In early December, when I drop by Bill Wittliff’s office just off Sixth Street in the heart of Austin, he is, as he puts it, “a little busy.” On his desk are stacks of notes for two screenplays he is writing for major studios—one about the building of the transcontinental railroad, the other about the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the sixteenth century. Next to those stacks is a screenplay about a runaway slave; although he has already sold it, he feels it could use some polishing.And those are just a few of his projects for the day. He tells me he needs to take some time to peruse the first copies of his new book, Boystown: La Zona de Tolerancia, which have just arrived. The book is a collection of riveting photographs that Wittliff began gathering in the mid-seventies from itinerant Mexican photographers who took pictures of sad-eyed prostitutes and their drunken, leering customers in an unnamed town just south of the Texas-Mexico border. Then, for a planned book of his own photographs, he needs to spend a few minutes flipping through some of the eerie, slightly blurry black and white portraits of bullfights, cowboys, and religious statues he took with cameras that he jury-rigged himself to diffuse light in startling new ways.

Of course, he can’t attack any of these tasks until he finishes talking with the woman seated on the other side of his desk. She is Connie Todd, who helps him oversee his two collections housed at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos, just south of Austin: the Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and Mexican Photography, with around 8,700 photographs, and the Southwestern Writers Collection, which includes, along with historic manuscripts and first drafts of novels, such Texas literary memorabilia as the white suit worn by J. Frank Dobie when he gave lectures, the old Smith Corona used by Larry L. King to write The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, and a book of lyrics written by Willie Nelson when he was eleven years old.

Dressed in his favorite uniform—blue jeans, a button-down shirt with a fish print, and white tennis shoes that always look nice because he never runs in them—Wittliff pulls at an unruly tuft of gray hair flipping over one ear and starts to discuss upcoming exhibits with Todd. Yet the phone never stops ringing, and Wittliff often picks it up on the first ring. There’s an agent, a writer, a real estate broker, a lawyer. “What’s going on?” Wittliff says every time, genuinely interested in what the other person has to say.

Suddenly, the front door opens and in walks a struggling young photographer who just wants to say hello. Wittliff stops everything, gets up, offers the photographer a few minutes of reassuring conversation, then walks him back to the front door and shakes his hand good-bye.

“You know that this is the way he operates every day,” says Todd, who was Wittliff’s personal assistant for sixteen years before she began working full-time on the collections at Southwest Texas State.

“And he still gets everything done?” I ask.

“Everything.”

“I feel a little sick to my stomach,” I say—a reaction that Todd assures me is not unusual among self-absorbed, pseudo-artistic types who, upon meeting Wittliff for the first time, begin to realize just how little they are accomplishing with their own careers. Wittliff is Texas’ Renaissance man, as versatile as a utility infielder in baseball. He is a writer, a photographer, a book publisher, a film producer, a book collector, a historical archivist, a pen-and-ink artist, and according to his closest friends, a poker player of such skill that he could make a living on seven-card stud alone if he ever decided to move to Las Vegas. And now, at the age of sixty, he seems to be hitting his stride. Although Wittliff has been revered in Hollywood circles since he wrote and produced 1989’s Lonesome Dove, the Emmy-winning television miniseries based on the Larry McMurtry novel, he is finding himself inundated with offers from producers and directors, thanks to the success of last year’s film The Perfect Storm, which he wrote based on the Sebastian Junger book. (So far the movie has grossed more than $340 million.) He was asked to write the screenplay about the transcontinental railroad, for instance, at the behest of Martin Scorsese, who plans to direct the film, and Steven Spielberg, who plans to produce it. When he let it be known that he wanted to write about Spaniard Hernán Cortez’s conquest of Mexico, various studios immediately began bidding for the rights to produce it. “Let me tell you, it’s not only rare for someone at the age of sixty to be at the top of the screenwriting game, it’s almost unheard of,” says Bud Shrake, a novelist and screenwriter and Wittliff’s longtime friend. “Very few writers age sixty or over can even make a living at screenplays. There’s Larry Gelbart, Elaine May, William Goldman, Bill Wittliff—and that’s about it.”

