There is a quiet, inviting light in the gaze of Elmo Henderson, the look of a charming man who knows he’s charming. He’s clearly from another time, still tipping his hat to the ladies, peppering his speech with “ma’am’s” and “sir’s” and “oh, no, after you’s” and insisting on eating every dish with a knife and fork—french fries, hamburgers, tacos, everything. He’s 69 years old, an age when people expect nothing more from him than a story and a smile. That is, after all, the only real currency that an old homeless man like Elmo has, and it’s how he’s made his way for quite a while now. No conversation gets far before he brings up the night in 1972 when he fought Muhammad Ali in an exhibition in San Antonio and all the unlikely doors that that opened for him.

“I was in Fort Worth from Reno to see the family,” said the onetime light-heavyweight champion of Texas, “and I picked up the morning paper one day and it exposed that Ali would be in San Antonio that Tuesday putting on an exhibition against some local fighters. I said, ‘Let me go to San Antonio and congratulate Muhammad on coming back to the ring.’ Well, I didn’t know nothing about it, but one of the fighters for that night was a kid from Mexico who couldn’t get his visa to get in the country. So when I went to where Ali was staying, across from the Alamo, I ran into the promoter on the bottom floor, and he says, ‘Good morning, Elmo. How would you like to put on an exhibition with Ali tonight?’ And I okayed it. Then, when I’m signing the contract, Ali comes up and taps me on the shoulder and says, ‘Get up and let me see what you got.’ I said, ‘Get away from me, sucker. I’m too fast for you!’ And he popped his eyes and got away.”

We were sitting in an East Austin Mexican food place called Juan in a Million, and Elmo looked closer to fifty than seventy. His ash-colored hair is always hidden by a hat, what he calls his “lid,” and on this August morning he’d chosen a black straw fedora with a small feather in the band. He wore a short-sleeved button-down shirt, white with black pinstripes, that he tucked into black, pleated Bermuda shorts. The only hints at his age were sheer black dress socks and clean white tennis shoes below bony old knees. The restaurant was a block from the halfway house where Elmo had lived for the spring and summer, but in his mind we’d moved considerably farther, to a time when boxing mattered to people other than ring nuts and gamblers. The ring then was the domain of true lions, champions like Ali, Frazier, and Foreman, heroes people felt they knew, not vague figures who came out each year and a half for a pay-per-viewing. Once upon that time, some fight fans even knew the name Elmo Henderson.

“About seven-thirty that evening, I cranked up and made it to the dressing room at the coliseum. I got into my togs, and a guy came in and asked for me personally, Elmo Henderson. He said, ‘You first.’ Here I am, thirty-seven years old, and they wanted me first, for three rounds with Ali. So I put my robe on and ran out there. I didn’t walk. I ran. And I got up in the ring, looking at the fans, you know, putting the game on Ali, and the ref motioned us into the center. I’m looking down, and what’s going through my mind is, ‘I’m first, so I guess the old man gets the honors.’”

