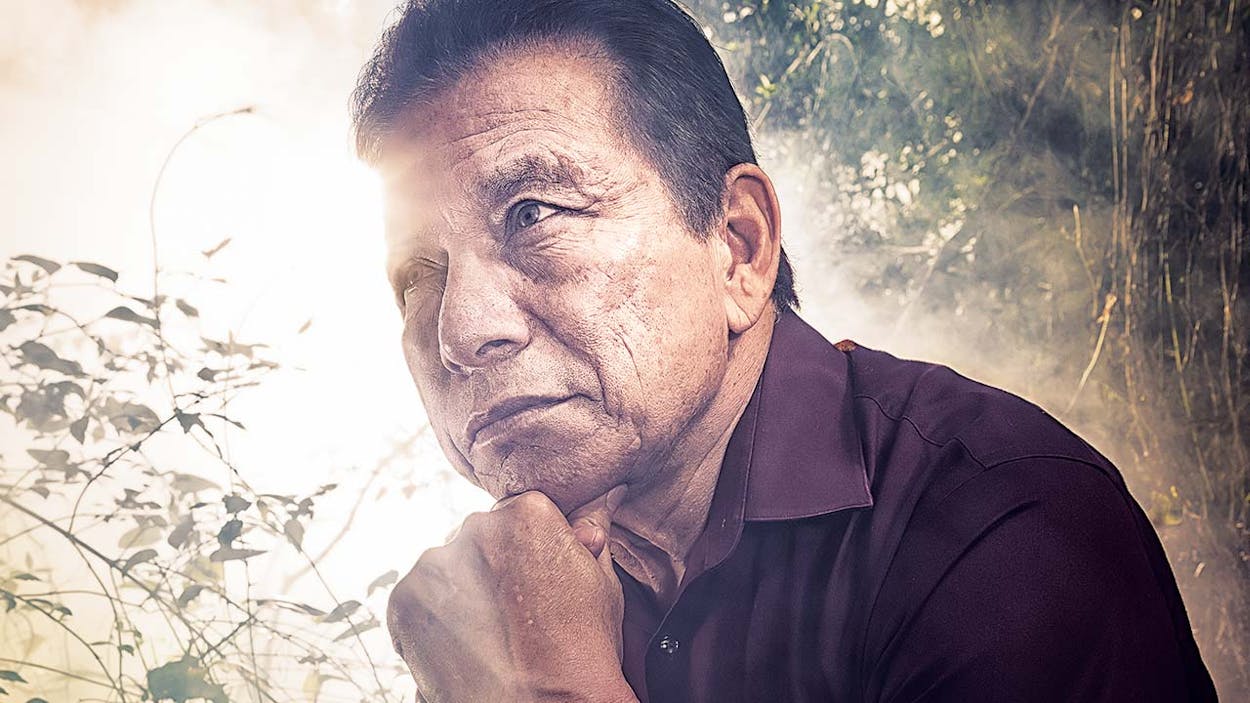

Born in the Big Bend area to a family of Mexican American migrant workers, Hipolito Acosta went on to become one of the most highly decorated officers in the history of U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Acosta’s career found him chasing down human traffickers from Ecuador to England, getting himself smuggled across the border in a sweltering truck full of undocumented immigrants, and working undercover to take down cartel-affiliated heroin kingpins. Now retired and living in East Texas, Acosta has authored a series of memoirs. The third, Deep in the Shadows, is out now from Houston’s Arte Público Press.

John Nova Lomax: You grew up in the small West Texas border town of Redford. Your parents were immigrants, and you spent a lot of time crossing back and forth across the border to visit family. But you and your siblings felt like Americans?

Hipolito Acosta: A lot of us looked forward to growing up and joining the military. There are six brothers in my family; five of us have served in the military. Redford was probably about ninety-nine and a half percent Hispanic, but there was a lot of patriotism, a lot of good feelings about serving the country during World War II. It was never lost on me, the opportunities that our country gave us.

JNL: How big a role do American employers play in the problems we’re seeing with immigration? It seems like we put more of the burden on the immigrants than on the people who hire them.

HA: We’ve gone from maybe 3 million illegal aliens in the United States a couple of decades ago to anywhere from 10 to 13 million now. The reality is they wouldn’t be here if they couldn’t work. And it’s no different under this administration, despite the rhetoric. The administration talks about making it harder for refugees to come into the country. They talk about increasing the number of Border Patrol agents. But they don’t say much about what they’re doing with employers. I think it’s obvious why—we have a president who’s a businessman. If any agent had the guts to do an I-9 audit on Trump’s businesses—of course, nobody has the guts, but if I was an agent, I would do it—they would be surprised by what they would find.

