This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Known as the Jungle Road, the dirt track passes through an otherworldly thicket of palms, pines, and mangroves, one of the last primeval patches of Captiva, an exclusive little barrier island off Florida’s Gulf coast. Meandering past several white frame guest houses scattered over the 36 acres of prime real estate that Robert Rauschenberg has bought up since he arrived on the island in 1970, the Jungle Road abruptly ends at what looks like a misplaced museum, a gleaming modernist step pyramid rising from the semitropical forest as improbably as a Mayan temple. This is Rauschenberg’s studio, built five years ago on pillars sunk so far into the bedrock that the artist could go on working even if the entire island vanished in a category-five hurricane.

The main studio is the size of a gymnasium; facing the mainland, a wall of glass doors overlooks a broad flight of steps descending to the minimalist blue rectangles of the terraced pool and spa. Here the visitor realizes that Rauschenberg’s workplace has conflated the functions of studio and museum, a logical step for a working artist who long ago was assigned a prominent place in the history of art.

Eisenhower was in his first term when Rauschenberg began to transform the art of our time in a $10-a-month loft in New York; that it is impossible to tell the story of post–World War II painting, sculpture, printmaking, dance, or performance art without a representative Rauschenberg is a fact that museums around the world have recognized for at least thirty years. Throughout those decades Rauschenberg has been so prolific that the current retrospective of his work requires all three of Houston’s major museums just to survey its bewildering, multimedia variety: solvent transfers on sheer silk and silkscreens on metal sheets, stage props and a sculpture that spews mud to music, a painting that can be walked into, and a still-evolving assemblage of thousands of images and objects that requires a stroll of almost a quarter of a mile to see it all. (“Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective” is now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Contemporary Arts Museum, and the Menil Collection, which organized the exhibition, through May 17.)

So Rauschenberg’s Captiva studio is, like most museums, a monument to success: the marketplace triumph of art once considered scandalous even in the tiny club that was the New York art world in the fifties; the extraordinary capacity for reinvention of a man who should have been swallowed up within a few years by the wave of innovation that he, more than anyone, set in motion. But the Captiva studio also has a deeper meaning. It is the monumental evidence of an epic migration that began on another coast, among the fire-and-fume-belching oil refineries of Port Arthur, and crossed a psychological gulf far wider than the water that separates Texas and Florida. In Captiva, looking up at this shrine to probably the most influential artist of this half of the twentieth century, it is almost impossible to imagine the distance that a boy named Milton Rauschenberg had to travel to get here. Yet in talking to the 72-year-old Robert Rauschenberg, it quickly becomes clear that he would not be here if he had not been there.

A lot of the reporters, if they’re not quoting me, have a very vivid misunderstanding.

—Robert Rauschenberg, 1998

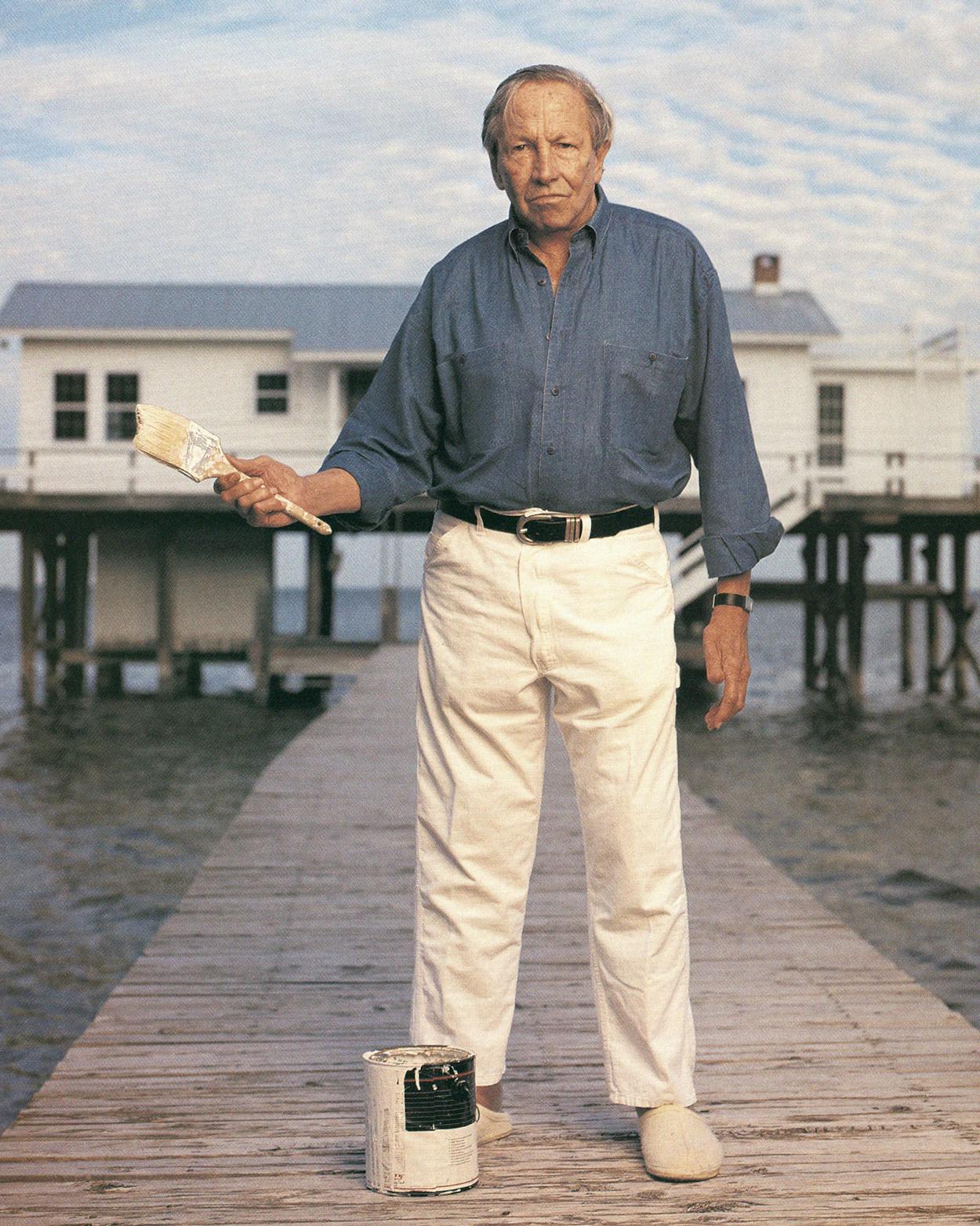

When a writer and a photographer arrive at the starkly rectilinear white-stucco house that Rauschenberg built several years ago at the Gulf end of the Jungle Road, the artist introduces himself as just “Bob,” then offers some further identification: “I’m your victim.” He plays the victim as gracious host, however, serving his inquisitors crab gumbo, which he cooked himself, at the L-shaped bar at the far end of a spacious white-tiled living room. And there the man who says he forgot his lines in his only stage appearance at Port Arthur’s Thomas Jefferson High School—but who practically invented the category of performance art in collaborations with such equally legendary innovators as composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham—begins a classic Rauschenberg performance: the Port Arthur stories delivered in a courtly Southern bass, the wordplays and bon mots tossed off with dazzling nonchalance. On his 95-year-old mother, expected at the Houston opening: “She still doesn’t want her friends to know what I do. But she’ll go on my trips.” On his youthful social shortcomings and academic failures: “I was aggressively introverted. . . . I was dyslexic, you know. The only thing I could do was dance.” On his triumphal return to Port Arthur, in 1984, when he apparently exorcized the demons: “I tried all my old haunts and found I wasn’t haunted at all.”

After lunch it’s down the Jungle Road to the studio, where Bob, a visionary widely praised for his uncommon respect for other artists’ vision, affably submits to photography. During a break he sips wine and wanders among huge worktables piled with computer scans of his own photographs printed out on glossy paper in water-soluble inks that allow the images to be transferred when wetted and pressed onto large sheets of paper laminated to metal; the effect is that of collages reproduced in watercolor. A generic price list, graduated by size, lies on one of the tables. The largest pieces, up to sixty square feet, run well into six figures.

But Bob isn’t looking at the price list when suddenly he says, “I misunderstood you. How was I to know you could sell this shit?”

“What?”

“My father said that.” Rauschenberg’s father died just months after the artist’s first retrospective, at New York’s Jewish Museum, in 1963.

“And those were the words he used?”

