwing hot water in the face of one and trying to put a choke hold on another. “Prison is a harsh place for weak men,” Edwin said. “The only way I knew to overcome prison life was by confronting it head-on.”

By the time he turned twenty, Edwin had compiled a file folder full of misconduct reports. He had spent months in “ad seg,” or administrative segregation, an isolated wing of the prison, where he was kept alone in a cell for 23 hours a day and fed meals on a tray pushed through a slot in the door. Perhaps Edwin had not been born a criminal, but his experiences as an inmate—the brutal fights, the oppression of solitary confinement, the pervasive sense of vulnerability—certainly had consumed him with rage. He appeared to be exactly the kind of young inmate who, in the name of the public good, needed to be kept off the streets.

And then, he said, “I was ready to make a change.”

Social scientists and criminologists have known for a long time that the vast majority of young criminals stop committing crimes as they get older. In one study, a team of researchers tracked 1,300 young violent offenders over seven years. They found that only 10 percent of them committed a crime as an adult.

According to neuroscientists, the reason for such a behavioral shift is not very complicated: adolescents’ brains physically change as they get older. In particular, the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with behavior control, doesn’t completely develop until they reach their twenties. At that point, they are far less volatile and impulsive than they were in their teenage years. They are not as easily influenced by peer pressure. In other words, they grow up.

Was that what was happening to Edwin? Was he growing up?

“All I can tell you is that I got tired of rebelling,” he told me. “I felt different inside.”

Edwin said he had been having conversations with older black inmates, longtime convicts who warned him that he was going to die in prison if he kept fighting. He had also been reading a variety of books, including biographies of Muhammad Ali, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X, the activist in the fifties and sixties who preached the philosophy that a man can change his behavior if he changes his self-perception. He read Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson. (Jackson was a black revolutionary in the sixties who wrote about his attempts to rise above the dehumanizing experiences of prison. He was shot to death by guards in 1971 following an escape attempt from San Quentin.) He then read Makes Me Wanna Holler: A Young Black Man in America, by Nathan McCall, a young convict who later went to college and became a reporter for the Washington Post. “I realized that change was not a bad thing,” he said.

Edwin decided to write his own memoir of sorts, which he initially titled “Lost Boy” but later changed to “12-Year-Old Killer: The Story of My Life.” He sat on his bunk bed with a pen and lined notebook paper, and in raw, searingly brutal prose, he wrote about his chaotic days as a child running the streets. (“I learned to be a gutter boy, a gangsta, and a down right heartless nigga.”) He wrote about his vicious fights in the state schools and the prisons. (“I was like a madman. More or less like a walking time bomb waiting to explode. I had so much hate built up inside me.”) He wrote about the murder of Curtis Edwards. (“I randomly picked my victim. The black man I killed did nothing to me. He was just doing his job and trying to make a living to support his family. I had no reason at all to do what I did to him.”) And he wrote a revealing scene about a volunteer chaplain named Norman who visited him during one of his stays in ad seg. (“He asked me if I have ever wished for anything. I told him that I wished for a lot of things. But I wished more than anything that I could grow up again and forget everything that has happened in my life.”)

Edwin even composed a poem about the way his life had turned out. It began:

Isolated within a lonely prison.

All but forgotten so I keep my wisdom.

Tears running from a long distance.

My family love the most important thing I’m missing.

Can’t enjoy the tough times ahead.

Never can make up for the past that’s stuck in my head.

It seemed as if the boy who could not be fixed had a conscience after all. The more he wrote, the more the shame bubbled to the surface. “Writing,” he later said, “was how I found myself.” But that didn’t mean he became some sort of saint. “Man, prison is prison,” he told me. “The only prison saints you find are in the movies.” In 2004, for instance, when he was 24 years old, he was caught with a cellphone that a guard had smuggled into his unit, which Edwin said he had used to call his relatives, including his mother, who had been unable to visit him.

But there was no question he was changing. He also earned his high school equivalency degree that year. (He proudly told me that he was named valedictorian of his class.) He stopped running with the other Crips and later signed a statement with prison officials vowing to stay out of gangs. (“I felt like the gang shit was not for me anymore,” he wrote in his memoir. “I had did my dirt. Enough was enough.”) And he did something else unusual. He sent hand-written letters to the Bexar County courthouse, asking if he could get a transcript of his original 1992 trial.

