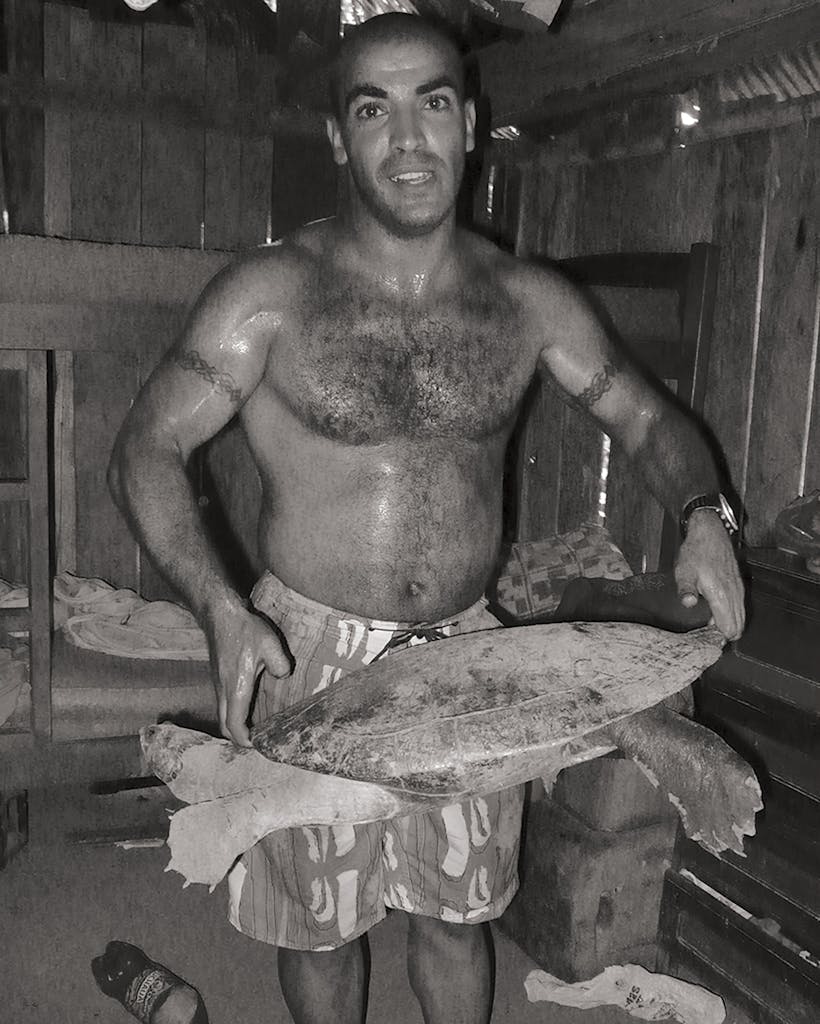

The first time Callie Quinn met Youssef Khater, she hated him. He was standing in the kitchen of their shared house in Santiago, Chile, carrying on about some extreme marathon in front of her other new roommates. While he smiled easily and was objectively handsome—a tightly coiled five feet six inches or so, with luminous brown eyes and boyish features—he also had tasteless tribal cuff tattoos on both biceps, seemed obsessed with expensive athletic gear, and was talking nonstop about the sponsors who were clamoring to support him as one of the best Palestinian runners in the world. She had just moved in, and already she found him insufferably arrogant.

A 23-year-old with blue-green eyes and alabaster skin, Callie had arrived in Chile just five weeks earlier. As a native of Canyon Lake, an hour outside Austin, she had longed to live abroad ever since taking a high school trip to the Galapagos Islands. Travel—specifically immersing herself in other cultures—electrified her, and when she enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin, she declared herself a geography major. In class, her professors repeatedly projected pictures of Chile and lectured on its sublime terrain. Callie vowed to live there after graduation. It didn’t matter that she didn’t know a soul in South America. (“I admired her courage and independence,” her father would later say. “At the same time, I wanted to wring her neck.”)

On March 4, 2011, she bid her parents and older brother farewell and boarded a flight for Santiago. Chile is the longest country on earth, with the driest desert, the Atacama, to the north and the volcanic daggers of Patagonia to the south, and Callie marveled at the landscape even from her airplane window. Santiago, the capital, sits nestled in a smoggy bowl between two mountain ranges; on the bus from the airport, Callie eyed concrete buildings and the chocolate-milk-colored Mapocho River. The city had a postapocalyptic patina, but it also had a strong economy, well-regarded English schools, and the second-lowest homicide rate of any major metropolis in the Americas.

Not that Callie was concerned about crime; first on her mind was a work visa. Chile, she’d heard, handed them out like candy, and she hoped to stay a year or two. Sure enough, it took only a month for her to earn an English-language teaching certificate and snag a job at Bridge Linguatec Institute. There she learned of an opening in a twelve-bedroom, hostel-like house on Avenida Condell, a tightly partitioned two-story in the leafy neighborhood of Providencia that was painted in almost as many colors as it slept nationalities. Loud and mouthy, Callie easily befriended several of her roommates. She accompanied Edmund Attrill, a leonine Brit who had studied theater, to protest the impending construction of a hydroelectric plant in Patagonia; she went out dancing with Sabine Schmidt, a stern German with a gap between her teeth who once got upset at a study showing Germany to be the least funny nation; and she told goofy jokes over pisco sours with Molly Parsons, an English teacher from San Antonio whose eyes fluttered upward when she spoke. Bonding over their Texas roots, the two soon became best friends.

And then there was Youssef, who complained that she talked too much. At 33, he was older than the others. He had been born to Palestinian parents in Haifa but grew up in Denmark, and now the Federación Palestina de Chile—an organization representing the country’s sizable Palestinian population, the largest outside the Middle East—was sponsoring him in his quest to set a record by running the 2,653-mile length of Chile. Over dinner after his long hours of training, Youssef would regale the roommates with accounts of his time in the Danish special forces—how he’d had to stand for minutes in a room full of mace or swim to the bottom of forty-foot-deep pools. Ed and Sabi, who were especially close to him, hung on his every word. Callie just rolled her eyes.

But after several weeks in the house, she had to admit that he did have a certain magnetism, and that his heart was nearly as big as his tales. If a roommate caught a cold, he’d run out to the grocery store for kiwis and limes, to make what he called a “vitamin C smoothie.” He gave away the extra Under Armour sports clothing he received from his sponsors and administered acupuncture, which he’d learned in Denmark, in the living room for free. One rainy afternoon, he decreed it “chocolate day” and, after ransacking the grocery store for sweets to share, gathered the roommates for a showing of Cool Runnings, his favorite movie. When he began dating a fellow Palestinian, a stunning dance teacher and single mother of two named Sohad Alamo, he hosted a barbecue birthday party for her nine-year-old daughter. Callie began to take his stories in stride. Once, when she was Skyping with her mom, he poked his beanied head into the frame. “Now I see where Callie gets her good looks,” he said, smiling.