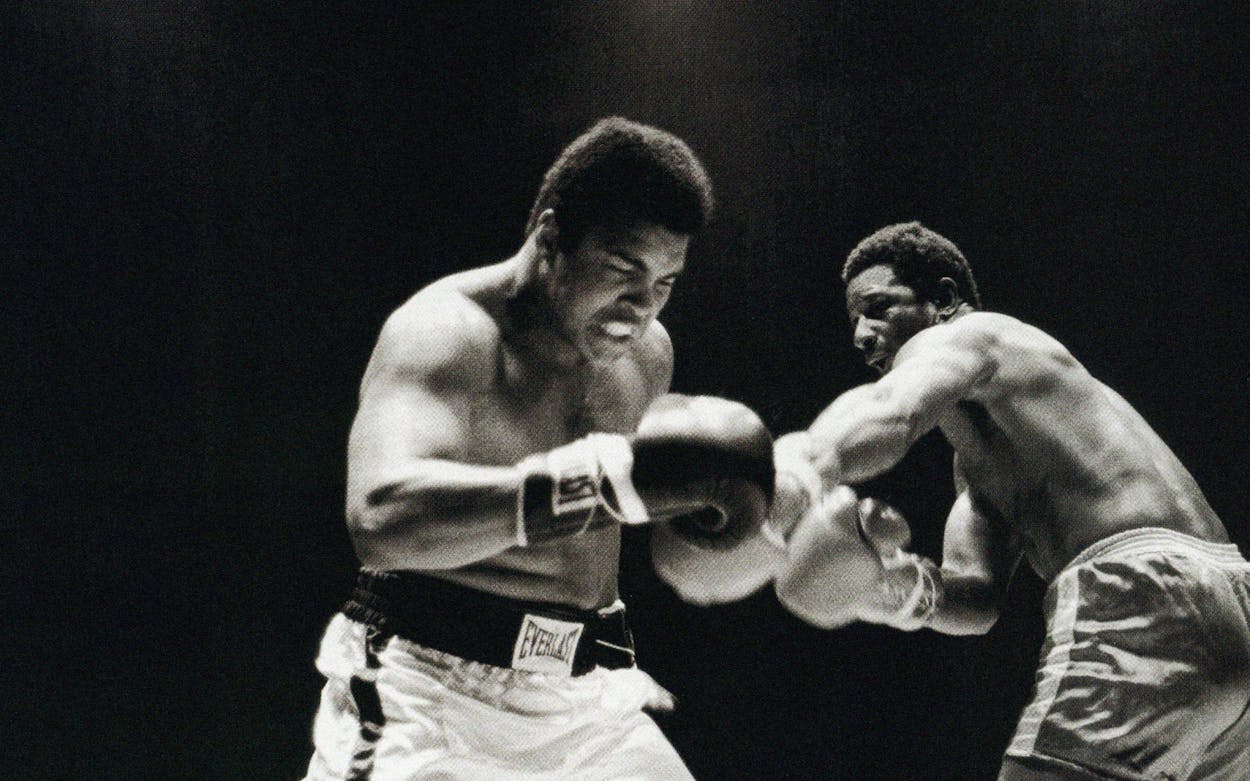

He pushed his taco plate aside and spread out a folded-up, Xeroxed copy of an old newspaper photo on the table. His hands are heavy and broad, with the joint at the bottom of his right thumb shoved back to his wrist, a trophy of a fight that is harder for him to find in his mind than the one with Ali. “That’s me and Ali,” he said, pointing at the picture.

“When they rang that bell, I came out like a speedball: Brr-rrrr-rrrr-rrrr, everything a blur, and then the first round was over. On to the second round. I didn’t run out. I took my time. Moving. Ali was throwing jabs, and I moved away from one and threw a right hand and—bam!—that put him down. So the referee runs the count to eight, and instead of going on, he went back to one. Then he brought it up to eight again and stopped. I just pushed him away and said, ‘Hey, if you want to let him up, let him up.’ I said, ‘Get your ass up, kid! You ain’t hurt!’ Then the bell rang and the referee came to my corner and said, ‘Elmo, that’s all.’ But he didn’t raise my hand or give me my rights. He just put me out the ring, and they went on with the rest of the bouts.”

Elmo paused to watch me soak it all in. Then he rolled through the ways that that night had redirected his life. In the dressing room after the fight, Ali’s headlining opponent, Terry Daniels, asked him to spar out in Reno. A couple months later, he took a similar job with George Foreman and then accompanied Foreman to Zaire for the Rumble in the Jungle with Ali. In Africa Foreman appointed Elmo cheerleader of his entourage, the designated counterbalance to the histrionics of Ali. He made enough of an impression there to merit a section in Norman Mailer’s account of the fight in Playboy, which, in turn, became the basis of a million-dollar libel claim after Elmo took issue with the way he was depicted. In 1977 a Corpus Christi jury awarded Elmo $105,000, making him, at least in his telling of the story, the first black man ever to win a libel suit against a white man.

Most of that information was just a Nexis search away. But the exhibition in San Antonio didn’t show up in the books, not even in a career like Ali’s, which has been chronicled down to the round. I studied the newspaper picture. It was the reason I’d found Elmo in the first place. A doctor friend of mine had given him my number after Elmo had been in for some malady or another. When the doc asked him for identification, Elmo told him this story and pulled out this picture. It was a twentieth-generation copy of a copy and mostly black blur. All that was discernible were two figures, one in a pair of white Everlast trunks. At some point in the past, Elmo had scrawled “Alie” on the trunks. He must have repeated the story more times than he could remember, so many times that it seemed to have become all he remembered.

“Ali was looking for a jab, so I evened up on him and shot him a right. It was a good one. Even I saw lightning.

“And that’s about it, sir.”

Nobody sets out to be a sparring partner. It’s a temporary state, a function that signals a stage in a boxer’s career, hopefully the beginning, when he is trying to pick up fights and make his name. Less frequently it comes at the end, when the fights have faded away but a boxer knows no other life. Elmo Henderson knew sparring on the way up and on the way down.

He got his first taste of the ring in 1954. He was an easygoing nineteen-year-old then, a ninth-grade dropout from Fort Worth’s Stop Six neighborhood who was cleaning sheets of metal in a steel mill when a friend with an upcoming boxing match asked him to spar. The gym felt right. He was a natural athlete who enjoyed a little dope but hardly ever drank, and even though he was a spindly six-two, 145 pounds, he was quick enough to keep from getting hurt. When he found out his friend would be paid for the fight, Elmo heard his calling.

He sparred around Dallas and Fort Worth, taking fights where he could. The Ring Record Book shows four of them in the fifties, most notably an eight-round loss on points to Curtis Cokes, who went on to hold the world welterweight title from 1966 to 1969 and is now in the International Boxing Hall of Fame. In 1961 Elmo began a year in Huntsville for stealing a television set out of a truck, but he boxed as much as he could in prison and got released early, he says, after defeating the Texas middleweight champion in a match at the Walls.

He’d heard from a murderer he’d sparred with in prison that Corpus Christi was a good fight town, and that’s where he landed upon his release, working as a longshoreman and fighting every three months or so. He’d finally filled out some, fighting as a light heavyweight at 165 pounds. His height gave him an advantage over most of his opponents, who had to work past a stiff left jab to get near him. Since he always fought preliminary matches, he didn’t get much ink in the Corpus paper, but whenever he was mentioned, he was described as a flamboyant crowd favorite. “I was always talking,” says Elmo, “always bragging about what I could do and what I had done.”

His skills developed too. Ronnie Wright, a Fort Worth fighter and trainer, remembers Elmo’s best weapons being that jab and a strong right cross: “I never knew if he grew up boxing or was just a natural fighter, but he would sit there and drop his hands, and you could throw a straight right at his jaw and he’d just move his head out of the way. He wasn’t afraid of anyone.”

In December 1963 things started to click, and Elmo ran off a string of six straight wins. He was fighting as “the Professor” now and wore a cap and gown into the ring instead of a robe. In November 1964 he won the state title by knocking out Austin’s Benny Bowser in the second round. Suddenly he was appearing simply as “Elmo” in sports-page headlines. “I was a celebrity,” he says. “People would buy me dinner. And the ladies were sure glad to be in my company.” But his reign was short, and the Corpus Christi Caller-Times was less than generous in its description of his rematch with Bowser a year later: “Only in the second round was there any sustained action to excite the small crowd of about 650. In that one, Henderson caught Bowser off-balance with a right hand and knocked him down. Bowser was up immediately . . . and proceeded to jar Henderson with right hand smashes to the body and left hooks to the head.” Elmo lost his title on a split decision.

He left Corpus Christi after that, bouncing between relatives’ couches in Reno and Oakland and, although he was old for a fighter, at 32, taking more fights. In 1967 he had six of them in ten months’ time. After a violent bout in San Diego that August, the California Athletic Commission demanded that he undergo an exam to see if his brain had been damaged. Instead he jetted off to New Zealand to fight Bobby Dunlop, a young comer with a 26–3 record, just two weeks later. Miraculously, he knocked Dunlop out in the fourth round, earning himself an eighth-place world ranking. But three and a half months later, he met Dunlop for a rematch in Sydney and looked like he was sleepwalking as Dunlop won a brutal eighth-round KO. When the news of the fights got back to California, his license was suspended indefinitely.

Elmo’s career was interrupted again, in 1968, when the Fort Worth police caught him with a couple of joints. After a second year in Huntsville, he moved back to Reno, where, carrying an additional twenty pounds and now 35 years old, he fought as a heavyweight. He beat a contender in Mexico and earned a fight in Lake Tahoe with Earnie Shavers, considered by some to be the hardest puncher ever. Elmo went down in four. He had two more fights in Lake Tahoe, in 1972, but after that Nevada wouldn’t license him anymore either. State law said that, with limited exceptions, no one fought past the age of 36. That October, all he wanted was a sparring job when he went looking for Ali.

I happened to be in the office when Elmo called one Sunday soon after our breakfast. “This is Henderson,” he said, and without waiting for me to say anything, he went on, “and I’m leaving the place here and I need a ride.”

Ten minutes later, I was at the halfway house, where Elmo was waiting out front, with everything he owned secured in five small white garbage bags. It turned out that by “leaving” he meant “moving on,” and while I tried to talk to one of the counselors about what exactly was happening, Elmo directed another to put his things in the back of my Jeep. Then he looked at me and said, “Let’s hop in the buggy and get on.”

As we rolled to the end of the parking lot, a guy sitting on a metal folding chair in front of his room hollered, “So long, Champ!” But Elmo fiddled with the seat belt and didn’t look up. Before turning into the street, I asked him where we were headed. He said he didn’t know.

“What are we going to do with your stuff?” I asked.

“Well, I guess we better put it in storage.”

“Where’s storage?”

“I don’t know. Where is storage? Let’s drive around and see what we find.”

So we drove. The doors and the roof were off the Jeep, so Elmo bent one long arm to hold his fedora on his head as he directed me through much of East Austin with the other. He said he had some family in town, people named Denman, but he wasn’t sure where they lived. He had me stop in front of a house he thought he remembered, but when he knocked on the door, no one answered. He looked over the back fence and called out, “Henderson. Henderson,” but got no response. He said he’d check with the neighbors and walked across the yard, still calling, “Henderson.” I looked over my shoulder at his things in the backseat and then looked up to see him taking a pee next to the neighbor’s house, still calling, “Henderson.”

We stopped to get gas at a station on MLK Boulevard, and Elmo got out to talk to a man filling an old brown Impala at the next pump. I heard him ask if there were any boxing gyms in the area and then proceed to tell the man how he’d broken Ali’s jaw. Back in the car, we drove by a halfway house on East Twelfth, where a man said Elmo could have a bed if he was willing to stay a full six months and get right with Jesus. That didn’t strike Elmo as the answer, and we kept on. He had me stop every time we saw a black person on the sidewalk. “Do you know any Denmans?” he’d ask. They’d all look a little surprised and answer no.

