This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Before she set foot in Taylor high school as a freshman, she had heard about Coach Lynn Stroud. The best-looking coach at the school, she was told. If you get into his biology class, one boy said, “all you have to do is wear a miniskirt and a smile and you’ll get an A.” In his Lee jeans and button-down shirts, Coach Stroud would wander the halls between classes, cracking jokes, slapping kids’ backs, casually throwing his arm around a student. “He came on as the kids’ best friend,” a teenage girl told a police officer in Taylor, a town of 11,000 people 35 miles northeast of Austin. “He tried to fix any problem you had, like grades in another class, or he’d talk to you about your boyfriend problems. He’d let us take his truck anytime we asked him, knowing we didn’t have our driver’s licenses.

The freshman, a pretty blonde and only fourteen years old, had to admit that she was excited when she saw on her schedule that Stroud would be her fourth-period biology teacher. He assigned her a seat in the first row. For a few weeks, everything was normal. Then she got back a test paper with a note. “You did real good,” it read. A few days later, he sent another note. “Hi, you look pretty today.” Finally, shielding a sheet of notebook paper with her arm so none of her classmates would see it, the girl wrote back to Stroud. “How are you today? You look nice.”

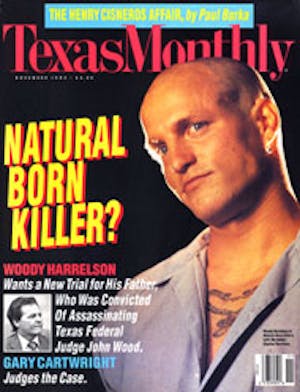

It was the autumn of 1986, and what was about to take place—the seduction of a student by a teacher—would become the basis for a controversial precedent-setting lawsuit that has made its way from one federal court to another and, in October, up to the Supreme Court. The fate of Jane Doe, as the girl is called in court documents, has been debated by some of the country’s most distinguished jurists, all of whom have tried to determine just who is at fault for allowing a teenage student to fall under the spell of a forty-year-old man. In her lawsuit against the Taylor Independent School District, Jane Doe has blamed both the high school principal and the superintendent of schools for not trying to stop Stroud when it became obvious that the coach was making sexual advances. But according to one petition before the Supreme Court, her case is opening a flood of lawsuits by students against their teachers and administrators. School officials nationwide claim that her lawsuit will make them liable for millions of dollars in damages if they do not spend their days tracking down every sexual rumor about what a faculty member might be doing with a student. Taylor school officials insist they did everything they could to protect the girl and to investigate Stroud (who still lives near Taylor and would not comment for this article). “Every time we asked if they were having a relationship, they kept denying it,” says former Taylor High School principal Eddy Lankford. “So why am I now the one who is liable in court for not finding out about it? Why is it my fault that the girl didn’t want to tell anyone?”