Edwin was hoping to find some way he could appeal his 27-year sentence. The more he thought about it, the more he was convinced that the sentence constituted cruel and unusual punishment. “The juvenile justice system was created so that kids could have a second chance at life,” he said. “But it seems like our laws are tailor-made to keep the punishment going for the rest of our lives. What about the second part of our lives?”

Eventually a transcript was mailed to him at the William J. Estelle Unit, outside Huntsville, where he was being housed. With the help of a legal dictionary, he read every word of the transcript, including all the lawyers’ objections and the judge’s rulings. He discovered something important: the transcript was incomplete, missing the testimony of five key witnesses who had spoken in his favor. Edwin wrote a letter to the Fourth Court of Appeals, arguing that the missing testimony was vital to his original appeal.

The court assigned him an attorney, who put together a formal appeal. And in early 2007, in a decision no one saw coming, the appellate judges ordered that Edwin be given a new hearing in the same San Antonio juvenile court where he had originally been tried.

Edwin, who was 27 years old and had 12 years left in his sentence, was going to get another chance.

He arrived in San Antonio on the chain bus. He looked out the window, staring in wonder at a city he had not seen in years. Just before the hearing, Edwin wrote a letter to Jessie Mae Edwards, Curtis Edwards’s mother. He asked her to forgive him for murdering her son. He let her know that if he were ever let out of prison, he was going to make a difference in the world, perhaps follow in her son’s footsteps and help other needy kids. Edwin told me he did not write the letter in hopes of winning public sympathy. He only wanted Jessie Mae to know “how much I wished I could undo what I had done.”

But when Jessie Mae read the letter, her hands were shaking. “I felt like I had been slapped in the face,” she told me. “That boy wanted me to feel sorry for him. But he knew right from wrong when he shot Curtis. He knew what he was doing. He left me without a son, and he left Curtis’s own little six-year-old son without a father. He didn’t deserve a new trial. He should have stayed in his prison, grateful that he was still alive.”

It was, of course, impossible to overstate the grief that Jessie Mae and her family had been forced to endure. Anyone could understand their decision not to forgive Edwin. Still, there were other difficult questions the jury was going to have to answer. How long should someone pay for something he did as a child, even if what he did was commit a horrendous murder? Is it possible there’s such a thing as too much punishment? And is there such a thing as “mercy,” a word rarely used anymore in the criminal justice system?

It just so happened that two years earlier, in 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court had issued a landmark decision essentially saying that juvenile criminals did indeed deserve more mercy than adults. In a ruling that banned the death penalty for juveniles under the age of eighteen, the majority of justices took note of the recent scientific research about the changes that take place in the adolescent brain. They concluded that juvenile criminals are immature, impulsive, and susceptible to peer pressure—yet able to change for the better over time. “From a moral standpoint it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed,” wrote Justice Anthony Kennedy in his opinion. He also wrote that “even a heinous crime committed by a juvenile” is not “evidence of irretrievably depraved character.”

Although the Bexar County district attorney’s office asserted that Edwin needed to stay in prison because he had not shown evidence of rehabilitation, Edwin was convinced that a new jury would see that he had, in fact, changed for the better. He also had a small group of supporters who believed the time had come for him to return to the free world. One supporter, surprisingly enough, was Sandra Castro-Guerra, the forewoman of the jury at his first trial. She told a reporter that she was still haunted by the sentence she and the other jurors had given Edwin. “I think we did him an injustice, just because he was so young,” she told a reporter. “I don’t think he had the skills or the maturity to know better.”

When the hearing began, spectators and members of the news media filled the courtroom to get a look at the grown-up Edwin. Seletha and other members of his family came as well (his father, however, was in the Bexar County jail, serving time on a drug possession charge). Edwin’s court-appointed attorney, Lisa Jarrett, rose and told the jurors that Edwin had already served sixteen years for his crime. She noted that he had not gotten into serious trouble in several years and that he had had a spotless record for the past nine months. She had them think about the fact that he had spent most of his life in massive concrete buildings surrounded by fences topped with barbed wire, that he had never walked the halls of a regular high school, never legally driven a car, or never taken a girl on a date to the movies. “He’s missed his childhood,” she said. “He’s missed his early adulthood.” The time had come, she concluded, to let him return to his family.

