This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When outsiders first visit the South Dallas crack neighborhood known as the Zone, they invariably wonder why the city’s wealthiest homes were not built there instead of on the flatter lands north of downtown. The Zone is set in one of the lushest areas of Dallas, a rolling stretch overflowing with catalpa, crape myrtle, and pecan trees. In the last light of day, as children ride their bicycles past the dilapidated frame homes and rusted-out playgrounds, the scene is almost beautiful. On nearly every street, there are one-room churches with names like True Believers Tabernacle or Pure Faith Missionary Baptist Church. During evening services, the sounds of gospel singing slip out of the steel-barred windows and ride the breeze into yards a block or two away.

White people often imagine a crack neighborhood as an American Sarajevo, a combat zone where families move fearfully to the constant drumbeat of semiautomatic weapon fire. In truth, the Zone is peculiarly peaceful, but only because everyone knows to live by the rules of the street. Law-abiding citizens, for example, can tell a visitor the locations of all the crack houses, known as traps, but to avoid being beaten or stabbed, they are smart enough not to say too much else. “They’ll sometimes call to turn in a crack dealer, but they won’t come to testify in court,” says Sergeant Kenneth LeCesne, who has spent five of his eleven years with the Dallas Police Department in its narcotics division. “They know we can’t sit out in front of their houses all day and protect them. Some people from outside the neighborhood talk about organizing an anti-drug parade and painting signs and marching in front of a crack house. Yet after the parade, when the press and the police are gone, the dealers are going to retaliate. A person has to be pretty brave or pretty foolish to go against a dealer. ”

At the end of the eighties, no crack dealer in the Zone was as famous or as feared as Maurice Green, a good-looking ponytailed black man who could have been president of Chase Manhattan Bank, an attorney suggests, if he had just been born in a different environment. Green’s trap was a plain two-bedroom house on Custer Drive guarded by his yard dogs—young men with concealed weapons who stood on the front lawn and warily eyed strangers passing by. On nearby street corners, Green’s lookouts wore the same kind of radio headsets that fast-food employees use to take drive-through hamburger orders. Whenever the lookouts saw an approaching police car, they would broadcast a warning back to the trap, shouting either “Five-O” (after the TV show Hawaii Five-O) or “911.” Instantly, Green’s workers would go on alert, stuffing their crack (cooked rocks of cocaine that make a cracking sound when smoked) into an elevator hidden behind the walls of the trap, where it would disappear into the upper reaches of the attic.

No one in the Zone ever thought Green would be brought down. He was too careful, too crafty. His employees and customers admired him. His enemies didn’t dare turn him in.

But all that changed in mid-1990, when two black Dallas police officers, Randy Harris and Swany Davenport, were assigned to the Zone. As they would later say to the church youth groups and community organizations that gave them awards, they had come to wage war on drug dealers. They busted through crack house doors. They frisked the sunken-eyed pipeheads who made daily trips to the houses. They pushed around the yard dogs and the lookouts, and they scared off the mules who transported the crack. Most of all, they went after Maurice Green, driving up in front of his trap two or three times a night, threatening his workers, confiscating whatever drugs and drug money they could find.

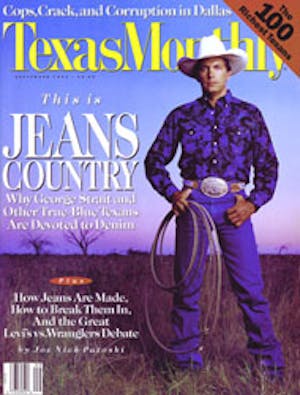

It was not long before other Dallas cops were calling brash linebacker-size Davenport and quiet, intelligent Harris “the black Starsky and Hutch.” A Dallas police sergeant who worked in their substation labeled them heroes.

Within drug circles, however, Harris and Davenport were known by another nickname: Cruiser and Bruiser. Months after the officers began to patrol the Zone, drug dealers were telling every major law enforcement agency in Dallas that the heroes were actually “gangsters with a badge”—vicious blackmailers who demanded up to $2,000 a week per dealer in protection money. Although it seemed the stories couldn’t possibly be true, Dallas police detectives and FBI investigators spent two years interviewing witnesses, secretly tailing Harris and Davenport, and giving some of the Zone’s most notorious dealers, including Green, criminal immunity in exchange for their testimony. Finally, in June 1992, the authorities shocked the city by arresting Harris and Davenport, calling them the most corrupt cops in the history of the Dallas Police Department. The following December, the two officers were convicted of extortion and other drug-related crimes.

Today, Randy Harris and Swany Davenport, who are both 28 years old, live in federal prisons at opposite ends of the country. In telephone conversations, they can barely control the bitterness in their voices. They insist they never broke any law; the supposed extortion plot, they say, was a tale invented by Green and other dealers and swallowed whole by police detectives on a witch-hunt. “We made it our duty to go out and harass drug dealers, to make their lives a living hell,” Harris says. “Now here we are in prison. It’s emotional terrorism.” Some of Harris’ old police colleagues concur, unable to fathom how the allegations of drug dealers could put cops behind bars. Black officers, in particular, are incensed at the racial overtones of a case in which white prosecutors and white police detectives joined forces with dealers just to get two black cops—especially two black cops who were trying to clean up a poor black neighborhood. “Do you think the Dallas police and the FBI would cut a deal with these crack-dealing death merchants to get two white cops?” asks Sergeant Preston Gilstrap, one of the city’s most outspoken black officers. “Never!”

Whatever hot-button issues it raises—race, politics, a police department’s frustrating inability to stop street-smart young drug dealers—the downfall of Randy Harris and Swany Davenport is essentially a morality play about seduction. It is the grim story of two good cops who descended into the Zone to take on Maurice Green and came perilously close to the behavior they had pledged to eradicate. It is difficult to believe that in the brief time that their lives intersected, the man who lived for crime would come to be known as the defender of law and order, while the two who stood for justice would be cast off as villains. But only in a crack neighborhood—where deception is continuous and violence lies just below the surface—could such a battle between good and evil end so calamitously.