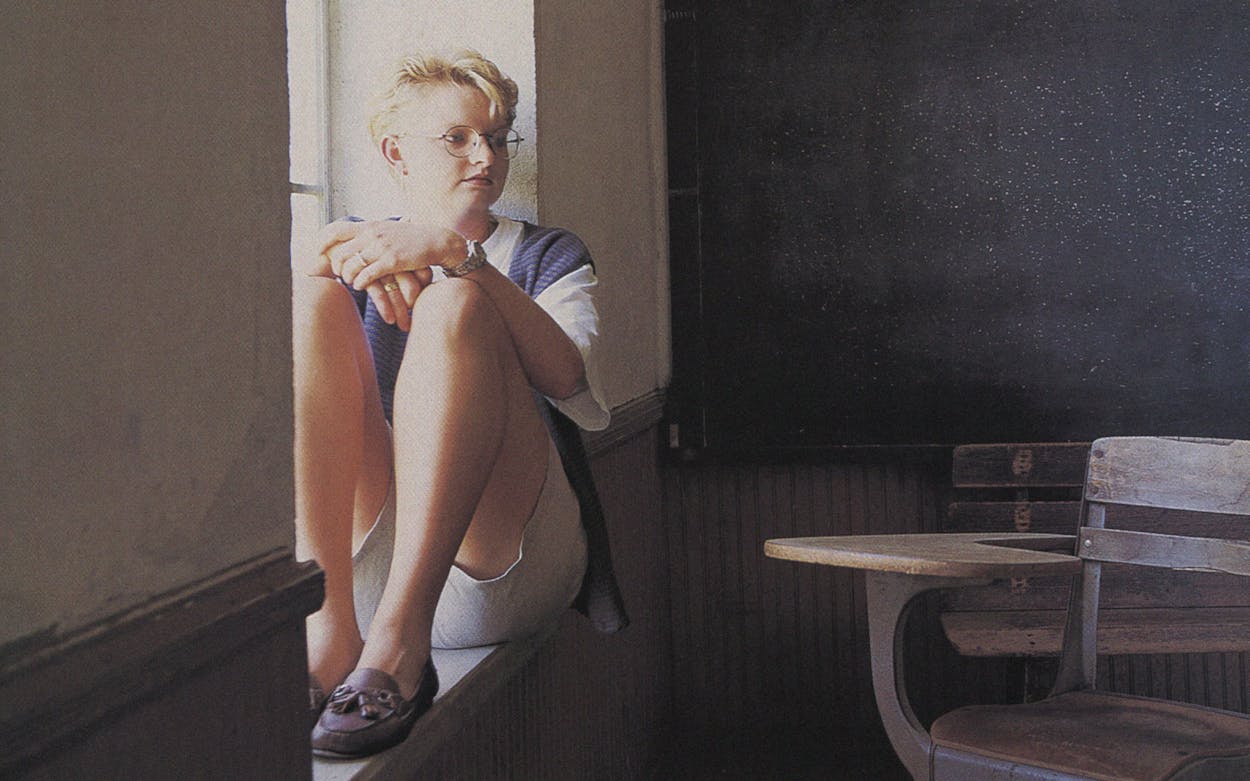

For this article, Jane Doe, who now lives in a Texas city that she requested not be disclosed, has agreed to identify herself for the first time. Her name is Brooke Graham and she is 22 years old, working part-time, and finishing a college degree. “It seems like every time the case goes to court again, someone is ripping apart my reputation,” Brooke says, blinking back tears. “God, I had no idea what I was getting into.”

As in any small Texas town, high school football is a vital part of Taylor’s life. Throughout the eighties, the Taylor Ducks were good enough to make the state playoffs almost every year, and it was hard to find a Taylor citizen who did not know the team’s win-loss record. It was also hard to find anyone who did not know the cheerful Lynn Stroud, the defensive coordinator for the Ducks. At a popular Taylor restaurant, Louie Mueller Bar-B-Q, Stroud would never hesitate to sit down with the townsfolk and talk football. He liked chaperoning school dances, chatting with parents, keeping an eye on the kids. He organized the town’s first chapter of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. Since his 1981 arrival in Taylor, after a series of coaching jobs in other small-town high schools, Stroud had developed a reputation as a coach who motivated more through friendship than by authority. He’d take players camping twenty miles from town on his farm, where he lived with his wife and three children. He worked out with his players. He took them out to lunch on game day. It was not unusual to see Stroud’s pickup in the field house parking lot late at night. Everyone just assumed he was working, perhaps studying game films of opposing teams.

Administrators gave Stroud flowing evaluations for his teaching of freshman biology. They noted in their written reports that he expertly taught students how to locate cells on a slide and the differences between DNA and RNA. They seemed impressed that he subscribed to Omni, Discover, and Science Teacher. But students were telling a different story. At the start of the year, they said, Stroud liked to pick out a few pretty girls and make them his teacher’s pets. The girls were allowed to grade the class’s test papers and put whatever mark they wished in Stroud’s grade book. They didn’t have to do their homework, and they could walk out of class and go to the rest room whenever they wanted. If they wanted a tardy pass so they could be late to another class, he’d write it for them. Meanwhile, Stroud would make the wallflower girls and the boys—well, at least those who weren’t stars on the football team—do all the assigned work.

For the most part, other teachers just sighed when they walked past Stroud’s room and saw girls gathered around his desk. No one had to tell them that the football coaches received a special kind of adulation from the kids. As one Taylor High counselor would later explain, girls at school liked to talk to coaches. It made them feel special. In fact, when two mothers of girls who were in Stroud’s class, but not part of his coterie, protested to principal Lankford about Stroud’s favoritism, Lankford asked the women if perhaps their daughters were just “a little bit jealous” of the girls in the coach’s favored group.

The only faculty member who apparently took the time to complain was the school’s austere, aging, and aptly named librarian, Mary Jean Livingood. On at least two occasions she went to Lankford to report that she had seen Stroud hugging girls in the hallway. She said she had heard from a church friend’s daughter that Stroud was using sexual innuendos in his biology lectures. She said she had caught Stroud with some girls in the photocopy room next to the library. The coach was lifting the laughing girls onto the table and letting them jump into his arms. Livingood called his behavior “child molestation.”

The silver-haired Lankford, a principal in various schools for more than twenty years, had little patience with his nosy librarian. She was always making a fuss about one teacher or another. Lankford told Livingood that all teachers occasionally hug a student. The principal himself had stood in the middle of the gym and put his arms around cheerleaders during pep rallies. Lankford also reminded Livingood that he was the one who had printed a school-spirit bumper sticker that read, “Have You Hugged Your Duck Today?”

“Yes, I know that,” Livingood replied. “But this is not the kind of hugging I’m speaking of.”

Even before Livingood’s complaints, Lankford was aware of Stroud’s reputation for being “too friendly,” as the principal once put it, with high school girls. In 1985 Lankford had asked Stroud about a rumor that he was having an inappropriate relationship with a student who had been a freshman the previous year. Stroud appeared astonished by the question and replied that he and the student only had a close “teacher-pupil relationship.”

Although the explanation was good enough for Lankford, the word around school was that Stroud had treated the girl as his girlfriend. He had been seen placing candy and silk flowers in her locker. He had given her a pair of earrings. It was also revealed in court testimony that he and the girl had secretly swapped notes, with Stroud signing his notes to her, “Love you.” It was so obvious something was going on that Stroud’s favorite football players started teasing him about the new girlfriend. When that girl moved on to her sophomore year, however, Stroud took up with a new freshman. He walked her to class, gave her a stuffed animal on Valentine’s Day, and handed her notes.

Both girls have said in depositions that they were nothing more than close friends of the coach’s. He only helped them with their personal problems, they said; he could talk with them in a way their parents could not. Stroud seemed able to persuade anyone who asked that he was only acting as a caring adult. But in 1990, when a lawyer asked Stroud during a deposition if he had had any sexual contact with either those two girls or with three other former Taylor students who were known to have been especially close to him, he replied that he couldn’t give an answer “on the grounds that I may incriminate myself.” Whatever the circumstances, none of the school’s administrators ever felt the need to investigate the gossip regarding Stroud, beyond asking him about it. Sure, Eddy Lankford made a point to remind the good-natured coach to keep the girls from hanging around his desk. But to accuse him of anything more? Based on what evidence?

From her first day at high school, Brooke Graham, the only child of the well-known Ford dealer in town, was part of the popular crowd. She was on the tennis, volleyball, and basketball teams. She also had plenty of freedom for a ninth grader. Her dad gave her a sky-blue ’66 Ford Mustang to drive to school. She had her own stereo, television, and private phone line in her bedroom. Her parents, Ben and Bridget Graham, were high school sweethearts who had married in their teens, but they were starting to drift apart by the time Brooke entered high school. Ben spent long days at the office, consumed with financial problems at Graham Ford. Bridget was driving to Austin on weekdays to get a degree in interior design at the University of Texas.

Years later, a federal judge studying the events in Taylor asked whether things might have turned out differently if the parents had been around more to supervise Brooke. But the fact was that the Grahams were friendly with Stroud. Bridget had baby-sat his three children one afternoon. She had gone to the high school gym with Brooke and her friends one Sunday afternoon and played basketball with Stroud. Stroud made sure to keep up the friendship. Occasionally he would go down to the Ford dealership to borrow a pickup from Ben to haul the football equipment to out-of-town games. When the Grahams saw him at a local dance, Stroud politely came over and sat at their table, then asked for a dance with Brooke. Not once during Brooke’s freshman year, says Bridget, did any Taylor citizen pass on to her any rumor about Coach Stroud. “Some people have this notion that small towns are full of gossip,” she says. “Well, small towns are just as likely to sweep stuff under the rug. There are times when all of us, me included, just don’t want to believe something ugly is happening.”

Meanwhile, in the classroom Stroud patiently laid his traps to ensnare Brooke. He gave her A’s, even though she never turned in homework or tests. He would take her and her best friends out to lunch and buy them a four-pack of wine coolers from the Jiffy Mart. During football games, while he stood on the sidelines, he would give Brooke hand signs that only she could understand. A flip of his fingers above his head, for instance, meant he thought she was pretty. Smitten with puppy love, Brooke wrote, “I love him, I love him” all over her notebooks. She recorded romantic songs on a tape and gave it to Stroud as a present. “It got to a point where I couldn’t even go out and have a good time with my friends because I was wondering what he was doing,” Brooke says. “Here was this man who everyone in school thought was Mr. Wonderful, and here he was picking me.”

One afternoon in November 1986, as Brooke was leaving the field house after basketball practice, Stroud kissed her on the cheek. Soon, during the five-minute period between classes, they would meet to kiss and fondle in the small lab adjacent to his biology classroom. Stroud swore Brooke to secrecy. If anyone found out, he said, he would lose his job and family. Caught up in the mystery and excitement of infatuation, the vulnerable teenager played along. Brooke became friends with Stroud’s teenage daughter, Marcie—who attended high school in nearby Holland—and would spend weekends at the Stroud home. Brooke and Marcie would usually go to sleep in the living room. Then, in the middle of the night, Stroud would awaken Brooke and take her into an empty bedroom to make out. Both Stroud and Brooke have said that Marcie never acted suspicious about their relationship.

In the hallways of Taylor High, however, the rumors began to grow. Stroud showed up at her volleyball games and tennis matches, standing toward the back, smiling whenever she looked his way. At local dances, he would suddenly appear without his wife, asking all of Brooke’s friends where Brooke was and whom she was dancing with. If any football player asked her out on a date, Stroud would push the player harder in practices than the other boys, making him run more wind sprints. From the coaches’ office, with other coaches around his desk, Stroud called Brooke’s private line in her room to talk. Once, when a concerned assistant coach asked Stroud if he and Brooke were a little too close, Stroud turned on him, pointed a finger at his face, and said, “There is nothing going on. We are just friends.”

Yet eventually, Stroud and Brooke decided to let a couple of her closest friends know about the romance. One afternoon, when they went out to lunch with a girlfriend of Brooke’s, they sat in the back seat kissing while the friend drove Stroud’s pickup. Once, when her shocked girlfriend pulled her aside and said, “God, Brooke, Coach Stroud is as old as your father,” she replied, in the way only teenagers in love can say, “It’s all right. We are destined to be together forever.”

In the spring of 1987, one of Brooke’s closest friends, Brittani Barron, gave Eddy Lankford a valentine she had stolen out of Brooke’s purse. “To my most favorite, prettiest, sweetest, nicest sweetheart in the world!” read the handwriting on the card. “Please don’t change ’cause I need you. I’m in love w/ you—forever—for real—I love you.” Brittani told Lankford that Stroud had written it to Brooke. But Lankford was suspicious about Brittani. She had had her share of problems at home and at school—Lankford had noticed that her name was always on the sign-up sheet on the counselor’s door—and he wondered if this was the kind of thing Brittani would do to draw attention to herself. Maybe she was jealous of Brooke or resentful of Stroud in some way. He told Brittani that he wasn’t sure if the valentine was from Stroud because there was no name on the card.

It would become known among lawyers as the “smoking valentine.” “If Lankford had just done some sort of investigation after that meeting, then he probably could have stopped the relationship before it went any further,” says Brian East, a civil rights attorney in Austin who has represented Brooke for the past five years. What’s more, it seemed every administrator by then had heard something about Stroud and Brooke. Lankford himself, walking past Stroud’s darkened classroom one morning when Stroud was showing a film, saw Brooke huddled on the floor at Stroud’s feet. An assistant principal reported to Mike Caplinger, the superintendent of Taylor schools, that he had seen Stroud engaging in horseplay with Brooke during a basketball game. Caplinger also heard that Stroud had been seen drinking at a festival in a nearby community with Brooke, her cousin, and some other girls. Apparently, Stroud’s wife got so angry at the way he danced with Brooke that she left the festival without him. Caplinger checked out the rumor by calling the mother of one of the girls who allegedly had been there with Stroud. The mother said that no, her daughter had been home sick that day. Instead of checking further and contacting Brooke, Caplinger let the matter drop. The federal courts would later rule that the administrators’ failure to act was an indirect announcement to Stroud that they were willing to tolerate his conduct.

