This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

One of the pleasures for me of making my Texas films is riding around the state with the director and the art director, looking for towns that can help establish a sense of late-nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century Texas, towns like Waxahachie, Palmer, and Ennis.

Venus, in North Texas, is a particular favorite. We used it in filming 1918 and On Valentine’s Day. Venus’ Main Street has a number of brick buildings, half of them in use, the rest abandoned. On one corner is a brick building that had been the local bank and was used as one of the banks held up in Bonnie and Clyde. Venus once was a prosperous cotton town, but cotton has moved on, and so have the people.

You can find Venus’ counterparts all over rural Texas, abandoned or half-abandoned Main Streets with buildings that were once useful and handsome, now left to decay. Thinking of those houses and towns, I am reminded of these lines from Robert Frost’s poem “Directive”:

There is a house that is no more a house

Upon a farm that is no more a farm

And in a town that is no more a town.

Last spring I was in Galveston to attend a festival of my films. At a party I met Keith Carter, who had asked me to write an introduction for a book of his photographs of rural Texas. He had the photographs with him, and I was very taken with them.

According to his wife, Pat, on the eve of their tenth wedding anniversary Keith suggested an interesting way to celebrate the event. “What about a trip all around Texas,” he proposed, “leaving the highways, the Interstate 10’s or Interstate 35’s, and messing around the back roads and taking pictures?” That suited her fine, so they got out maps and found towns to visit with names that intrigued them. A moving company’s master list of Texas towns proved useful, and friends gave the Carters a sesquicentennial set of maps for all the counties in Texas, showing all the churches, byroads, and cemeteries. And so they began their year-long anniversary celebration by visiting those towns and taking pictures of what interested them.

Much of the traveling was done over a summer, with other trips on weekends and holidays. They traveled many miles, many weekends, Keith taking pictures and Pat making penetrating notes and observations of people and places. She writes of Looneyville, in Nacogdoches County: “On the counter at the Looneyville store they keep an open spiral notebook which serves as the town newspaper. Every day they write the date at the top of a fresh page. Anyone who has news comes by and writes it in the book.”

Of Dialville, in Cherokee County: “Wanna buy a town? This one is abandoned but intact. Two-story brick building was the bank, adjoining one-story brick units housed grocery, drugstore, post office. Red dirt road runs up the hill alongside the bank. Iron plate on step bears date 1894. It’s a monochromatic scene. More than ninety years of red dust has settled and turned everything the same color. As we drove into town I noticed an old man sitting on the porch of a once grand house. Same man now has circled us twice, driving by slowly in his car. On the third pass, I try a wave and a smile and he pulls up beside me under the big sycamore tree in front of the bank. He is Clarence Moore, born in that big house more than seventy years ago. His father was the town doctor.

“Clarence’s car, inside and out, is the same rich red color as everything else here. Clarence, himself, wears the stain on his hands and fingernails. He stands quietly and then begins to speak to me about the town as he knew it in his childhood and youth. There is no attempt in his narrative to entertain or amuse, and our conversation has a peculiar, stately rhythm with long moments of silence. I feel a great solemnity. If I am to understand, I must listen to his pace. It is a melancholy and dignified grief. Clarence is keeping a death watch for this town.”

A persistent and pleasant memory of my boyhood in the twenties is riding around with my grandmother and grandfather in their Studebaker to check on their farms scattered over Wharton County, in Southeast Texas. The roads then were dirt or gravel, and it was difficult to visit all the farms in one afternoon or even one day, since every farm visited meant getting out of the car and talking with the tenant farmers, inquiring about their health and the health of their wives and children, and walking a ways into the fields to inspect the present state of the cotton or corn crops.

To get to those farms (seven in all), we would pass tiny, dwindling towns with names like Iago, Burr, Glen Flora, Lane City, Egypt, and Hungerford and one completely deserted area with no sign of a store, building, or house, about which my grandfather, when passing, always remarked that somewhere in this vicinity (he was never exactly sure just where) had been a town—now vanished completely—called Preston. How that came to happen was a mystery to him, and I was never able to find anyone who knew.

Every now and then we would ride 25 miles to East Columbia, in Brazoria County, where my grandfather was born in 1865. When I was growing up, there was a photograph in my home of a large, impressive house that stood on the banks of the Brazos River. There was a circle of live oaks in the front yard. Also in the yard were a number of children and three adults, some of them playing a game of croquet. This was the home of my grandfather’s parents—a house he lived in until he went off to college. After his mother died and the other children moved away to other towns, it was abandoned and finally taken down.