“ ‘We never wanted you to be an artist. But we didn’t understand. How were we to know you could ever sell this shit?’ ”

So began another journey back to Port Arthur.

I was stuck there. And it wasn’t until I was drafted into the Navy that I had any idea that Port Arthur wouldn’t be eternal.

—Robert Rauschenberg, 1998

Rauschenberg often tells the story of how he had never visited an art museum until he was nineteen years old. Sight-seeing as a Navy hospital corpsman in training in Southern California, he ended up one day at the Huntington Library in San Marino, in front of two eighteenth-century English portraits (Thomas Gainsborough’s Blue Boy and Thomas Lawrence’s Pinkie) he had previously known from the backs of playing cards.

He had shown a talent for designing posters and sets for high school plays and had drawn portraits for his boot-camp buddies to send home, “without the realization that that was something you could do.” Looking at the source of those playing-card images, he told a critic several decades ago, he suddenly realized, “Behind each of them was a man whose profession it was to make them. That had never occurred to me before.”

That sort of isolation is difficult to grasp without understanding the particular circumstances of Rauschenberg’s upbringing. His father, Ernest, could have told his own Texas Gothic tale: The son of a German immigrant who married a Cherokee woman and became a farmer in Gatesville, Ernest was not yet seven when his mother died; shortly thereafter, he was pulled out of school to work on a farm until he was seventeen, when he embarked on his career as a lineman with Gulf States Utilities.

Ernest’s only son, Milton, was born in 1925 and raised in the strictly fundamentalist Church of Christ. “The Church of Christ made the Baptists look like Episcopalians,” Rauschenberg recalls. “There wasn’t an idea you could have that couldn’t lead somebody else astray.” Intending to be a preacher, Rauschenberg, then a teenager, lost his calling “because it was a sin to dance. And I was quite good at looking through the Bible and showing how many times they danced in the Bible.”

Rauschenberg remembers a determined quest to escape the grim monotony of small-town life in an industrial setting. He taught his father’s Labrador, Red, how to climb the chinaberry tree in the alley and kept a collection of live insects under the house. (“It’s very hard to keep a good collection of live bugs.”) Many evenings he would wait for the six o’clock train to come roaring down toward him while he gripped the track with his hands. “I’d hang on to the track until I couldn’t bear it anymore and then would just roll down the levee. I fantasized making it a little longer every night. I’d roll down that levee in ecstasy.”

One rainy day ten-year-old Milton Rauschenberg decided to paint his entire room with red fleurs-de-lis. His father punished him, he recalls, “but it was just some more trouble. No more serious than having, nearly every night, to leave the table because I would start laughing. ‘There’s nothing funny,’ my father would say. I didn’t stop laughing, so I’d have to go out and stand in the dark.” Milton also laughed in church while rhetorical fire and brimstone rained down on the congregation. “As my mother once said, ‘I think he was the only child that was ever taken outside because of his laughing.’ Because most of the kids were crying. I think I annoyed people by being happy. Which was the only thing I had.”

I’m not interested in being a great artist. I am an artist.

—Robert Rauschenberg, 1998

After his discharge from the navy in 1945, Milton Rauschenberg returned home, only to find that his family had moved—without telling him—to Lafayette, Louisiana, where Ernest had been promoted to line foreman. Even so, the profound inertia of his childhood kept Rauschenberg in Port Arthur for several desultory months. “Somehow it was a fact that I had to go back to Port Arthur,” he says. “I tried to stay there, and it took me about six months to realize that I really did not have to live in Port Arthur, that there was the rest of the whole world. That’s when I went out to Los Angeles.”

In Los Angeles Rauschenberg worked at menial jobs for a year before a designer at the swimsuit factory where he worked took him under her wing and arranged for him to enroll at the Kansas City Art Institute. At the bus station in Kansas City, Missouri, Milton decided he wanted a more familiar name and introduced himself to the first person he met as “Bob.”

Guided by some internal compass as mysterious as human creativity, Bob Rauschenberg took off on a rocket ride from utter innocence to the outer limits of artistic freedom. In 1948, a year after arriving in Kansas City, he was studying in Paris under the GI bill. Later that year he enrolled at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, then the most potent avant-garde think tank in the world; he had read about the innovative, multidisciplinary college in Time magazine while in Paris. In 1951 Rauschenberg showed his daringly abstract white paintings on newsprint and maps at the New York gallery owned by Betty Parsons, the dealer for grave Abstract Expressionist eminences like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, themselves still struggling for recognition outside the tiny community of the New York avant-garde.