Not many weeks after the smoking valentine incident, Stroud made his ultimate move: He had sex with Brooke in an empty bedroom at the Stroud home while his family was sleeping. In a heart-breaking explanation, Brooke says he didn’t physically force her to give up her virginity. “But he looked at me and said, ‘I love you, and we’re going to be together forever, so why not go ahead and have sex with me?’ I was so afraid of making him mad and losing him, because he really was like a best friend, I guess. I felt like I would lose his friendship if I didn’t.”

Through that spring and into the summer, she agreed to meet Stroud for sex at his home, in the field house at night, and on deserted country roads. Stroud took all kinds of chances with her. The summer after Brooke’s freshman year, he ran a fireworks stand just down the road from the field house. Although company regulations required him to spend the night at the stand to prevent burglaries, one night he slipped away, drove toward his house—where Brooke was staying over with Marcie—parked a few blocks away and then broke into his own home to have sex with Brooke, crawling through a window, waking Brooke, and then leading her into a back bedroom.

Brooke says that at first she didn’t have a guilty conscience about her sexual encounters with Stroud because he kept assuring her that he would leave his wife to marry her. “I knew we’d be able to sit down soon with my parents and tell them, and everything would be all right,” she says. In his deposition, Stroud admitted that he told Brooke many times that he loved her, adding that he saw her “as an equal, not as a student.” When a lawyer asked him what harm there might be in a man his age having sex with a girl Brooke’s age, he replied, “I don’t know.” As recently as last August he told a newspaper reporter, “I’m not the kind of person who went out and molested little kids or that kind of thing. I just had an affair with a high school girl.”

On July 16, 1987, Bridget Graham, needing Brooke’s social security number, opened her daughter’s purse. She saw two school photographs of Stroud, smiling widely in an open-collared shirt. Bridget flipped one of the pictures over. “Please don’t ever change and don’t ever leave me,” the handwriting read. “I want us to be this close always—I love you—Coach Lynn Stroud.”

Later, when Bridget asked Brooke about the note, she said it was just a harmless gesture of friendship. Brooke said the same thing to superintendent Caplinger when Bridget and Ben took her to the school administration building. With her parents out of the room, Caplinger quietly asked Brooke if there had been any sexual relationship between her and Stroud. He said that if she told him, he would make sure Stroud would stay away from her forever. You won’t get in trouble, Caplinger said. Brooke looked him in the eye and said there had been no romance between her and Stroud whatsoever.

Stroud also told the same story to both Caplinger and Lankford. He insisted that he looked upon Brooke as a daughter. Brooke was a good friend of Marcie’s; the Strouds were friends with the Grahams. Stroud said he didn’t care what scurrilous stories the kids at school were inventing about him and Brooke. There was no problem.

The administrators were swayed by Stroud’s explanation. Lankford did suggest to Stroud that he resign to avoid further controversy, but the coach refused. Caplinger told the Grahams that Stroud would be instructed to keep his distance from Brooke. Stroud even showed up unannounced at Ben Graham’s office and said he’d stay away from Brooke, just to shut down the rumors. He also said, “I assure you there is nothing between your daughter and me. You know how kids are. If they get mad at a coach, they start a rumor about him.”

But Bridget wasn’t satisfied. She began floorboarding her Bronco around town, looking for kids who could tell her what Stroud had done. She asked parents of other girls alleged to have been Stroud’s victims to reveal what Stroud had done to them. “I was a viper snake,” she admits. She and Ben argued about the way she was acting. Ben told her to let the school system handle Stroud; she replied that she wanted to get the school system for not going after Stroud. When she learned that Caplinger and Lankford had been hearing stories about Brooke and Stroud before she had discovered the photographs, she demanded to know why she had never been told. “I want Stroud out of here!” she demanded. But Caplinger said that as long as Brooke and Stroud denied having a relationship, the school had no legal power to remove him.

