After years of counseling and prayer, John Ray decided he had finally developed the emotional fortitude to revisit the formative trauma of his youth. He started a private Facebook group, titled simply “Murchison/Mr. Grayson 40 Years Later,” and invited former classmates and teachers to join. Ray wasn’t entirely sure how his outreach would be received. He knew only that he couldn’t confront the past alone.

For one thing, Ray barely remembered the details of that day—May 18, 1978—when a friend at his Austin junior high school walked into class and, in front of Ray and twenty other eighth graders, shot and killed their teacher, Wilbur “Rod” Grayson. In fact, Ray barely remembered a single thing about that entire year. Much of it had been buried in the far reaches of his subconscious, where over the years it had massed like a tumor.

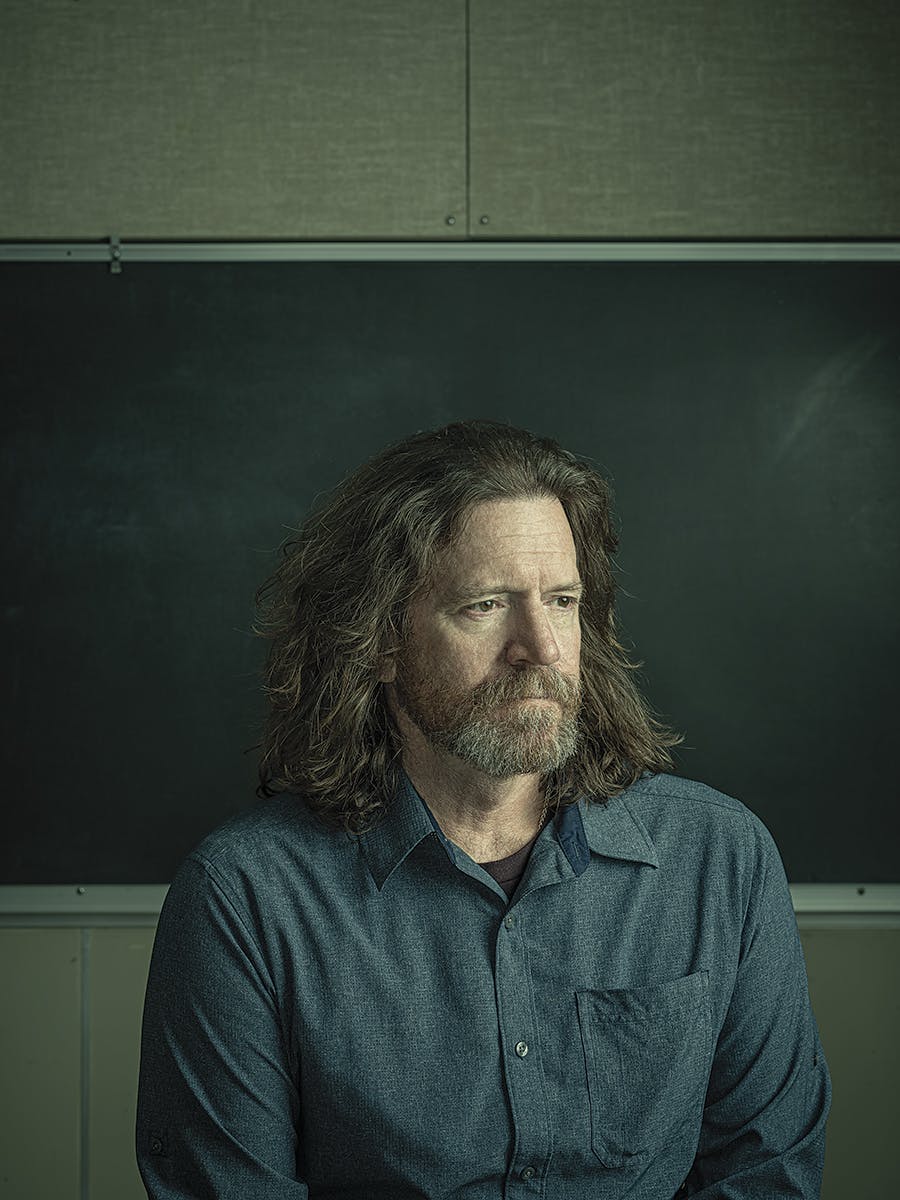

Ray, now 56, lives in Fayetteville, Arkansas, with his wife and three daughters. As an ordained nondenominational minister, he is decidedly unorthodox: he tends to preach outdoors, in natural settings; he wears cowboy boots and untucked denim shirts; and he has a Christlike mane of hair. He spends much of his time offering spiritual solace to those who have experienced trauma—people who, according to Ray, “have suffered and know my suffering and will call me on my bullshit.”

It occurred to him that he might be able to comfort his Murchison Junior High classmates, even as he leaned on them. So in February 2018, Ray created the Facebook group, and he waited. Several of his classmates who had been in the room that morning didn’t respond to Ray’s invitation. But others, including some who hadn’t witnessed the shooting, thanked him for initiating the collective remembrance.

Many shared memories of Mr. Grayson, as they still called him—how he had once taken the entire class to New Orleans to see a King Tut exhibit; how he had helped his students launch a magazine called Serendipity Doo-Dah; how he was “sharp and interesting and challenged us to think outside our normal convention.” Someone posted a forty-year-old newspaper clipping with the headline “Gifted Student Shoots Teacher” and, beneath it, a photograph of their thirteen-year-old classmate shielding his face from cameras.

“That was such a traumatic time,” a former student wrote. “I was on the field just outside the window when it happened.”

“It was a defining moment in my life,” added Marilyn Eichenbaum DuVon, Grayson’s teaching partner at Murchison.

Someone posted a chart that Mitsuno Baurmeister, now living in Northern California, had painstakingly diagrammed, days after the tragedy, of where each of them was sitting when the shooter stepped through the doorway.

Overwhelmed by the torrent of memories, Ray announced to the Facebook group in March that he would be traveling to Austin a few days before the anniversary of the shooting for a previously planned writing workshop. He asked if anyone wanted to meet up. Someone suggested they visit Grayson’s grave site. Several classmates agreed to gather there.

The morning of May 18, after finishing his workshop, Ray climbed into his burnt-orange Honda Element. He headed to a local coffee shop, where he’d planned to meet a few classmates before driving to the cemetery, and on the way he heard on NPR that there had been another school shooting in Texas, in the town of Santa Fe, south of Houston.

In an instant, a familiar sensory pandemonium overtook him. His fingers and toes began to tingle. His breathing became shallow. His eyes darted around in search of airplanes plummeting from the sky, a jarring hallucination he’d experienced before. He was a thirteen-year-old boy again, panicked that he was about to be killed.

Just as quickly, he jolted back to the present. But the images and sensations continued to ricochet inside him as he arrived at the coffee shop.

He hadn’t seen his old classmates in years, and they hugged and tearfully greeted one another. As they caught up, someone inevitably brought up the students at Santa Fe High School. Great, Ray thought. Now a whole other generation gets to spend the next forty years of their lives dealing with this shit.

Eventually, they drove together to Assumption Cemetery, on the south side of Austin. One of them brought a towel and some cleanser to scrub their teacher’s gravestone. Another brought flowers. For an hour, five of them stood on the dry, unshaded ground, offering words of thanks to the man who had remained frozen in their memory as their 29-year-old teacher. Ray spoke to him directly: “Thank you for what you did for us.”

Only later in the evening, when they gathered for beers at a bar in their old neighborhood of Northwest Hills, did someone ask the question that was on all of their minds: Has anybody heard from John?

Ray listened to the others recite the latest reports about their former classmate, the shooter, John Christian, the son of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s former press secretary George Christian: He lives a few blocks from here. He’s practicing law. Someone saw him recently. What do people say about him? Is he . . . normal? For Ray’s part, the last he had seen of John was when his friend had disappeared into the back seat of a police car. Yet John continued to hover over his life like a spectral question mark, both inexplicable and utterly familiar. “He wasn’t some monster you could easily explain away,” Ray said later. “Hell, he was one of us.”