Prosecutors, however, went through the gruesome details of how he had murdered Edwards. They brought witnesses to the stand from the 1992 trial who said they had listened to Edwin brag about what he had done. They also introduced evidence detailing Edwin’s violent behavior at the state prisons, including his 1998 stabbing of another inmate. In her closing statement, prosecutor Jill Mata told the jurors that if they chose to, they could add years to his sentence.

“Is it sad that we have a twelve-year-old that can do what he did?” she asked. “It is tragic and sad, but it is not your fault.”

The jurors stared at Edwin, with his shaved head and Crips tattoos and bulging biceps, and they quickly decided that he was not a person they wanted back out on the streets. They voted for a forty-year sentence—the maximum a juvenile who had not been certified as an adult could receive in Texas. Edwin would have to serve 13 years on top of his original 27-year sentence.

When the judge announced the jury’s decision, spectators in the courtroom looked on in disbelief. Edwin turned and stared at his family in the courtroom. For a moment, tears welled up in his eyes, just as they had at his first trial. But he quickly composed himself, and he was led away, taken to the chain bus, and driven back to the Estelle Unit. His buddies came up to his cell, shaking their heads and giving him a fist bump through the bars. One of the inmates told Edwin that he was probably the first person in the history of the Texas corrections system who had filed an appeal only to end up getting more time.

“Man, you’re snakebit,” another inmate said. “No one wants you out.”

A year passed, and then another, and another. In 2010 I wrote Edwin a letter, asking if he would talk to me about his life behind bars, and the next year I traveled to the Estelle Unit to meet him. A guard escorted him from his cell to the administrative building, took him to an interview room the size of a small closet, and locked the door behind him. I sat in an adjoining room. Between us was a pane of shatterproof glass. Edwin gave me a smile. “It’s nice to see someone from the outside,” he said.

We talked for a while about what his days were like. He told me he awakes at 5 in the morning, puts on his white uniform, shaves, washes his face, and brushes and flosses his teeth. He reads from a book of short biblical devotions for a few minutes, and at 5:30, he stands at the door to his cell, waiting for it to be opened so he can make his way to the cafeteria, where he works as a cook. At the end of his shift, he takes a shower. He goes to the dayroom to watch television with other inmates: Dr. Phil, Judge Judy, SportsCenter, and the network news. He returns to his cell and does his exercises. Then he makes his own dinner from items purchased at the commissary with the little bit of money his family sends him: usually tuna and mackerel spread over Ritz crackers, slices of turkey, pickles, and flour tortillas.

In the evenings, he either returns to the dayroom to watch more television or stays in his cell. Although he has stopped working on his prison memoir—he was waiting until he has a happy ending, he said—he writes letters to his mother, his sisters, and other relatives, promising them that he is okay. On occasion, when he feels especially lonely, he opens his footlocker, pulls out a photo album, and looks at family photos. On the last page of the album is the photo of himself that ran in the San Antonio Express-News on the day that he was arrested. Sometimes he looks at it—“to remember who I used to be,” he told me. By 10:30, he is in his bunk bed. He stares out a small rectangular window that provides a narrow view of a couple of buildings, a sidewalk, and a patch of grass. He stares at the ceiling. Finally, he shuts his eyes and sleeps fitfully until 5 the next morning. “And then I wake up to start my day all over.” He smiled again. “Every day, day after day.”

Edwin said he was continuing to try to improve himself. He had signed up for a few junior-college classes in business administration and computer science that were being offered at the prison. But he also admitted that he had had a couple of run-ins with prison authorities since the hearing. In 2009 he had again been caught with a cellphone. That same year he had been caught carrying on a romantic relationship with a female guard. (“We had sex in a prison closet,” he told me with a slight smile. “How was I supposed to turn that down?”) The violations had led to more misconduct reports and another stint in ad seg.

When I asked if he had heard anything recently from the Board of Pardons and Paroles, he sighed and pulled out a form letter he had received just a few weeks earlier informing him that he was not yet qualified for release, because “the record indicates that the inmate committed one or more violent criminal acts indicating a conscious disregard for the lives, safety, or property of others; or the instant offense or pattern of criminal activity has elements of brutality, violence, or conscious selection of victim’s vulnerability such that the inmate poses a continuing threat to public safety; or the record indicates use of a weapon.”