And with that, the administration stopped investigating the case. Lankford would testify that by the fall of 1987—Brooke’s sophomore year—Stroud had changed. His classroom was more disciplined. He ate with the teachers in the lunchroom instead of off-campus with students. Once, going her way, he walked with Brooke to her class. She told him to stop it: She couldn’t have people talking again. But Stroud bought her carnations from the 7-Eleven and began slipping her notes again. One of the notes said he didn’t understand why their relationship had to end, he really did love her, and if she would just give him a little time, he would leave his wife. Soon, Brooke was sneaking out of the house again, meeting him for sex.

In October, while Brooke was at a Young Life meeting, Bridget went through her daughter’s room and found a stash of notes from Stroud. “I saw you at the pep rally,” one said. “You sure look purty!” her hands trembling, Bridget asked Brooke one more time what was happening with her and Stroud. Brooke again said they were just friends, but Bridget wasn’t buying it. Ben took Brooke to their family attorney. Alone with Brooke, the attorney grilled her until she broke down. Sobbing, she said, “Yes, we did it.” The attorney picked up the phone and called superintendent Caplinger’s office. Incredibly, Caplinger had already received another report that very day about Stroud. It seemed the coach had run his hands up and down the bottom of a girl in his biology class. Apparently, he was already moving in on his next victim.

When told he was being suspended from the school pending further investigation, Stroud asked if he might be able to stay around and help coach the team. He was told he had to be out that day. Before he left, he found Brooke in the hallway, grabbed her hands and said, “Don’t worry, we’ll find a way to be together.”

“Oh, God, I’m so sorry,” said Brooke.

Taylor was not ready for the fallout from the scandal. Many people were unwilling to believe that a sexual Pied Piper, cloaked in the raiment of a popular football coach, had been able to operate undetected for so long. They were more willing to believe that Brooke was a local Lolita who had encouraged the secret affair. When the head football coach convened the team in the field house and announced that Stroud would no longer be coaching, most of the players—and one of the coaches—wept. Everyone on the team thought he shouldn’t be fired. One boy wrote Brooke a letter that said, “You’re a slut. Get out of town.” One older businessman in town tried to explain the situation away by telling a father whose girl had also been involved with Stroud, “When these girls start tittin’ up, boy, anything can happen.” Even some of Brooke’s old friends were not ready to pin the blame on Stroud. “I feel that some of it was provoked, because of the way that she was around him, snuggling up to him in the car,” one of the Taylor girls said in a deposition. Brooke’s old friend Brittani Barron said disgustedly, “She let him do it.” After Stroud pleaded guilty to a charge of sexual assault, receiving a six-month prison term and ten years’ probation, some students stopped speaking to Brooke altogether. “I felt that everybody was mad at me because I had taken away their favorite coach,” says Brooke.

She never heard from him again. She did, however, see Marcie one more time. In late 1987, just before Stroud pleaded guilty, the Taylor girls’ basketball team played the team from Holland, where Marcie went to school, and Brooke found herself guarding Marcie. Afterward, Brooke said to the coach’s daughter, “I don’t want you to think our friendship was just a hoax for me to get to your dad. I cared about you too.” After a silence, Marcie gave her a hug, then walked away.

It took Brooke months before she could say out loud that she no longer loved him. According to Bridget, Brooke was wracked by guilt that she had confessed to the family attorney. Once the relationship became public, Brooke felt guilty that she had never tried to stop him from having sex with her. She felt even more ashamed when her parents told her they were separating. Ben and Bridget tried to tell her that their marriage had been falling apart for a long time, but they couldn’t deny that what Stroud had done to their family was the final straw. In early 1988 Bridget and Brooke moved to an apartment in North Austin (Ben gave up the Ford dealership, moved briefly to California, then settled near San Antonio). At her new high school, Brooke told no one what had happened in Taylor. A psychologist who regularly saw her reported that Brooke was going through an “acute crisis.” Brooke was having trouble coming out of her room. Her grades plummeted, and she considered suicide. A furious Bridget, already stunned that Stroud would spend less than half a year in prison, wanted justice.