So in July, when Youssef mentioned that he’d just purchased two new condos downtown and offered to rent one to her and Molly, Callie didn’t think twice. It was winter in the Southern Hemisphere, and their house had no heat—it was 36 degrees outside and in. The condos were not only heated but at the center of the city’s nightlife. She and Molly gave Youssef a security deposit and their first month’s rent, about $1,000 between them. On Wednesday, July 20, the day before move-in, Callie arranged to meet Youssef at eight in the evening on a street corner downtown so he could show her where to pick up the keys the following morning.

Youssef arrived thirty minutes late. He was in high spirits; three Danish women had been kidnapped in the Atacama, he said, and he was meeting up with some of his old buddies from the Danish special forces later that evening to make plans to rescue them. But first, he announced, he would take Callie out to celebrate her new digs. After an almost hour-long, meandering journey to the real estate office—Youssef didn’t seem to know where he was going, and when they finally reached the office, Callie noted that it was surprisingly dingy—they agreed to walk the mile or so back to Providencia, where they would eat. It was the first time Callie had hung out with Youssef one-on-one. As they ribbed each other, she found that she was actually enjoying his company.

A little past the river, Youssef’s cell rang. It was Sabi, and Callie could discern from the sharp tones that she was upset. Youssef, it turned out, owed Sabi money; over the past few months, he had borrowed from her and two Mexican students who had recently moved out of the house. He had not yet repaid them, and the three now needed the money back: the Mexicans were leaving for Buenos Aires the next morning, and Sabi was leaving for Ecuador shortly thereafter. Youssef assured her that he had the cash—in fact, he was carrying it in his backpack. He would not be home until late, but he would send the backpack home with Callie.

It was nearly eleven o’clock when Callie and Youssef finally sat down for dinner at Entre-Choke, a bar a few blocks from their house. Youssef ordered lomo a lo pobre and vodka drinks for the two of them. She had never seen Youssef touch alcohol; in fact, he always declined the Carménère shared around the house. Yet here he was, downing three consecutive screwdrivers. The Chilean national soccer team was playing on a TV in the corner, and Callie was amused watching Youssef grow animated, talking faster and faster, saying how happy he was to help her and Molly. Did she remember, Youssef asked at one point, that house he’d pointed out on their walk, the one that had burned down a week ago? Callie nodded, noticing his long, upturned eyelashes. He’d heard there was a golden toilet seat inside. He grinned.

Callie’s phone rang. It was Sabi, calling to ask why she wasn’t home yet. Callie explained that she was at dinner but, per Youssef’s request, didn’t say with whom. Fifteen minutes later, Sabi called again. Callie promised to be home soon. When Sabi called a third time, Youssef told Callie to ignore the phone. “She’s obsessed with me,” he said. He changed the subject back to the golden toilet seat. They should go find it, he said, looking into her eyes and smiling again, a little flush. Callie laughed. It was ridiculous, but she was game.

The house was actually one of Santiago’s oldest tire shops, Vulcanización Escoda, and after the fire, the facade had been covered up with corrugated metal. When they reached it, Youssef parted the rusted sheets, and he and Callie slipped in. The ceiling had burned away completely, leaving a portal onto the fuzzy midnight sky. Ashes fluttered from every surface like millions of moth wings. Youssef, after looking around for a tool with which to pry the toilet seat off, rustled up a crowbar. He led the way to find the bathroom.

“That’s not gold,” groaned Callie as soon as they edged into the lavatory. The toilet seat was generic beige plastic. Institutional eggshell.

Youssef decided to pry it off anyway, working the crowbar around the back edge.

“I’ve got to go,” said Callie. “I have work at seven-thirty.”

Youssef told her to wait; he didn’t want the soccer fans who were now spilling out onto the streets to give her trouble. Callie, unconcerned, made her way back toward the entrance. She didn’t hear the footsteps in the ash behind her.

“Hey, Callie—” called Youssef, and as she began to turn, she felt the crack of metal across the back of her skull. She fell backward. A knee shunted into her ribs and pinned her to the cold concrete. When she opened her eyes, Callie saw Youssef’s face, contorted with rage, inches away from her own. He was straddling her now, his hands grabbing her neck.

“Why did you tell Sabi that I owed you money?!” he spat, his fingers wringing her windpipe tighter and tighter, his brown eyes fixed on her with an unflinching intensity. “Why!”

Callie couldn’t comprehend. “You’re going to kill—” she choked, before the hot ringing pain, the anger, and the ash overtook her. Then she saw nothing at all.

It was past midnight, and Sabi tossed and turned. She’d been trying for weeks to get Youssef to pay her back, only to get excuses: he couldn’t give her the money because his passport had been stolen, or because he’d left the cash at his girlfriend’s house, or because the bank hadn’t processed his request. Just the day before, she had arranged to meet him on a street corner downtown, but when he hadn’t shown after fifteen minutes, she had angrily left to prove a point. He’d borrowed close to $1,000 from her and roughly $550 from the Mexican students. That he was taking advantage of their friendship was inexcusable.

Sabi called Callie’s phone again, but it was off. She dialed Youssef, and when she got his voicemail, she rang again, and then again. Finally, at one in the morning, he answered. He was on his way home. He’d given the money to Callie, he said, and they’d parted long ago. Had she not made it back?

Before long, Sabi heard Youssef downstairs. He was knocking on Ed’s door, and then Molly’s, asking if they’d seen Callie; when Sabi headed out to the landing, the three were discussing her whereabouts. Sabi eyed Youssef. It was freezing outside, yet he seemed to be sweating. His hands were shaking. “Where’s your coat?” she demanded. Youssef replied that he’d been running—literally running—between bars with his buddies. Then he launched into a barrage of questions. Who else did Callie hang out with? What if she’d been attacked for the money? Should he go search for her? “You were the last one with her,” snapped Sabi, heading back to her room. “It’s your fault if something happens to her.”

Youssef appeared distraught, and over the next hour, Ed and Molly brainstormed with him in the living room about what to do. Then, gazing out the window, Ed froze. Beneath the orange glow of the street lamp, a disheveled figure with a shock of tangled hair was stumbling along the sidewalk, gripping the house’s iron fence for balance. Ed recognized the long puffy coat. “Look!” he gasped. “Is that Callie?”

He and Youssef ran out to the front gate, Youssef leading the way. When they reached Callie, she was so dirty, so slicked in a black silt, that it took a second to confirm that it really was her. “Oh, my God! Are you okay?” asked Youssef.

Callie trembled. “How could you do this to me?” she yelled. “How could you do this to me?” Ed, confused, stepped back. Youssef moved to brace her by the shoulder. “Get away from me!” Callie screamed, careering past him and stumbling into the house, where she collapsed into Molly’s arms.

Sabi, hearing the shouts from her bedroom, hastened downstairs. Callie was filthy, her blackened hands leaving streaks on the walls as she tried to steady herself. She could not stop coughing. Sabi stared. She wondered what Callie could be covered in—was it paint? Pigment?—but all Callie could talk about was taking a shower. Sabi and Molly helped her into the bathroom and wrangled her out of her soiled clothes. As Molly worked shampoo into Callie’s fine hair, she caught sight of a gash on her head, a deep wound gnarled with matted hair and coagulated blood. Fearing Callie’s skull was cracked, Molly panicked. Sabi immediately hailed a cab, and they bundled Callie, her face still dirty, into the car to take her to the hospital. Callie’s eyes were now swollen shut, the size of walnuts. She began to vomit blood.