And it’s a safe bet that he’s the only screenwriter of any age who can juggle so many other projects at the same time too. “I didn’t exactly plan to be doing so much,” Wittliff tells me in his deep, twangy voice, wagging a cigarette between his fingers. “If you want to know the truth, I never had any totally conscious plan about where my life would go.” He gives me an apologetic grin as he reaches for the telephone that’s ringing once again on his desk. “I don’t even have a plan now. I just sort of go where the wind blows me.”

If he wanted to, Wittliff could play the role of the bearded sage. He could sprinkle his conversation with references to all the writers and photographers he knows. He could fill you in on just how important he is in Hollywood, how no one turns him down for meetings, how he’s gotten at least 25 calls in the past few months from producers willing to pay him stratospheric sums for one of his screenplays. Yet he is almost ridiculously without pretense, as amiable as a large, shaggy dog who shows up in your back yard every now and then just to nose around. Each weekday morning, he goes to his office—a converted two-story house that O. Henry once lived in—where he drinks coffee nonstop, smokes one cigarette after another, and greets a steady stream of drop-in visitors, from hopeful young WPW’s (writer-photographer-whatevers) to such luminaries as actor Tommy Lee Jones, who occasionally arrives in a pick-up truck, barges through the door, and demands that Wittliff have lunch with him. Eventually, Wittliff does get around to dictating part of a screenplay to his newest assistant, Mara Levy, a delightfully irreverent young woman who happens to be a daughter of Texas Monthly’s publisher. She doesn’t hesitate to make a gagging gesture, her index finger pointing inside her mouth, whenever he delivers a line she doesn’t like. Utterly unoffended, Wittliff gives her some more lines, then dismisses her so that he can write some notes to himself on a pad.