Leaving the highway at West Columbia to take the back road to East Columbia, we would pass a store—deserted, surrounded by weeds, roof falling in—that my grandfather said he once clerked in as a boy and a young man. Next, we would see an empty lot with live oaks, and he would say, “This is where our house used to be, and if it had remained standing, the Brazos River would have gotten it, because it has taken the half of the yard it once stood on.” And then he would always add, “This was a thriving river town once, East Columbia. Boats went from here up the river. Once . . .” “Once . . .” This was a word I heard often—once this was so, and once that was so.

All that then remained of East Columbia was seven houses, the abandoned store, and the cluster of diminishing live oaks. I would try to reconstruct that house, pushing the river back to its old boundaries, trying to imagine that day when the picture of the house was taken with my aunts, uncles, and cousins standing primly dressed in their best clothes. Some of them had since died, and those who were living returned to East Columbia with their children and grandchildren as infrequently as we did, gathering mostly for weddings and funerals.

And so, riding around with my grandfather and grandmother and passing these dying and forgotten towns, or towns that never were more than a store or two, “why” was added to my vocabulary. Why did this town never prosper? Why was it never more than a church, a grocery store, and one or two houses? Why did the people leave this town and go to another place? Why?

My grandfather would patiently explain how towns came to be and for what purpose, how circumstances changed so that towns were abandoned, how some towns, like Egypt, were never meant to be more than a store or two, serving the tenant farmers and the one or two families who owned all the surrounding farmland. He said that the railroad in the beginning almost went through Glen Flora instead of Wharton, and if that had happened, why . . . Then he would pause and we would all contemplate what that would have meant. For Wharton in those days, God knows, was no metropolis, but it was the county seat; it had the courthouse, a respectable Main Street, two railroad stations; and if Glen Flora had gotten the railroad station instead of Wharton, it would have had the main street, the courthouse, and the two depots, instead of a handful of stores that dwindle year after year.

Katherine Anne Porter takes us to an earlier Texas in her story “Noon Wine.” She tells us in her notes about writing that story: “This summer country of my childhood, this place of memory, is filled with landscapes shimmering in light and color, moving with sounds and shapes I hardly ever describe, or put in my stories in so many words; they form only the living background of what I am trying to tell, so familiar to my characters they would hardly notice them.” And yet, because of her selection, her choices, “Noon Wine” becomes one of the great short novels in American literature.