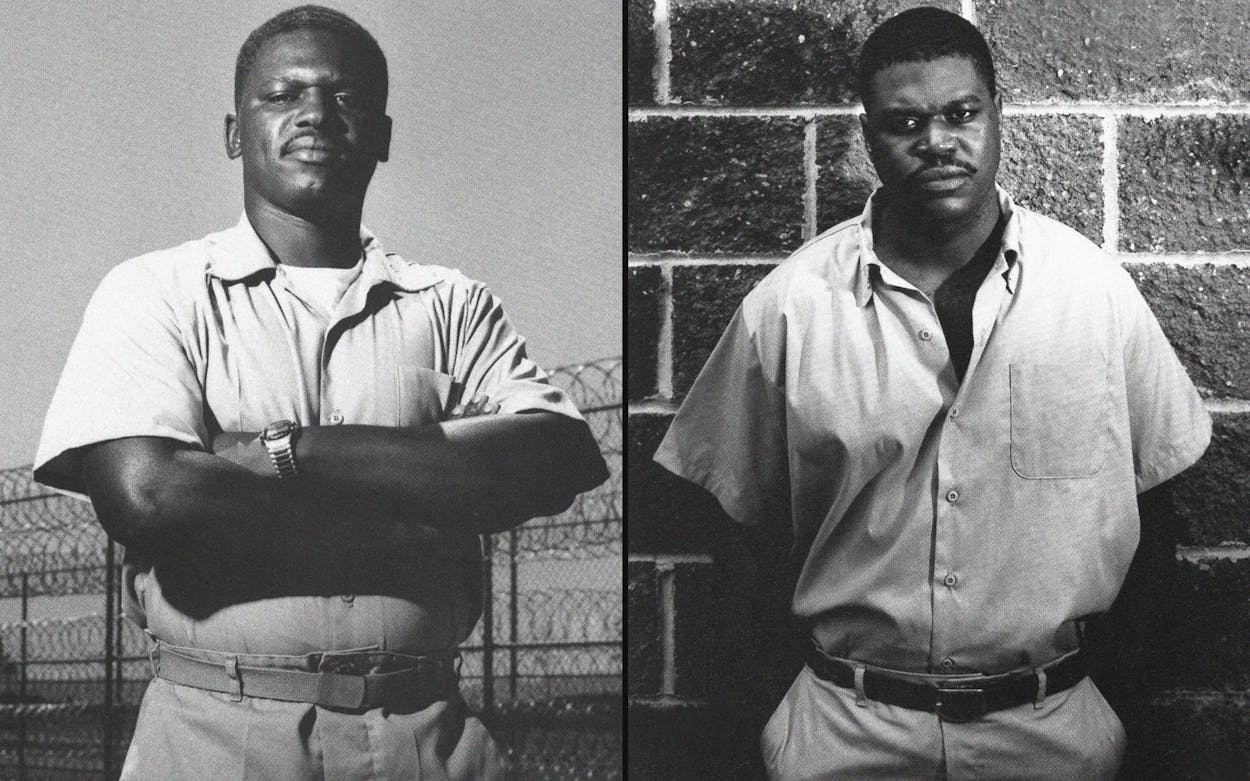

In his gold-tipped python-skin boots and silky shirts, 27-year-old Maurice Green is a villain straight out of Shakespeare—unpredictable and unnerving, yet oddly appealing. Sitting in a stylish Mexican restaurant near downtown Dallas, he smiles flirtatiously at a waitress, and she smiles back. With his soft facial features and his slightly paunchy stomach, he looks almost harmless.

“Only one person has died from my organization,” Green says matter-of-factly, picking at a plate of enchiladas. “He was killed, shot in the head by another organization.” The words echo throughout the room; at the surrounding tables, all conversation comes to a halt. Young people in button-down shirts and blue jeans glance quickly at Green, the only black man in the place. He smiles again, nodding politely.

“Oh, shit,” he says later, his eyebrows arched in amusement. “We’re blowing these white people’s motherf—ing minds.”

Green grew up in the heart of the Zone, raised by his mother after his father abandoned them. He spent time on the streets, hanging out with older teens, learning to think on his feet. Because he didn’t like his mother’s new husband, he often ran away, usually ending up at a juvenile detention center, where other bad kids taught him how to get around the law. When he got out, he would steal cars and joyride for no more than three days, knowing that by then the theft reports would be typed into the police department’s computers.

He could have been a talented athlete: He showed promise as a fullback for the Hillcrest High School football team in North Dallas, where he was bussed every day. But he was a typical kid with an attitude, one who talked back to teachers. Midway through the twelfth grade, tired of wasting valuable time in school, he quit to work as a busboy at a downtown Sheraton, then started parking cars at RepublicBank. When low wages no longer satisfied him, he made his move: In 1988, at age 22, he bought his first rock of crack cocaine for $50 and sold it on a street corner for double that amount. Initially, he planned to work the corners for just a couple of days at a stretch, enough to add $500 to his weekly income. But he was a natural salesman, able to attract business with a smile like a crescent moon across his face. He was also a natural dealer. He was perceptive enough to know when a potential buyer was lying, a critical skill needed to spot undercover cops. If he made a mistake, Green knew which alleys to run down to get away. After a few months of work, he says, “the money started rolling in faster than I had ever seen.”

In 1989, spurred on by his success, Green rented his first trap in the Zone. Although there were nearly a dozen prominent dealers there—such figures as Big Al, Fat Linda, Jamaica Mike, and the Locust Boys—Green quickly made his presence known. In his typically easygoing manner, he lured customers with promises that his cocaine was purer than any other dealer’s. Charm rolled off of him: When an angry rival accused him of shortstopping (sending a worker to stand near another trap in order to direct customers back to his own), Green talked his way out of it. Afterward, just in case he couldn’t talk his way out of it again, he went to a pawnshop and bought three Tech 9mm handguns—the Zone’s gun of choice.

By 1990, Green had so many customers that he had to move his operation to 2515 Custer, a flat one-story house adjoined by two empty lots. It was a perfect location. Because the Zone is flanked on one side by the huge high-fenced Veterans Affairs Medical Center complex and is blocked off from major roads, narcotics officers were already hard-pressed to launch a surprise raid. Yet the Custer trap was even more impenetrable. The rear alley was filled with ruts and potholes—impossible for a squad car to navigate. From the front of the house, Green’s yard dogs could see activity at least a block away. If police officers tried to spy on them from a nearby grove of trees, his workers would jog over and shout, with big grins on their faces, “We see y’all! We see y’all! Y’all ain’t doing nothing slick!”

