Oh, man,” he said. Did I leave you with two dollars? I thought I’d bet it all. You better make a stand. Custer did, but of course you know that poor son of a bitch got massacred. So you can imagine what’s fixing to happen to you.”

Amarillo Slim was smiling when he said this, and I was laughing. We’d been playing his favorite poker game, no-limit Texas hold ’em, one-on-one, and the inevitable was coming to pass: After an hour and a half, he was winning my money. I was losing more or less happily, partly because the result had been so obviously foreordained and partly because Slim is such a funny guy. He is a hustler, a gambler, maybe the most famous gambler ever, and he makes losing money feel like a recreational activity. He’s done that for most of his life, as a pool player, bookmaker, and seemingly random bettor on just about anything. He has cut cards with presidents Johnson and Nixon and says he won $400,000 from Willie Nelson playing dominoes. He has outrun racehorses, sort of. Once he beat a table-tennis champ while playing with Coke bottles.

Mostly, though, Slim, known by his mother as Thomas Austin Preston, Jr., is famous for bringing poker out of the smoky back rooms and into the mainstream, where it thrives—in Las Vegas, online, and at regular Wednesday night games across the country. Slim did it with a combination of smarts, corn pone, and shameless attention-grabbing. He’s been called the Bobby Fischer of poker as well as the Imelda Marcos of the game, for his closetful of showy cowboy boots, most of which are stitched with his nickname. As he himself will tell you, he is “a dirty bastard.” Slim has made a lot of money over the past six decades hustling people, some of whom didn’t know better and many, like me, who should have. “If I’m gonna win,” he writes in his memoir, Amarillo Slim in a World Full of Fat People, due out this month from HarperCollins, “I sure as hell want to break somebody doing it.”

During our game, played at his 6,800-square-foot Amarillo home in March, he kept saying it was me he was going to break. But he kept telling me a lot of things. Talk is Slim’s weapon of choice—distracting his opponents with his deep drawl, getting into their heads, telling stories from a colorful life of hustles good and bad, bets made and lost. The stories usually end with some hilarious bon mot, obviously spoken many times over the years, such as, “He had as good a chance of beating me as getting a French kiss out of the Statue of Liberty.” These folksy one-liners may be part of Slim’s shtick, but they somehow always sound fresh, which makes them even more outrageous. Indeed, Slim just delights in saying outrageous things. “Tighter than a nun’s gadget,” he declared at one point. “I don’t know what it means,” he added, “but I just said it.”

