This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

My ears are attuned to the voices of East Texas even though I’ve lived in the city for twenty years. “I oughta whup the tar outta you,” I hear a mother tell her son as I finger the Jacksonvile tomatoes at the farmers’ market. I linger around the okra, hungrier for the expressions of my childhood than for the produce.

In a doctor’s office a man from East Texas tells me about his heart surgery: “Last year I was sick to where I couldn’t hardly get out of bed.” He is clearly enjoying the attention that his failing heart has attracted from important city doctors. “I was brought up hard,” he explains.

The black woman shampooing my hair summarizes her sister’s life and recent death in one confident sentence: “She did what the Lord gave her to do.” I scribble the sentence in the margin of a magazine, tear off the scrap of paper, and put it in my purse.

Perhaps I am making up for the inattentiveness of childhood. With no other frame of reference, I, like most children, regarded the landscape of my childhood as ordinary. In 1956 my sixth-grade class celebrated the end of elementary school with a trip to Dallas, where we took in such extraordinary sights as Cinerama; the Health and Science Museum at Fair Park, with its shocking plaster representations of a baby being born; and finally Love Field airport, where I snapped a picture of Ed Sullivan rushing to his flight. That was the interesting world. Today I would bypass the celebrity and take more notice of my classmates, some of whom had had the tar whupped out of ’em, were being brought up hard, and might eventually do all that the Lord gave them to do.