Although Green rented the trap from an absentee landlord for only $300 a month—because he never purchased anything in his own name, he had a woman friend sign the lease—he spent at least $5,000 remodeling its interior. He put down a new carpet and purchased a stove, a bedroom set, and ceiling fans. He made his workers mow the lawn during the summer and put Christmas lights on the door and window frames during the winter. To Green, the trap was the embodiment of the American Dream. Even today, showing it to a visitor, he speaks about it as reverently as a Chanel-clad realtor describes a North Dallas mansion. “Look how beautiful this place is,” he says, staring at the heavily bricked-in steel-doored, steel-barred fortress. “In the springtime, there’s always a nice honeysuckle smell around this place, man.”

Like other dealers, Green ran his trap as if it were a convenience store. Customers would come to the front door, buy either a $10 baggie (one tenth of a gram of rock cocaine) or a $20 baggie (two tenths of a gram), and return to their homes. Unlike the crack house in Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever, no one hung out at Green’s trap—his yard dogs wouldn’t allow it. No one lived there either—certainly not Green, who owned a $100,000 home in the mostly white South Dallas suburb of Cedar Hill. Yet the trap was never closed for business; it couldn’t be. During evening rush hours, people would line up ten deep outside the front gate. “In that neighborhood,” says one Dallas detective, “the congestion around the traps got so bad that you needed someone to direct traffic.” To accommodate the demand, Green had up to thirty people working for him on any given day. Some were stationed several miles away in one of his safe houses, where the cocaine was brought in and cooked. Others worked at a house where the crack was cut up and bagged. Still others guarded a house with a walk-in safe, where Green kept money and excess cocaine.

Most of the time, the Dallas Vice squad was too busy patrolling the city’s other drug-addled areas to disrupt Green’s operation, but even when they targeted him, he hardly worked up a sweat. Getting hassled every once in a while was the price of doing business. To keep his losses to a minimum, Green would allow no more than $5,000 in cash and $5,000 worth of crack to remain in the trap; his mules carried the rest away to one of his safe houses. To reduce the number of arrests Vice could make, Green would hire a lawyer to come to the trap on weekends to give workers seminars on search-and-seizure laws. The workers were trained to get into another room during a Vice raid, away from the crack, so that no legal “affirmative link” could be made associating them with the drugs. To minimize the effect of the damage Vice would do—from tearing off burglar-proof bars to breaking down doors—Green had his “contractor” (a neighborhood handyman) on standby. Within two hours after a raid, the house would be repaired, and the operation would be up and running.

At its height, according to court testimony, the Custer trap was bringing in $80,000 a week; more than half—$50,000—was pure profit. Green’s two top lieutenants were making $5,000 to $6,000 a week. His top mule was earning $1,500. His salesmen made $1,000. Lookouts and yard dogs made $300 to $500. Green paid himself between $10,000 and $15,000.

To middle- and upper-class whites, Maurice Green was certainly a symbol of everything real and terrifying about urban America. To this day he has never been to prison. He regularly mocked the “blue suits,” his derisive nickname for uniformed patrol officers, laughing and waving at them as they drove by his trap or staked him out. Although he never smoked crack himself—he was far too ambitious for that—he was utterly indifferent to the fact that his dealing created crack babies and sallow-skinned addicts. Indignantly, he would insist that he didn’t force people to smoke anything: They were making their own choices. He wasn’t bringing the cocaine into the country, he liked to say. If the government was going to allow it to slip in, he might as well sell it.

Such brazen disregard for the law and the lives of people might turn off residents of another community, but in the Zone, where there are few jobs and little hope, an empowering take-charge attitude goes a long way—even if you’re as dangerous as Maurice Green. In the absence of real opportunity, Green’s manipulation of the underground economy had a tantalizing appeal. Every day, kids from the Zone would adoringly chase after Green’s Lincoln Continental because they knew he would pass out $5 or $10 bills from his car window. People would talk about the way he was investing his drug money in useful legitimate ventures such as a neighborhood pool hall or a used-car dealership. He was also an extremely polite neighbor. During a rare gun battle one evening between his yard dogs and those of a rival dealer, a stray bullet went through an elderly woman’s home across the street and lodged in the bathroom wall above her toilet. Even though he knew the woman regularly called the police to complain about his trap, he sent his contractor to fix the damage.

As one law enforcement agent would later say of Green: “He was a very likable guy. You just had to keep reminding yourself that he’d cut your heart out in a minute.”

By all accounts, the integrity of officers Randy Harris and Swany Davenport was stronger than a bank vault. Born and raised in Louisiana, a cum laude graduate of Grambling State University with a degree in criminal justice, Harris planned to attend law school until he heard an inspiring talk by a Grambling graduate who had gone to work as a Dallas cop. The cop said the racially imbalanced Dallas police force needed more minority officers to change the system—to help end racist behavior by white officers toward black citizens and to encourage more minority hiring and promotion by department officials. The religiously devout Harris, a student of the teachings of Martin Luther King, Jr., felt a calling to the city, especially to its underprivileged neighborhoods. “If you’re an eager, determined officer,” he says, “you have the opportunity to save lives.”

Swany Davenport, born a month after Harris, grew up in a modest black neighborhood three miles from the Zone. Like Maurice Green, Davenport was a small child when his father moved away. But instead of hitting the streets, the boy stayed by the side of his mother, Carrie, who worked one full-time job and two part-time jobs to support the family. By age twelve, Davenport was also working part-time, first as a delivery boy, then at a nursing home, then at a school district warehouse. He was a congenial, fun-loving kid who “never did go up Fool’s Hill,” Carrie Davenport says. “If he was at a friend’s house or at a party and wanted to stay out late, he’d call me and ask if it was all right. ”

Though Davenport and Green never knew one another growing up, each certainly knew the area of town where the other was raised. Davenport angrily remembers Sunday services at Jordan Missionary Baptist Church at the edge of the Zone, where he worshiped as a boy. To keep the kids and drug addicts from breaking into the parishioners’ cars, church deacons had to stand guard in the parking lot. Davenport says that during services, he could hear the contemptuous Zone boys outside, making noise and causing trouble. “I thought if I ever got a chance, I would deter some of that crime,” he says, his voice still firm and resolute.