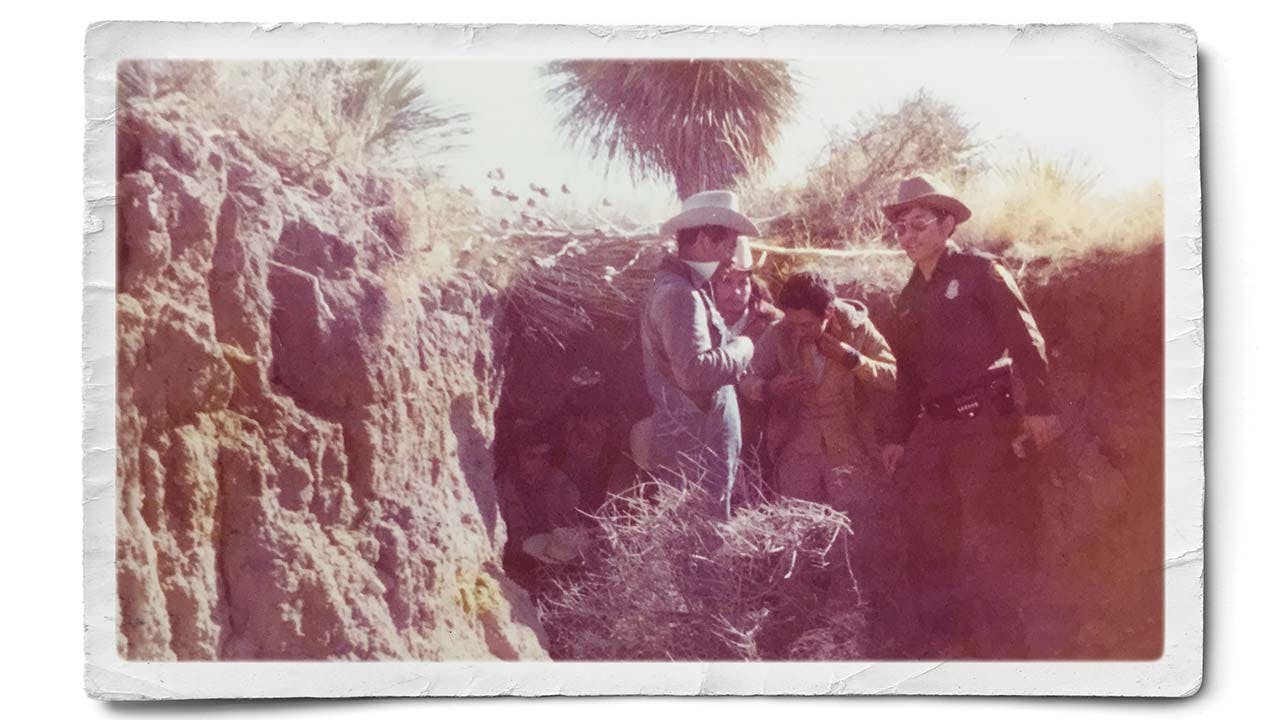

Let me backtrack and say that agents tend to like what the president’s doing. The increased border security is great. The catch-and-release policies are great; the detention is great. But if we don’t start holding employers accountable, the problems will continue. When I was an agent, I walked the mountains of New Mexico for eight hours with a lady who was pregnant. And all she knew was that once she got away from the border and made it into Chicago, she would be home free.

JNL: What do you think of the proposed border wall?

HA: President Trump said he was going to do it, and I think he’s going to be strong-headed about doing it regardless of whether it’s the most effective method or not. There are some areas where a barrier is needed, without a doubt. There are some areas where a barrier or a wall is very effective; it has reduced crime in San Diego, El Paso, Brownsville, and Laredo. But we don’t need a wall from San Diego to Brownsville. It would be deplorable to see my home area, Big Bend National Park, with a thirty-foot wall along the border. People that cross there are probably going to die anyway if they’re walking across that desolate area.

Politicians have a favorite saying: “We are not doing enough to secure the border.” And I would tell them, “We’re not going to secure the border. We’re going to secure Houston. We’re going to secure Dallas.” And for that you need strong employer sanctions and interior enforcement. The Border Patrol does a great job. The barrier does a great job. But if people get through, well, what has happened during the past four decades?

JNL: To what extent do you believe the drug cartels have infiltrated Texas?

HA: The cartels have infiltrated not only Texas—their presence throughout the United States is huge. When I was writing my first book, I learned that one agency had identified a cartel presence in, like, 1,200 U.S. cities. It’s huge. Money laundering is huge. Investment in businesses is huge.

For a long time we thought drug dealers dressed in a certain way, operated a certain way. And we’ve learned over the years that a cartel presence can be somebody who’s an attorney, who’s a doctor, who’s a businessman. In Mexico you see the drug dealers in vehicles and you can spot them. You don’t see that here. They’re smart in the way they operate. And by the way, they don’t all jump the border. That wall won’t stop them.

JNL: I know you loved your job. Was there any part of it you didn’t like?

HA: Once, when I was working undercover, I got smuggled in the back of a U-Haul with a five-year-old kid, and I asked him—foolishly, because I talk too much—“What are you looking forward to doing when you get to Chicago?” And he said, “I can’t hardly wait to start kindergarten.” So, that was difficult, because I’m sitting there in the dark thinking, “You’re never going to make it. I’m going to arrest you before you get there.” Another time, I was talking to a sixteen-year-old kid in a hotel in Juárez, and he says, “When I get to the United States, I want to join the Army because I want to fight for that great country.” He was someone who believed in our nation. But I had to suck it up, because it was my job.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.