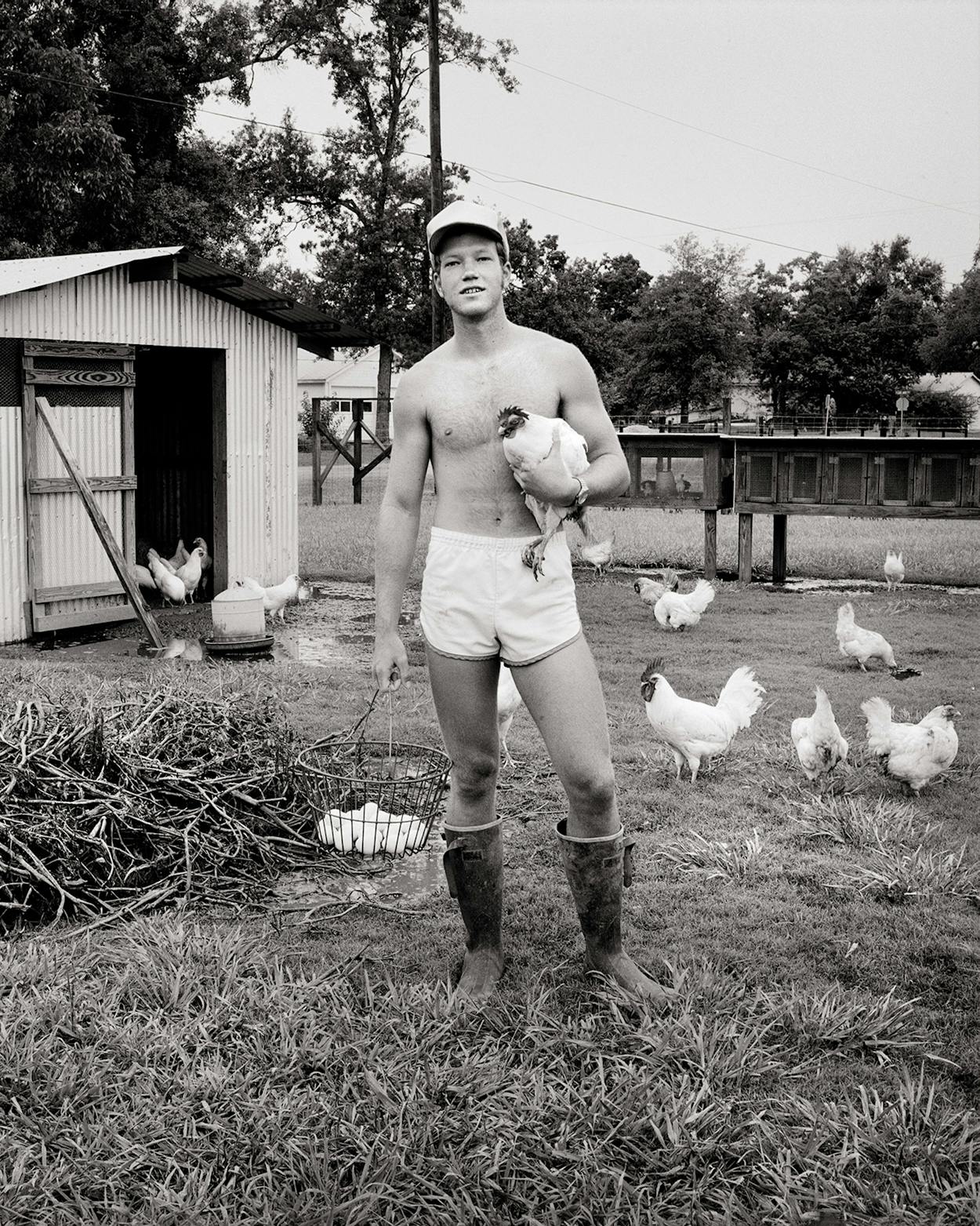

I was born two blocks inside the Texas state line in Texarkana. Keith Carter’s photographs of East Texas that appear on these pages were not taken near my hometown, nor were they taken 35 years ago, when I was a little girl beginning to sort out my surroundings. Yet these contemporary photographs, all taken between Lakes O’ The Pines and the Trinity River, conjure for me a rich overlay of memory—my own images of trees, family, pretentious dogs, religion, poverty, lapsed grandeur alongside enduring dignity.

Like all Texas schoolchildren, I spent the seventh grade studying Texas history and geography. I can sing “Texas, Our Texas,” and I once performed a modern-dance routine to “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” Sitting on the public-library steps, waiting for my mother to pick me up, I gradually memorized one side of the inscription on Jim Bowie’s statue: “Dreams of fabulous wealth brought Bowie to the San Saba region where he met with unexpected Indian attack . . .” I was even a delegate to Bluebonnet Girls State in 1961. My first writing effort appeared in the Texas Junior Historian magazine. Despite all those credentials, when I left the shadowy Piney Woods for the liquid blue skies and glaring limestone of Austin, I gradually realized much of what I had grown up believing was Texan was really Southern. The cherished myth of Texas had little to do with my part of the state. I knew dogwood, chinaberry, crape myrtle, and mimosa, but no bluebonnets or Indian paintbrush. Although the Four States Fair and Rodeo was held in my town, I never really learned to ride a horse. I never knew anyone who wore cowboy hats or boots as anything other than a costume. I knew farmers whose fences were bois d’arc and “bob wire” and whose property was known as Old Man So-and-so’s place, not ranchers with their cattle brands arched over entrance gates. I knew ponds, not tanks. Streets in my town were called Wood, Pine, Olive, and Boulevard, not Guadalupe and Lavaca. Mexico was so remote that we called it Old Mexico. I knew people and a lot of things in only two colors—black and white. In Austin I quickly discovered that women who had grown up with less shade and more sky seemed less constrained than I was by the Southern dictum “What will people think?”

It did not occur to me until I read William Humphrey’s 1964 novel, The Ordways, that my forebears in East Texas were the less adventurous of the Texas pioneers. Humphrey describes them this way: “Mountain men, woodsmen, swampers, hill farmers, they came out into the light, stood blinking at the flat and featureless immensity spread before them, where there were no logs to build cabins or churches, no rails for fences, none of the game whose ways they knew, and cowered back into the familiar shade of the forest, from there to farm the margins of the prairie like a timid bather testing the water with his toe.”

Cowering back into the familiar shade? Timid bathers? Could I still boast of being a fifth-generation Texan if my great-great-grandfather Samuel Corley had eschewed the vast and lonely Texas prairies to ride a Presbyterian circuit from San Augustine to the Red River? On the other hand, if the Corleys had charged on westward, their horses might have given out in Fort Stockton. I might have learned to sit a horse, but I would have missed the trees, the sandy-bottomed swimming holes, the hiding places, and the mystery indigenous to East Texas.

Historians have suggested that the trees in East Texas blocked our vision and walled us off from the outside world. From a child’s perspective, trees were simply an integral part of our games. How could a kid in Fort Stockton play a serious game of Tarzan or Swiss Family Robinson or even hide-and-seek without thick trunks, vines, and pine-needle carpeting? My mud pies were baked with mulberries or wild cherries. Chinaberries were ammunition. The partially exposed roots of an old oak tree could provide shelter for dolls or trolls or small plastic Indians. Magnolia trees offered totally enclosed play spaces, sturdy climbing limbs for even the smallest children, and cones with magic red-lacquered seeds.

Family provided additional shelter. Fifth cousins once or twice removed were counted as family. Family pride and the possibility of family shame were potent forces in East Texas. My father remembers being cautioned each time he left home, “Remember whose son you are.” Who you were counted for more than what you had, and according to my grandmother, what you never wanted to be was “common.” Texarkana was too big to harbor much of the clannishness or xenophobia that existed in smaller East Texas towns. A newcomer to those towns, even a much-needed doctor, might initially be welcomed with a flurry of Southern hospitality, but eventually the stranger would feel a chill while the locals withdrew to speculate on who his people were.

Families in East Texas were once bound not only by blood by also by certain traditions. My relatives could sing in four-part harmony, some could play musical instruments, and almost all could tell stories. Recently I had lunch with a handsome male cousin of mine who purports to be “ninety-two damn years old,” and right there in Wyatt’s Cafeteria I got him to recite “The Ladies” from Kipling’s Ballads and Barrack Room Ballads. Every time our family gathers, certain heartily embellished stories are told or at least alluded to. The stories of “The Rattling Fork,” “The Dog on the Tilt-Top Table,” “The Day Mama Ran Away,” “Uncle Burton and the Gideon Bibles,” and the adventures of Troubador, a well-known dog-about-town who urinated on the preacher’s leg during Chigger Corley’s funeral, cannot be written down. They are theatrical performances that require raucous audience participation and may require the tale-teller to assume the countenance of a dog. My family’s penchant for irreverent theatrical behavior was thought to be inherited and therefore unavoidable. Every time one of my brother’s tales caused my Aunt Lois’s legendary torrential cackle to erupt, he was rewarded by the family’s acknowledging, “Why, young J.Q.’s got a lot of his Uncle Burton in him.” Certain strains in families are tenacious. Uncle Burton, who has been dead 35 years, was surely smiling somewhere the night my own small son, who could hardly lisp his own name, returned from a Rangers game imitating the bleacher vendors’ “Co’beah? Co’beah?” I haven’t decided yet which of my three boys will have to memorize Kipling’s “Ladies.”

Trees sheltered us, and we were embraced by our families, but our churches taught us that all was lost if we weren’t “leaning on the Everlasting Arms.” Although my roots were Presbyterian and most of the family remained there, my particular branch of the family strayed first to Methodism and finally to the First Baptist Church, the biggest church in town.

Ours was such an all-encompassing, full-service church that even in the days before Baptist bowling alleys and gymnasiums, we felt sorry for anyone who was not a Baptist. I regularly logged six or seven hours on Sunday and at least three on Wednesday night. No church made more demands on its young people or accomplished such measurable results. I was personally convicted of my wormy sinfulness and need for salvation at the age of seven. Anybody who attended church regularly and remained unbaptized by the age of nine was just not susceptible to Baptist pestering. The total-immersion baptism, which followed a profession of faith before the entire congregation, was performed in a giant fish tank set in the wall above the choir stalls. Baptismal candidates and the pastor wore white robes. The somewhat terrifying gravity of my own symbolic death and resurrection to new life was lightened a little by my watching our preacher scramble into chest waders before performing the ceremony.

Once saved (always saved), we were lovingly goaded into memorizing vast amounts of the King James Bible. The Baptist Church taught us to listen, to speak, and to pray before large audiences, to sing and to read music. We had to learn to dance and play cards on our own. Instead of slacking off in the summertime, the church doubled its efforts with vacation Bible school and choir camps held at a Baptist encampment near Daingerfield. Church camp, with its prohibition against “mixed bathing,” only heightened our awareness of sex and caused some to seek more passionate togetherness as “prayer partners” in bucolic thatched tabernacles appointed for private meditation.

Some who were brought up in the East Texas Baptist tradition remember only its hypocrisy and the burden of guilt that came from being dangled over the pit of hell on a weekly basis. My memories are more affectionate. The Baptists offered a child the security of a personal and loving God, a sense of democracy (Baptists vote on everything), and the example of dedicated people who continued to care about you and probably pray for you even if you grew up to be an Episcopalian.