Youssef, meanwhile, had been pacing the kitchen. “I didn’t do anything,” he protested, wide-eyed, before the women left the house. “How can you say this?” Ed pulled Youssef aside and tried to comfort him. Perhaps Callie had had too much to drink, he offered. When Sabi called from the emergency room to say that the hospital needed Callie’s identification, Ed scrambled to find her passport and deliver it. He told Youssef to stay behind and relax.

Callie vomited blood again, and as she was finally wheeled into a hospital room, Molly struggled to keep pace with her friend. In snatches, Callie explained that she’d been struck and strangled. Only a dream had brought her back.

In the dream—one that lasted ten sticky, stretchy minutes, or maybe it was only seconds—she was bound in blackness. She could hear her mom and her dad and her brother furiously screaming around her. Molly had been there too, screaming with them. Wake up, Callie. You have to wake up! “I’m trying!” she’d screamed back. “I can’t get out!” Her arms and legs wouldn’t move. She was constricted.

And then the tight, velvety black of her dream had given way to the cold, grainy black of canvas. She’d been wrapped in a tarp—its seam, by some stroke of luck, facing upward. As she wrestled it open, ash had crashed into her eyes. She’d sat up, coughing, covered in soot and cinders, and discovered that she had been dragged into a dank closet. She had been buried alive beneath nearly a foot of ash.

Youssef was dangerous, Callie stressed, and though Molly believed her—and the doctor determined that her head injury had not affected her recall—Ed and Sabi were skeptical. When Molly relayed the story to them in the ER waiting room, the two exchanged glances. It wasn’t possible. Callie had to be confused.

Ed and Sabi returned to the house, where they found Youssef awake on the sofa, looking tense. He winced in sympathy as they told him about Callie’s temporary vision loss, due to eye lacerations from the ash, and nodded anxiously as they wondered whether she might have been raped by her attacker. But he was most agitated by Callie’s accusations, insisting he was innocent.

Staring at the violent streaks of ash down the hall, Sabi began to cry. “Who would do something like this?” she asked. At 5 a.m., the three decided to turn in.

Half an hour later, unable to fall asleep, Sabi heard the stairs creak, then a knock on her door. It was Youssef. He looked devastated. “My mother is dead,” he told her. “I’ve got to fly to Denmark.”

Sabi stared, jangly with exhaustion and now fright. “Okay,” she said. A couple of hours later, Ed helped Youssef load his bags into a cab.

Callie was certain that Youssef had tried to kill her. But why? As she lay in the hospital the next day, hacking up ash and unable to see, Molly filed a police report. When an olive-uniformed carabinero came to take a statement, Callie found she couldn’t explain the attack. Youssef’s words as he strangled her had made no sense, and she couldn’t fathom why he’d get violent over so little money. The officer, though polite, seemed perplexed. If she’d been strangled, why were there no bruises on her neck? His report dismissed the incident as a domestic dispute between two foreigners.

That afternoon, Molly tried to reach Callie’s family in Texas, eventually locating her brother, John Brian, on Facebook. “I’m at work,” he typed from San Antonio. “Please explain as best you can how serious this is.” Callie had been attacked, wrote Molly. She’d suffered a concussion, corneal abrasions, and a lesion in her larynx and received nine stitches in her head.

4:43 p.m. / John Brian: was she raped?

4:45 p.m. / Molly: no

4:45 p.m. / John Brian: are you sure

4:45 p.m. / Molly: she is almost positive i think women can tell most of the time

4:48 p.m. / John Brian: tell [her] I love her

4:48 p.m. / Molly: she loves you too

4:48 p.m. / John Brian: i want to kill who did this

4:48 p.m. / Molly: she’s right here and awake he’s ex secret service for the royal danish army pretty difficult guy to kill

4:49 p.m. / John Brian: are the police after him

4:49 p.m. / Molly: well . . . i filed the report but this is chile and it’s a conflict between two foreigners

4:50 p.m. / Molly: if he left the country already there’s not much they can do

When Callie’s parents, Jeff and Elaine, got the news, they were in San Antonio, buying supplies for a Quinn family reunion in Canyon Lake. They rushed home and logged on to Skype; when Elaine saw her strong-willed daughter’s crusted eyes, partially shaved scalp, and swollen stitches, she began to sob. Callie forbade them to come to Chile—she didn’t want to worry about them with Youssef on the loose. Then she uttered words neither parent had ever heard her say: “I want to come home.”

Sabi, trading shifts at Callie’s bedside with Molly and Ed, replayed the night’s events in her head. Listening to Callie describe the incident to the police, she’d realized with horror that it was the sort of account that was impossible to make up. She decided to message Youssef’s girlfriend on Facebook, hoping to learn whether he’d made it to his hometown of Brønderslev, a six-hour drive north of Copenhagen, or if he was still in transit. When Sohad finally called on Friday morning, Sabi couldn’t contain herself. “Where’s Youssef?” she asked. The reply left her cold.

“He’s with me,” said Sohad. Youssef had arrived at her house around nine-thirty on Thursday morning with three pieces of luggage. He’d said he was on the way to the airport for his mother’s funeral in Denmark, but he couldn’t leave without saying goodbye. The detour, however, had cost him his flight, and he had spent the rest of the day with Sohad. She was currently at work, she said, but as far as she knew, Youssef was still at her house.

Sabi tried to explain what had happened to Callie, saying she would send the police. Sohad listened in silence. When she went home a couple of hours later, she ate lunch with Youssef, wondering if the warmhearted man before her could be capable of such an attack. Sabi alerted the carabineros, but they never arrived. Around seven, Sohad left to pick up her two children and returned to find a handwritten note. He’d found a flight, Youssef wrote, and he loved her and was grateful. Later that night, he posted on Facebook: “Very hard to lose my mother and the love of my life on the same day.”

But he had left his three suitcases behind.

Three days after arriving in the hospital, Callie was discharged. She holed up in a spare bedroom at her boss’s apartment, eating soup and smoothies while she waited for doctors to clear her to fly back to Texas. Spooked, her roommates also began making plans to flee Santiago: Sabi to Germany, Molly to the U.S., and Ed to England. Ed, whom Youssef had invited to share his other condo, detailed Callie’s attack on Facebook. “So yeah,” he wrote, “basically this bastard is still at large, as the Chilean police are being useless. The whole saga has left us all shaken up, and I just feel like I need to get out of here. . . . Love and limes.”

His message got forwarded to the one person in Santiago who friends thought might be able to help: Rocío Berríos. A 33-year-old lawyer with cat-eye Prada glasses and a mane of black hair that she always treated as if it were an imposition, Berríos was a criminal attorney who loved taking on Chile’s most lurid cases. A former journalist, she had enrolled in law school after obsessively following a high-profile innocence case in which the police had wrongfully accused eight men of murder. When a classmate’s father became embroiled in one of Chile’s biggest government corruption scandals, Berríos proved to be so good at poking holes in the prosecution that she’d replaced the lead defense attorney.