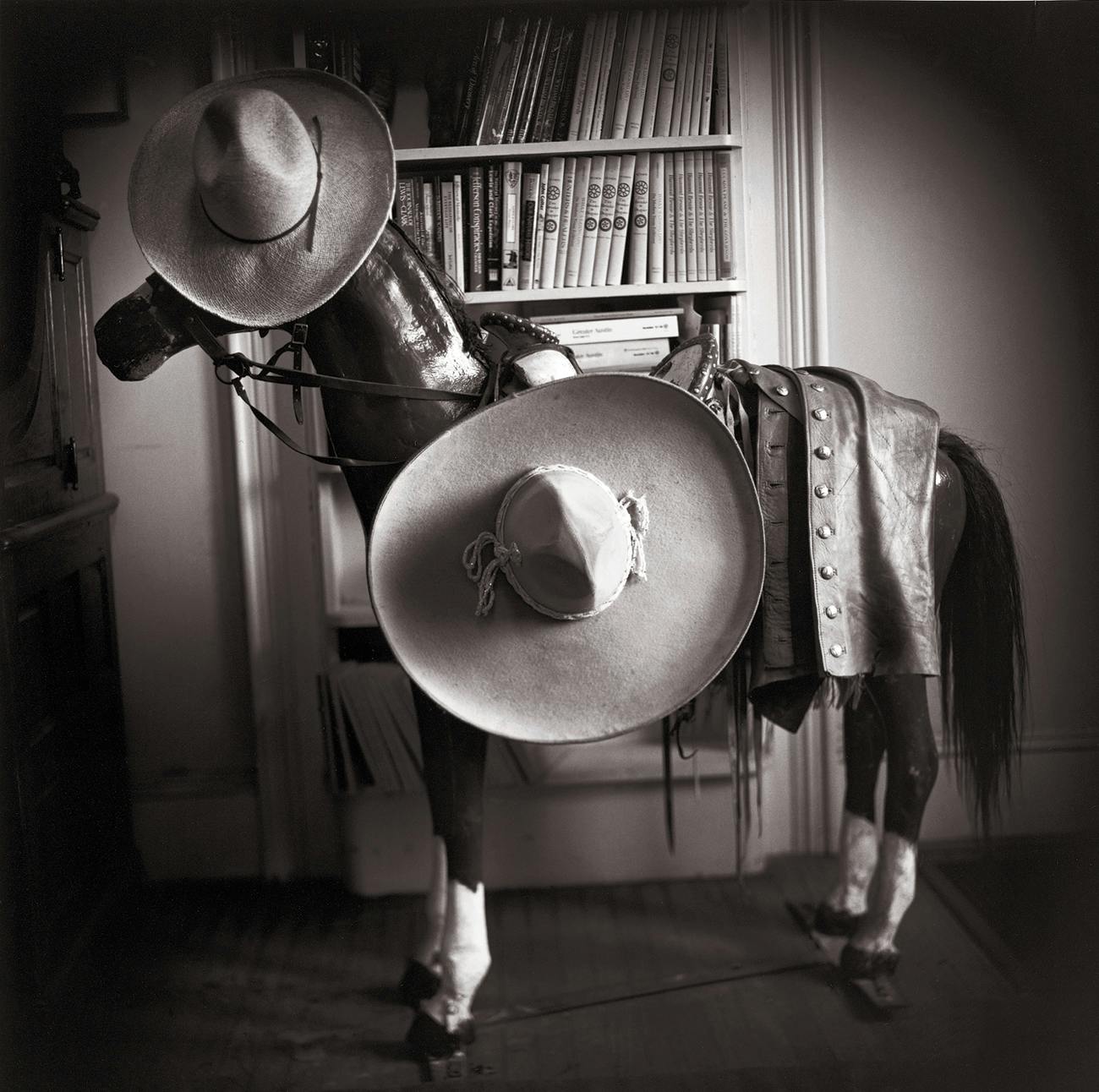

Wittliff’s office looks like a combination museum and rent-by-the-month storage unit. On the walls are works by a variety of Southwestern artists and photographers, a rare gravure print of a J. Frank Dobie portrait by Tom Lea, and photographs taken by Wittliff himself of men who have meant something to him (among them Willie Nelson, essayist John Graves, and actors who were in Lonesome Dove). A large antique bookcase is filled with a couple hundred old books (he has thousands more at his home and at Southwest Texas State), and on the floor are boxes of personal mementos, some dating back to his grade school days. The only modern-looking thing in the room is an aqua computer, which Wittliff bought more than a year ago to buy old photos on eBay. The only problem is, he has never learned how to log on to eBay, so the computer just sits there. “But it’s a beautiful damn thing, isn’t it?” he says.

Wittliff’s modus operandi would drive a time-management expert crazy. Some days, when he seems deep into one of his screenplays, he’ll impulsively head upstairs to his darkroom and start developing photographs. Or he’ll pack up his camera gear and set off on a photography expedition. Or he’ll go hunting for new treasures to add to his Southwest Texas State collections, items ranging from the historically important to the comically kitschy. With the help of a benefactor, he recently spent $45,000 for what may be the last available copy of La relación y commentarios, the 1555 travelog by the shipwrecked explorer Cabeza de Vaca, which is considered the first book ever written that describes Texas. Back when his buddy Willie Nelson was being sued for $16.7 million by the Internal Revenue Service, Wittliff once took an afternoon off and drove out to the singer’s Pedernales recording studio just to swipe the IRS sticker on the front door declaring that the studio was being confiscated for back taxes.

And then there’s the enormous amount of time Wittliff will devote to one of his publishing projects. The creation of Boystown: La Zona de Tolerancia is a classic Wittliffian venture. In the early seventies, while researching a screenplay set in Mexico, Wittliff visited Boystown, a red-light district in a Mexican border city where he planned to set a scene. He befriended the photographers who worked the cinder-block whorehouses and charged customers a couple of bucks for a “souvenir” of their evening among the prostitutes. Before the night was over, they took him back to the tiny studio they shared, where he saw a pile of negatives on the floor. He picked one up and held it to the light. Then, with a gasp, he picked up another.

Although the photographs were nothing more than quick snapshots, Wittliff realized that they revealed a sometimes humorous, sometimes merciless world of lust and cheap happiness that no one else had come close to capturing. (When Wittliff himself had tried to take photos in Boystown one day, he was nearly assaulted by the prostitutes.) There were shots of fraternity boys posing like bandits; Mexican laborers posing like rich businessmen; aging, naked prostitutes posing with chins proudly raised in an attempt to maintain their dignity. Wittliff cut a deal with the photographers to buy their negatives, then he cut a deal with a friend to slip the negatives across the border. In all, he collected more than seven thousand negatives, and off and on for the next 26 years, he cleaned those negatives, then printed the photos and retouched them, sometimes spending six or seven hours on one photo alone.

Although Boystown: La Zona de Tolerancia will not get even a fraction of the attention that will be lavished on whatever his next movie is, Wittliff seems as proud of this project as of anything he’s ever done. “Why did Ispend so much time on these pictures?” he asks rhetorically, then pauses, as if he’s not sure of the answer. “There was no way I couldn’t work on them. They were this incredible human document, revealing to us lives that we never before knew.” He pauses again. “Every time I looked at these photos, I saw stories that needed to be told and that needed to be preserved.”Wittliff is almost obsessively driven by this need to tell and to preserve. “It’s what sets him apart from everyone else I have ever known,” says Keith Carter, the well-regarded East Texas photographer who has been a long-time contributor to Texas Monthly and is a close friend of Wittliff’s. “Bill is not only a great storyteller, he has a great empathy for other people’s stories. He loves to find the narratives that run through our lives.”Although he has a reputation among studio executives as a wily dealmaker—”Wittliff is one of the few writers I know who likes going to breakfast with the Hollywood suits and negotiating,” says Shrake—he also keeps one foot firmly in the past. “There’s something about him that seems to be a little bit out of his time,” says Connie Todd. “It’s as if he had been raised at the turn of the century.” He was born in 1940 in the tiny South Texas community of Taft. When he was only two years old, his mother left his father, a raging drunk, and got a job as a 24-hour-a-day switchboard operator making $30 a month. Wittliff and his older brother lived with her in a little room adjoining the switchboard office, and they would listen to her conversations with the townspeople. After they moved to another small town, Edna, Wittliff’s main childhood entertainment was walking into town and listening to the owner of the hardware store tell stories. He also learned to tell stories himself. He told his school classmates, for instance, that his father was a “Flying Tiger” who had been killed in combat in World War II. Everyone believed the story, Wittliff recalls, until his father showed up at school “toilet-hugging drunk,” telling the principal that he had come to wish his son a happy birthday.

Wittliff spent his high school years in the Central Texas town of Blanco, where the family had moved when his mother married a rancher. He was the quarterback of the high school football team, a starter on the basketball team, and the class cutup who always had a funny story or a joke to tell.

But even then Wittliff felt a need to keep a record of the details of his life. He kept just about everything—his notes, letters, photos, school papers. When he was fifteen, he tried to sneak into a sold-out Elvis Presley concert in San Antonio by climbing a tree and attempting to get into the auditorium through a second-floor window. It turned out to be a window in Presley’s dressing room. Presley, who was then at the dawn of his career, was so charmed by Wittliff that he wrote a note on a napkin telling the security guards to let Wittliff and his buddies into the auditorium. Wittliff spent the rest of the evening carefully holding the napkin, sensing that it would someday be important. (It is now framed and stashed in his office.) “Maybe I kept all those things because it was my way of telling myself that I mattered,” he says. “Maybe that’s why I liked telling stories about myself—telling stories was my way of trying to matter.”