Reluctantly, Elmo agreed to apply for a bed at the Salvation Army shelter about a block from my office. A lady who worked there said he could get in but that he’d get only one small locker and would have to place his things elsewhere. That turned out to be my office, which was fine. It would help him out and guarantee that he would keep in touch.

Elmo’s role in the Rumble in the Jungle was simple. George Foreman took six sparring partners to Zaire in 1974 to help him train for Ali, and he’d go into the ring with three or four a day. Some of the guys were there because they hit hard, others for their foot speed. At 39, Elmo could still do some of both, but his chief job was to ape Ali. He danced, he jabbed, he took punishment at the ropes. “Elmo was unorthodox,” says Stan Ward, one of the other sparring partners. “He would throw punches up and over, around the side. And he had the gift of gab, like Ali, always something like ‘Is that all you got?’ that would elicit an emotion from George, maybe humor, maybe anger.” Foreman’s brother Roy said the fighters would rotate, taking days off, but Elmo was in there every day: “Elmo used to talk so much noise that George liked to get him in the ring and pop him.”

Getting popped by George Foreman was no small deal. By the time the fight was booked with Ali for October, Foreman looked like he might be the greatest champion ever. He was strong, his chiseled frame the product of chopping down trees with an ax each morning and harnessing a pickup to his shoulders and pulling it around his California training compound each afternoon. And he had a vicious reputation that fight fans today, even with a young Mike Tyson as a reference point, could never imagine. He hit fighters on their way to the canvas. He beat his sparring partners unconscious. “Hell, I’m paying them” was his justification. But the odds were on Foreman chiefly because of the startling way he had won his two biggest fights: his tragicomic two-round and six-knockdown dismantling of Joe Frazier to win the title and a similarly decisive second-round KO of Ken Norton, the last furious punch coming when Norton was almost flat on his back. At that time, Frazier and Norton were the only two men to have beaten Ali.

The Rumble in the Jungle was the first masterstroke of a young Don King, who orchestrated the fight as a coming-out party of sorts for the new country of Zaire, recently liberated from longtime Belgian occupiers. It was a spectacle that held the attention of the world. But there was a morbid what-if-Knievel-crashes element to the fascination. Many observers worried that Foreman might actually kill Ali. It had been seven years since Ali had been stripped of his title for refusing to answer his draft notice, and since being reinstated in 1970, his four-year odyssey to win it back had been up and down. Sportswriters assumed he was acting out of fear when he went to work at psyching out Foreman before the fight, trying for a mental edge, the only one he might find.

“We’re landing in Zaire at about two in the morning,” remembers Ali’s business manager, Gene Kilroy, about the challenger prefight, “and right before we get off the plane, Ali looked at me and he said, ‘Gene, who don’t they like over here?’ I said, ‘I guess white people.’ Well, Ali laughed and said, ‘How can I say that George Foreman is white? With you standing next to me? Somebody might think you’re George Foreman and shoot you with a poison dart. Who else don’t they like?’ I said, ‘Belgium.’ He said, ‘That’s good.’

“So we walked out and it was pitch-black. You couldn’t see anybody out there, but you could hear them. ‘Ali! Ali! Ali!’ So Ali put his hands up for everybody to be quiet. Then he said, ‘George Foreman’s a Belgian!’ And the crowd went wild. They started yelling, ‘Ali boma yé! Ali boma yé!’ I turned to our translator and asked, ‘What are they saying?’ and he says, ‘That means “Ali, kill him!”’”

For the sullen Foreman, any advantage that came with being the champion was lost. By the time he cut his right eye while sparring, postponing the fight a month, he was thoroughly bugged by the overwhelming response to Ali. “George could not understand it,” says Leon Gast, whose film about the fight, When We Were Kings, won the 1996 Oscar for best documentary. “But where Ali was out and all over, meeting people, signing autographs, always accessible, Foreman was in his compound the whole time.” So Foreman decided to change his tactic by countering Ali in the war for Africa’s affection and positioning someone opposite the butterfly-and-bee routine of Ali and his wild-eyed sidekick, Drew “Bundini” Brown. He turned to the loudest mouth in his camp, Elmo, taking him out of the ring and giving him a bullhorn and a short script to get everybody’s attention—“Oyé! Oyé! The champion George Foreman! Foreman boma yé!”—to which Elmo added a bit of his own poetry: “The flea goes in three! Muhammad Ali!”

That’s the image of Elmo that the boxing world took home, of a tall, lanky fighter in brightly striped street clothes, constantly screaming, “Oh yeah! Oh yeah!” (Elmo seems to have misunderstood his instructions.) Wherever Foreman went, there went Elmo, in the hotel lobby, around the hotel pool, in the gym, at the weigh-in. “Oh yeah! Oh yeah!” In his autobiography The Greatest: My Own Story, even Ali remembers hearing “Henderson, The Champion’s chief clown,” screaming at ringside during the fight. In Norman Mailer’s Playboy story, the one that would get him sued, the Pulitzer prize–winning author described Elmo as looking “like some kind of lean wanderer in motley—the long stride of a medieval fool was in his step . . . Oyé . . . Foreman boma yé. . . And Foreman . . . seemed confirmed in his serenity by the power of the other’s voice, as if Elmo were the night guard making his rounds and all was well precisely because all was unwell.”

And of course, nothing was well with Foreman. Ali pulled off the greatest upset in sports history. The legend of that night is of Ali against the ropes, letting Foreman punch himself out; of Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee, begging him to dance; and Foreman’s corner letting big George charge on. “I had spoken to George several times before the fight,” says Elmo now. “I said, ‘Keep Ali in the center of the ring.’ And during the fight, I jumped up in his corner and told him again. But a group of guys grabbed me and pulled me back. And they let him follow Ali to the ropes and fight that bullfight.” Foreman’s cousin Willie Carpenter, who helped coordinate the sparring partners in Zaire, says Elmo is right to claim a place in the legend. “I think Elmo jumped up in the corner and tried to give George some instruction,” he says. “I don’t think George cared for that too much. We asked Elmo about that afterwards, and he said he’d probably just seen something we hadn’t seen.”

With his bags in my office, there was no need to worry about Elmo staying in touch. He kept in such steady contact, in fact, that you could tell the weather by it. If it was cool out, as parts of August and September unseasonably were, Elmo would just call. I’d get to work and find a voice mail left by someone with a cell phone that Elmo had encountered on the street and persuaded to call my number. I’d hear a voice say, “It’s an answering machine,” and then Elmo’s voice in the distance, “Tell him ‘Oh yeah’ called.” Pause. And then a confused, “Um, ‘Oh yeah’ called,” and a click.

But on hot days Elmo would stop by. A couple times I returned from lunch and found him asleep in a chair in the lobby. I’d walk him to my office to let him check on his stuff, and on the way, he’d hold each door for anybody passing through. “Good afternoon, ladies,” he’d say. “Don’t mind me. All I did was whup Ali.” That was his way. One day I found him in the alley behind the Salvation Army with four men sitting on the curb in front of him while he paced back and forth, pointing at his newspaper clipping, explaining how he’d beat up on Ali.

Occasionally we’d eat at Mike’s Pub, an old burger place near my office, where I tried to get Elmo to talk about life now. He said he’d been living off monthly social security checks of $340. The past four years or so he’d been in Vallejo, California, living with a longtime girlfriend and their seventeen-year-old daughter, but he said he didn’t know their phone number. The mailing address he gave me was for a street that didn’t exist. For twelve years before that, he said, he had lived rent-free at an apartment complex, collecting for the landlord.

But Elmo wanted to talk about boxing. He steered the conversation to his protégé, a kid named Adrian Havas who fought for Elmo’s Oh Yeah Boxing Club, in Reno, in the late seventies. When I talked to Havas, he remembered listening to Texas R&B tapes in Elmo’s Bonneville on long drives to fights, with Coach Elmo decked out in bright plaid leisure suits and matching hats. Elmo booked the fights in places Havas might otherwise have avoided, like a Carson City prison. But there they were, the white sixteen-year-old son of a well-heeled car dealer, fighting a convict twice his age, while this aging club fighter in plaid raced around the ring trying to inflame the crowd. “I’d shout, ’The flea will go in three,’ ” said Elmo. “That was my ballyhoo, even in Reno.”

“Elmo had taken a lot of punches through the years,” said Havas, “and when I was sparring with him, sometimes I connected. But he never hit back. There were many times I wished I had seen him in the ring for real, because it’s such a brutal place, and he never seemed to have that killer instinct.”

Shockingly, Elmo did fight during that period. In 1979 Montana granted him a license to box despite the suspensions in California and Nevada, and he was knocked out in the fifth round by Pinklon Thomas, a 21-year-old undefeated fighter who would win the heavyweight championship five years later. Elmo was a day away from his forty-fourth birthday.

Elmo didn’t have many specifics about what had happened after that, not even in the recent years. He said he’d found the halfway house in Austin by chance: “I was walking down the street and there it was.” Even though he didn’t meet its recovering-addict or fresh-out-of-jail requirements, they let him stay. But when his behavior grew erratic—a friend of his told me that Elmo had been going to the bathroom in places other than the bathroom—he was asked to leave. All Elmo would say was, “A problem developed with a couple of the other inmates.” So now he was concentrating on the chore that had brought him to Texas. He said he’d come to get some money from an attorney. He’d decided that since the Mailer jury had awarded him $105,000 and his take had been far less, his lawyer must have kept the rest.