Berríos remembered Callie—the two had met briefly at a party after the power-plant protest—and decided to pay her a visit. Warm and friendly, with a penchant for quoting lines from Seinfeld and punctuating every sentence with a throaty laugh, Berríos was engrossed by Callie’s account. Knowing how difficult it could be to navigate Chile’s judicial system, she offered to represent Callie pro bono and help put Youssef behind bars. (In Chile, victims with means frequently hire a private attorney to represent them in criminal cases, which often involves working with the overburdened prosecutors.) Callie agreed, and Berríos immediately alerted the homicide unit of the Policía de Investigaciones de Chile (PDI) that a would-be murderer was on the loose. She interviewed the waitress who had served Youssef and Callie dinner—the nineteen-year-old corroborated Callie’s memories of the evening—and coaxed Callie, Sabi, Molly, Ed, and the Mexican students to give sworn statements to the PDI, to persuade a judge that there was probable cause for Youssef’s arrest. The warrant was granted in short order.

But where was Youssef? Late one night, sitting at the Lucite desk in her loft apartment, Berríos stumbled upon an article online about how Youssef Khater had organized a 24-hour race outside Copenhagen in 2009. Searching further, she discovered that he’d won first place in the 100-kilometer Jungle Marathon in Brazil in October 2010, as a runner representing Palestine. The following January, the Federación Palestina de Chile in Santiago had heralded his arrival to the country on its website, announcing his intention to run the Atacama Crossing ultramarathon on March 6, 2011, and asking community members to contribute to his running fund. Scrolling down the page, Berríos noticed an odd comment. Youssef was not a marathoner but a scammer, someone had written in Spanish. Berríos clicked to reply. “I am looking for information on Youssef,” she wrote. “How can I contact you?”

The next day, as she waited for a response, Berríos reached out to a friend at Las Últimas Noticias, one of Santiago’s most-read tabloid papers. She needed to harness the power of the public. On July 29 the paper printed a front-page story about Callie, including a close-up photo of her green irises sunk in a hammock of red vessels, framed by watery lashes. The story was picked up by Chilevisión, a TV news channel, which blasted out photographs of Youssef and aired interviews with Callie and the custodian of her former residence, who had discovered Callie’s ashy clothes on the back porch.

At 1:53 a.m., mere hours after the tabloid story went online, Berríos received a Facebook message.

Hola Rocío:

I just saw the LUN article about Youssef Khater, and you have all my support to help. . . . Let’s make a plan to get you the info you need, and to put you in touch with others affected.

Regards, Carlos

Carlos Medina was a member of the Federación Palestina. He had seen her query on the website. His Facebook page, Berríos noted, was practically an homage to Chile’s Palestinian soccer team; in his profile picture, Medina posed in front of an Egyptian pyramid, his wavy, peppered hair parted down the middle, sphinxlike. He was a computer engineer. He suggested they meet the following day during a happy hour with his co-workers.

What Berríos learned, over the course of several hours and pisco sours, would undo everything she knew about Youssef. Medina explained how he and his friend Carlos Krauss had helped raise about $8,000 to sponsor Youssef in the Atacama race; to their knowledge, a Palestinian had never won an extreme marathon before, and they were excited to show the world that Palestinians weren’t just a bunch of terrorists. But from the start, they’d noticed some oddities. First, Youssef arrived with a friend in tow, an affable, blond British marathoner named Dominic Rayner, whom he had apparently led to believe would also receive sponsorship. (The Palestinians had never heard of Rayner.) Though Rayner paid for his own lodging and meals, Youssef bad-mouthed his friend constantly for being a freeloader, ditching him at every opportunity. (“What kind of friendship is this?” Krauss had wondered.) Then, on the second day of the race, Youssef dropped out, saying that the organizers, claiming that they’d noticed a muscle tear in his leg, had forced him off the course. He suspected that the move was racially motivated.

Crushed and incensed, Krauss and Medina insisted he get it examined to prove wrongdoing. Shortly thereafter Youssef quit returning their texts and phone calls. By the time the diagnosis came in—no muscle tear—Youssef had vanished. Perplexed, Krauss contacted Rayner, who had gone back to London. As far as he knew, Rayner told the Palestinians, Youssef was still in Santiago. Then came a twist: Youssef, he said, owed him money. Not only had Rayner bought him $12,000 worth of Under Armour gear, he’d also given him about $38,000 to buy some properties in Brazil that Youssef had suggested going in on together. (The real estate lawyer supposedly brokering the transaction kept supplying excuses—in strangely worded, typo-ridden emails—for why he couldn’t send Rayner a receipt, then accidentally signed one “Youssef.”) When Rayner demanded his money back, Youssef offered two options: he could send a wire with the sum or Rayner could fly back to Santiago and collect it from the lawyer in person.

Krauss and Medina urged Rayner to return. It was the only chance he had of seeing his money, and they were all eager to learn where Youssef was hiding. Rayner, though wary, agreed, hoping to bring him to justice. He contacted Youssef, who promised to meet him at the airport. When the Brit landed, at seven-thirty in the morning on April 1, Youssef was nowhere to be seen. He finally met Rayner in the city more than twelve hours later, gaunt and on edge. He led Rayner on an hour-long walk to show him where he was living, on Avenida Condell—in the very house Callie would move into two weeks later—then insisted on spending the night in Rayner’s hotel room. Youssef explained that the lawyer’s office was just half an hour away, and he didn’t want anything to impede their meeting the next morning. Rayner, alarmed, acquiesced only because he knew if he didn’t he’d never see Youssef again.

Rayner would never see his money. The following day, half an hour turned into three as Youssef led him on a circuitous path around Santiago and eventually to the outskirts, where they hiked to a ritzy hilltop suburb where Youssef said the lawyer worked. The hike was so steep that Youssef picked up a walking stick; when Rayner suggested calling a cab at one point, Youssef insisted they were five minutes away. Then, after dropping behind to tie his shoe, Youssef suddenly charged Rayner, swinging his stick savagely at the Brit’s head. The blow missed by mere inches. Startled, Rayner rushed headlong into Youssef, yelling; as the two men tumbled into each other, Rayner cracked his head against a rock. Youssef scrambled for his stick, raised it above his head, and, just when he was about to deal Rayner a decisive blow, halted—he’d noticed two curious bystanders.

Trembling and manic, Youssef instead wrestled Rayner into a ditch, begging him not to tell anyone what had happened. He had spent Rayner’s money, he said. He then refused to leave Rayner’s side, following as the Brit caught a bus back into the city. As the two sat in silence, bruised and bloodied, Youssef scribbled out an IOU for $55,000.

Terrified, Rayner left Santiago the next day, reporting Youssef to authorities—the British Metropolitan Police Service and Interpol—only after arriving in London. Feeling paranoid that he’d been a victim of a terrorist plot (had Krauss and Medina set him up?), it took him a full week to reply to the Palestinians’ emails and file a report with the Chilean consulate. Now, Medina told Berríos, none of them knew Youssef’s whereabouts.