One Christmas when he was in high school, Wittliff received a present from his aunt who lived in Houston. It was J. Frank Dobie’s Tales of Old-Time Texas, a folklore collection. In the book was a story titled “The Wild Woman of the Navidad,” about a runaway slave whose footprints were often seen in the settlements along the river. Wittliff realized that this was the same story he had heard the hardware store owner tell years before. “The book absolutely set me on fire,” he says. “Until that moment it never occurred to me that books and writing could come out of your own experience, your own soil.” Wittliff began to think that he too could become a writer. “Prior to that, the thought never occurred to me,” he says. “I was so ignorant during my childhood that I literally thought every book in the world came from someone living across the great ocean.”

Wittliff started sending ideas to the best television dramas of that era—Kraft Television Theatre, Playhouse 90, Robert Montgomery Presents. “I wrote down a million ideas for those shows, and they were all basically variations of the same theme: Three junior high or high school boys play hooky from school, which I just happened to be doing at the time, and each time they would end up doing something good for the world. They’d capture a bunch of cattle rustlers or they’d free a brilliant scientist who had been kidnapped by Russians. Needless to say, none of my submissions were accepted.” He also tried to get published in Reader’s Digest. He submitted an article for its column My Most Unforgettable Character. The story, entirely invented by Wittliff, was about his close relationship with Lyndon Johnson, then a U.S. senator, who had a ranch near Blanco. When that article was rejected, he sent several made-up quotes—which he claimed he had heard LBJ say—to the Quotable Quotes section. Reader’s Digest turned him down again.

After graduating from high school, in 1957, Wittliff enrolled in and dropped out of four universities in his freshman year alone before finally settling on the University of Texas. He majored in journalism but wasn’t a particularly dedicated student. For one thing, he didn’t want to learn to type. One semester he put his arm in a sling every time he went to the journalism building in order to avoid having to participate in a typing class. Perhaps his biggest claim to fame during his university days was the horseshoe-shaped bar he built in his room at the Kappa Sigma fraternity house. At night, he and his roommate would turn the room into a gambling den, where Wittliff won most of the poker games and sold cheap Scotch that he had poured into empty Chivas Regal bottles. Among the regular visitors to his gambling den, he says, was Frank Erwin, who was the fraternity’s legal adviser and later became the chairman of UT’s board of regents. He did get a part-time job with the company that owned the pulp magazines Frontier Times and True West, which was then based in Austin, but his work there didn’t suggest that he was destined to become one of the bright lights of Texas arts and letters. He drew a few sketches of cowboys, Indians, rifles, and such for the magazines, and he did get one short piece published, titled “The Bandana, Flag of the Range Country.”

Yet Wittliff was determined to make some kind of mark. After graduating from UT, in 1963, he married his college sweetheart, Sally Bowers, and landed minor jobs, first as the business and production manager for the Southern Methodist University Press, in Dallas, and later as a salesman for the University of Texas Press, in Austin. One day he visited J. Frank Dobie, who lived in Austin, and told him that he was planning to start his own book imprint, which he was calling the Encino Press. He said that he wanted the first book he published to be one by Dobie himself. Amused by the young man’s passion, Dobie agreed to let Wittliff reprint one of his older stories, royalty-free.

Using his poker winnings as seed money, Wittliff and Sally ran the Encino Press out of their Austin home. Although the company barely got by, its books, almost all of them about Texas, were well received. Wittliff used Encino as his calling card to meet the region’s best writers, including Larry McMurtry, who agreed to let Encino publish a collection of his essays that became the highly praised In a Narrow Grave.

Wittliff also decided, almost on a whim, to become a photographer. Knowing nothing about cameras except how to focus and click, he headed to Mexico in the late sixties to photograph vaqueros working a roundup on a ranch. The pictures immediately created a sensation in photography circles. “When I looked at those photos,” says Keith Carter, who was then just beginning his own career, “I realized I was looking at someone who knew how to tell a story through images. I said, ‘This is what I want to do too.'”

“If there was a secret to my success, it was that I was so ignorant,” Wittliff tells me. “Really, there is something to be said for the phrase ‘Ignorance is bliss.’ If I had known everything I was supposed to have known about book publishing or photography, I sure as hell would have been too afraid to try it.”