“Foreman had a sparring partner named Elmo Henderson,” began the chapter on Elmo in Mailer’s piece on the fight in Zaire, “once Heavyweight Champion of Texas and not too recently released from Nevada State Hospital for the insane.” The section came at the end of the first installment of Mailer’s two-part account, taking the pre-Rumble hype to a fevered pitch with Elmo and Bundini Brown jawing in the Kinshasa hotel lobby, leaving off at a faux cliff-hanger on the eve of the fight. Publication of the story was an event in itself; Mailer was a bona fide celebrity author, and his take on the fight was bulleted in bold on the magazine’s cover. Playboy printed seven and a half million copies of the May 1975 issue and sent them to 57 countries; more than 260,000 copies sold in Texas alone. One of those made its way to Elmo, who was working as a bouncer at a Corpus Christi gay bar. The throwaway line about the mental hospital leaped out at him. Whatever his reputation and however his appearance, that line was a lie.

He contacted a Corpus Christi lawyer named Bill Nutto. Once a tank commander under General Patton, Nutto gloried in a good fight and getting dirty on behalf of an underdog. He’s 83 now and long-retired but ever the gladiator; if you get him on the phone in the afternoon you’ll hear him fire an F-bomb every third word as he screams over a radio broadcast of Bill O’Reilly. Like a lot of old attorneys, Nutto remembers every detail of his greatest victories.

“A turning point in the trial? Ha!” he says. “We didn’t need one. Mental hospital? They published it, and it wasn’t true!”

But Nutto admits to some obstacles, chief among them a client who had twice been to prison and never held a steady job. In the transcript to his July 1975 deposition, Elmo was typically charming but occasionally incoherent. He attributed much of the adversity he’d encountered in his boxing career to a fight establishment cover-up of his San Antonio knockout of Ali. And there were moments of pure Elmo, as when he tried to sell defense attorney David Krupp one of the gold-plated golf putters he was hawking for a friend.

There was also the little matter of damages. It wasn’t enough to prove that Elmo’s feelings were hurt, not if he was to collect any real money. Nutto had to show that Mailer’s statement had somehow affected Elmo’s ability to make a living. But at forty years of age, Elmo was going to have a hard time proving he was in line for the $5 million payout of an Ali or a Foreman. Despite a conveniently scheduled fight in Corpus on the night of Elmo’s deposition, in which Elmo made short work of a no-name opponent, Krupp, who sat ringside as Nutto’s guest, was not impressed. When Nutto offered to settle Elmo’s million-dollar claim for $24,000, he declined.

In front of a hometown jury, the trial went Elmo’s way from the start. At voir dire, when Nutto was questioning 36 jury candidates, he asked who among them had heard of Norman Mailer. Two people raised their hands. When Nutto followed with, “How many of you have read Mailer’s work?” both panelists put their hands down. Mailer, who chose not to be interviewed for this story, has told friends that that moment was more degrading than losing the trial. “Corpus Christi . . . what a terrible f—ing town,” Mailer’s account usually begins.

Nutto delighted in the battles with Mailer, Krupp, and even Judge Owen Cox, a conservative jurist who wore a bow tie around a neck that old Corpus lawyers recall as decidedly stiff. Nutto particularly enjoyed introducing the issue of Playboy as evidence in Cox’s court. And when Nutto picked up a copy of Cosmopolitan that his secretary was reading, he was thrilled to find an article about Mailer in which he had admitted to smoking marijuana. On cross-examination, Nutto asked Mailer about the statement. “The defense objected,” says Nutto, “and Judge Cox said, ‘I’m not going to let that sit,’ and sustained it. So I apologized. But the jury now knew my theory that Mailer had got a little potted up and hallucinated the whole thing.”

Things got worse for Krupp. Mailer was not sympathetic on the stand. Elmo, on the other hand, was, politely answering condescending questions from Krupp like “Did you ever discuss poetry with George Plimpton while you were in Zaire?” (Elmo’s answer: “Nope.”) Krupp’s gamble that Elmo would appear crazy enough to justify Mailer’s charge didn’t pay off. Nor was his case helped when, on Mailer’s way out of the courtroom to catch a plane back to New York, some jurors heard him tell Elmo, “Well, I guess we owe you some money. It’s just a matter of how much.”

At closing arguments Nutto went for broke. “Ladies and gentlemen, they’ve portrayed the life of a boxer as one of glamour,” he said. “But if they’d written the truth, they’d have written about guys who get up in the middle of the night to do roadwork, then go to a swelteringly hot gym to punch a heavy bag, spar, do more roadwork, and go to bed. If the defendants had written that, it would have been absolutely true. But it would not have sold magazines.”

“When Nutto talked about the roadwork,” remembers Krupp, “he started jogging slowly up and down the length of the jury box. What was I going to do, stand up and shout, ‘Objection, Your Honor. Counsel is jogging’?”

The jury bit. On November 16, 1977, they awarded Elmo $5,000 in actual damages but $100,000 in punitives, creating headlines in papers as widely read as the New York Times. But Judge Cox deemed the amount excessive and ordered that either Elmo would accept $22,500 or the case would be tried again. Having had enough of Nutto, the defendants chose to pay an undisclosed amount somewhere between the judge’s number and the jury’s. Nutto, still a dutiful officer of the court, refuses to say how much. Elmo says he received $40,000.