The evils of racial intolerance somehow never came up in Sunday school. I spent many a Sunday afternoon with the Baptist Girls’ Auxiliary, ministering to the children of gypsies who lived in the worst poverty I’ve never witnessed. The children smelled of urine and kerosene and lived in dark tar-paper lean-tos on the edge of town. There were more-stable, less-dangerous neighborhoods of black families living in similar conditions, but we never went there. Nevertheless, we naively prided ourselves on our close personal relationships with black people. I must have rocked a thousand miles next to Pinkie Satcher’s ample bosom. Almost everyone we knew in our neighborhood of small houses had some help with the ironing and the children, which allowed lingering elements of Southern gentility. Maids polished silver, dusted cut glass, and starched tablecloths and napkins in exchange for unconscionable wages, bags of worn-out clothes, and bacon drippings. I knew the maids in my friends’ houses as well as I knew their mothers. They seated us at the front of the bus and then matter-of-factly took their seats in the back. We regarded them with an odd respect. Their hard lives gave them mysterious capabilities and folk wisdom that we didn’t have. One of my older cousins credits his very existence to a black midwife who mixed a poultice of cobwebs and cow dung to stop the hemorrhaging from his umbilical cord. When I had babies of my own, I remembered their old wives’ tales: “Don’t hold your hands over your head. You’ll strange that unborn baby on his cord. Bite that baby’s fingernails off so he won’t thieve. Don’t let him look in the mirror. It’ll make him teethe hard. Cross broom straws in his hair to cure hiccups.” We did not think much about their lives apart from ours. I noticed the thick, puffy scars across Pinkie Satcher’s chest that my older brother told me were made by a razor, but they seemed so incongruous with the loving woman who sang me to sleep with “Fly Away to Jesus” that I could never bring myself to ask what had happened.

To see East Texas clearly, I had to get away from it. For two summers of my college years I worked in Washington, D.C., for Congressman Wright Patman, whose district covered eleven counties in northeast Texas. I read and clipped news items from small-town newspapers, and I composed congratulatory letters to grim-faced couples in the district celebrating their fiftieth and sixtieth wedding anniversaries. Eventually I also read and helped to answer stacks of mail that poured in daily. Reading those sad letters written with knife-sharpened pencil stubs in quivery script on cheap tablet paper addressed to “Dear Honorble” or “Dear Congress” or “Dear Mr. Rite” revealed a poverty and illiteracy I didn’t want to believe. “Somebody sed you cud hep me. I don’t see good and I can’t hardly work.” People wrote about their lost social security checks, their liver ailments, their no-account children, and their general despair that life could turn so bad. The last summer I worked there, 1967, I sometimes had to telephone grieving rural black women in towns like Tenaha or Bogata who had never been out of their counties and whose sons’ bodies were now being shipped home from places in the world they couldn’t imagine.

When I faced the level of need in my part of the state, the conservative politics that pervaded my high school civics class—the essay contests sponsored by the Daughters of the American Revolution on the threat of socialized medicine, and the communist plots seen in every welfare payment—seemed so blatantly hypocritical. Most of the people who petitioned Patman’s office could not take care of themselves. Too often, local political powers in East Texas—narrow-minded county commissioners, sheriffs, wealthy attorneys, or judges—lacked the vision or inclination to do anything more than exploit or maintain the status quo. If the federal government did not help those down-and-out people, it seemed to me they had nowhere else to turn.

If going away from East Texas allowed me to see its people with wider eyes, it also afforded a fresh look at the natural beauty that I took for granted as a child. Driving toward Texarkana in the fall or traveling toward Marshall through Longview, I now appreciate the reds and yellows and oranges of the dense trees that line the highway. My husband and sons’ interest in fishing gives me time and places to admire bluebirds, hummingbirds, wildflowers, persimmon trees, snaky vines, odd mushrooms, and butterflies that flit in and out of dappled shade. But any foray into the lush countryside of East Texas is also likely to turn up equal parts of devastation—the sandy-bottomed creeks despoiled by salt water from oil fields or trash dumping, once-green slopes stripped for lignite coal and left rusty and eroded, dense forests replaced with commercially profitable look-alike pines, and sweet-smelling air displaced by acrid odors of paper mills. Quaint small-town squares are boarded up, their merchants unable to compete with K marts and Wal-Marts on the interstates. Preservation and conservation are luxuries enjoyed by more-prosperous, better-educated parts of the country. East Texas, struggling to keep its population employed, has never thought it could afford them.

I have to rely a lot on memory when I return to East Texas. Several years ago while visiting my parents, I took my sons to see my first neighborhood school playground. A local kid doing handstands on the splintery seesaws challenged my boys, “Them ain’t hard. Y’all oughta try it.” As if it somehow compensated for their reluctance to stand on their heads, one of my sons said to me in a stage whisper, “He speaks bad English.” After their tour of my childhood haunts, which they found altogether unimpressive, they asked, “Mom, did you used to be a hick?” My urban children growing up in an affluent, almost monolithic Dallas neighborhood have temporarily pre-sorted the world by economic status, blue-jean label, educational attainment, and hairstyle into convenient categories—hicks, punks, airheads, and the rest of us. Without so much as a “Hidy, hy’re you?” I fear that they indiscriminately lump my hometown folks right in with the worst crackers portrayed in Mississippi Burning. They lack the memory to see the people or the places properly.