Ray spent the rest of the evening at the home of a former classmate who’d settled in Northwest Hills. The two of them spoke late into the night, and their conversation resumed the next morning. Talking about it lessened the burden. Still, there were so many questions about the shooting for which they had no answers.

Later, Ray went outside and pulled his bicycle from his Honda. Cycling had become one of his preferred forms of therapy, and he went for a long ride that day, south to Barton Springs. There, he floated in the cold, clear water, feeling momentarily light.

The Austin of 1978 was a smaller, simpler city, contentedly lacking in renown. Back then, houses were affordable, traffic manageable. It was also the case that an adolescent boy could, in broad daylight, during the morning rush hour, walk along a suburban street and down a grassy hill to school carrying a Browning .22-caliber rifle and nobody would think to stop him. School shootings were not a concern then. Not in Austin. Not anywhere.

The 1978 killing of Rod Grayson wasn’t the first murderous intrusion into the sanctity of America’s schools. It did not plunge the entire city into terror the way Charles Whitman’s rampage from the University of Texas Tower had twelve years earlier. Nor did it match in sheer bloodshed the later infamy bestowed upon campuses that we now recite as a mournful litany: Columbine. Virginia Tech. Sandy Hook. Marjory Stoneman Douglas. Umpqua. Santa Fe.

Yet to those who experienced the shooting at Murchison Junior High School, it remains, even after four decades, mercilessly unforgettable. This is particularly true for the 21 witnesses of the shooting, 8 of whom I spoke with; for Rod Grayson’s widow, Laura, whom I also interviewed; and for the killer, John Christian, who did not respond to repeated interview requests.

The anguish that has plagued the Murchison students presages the kind of long-tail trauma that many of today’s witnesses to shootings will be burdened with for the rest of their lives. According to the Washington Post, more than 240,000 U.S. students have experienced a school shooting since 1999.

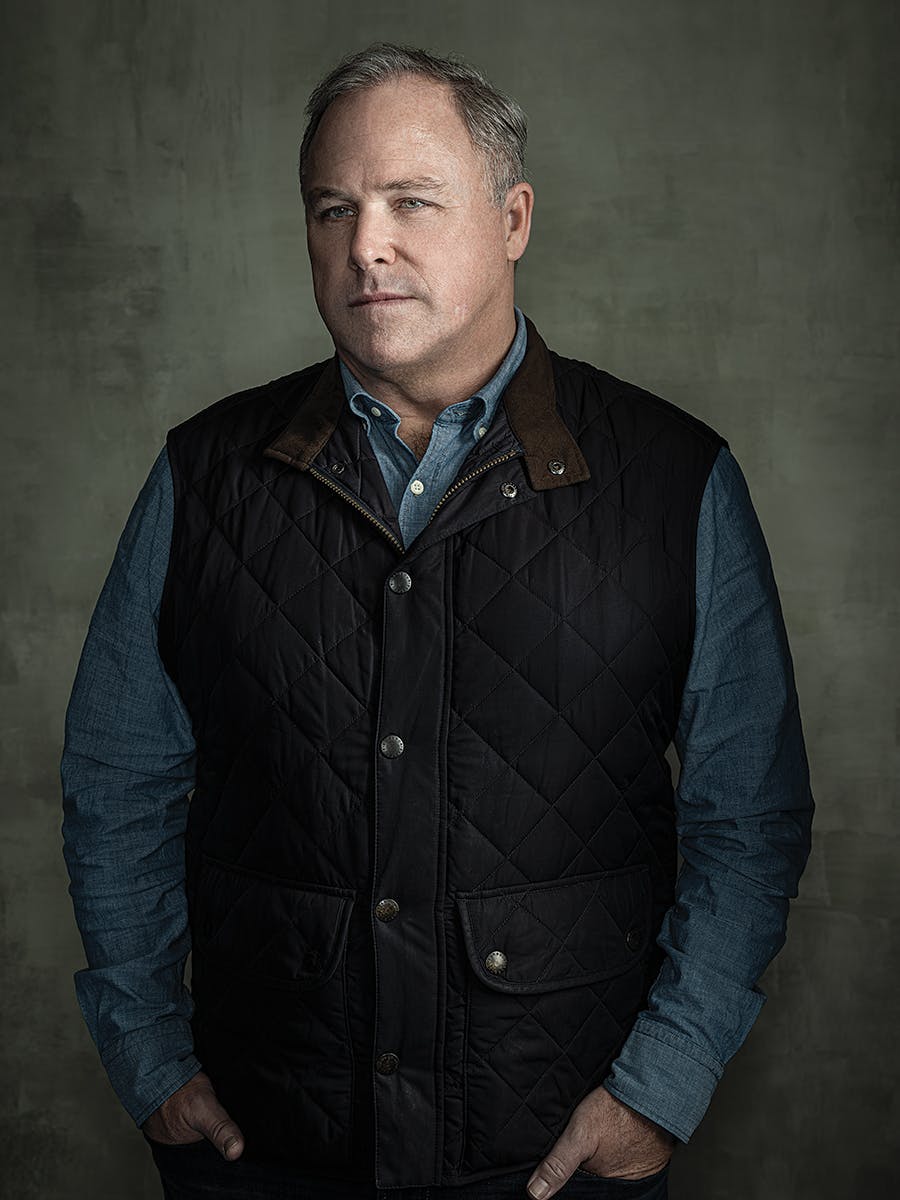

But no school shooting is quite the same. Peculiarities form the contours of the Murchison shooting. For one, there is the trajectory of John Christian: from gifted student to teenage killer to middle-aged tax attorney quietly working and living in Austin today. There is also the manner in which the collateral victims were dealt with—or, more precisely, not dealt with. Many of the details surrounding the incident and its aftermath have gone unreported, leaving the victims with unanswered questions that have derailed their own attempts at recovery. “It’s all just speculation,” Peyton Smith, one of the students present in that classroom, told me in his Austin law office last September. “So as a result, I just have to process what I’ve got. You look at the jigsaw puzzle, and there are huge pieces that are not there.”

Thinking back to that distant morning, Smith began to describe his proximity to his teacher; he had been the nearest student to Grayson when the shooting began. Then, as we spoke, he started to cry. “Lives were shattered,” Smith said. “Lives were changed. Every person in that room was a victim.”

I used to have a recurring dream that I was surrounded by people who seemed to think everything is fine, and I was trying to tell them that it isn’t.

—Rebecca Leamon, student of Grayson’s

When Rod Grayson interviewed on June 20, 1977, for the job of teaching the gifted and talented students of Murchison Junior High, he was an unemployed 28-year-old. His wife, Laura, herself a teacher at Austin’s LBJ High School, had given birth to their son, Ian, earlier that day. Unlike his father—an employee at Humble Oil who at first had not approved of Rod’s marriage to a Mexican American—he was a free spirit who wrote poetry, smoked marijuana, and had ambitions of becoming a professional actor. But Laura’s pregnancy had scuttled such notions, and he went looking for a steady paycheck. After getting his teaching certificate, he had applied for the Murchison opening. The pilot program’s coordinator, Marilyn Eichenbaum (now DuVon), saw his potential right away. “Even though he had no experience teaching, I could tell he would provide the right fodder for these kids,” she said. “He was this strapping young man with a keen mind and great energy.”

Nearly all the students Grayson taught during what would be his only two semesters as a full-time educator lived in the neighborhood of Northwest Hills. Situated at what was, back then, the northern edge of the city, the neighborhood was populated with doctors, bankers, professors, restaurateurs, and pastors. Murchison’s student body was overwhelmingly white and socioeconomically privileged. Twenty-nine children were handpicked for Eichenbaum’s and Grayson’s classes. These students were deemed exceptional not because they had high grades but because they seemed to possess a certain creative spark.