“The next time I saw Elmo,” says Nutto, “he drove up in a big, used Thunderbird. He said he was on his way to New Orleans to become a sparring partner for Leon Spinks. It was just before Spinks’ second fight with Ali.”

Dr. Barry Jordan is the medical director for the New York State Athletic Commission and the director of the Head Injury Service at the Burke Rehabilitation Hospital, in White Plains; he is generally regarded as the world’s foremost expert on the effects of ring-related head trauma. He’s no boxing apologist but a true fight fan who happens to be supremely in tune with the dangers of the ring. As an advocate for boxers’ safety, he’s widely respected and extremely well spoken. When I told him that Elmo had fought professionally from the age of 19 to 44, he had a one-word response: “Wow.”

With the caveat that an exam of a patient and a phone call with a third party are two radically different things, Jordan outlined what 25 years in the ring can do. The chance that a boxer will suffer chronic brain injury increases dramatically as his career wears on, which makes sense, given the way advancing age, diminishing skills, and severe beatings feed off one another. The damage is to the frontal lobes of the brain, and typically the injury results in diminished motor function and cognitive abilities and in behavioral changes. The first two effects show up as slow or stiff movement and memory loss. And then there’s the decrease in judgment; a person becomes disinhibited and loses common sense. He talks to people he’s never met as though he’s known them for years. When I told Jordan that Elmo had a habit of urinating where he shouldn’t, the doctor had the same one-word response: “Wow.”

If Elmo is suffering from that kind of injury, part of the shame is that it didn’t have to happen. State athletic commissions are charged with making sure fighters are physically able to fight, and fully five of them, including Texas, granted Elmo licenses after California suspended him in 1967. That wouldn’t happen today. In 1996 Arizona senator John McCain pushed the Pro Boxing Safety Act through Congress, which requires that states honor one another’s suspensions and that fighters carry a boxer’s ID card to make suspensions easier to track. McCain also has legislation pending now that goes even further, establishing a federal boxing commission that would maintain a national medical database, so that an MRI exam showing the condition of a boxer’s brain in California early in his career could readily be compared with one taken in Texas years later.

But Elmo needs protection now from something other than better fighters. Unlike most pro sports, boxing offers no pension. Support of old fighters comes from the generosity of other, more-successful boxing figures. That’s why even Don King and Mike Tyson get good press every now and then, showing up in the news helping some forgotten, broken-down pug. But too often that goodwill comes too late, like the tombstone Tyson bought this summer for former welterweight champ Kid Gavilan, who’d recently been buried in a pauper’s grave in Florida.

In most states, Texas not among them, private organizations pick up the slack. The most successful has been the Retired Boxers Foundation, in California. It has a $25,000-a-year budget, the money coming from wealthy fight fans and an admirable deal with the Golden Palace online casino, which gives 2.5 percent of its endorsement fee whenever a boxer wears its logo on his back for a televised fight. The RBF has paid for old fighters’ chemotherapy treatments, bought them decent clothes to wear when they sign autographs at memorabilia shows, and helped with rent payments. There’s one boxer in Philadelphia who can’t remember to pay his light bill. RBF founder Alex Ramos calls him at the end of each month to remind him to cut a check.

Jacquie Richardson, the RBF’s volunteer executive director, said that in a case like Elmo’s, the RBF’s medical board would provide free tests to determine if boxing injuries are at play. If they are, his social security benefits could increase, Medicare could help pay for drug treatment, and he would likely qualify for an assisted-living allowance. “We’ve got another homeless fighter under a bridge on I-95 in Miami,” she said. “The process is to find someone in the area to go meet with him.” But for that to work for Elmo, he would have to settle down, something he’s never been willing to do. He’s been too busy looking for people who haven’t heard his story.

“You want a story about Elmo Henderson?” says Joe Souza, a seventy-year-old cut man from San Antonio. “I’ll give you one. And it’s a true story. In 1972 Cassius Clay came to San Antonio. You know who that is? Yeah, Muhammad Ali. He came to do an exhibition against four Texas fighters, two rounds apiece. I remember it was Elmo going on first and Ronnie Wright going on second. And before the exhibition started, Ronnie says to Elmo, ‘Don’t agitate this man. I go on next, and I do not want to get the stuffing beat out of me.’ And so Elmo goes after Ali. It was just an exhibition, but Elmo goes after him. And he pissed Ali off, and Ali took it out on Ronnie. Ronnie raised hell about it afterwards. He said, ‘Elmo, you son of a bitch! Why did you rile him up?’”

To be exact, it was October 24, 1972, a time in Ali’s career that doesn’t get as much attention as the glory years that came before and after. His exile had ended, but he’d been defeated by Frazier. Working his way back up the rankings, he also fought frequent exhibitions to raise a little money for local charities and himself. Though far from being America’s sweetheart, he was no longer the bogeyman he’d previously been. Popular opinion on Vietnam had started to resemble his own, and as his career was discussed more and more in the past tense, sports fans began to show him some unfamiliar sympathy.