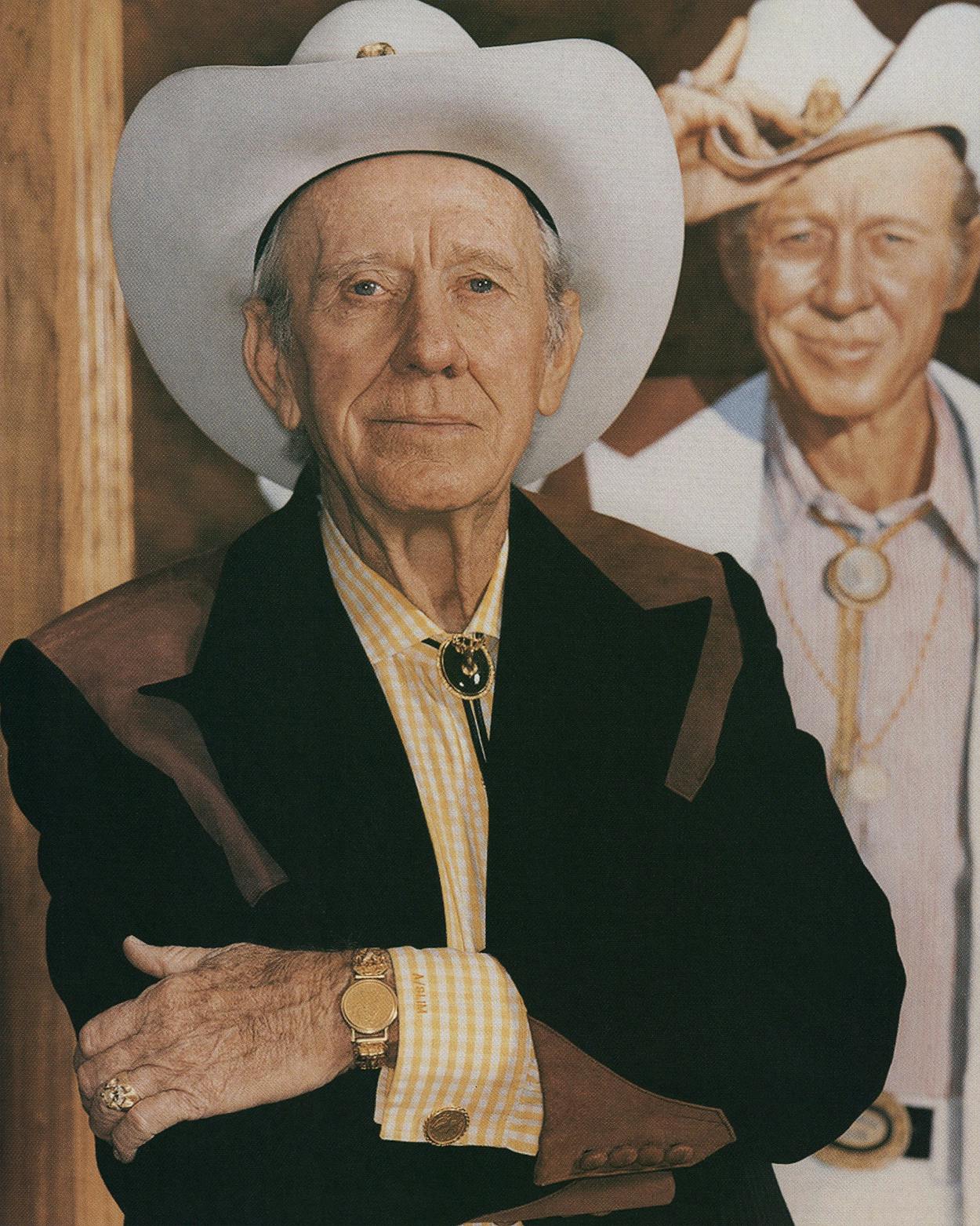

At six feet four and 170 pounds, Slim is defiantly slim. He’s 74, with longish, thinning hair, and looks like a character actor in an old western. Actually, he shares many features with Jimmy Stewart, especially the long, rubbery, perhaps deceptively kind face. Slim’s left eye is a little narrower than his right—maybe, I couldn’t help but think, from years of cagey winking. He wears a huge diamond ring on his left ring finger and a couple of gold bracelets. His belt, belt buckle, and shirt cuffs all bear his nickname. And he has soft hands, as you might expect of a man who has never held a job.

Texas hold ’em, the game we were playing, is the one that serious gamblers play. Nobody’s certain where it originated; some believe it came from Brenham, others think Corpus Christi. The rules are fairly straightforward: Each player gets two cards facedown, followed by a round of betting, then three communal cards are turned up at once (called the flop), then a fourth and a fifth are turned up. After each new deal comes another round of betting. Players use the five communal “up” cards and their own two “down” cards to make the best five-card poker hand available. What makes hold ’em so exciting is that attitude wins as much as cards; you can win with a terrible hand as long as you can bluff the other players. “Hold ’em has the most action and requires the most skill of all poker games,” Slim told me. “Any two cards can be a hand. Any two cards can beat any other two.” This is especially true when two people play “head up,” or one-on-one. The real action comes when both have good hands. In no-limit, either player can bet every chip he has and try to, as Slim says, break the other. (I asked what happened to stud poker, which used to be the game of choice. “Stud is like bumpers and fenders on cars,” said Slim. “It went out forty years ago.”)

Head-up no-limit Texas hold ’em isn’t only Slim’s favorite game; it’s his living. After years of seeking out people to hustle, now Slim waits for people to call him and try to con an old man. Recently, when he was in Vienna for a world head-up championship, he took some action on the side, traveling to Moscow, London, and Paris for another eleven games, at a minimum of $25,000 each. Of course, he won them all. I knew when I called that I stood about the same chance. The difference was, I had only $100 for my learning experience, fronted by my boss, with whom I regularly tussle at our weekly game.

So I went to Amarillo, where Slim lives with Helen, his wife of 53 years, works on one of his three cattle ranches, rides horses, hunts, and keeps tabs on the Preston family empire—four Pizza Planets, three Smoothie Kings, and two Swensen’s. We sat at a little table with green felt; on the walls were photos from Slim’s glorious past—shooting pool as a teenager, playing cards as a man, smiling with Muhammad Ali and Thomas Hearnes, playing dominoes with Willie, hanging out with Las Vegas royalty. How do you retire after such a life of glamour and risk? You don’t. You can’t. As Slim has found, there is always someone gunning for him. So he puts on his poker face and cuts the cards. “The thrill is there at the start,” he said. “I’m excited, the adrenaline is flowing. But after twenty minutes, I’m bored to death.”

Battling a writer for a big $100 couldn’t have helped matters. But at least for a while, I gave Slim a fight, winning ten of the first fifteen hands. I won when I could have, and I folded when I should have. Early on I gave up on two kings after Slim raised me $20. He could have been bluffing, but there were four cards to a straight on the board, and I had a feeling he had the fifth. “You did the right thing,” he said. “If you’d had another pair or three kings, I’d have broke your goat-smellin’ ass.” In other words, he’d have bet all his chips on his straight, and if I had had three kings—also a pretty good hand but not as good as a straight—I would have been tempted to put all my chips in too. And the game would have been over.