Whatever his earlier aspirations had been, Grayson found his calling as the Pied Piper to these brainy adolescents. Sitting on a stool, he would begin class with a meditation exercise. Then he would instruct his students to write a free-form essay or short story based on a poem he would read aloud or a curious drawing he had sketched on the blackboard. He was demanding. Susie Gerrie Davis remembers his insisting on several revisions for a written assignment, telling her, “I think you could do something pretty important with this gift of yours, and that’s why I’m requiring so much work from you.” (Davis has since become the author of several faith-based books.) Two other students turned in a project that Grayson considered sloppy, and “he ripped our shit apart,” one of them recalled. “Which was crushing but also fantastic. He had super-high standards.”

At the same time, the handsome and witty young teacher (“I think every girl had a crush on him, including me,” said one student) was an attentive, empathic big-brother figure. Rebecca Leamon remembered how Grayson gently encouraged her to challenge her shyness. Logan Bazar recalled how the teacher regularly let him out of class five minutes early so that he could avoid being jumped by two bullies. And Andre Terry, one of Murchison’s few African American students, who was bused to school from the East Side, would one day credit his junior high school teacher for pushing him to follow his artistic impulses and become a fashion designer.

“He was like no other teacher I ever had,” Terry said. “He was a friend.”

Though Grayson resisted playing favorites, he became especially close with one student in particular who shared his love of stage acting: John Christian.

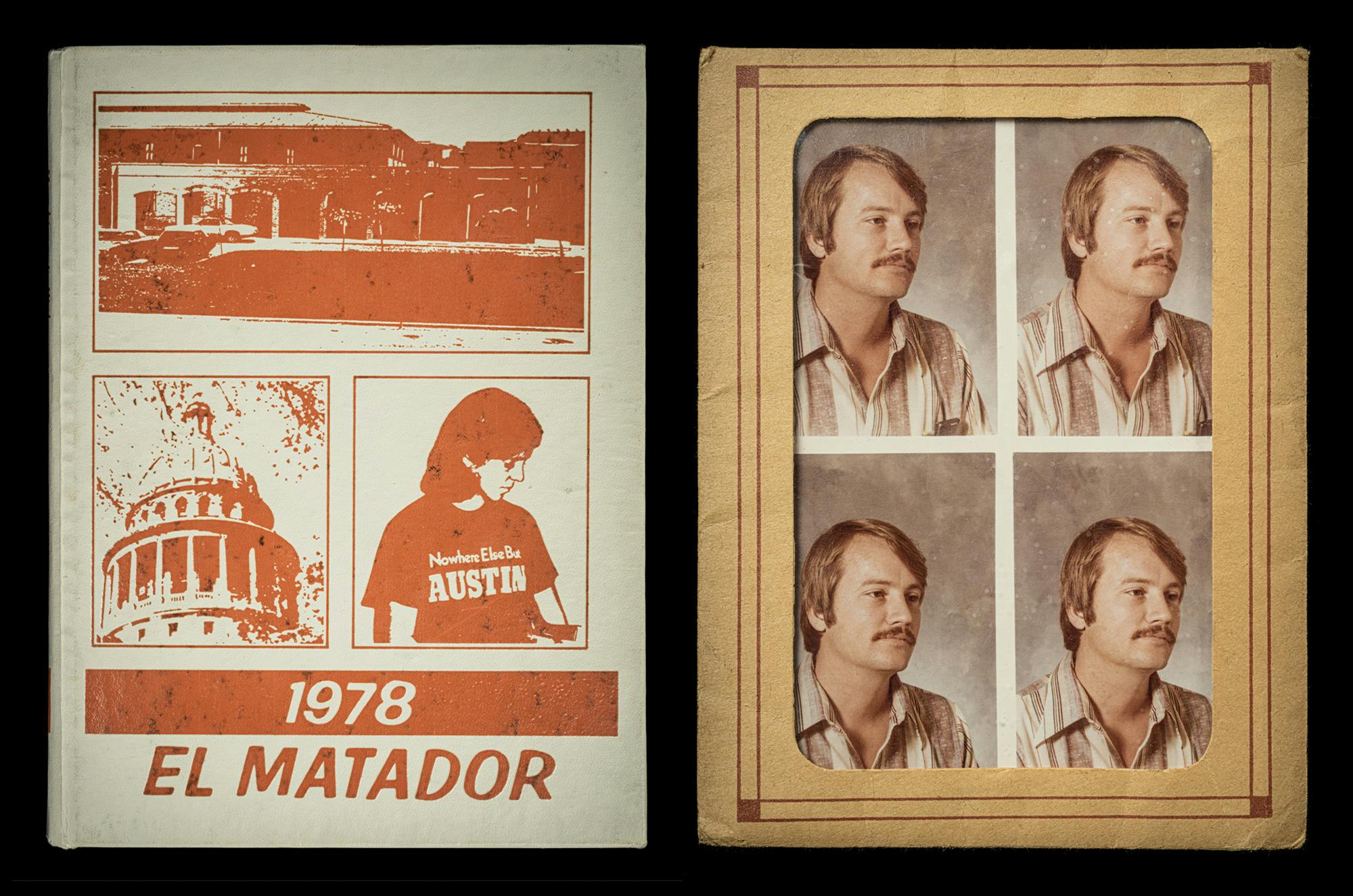

If there was a Murchison student destined for great things, it was John. According to his classmates, he was “the smartest one in the whole group,” “a great student and a really good artist” with a wry wit who drew “political cartoons that could have been in any newspaper.” His preternatural maturity meant that “he always got cast as the older person in the school plays,” and “he dressed like a grown-up” (often in striped short-sleeved shirts and crisp slacks). Though the tall, slender, floppy-haired boy seldom spoke up in class except to correct someone else’s error, John seemed immune to the self-doubt that consumed his peers.

“Everyone knew John—he cut a figure,” said Logan Bazar, one of his closest friends at Murchison. “John and I bonded on the soccer field. We played backfield a lot because we were both bad. We hung back and prayed the ball didn’t come our way. That gave us some time to talk. I felt lucky that he found any interest in me, because he was so much smarter and worldlier. We were all interested in women, but he wasn’t the uninformed idiot I was. He’d read Erica Jong and told me that it took women seven minutes to reach orgasm. He’d done some reading on Hitler and the Nazis, which wasn’t uncommon for boys our age. He took the time to learn things.”

Then there was John’s pedigree. His father was George Christian, a legendary figure in Texas politics who had served as President Johnson’s press secretary and later became a top adviser to Governor Dolph Briscoe. John’s mom, Jo Anne, was an accomplished lawyer and patron of Austin’s arts scene. John was the third of their four sons (George had two adult daughters from a previous marriage). The family occupied a sprawling house on Rockledge Cove, a short walk from the Murchison campus, with an enormous magnolia tree in the front yard that had grown from a sapling given to them by Lady Bird Johnson. The Christians weren’t rich by Texas standards, but they had forged elaborate social and professional ties to power brokers and superachievers that extended well beyond Texas. Of course, few Murchison students paid much attention to such distinctions. Nor was it the habit of adolescents to speculate on anyone’s psychological burdens apart from their own—unless, that is, they were confided in, as Bazar was by John.

“His dad was the main topic of conversation,” said Bazar. “I would remember this even if nothing had happened, because it was a constant theme in John’s life, the pressure he felt from his dad and the absolute lack of grace it seemed that he lived with. I think John had reached a point where he was never going to be good enough. And that year, he was growing more and more bitter about his father.”

