This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Five years ago I had saved enough money to finance a trip to Paris over New Year’s. So on one cold, blustery day, I found myself in a sidewalk cafe, lost in a reverie brought on by black coffee, cigarette smoke, and the magnificent newness of it all. But then, through some instinct, I sensed a familiar presence, and I turned to see a stranger I knew all too well.

She was beautiful. Tall and long-legged, she had blue eyes, high and mighty cheekbones, and a cascade of shimmering blond hair pulled up in a ponytail. Her legs were crossed ostentatiously, and her fur coat fanned behind her like a prop in a display. She had dressed like an honors student in French fashion, having paired an Hermès scarf with Chanel earrings, but she had managed to be scrupulous and excessive at once: The accessories were boldly signatured, the jewelry was oversized, and the pullover sweater was a pretty but very bright shade of green. The two men with her—also excruciatingly turned out—spent their time talking business as if she weren’t there. I had a suspicion, and I couldn’t stop myself. “Say,” I said, leaning toward them, “where are y’all from?”

The trio eyed me coolly before one of the men offered the answer I would have staked the rest of my trip on. “Dallas,” he said tersely and then went back to his conversation.

Well, they weren’t very hard to figure. I had been living in Dallas, so I was well acquainted with the type of flawless females who were ubiquitous there. Thousands of miles from home, this woman had the classic look. To her all-American beauty she had added meticulous grooming (spare-no-expense division) while fiercely refusing to kowtow to understatement. This ferocity extended to her character as well; an unmistakable antsiness to her bearing said that she wanted to be out having fun, not stuck in some smoky cafe listening to two stiffs talking investments. To me it was clear: The confounding blue-eyed, blond-haired beauty, the attitude, along with the flouncy fur and the fancy French earrings might as well have been a sandwich sign that read “Big D—That’s Me!”

Then, too, there was a last clue: my own reaction. Up to that point, I had been perfectly happy to wander about the global fashion capital with clean hair and no makeup, wearing a wool coat, a heavy black sweater, and Nikes. But from the moment I saw that woman, I felt my anonymity ebbing and my ambivalence rising. I could appreciate her particular style because it reminded me of home; but because it reminded me of home, I also felt a case of personal dissatisfaction coming on. The crowded cafe faded from my consciousness; there seemed to be just the two of us, and I was back in that time-honored, memory-charged role of second-best—not pretty enough, not well groomed enough, certainly not blond enough.

I had traveled far only to find myself in a very familiar place—back in a wrestling match with the Texas ideal. Maybe the woman lacked a few of the characteristics I had come to associate with the standard Texas beauty—a welcoming whiskey laugh, for instance, might have shaved a few seconds off my response time. Still, I knew her when I saw her: too made-up to be Californian or Midwestern, too careful about getting it right to be a New Yorker, too restless and hardy to be a Southern belle. She had haunted me all my life; three thousand miles away, I might just as well have stayed home.