For a year, Bridget tried to find a lawyer to file a civil suit. “I want heads to roll,” she would say. Besides Stroud, she said, she also wanted to sue Eddy Lankford, Mike Caplinger, and the entire Taylor Independent School District. Attorneys told her that by federal law, school districts and their officials are almost always protected from legal responsibility for the acts of teachers. To win damages from a school district, a plaintiff has to prove that certain civil rights were violated—and the courts had never made it clear that a teacher’s having sex with a student was a specific civil rights violation. Furthermore, the attorneys told Bridget, it would be hard to sue a school district and its officials for sexual misconduct when Brooke consented to have sex in private away from the school. Perhaps, Bridget was advised, it would be better just to sue Stroud and get whatever damages she could.

With each visit to each new lawyer, Bridget took Brooke along and had her repeat the story of Stroud’s seduction. Over and over, Brooke halfheartedly talked about Stroud. She still could not bring herself to blame him. But one afternoon, as she described the way Stroud would talk her into intercourse at his own home, she suddenly looked up and stared at her mother. “I was raped,” she said. She was ready to fight.

The case was eventually taken by Brian East and another Austin civil rights attorney, Nell Hahn. Lankford and Caplinger submitted motions saying they should be immune from the lawsuit. But in an 8–6 vote earlier this year, the U.S. Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit rejected their claims that Brooke was involved in a “purely personal and consensual relationship” with Stroud. The majority opinion declared that this was not a case of casual sex but one of power. Stroud “took full advantage of his position as Brooke’s teacher . . . to seduce Brooke.” The court added that Taylor school officials were so inattentive to Stroud’s behavior that it seemed like they were condoning it. Although the appeals court ultimately dismissed Caplinger from the lawsuit because he knew less and had “responded appropriately, if ineffectively, to the situation,” some of the justices characterized Lankford’s inaction as “deplorable.” The court found that school officials can be held liable if they show “deliberate indifference” to the civil rights of a schoolchild. An outraged Lankford appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, claiming that if the lower court rulings were allowed to stand, then all public school officials would be “responsible for the private lives of school employees and students, all day, every day, year round.” Many state and national school organizations—such as the Texas Association of School Administrators—filed amicus briefs with the Supreme Court agreeing with Lankford’s arguments. But in October the Supreme Court rejected Lankford’s appeal, siding with Brooke’s right to sue. Attorneys on both sides agree that the ruling gives students substantial legal power to sue their teachers and administrators. Already, according to one document before the Supreme Court, Brooke’s lawsuit has become “a significant catalyst in the explosion of sexual abuse litigation that has been brought against public schools and school officials throughout the country.”

According to some sources, the Taylor Independent School District is arranging a settlement with Brooke, and the case will likely not go to trial. Lankford still lives in Taylor but has taken early retirement. Caplinger has quit his job as superintendent and moved out of the district. And Stroud remains on the family farm outside of Taylor. He works in hospitals as a respiratory therapist, and his wife, Pat, who has stayed with him throughout the ordeal, says he is a different person. He has gone through extensive therapy, she says, “and it’s now time for people to just leave us alone. Our children don’t need to be burdened with this bad publicity. We need to move on with our lives.”

Brooke Graham is trying to do the same thing. According to a report by her psychologist entered into court records last year, “Brooke still feels extreme shame, and it is difficult for her not to blame herself. . . . She has a great deal of difficulty trusting people, and rarely allows herself to get emotionally close to others.” But Brooke says that she knows she’s getting better. Sitting on her couch in shorts and a T-shirt—not looking much different from her high school photographs—she says, “Just to know I’m winning in court gives me some sense of relief, don’t you think?”

As she leans back in the couch, her arms crossed, her face focused on her lap, she says that not a day goes by without her thinking about Stroud. “I still see him in my sleep,” she says. “In this dream I have, I’m in a pickup truck in a grocery store parking lot, and suddenly there he is, coming up to the driver’s-side window. I try to get the truck in gear, but it won’t move. He starts banging on the window. And I keep pushing on the gears, trying to get the truck to move. It’s crazy. I’m stuck. I start screaming. He keeps banging and banging.” Brooke finally raises her head. “When I wake up,” she says, “I can still hear the banging.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime

- Austin