Because the Board of Pardons does not publicly release its files regarding its decisions, Edwin could only speculate why the board members overseeing his case wanted him kept in prison. Maybe, he said, it had something to do with his violations regarding the cell phone and the guard. “Or maybe they think something has got to be wrong with me because of what I did when I was twelve years old,” he said. “Maybe they think I’m so screwed up and that I’m going to kill again.”

Edwin reminded me that he had not received a misconduct report for violent behavior since 1999. Surely, he said, the parole board had to see that he had changed. He gave me a firm look. “I’m not dangerous,” he said. “I’m not a killer. Not anymore.”

The years passed and still he remained in prison. In 2015 he received a form letter from the parole board that contained an additional reason for why he should not be set free. “The record indicates that length of time served by the inmate is not congruent with offense severity and criminal history,” the letter read. Apparently, Edwin told me when I paid him another visit, the board members had decided he had not been punished enough.

Outside of his family, Edwin still had a small group of supporters, one of whom was Jerri Seibert, the owner of a San Antonio–area furniture store. She told me that she had written Edwin to let him know that she would have a job waiting for him whenever he was released. His former elementary school teacher, Sheila Bryan, also had begun writing him again, sending him encouraging notes along with some math workbooks, a dictionary, and The World Almanac and Book of Facts. “He is such a kind young man,” she told me when we first talked, in 2015. “It really is time to let him go.”

Nevertheless, members of Edwards’s family continued to write to the parole board, adamantly declaring that justice would be served only if Edwin completed his entire sentence. “That boy took the life of a good man, a very good man,” Jessie Mae told me. “Everybody who met my Curtis said he was a good man.” Her voice cracked, and she began to sob.

I last saw Edwin this past July, after he had been transferred to the McConnell Unit. He gave me his same pleasant smile. We talked for a while about the presidential campaign and the chances of the San Antonio Spurs winning an NBA championship without Tim Duncan. He told me that Sheila Bryan had sent him photos of an H-E-B Plus, the superstore that sells groceries, electronics, toys, housewares, apparel, and more. “Amazing how much they can put in one store,” he said. “You can get milk and some clothes, all in one trip.” I told him the world was going to look very strange and unfamiliar to him whenever he was freed, no matter how much television he’d watched in the dayroom. “Ain’t that the truth,” Edwin replied.

In the debate over juvenile crime and punishment, everyone agrees that juveniles who serve long prison sentences are woefully unprepared for that day when they are handed a cheap set of civilian clothes, a pair of shoes, and a little money for a meal and bus fare, and then sent on their way. “They have spent years being taught skills that are completely antithetical to functioning effectively in the real world,” said Michele Deitch, a senior lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin who has gained national attention for her research on juvenile offenders. “They’ve been taught to watch their backs at all times, to trust no one, and to throw the first punch in order to protect themselves. At the same time, they have no idea how to have a normal family life, a normal friendship, or a normal romantic relationship. These kids have grown up in little cages, enduring abuse and assaults that we can’t imagine.”

Just before he leaves prison—whenever that happens—Edwin will sit through a life-skills program, where he will be taught how to write a résumé, shake hands, and look people in the eye when speaking to them. But Edwin knows there is a lot more to learn. He’s never opened a bank account, never rented an apartment, and never applied for a job. He’s never even surfed the internet. “I know people think I won’t make it in the free world,” he said, and he sighed. “But I promise you, I’m never coming back here. I will be a success.” Besides working at Jerri Seibert’s furniture store, he told me that he hopes to publish his prison memoir. He also wants to work with teenagers from poor neighborhoods who are getting into trouble, because he believes he can persuade them to go straight. “I want to make a difference,” he said, and then he quoted his favorite Bible verse, from the Book of Jeremiah: “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.”

I asked Edwin what he will do on the day he is released. He said he’s going to go home and hug his mother (Seletha works in the housekeeping department of a San Antonio motel; his father died of cancer in 2012). He’s going to take a shower and “scrub the prison smell off of my body.” He’s going to go to church. He’s going to visit Curtis Edwards’s grave and beg for his forgiveness.

Then, he’s going to do something he is not allowed to do in prison. He is going to find a field of grass. He’s going to take off his shoes. And then he’s going to run. He will run for as long as he wants. He won’t have to worry about waking up from the dream.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Crime

- San Antonio