Slim is no stranger to breaking other gamblers. “I was a hustler,” he told me. “And I was a good, good one. I got a lot of scalps on the wall. The word ‘hustle’ does not offend me at all.” He was born in Johnson, Arkansas, in 1928, and his family moved to the Panhandle town of Turkey nine months later. They traveled around the state a lot, and after his parents divorced, the boy was shuttled back and forth between Arkansas and Amarillo. He was a cocky kid, good at math, who picked up snooker and began hustling pool in the Mexican part of Amarillo as a teenager. He got so skilled that when he joined the Army, shortly after World War II, he became an “entertainment specialist” who traveled around Europe, sometimes with Bob Hope, giving pool exhibitions. Slim, as he was known, spent much of his time running a black market in cigarettes and nylon hose and hustling other servicemen. In October 1948, he confesses in his memoir, he fixed a game at the GI World Series (he paid three players on one team to not hit the ball out of the infield) and won fourteen cars and a lot of money. “I still feel bad about it to this day,” he writes in his book. He returned home at age nineteen a rich man.

After marrying Helen Byler in 1949, Slim spent the fifties hustling pool. He, Helen, and their young son, Bunky, would travel the country, with Slim stopping long enough to make a little money in the local pool hall and then move on. Slim’s world was a lot like the one in the 1961 movie The Hustler, in which Paul Newman conned his way across fifties America, eventually going up against Jackie Gleason’s Minnesota Fats. Indeed, Slim battled the real-life Fats several times and learned some important things from him—the need to be brash and chatty and the need to sell oneself. It paid to have a memorable nickname, so he became Amarillo Slim. The name went well with his outfit—a Stetson hat and handmade boots. Slim played the bumpkin part to the hilt, making his hustle that much easier. “Everybody thought I was lighter than a June frost,” he said with a laugh.

Slim eventually gave up pool because everyone knew his reputation and the game required him to spend too much time on the road. He started bookmaking, and in the early sixties, he began seriously playing poker. He honed his craft in Texas, learning and mastering the new game called hold ’em, which Slim remembers playing for the first time in Brenham around 1963. When the first World Series of Poker was played, in Las Vegas in 1970, Slim was there with five other players and hold ’em was the game. Two years later, at age 43, Slim won and took home $80,000. In 1973 his first book was published, a how-to guide called Play Poker to Win, and he became a kind of pop star, a fixture in magazines and on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, where he playfully boasted and drawled well-worn lines like, “I’m the fourth-best player from Tulia, Texas.”

Slim played the bumpkin part to the hilt. “Everybody thought I was lighter than a June frost,” he said with a laugh.

During Slim’s pool-playing days, he had always been interested in what he calls proposition bets—wagering, say, that he could knock a couple of balls into the side pocket using a broom. But as he got famous, he began taking bets on any crazy thing. He challenged tennis pro and hustler Bobby Riggs to play Ping-Pong for $10,000, with Slim having the choice of paddles. He chose skillets. Of course, he had been practicing with them and handily beat Riggs. Seven or eight months later in Knoxville, Tennessee, a guy named Lefty, who had obviously heard about the Riggs hustle, challenged Slim to play a friend, who turned out to be a table-tennis champion. But Slim, after accepting and insisting on his choice of paddles, showed up on the day of the match without the skillets he knew the champ had been preparing with. His choice this time was empty Coke bottles, which he had been practicing with for a month. He won easily. Several times Slim bet he could beat a Thoroughbred racehorse in a one-hundred-yard dash—and then revealed that the course was fifty yards up and fifty back. By the time the jockey had the horse stopped and turned, Slim was nearly home. Once, he said he could drive a golf ball a mile and, after taking bets, led the suckers to a frozen lake and easily won their money. Slim is a smart man; he bets only on what he knows he can win. And for the past thirty years, people have taken him up on it. The key to proposition bets is understanding the nature of one’s fellow man, especially his greed and gullibility. To gamble may be human, but to hustle is divine.

Slim has a way of seeing your hand, even when he can’t see it. About halfway through our match, the flop showed a jack and two 3’s. Slim threw in his cards. “I ain’t got nothing,” he spat. “I can’t beat a queen high, and you had a queen, didn’t you?” Well, yeah, I said, but how did you know? “You didn’t have an ace or a king at the start, or you’d have raised, and you didn’t have a three or a jack going in, or you’d have raised. I guessed about a queen-ten.” Actually, it was a queen-9.