In reality, George and Jo Anne—“both of them smart, stubborn, and overextended from all their obligations,” according to John’s older brother George Scott—were likelier to be distracted parents than dictatorial ones. Both were busy during all hours of the day. At night, according to George Scott, they sometimes argued heatedly. Their father “didn’t have that much emotional range. He was always either kind of happy or kind of pissed.” Even in his more upbeat moments, recalled the elder son, George was an emotionally distant patriarch—one who, like most men of his generation, avoided talking about feelings or the traumas of his own youth, such as the death of George’s father when he was quite young. Above all, after years on the government payroll, George had a private political consulting business to run. And while George Scott recalled his own childhood with fondness, John’s experience might well have been different.

The origins of John’s mental illness are unknowable. Two years before the shooting, a sixth grade classmate noticed that John had sketched a scene of a mass shooting, with red flames leaping out of the gun. At one point in eighth grade, he urged a female classmate to play a game with him: there was someone on the school pay phone John wanted her to talk to, a man who was threatening to jump from the top of a skyscraper. The man’s initials were “J. C.” Playing along, the girl picked up the phone and spoke a few reassuring words to the nonexistent person on the other end. John thanked her, saying that the man named J. C. was comforted by what she said.

A few weeks before the shooting, Grayson was at home grading papers when he handed one of them to his wife and said, “Tell me what you think about this.” It was a short story written by John. Laura gazed at it in disbelief. The story, written in unsparingly graphic language, was about robots that prowled the streets and castrated men.

She handed back the paper, slack-jawed. Her husband nodded and offered a sad smile. He’d been concerned about John. “His parents expect a lot from him,” he said.

Ever since then, whenever I walk into an unfamiliar place, I’m always looking for a way out. Because I was in the back of the classroom. I felt trapped.

—Elaine Moore, student of Grayson’s

The tragedy was set in motion by happenstance. The morning before, on May 17, 1978, Rod and Laura Grayson noticed that Ian was running a fever. It was Rod’s turn to stay home with the baby, so he called Murchison and requested a substitute teacher for his classes, beginning with GT English. The agenda for that day had already been set. Two of the students, John Christian and John Ray, would be giving an oral presentation of a chapter from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s classic novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

To the astonishment of his classmates, the normally reserved John Christian proceeded to enter an alternate universe that bore no relationship to Stowe’s novel. He began hollering loudly, profanely. He flung his arms about and jumped several times in the air. He said something about the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. He whirled to the chalkboard and drew a couple in bed together—and then, whirling back to face the room, said, “Whoever can make the ssssssssss sound the longest can win this piece of chalk!”

The class erupted in raucous laughter. John, their quiet resident genius, had come out of his shell! Meanwhile, the substitute teacher glowered and scribbled away in his notebook. After the bell rang, Ray—who had stood helplessly off to the side while his classmate went on his manic riff—muttered, “John, when Mr. Grayson hears about this, he’s gonna kick our butts.”

“Don’t worry,” John replied. “I’m going to bring a gun tomorrow.”

He wasn’t laughing. Still, it had to be a joke, Ray thought. “Yeah, yeah—I’m gonna bring one too!” Ray exclaimed. The two of them then walked across the hall into the classroom of Eichenbaum, who recalled, “John went directly from that substitute teacher to me, and there was nothing at all memorable about his behavior.”

But two other things happened that might have signaled John’s downward spiral. That same day, John reportedly destroyed a map he had designed for a school assignment. (Psychiatrists later testified at his trial that he had begun to take pleasure in succumbing to violent impulses.) That afternoon, his math teacher, Anita Sybesma, reminded him that he was doing poorly in algebra. She warned him that he needed to study hard for the upcoming test. “If you don’t pass it,” she said, “you’ll fail the class.” The prospect of failure loomed.

The next morning, while the rest of his family filed out the front door to their respective daily destinations, John stayed behind, hiding in a closet. When they were gone, he stepped out into the empty house. According to psychiatrists who questioned him later, he contemplated killing himself with the Browning .22-caliber hunting rifle that his parents had given him for Christmas. Instead, without any sort of plan, he walked outside, across the lawn, under the canopy of oaks and the great magnolia tree, and onto the sidewalk. It was a curious spectacle, one that Americans had not yet come to dread: a young white man with a firearm.

Class had already started without him. What transpired next is based on the recollections of eight eyewitnesses in the classroom as well as those of others at school that day. Sitting, as he always did, not behind his desk but on his stool directly in front of them, Grayson had begun by asking his students what the hell had happened the previous day. They glumly acknowledged their own misbehavior. They added, But Mr. Grayson, John was acting so weird!

The teacher waved them off. “You just don’t understand him the way I do,” he said. Then: “Where is John, anyway?”

“There he is!” someone exclaimed, directing their attention to a figure outside the classroom window who was heading down the grassy hill beside the football field.

“And,” someone else said, “he’s got a gun!”

What occurred in the next two minutes would be remembered through trauma’s kaleidoscope. But as all the eyewitnesses I spoke with took pains to explain, the sight of John with a hunting rifle was a momentarily bemusing one. It’s a skit! John and Mr. Grayson planned all this! This is going to be great!

John stepped into the doorway. Seeing him, Grayson may have smiled, may even have laughed. “Okay, John. Joke’s over.”

John held the gun at his hip, pointed at his teacher. A classmate heard him say, “The joke’s on you.”

He shot Grayson three times, in the arm, chest, and forehead. Grayson fell from his stool and collided with the student desk in front of him, where Peyton Smith sat. Then his tall, lean body thudded heavily to the floor.

The next sound might well have been unsteady applause, since many if not most of the students were still convinced that they had witnessed an exquisitely executed dramatic performance. But the puff of gun smoke prompted Smith to look more closely at his teacher. Blood poured out of one of his ears. His eyes were wide open. He looked terrified.

As John turned and walked out without another word, the classroom exploded into screams. Smith was the first one out the door. He ran to the principal’s office and told the administrators at the front desk what had just happened. No one seemed to believe him. Then, for the first time in his life, Smith—whose father, Ralph Smith, was the pastor at Hyde Park Baptist Church—yelled out the Lord’s name in vain: “Goddammit, he killed him!”

Eichenbaum was outside the office when she heard the screams from the classroom and at first laughed to herself: Oh, Lord. What’s Rod got his kids doing now? Then they were clinging to her, sobbing hysterically. She led several of them into a nurse’s examination room and told them to stay there.

Gym class had been underway outside by the football field. A few kids saw John toss the firearm against the bicycle rack and then run up the slope. Coach Larry Schirpik saw this as well. His knee was healing from surgery, so he ambled to his truck and gave chase. He caught up to John at the top of the hill. Jumping out of his truck and grabbing the boy, Schirpik barked, “What did you do?”

“I shot Mr. Grayson,” John said.

Schirpik drove him back to school and led him by his arm into the principal’s office.

Jo Anne Christian materialized in the administrative office, her palms flat on the counter, as she demanded, “Where’s John?” Soon, the Austin police arrived. The local media began to swarm the school as well. They shouted out questions as Grayson’s students were herded into a school bus that would take them to police headquarters to be interviewed. Some of the students extended their middle fingers to the press in hopes of stopping them from taking pictures. As the bus pulled away, one of them noticed other Murchison students in their classrooms, faces pressed against the windows, staring. On the way to the police station, someone spontaneously led the group in singing church hymns.

John’s older brother George Scott was pulled from class at his high school and instructed to drive home. Passing by Murchison on the way, he saw his father walking hurriedly downhill to the school. The look on George’s face was a devastating sight, the son would one day write in an autobiographical essay: “At that moment the veneer of the public figure had been stripped away, exposing the anguished soul of a father whose son had cried out for help in an unspeakably violent and destructive act.”

John was led out of the school building by police, and he hid his face from the cameras. After seeing his son whisked off in a squad car, George headed to the police station. There, a reporter saw him sitting on a bench, “visibly shaken.” Eventually, he went home, where several friends and family members met him. James Neff, a reporter from the Austin American-Statesman, rang the doorbell. The former press secretary told the reporter that his son “got the weapon here at the house, I guess. I don’t know.” He also said, “I don’t want to say anything that might hurt my boy.”

George asked Neff about the schoolteacher who had been shot. Did he have a family? When Neff replied that Grayson and his wife had an eleven-month-old son, the reporter watched as something seemed to collapse inside the father.

Meanwhile, Laura Grayson arrived at Brackenridge Hospital. A gurney rolled past her, a sheet pulled over the body. But she could see Rod’s cowboy boots poking out. He had been so proud of those stupid things—she never understood why.

Back at the police station, Grayson’s students were ushered into a room where investigators asked each of them questions. The children, though, had questions of their own, above all: Is Mr. Grayson okay? They weren’t told anything. Some of them, assuming he had survived, were hoping to visit their teacher in the hospital. One overheard a cop tell another, “He didn’t make it.”

On the drive back home, Susie Gerrie Davis learned from her mother that Grayson had died. She screamed and contemplated throwing herself out of the car, onto the highway. Logan Bazar, who hadn’t been present during the shooting, was dispatched to Grayson’s classroom to retrieve his personal effects. He could see that someone had tried to wipe away the blood, but traces remained. John Ray came home to a shattering quiet. Seared into his brain were two images: his friend John walking into the classroom with a rifle in his hand and his teacher lying on the ground in a pool of blood. He asked himself, What now?

That evening at the Grayson home, a teacher friend stood on the front lawn and handled all the visiting reporters. At some point, one of Rod’s brothers began looking through his papers, and he happened to pick up the disturbing story John had written about the castrating robots. He brought it to Laura, who threw it away. As she would later say, “At that point, as a mother, as a teacher, as a human being, as pained as I was that Rod was dead, I felt sorry for that kid. I didn’t want that story to get out.”

Wow. Man. I’m just now remembering. I had this recurring dream. It started after the shooting. That movie Dawn of the Dead had just come out. I dreamed that John Christian was leading this big group of zombies from the projects near where I lived. They’d come over the hill and kill everyone around me. . . . You know, I consider myself to be a pretty strong-minded person. But after talking about all this, I’ve been in a very weird state of mind. I can’t really describe it.

—Andre Terry, student of Grayson’s

A few days after the shooting, Bazar visited his friend at the Gardner Betts juvenile detention facility, in South Austin.

“Can you believe it?” John asked, referring to the shoelaces and belt that the authorities had taken from him for fear that he might attempt suicide. The two boys sat in the cafeteria. John seemed caustic and above it all—qualities that Bazar had, under very different circumstances, once found attractive. During their half-hour conversation, John took issue with a report in the media that he had said “The joke’s on you” before shooting Grayson.

“There were only two people close enough to hear what I said,” John remarked. “And one of them isn’t talking.”

For years, Bazar would be haunted by this conversation. Why did John seem so unaffected?

No one, including the Christian family, was disputing that he had intentionally killed Grayson. Still, as a juvenile, he could not be charged with murder and tried as an adult. The worst John could expect—under state juvenile laws that would be toughened during the nineties—was to be judged guilty of delinquent conduct and confined to a Texas Youth Commission facility until he turned eighteen. The new Travis County district attorney, Ronald Earle, publicly announced that he intended to seek the five-year maximum “if the boy is found sane.” Though juvenile trials are not typically open to the media, an exception was made in this case (those with firsthand knowledge of why an exception was made have died, declined to be interviewed, or simply cannot recall).

The Christians hired the city’s most prominent criminal defense attorney, Roy Minton. John’s fate rested in the hands of state district judge Hume Cofer, a by-the-book jurist who was not regarded as a softie. Austin was a small town in those days, so it was no surprise that Judge Cofer, like George Christian, had an LBJ connection: his father had been Johnson’s attorney following his scandal-ridden 1948 U.S. Senate race.

There was another connection that wasn’t reported at the time. Earlier that same year Minton had managed to get a drug charge thrown out against Cofer’s estranged son. (It’s not clear whether Earle was aware that Minton had previously represented Judge Cofer’s son. Earle has been ill for some time, according to his wife, Twila, who spoke to me on his behalf. Reached by phone, Earle’s assistant district attorney Jacqueline Strashun could not recall for sure if Cofer, who died in 2016, had disclosed the association but added, “Judge Cofer was a very, very straight guy, probably the most ethical judge at that time.”)

Minton hired two psychiatrists to evaluate John and supply expert testimony. One of them, Daniel Matthews, has since been recognized as a pioneer in the therapeutic treatment of pathologically violent juveniles. The other, Richard Coons, was one of the state’s most prominent psychiatric experts at criminal trials, one whose judgments often resulted in murder defendants’ being sent to death row. Like many Austin professionals, he knew the Christians socially.

On June 2, 1978, two weeks after the shooting, John sat outside a small courtroom at Gardner Betts while the two psychiatrists testified inside to Judge Cofer that John was “acutely depressed” and suffered from “latent schizophrenia”—the latter being an inexact, catchall term that would eventually fall out of favor in the psychiatric community. (When I spoke with Coons recently, he told me, “My feeling overwhelmingly was that he was depressed.”) The prosecution did not contest the recommendation by Coons and Matthews that John receive treatment rather than incarceration. And Cofer concurred with Minton’s two experts. He ordered that John be remanded to the care of the Timberlawn Psychiatric Hospital—a private facility in Dallas for which the Christians would be paying the bills—until his eighteenth birthday or until he had recovered.

On Monday, June 5, 1978, Jo Anne and George flew with their son and a probation officer to Dallas, where John reported to Timberlawn.

Sept. 17, 1979, Mon. 5:37 pm

Dear Elaine,

It was really neat to hear from you. I have not seen you in a long time. I’ve been up here now for a year and three months, some of which has been real hell, the rest of which has really been good. I have definitely changed a lot since I came here, and it has been a really good feeling to change this way. I haven’t heard from you, so I don’t really know what to write. The music I’m into is the Doobie Brothers, Moody Blues, Pablo Cruise, Queen, Simon & Garfunkel, the Little River Band, and The Doors—plus another hundred like Santana, Kansas, Styx, Chicago, and Boston who I think are good. I heard from Katie and now from you that you’re now a Disco Queen. More power to you; the moves you made at the Valentine Dance in 1977 were impressive enough. I still only slow dance, because I’m not too rhythmic. It doesn’t take any effort to stand in one spot and go in circles.

Write soon,

Love, John

—Letter to former classmate Elaine Moore, from Timberlawn

It is a cornerstone of civilized societies that sharp legal distinctions are drawn between children and adults. And it is a medical fact that the adolescent brain is far from fully developed—which means, among other things, that a violent youth, even a murderous one, is not inexorably destined to a life of brutal criminality. That’s especially true when no resources are spared to treat a violent adolescent, as was the case with John Christian.

Timberlawn, which opened in 1917, was a national model for inpatient treatment during the time of John’s residency. The population of 150 or so residents included about thirty juveniles, of whom no more than sixteen in John’s age range were housed in a separate dormitory. The institution offered a full academic curriculum as well as a rigorous daily regimen of group and individual therapy with multiple mental health professionals. As Dr. Jerry Lewis III, who worked at Timberlawn from 1982 to 1994 and whose father was the chief psychiatrist during John’s stay, put it, “The idea was to not just use behavior modification to change a boy’s aggressive antisocial behavior but also to use psychotherapy to get him to appreciate the fact that his behaviors are attempts to ward off deep and painful feelings. So for eighteen months or thereabouts, you have them confront their defense mechanisms and talk about their core issues. As they work through their core issues, it changes the driving forces behind their behavior.” That approach began to recede during the nineties, as Texas and other states moved toward cheaper and harsher measures to deal with juvenile violence. (Timberlawn was closed in early 2018.)

John had been at Timberlawn for twenty months when a representative of the Christian family returned to Judge Cofer’s courtroom. The representative requested that the original order to institutionalize his client be modified. The Christians asked that their son be permitted to visit Timberlawn on an outpatient basis. They proposed that the boy live with an unnamed physician in Dallas, who would become John’s legal guardian. On February 19, 1980, the judge granted the request. The decision was not made public.

Nearly a month passed before Statesman reporter Guillermo Garcia was tipped off that John had moved in with a Dallas family. He began making inquiries. George agreed to meet Garcia at his office on the eighteenth floor of the American Bank tower, in downtown Austin. The former press secretary declined to supply information about whom his son was living with or how the determination had been made that John should be treated on an outpatient basis. He did tell Garcia that his son “had to remain in Dallas for treatment and we are, of course, not living there.” Garcia also spoke to someone he described as being “familiar with the case” who told him that Timberlawn psychiatrists “felt that to continue the on-site care would effect a regression” in the boy’s mental health. Though George did not want the Statesman to publish Garcia’s story—and, indeed, a few people representing the Christians had paid a visit to then–editor in chief Ray Mariotti to express that very sentiment—his posture was anything but belligerent. To Garcia’s surprise, the typically stoic father broke down in tears.

“If I’d just done more for John earlier, been around more,” George said quietly.

Garcia’s story ran in the Statesman anyway. What remained unreported until now was the identity of the man who had become John’s adoptive father. He was a Dallas eye doctor named John Eisenlohr, who was a prominent member (and later the president) of the Texas Ophthalmological Association, a group whose lobbyist was George Christian.

Eisenlohr’s children attended Highland Park High School, in the affluent community where John would spend the next two and a half years. He enrolled at Highland Park High in the middle of his sophomore year. Rumors swirled around the quiet new student. One of his new classmates came across a newspaper story that identified John by name and described him as “schizophrenic.” The classmate wondered, Why is he at our school?

Those concerns subsided over time. John returned to his passion, drama, and also became the news editor of the school paper, the Bagpipe. (A Dallas friend of George’s wrote him to say that her daughter worked on the staff of the Bagpipe and “has mentioned how much she admires the work John did and how intelligent he is.”) The Dallas media left John alone. So did the Austin press.

John graduated from high school on schedule, in May of 1982. That summer, he returned to the city of his youth and enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin.

A few weeks after the shooting, John’s classmates graduated from Murchison. The following school year, they were bused to different high schools. They had spent the previous two years together, and their abrupt separation constituted a kind of loss unto itself. Who could possibly relate to their experience? “You didn’t know what to do with all the emotions,” John Ray recalled. “The message was ‘Move on, move on.’ ”

So the Murchison kids tried to move on. For Ray, it was as if the next few years were completely erased. His Murchison friends were gone. His parents divorced. At sixteen, he began to drink heavily. His driver’s license was suspended after he racked up speeding tickets. Austin felt strangely unsafe to him, even aside from willful recklessness. He toggled between hedonism and religion, each in zealous doses.

Ray was among several Murchison alumni who went on to UT. There, they began to see John Christian on campus. It was jarring. Without ever consciously coming to this conclusion, most of the Murchison kids presumed that they had suffered two losses on May 18, 1978—their beloved teacher and their promising classmate. Few, if any, had considered the possibility that John might reappear in their midst. And they learned of his reentry into their world not through any notice from authorities but instead through word of mouth and random encounters.

One former classmate, Cathy Olson Muth, was home from college, eating with her family and friends at a restaurant in Northwest Hills, when she happened to see a familiar reflection in a mirror. “John Christian is sitting right behind me,” she whispered to her mother.

Wow, she thought. He’s back in the neighborhood. Nothing is ever gonna happen to that guy.

Another Murchison student, David Mider, ran into John at the Texas Tavern, in the UT student union, and learned that the boy who had killed one of Mider’s favorite teachers was now studying at UT. How am I supposed to process that? Mider wondered. (John went on to study at the university’s prestigious law school. The State Bar of Texas requires law students to disclose only current character issues and mental illnesses, not past ones.)

In 1990, Susie Gerrie Davis was living in Fort Worth and reading a book at home while her two young children napped when she inexplicably started to cry. Then the images resurfaced out of nowhere. The boy with a gun. The teacher on the floor. Blood gushing. The noises: the gunshots, the screams, the scraping of chairs. And then, as Davis would write in her 2015 book Unafraid, “I could smell everything. Gunpowder. Pencils. Chalk dust. The perfume I sprayed on my T-shirt that day.”

Later, she began sharing her trauma with a small group of Christian women. Bit by bit, she recalled panic attacks she’d experienced in high school, moments of jogging past John’s house in Northwest Hills and being afraid that he might see her. As Davis recalled in Unafraid, until fully accepting God’s love and the injunction of forgiveness that came with it, “I figured John had wrecked my life at fourteen. He walked in with that rifle and blew away my childhood, my sense of safety, and my hope for a happily ever after.”

In 1993, soon after she and her family returned to Austin, Davis was shopping for breakfast cereal at a grocery store in Northwest Hills with her four-year-old daughter when she heard someone say, “Hi, Susie. How are you doing?”

It was John. Hugging her daughter close and wanting to scream, Davis carried on a banal conversation about his job and about her church. It was only after she got her daughter into the car that she began to sob. Then she prayed to God for grace toward John. Slowly, she could feel compassion seep in.

At a charity gala in downtown Austin in 1992, Peyton Smith—by then a 28-year-old attorney—looked across the dance floor to see a smiling and tuxedo-clad John coming his way. John hugged him. “It’s so good to see you,” exclaimed the classmate Smith had last seen with a hunting rifle in his hands.

John attempted to make small talk, but Smith abruptly cut him off and told him that he owed a visit to someone else. Walking away, Smith felt a sense of disgust. Unlike his old friend Davis, who had been swallowed up by fear and then moved by her faith toward forgiveness, the boy who had been closest to the line of fire that morning had since carried himself with a sense of imperviousness.

But he had yet to make peace with the incident. As he would write on the Facebook group that Ray dedicated to Grayson, “That moment is still as raw and real and technicolor today as forty years ago.”

Ray, in the meantime, had continued to spend his post-Murchison years in a state of what he would tactfully term “self-anesthetizing.” A wayward path took him to Central America, where he was inspired to later attend seminary and become a spiritual director—essentially a roving ordained minister gravitating to those who had experienced trauma. But Ray had not so much as acknowledged his own emotional scar tissue until one morning in April 1999, when he was driving through the University of Arkansas campus and heard on the radio about the mass shooting at Columbine High School. Suddenly, he thought he saw a jumbo jet nosediving into Razorback Stadium. He pulled over to the side of the road, awaiting a fiery explosion. But it never came. The hallucination portended something. Something in his psyche began to crack open.

A few days later, Ray drove twelve hours northwest to Littleton, Colorado. Rolling past the high school, wandering through the memorial sites and services, Ray felt curiously at home with the grieving, as if his own trauma had been given permission to voice itself. “It all felt surreal,” Ray said. “Twenty years overdue. I don’t remember talking to anyone specifically. I think it was all I could do just to be there.”

Ray called his old classmate Susie Gerrie Davis, who happened to be in Colorado on vacation. They met up for the first time in years to talk about the grief they’d carried for two decades. Davis later called their former teacher Marilyn Eichenbaum DuVon, who then reconnected with other former students who were in Grayson’s classroom that day. They were among the many Murchison alumni who would later recall the Columbine tragedy as a moment when they felt engulfed by their own past and became, in effect, witnesses again to the loss of their innocence.