After graduating from Paul Quinn College in Waco with a degree in computer science, Davenport entered the Dallas Police Academy, where he met Harris, who was in the same class. They graduated in 1989 with high marks and were sent to work in South Dallas, where they soon paired up on an evening shift that had them patrolling the Zone. The five-eleven Harris and the six-three Davenport were exactly the kind of officers that the Dallas Police Department needed: intelligent, articulate, and nonwhite (only 536 of the department’s 2,259 officers are black).

Yet they were far from alike. Randy Harris was married to his junior high school sweetheart and worked on his off-days as co-youth director at South Dallas’ New Jerusalem Institutional Baptist Church. There, he gave talks on sexual promiscuity, obedience to one’s family, and drug and alcohol abuse, and he started a football league. “He always wanted to talk to kids about the kinds of problems they were facing,” says a minister who is one of his lifelong friends. “He was like a parent for some of those boys. ”

Although Swany Davenport also was married and attended church, his personality was clearly more aggressive. One supervisor who worked with Davenport remembers him as “a thrill-seeker,” and it was no secret to his fellow officers that he had several affairs during his marriage; among his girlfriends were a banker, a nurse, and a hospital clerk. On one occasion, Davenport received an official reprimand for entering a nightclub while on duty. He told his bosses that he had not gone in to meet a woman but had just dropped by to say a quick hello to one of his friends who was getting married.

Of course, such incidents do not suggest that Davenport was harboring a criminal side. It was, in fact, his very love of the chase that made him a good, upstanding cop. “Apparently, it didn’t matter what he chased—girls or dope dealers,” says one of his former supervisors. “He caught his prey. ”

During the time they spent on the force, Davenport received twelve commendations from the department and Harris received nineteen—impressive numbers for young officers. Together they received a 1990 Outstanding Law Enforcement Award from the Greater Dallas Community Relations Commission. A local minister who rode one evening with the officers recalls how the two men were dispatched to a home where a sixteen-year-old boy had locked himself into a room and was threatening to commit suicide. After gently talking to the boy, the minister recalls, Harris and Davenport persuaded him to drop the knife he was holding and open the door.

Ultimately, however, Harris and Davenport made their mark chasing drug dealers. “We saw drugs as the common denominator in every problem that existed in the area,” Harris says. Davenport, who lived just eight blocks from the Zone, would point out to Harris teenage boys making their first moves into a crack organization by dealing rock cocaine on street corners, as well as teenage girls turning themselves into “strawberries,” trading their bodies for drugs. Such activity enraged Davenport, the father of a four-year-old daughter. “What if my little girl got hooked up with these dealers?” he would ask his friends. “What if she got caught in a drive-by shooting?”

Between the usual dispatch calls that they were required to handle, Harris and Davenport began driving past traps. They tried to make arrests, at least ticketing those cars that were illegally parked. They wrote tickets just to bother the customers and workers—including one to a guy who failed to identify himself—and sometimes frisked everyone they found outside the trap.

But as the months wore on, the officers realized they weren’t getting close to the big-time dealers or any of their associates. “It made you feel like no matter how hard you tried, it wasn’t going to work,” says Harris in a revealing admission. “No matter what kind of answer you had, they had a bigger answer. ”

Part of the problem, to be sure, was the wily behavior of the dealers, who had had run-ins with the police for so long that they knew how to cover themselves. At Maurice Green’s trap, for instance, salesmen would make someone who they thought was a narc smoke a rock of cocaine in front of them. If he hesitated, they knew he was a cop, for a dope fiend would never think twice about using for free. But much of the problem the officers encountered was the law itself. To get a court-ordered search warrant to bust a trap, an undercover cop must make a drug buy there to show probable cause that it is the center of a drug operation. Any conduct that does not follow that routine precisely, however well-meaning, is illegal—a violation of the suspect’s Fourth Amendment rights. In other words, the constitutional protections given to good citizens to prevent abuses of power are the very protections used by drug dealers to stymie the police.

Driven by their idealism—or perhaps their exasperation—Harris and Davenport decided to get bolder. If they had to bend a few laws to beat the dealers, so be it. Although they would tell their supervisors that they were engaging in legal “hot pursuits” of workers and customers who were trying to escape, the truth was that Harris and Davenport were busting into traps without probable cause and confiscating all the drugs, money, and guns they could find. They didn’t concentrate on making arrests, because they knew they couldn’t prove the strong affirmative links that workers at the traps had been trained to avoid.

Eventually, word of Harris and Davenport’s tactics began to spread. Dallas police sergeant Preston Gilstrap, who went to church in the Zone a block from Green’s trap, heard from other parishioners about two new cops “kicking the drug dealers’ butts.” Another sergeant said the amount of guns, ammunition, and crack seized by the officers and turned in at the department’s property room was “astronomical.”

The Zone’s dealers, bumping into each other at nightclubs like Fat Sally’s or the Savoy, also swapped stories about the two blue suits they knew only as Cruiser and Bruiser. (The dealers aren’t sure who coined the names, but they say the officers put black tape over their name tags to hide their true identities.) “They’re tearing us up,” they would say over and over. Some dealers described how they were being driven into bankruptcy because their customers, scared of the rogue cops, stayed away from the traps. At one point, at least seven dealers, including Maurice Green, came together at an underworld-style summit meeting to discuss paying a Fort Worth hit man $15,000 to kill Cruiser and Bruiser. The idea was quickly dismissed: The whole police force, they agreed, would sweep through the Zone, arresting everyone on trumped-up charges just to avenge the officers’ murders.

Still, something had to be done. According to the ethics of the drug world, no blue suit should be able to take a dealer’s lifeblood—his drugs and money—without at least having a search warrant or making an arrest. Green was especially upset: It appeared that Cruiser and Bruiser had targeted his operation more than the others. His workers were telling him the officers would hit the trap at least once a night, doing whatever it took to get inside. The first time they came, the workers said, Cruiser and Bruiser drew their guns, forced them to the ground, pried off a side window, and crawled through. Green told his workers to install more burglar-proof bars, but the officers, wielding a crowbar, still got in. A furious Green had his workers add even more bars, brick up the windows, and reinforce the steel doors with dead bolts. Undaunted, Cruiser and Bruiser returned one evening, pulled back some aluminum siding to get into the garage, climbed into the attic, walked across roof beams, and dropped through the kitchen ceiling with their guns drawn. Over a period of four months, the two officers confiscated at least 300 baggies of crack and 38 handguns from Green’s trap.