Listening, Berríos was buoyed by one detail: if Youssef had remained in Santiago after attacking Rayner, he’d probably also stayed after attacking Callie. She met with the lead PDI investigator, Nelson Contreras, and the pair began reaching out to new contacts supplied by Rayner, Krauss, and Medina. It seemed that every place Youssef went, money had disappeared: during the Jungle Marathon, he’d stolen cash out of a friend’s bag and framed a hostel owner; he’d also persuaded a Norwegian runner to withdraw nearly $10,000 to invest in Brazilian property, then grabbed the bills from the car and sprinted off. In Copenhagen, he had placed a newspaper ad offering a free stay at a “sports city” built by a prince in Dubai to any athlete who could pay his or her own way; he’d then persuaded nearly fifty people to transfer him money—more than $28,000 in all—so he could purchase their flights. The day before the money was due to the airline, his apartment had mysteriously caught fire, supposedly preventing him from buying the tickets or returning the money.

Exhilarated by her discoveries, Berríos was hardly sleeping. Youssef’s cons in Denmark had been covered extensively in the newspaper Hvidovre Avis; though he was identified only as “YK” and his face was blurred out, in accordance with Danish law, his atomic-ant body and tribal tattoos were unmistakable. He’d been arrested in Denmark in the fall of 2009 for several schemes, including the Dubai venture, but he’d failed to appear for his trial in January 2011. He was still wanted for arson, embezzlement, forgery, and fraud.

As Berríos continued to dig, a Palestinian activist and Danish citizen named Maher Khatib decided to do some sleuthing of his own. A photographer who had initially introduced Youssef to Medina and Krauss, he was furious at Youssef for besmirching the reputation of the Palestinian people. After hours of trying to track down Youssef’s family, he discovered a sister, who was a lawyer in Copenhagen. According to Maher, when he got her on the phone, she burst into tears. “He has destroyed our lives,” she sobbed. “He has always been like this. My mother, brother, and I don’t have any contact with him.” Then she revealed another detail. Youssef wasn’t originally from Haifa, as he’d claimed. He’d been born in Beirut before the family emigrated. They weren’t Palestinian at all—they were Lebanese.

Berríos shared every bit of news with Callie. Youssef had wheedled his way into the Palestinian community and taken advantage of their national pride for money, she explained. He was only an average runner, and he had served ten years with the Danish marines before being dishonorably discharged for fraud at age 28; it seemed unlikely he had served with the special forces. As for the new condos? Those were a scam too. Callie’s mind reeled. Had Youssef’s stories, his generosity, his hours of training really all been an act? She took comfort in the fact that at least she wasn’t the only one to have fallen for his schemes. When she finally boarded a plane back to Texas, on August 3, Berríos promised to stay in touch. Youssef was motivated by money, she told Callie, and money would be the way to bait him.

In fact, over email, Berríos, Rayner, and Youssef’s Norwegian victim soon figured out the perfect plan. Youssef, they discovered, had just written an ex-girlfriend asking for money for an arm and leg amputation. If she wired it, the PDI could nab him at the pick-up counter. The ex refused. But then, a few days later, another woman agreed to wire him $120. Berríos made plans to have the PDI surveil the city’s transfer counters, looking for Youssef.

The night before the wire was to take place, however, Berríos learned that Youssef had written the woman to say that he was sending a Taiwanese sponsor of his named Lin Chia-Min to pick up the cash instead. “We’re f—ed!” Berríos told Contreras. Now they wouldn’t know whom to look for, or whether he would lead them back to Youssef. But within a few hours, Contreras had tracked down an address for Chia-Min—who turned out to be a 23-year-old textile worker for a company designing a sportswear line—and dispatched PDI officers to stake out his house.

The next day, at around three in the afternoon, officers followed Chia-Min to a Chilexpress money agency. There, waiting for him on the sidewalk, was Youssef. Leaping from their car, the officers arrested Youssef on the spot. (Chia-Min, who was clearly confused by the event, was let go.)

On August 9, two days before she turned 24, Callie received an email from Berríos. “We got him. Happy birthday!”

In the hours after his arrest, Youssef congenially led the PDI officers to the Hotel Lyon, a quaint establishment with antique sconces and parquet floors just a mile and a half from the house he’d shared with Callie. He’d spent the past two weeks there. He allowed investigators to take any evidence they wanted; when the hotel concierge asked what was going on, she was shocked by the answer. Youssef, she said, had always been so sweet. “Who’s going to pay for the room?” she asked as the investigators left. “Not us!” they laughed.

At around midnight, Youssef agreed to give a statement. Sitting across from him in the PDI office, Berríos messaged Callie on her laptop as he prepared to explain himself to an investigator and a couple of other lawyers. It was just before 9 p.m. in Austin.

8:39 p.m. / Berríos: I need popcorn

I feel this is going to be a real movie jajajja

8:40 p.m. / Callie: this is the best day ever!!!!!!

8:40 p.m. / Berríos: I mean all his fantasy world . . .

DOminic [Rayner] is happy too and the palestinians everyone is celebrating haha

8:41 p.m. / Callie: . . . i wish you could record him so that I could listen to his side of the story. . . .

email me all your notes!!

8:42 p.m. / Berríos: he is saying he was never arrested before which is a lie he said he has only been a victim of blackmail

8:42 p.m. / Callie: omg

8:42 p.m. / Berríos: ok this is going to be nothing but horseshit

He was not responsible for Callie’s attack, Youssef stated. On the night in question, he’d told Callie that the purchase of the condos had fallen through, returned her deposit, and given her a backpack of money to take to Sabi. He’d then met up with two friends, Sam and George, who drank beer while he nursed a Fanta. Sabi had called him later that night to complain that Callie had gone to dinner instead of bringing home the money.

Youssef was calm, smiling as he recounted the evening. When asked, however, he couldn’t recall his two friends’ last names or their addresses or phone numbers. “That’s enough,” interrupted the prosecutor. “You’d at least have a phone number if you were friends.” Only then—and for only five seconds—did Youssef’s demeanor change, his face seizing in rancor. “His eyes were different,” Berríos later recalled—cold and hard. “I saw the real Youssef Khater for the first time.”

Just who the real Youssef was became a question for the psychologist who visited him at the Santiago Uno jail, where he was sent to await trial without bail. Youssef gamely answered the doctor’s queries, sitting for two forensic psychological interviews, a Rorschach test, and a diagnostic exam for personality disorders. Yes, he was born in Beirut, he admitted. His father, who was often drunk and physically abusive, was a welder; his mother worked in a hospital. They’d had five children, one of whom died tragically before the family emigrated around the time of the 1982 Lebanon War. In school, Youssef had been popular in part for his athletic abilities—he ran his first marathon at age eleven—but even more so, he said, for his “long eyelashes and raised brow.” He’d joined the infantry at age eighteen, when his parents separated, and then the marines—after which he became one of the few, he boasted, to be selected for the country’s special forces. When asked if he considered himself brave, he said, “If swimming with sharks is brave, then I’m brave.”

He insisted that he was not a criminal. “I help others or put others before myself,” he told the doctor. “I have a lot of goals and focus on them. I’m disciplined and happy.” Though his only concern after his arrest had been for the running gear he’d left at Sohad’s house—he’d become so agitated that Berríos had a bag of his clothes delivered—now he spoke sentimentally about his girlfriend. She was the most important relationship in his life, he said, beginning to cry. (“I’m a person who shows his emotions.”) But when it came to Callie, he was stony. “She drinks, uses drugs, takes one’s food without asking,” he said. “She is not a friend.” When pressed, his account of the night changed several times, and four months into his incarceration, in December, he finally admitted that, yes, he had struck Callie on the head. But he hadn’t intended to kill her, he stated, just confuse her into believing that he had returned her condo deposit, money he didn’t have. He had buried her to hide her from the night’s soccer fans.

“He displays narcissist, paranoid, and asocial traits,” wrote the psychologist in the final report. “He lacks empathy, and his relationship with others is instrumental.” It was unclear what parts of Youssef’s biography were true, and the interviews revealed what Berríos and others had already suspected: Youssef was most likely a psychopath. Though the term wasn’t applied officially—a formal diagnosis is given only after a thorough assessment most commonly involving the licensed twenty-item Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R)—he exhibited many classic traits. He was charismatic, egotistical, thrill-seeking, deceitful, and glib; prone to boredom and promiscuity; parasitic in his exchanges with others. Most important, he appeared to have no conscience.

First observed in 1801 by a French psychiatrist who described it as “insanity without delusion,” psychopathy has captured the public imagination since 1941, when the American psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley chronicled his interactions with psychopaths in a Georgia hospital in the classic The Mask of Sanity. The condition appears to have a genetic component: some experts, like neuroscientist Kent Kiehl, believe it arises from a general deficit in the brain’s paralimbic region—which regulates emotion, inhibition, and attention control—while others have theorized that it results more specifically from a defective amygdala, the part of the brain most responsible for fear conditioning. (Studies show that amygdalas in psychopaths are on average 18 percent smaller.) Whatever the cause, it creates the most disturbing kind of criminal: the expert manipulator who conceals “a grossly disabled and irresponsible personality,” wrote Cleckley, behind “a perfect mimicry of normal emotion, fine intelligence, and social responsibility.”

Many psychopaths feign behaviors and use “pity plays”—stories of personal tragedy or trauma—to distract others from their own lack of feeling and conscience. Incapable of love and numb to the emotions that spring from it, namely, empathy and guilt, psychopaths focus on short-term pleasures, a fact that often makes them careless about plans or consequences. This certainly seemed true of Youssef, with his spontaneous generosities and his many conflicting lies. In particular, his assault on Callie had been oddly careless. Why hadn’t he actually killed her? Could he not bring himself to, or was he simply sloppy?

That very question would define his trial, ten months after his arrest. In Chile, there are two types of charges for attempted murder: the greater is for those who do everything in their power to kill another and fail, the lesser is for those who plan out a murder but ultimately abort. Berríos was certain she could prove the more serious charge; as Callie remarked, “Why wouldn’t he want to kill me in that situation? The fact that he buried me alive and felt comfortable enough to go home seems evidence enough.” But doing so would require hours of testimony from Callie’s roommates, who were now scattered around the world. Berríos settled for the lesser charge. Youssef’s attorney, meanwhile, a lawyer named Roberto Kong, hoped to win him a suspended sentence, on account of Youssef’s being a first-time offender in Chile, allowing him to walk free.

On June 20, 2012, Berríos and Callie strode into the courtroom of Santiago’s imposing steel-and-glass Centro de Justicia. Callie’s recovery in Austin had been fitful. Sleeping on a friend’s couch and waitressing, she felt nauseated whenever she encountered anyone with Youssef’s attributes—his stocky build or thundering brows. When the local ABC affiliate requested an interview, she had turned it down, feeling shame over the attack. Opening her email filled her with dread, and her heart raced anytime someone walked up behind her. A therapist had diagnosed her with PTSD. Still, she had not let her parents cancel the family trip through southern Chile and Argentina that they’d planned before her assault, and in November 2011 they’d gone abroad together. Patagonia’s mountains, peaked like meringue against the saturated blue sky, reminded her why she had gone to Chile in the first place, and when her parents and brother returned to Texas, Callie stayed. For the next six months, she manned the reception desk at a little hostel in Puerto Natales, a way station to Torres del Paine National Park.

Now she found her way to a seat. She was eager to see how jail had weathered Youssef, and eager for Youssef to see her, resilient and strong. But when he emerged from a side door, handcuffed and wearing the same Under Armour clothing as the day he was arrested, she caught her breath. He looked as fit and radiant as always, if maybe a bit thinner. He flinched at the sight of Callie, his eyes sparking open before resetting into a stoic expression. He sat next to his attorney, and Callie found herself staring at the back of his closely shaved head. She pressed her hands against her legs to stop them from trembling.

Berríos, dressed in a black turtleneck, skirt, and heels, began quickly flipping through the evidence—Callie’s statement, her medical record, photos of the crime scene, the roommates’ statements, and the PDI report. When Youssef’s attorney argued that Youssef had no criminal history, Berríos was ready: she pulled out a statement from Danish prosecutors with their charges against Youssef. It was a gamble—the rap sheet was outside Chilean jurisdiction and not in the official language of the court—but the judge accepted it as proof. With the tap of the gavel, he pronounced Youssef guilty of attempted murder, for which he was sentenced to 541 days, and fraud, for which he got 61 days.

Six hundred and two days total, and Youssef had already served more than half of them awaiting trial. He would be out in a year. But then he’d be extradited to Denmark, where he’d face five more charges. Walking out of the Centro de Justicia, Callie took a deep breath of the biting winter air. She had won.

Callie stayed in Santiago, returning to work at Bridge Linguatec and doing her best to forget Youssef. She found a new apartment and made new friends. Occasionally, she traded friendly Facebook messages with Berríos—who had gone on to represent a 22-year-old accused of nearly decapitating a taxi driver with a knife—and her former roommates, who were still struggling to process all that had happened. Sabi, for one, scrubbed every picture of Youssef from her computer. It was too horrible, she said, to think that his friendship might have been entirely fake.

And then, in February 2013, there he was, in the headlines again, staring at Callie from the pages of Las Últimas Noticias. It had been only eight months since the trial. Youssef, reported the paper, had caught the attention of Frank Lobos, one of Chile’s most famous soccer players, who ran a sports rehabilitation program for inmates. From all appearances, Youssef had been a model prisoner: stuck in one of the oldest penitentiaries in Santiago, he had quickly ingratiated himself with inmates and guards alike by giving away sports clothing and administering acupuncture. (There were also rumors that he’d not only seduced a lawyer but also persuaded some pickpockets to wire him $1,500 each so he could arrange their travel to Denmark, where they might practice their craft on a more trusting populace.) Lobos, who had himself received treatment from Youssef for a strain in his gluteus (“It was very good,” he later recalled), lobbied to get him permission to compete in a marathon; the prison board granted the request. The newspaper photo showed Youssef in leggings and a neon-green Under Armour shirt, flanked by two guards, doing warm-ups.