Ten years later, in 2009, Ray’s youngest daughter, Olivia, who was ten years old, was struck by a Cadillac Escalade and killed at a street crossing on Razorback Road while her sister Hannah watched. The driver of the Escalade was a well-to-do lawyer’s son who hailed from Highland Park and who was attending the University of Arkansas. Ray’s pro bono lawyer was outmatched by the legal team assembled by the young driver’s father. Faced with a protracted battle—and not wanting to see a young person suffer for something he hadn’t intended to do—Ray and his wife ultimately chose not to pursue civil litigation.

His daughter’s death did not make Ray angry at God. But he found plenty of fault with God’s creatures. He couldn’t fathom how the world continued to carry on while an innocent girl lay buried, and how quickly some young men were issued reprieves. Still, the fury was as oppressive as the grief. “Then came the deep work—the ‘Okay, what do I do with this? How do I deal with it?’ ” he recalled. “Reading, praying, counseling. It peeled back all the layers. And beneath all the destructive behavior and armoring up emotionally, there was that one event.”

Ray recounted all this while sitting on the patio of a South Austin coffeehouse one morning this past September. He had a notebook in front of him that he had been filling with random musings. The notes were the beginning of a book manuscript that a literary agent was urging him to write. Its tentative title is “A Field Guide to Grief.”

It was my first face-to-face meeting with Ray. But our initial conversation had been twenty years earlier, just after the Columbine High School massacre. He was trying to get in touch with a former classmate, Rob Draper, who he’d heard had just published a novel. Ray looked me up—and, yes, I had just published my first novel. But no, I wasn’t the Rob Draper who had gone to Murchison. Still, Ray kept talking. Within minutes, I was learning for the first time about the shooting on May 18, 1978.

Like most Austin journalists, I knew George Christian as a towering, back-slapping eminence. It struck me as odd that I had never heard about his son’s having killed a schoolteacher, particularly since I had been a staff writer at Texas Monthly for most of the nineties. After speaking to Ray in 1999, I wrote John Christian a letter to see if he would be willing to share his story in GQ, where I was working at the time. A few days later, my phone rang. It was George. “John won’t talk to you. None of us will talk to you,” he said. “And if you publish this story, it will destroy our family.”

My editor at GQ ultimately decided the story would not work without the shooter’s participation. In the ensuing years, I gave little thought to the Austin tragedy. George died of lung cancer in 2002, and Jo Anne died in 2015. Then, on May 18, 2018, I received an email from a Washington, D.C.–based journalist named David Nather, whom I had never met. The subject line was “Question for you—Murchison shooting.” Nather, as it turned out, had attended Murchison in 1978 and had been outside during gym class when John emerged from the school entrance with a rifle in his hand. He had heard from Ray that I had looked into the story and was curious why I had dropped it. The shooting was on Nather’s mind, he wrote in the email, because that day marked its fortieth anniversary—a fact that he might have forgotten but for the reminder he received courtesy of the morning’s horrific body count at Santa Fe High School. “Even for those of us who weren’t in the classroom, there is a chilling kind of flashback that happens with every school shooting,” he wrote me.

Like others who had experienced the Murchison shooting, Nather remained perplexed by the aftermath: the swiftness of the court proceedings, the secrecy that attended John’s road to recovery, and the seeming normalcy of his adult life. Everything was a gnawing mystery. In Nather’s view, the recognition that so many lives were deeply affected by the shooting was proof that such a story needed to be written. What had kept him from writing it himself was that he hated the thought of bringing anguish to his former classmate John Christian.

I heard that sentiment expressed by nearly all his Murchison classmates. They do not bear John any ill will. Still, none of them understand what drove him to kill the teacher he seemed to love as much as they did. Given that no one had ever explained anything about John’s treatment and release from custody, some worried that he might still be capable of committing a violent act. Even those who believed him to be harmless couldn’t help but be bothered by the soft landing he seemed to have been accorded.

The family’s position, which has remained unchanged over the years, is that a thirteen-year-old boy fell into a deep, perhaps psychotic state of depression and committed a terrible misdeed. As a juvenile, he was entitled to anonymity. But because his father was a public figure, the boy’s identity was splashed across the front pages. He received intensive psychiatric treatment, was deemed by professionals to pose no threat of further violence, and was released to live a quiet and productive life. He has done all the system has asked of him. No more need be asked or should be asked, especially after the passage of so many years.

Of course, juveniles are often named by the media in cases involving murder. And though sentencing laws vary widely across the country and have evolved over time, the system has historically tended to ask a great deal more of juvenile killers. In 1984 the system asked 12 years in prison of a fifteen-year-old Colorado boy named Jason Rocha, who suffered from depression but had committed no prior acts of violence before he shot his thirteen-year-old friend to death. In 1988 the system assigned 206 years in prison to a Montana boy named Kristofer Hans who, as a fourteen-year-old, had murdered a teacher and wounded three others after he received a failing grade. In 1992 Texas sentenced Edwin Debrow to 27 years for killing a cab driver during an attempted robbery—despite the fact that the twelve-year-old was too young to stand trial as an adult. (Texas Monthly’s Skip Hollandsworth wrote about Debrow.) While touring several Texas Youth Commission facilities for a Texas Monthly story about juvenile justice I wrote in 1996, I happened to meet a number of juvenile killers. They all came from low-income backgrounds and were, with few exceptions, children of color.

Yet for the witnesses of the Murchison shooting, their longing for justice has little to do with the length of John’s sentence—and, indeed, many would agree that more juvenile offenders should be treated as John was, rather than the other way around. As University of Texas professor Marilyn Armour, the founder of the Institute of Restorative Justice and Restorative Dialogue, told me, “There are some people who believe that the amount of time served, the severity of the punishment, will bring some measure of closure or satisfaction. According to the research I’ve done, that’s not what happens at all.”

Armour is among the criminal justice reformers who have pressed for opportunities in which all stakeholders in a tragic event can come together and articulate their discontents and needs in the interest of restorative justice. Such occasions have famously occurred in resolving interethnic calamities in South Africa and Rwanda and throughout the Israeli-Palestinian conflicts. On a smaller scale, restorative dialogues have been used in disputes between local police and their respective communities, including in Austin.

In any such scenario, however, the process can succeed only if both sides participate. “Getting answers is what brings resolution,” Armour said. “And beyond getting information, there’s equally the need to express what role this particular event has played in their lives.”

Today, because of the absence of information, those who watched John shoot their teacher are still left wondering about a fundamental question: Has he ever expressed any remorse?

Some of them have searched for answers themselves. A few years before the fortieth anniversary, Ray was visiting Austin and jogging around Lady Bird Lake when he thought he saw John. He looked him up in the phone book and left John a voice mail: “Hey, I know this is weird, but I would really like to get together and talk.” He never heard back.

One person close to John told me that he has felt great sadness over the years for what he did. John’s older brother, George Scott, described him as “a really fine family person. Gentle. He’s been a great uncle to my kids. He’s a really great brother. I have nothing but good things to say about him in the settings I see him in.”

While George Scott fully acknowledged the magnitude of the tragedy for the victims of that day’s events, he also explained that in his view, his brother has “done remarkably well, given the terrible thing that happened. He’s definitely made the most of the opportunity that he’s gotten.”

But George Scott went on to say that he, like the witnesses to the shooting, has been haunted by the incident. “I’ve never spoken with him about it. I’ve talked about it with my wife quite a bit. ‘Should I do that?’ I’m just a scaredy-cat. I’ve been very hesitant to open the issue, and I probably should have. And I may yet do it. I’ve talked to my therapist about this. I’ve been advised it might help me come to terms with it as well. I’ve had the conversation with other people in the family, but not him. It’s crazy. We’ve thought, What happened? What happened? You know, there’s been that conversation. But we have not done a good job bringing it up directly. I’m not proud of that.”

