This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The Texas power jokes started even before George Bush was elected president. Last fall, after Congress had just approved $100 million for Austin-based Sematech, a veteran Oregon congressman named Les AuCoin approached a Texas colleague, Charles Wilson of Lufkin. “You’ve got the Speaker,” AuCoin said pointedly. “You’ve got Sematech. You’re going to have the next president. What are you going to do next? Move the Oregon national forest to Texas?”

That was before Texas won the supercollider, before the savings and loan rescues, before George Bush named four Texans to his Cabinet. Not even the controversy over John Tower’s nomination could stop the wisecracks. At the Senate confirmation hearing of Secretary of Commerce Robert Mosbacher, John McCain of Arizona joked, “Read my lips: No new Texans.”

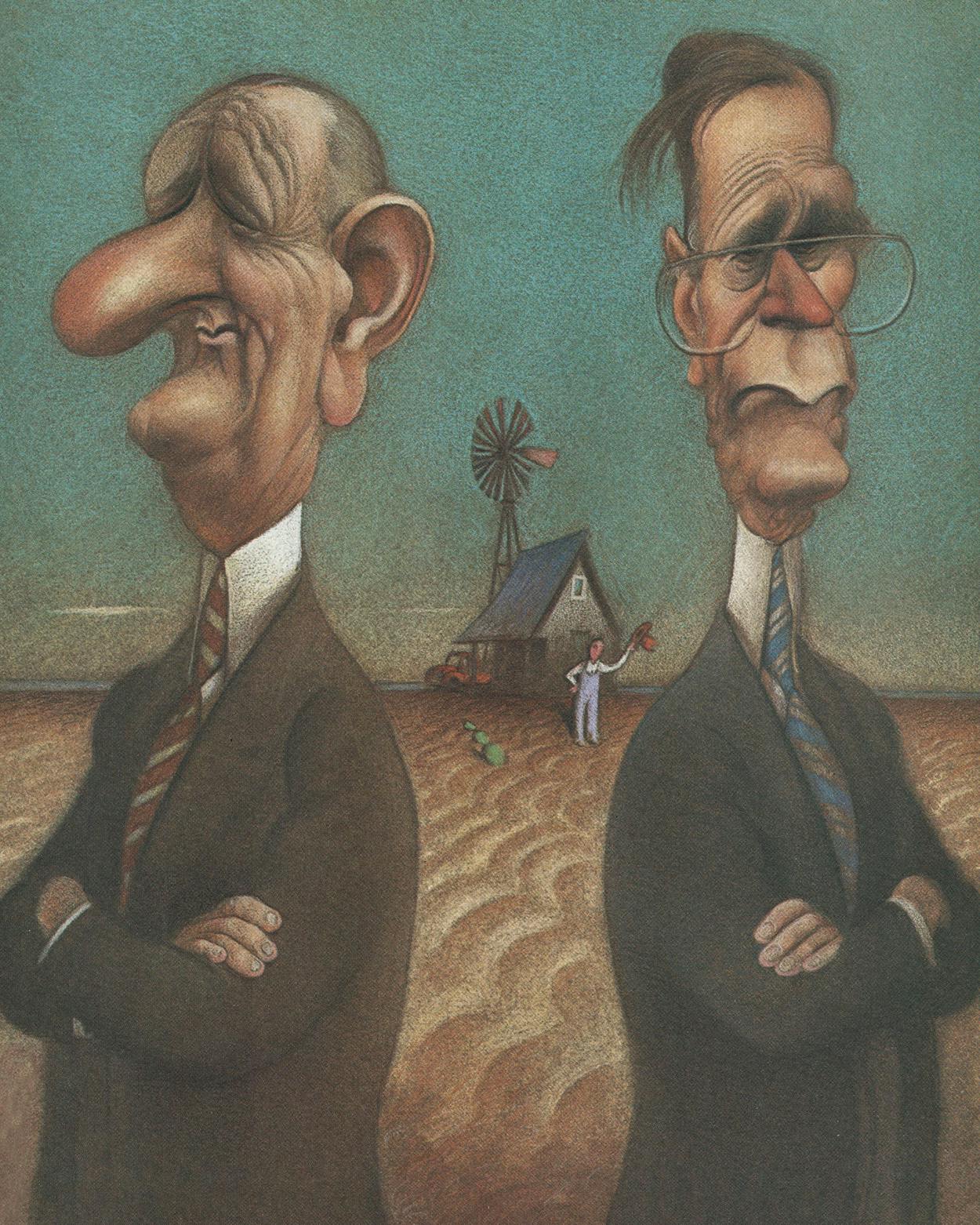

The resurgence of Texas power is almost regarded as a national security issue in Washington. No one is more aghast at the prospect than the media. At the Black Tie and Boots inaugural bash of the Texas State Society, a reporter from People was cornering partygoers to inquire, “How does it feel to be a Texan and what does it mean?” A New York Times headline asked, AS BUSH RIDES IN, IS CAPITAL BIG ENOUGH FOR TEXANS? But it was Life that put into words what everyone was not-so-secretly worried about. Visions of Texans setting national policy for their own parochial benefit spurred the magazine to feature four prominent fellow travelers in its February issue: Secretary of State James Baker, Speaker of the House Jim Wright, Senate Finance Committee chairman Lloyd Bentsen, and Mosbacher. “To the folks back home,” Life warned America, “these men give hope of a return to the glory days of Lyndon B. Johnson, when Texans all but took over D.C. Will this new bunch of power brokers work together to help their ailing home state—say, by hiking the price of oil, bailing out banks and funding Waxahachie’s super collider?”