At the bouts he would clown around, exaggerating his trademark shuffle, hiding behind the ref, or going into a mock rage at someone sitting ringside. But he’d also show the fans what made him the Greatest. He’d throw flurries of punches so fast that many couldn’t be seen, stopping each punch just short of his opponent’s jaw. He’d put his hands behind his back and let guys pound at his body, dodging their head shots with jukes and feints. As lightly as he took the events, his opponents were serious. They knew that one solid punch could bring a knockdown and national attention or, if nothing else, something to tell their grandkids about. “There was never any script,” says Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee. “We always told them to do the best they could, and they did, because anybody that fought Ali would be known forever.”

The Muhammad Ali Boxing Show, as it was billed, rolled into San Antonio a few days before Tuesday night’s charity exhibition. Details of the event are hard to pin down; the coverage in the two San Antonio dailies, the San Antonio Light and the San Antonio Express, is somewhat contradictory and mostly concerned with the entertainment aspect of the event. According to the Light, the exhibition had been scheduled to feature Ali and three fighters, Ronnie Wright, Sonny Moore, and Terry Daniels, but Elmo had been added to the card after he had shown up for Ali’s pre-bout workout and popped off in the gym. Daniels, the biggest Texas draw in boxing at the time by virtue of his brutal loss to Frazier earlier that year, remembers Elmo monkeying with Ali at the prefight press conference. “Elmo went there and started fooling with Ali while Ali was talking,” he says. “So Ali started flicking jabs at Elmo to play around, and Elmo just calmly blocked them off, talking back to Ali, talking to reporters, guarding his face from those jabs. He never quit talking.”

But memories of the event are the province of aging men who, like Elmo, once made their living by being hit in the head. Daniels does not recall Elmo boxing Ali that night. Nor does Wright, who adds that while he can’t dispute Joe Souza’s recollection, he just doesn’t remember it himself.

The newspaper accounts, however, place Elmo squarely in the ring. The Express said that “Henderson danced better than Ali and made better faces . . . and he was chased after two rounds, undoubtedly by design.” The Light’s story offered only a little more detail: “The audience booed the lack of action in the first round . . . [But] Ali displayed his famous left jab and footwork in the second round, let his knees sag after a light blow to the jaw, then stalked a surprised [referee Charles] Golden as if he intended to work him over.”

None of it quite jibes with Elmo’s depiction. But neither is it so different as to rule out the version in his mind. It’s a line he’s been preaching as far back as Zaire, the story that defines him, not just for himself but for everyone he meets, and no one will ever persuade him he’s wrong. Ali’s own legend was built on a punch no one saw, at least not until slow-motion technology caught up with his talent, revealing that his second fight against Sonny Liston did in fact end with a crushing straight right that flew too fast for ringside eyes to follow. And for what it’s worth, Elmo once had a tape of his fight with Ali. He used to pull it out instead of his picture. Bill Nutto saw it, and he says it looked like Elmo tagged Ali hard. But Elmo says he left that tape on a bus in Reno a long time ago. Or maybe it was Oakland, and maybe last week. On that he’s not clear.

Whatever Elmo’s performance in San Antonio that night, it did set into motion the rest of his life, the sparring jobs with Daniels and Foreman, the holiday in Zaire, and his one real payday, in a courtroom in Corpus Christi. And it all began, as Elmo has always contended, with Ali.

Ali was looking for a jab, so I evened up on him and shot him a right. It was a good one. Even I saw lightning.

And that’s about it, sir.

I ran into Elmo one evening after work in September. I had just changed clothes and was on my way out of the building for a jog when I saw him sitting by the security desk. He had a new lid on, a navy-blue skipper’s hat with a SeaWorld logo on the front, and a new pair of bright white Nike basketball shoes. He said he just wanted to check in on me.

I told him I couldn’t hang around; I had to go do my roadwork, but it was fortunate for both of us that he had come by. The next day I was expecting a videotape compilation of old footage I’d found while researching his story, and I wanted to watch it with him. There was film that Leon Gast had sent that hadn’t made it into When We Were Kings. It showed Elmo dancing and shadowboxing in the ring with Foreman. There were scenes from another documentary showing Elmo chasing Ali out of the gym in Zaire where Foreman was working out, and leading an “Oh yeah” parade around the hotel pool. And there was a tape of a 1967-era Elmo fighting in Australia, long and lithe and, unfortunately, getting his clock cleaned.

Elmo’s face lit up. “Yeah, I remember that fight in Sydney,” he said. “The ref said he saw me get hit, and he called the fight. Here I am, I’m whipping this kid’s ass for eight rounds, and the ref gives him the fight. And you got a reel on that? Damn, I couldn’t get this lucky in Vegas.

“Well, anyway, you go on, get out the door, then work some more, and find out the score. I’ll be by tomorrow at a little after four.” And that was that. Elmo never showed up.

“Man, I’m a roadrunner,” he had told me one day at Mike’s Pub. “In life, like in boxing, you got to stick ’em and move. Keep sticking and keep moving.”

And then, inevitably: “That’s how I did Ali.”