By 1954, Rauschenberg had begun making his signature “combines,” painting-sculpture hybrids that irreverently combined emotionally charged Abstract Expressionist brushwork with such deadpan discards as old tires and a stuffed goat. One of his most notoriously insouciant works was 1955’s Bed; lacking a canvas, he simply painted on an old quilt, sheet, and pillow. Rauschenberg credits his mother, an expert seamstress who seemed to be able to lay out an entire dress pattern on a scrap of fabric no one else could use, for inspiring his make-do approach to art. “It was an attitude I got from her. Once a piece of material that has been selected, designated, or accidentally found is your ground, you don’t want for more. You have to make that the whole experience.”

As the Abstract Expressionists became international icons, Rauschenberg’s canvases, laden with pieces of clothing, newspaper clippings, and Coke bottles, inspired Pop artists like Andy Warhol, soon to emerge on the scene; the boy from Port Arthur had laughed in the Abstract Expressionists’ temple of metaphysical angst, and a new generation was laughing with him. But there was also a philosophical gravity to Rauschenberg’s high jinks. Mark Rothko once said that the only subject matter valid for painting was the “tragic and timeless”; Rauschenberg’s work suggested that the artist should embrace everyday life, that the most common things could be art’s subject and substance. And while several generations of critics have continued to derive esoteric messages from Rauschenberg’s barrier bashing, he has always seen himself as a populist who hoped to demythologize art, to take it out of the hands of a privileged elite. “I don’t think I’ve ever worked without having in mind that I somehow want to touch everybody’s sensibility,” he says. “And even though communication in art has been out of fashion for such a long time, I’ve never given that up, no matter how abstract the work is. It’s really meant to be put right in front of somebody. And that can be anybody.”

I could hear the same thing in Janis Joplin’s voice. That kind of blues . . . that was Port Arthur.

—Robert Rauschenberg, 1998

Fame eventually brought Bob Rauschenberg home, for an exhibition at the Port Arthur Library and Historical Association in 1984. It was an experience he dreaded. “It was so unimaginable that I would ever live so successfully outside of there that it was rather frightening that I would expose myself to it again,” he says. “I went back for my mother. That show at the library was more important to her than if I was doing a one-man show at the Louvre.”

But Rauschenberg knew what had happened to another nonconforming alum of Thomas Jefferson High School. He had met Janis Joplin (class of 1960) at a New York bar in the late sixties, when she sent him a note that read “We’re the only two people who ever got out of Port Arthur, Texas.” They became close, and Rauschenberg was with Joplin shortly before she went back to Port Arthur for her tenth-year high school reunion. “We sat up all night drinking tequila,” he remembers, “and I begged her not to go back. And she said, ‘I just want to show them who ah am.’ And I said, ‘I feel you’re even more desperate if that’s why you’re going back.’ ” His tone is admonishing, as though he is still angry at an intimate who committed suicide.

“She did not impress anybody,” he says. “All the people that she was thinking might say, ‘Hey, welcome back, girl,’ disliked her even more.” Less than two months after that reunion, the only other person ever to get out of Port Arthur was dead of a drug overdose.

Rauschenberg, however, had a more forgiving cushion of time. “If there was anything I could have felt sentimental about, it wasn’t there anymore,” he says of his 1984 visit. Of course, by then the ghosts had already made themselves at home in Captiva, where they can still be found fourteen years later, flocking on a sunny winter afternoon like the buzzards wheeling over Rauschenberg’s jungle. They are the source of the doubt that compels a living legend to comment that he is grateful for his retrospective because after looking at it (the show opened last fall in New York), “I figured out that I didn’t have to be ashamed of myself.”

But those ghosts are also the custodians of the enduring innocence of a nineteen-year-old who had never visited an art museum, of the renewable capacity for awe that has allowed Rauschenberg endlessly to refresh his vision amid the multimedia clamor of a world he long ago prophesied. “It’s an attitude I’ve worked hard to maintain,” he says. “If you lose that sense of wonder, that curiosity, that ability to be surprised, then you’re going blind.”

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Port Arthur

- Houston