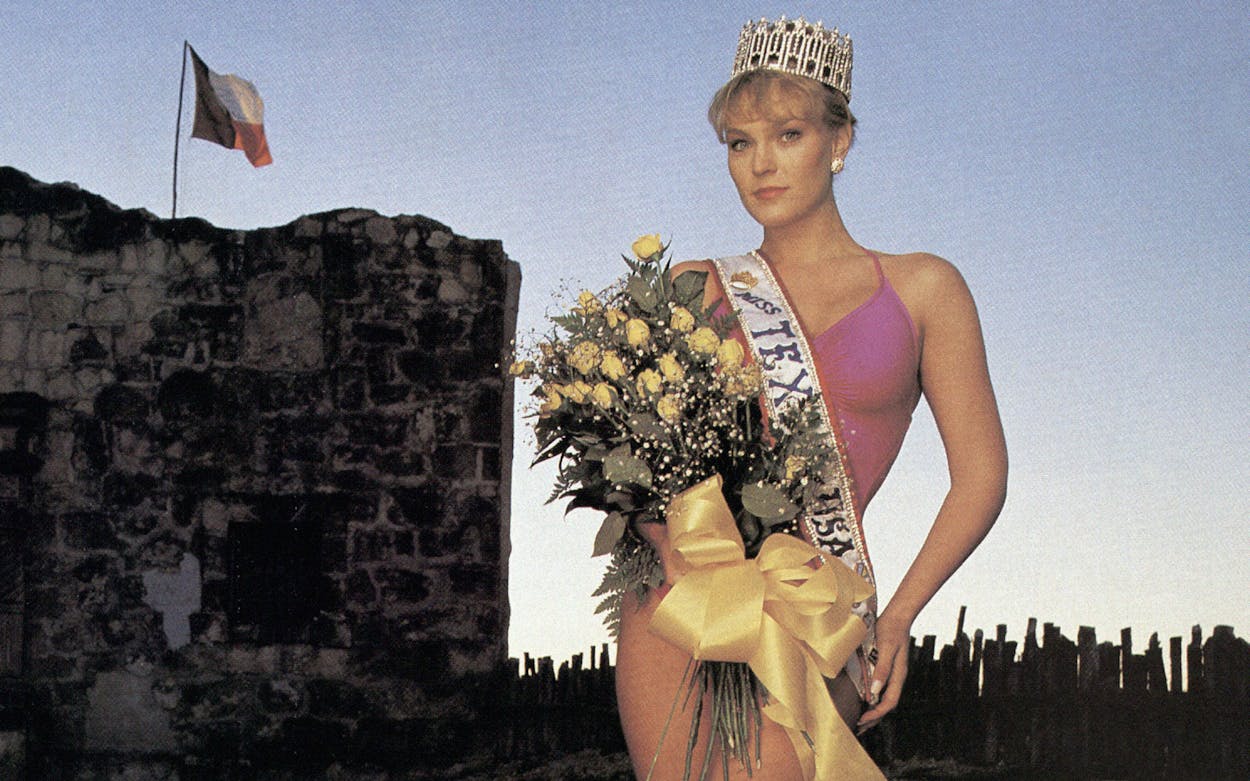

Feminine beauty and Texas have always been powerfully connected in my mind. I grew up hearing that Texas had the country’s most beautiful women, and if I doubted it, all I had to do was look around at the seemingly endless parade of beauty queens (Phyllis George, Christy Fichtner), famous models (Suzy Parker, Kelly Emberg, Jerry Hall), Playboy playmates (Debra Jo Fondren, Julie McCullough), and movie and television stars (Sissy Spacek, Farrah Fawcett, Jaclyn Smith). The most cursory reading of newspapers and magazines inevitably turns up more evidence. During the last few months of 1989, for instance, Town and Country magazine ran a story on the Texas woman in its beauty and health section (“Her exuberance and flamboyant imagination are rivaled only by Spielberg’s”), and a debate raged in the Houston Post over the differences between Houston and Dallas women (“Dallas women are flashy, Houston women are flashier”). The Chicago Tribune published a moony memoir called I WISH THEY ALL COULD BE LONE STAR GALS, which began with a tribute to an Amarillo waitress and ended with an admiring anecdote about Dallas model Jan Strimple, who kept her cool when a leopard got grumpy at a fashion show.

“It’s not a myth,” Manhattan modeling mogul Eileen Ford said when I told her that all my life I had heard that the country’s most beautiful women came from Texas. Ford, too, is a true believer. Not only are Texas women beautiful, she told me, but they have great energy and great enthusiasm. “You have to ask yourself who has won the most beauty contests,” she posited in a burst of adopted regional pride. “In a lot of places you see a lot of pudgy people, a lot of pale people. I’ve never once found a good model from Pittsburgh.”