It was in that same spirit of blissful ignorance that Wittliff decided to tack on a third career—screenwriting. He had never seen a screenplay when he sat down in the early seventies to start writing a movie based on a story his grandfather had told him years before. He didn’t use an outline; he simply wrote down whatever came to him next. Within a month he had a screenplay. Bud Shrake saw it sitting on Wittliff’s desk, read it, and asked if he could show it to his agent. The script eventually was given to the producers of The French Connection, who loved it, and a few years later it appeared as Barbarosa. Starring Willie Nelson as a onetime outlaw hunted down by a vengeful family, it was praised for its intriguing revelations about human nature by such noted critics as The New Yorker‘s Pauline Kael.

Wittliff quickly landed another assignment, rewriting the script of The Black Stallion, and by the early eighties was writing like a man possessed, finally getting out all the stories that had been rattling around in his head for decades. He wrote one movie based on his mother’s life as a telephone operator (Raggedy Man, starring Sissy Spacek), another about the life of country musicians on the road (Honeysuckle Rose, again starring Willie Nelson), and a third about a family nearly losing its farm (Country, starring Jessica Lange and Sam Shepard). Then came the screenplay for Lonesome Dove, which many critics hailed as one of the greatest western films ever made, some saying it would have won an Oscar if it had been made as a feature film rather than a miniseries.

Wittliff suddenly found himself on Hollywood’s rarefied A-list, being offered eyeball-popping amounts of money to move to Los Angeles and work on movies or television series. Yet he refused to leave Texas. He already had a fourth career in mind: literary archivist. A few years before Lonesome Dove, he had received a call from a former secretary of J. Frank Dobie’s asking if he might be interested in buying the great man’s desk, which she had inherited. Wasting no time, Wittliff met her at Dobie’s house, wrote a check for the desk, and then noticed about thirty cardboard boxes in a corner of the room. When he learned that they contained papers and other items remaining from Dobie’s estate—from the writer’s favorite books to his beloved white suit to the shoes that had been specially made to compensate for his bent feet—Wittliff pulled out his checkbook again.

“When the Dobie material came to me, I knew what I was going to do,” he says. “Sally and I wanted to create something that we would call the Southwestern Writers Collection. It would be a place you could go to see the artifacts of Texas writers who had struggled throughout their lives to find just the right word or the right phrase, who wanted to express a feeling, who needed to tell a story. I wanted a place that might inspire a new group of young Texas writers. I wanted them to sense that they were part of a brotherhood and sisterhood that went back all the way to Cabeza de Vaca, that continued with Dobie, and that continues today.”

Once the Southwestern Writers Collection was established in 1986, Wittliff turned his attention to a fifth career: photography collector. In 1996 he and Sally established the Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and Mexican Photography, his hope this time being to inspire other photographers. Then, not long after the gallery’s opening, he decided to resurrect his career as a publisher (the Encino Press now sells only its backlisted books). In 1996 he started the Southwestern Writers Collection literary series and the next year began publishing photography books under a new Wittliff Gallery imprint, both through an arrangement with the University of Texas Press.

By now, Wittliff has made so much money through his screenwriting that he probably never has to work again. He’s added to his wealth through some shrewd investments in Austin real estate. His and Sally’s two children are grown, and Sally has become a prominent Austin lawyer. Besides their Austin house, the couple has vacation homes on Padre Island and in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. But when I suggest to Wittliff that no one would fault him if he trimmed back his schedule and took more time off, he chuckles and says, “What the hell are you talking about?” He says he has many more screenplays left in him, along with more books of photos and perhaps a novel. “When I hear younger writers say that Texas has run out of good stories, I tell them to think again. There are still so many stories out there to tell.” He finds it especially rewarding that the most recent screenplay he has sold, the one about the runaway slave, is based on the story he first heard more than fifty years ago as a little boy at the hardware store and later read in Dobie’s Tales of Old-Time Texas. “I’ve never been more excited about everything that’s going on,” he says. “I guess the wind is still blowing out there.”