There was no question that Harris and Davenport were operating in a gray area of the law—they never even attempted to get a search warrant—yet no supervisors were complaining. Why should they? Few officers ever ventured into the Zone after dark; Vice was known to conduct its raids only in the daytime. For better or worse, the Zone belonged to Harris and Davenport and their cop-show antics. First came Davenport, the thrill-seeker, bolting out of the car, pulling his gun on the yard dogs, and banging through the crack house door. Then came Harris, silent as ever, concentrating, scoping out the hiding places where the dealers stashed their crack. As Green himself would later admit, Harris was “like a hound dog,” always able to sniff out the drugs.

The seduction began, it is said, at one in the morning on October 20, 1990, when Randy Harris, Swany Davenport, and Maurice Green came face to face for the first time. Green had dropped by his trap for a brief visit when a squad car with its lights off suddenly roared around the corner. “All you could hear from everyone around the yard was, ‘Uh-oh, here come Cruiser and Bruiser,’ ” Green recalls. The officers jumped out and ordered everyone to hit the ground. Green was in his nice going-out clothes—he was planning to drop by a nightclub—and he wasn’t about to risk wrinkling his shirt. “I ain’t getting on the ground, not for no blue suit,” Green yelled. “You blue suits can’t come into my motherf—ing house!”

Davenport swung around. “You Maurice?” he asked.

“That’s my name. I’m just over here talking to some homeboys.”

“Look, man, we know what’s going on,” Davenport said. “We know what y’all are doing out here.”

Davenport then pulled Green over to the squad car. According to Green, Davenport leaned forward and quietly said, “What is it worth for us to leave you alone?”

“Man,” Green replied, “I don’t know what you are talking about.”

What was Davenport talking about? Depending on who you believe, either Harris and Davenport had set out on a daring scheme to lure Green to the side of goodness—or, incredibly, they themselves had given in to evil.

Harris and Davenport say they wanted to talk to Green because they hoped to turn him into a confidential informant. They were going to keep harassing him and raiding his trap, even if it wasn’t strictly legal, until he agreed to give them valuable details about drug activity in the neighborhood. Their ultimate goal, they say, was to capture someone much more important: the drug kingpin who was providing the crack to the dealers. “There’s somebody bigger than Maurice,” Harris says, “someone who’s probably white and living in a suburban area.” In a way, the plan made sense. If the officers merely shut down Green’s operation, a new dealer would immediately show up to take his place. But if they put the screws to Green and forced him to lead them to the source of the Zone’s drugs, they just might be able to cripple the entire drug trade.

If Green’s version of the story is to be believed, when Davenport took him aside that night, he demanded a bribe—protection money in return for the officers’ leaving his trap alone. According to Green, Davenport said, “If you want us to stop busting up your house, you gotta pay your taxes.”

It is not difficult to understand how officers who patrol crack neighborhoods might be tempted to skim some of the money they confiscate. As the old saying goes, “The policeman never rubs off on the street; the street always rubs off on the policeman.” Randy Harris and Swany Davenport were each earning $27,000 a year—about half of what Maurice Green’s trap made in a week. Even for someone as serene and spiritual as Harris—living in an apartment, unable to get a home loan, working a lousy part-time job as a bank security guard to pay off his college loans—there had to be something enticing about all the cash they found in those shabby traps. At the time of the busts, Harris’ wife was pregnant with their second child, while Davenport not only had to support his wife and child but also allegedly was paying part of a girlfriend’s rent. What difference would it make if the only two cops in town willing to risk their lives to clean up the Zone happened to slip a little of Maurice Green’s booty into their pockets? Who would ever know? They could still turn most of what they uncovered over to the police property room.

Regardless of who was deluding whom, a certain relationship had begun to develop among the three men—particularly between Davenport and Green. Though not as intelligent as Harris, Davenport was clearly the team leader, the one who always did the talking when they pulled up to a trap. Far more than his partner, Davenport probably had his reasons for wanting to outwit the wealthy young dealers. Perhaps he needed to prove himself—to prove that he, the kid from the good neighborhood, could triumph over them, the kids from the Zone, the former juvenile delinquents who used to shout outside his church. Green believes Davenport had an inferiority complex because he had never been tough enough to hang with the homeboys. “He was the kind of sissy who got his ass whupped in school,” Green says. “He became a police officer just to get his revenge.”

Indeed, there are hints that Davenport liked mixing it up with the dealers. Green says that Davenport, driving his own brown Cougar, would sometimes drop by the Custer trap during his off-hours to shoot the breeze. Once, Green says, Davenport brought along a portable television so that they could sit in the front seat of his car and watch news reports of the Persian Gulf War. Perhaps Davenport was acting friendly in order to persuade Green to become a snitch. Or perhaps it was Green acting friendly in order to charm Davenport and get him off his back.

Another time, in an extraordinary scene, Davenport called Green, asking to meet him at a Showbiz Pizza. Green, who is divorced, arrived with his three young children; Davenport came with his wife and daughter. After the kids went off to play video games together and Davenport’s wife—who had recently quit her job at a beauty parlor to enter the Dallas Police Academy—moved to another table, the two men got down to business. According to Davenport, the conversation touched on his desire to turn Green into a snitch. In Green’s version of events, Davenport arranged the meeting to negotiate a deal to get protection money.

As Green remembers it, Davenport talked about a white bank president in Dallas who was about to be busted for drug possession until top police officials pulled everyone off the case. “They want us to bust all of y’all black dealers,” Davenport allegedly said, “but not the white people. That’s the reason we’re here—to help y’all. We just want a piece of the pie.” Green claims that Davenport promised, in exchange for monthly payments, to leave his trap alone and inform him of any potential raids.