As Ray explained it, “The tragedy is that Mr. Grayson was killed. The collateral continuing tragedy is this silence around the event.” He added, “I know a couple people who’ve said, ‘We don’t know where this [Texas Monthly] story is going.’ They don’t want it to be a hit piece on the Christian family or something that says, ‘This kid escapes justice.’ I don’t want to hurt John. At the same time, I don’t think the opposite of that is to deny what happened to us. I think we can tell the story, we can own the pain, we can call this what it was, without being in the spirit of hurting the person who did it.”

You ask how I got through? Maybe better to ask how I’m getting through. I will never be “over” seeing Mr. Grayson murdered by a friend and classmate. I will never get over losing Olivia. I have gotten through in the past by ignoring the events, denying their reality and power. . . . I’m getting through now by trying to be more honest, trying to show up, pay attention and stay in the game. . . . I seek to put myself, as much as I’m able, in the proximity of others suffering. . . . As a pastor I try and lead our church to embrace the refugee, disabled, those on the margins, those turned away from other churches. I try and pay attention to my own pain and not expect more from myself than I can give, knowing I will be a fraud if I do. . . . I know these words may make me sound noble or wise, but understand, if I knew another way that was easier, one that I didn’t see ending me up as an utter shipwreck, I’d take it in a heartbeat. In the end, this is the only path I see that makes sense, that has any hope, however long the shot. I get no satisfaction from feeling like I’ve found some secret. I’m incredibly grateful for the sense of being found and rescued, in spite of myself, in spite of what could have been, in spite of all that is.

—Letter from John Ray

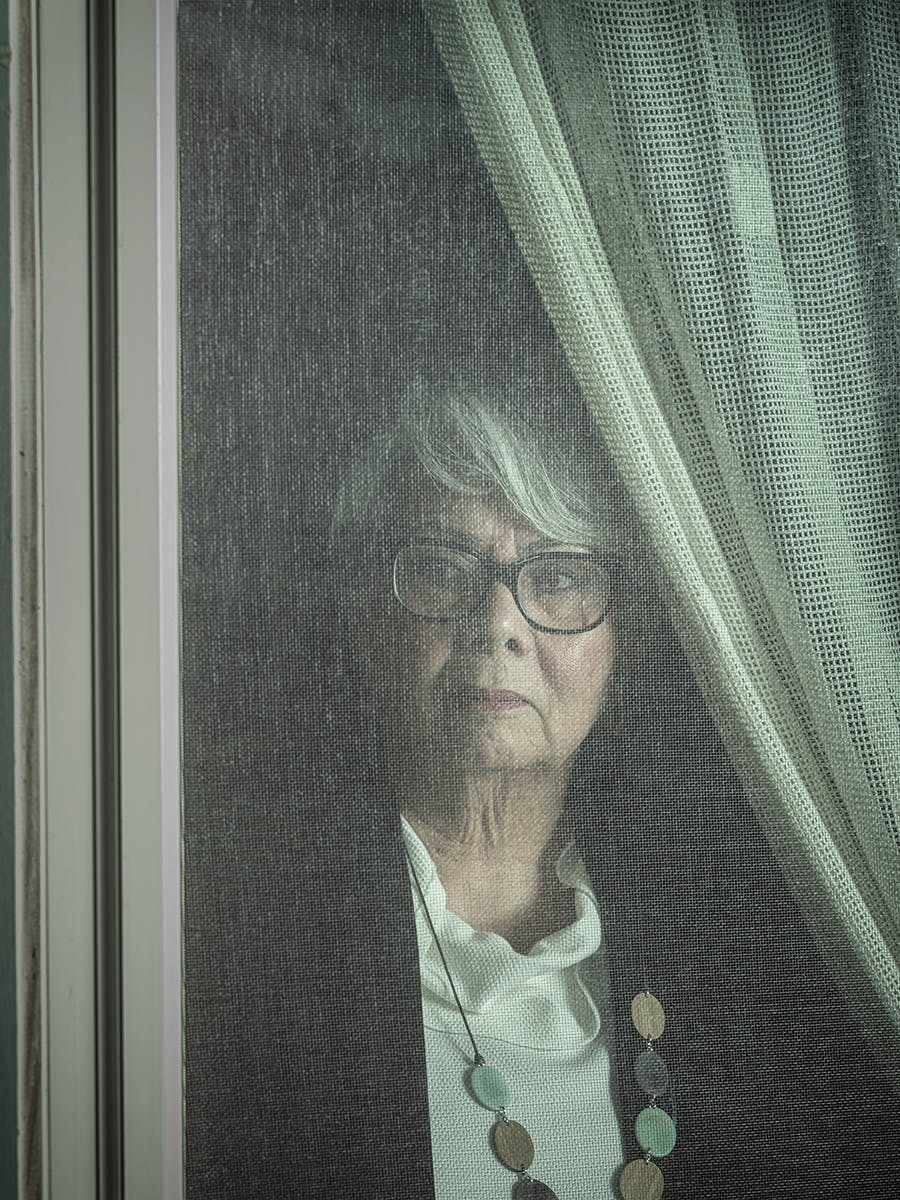

Laura Grayson has been back to the cemetery only once since Rod’s funeral. Their son, Ian, was an eighth grader by then—coincidentally, the same age as Rod’s students when he was killed—and she wanted him to know where his dad’s grave site was, in case he ever wanted to visit. Rod had once told Laura that when he died he would like to be ferried in a boat downriver in the manner of a Viking funeral or maybe sent off into space. Then again, he also said of being buried, “That’s not where I am.”

She knew that. She saw him instead in dreams, and when she lit candles, she remembered how he once laughed at her Catholic rituals and then said, “We’re doing a pact. Whoever dies first has to come back and tell the other if the candles mean anything.” After Rod died, she went to see a psychic, who informed her, “He’s standing behind you. He’s got his hands on your shoulders, and he’s kissing your head. And he wants you to know that every candle you light helps to light the way.”

But where she really saw her husband was in the classroom. Laura had been a teacher before Rod became one, and she continued that work long after he died. Where he had mesmerized Murchison’s gifted and talented, Laura taught mostly those who were socially disadvantaged or at risk. Better to continue applying her passions in this manner, she had decided after his death, than to bask in bitterness.

Easier said than done, of course. Back in the early nineties, Laura happened to meet a woman who had worked as an intake officer at the Gardner Betts juvenile facility, where John had spent two weeks immediately after killing her husband. She recalled that on the same day that John was arrested, two Latino boys were brought in for shoplifting. Those boys were subsequently sentenced to a juvenile institution for their crime. The sense of injustice overwhelmed Laura. “But if I allowed anger to control me, what kind of life would I have made for Ian?” she said. “I remember making that conscious decision.”

She sued the Christians for negligence a year after Rod’s death. Two years later, in 1981, the two sides settled for an undisclosed sum that included a trust fund whose proceeds Ian would receive on his eighteenth and twenty-first birthdays. In 1995, after the first installment of that money arrived, Laura and Ian sought to fund a bench that would be dedicated to Rod, situated on a trail he loved on Lady Bird Lake. She was told by city authorities that no space was available. Laura couldn’t help but wonder if she would have gotten a different answer had her last name been Christian.

Recently, a fellow schoolteacher told Laura that he had traveled to Emporia State University, in Kansas, over spring break to visit the National Teachers Hall of Fame. A new site had been erected, called the Memorial to Fallen Educators, which was designated as a national memorial in 2018. The names engraved on two granite slabs include teachers from Sandy Hook, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Santa Fe—and, yes, Wilbur “Rod” Grayson, from Murchison Junior High.

Now that she’s retired, Laura is hoping to travel to Emporia to see her husband’s name among the others: a roll call of more than 120 heroes, a list that grows every year.

Robert Draper is a contributing editor at Texas Monthly, a contributing writer at National Geographic and the New York Times Magazine, and the author of the upcoming book To Start a War: How the Bush Administration Took America Into Iraq.

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Aftermath.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads

- Crime