Callie sighed. She could only hope that Denmark, where he was soon to be extradited, would deal with Youssef differently. In any case, she was ready to move on; she’d begun to realize that she didn’t want to teach English or be an expat forever. That August—shortly after Youssef’s transfer to Copenhagen—Callie boarded a flight back to Texas. The next year unfolded quickly: her parents helped pick out an apartment in Austin, and after some thought, she decided to put her love of science and teaching toward a degree in nursing education. She got certified as a nurse assistant, landed a job with Seton Hospital, and in January 2014 enrolled at Austin Community College to fulfill the prerequisites for nursing school. Though she still struggled with post-traumatic anxiety, she aced her anatomy and microbiology classes and was asked to become one of the college’s tutors.

And then, just as the fall semester was starting that September, Callie received an email from Berríos. It contained a link to a story in a tabloid from Costa Rica called Diario Extra. “Man Buries Woman Alive and Flees to Costa Rica,” screamed the headline. A marathoner named Youssef Khater, read the article, accused of attempted murder and fraud in Chile, had seduced a Canadian traveler in the town of Quepos and stolen $19,000 in life savings. He was wanted by the police.

Callie scanned the lines frantically, then searched online for further news. “Interpol Seeks Lebanese Marathoner,” read another Diario Extra headline. From what she could piece together, a thirty-year-old Canadian named Marie Taylor had been traveling in Costa Rica when, on July 27, at a market in Quepos, a handsome man had struck up a conversation. “I liked his charisma and generosity,” she told the paper. “It was love at first sight.” After kissing on the beach, he had asked her to stay in town another week, so she could take photos of him training for the extreme marathon known as La Transtica, which would kick off in Quepos in November. “He told me that he didn’t have a wife or children and that he’d been in the special forces in Denmark,” she said. It wasn’t until a few weeks later, after he’d drained her bank account and abandoned her in Quepos, that Taylor had learned who he really was.

As Callie would discover, the full story was even more complicated. Youssef had arrived in Costa Rica at the beginning of the year, just days after his release in Denmark. (He’d been acquitted of three of the five charges against him and freed after serving three months.) In the colonial city of Cartago, he had rekindled a friendship with Carlos Madrigal, a Costa Rican runner he had met in 2008, and Carlos’s daughter, Maria, a beautiful woman to whom Youssef almost instantaneously proposed marriage. He had then moved, without his fiancée, to Quepos, a two-and-a-half-hour drive away, to train for La Transtica and help instruct underprivileged youth at the local boxing gym. In early June, he had shown up at a marine electronics business in town owned by a Texas transplant named Todd Flanders. Introducing himself as Joseph Carter, he’d claimed to have been robbed of $10,000, along with all of his running clothes. He’d asked Flanders to place a $3,500 order for Under Armour sportswear on his behalf, promising that his sponsors would reimburse the money.

Flanders, a 44-year-old from Clear Lake City, was a salted-surfer type whose larger-than-life personality and generosity around Quepos had earned him the nickname Super Gringo. The kind of guy with two cellphones and a joke with everyone in town, he knew what it meant to depend on community; when his firstborn baby daughter had died five years earlier because of a heart anomaly, two thousand people had shown up for her funeral procession. Youssef had found his way to Flanders through a mutual friend, who vouched for him, so Flanders agreed to the loan. The men struck up a friendship, going together to the boxing gym, and eventually, when Flanders confided that he was separating from his wife and fighting for custody of their two-year-old twins, Youssef had offered a way to help with his legal fees: he would secure a batch of discounted cellphones that Flanders could resell out of his shop. Neither the cellphones nor the money for the sportswear ever arrived.

It was around this time that Youssef, still using the name Joseph Carter, introduced himself to Taylor. As Flanders later recounted, Taylor, the single mother of a nine-year-old, had traveled to Costa Rica for a yoga retreat, leaving her daughter with family for a few weeks so she could focus on regaining personal confidence and trust in other people. (Taylor’s first name, Sheena, was reported incorrectly as Marie by the paper.) Youssef was just the sort of presence she had been looking for: attentive and kind, he reserved them a room at a hostel, brought her breakfast in bed every morning, and treated her to meals and shopping. Charmed, she bought him the sports clothes he said he wanted. There were some peculiarities—like the time he remarked that he could kill her in the jungle and nobody would find her, or the time he pressed a pillow to her face in bed until she gasped for air, or the time she noticed that the name on his passport was Youssef, not Joseph—but when Taylor asked questions, Youssef countered that she had no sense of humor. Happier than she’d been in a long time, Taylor dismissed these things. And then, seventeen days into their romance, Youssef did not return to the hostel. When Taylor went to the bank, she was shocked to discover her account was at zero. Youssef had memorized her PIN, taken her bank card, and withdrawn as much money as he could from multiple ATMs during his breakfast runs.

Penniless, Taylor found Flanders by tracing the address on one of Youssef’s sports clothing packages. When she showed up at his store and shared her story, the two began to connect the dots by reading Danish and Chilean newspaper accounts online. Flanders immediately texted Youssef over Whatsapp. “How can you live with yourself after what you have done to this poor woman,” he typed. “She has a kid and you stole everything. . . . I was hoping it was just me, but to do this to a poor girl, that’s unforgivable.”

6:13 p.m. / Flanders: I will make sure that everyone in this world knows what you have done. . . .

6:14 p.m. / Carter: Tood stop i Will do the right thing. . . .

6:22 p.m. / Flanders: You stole from everyone including her daughter

6:22 p.m. / Carter: I never did that. Thats the lié tood. . . .

6:30 p.m. / Flanders: You need to have our money first thing in the morning you have until ten then I’m unleashing my tech computer guy. . . .

6:28 p.m. / Carter: Tood stop treahting me

6:32 p.m. / Flanders: No threats promises bro

6:29 p.m. / Carter: I can see

6:33 p.m. / Flanders: How are you going to pay us

“Give me time,” Youssef texted back. “I want to finish this more than you do. I don’t want this life.” But the next morning, Youssef went dark. “Where’s my money?” Flanders texted more than 55 times. When he got no response, he called Diario Extra with the story, then headed with Taylor to the Organismo de Investigación Judicial (OIJ), Costa Rica’s equivalent of the FBI, to report Youssef.

Callie’s heart raced as she thought about Youssef being free again. Where was he now? Would he come to Texas to seek revenge? Should she reach out to Flanders and Taylor? A few days after the headlines broke, her contacts in Chile took action: Medina spent a weekend creating a website on which to post every article ever written about Youssef, and Berríos contacted the OIJ offices to offer what insight she could. But the case gained little traction; much as in Callie’s case, OIJ officials dismissed the incident as a dispute among foreigners. Flanders and Taylor papered the city with “Beware of Joseph Carter/Youssef Khater” signs, but after two weeks and no inroads, Flanders bought Taylor a plane ticket so she could reunite with her daughter in Canada. He would pursue Youssef himself, he decided: he’d learned of the fiancée in Cartago, and he planned to track her down.