Green says he refused to pay—and sure enough, a few nights later, Harris and Davenport came to his trap, suddenly handcuffed his two top lieutenants, stuffed them in a squad car, and drove them around South Dallas. Soon after, Green says, Davenport called him on a mobile phone and demanded ransom money. Finally, following two hours of negotiations, Green agreed to pay $5,000 for his lieutenants’ release. He was told to drive to a nearby Church’s Fried Chicken, where a young woman slipped up to the front window of his Lincoln Continental, took the money, and disappeared.

After that, Green says, he finally gave up. He made a deal to pay the officers $2,000 a week—the same amount, he later claimed, that other neighborhood dealers were paying them.

Stories first began to trickle into the Dallas Police Department in November 1990. A detective heard from a Dallas lawyer representing an anonymous client that two black officers known as Cruiser and Bruiser were shaking down crack dealers at night in a certain South Dallas neighborhood. The detective researched police files until he came up with the names Randy Harris and Swany Davenport—the only black partners who worked that area of the city in the evening. After looking at their arrest reports and noting how aggressively they were hitting drug houses, he dismissed the complaint as the grumblings of a disgruntled dealer.

Then, in January 1991, narcotics officers executed a search warrant on a Zone trap run by Don Hardge, a longtime dealer who could barely read or write but was known to be good with a gun. Soon after the arrest, a prominent Dallas defense attorney called police officials and said that in exchange for criminal charges’ being dropped against Hardge and his workers, Hardge was willing to tell a remarkable story about crooked cops called Cruiser and Bruiser.

Not long after news of the call reached the desk of then Dallas police chief Bill Rathburn, two of the department’s veteran bloodhound detectives—Ronnie Hale and Barry Whisenhunt of the Special Investigations Unit—were put on the case. They asked Hardge to look at photos of police officers, and almost immediately he pointed to a shot of Randy Harris. “There’s Cruiser,” he said. Then he pointed to Swany Davenport. “There’s Bruiser. ”

Hale and Whisenhunt were detectives of the old school, so they didn’t put much stock in anything a dealer told them—especially one who was getting a drug charge dropped. But then Hale and Whisenhunt checked out Harris and Davenport’s record: Their arrests had gone down significantly, from a high of 22 in September to a total of 7 in November and December. The amount of property they had confiscated from traps had been truly significant, but toward the end of November, it too had begun to decline. Why?

The detectives suspected that Harris and Davenport were extorting money, but they needed proof. They considered putting video cameras into Don Hardge’s trap, but that idea was nixed: Cruiser and Bruiser might see them. Maybe they should place an undercover officer in Hardge’s trap and wait for the officers to bust in. Or maybe undercover officers should open their own trap in the Zone to lure Harris and Davenport. The Dallas police running its own trap? If such efforts were ever made public, the department would be the laughingstock of the city.

Finally, the detectives decided to bring in an undercover officer from the Department of Public Safety (so there would be no chance that Harris and Davenport would recognize him), dress him up like a drug dealer, and station him in front of a convenience store with a cookie tin containing $1,800. At the agreed-upon hour, the police dispatcher sent an order to Harris and Davenport to check out a complaint about the alleged dealer. The two officers drove up, searched the man, questioned him, and found the money. The moment was at hand—yet they took nothing and told the man to get out of town. They had an easy opportunity to make a quick profit off a dealer, and they passed it up.

Plainclothes officers who had been tailing Harris and Davenport for five consecutive evenings also reported no shakedowns, no payoffs, not even an illegal search and seizure. They did say, however, that the two men had been less than diligent in taking general emergency calls from the dispatcher. It is common knowledge that every police officer, after being called to a scene of a potential crime or accident, occasionally takes a break before reporting back that he’s available for another assignment. But Harris and Davenport remained “marked out” on several calls that they had already finished. While still marked out on a missing-child call, they drove to an out-of-the-way apartment house, presumably so Davenport could see one of his girlfriends. Another time, a fellow officer radioed for backup, yet Harris and Davenport never took the time to respond.

In a final attempt to make a case against the officers, Hale and Whisenhunt hauled them in for an interrogation. Confronted with the allegations, Harris looked stunned; he said he was an honest cop and would always be an honest cop. According to Hale’s notes, Harris spoke in a polite, soft voice. He was the earnest officer, the family man, the young church leader—the kind of guy who could have gone far in the department. By contrast, Hale says, Davenport saw himself as “a righteous Clint Eastwood figure.” The two officers admitted they had kicked in the doors of a few crack houses, but only in an effort to clean up the Zone. “Somebody’s got to do something,” Davenport said, “and we’re out there trying.”

Harris and Davenport survived the interrogation, but because of their poor response time on calls, they were put on paid suspension. Given their negligence, department officials alleged that they were too great a liability to be on the streets. As word of the suspension circulated, some officers began to doubt Harris and Davenport’s innocence. (Around this time—perhaps coincidentally—Davenport’s wife left him.) Others, including Harris and Davenport’s supervising sergeant, argued that the two were being railroaded on questionable administrative charges.

For the next two months, the case remained at a standstill. Then, on April 11, 1991, narcotics officers from the Dallas Sheriff’s Department stormed an alleged safe house located in a South Dallas apartment complex. There they found a safe containing half a kilo of cocaine. They also found, sitting on the couch, Maurice Green. The legendary dealer from the Zone had been caught redhanded. “We finally got your ass!” an undercover cop yelled.

In fact, they hadn’t. A few days later, a shocked Ronnie Hale received a phone call from the same Dallas attorney who had contacted him about Hardge. The attorney was now representing Green; if the DA’s office was willing to drop all charges against him, Green would provide even more information on Cruiser and Bruiser. Hale met with the DA’s top assistants, who then asked the sheriff’s department to let its prize catch go. “How long is this going to go on?” one sheriff’s official complained to Hale. “Are you going to cut loose every drug dealer who says they have a Cruiser and Bruiser story?”

The whole thing seemed fishy: different dealers using the same attorney to tell the same story? For days, Hale and Whisenhunt listened to Green and his associates. Green picked out Harris and Davenport from a photo lineup. When detectives showed Green a lineup of women that included Davenport’s present and past girlfriends, he pointed to Angela Elzy—Davenport’s girlfriend from the V. A. Medical Center right next to the Zone. She was the one, Green said, who collected the ransom money at Church’s Fried Chicken.

The detectives were now convinced that the officers were guilty. “Here was this sorry, no-good, low-life dope dealer,” Whisenhunt says, “and in this specific instance, he was the victim.”

But in the summer of 1991, prosecutors from the DA’s office suddenly pulled back: Because they believed there wasn’t enough evidence to convict Cruiser and Bruiser, they were dropping the case. A trial would come down to the word of sleazy drug dealers versus that of two respectable-looking cops. In a city where minority groups regularly protested allegedly racist prosecutions, the case would be political dynamite.

Suddenly, police officials had nothing to show for months of work. Because of immunity agreements, all the drug dealers were back on the streets, working their traps, and the supposedly crooked cops would soon be back on the beat. Furious over the outcome of the investigation, police chief Bill Rathburn decided to go ahead and fire the officers anyway, citing administrative violations. And to show that they were seriously waging a war on drugs, he instructed his deputies to begin the tortuously slow civil court process required to get a permanent condemnation order on Maurice Green’s Custer trap.

Of course, Green got the last laugh. The day after the police made their raid, padlocked his doors, and gave interviews to the local news media, he rented a new trap two doors away and opened again for business.

Finally, it seemed, the Cruiser and Bruiser controversy was put to rest—yet there was one more revelation to come. In June 1992, almost a year after the Dallas DA’s office had dropped the case, a federal grand jury indicted Harris and Davenport on federal charges of extortion, conspiracy, and cocaine distribution. Rathburn, apparently unwilling to give up the fight, had swallowed his pride and secretly asked for help from the FBI, the department’s archrival.

The new investigation had been led by John McSwain, a young white agent from the Bureau’s white-collar-crime division. It was hard to believe that McSwain, a former accountant, could get suspicious black drug dealers to provide more concrete information about Cruiser and Bruiser. But after staking out Maurice Green’s house for days in order to serve him a subpoena, he proved himself to be extremely persuasive. According to Green, McSwain brusquely told him that if he didn’t tell all he knew in court, the FBI would run him in for tax evasion and money laundering. (McSwain denies making such a threat.) Around the same time, a top lieutenant of Green’s decided to testify after a felony gun possession charge was mysteriously dropped. Most important, when McSwain heard that Swany Davenport had broken up with his old girlfriend Angela Elzy, he appeared one evening at her door with pictures of other women Davenport had been dating during their supposedly monogamous relationship. It was the old jilted-lover trick. Devastated by the revelations, Elzy confessed that she had been the “bag lady” who picked up the dealers’ protection money for Harris and Davenport.

In the weeks that followed, the two officers amassed ammunition of their own: They hired Peter Lesser and Roger Joyner, brazen defense attorneys infamous for their attacks against the Dallas Police Department. Mounting an intense campaign on behalf of his clients, Lesser bluntly said that other, dirtier cops higher up in the department might be receiving bribes from dealers to protect the Zone—which is why Harris and Davenport had to be brought down. He produced a sworn statement from a female acquaintance of Green’s who said she had overheard him bragging about “setting up” two cops. In another statement, a woman who had worked at Don Hardge’s trap said Green had asked her to tell the police that Davenport had once made her perform oral sex on him.

At the trial, Lesser and Joyner denounced the government’s tactics as coercion. What drug dealer, they asked, would not testify against a police officer if it would keep him out of jail? (Angela Elzy, in fact, later recanted her confession, saying that McSwain caught her at a weak time, that she had said what she said only to get back at the two-timing Davenport, a man she truly cared for.) Lesser told the jury that Green and Davenport talked so often on the phone because Green had turned into a snitch to save his own trap. Green later invented the “protection money” story, he said, in order to get the officers arrested and out of the neighborhood: If the other dealers had discovered he had informed on them, he would have been murdered. In the Zone, Lesser said, “snitches end up dead.”

Outside the courtroom, opinions were sharply divided over the likelihood of a conviction. Indeed, the case looked flimsy—a group of dealers, with long criminal records, leaving their drug operations for the day to drive downtown to the federal courthouse to tell a jury that two cops were doing them wrong.

What changed some people’s minds was Maurice Green, the prosecution’s star witness. He arrived in a designer suit, his hair slicked back into a small red-tinged ponytail, and from the moment he began to testify, he righteously proclaimed that he had never ratted on anyone. He regaled the courtroom with tales of the drug trade and management anecdotes worthy of a Harvard Business School course. On cross-examination, defense attorneys bombarded him with trick questions in an attempt to shake his story, but Green kept his cool. When one attorney asked indignantly, “It is hard to keep all these lies straight in your head, isn’t it?” Green replied, in a clear voice, with his head held high, “They are not lies.” From the defendants’ table, sitting silently in their dark blue suits, Harris and Davenport shook their heads in disgust. But the jurors paid rapt attention to Green, perhaps fascinated with his insidious, swaggering personality in the same way that the young officers once had been.

The jury was also swayed by the evidence, most of which seemed to bolster Green’s story. There was, for example, the infamous night when Green’s lieutenants were allegedly kidnapped. Harris and Davenport had been “marked out” on an emergency call—they were supposed to be investigating a domestic disturbance at an apartment complex. Yet the residents of the complex who made the call said no officers arrived. Mobile phone records for the same night showed a flurry of phone calls between the officers and Green and also between the officers and Elzy, their would-be bag lady.

It was also strange that, in late 1990 and early 1991, Harris and Davenport suddenly stopped making arrests, busting traps, and turning in confiscated property. If Maurice Green really had become their snitch, if he had really given them the names of other drug dealers and suppliers, why hadn’t they taken any action? Why hadn’t they at least passed the information along to Vice?

Finally, there was the issue of the officers’ cash flow. FBI agent McSwain, who spent days poring over bank records, testified that Harris’ and Davenport’s spending habits had changed enough during the months of the alleged extortion scheme to suggest that they had to be getting money from somewhere. On a single day in March 1991, Davenport paid cash for four $500 money orders. Although his take-home pay was about $800 a month, he ran up and paid a $300 monthly bill on his mobile phone. He put $3,500 into his wife’s checking account so she could buy a car. With Davenport’s various girlfriends in mind, McSwain checked the sales receipts of jewelry stores near the Zone and found that in the first two weeks of December 1990, he had bought two women’s rings—one for $215 and one for $347.