Listening to her, I felt that old ambivalence reappear. As a victim of the fabled Texas inferiority complex, I was delighted when anyone had anything nice to say about my home state; at the same time, however, I felt like a phony. It wasn’t me Ford was talking about, after all, but a stereotype I had spent my life struggling with. I was dark and bookish. Jerry Hall, Lynn Wyatt, and the rest were, to me, less a source of enormous pride than a source of enormous pressure. They were the daunting, taunting ideal.

To some extent, I had inherited my attitude. Every woman in my family has measured herself against some notion of Texas beauty. My grandmother—tall, dark-haired, with a mischievous light in her hazel eyes—had it easy. She came to Texas from Ohio in the twenties, when it was enough to be good-looking. I recollect, as a child, the wistful tradesmen who would remember themselves to her when I ran errands downtown. “Were the women in San Antonio more beautiful than they had been in Cincinnati?” I asked my grandmother the other day. “No,” she recalled flatly, with the self-assurance of one whose beauty has never been challenged. Still, she had wasted no time embracing a myth in the making. My grandmother, when traveling out of state with my grandfather on business, did not demur when men would study her face and remark, “They sure do grow ’em pretty down in Texas.”

By my mother’s time, the definition of “pretty” had become more circumscribed. She remembers proudly that a Texas coed appeared on the cover of Life in 1947, but I can hear just a hint of resentment when she recalls that the cover girl had an upturned nose, gorgeous legs prominently displayed, and long blond hair billowing in the breeze.

Beauty was problematic for me too. Since, like most of the women who live in Texas, I did not resemble the typical Texas beauty, I felt that odd mixture of appreciation and envy. With some defensiveness, I tried to assign her a spot in the lineup alongside other Texas stereotypes I had trouble making peace with. That was easy enough when I lived out of state, but when I came back to Texas thirteen years ago, the ideal was still here, unchanged and resolutely refusing the role I had assigned her. We stared at each other across a great philosophical divide of regionalism and feminism; still, I was drawn to her more than I cared to admit, more than I could understand. Whenever I saw her in my mind’s eye, I saw her smiling broadly, patiently, and I read in her gaze a message that said if I was going to stay here, we would have to find a way to get along.

People have invented many theories to explain the abundance of beautiful women in Texas, and most of them are fanciful and farfetched. “It comes from competing with the sun,” the former editor of a Dallas fashion magazine suggested. Some aesthetes cite the purity of the gene pool—a preponderance of Anglo-Saxon bloodlines was noted with great delicacy by one retailer. But Kim Dawson, the owner of the state’s premier modeling agency, praised Texas’ vast cultural melting pot. “Here you have English, Irish, Mexican—a blending,” she offered comfortingly. Commerce explains the profusion in Dallas at least, with the apparel and airline businesses creating an understandable supply-and-demand situation.

Beauty was, of course, a much rarer commodity in the early days of the state. Among the first immigrants, women were scarce, and pretty women scarcer; those who did come found, like the men before them, a hard place with little to satisfy the eye. “Nothing new but high winds and dry weather,” Mary Ann Peebles wrote in her diary in 1854. Texans’ tendency to mythologize beauty, however, is detectable early on in the face of poor Susannah Dickinson. It wasn’t enough that she should escape the Alamo and endure poverty and prostitution for her trouble. Illustrators gradually converted the heavyset, rather coarse-featured woman into a slim, delicate beauty.

When the oil prosperity began in the twenties, however, no such fantasy was needed. In those years the Cactus, the University of Texas’ annual, overflowed with honors for beautiful coeds. No doubt many yearbooks across the country did the same, but the Cactus was determined to show off the beauty of Texas women—pages and pages of them. The lovelies were often chosen by celebrities like theatrical producer Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., and Mae West.