Weeks passed, and Callie waited for news of a break. In some ways, she felt, she had been a victim of others’ inaction—if any of Youssef’s Danish or Palestinian victims had been more proactive, she might have been spared her ordeal. She grew anxious knowing that Youssef was still wreaking havoc: after Flanders revealed Youssef’s true identity to his fiancée, Youssef retaliated by telling Flanders’s wife that he’d been hired to steal their twins and take them out of the country—a lie that kept Flanders from seeing his daughters for two months. Taylor, meanwhile, had gone almost entirely silent; she stopped responding to journalists’ queries and delayed providing the authorities with her bank statements. (Taylor did not respond to an interview request for this story.)

That December, sitting at a coffee shop on her day off from the hospital, Callie decided to compose an email to Taylor. “My name is Callie Quinn,” she began. “I am not sure if you are familiar with who I am, but I was also a victim of Youssef. . . . I don’t want to presume your feelings at this time. All I know is how I felt after the fact and perhaps you share some of these sentiments. I felt foolish. I felt duped. I was embarrassed. . . . But this is not how I should have felt and I no longer do.”

Callie paused. Outside, the sun was shining brightly. Callie continued. “As victims, we are now given the responsibility to do what we can to prevent him from continuing. Although we did not ask for this responsibility, it is ours nonetheless. The word ‘victim’ does not have to connote silence and weakness. Instead it should mean survivors and seekers of justice. I know how tempting it is to want to distance yourself from the situation and ignore it. But I will tell you, with time, you cannot run away from what happened, it will always be with you. All you can do is directly face it and do what you can to prevent it from happening again to someone else.”

She sat on the note for several days before finally pressing send. A day passed, and Taylor did not respond. A week passed, then another, and still nothing. Then came shocking news: Flanders, who had recently made a few overtures to get in touch and planned to call Callie before the end of the year, was dead. The loss of his late daughter and the fight for custody of his little twin girls had overwhelmed him, and he had hanged himself. The town of Quepos was reeling in shock. “I LOVE MUCHO MUCHO MI SUPER GRINGO,” wrote a friend on his Facebook wall.

A month later, on January 9, 2015, Taylor’s name popped up in Callie’s in-box. The subject line read, “YK—FYI.” Callie nervously clicked open the note. It was blank except for a new Diario Extra link.

The term “psychopath,” coined in Germany in the 1880’s, literally means “suffering soul.” It’s a beautiful characterization, but the term is a misnomer, because psychopaths, unlike victims of other mental disorders, do not feel discomfort or distress on account of their condition. “Psychopaths are rational and aware of what they are doing and why,” writes Robert Hare, who devised the Psychopathy Checklist, in his book Without Conscience. “Their behavior is the result of choice, freely exercised.”

In fact, if a psychopath feels any degree of misery, it is because of others. “If he gets angry because he doesn’t want you to go out,” says Elizabeth Leon Mayer, a psychopathy researcher in Chile and a protégé of Hare’s, “he’ll say, ‘You make me angry because you want to go out.’ Not ‘I get angry because I don’t want you to go out.’ So if he does not accept responsibility for what he feels or does, he doesn’t feel guilty for his selfish actions, and he doesn’t feel there’s any reason to change his behavior.”

This moral vacuum presents an unusual challenge for the medical and legal fields. It is estimated that between 12 and 22 percent of the world’s criminals now sitting in prison are psychopaths. If these prisoners are genetically incapable of change, what can they be held responsible for, and what should be their treatment or punishment? “You can’t teach a psychopath to become empathetic,” says Mayer. “So really it’s about intervention.” If a psychopath can be persuaded that inflicting harm isn’t in his best interest, in other words, then maybe he’ll stop.

But this intervention, requiring hours of one-on-one counseling, is costly, and appears to be most effective on young minds. (In a 2006 study in the U.S., 141 juvenile psychopathic offenders who underwent intensive talk therapy were half as likely to violently recidivate as a control group.) For more-hardened criminals, the investment is difficult for policy makers to rationalize. “In Chile we say, ‘Bailar con la fea,’ or ‘Dance with the ugly one,’ ” says Mayer. “When you treat aggressors, you have fewer victims. But that approach doesn’t win you votes.” Neuroscientist Kent Kiehl has also weighed in. “The average psychopath will be convicted of four violent crimes by the age of forty,” he told the New Yorker in 2008. “And yet hardly anyone is funding research into the science. Schizophrenia, which causes much less crime, has a hundred times more research money devoted to it. . . . Because schizophrenics are seen as victims, and psychopaths are seen as predators. The former we feel empathy for, the latter we lock up.”

In the case of an offender like Youssef, these questions are further complicated by a difference in approach by country. Though the PCL-R is used in places as disparate as Denmark, Chile, and the U.S., there’s no consensus on how a diagnosis determines culpability. “In Denmark, if someone is found to be psychopathic, there must be a second opinion from a board of university psychologists,” explains Bjørn Elmquist, a lawyer and two-time member of the Danish parliament, known for his left-leaning politics. (Youssef wrote to Elmquist from Chile to ask for legal representation, but then dropped all contact.) After that, the general prosecutor may propose hospital treatment—for two to five years—after which there may be a retrial. In Chile, as in the U.S., a psychopath is considered fit for trial because he can discern between right and wrong, but life sentences are limited to a maximum of forty years. “Chileans feel there’s no point in punishment if there’s no hope that someone can get better, and we cannot punish the person for who he is,” explains Berríos. “The only punishment we can accept is for past conduct. We cannot put a person in custody because he will commit more crimes.”

And then, simply, there is the matter of actually catching the psychopath, as Callie thought when she clicked on Taylor’s link. There, in Diario Extra, was Youssef again, this time in handcuffs. He looked, for once, a little washed-up, in a taupe T-shirt and dark jeans, with thinning hair. Two Costa Rican brothers to whom Youssef had tried to sell cellphones had become suspicious of him; after finding Diario Extra’s coverage online, they had called authorities upon spotting him in San José in January. But after questioning Youssef about his alleged frauds, OIJ officials determined that there was not enough evidence to charge him. In Taylor’s case, Youssef had once withdrawn money with her permission, and there was no way to prove he had stolen the rest. The OIJ recommended dropping the case.

Sitting in her apartment this past April, beneath a Chilean woodcut poster, Callie imagined that Youssef was likely still walking the streets of San José, chatting up strangers and proposing deals. The newspapers in Costa Rica had dubbed him “the lady charmer.” She knew by now that she would probably never feel closure. “He needs to be institutionalized,” she said, after a few moments. “I acknowledge that what he does is basically out of his control, but he needs to be under supervision for the rest of his life in some capacity.” She closed her eyes. “And if that’s in jail, and it’s a horrible condition for him, that’s fine by me,” she continued. “I want him to have a horrible, difficult life. I don’t feel bad saying that.”

She shuddered. Almost four years since the attack, she was still haunted by the last time she had seen Youssef in person, at his trial in Chile. As the judge read his sentence, Youssef had stared straight ahead, listening impassively. Then, just before the guards ushered him out, Youssef had twisted around, looked at her with his luminous brown eyes, and winked.