For his part, Harris had finally paid off the $1,881 he owed in college loans. In the space of six days, he got $3,000 worth of money orders and made a year’s worth of car payments. According to defense attorneys, Harris’ brother, who ran a small landscaping business, just happened to loan him $5,000—a hard story to swallow. (A bank teller later said she remembered Harris’ appearing at her window with $1,300 in $20 bills and asking if she would exchange the money for $100 bills. The teller remembered Harris because he was wearing a T-shirt that read, “Police Officers Do More Than Just Kill People.”)

The jury—five white men, a Native American man, three black women, and three white women—deliberated for four and a half hours before convicting Harris and Davenport. (Angela Elzy was also convicted on lesser conspiracy and extortion charges.) While the officers’ friends and family sobbed in their seats, furious black civic leaders and police officers raced out of the courtroom and denounced the verdict as racist. The police department, they said, ignored aggressive white officers but could not tolerate aggressive black officers. Some black officers announced they would never again diligently pursue drug dealers in Dallas for fear the dealers would conspire with prosecutors to get them arrested.

But for others who knew Harris and Davenport, the guilty verdict spawned a period of soul-searching. How could the officers have been seduced so easily? Maybe they gave in when they realized that no matter how many dealers they arrested, they would never beat the drug trade. Or maybe they began to resent the way they believed their department treated blacks in the community. As Davenport allegedly once told Green, if the police were going to let white dealers go free, why shouldn’t the black dealers get a break as well?

Davenport, the cop who loved the chase, probably overdosed on his newfound power. After the trial, it came out that when he was an officer, he had rented a Lincoln Continental—the same kind of car Maurice Green owned—and slowly drove it through the Zone, granting an audience to yard dogs and dealers at various traps. But what happened to Harris, the good Christian, the one who never seemed too involved in the extortion scheme to begin with? “It was probably Davenport who got the thing started,” says Michael Uhl, the assistant U.S. attorney in Dallas who prosecuted the officers. “Davenport might have collected some of the first payments from the dealers on his own, but because of the policeman’s code of silence not to inform on another cop, Harris didn’t initially say anything. Then, suddenly, Harris found himself too involved, too tainted, to get out.”

Whatever their motivations, when the two men were allowed to speak before sentencing, neither showed the slightest remorse. Davenport, looking U.S. district judge Barefoot Sanders directly in the eye, said he had done everything he could to drive the dealers from the Zone. “If this kind of conduct continues,” he said, “the police will be in jail and the drug dealers will be running the country. ” Then Harris rose. “I went to school to get a degree in criminal justice,” he said, “not to sell dope, not to give dope back to drug dealers.” His voice began to break. “I am the victim. I am a victim of a system that made a mistake, and I can’t accept that. They made a mistake. Somebody destroyed the truth. ” His speech was so passionate, so heartbreaking, that for a moment it was hard not to wonder whether Maurice Green had been lying after all.

But Judge Sanders was unmoved. He gave Harris and Davenport thirty years each in federal prison—a sentence mandated by federal guidelines but one that seemed staggering, considering that the lifelong drug dealers who testified against them got to go free. Under federal law, even with time off for good behavior, the two men will not be released until they reach age 52.

In prison, Swany Davenport washes dishes. Randy Harris sweeps floors. Both men say they haven’t admitted to their fellow inmates that they were once police officers; such information could get them stabbed. Twice a day, Davenport attends church in the prison chapel, while Harris spends his evenings teaching a Bible study class. Harris, who has taken to reading books by Kant and Kierkegaard, says he tries not to think about the Zone. “I talked to my wife the other day,” he says, “and she said, ‘Hey, you need to reach down real far in yourself and forgive these people. They are dope dealers. That’s their lifestyle. You can’t let the injustice eat away at you.’ ” Could it be possible, however, that because of Harris and Davenport, the dealers’ lifestyles have begun to change? Back in Dallas, Maurice Green insists that he has given up drug dealing forever. He says he is working for a car detailing company, earning $26 for every car he cleans. He gave up his trap after the trial because he was worried the “blue suit brotherhood” would take its revenge on him. All over the Zone, he says, cops were telling him, “We’re going to get you one day. ”

“I want to go to work, pay the bills, struggle,” he says, his once-boastful voice now reserved, almost unsure. Green claims he has bought a Bible and wants to become a devout Christian, just like Randy Harris. “Even when I had money and cars and women and people kissing my ass—even when I could do anything I wanted—I wasn’t happy. I now got peace in my heart, and I don’t carry a weapon no more.” If Green is sincere, then Harris and Davenport’s original dream—to get him out of the crack business—has finally come true. Such a transformation would be one of the strangest twists in a story already full of ironies.

A few people who know Green well predict it won’t be possible for him to keep from dealing. “After what he’s been through the last couple of years,” says a law enforcement agent, “he knows too much.” When pressed, Green acknowledges that with the right trap he could make millions of dollars. “I could put together a plan where the police would find dope on no one,” he says. “No one would ever go to jail. No one would ever sell to an undercover agent . . .”

Suddenly, he catches himself and grins. “Naw, just kidding,” he says.

Still, he’s more than willing to go with a reporter to see his trap on Custer one last time. Remarkably, there is no drug traffic on the street, no yard dogs or lookouts. The dealers, perhaps spooked by the location, have moved to the other side of the neighborhood. Children play in the front yards; mothers sit sewing or drinking iced tea on their porches. Some of the residents scowl when they see Green emerge from his new Cadillac Seville, but he just waves. “I’m only visiting!” he shouts.

Staring at his abandoned, boarded-up trap, he is silent for a while, then he finally says, “This was the best house in Dallas. This was the best house anywhere. People would say, ‘Maurice, I hear you’re rolling.’ ” He is silent again for a few more moments, then announces he has to leave; he has to get back to work at the car detailing shop. He does not look happy.

As Green drives away, his former neighbors stand on their porches and watch. Even after he has turned the corner and disappeared, they keep looking, and it is a long time before they relax—not until the sound of his car engine has faded away and the sound of the wind returns, rattling the leaves of the pecan trees.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Police

- Longreads

- Dallas