I cannot re-create for them the broader, intimate exposure to all sorts of plain and fancy people that small-town East Texas gave. I look at my oldest son’s school yearbook and compare it with my own. His class has a sameness about it—all clean, healthy-looking college-bound kids with overpriced clothes, all knowing little of the world’s pain, poverty, and eccentricity that I picked up just by osmosis. Leonard, who sat behind me in the second grade, had only one eye and sometimes delighted us by taking his glass one out at recess. Linda, across the aisle, sometimes had to see the school nurse about head sores. Some kids in our class were members of the Holy Roller church that didn’t allow women to cut their hair. I daydreamed a lot about how long their hair would get before we graduated. Johnny’s arm got broken when we were in the third grade, but his parents never had it set, so it always hung a little funny. Terry, who sat in front of me in the fourth grade, stepped on a rusty can, and because she had had no tetanus shot, she died of lockjaw. There was little fancy diagnostic testing then. Kids who now would be siphoned off into special education muddled right along with the rest of us. Through the years tough kids with names like Bubba or Butch, with lopsided ears, missing permanent teeth, uncorrected crossed eyes, kids who would never shed “hisself” as a pronoun or “he done it” as an accusation, became as much a part of the taken-for-granted landscape of my childhood as the young Dillard’s-department-store heir whose chauffeur drove us to country-club birthday parties. If in my college years I began to value philosophers more than plumbers, the balance was restored at my tenth high school reunion. I was eight months pregnant with my second child and could have been voted “most changed.” A former high school football hero, whom I had tutored in English grammar, asked me to dance. Assessing my prominent belly, I lumbered out of the folding chair, smiled, and said, “David, you’re awfully kind to ask, but you can’t be serious.” “Sure, I am,” he said. “I’m a butcher over at Safeway now, and I’m used to movin’ big slabs of meat around.”

My children giggle at the beauty-shop sign “Chic Le Doll” as we turn down a street we always called Boulevard. I never had my hair done there, but seeing the sign recalls hours spent in small front-room shops that we called beauty parlors. Getting a permanent was an all-day affair, and in the course of the day an attentive child could hear enough bizarre gossip to frighten her out of ever growing up at all. I remember puzzling for weeks over the conversation about “twisted ovaries” and how Juanelle “broke her water” right there on the kitchen floor before J.T. could get her to the hospital. I never found that soap operas could compete.

My boys see only the broken-out windows and transients lounging in the lobby of the old downtown Grim Hotel, but I remember meeting former president Harry Truman there and my father’s glamorous stories of dancing in the roof garden to Ted Weem’s orchestra. My children see a defunct boarded-up Union Station with pigeons roosting near a clock that stopped maybe twenty years ago. But I hear whistles and deep-voiced stationmasters calling “All aboard” for Nash, Leary, New Boston, De Kalb, Clarksville, and Paris, and somewhere in my memory is the statistic that 27 passenger trains once came through my town daily. I visit aging neighbors to whom I am still a little girl, and my boys squirm with boredom. My children can’t fathom how many people took a hand in my upbringing in a small town. There was no escape to anonymity.

East Texas has a mysterious hold on those of us who grew up there. In its flickering shade and light, it simultaneously revealed some truths and obscured others. We are left with paradoxes we cannot reconcile. How do I explain the love of language and a good story, the rural black speech rich with biblical “reaping and sowing and chastising,” and the relatives who once recited Tennyson, all coexisting with illiteracy and ambivalence about education? A music store in Dallas once ran a September special offering a shotgun with each piano purchase, an odd pairing of gentleness and violence that does not surprise an East Texan. In my childhood the genteel old lady in my neighborhood might be known for her wonderful heart and extreme generosity, but she could turn from hugging me and say to her black maid, “I thought I told you that I never wanted to see your black butt decorating this front porch.” Seeing gracious mansions bulldozed to make way for a hamburger stand, or a canopy of trees cut to widen a street near a dying downtown, leaves us with humbled notions about man’s wisdom. Is it any wonder that I still hum hymns when I do the dishes and that I was greatly relieved when a woman who heard me speak said, “Honey, I can just tell you’re anchored in the Lord.”

- More About:

- East Texas