But one period in the history of Texas beauty stands indisputably as the source of the myth. The year was 1936; Dallas was presenting the Texas Centennial while Amon Carter, annoyed that his hometown had lost out, hired showman Billy Rose for the confounding sum of $1,000 a day to put on a competing extravaganza in Fort Worth. What the two shows had in common were pretty women—lots of them. Those were Depression years, and young women had been drawn to North Texas cities in search of work. In Dallas they found photographer Bill Langley waiting. Hinting at jobs with New York modeling agencies and Hollywood roles, he put these women to work touting virtually every Centennial exhibition. Christening his beautiful bevies Rangerettes, Langley photographed them with Longhorns and airplanes; he shot them riding Brahman bulls, petting chicks, holding bullfrogs by their hind legs, and playing checkers with baby turtles. He put them in ten-gallon hats and chaps and had them greet everyone from meat-packers to governors to sports heroes to Navajo chiefs. The women he employed were not the long, tall Texas beauties of today’s ideal. They had the fresh, round faces and eager smiles of small-town girls.

Not so in Fort Worth, where impresario Rose had been thinking along Langley’s lines. According to the Dallas Morning News, Rose walked down the streets of Dallas and Fort Worth and “got the notion that Texas girls were prettier, fresher, and more vital than those of any other state, territory, or dependency.” The women he favored, however, were flashy, long-legged show-girl types who bolstered his motto, “Dallas for education, Fort Worth for entertainment.” For two years, both men exercised their creative mandates, and the result was two years of unrelenting hype for the beauty of Texas women.

From that point on, local beauties had only to sit back and read their notices. Gorgeous girls became a standard Texas brag inscribed on souvenir maps of the forties. Travel writers, reporting on Texas as if it were an emerging nation, seemed unable to complete their accounts without remarking on the vast numbers of good-looking women. In The Super-Americans, published in 1961, John Bainbridge feigned skepticism but quoted Paul Gallico (“The men are taller, tougher, handsomer, fightin’er than most. The girls are prettier, slimmer, more sparkling”) and the overzealous Robert Ruark (“Texas women grow taller and stand straighter and their lips are redder and their eyes are brighter than any other women’s in the world. Their hair piles higher and their legs sprout slimmer and their sweaters stick out farther”). Ultimately Bainbridge came around. “No matter how long his stay,” he wrote, “the visitor will probably never be able to decide whether the prettiest women in America can be found in Texas, as Oleg Cassini says, or at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street in New York, as Cary Grant says.”

The inevitable occurred in 1966, when Playboy ran its first pictorial on Texas women. The cover girl wore a sheriff’s star and holster over her tight black dress, while inside the magazine, a long-haired blond lab technician named Carol Lee Roberts posed nude atop an Appaloosa, overlooking the plains. Quantity and quality awaited the Playboy traveler: “The Houston career girl,” the story noted, was “a confirmed night owl who spends her working day at just about anything from reporting for the Houston Chronicle to . . . running a cybernetics section at nearby NASA.” The issue was a best-seller.

Texans caught on fast. They could treat feminine beauty like any natural resource, exploiting it for maximum potential. That worked for Trammell Crow when he recruited Kim Dawson to start a modeling agency for his Apparel Mart; that worked for Southwest Airlines’ “Love” campaign; and that worked for a TV movie starring the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders (it had the highest ratings of any made-for-television movie in 1979). There was plenty for everybody; outsiders who may have been put off by Texas money or Texas manners softened when confronted with so many pretty faces. Even dress designers, happy to feast on the vast and untapped Texas market, took their cues from Oleg Cassini and to this day are more than willing to carry the word. “Adolfo was just saying yesterday,” a Neiman’s employee said to me, “that Texas has the most beautiful women he’s ever seen.” Whether that was true or not, the desire to make it true flourished; everyone saw the beauty of Texas women not as a myth but as a reality.

It is impossible to look at the Texas ideal without looking at the macho culture that had a major hand in creating it. “A man who doesn’t admire a good steer, a good horse, and a pretty woman—well, something is wrong with that man’s head,” cattle king W. T. Waggoner liked to say. (Waggoner’s daughter, Electra, it might be noted, set the standard for world-class shopaholics.) Connoisseurship thrived here as everywhere—my favorite story is the one about the famous Texan who expected his lover to turn her face to the left during sex. “That’s your good side,” he explained.

Still, there is much to like in the women these men admired. A distinct personality emerged. Though Stanley Marcus’ adoration of Grace Kelly put a princesslike stamp on one segment of Dallas beauty forever, he was unable to impose his taste statewide. Kelly had the right looks, but the average Texan could not warm up to her remote, aristocratic bearing. Books like Prominent Women of Texas, published in 1896, give Southern belles and society women their due, but clearly, Texans’ hearts remained with the cowgirl, who knew how to make her way in a man’s world, who understood and had shared his struggle to survive. There was, for instance, Anastasie Lockhart, heroine of the novel North of 36, who, according to author Sandra L. Myres’ essay “Cowboys and Southern Belles,” could “ride, rope, and herd cattle with the best of her men.” She was also beautiful—in the novel she is described as “rarely, astonishingly, confusingly beautiful.” There was also the real-life Kitty Le Roy, who, according to Dee Brown in The Gentle Tamers, mastered jig dancing in Dallas and then took off for the Black Hills. “Kitty Le Roy was what a real man would call a starry beauty,” one reporter wrote. “Her brown hair was thick and curling, she had five husbands and seven revolvers, a dozen bowie knives and always went armed to the teeth, which latter were like pearls set in coral.” Le Roy married her first husband because he allowed her to shoot an apple off his head while she rode by on horseback.

Such earthiness was immortalized—and disseminated—in wild West shows, where it was dusted off and polished until it shone; glamour became part of the ideal. The great beauty of the second half of the nineteenth century was Adah Isaacs Menken of East Texas. Hefty by today’s standards, she began her career touring dance halls, performing in Mazeppa on a real horse while wearing nothing more than a flesh-colored body stocking. Everybody liked Menken; after conquering the West, she headed for Europe, where she supposedly ended up marrying German royalty and became a confidante of Dickens and Flaubert.

But the stereotype owes an even larger debt to Menken’s spiritual descendant, Texas Guinan. Raised a lady on a ranch near Waco, she went from dainty Hollins School in Virginia to the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch Circus, where she starred as a cowgirl and bareback rider. She became a star of silent westerns and went on to become the toast of Broadway and the queen of New York’s nightclubs. The public fell for her whiskey voice and wisecracks—“Hello, sucker” was her contribution to the lexicon—and, of course, her looks. “Golden haired, buxom, she dripped mascara and flamed with cosmetics” was how one writer described her.

Guinan remains the spiritual role model for everyone from Barbara Jane Bookman, the heroine of Dan Jenkins’ Semi-Tough, to Jerry Hall to any Southwest Airlines flight attendant—women who are good-looking, yes, but who are also fun to be with. Lamar Muse may have invited Sophia Loren to apply for a job as Southwest’s first stewardess, but what he settled for was a woman who was Hollywood on the outside (note, please, the enthusiasm for theatrical eye shadow and hair) and a good ol’ girl at heart. “We just wanted the all-American girl with a great personality. As they’d walk down the aisle they wouldn’t be stewardesses,” he says, “they’d be hostesses. Everybody on the plane would be our guest.”

Even that wish has its history in Texans’ own version of the Madonna-whore complex, in the cowboy’s inability to reconcile the lady he idolized with the hooker who made him feel at ease. The Texas stereotype is accessible, but she can draw the line when she has to. Farrah may have dressed in skimpy clothes, but she never went anywhere close to all the way on Charlie’s Angels. (Her roles nowadays—setting fire to an abusive husband’s bed, torturing a rapist, murdering children—almost seem like a bizarre form of psychic revenge.) The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders have had a little more trouble with the concept. They gained national prominence like typical good-time Texas girls—a member of the squad winked at a television camera during the Super Bowl in Miami in 1976. Since then, they have continued to profit extravagantly from their sexuality, but they also hunt down and morally maraud anyone who tries to push them farther than they want to go—whether it’s the producers of the pornographic Debbie Does Dallas or team owner Jerry Jones. When group leader Tina Miller, 24, resigned last fall upon learning that she might have to fraternize with players, appear in beer commercials, and wear spandex shorts, she could have been any proud woman trying to keep her head high in the wild, wild West. “We had so many rules to uphold,” she explained, “and that’s what made us classy and respectable.”