Please don’t leave out the Oregon national forest. But Washington’s Texas paranoia and the corresponding hopes of Texans back home for a cornucopia of pork betray a misconception about how political power works. Yes, it’s better to have influence than not. But no, George Bush and his Texans will not single-handedly bring back the good times.

The old pork-barrel days are over. Tax cuts and low inflation have reduced the government’s intake; meanwhile, ever-mounting interest payments on the $2 trillion national debt have reduced the funds available for spending. “The concept that there’s a whole lot of stuff waiting for Texans to give to Texas is ridiculous,” says Horace Busby, an LBJ adviser turned Washington wise man. “It’s just not here to do.” Another weakness in the bonanza-for-Texas scenario is that George Bush has never been a pork-barrel politician. He started out in politics at a time when most Texas conservatives became Democrats to preserve the state’s considerable influence in Washington; the rationale for being a Texas Republican was not ideology but clean government. Nothing in his two terms as vice president indicated that he had changed. When a delegation from Houston sought Bush’s help after NASA proposed moving the space-station program to Alabama, he suggested that they make their case to the director of the space agency. Jim Baker was no different. While Baker was Treasury Secretary during Ronald Reagan’s second term, he did not lift a finger to ease the Texas banking crisis. During the tax reform battle, Baker’s Treasury Department testified in favor of eliminating a crucial tax break for oilmen, the master limited partnership.

The point is not that Bush and Baker have turned their backs on Texas; rather, it is that neither is by nature a provincial politician. Nor can Bush afford to be. He is in much the same position as Lyndon Johnson was in 1963: His adversaries (the media in Bush’s case, Kennedy loyalists in Johnson’s) are waiting to pounce on the first display of favoritism. Johnson spent most of his presidency “hiding his Texanness,” Busby says. In five years Johnson had only two Texans in the Cabinet: Attorney General Ramsey Clark, whose politics hardly fit the Texas Democratic mold of that era, and postmaster general Marvin Watson. Not until his last year in office did Johnson allow himself an intense interest in federal projects back home.

A third reason why the Bushmen won’t shower benefits on Texas is that most of them are not in a position to do much. Does it matter that the Secretary of State is a Texan? Even if Jim Baker were inclined to provide for Texas, what could he deliver? At the Pentagon the Secretary’s mission will be to reduce the size of the pie, not to send slices back home. Even if Tower gets confirmed, he will have little direct impact on the two things that matter most to Texas—keeping our military bases open and getting our share of defense contracts. But the former was settled even before Tower’s nomination, and the latter is traditionally decided by the individual armed services, not the Secretary of Defense. Education, headed by Reagan holdover Lauro Cavazos, hands out money according to formulas—no pork there. The Commerce Department, where Mosbacher is in charge, primarily dispenses information, not money.

The items at the top of the Texas wish list are not the kind of political problems that can be fixed by a Cabinet secretary operating quietly inside his own agency or even by a president. They are familiar national issues that will get intense public scrutiny. In order of their importance to the state, they are:

- The savings and loan rescue

- The supercollider

- The space station

- Tax incentives for oilmen

- The Corpus Christi home port

- Sematech

The fate of the Texas agenda will be decided not by the executive branch of government but by the Democrat-controlled legislative branch—where Texas influence is at its highest level since LBJ and Sam Rayburn ran the two houses in the fifties. Henry B. Gonzalez, the new House Banking Committee chairman from San Antonio, is far more crucial to the savings and loan rescue than all the Cabinet Texans combined. Jim Chapman of Sulphur Springs, a new member of the House Appropriations subcommittee that funds the supercollider, will have more say over its destiny than the White House. If naval home-port funding gets into trouble, Speaker Jim Wright will be better placed to save it than the Secretary of Defense. Help for the oil industry, if there is to be any, is more likely to come from Senate Finance Committee chairman Lloyd Bentsen than from George Bush. Legislators, unlike presidents, are forgiven for being parochial; it’s part of the job description.

Bush and his Cabinet won’t be thinking about helping Texas; Lloyd Bentsen, Phil Gramm, and the 27-member House delegation will. Like everyone else in a town of supplicants, they want the Bush administration on their side. The Texas connection will give them access, the most precious political coin in Washington, but it won’t get Texas everything it wants. Neither will leverage at the Capitol. There is too little money and too much opposition—to the supercollider, to higher oil and gas prices, to Texas itself.

But power is not just acquisitive; it is protective as well. It will help the state in ways that no one will ever know, because it will keep bad things from happening. Tower’s confirmation would ensure that Texas defense contractors get a fair hearing; no Pentagon functionary wants to risk getting a call from the Secretary. When agencies have to make budget cuts, they’ll minimize the damage in Texas; no bureaucrat wants to risk getting a call from the White House. Contractors looking for an edge will open plants in Texas.

“The system understands instinctively where the power is,” says Waco congressman Marvin Leath, a Democrat on the House Armed Services Committee. “The little elves in the government know very well that Texas has power, and they know what that means for them.” The biggest thing Texas has going for it is that the perception of power is the essence of power.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Lloyd Bentsen

- George H.W. Bush