Slim calls this intuition; it might be called card sense. “I always know what I got,” he told me. “I’m always trying to figure out what you got.” He does this by doing the numbers and observing the players. Contrary to popular wisdom, poker isn’t so much about luck but about math and psychology—calculating odds and intentions, watching faces and listening to voices. In other words, says Slim, “poker is a people game.” The main way to figure people out is to watch their eyes (one reason Slim wears a hat). And talk to them. Slim plays poker the way Michael Jordan plays basketball—aggressively, talking trash the whole time, rattling his opponents, confusing them, manipulating them, trying to figure out what they have. In the biggest hand of our match, he chattered like a crazy uncle. I had a queen in my hand and there were three 3’s on the board, so I bet him $10.

“You must not have nothing,” he snorted. Then he asked, “Do you have a heart in your hand?”

I laughed—hearts were a nonissue. The trip treys were the only thing that mattered.

“Well, that’s not telling anything,” he cried. “Do you have a heart in your hand?”

I ignored him.

“Are either one of your cards a heart?”

I fought back feebly with my own brand of psy-war non sequitur. “Yes,” I said nervously, “this coffee is very good.”

He was unfazed. “Oh, you don’t have a heart in your hand. Okay. I call. I thought you had two 4’s. Now you might have made a club flush.”

Of course, neither fours nor clubs had anything to do with anything either. Slim had a great hand, a full house (so did I; we split the pot), and he was merely fostering chaos. “It’s just psychology,” Slim said about his nonstop banter. “I always graciously insult or put down my opponent. If they take it good, fine. But then I cover it up in a minute with either something complimentary or something distracting. If they don’t like it, then I overdo it. Because I really and truly don’t give a damn what people think, if the truth be known. Deal.”

Pop psychologists tell us that the reason gambling addicts always lose in the end isn’t just because they’re poor players; it is that deep down, they are self-loathing weaklings who want to lose. That may be so with some compulsive types, but it’s not true for those who make a living with figures and suckers. “It depends on what you think about yourself,” Slim said, explaining the difference between himself and the rest of us. “I like me. I like what I do. I’m a dirty bastard, but my word’s good.” For Slim, gambling isn’t an avocation; it’s his profession, one that has allowed him to enjoy the steady financial success of a big-city investment banker. He approaches poker the way speculators do the stock market, which he also plays: Don’t worry about short-term loss; look at the big picture, the long haul. Follow certain rules and procedures, bet certain hunches—you may lose on one hand, but you’ll win with the same hand the next two times.

Slim continues to play in all the big tournaments, though in some ways, modern poker seems to have passed guys like him by. In the old days, fewer than a dozen would play for the World Series title in Las Vegas, which still had its own small-town sleazy charm. Now Vegas is a huge entertainment complex, and poker is big business. Last year 631 players competed for the championship; thirteen former winners, including Slim, were bounced long before the final rounds. “These new guys learned to play from watching a computer or else from reading books,” he complained. “They play like robots.” Slim still makes big bets, though, and said that he and some “associates” won more than $500,000 betting on George W. Bush to win the presidency (“One of the first headlines I saw was the Denver Post, which said ‘Gore Wins Election.’ I couldn’t swallow boiled okra.”). And he’s become royalty in Las Vegas, getting inducted into several halls of fame, including the Horseshoe Casino Hall of Fame and the Legends of Nevada at the Tropicana Hotel and Casino. “My nomination and acceptance were by acclamation,” he said about the latter, noting proudly that other inductees include Howard Hughes and Benny Binion, two men who built Las Vegas.

These days, Slim mostly hunts, fishes, or hangs out on one of his ranches with his cattle or dozen prized racehorses, waiting for the phone to ring. “I’ve served my apprenticeship,” he said. “There’s nothing anymore I’m trying to prove. I’ve slowed way down. You get old, wore out, don’t have any drive or ambition. I’m at my best now when I’m on a horse and doing something. Everything I could do on a horse I can still do.” His famous nose for risk almost got him killed last Labor Day weekend when, riding a trail in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness area in northern Idaho, he fell off his horse, which then fell on him, breaking every one of his ribs. Slim was evacuated by helicopter and spent nine days in an intensive-care unit. “I’ve always heard you have nine lives,” he said, shaking his head at the memory. “I calculated mine up. I’ve already used up twelve.”

It was, of course, just a matter of time. I had about $30 in chips and two jacks—a pretty good hand. Slim raised, I re-raised, and he raised again. The last communal card gave him a pair of queens (or Siegfried and Roy, as Slim calls them), beating me and leaving me with $2. If I had been more aggressive in my initial betting, he would have folded with his queen high and I would have won the hand. That, says Slim, is why they call it gambling. My last stand lasted maybe another minute. “Ain’t that a bitch,” he crowed when it was over. “You done throwed the ball plumb over the fence, you’re a long way from home, don’t know anybody, and probably hungry.”

I thanked him for the lesson and he took my $100. It was all I could do not to pull another $20 out of my wallet.