Ask for a definition of Texas beauty, and many will respond as one Arkansas woman did recently: “Big hay-er,” she said to me with finality. Big Hair has become such a part of the culture that Tom Davis, a Lubbock-based owner of several beauty salons, even provides visitors with Big Hair tours. “Those Houston hairdressers, they don’t know Big Hair,” he said, leading me into a local cafeteria. Indicating one server whose bouffant was a glorious silvery blue and sat atop her head with a foot-high, foot-wide grandeur that would have made Marie Antoinette jealous, Davis looked pleased. “That is Big Hair,” he said.

Hotly debated and often openly scorned—it’s cheap, it’s flashy, it’s hopelessly out of date, say its detractors—Big Hair, to the uninformed or totally inured, is an enormous amount of hair that has been sprayed, dyed, and permed into a mane that commands attention. Non-Texan Jacqueline Kennedy had it as first lady; Farrah Fawcett and Jaclyn Smith had it on Charlie’s Angels; today you see it on everyone from Lynn Wyatt to Southwest Airlines flight attendants. “This is the problem with the Texas look,” explained Dallas salon owner Paul Neinast. “If a little bit looks good, a whole lot’s better.”

World-class ambitions aside, Big Hair persists. Though he claimed to be beyond Big Hair, Neinast is no stranger to it. In an ultramodern variation, he now weaves the likes of grape ivy, turkey feathers, and birds of paradise into clients’ hair in two-hour ordeals that cost around $200. Houston’s Clay Ellison, a salon owner who assists Lynn Wyatt, accepts responsibility for perpetuating the style but insists that most women need only to slick their hair back and put on red lipstick to look good. “They all want to look like Lynn,” he complains of Houston women, “but Lynn has naturally big hair.”

It is easy to link Big Hair with our affinity for flamboyance; no one would dare argue that audacious adornment is not a constant in the history of Texas’ rich. Maud Young, for instance, reported on “hair monstrosities” in her memoir of late-nineteenth-century Houston: “They were immense pone-like affairs covered with nets and easily pinned over the wearer’s tightly-twisted locks. This style of hair dressing was superseded by the really beautiful ‘waterfall’ which was accomplished by rolling . . . in the back with a cascade of curls often reaching to the waist. Then came the truly regal looking coronet braid, and later the French twist, figure eight, Psyche knot, Pompadour and such.” In the fifties the story was the same. A former resident of Midland told me of the astonishment that greeted the arrival of George Bush and his pals. “Those women wore Buster Brown haircuts, madras shorts, and oxfords,” she told me. “Everyone else would be plucked and dyed to the teeth just to play bridge.”

Texas’ enthusiasm for big beauty has never been limited to the big rich, though. Mary Kay Ash did not become the wealthiest self-made woman in the state by catering solely to clients with money. Texas ranks third nationally in population but second—to California—in the number of beauty salons. Flamboyant beauty is really just the most obvious aspect of another, deeper characteristic: Texans’ obsession with grooming. In many places, beauty and grooming are viewed as separate entities, but that is not the case here. In Texas natural beauty is something of a starting point; like the land itself, it is there to be dominated and tamed into submission.

Reading up on the subject, I’ve come to believe that Texans have never seen a face that they couldn’t enhance. Self-improvement is an obligation. It was big news, for instance, when the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders took personal development courses. THIRD TIME IS CHARM FOR MISS TEXAS, WHO SAYS NEW ATTITUDE WAS CRITICAL was the way an Austin American-Statesman headline cheered the beauty contest winner. It’s part of the Kim Dawson legend that her models were for many years not quite as sleek and sophisticated as their New York counterparts. “Mrs. Dawson admits that a large part of her job is simply convincing people that they look good, and gently suggests they could look better if . . . ” the Dallas Morning News noted. Added Dawson: “I have a gift for making people feel better about themselves. I can remember working harder with the not-so-pretty girls, and they were so grateful they’d follow me home at night.” In this context Big Hair looks like just another attempt to bend beauty to the Texas will. One Amarillo woman I know included hair spray instruction in the self-improvement courses she taught at a department store. The truly attractive woman, she believed, should be properly armed against the ravaging West Texas wind.

What outsiders see as excessive narcissism may be just that, but the passion for looking good is also a bow to the politeness, propriety, and nasty niceness that are part of our Southern heritage. (“Tacky” remains one of the most powerful pejoratives in both cultures.) One woman I know recalled that a sorority sister considered taking up a collection to send her to the hairdresser so that she could be a more effective representative. (Attending a national meeting of that group a few years later, she noted that the Texas women were unstoppable. “See that Kappa from William and Mary?” a UT sister sniped. “We’d have that moustache off her in a week.”)

But most important, the well-groomed face is the face we want the world to see. It reveals us as still determined to prove to outsiders that we aren’t hicks, even if the world, at this point, couldn’t care less. Bainbridge noted that “the wives of Texas millionaires, taken together, were not only well dressed but noticeably well dressed. Their clothes are expensive, and they show it.” Salon owner Tom Davis sounded strikingly similar when describing the typical Texas beauty: “She gets out of a limousine. She’s got on the right shoes. She’s got on the right dress. She’s ready.”

The embodiment of such fantasies is Lynn Wyatt, of course, who managed to climb to the top of the social heavens without embarrassing her home state once. Anyone who doubts Wyatt’s primacy in such matters—and who doubts that Texans have outgrown their obsession with competitive dressing—would do well to review news clippings of the fall visit of the Duchess of York to Houston. The coverage, you recall, could not get past Fergie’s shoes, which were out of season. It’s hard not to see the event as some sort of watershed in the history of Texas grooming as, in photo opportunity after photo opportunity, Wyatt seemed to outshine her royal houseguest. (“I ask you—who was the real princess?” sneered one Dallas fashion fanatic.) The eyes of Texas are upon you, the coverage seemed to be saying, and more than a few women seemed to have taken the warning to heart. A few days after Fergie’s visit, I was in the Stanley Korshak store in Dallas when I heard someone speaking softly nearby. I turned to see a modestly dressed middle-aged woman standing in a ray of sunlight, as if she carried a divine message. She was pointing at her shoes, and I realized she was talking to me. “I’m from Florida and I’m sorry,” she said. “I know you Texans don’t like white shoes after Labor Day.”

“Kim got it late,” people in Dallas tell me. “Real late.” This sentiment reveals another historic marker of Texas beauty, the moment in the mid-eighties at which Kim Dawson, her domination of the Dallas modeling business slipping, came to see that her blond, blue-eyed ideal was being challenged by what was euphemistically called an “exotic” look, meaning, of course, minority women. (By then, Southwest Airlines and the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders boasted a respectable number of black and brown faces, but Dawson’s vision of Texas beauty remained so rigid that Jerry Hall was considered too tall, and she was directed out of state.) When I went to interview Dawson on the subject, however, all memories of the nightmare that could have been had been banished in an irrepressible show of good cheer and pragmatism. “Whatever looks good in front of the camera” was her definition of the Texas look. “The face is the same all over the world now.”

As proof, we paged through Dawson’s book, and though blue-eyed, long-haired blondes may have prevailed, they didn’t dominate the way they used to. Then Dawson invited a ravishing young woman into her office. Indicating her fine points like someone displaying a prize in a game show, Dawson stressed the model’s small bones, her huge, almond-shaped hazel eyes, jet-black hair, and coffee-colored skin. “That’s the ‘different’ look,” she whispered after the model had been excused.

Just how pervasive that different look has become was made clear to me last November, when I was asked to judge a beauty contest. This was not the big time: The Miss Texas Glamour Girl Pageant was held in a ballroom at a north Houston Marriott hotel. I had been pressed into service when I introduced myself to one of the sponsors, a beauty queen turned beautician. “Great,” she said, learning I worked for a magazine, “you can be a judge.”

So for a few hours on a cold, rainy Sunday I sat at a long table between two women who were far more knowledgeable than I in such matters. One had been a Miss Go Texan pageant finalist; the other, the MC announced, “had participated in the Snow Queen pageant and had modeled in Kingwood.” I had expected to feel like a traitor to the feminist cause—or maybe even to enjoy being the one who set the standard instead of the one who tried to live with it—but I realized fairly quickly that small-time beauty contests are no place for sexual politics or precious ironies. It’s grim work. “You only make one person happy” is the standard lament of beauty contest judges, and seeing the desperation on the faces of the girls and their mothers, some of whom, it was clear, had spent every penny on the contest, was enough to banish any old ghosts and secret agendas.

I judged the two- to seven-year-olds and the preteens without much trouble. Then the teenage girls appeared on the portable stage. Before me was a sampling of the different types of beauty that modern Texas was currently accommodating. There was a handsome Hispanic girl named Carla, a striking Vietnamese girl named Thuy, and two familiar faces: a pair of tall, blond girls who had been practicing their pivots and turns with drill-team precision before the pageant began. Their names, in truth and in fact, were Heather and Ashley. When I commented on the ethnic variety to one of the judges, she nodded, took a pull on her cigarette, and told me the kinds of stories that have become standard beauty contest lore: about competitors who, not so long ago, tried to pressure minorities out of beauty contests, and about sabotage techniques, like pouring makeup on a contestant’s evening gown.

Seeing no such trials in evidence, I faced my task as honestly as possible. I looked at the other girls, and then I looked at Ashley, with her crinkly, winning smile and her gold bangs tamed into a shimmery, static waterfall. I longed for there to be a dark-haired beauty to surpass her, but there was none. I did my job, marking Ashley on my ballot as my choice for Miss Texas Glamour Girl. At peace, I listened as the MC announced that Thuy was the winner of the pageant.

Well, I thought, Texas had changed and so had the standards—I was the one who had lagged behind. This sentiment, though noble, was tempered by one small problem. This particular contest was rigged. The MC had announced the winner without picking up our ballots. “Don’t let the parents see your tally sheets,” the judge to my left whispered wearily. What had happened was this: The contest was designed as the culmination of a series of beauty lessons sponsored by a local modeling school. But when there hadn’t been enough contestants from the classes to make a contest, the sponsor solicited more entries by placing an ad in the paper. When Thuy’s father learned that some of the women had entered the contest without paying the $75 entrance fee, he demanded that they be ejected from the pageant. As a compromise, Thuy was chosen the winner of her division.

I talked to Thuy later, avoiding the topic of her somewhat clouded victory. When I was a girl growing up in Texas, I told her, girls like Ashley were the only ones considered beautiful. Thuy, who wants to be an engineer, found this notion amusing. “Yes,” she said, giggling, “but now they want something different.” I was not sure I believed Thuy, and then I realized that she was not so different-looking after all. She was tall and confident, and the day I saw her she was fashionably dressed in a flashy silk suit with big shoulders. She had permed and moussed her hair into an unabashed mass of jet-black curls, which she arranged and rearranged before a mirror with the concentration and precision of a brain surgeon.

Thuy’s parents, Vietnamese refugees, were all for this transformation. Her father bought into the traditional Texas look the minute he shelled out $75 for Thuy’s entrance fee, and he proved his loyalty to it when he threatened to scuttle the whole contest unless the rules were adjusted to his particular sense of fair play. He was as eager to embrace and perpetuate the local standards as any homegrown Texas dad. His eyes had accommodated, he had found a new way of seeing; but in pursuing the ideal, he had, like the rest of us, shown how much he wanted to belong.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Longreads