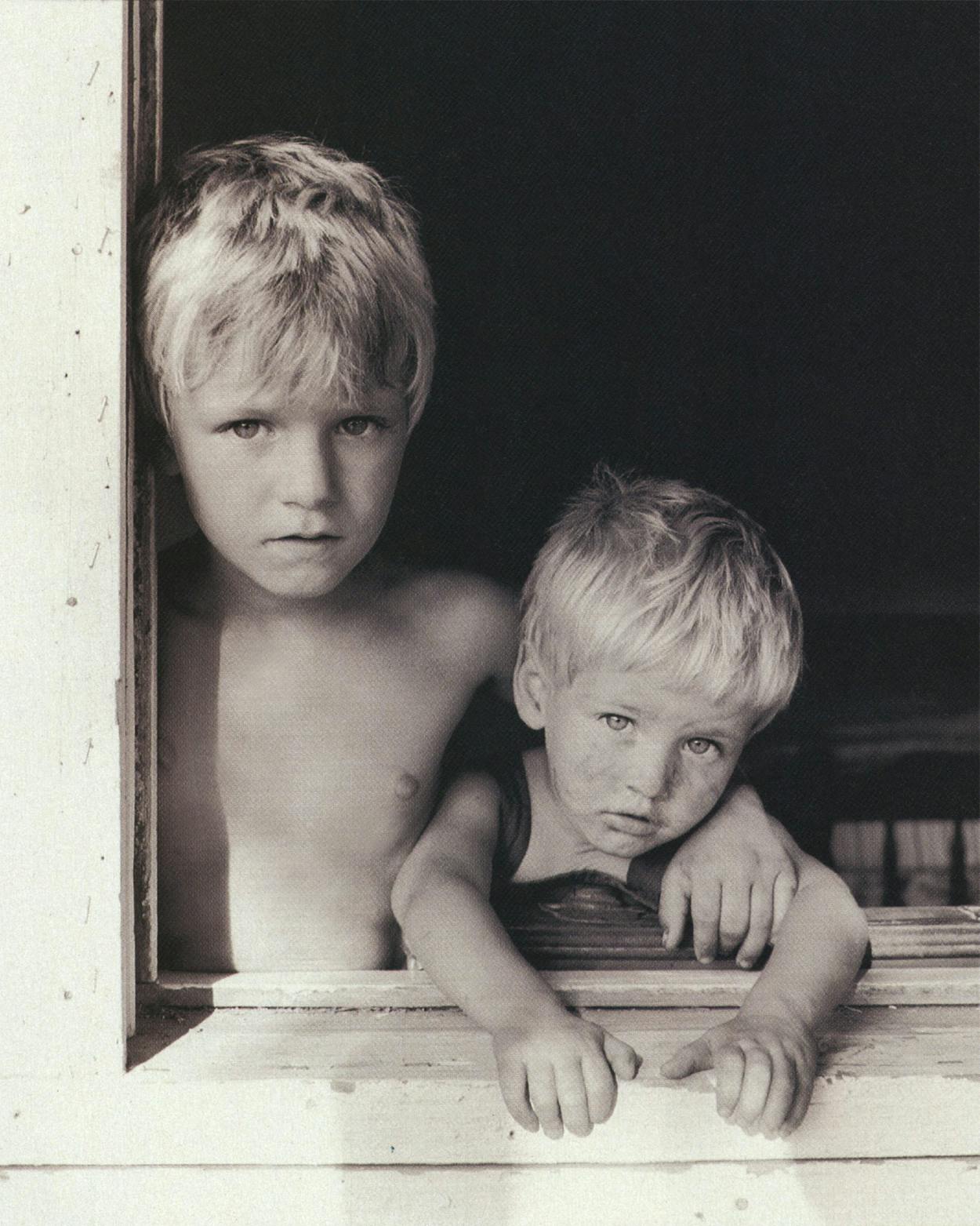

Keith Carter, like Katherine Anne Porter, has the gift of taking the things we have seen all our lives—a watermelon stand, a black country church, a graveyard, a clothesline with chickens underneath, a country store—and giving them another dimension, a beauty that you can’t easily be rid of.

Some of the names that grace these towns—Omen, Ding Dong, Hoard, Art, Sweet Home, Circle Back, Rosebud, Noonday, Poetry, Fairy, Elysian Fields, Grit, Dime Box, Pluck, Sublime, Industry, Cost, Bessmay, Call, Uncertain, Fair Play, Looneyville—no writer would dare invent for his fictional towns. There is often much wit and playfulness in what Keith Carter chooses to show us of many of the places.

Do I have favorites? I look often at Climax, where we see a background of overpowering trees, and in front of the trees are small tombstones leaning in all directions. And the man in Air who looks like a Marlboro Man gone to seed, sad beyond belief. And I’m intrigued by the irony implied by the field with bales of hay stacked upon each other, and on the hay, facing us, is a large paper target of a deer, riddled with holes, in Mount Calm. And Circle Back intrigues me, with its stretch of huge pipe held up by metal trestles, one end pointing toward the sky, the opposite end on the ground and disappearing beyond the camera’s range.

And so it goes: houses, clouds, people, buildings, fields—things we have seen countless times and paid no attention to in all the Texas towns we’ve ever known or been in. And here comes Keith Carter, with his lack of sentimentality, with not a trace of condescension or superiority, but with humor and a deep and honest respect and affection for what he has observed, with his ever-discerning eye, a poet’s eye really, and makes us see all these familiar things—fresh. He has fixed all of this with an exactness that not only defies time but also seems to welcome it in the way that Walker Evans did with his photographs for Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—photographs that seem as powerful and meaningful today as they did all those years ago.

It has been many months now since I first saw Keith Carter’s photographs. I have had my own copies of them with me in New York City for most of that time. Barely a day has passed that I have not looked at them, and they are as moving to me now as when I first saw them in Galveston. They bring vividly to me here in the midst of this city, so far away and so different from the world of the pictures, a happy reminder of that Texas so little known in these parts, a Texas unlike the crude stereotypes so often paraded before us here in the Northeast.

I hope the towns and places in these photographs will be with us for a long time, giving us some sense of what our past was like. But even if all of that vanishes, we’re fortunate indeed to have this sensitive and powerful evocation as a record of what these towns, and the life in these towns, were like.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics