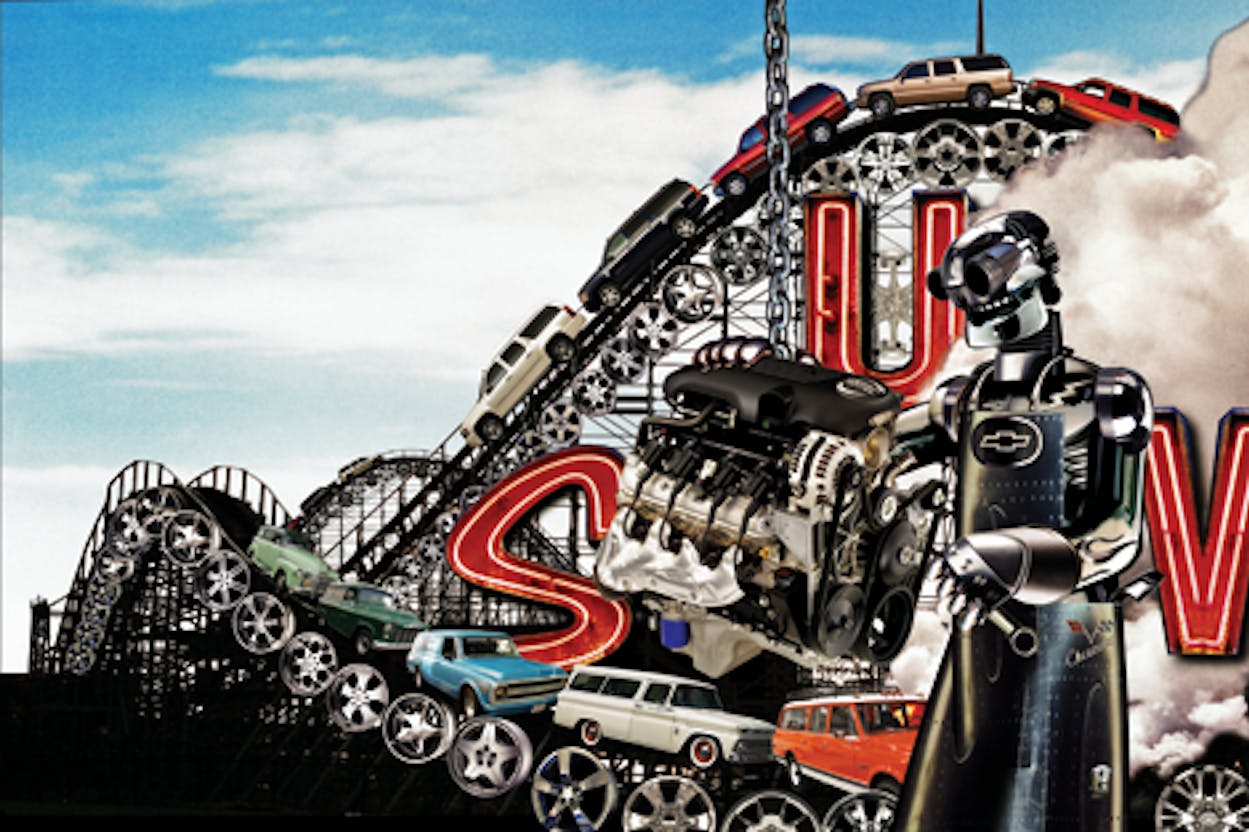

The place is a miracle of contrivance, a Rube Goldberg–esque wonder of moving platforms, roller-coaster conveyors, pirouetting robots, and banks of electronic controls that Henry Ford could never have imagined. I am standing in the whirring, clanking heart of General Motors’ Arlington assembly plant, a 3.75-million-square-foot facility whose sole job is to make full-sized sport-utility vehicles—Chevrolet Suburbans and Tahoes, GMC Yukons, and Cadillac Escalades. Enormous and immaculate, they advance down the assembly line at the pace of a wedding procession. They come in colors like Black Ice, Sheer Silver, and Red Jewel. Thirty-five years ago this plant produced the Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme, at the time the best-selling car in America. Today’s glittering monsters—with hybrid battery power systems, fuel-switching engines, cylinder deactivation, and rearview cameras—make the Cutlass Supreme look like something from the dawn of the Industrial Age.

The plant has two 10-hour shifts and recently increased production to more than a thousand vehicles a day. It employs 2,400 people, who earn $29 an hour, and many put in 60 hours a week, logging more overtime than workers can remember. The wages reflect the plant’s profitability. GM earns as much as $10,000 on every SUV sold, seven times the profit margin for ordinary passenger vehicles. Business is very good.

For those readers who are scratching their heads: You are not in a time warp; this is not supposed to be happening. In the recession-shocked year of 2010, workers were not expected to be logging overtime to produce gigantic, expensive, gas-chugging SUVs. In June 2009 GM declared bankruptcy, having lost $88 billion in the previous five years. The company survived only because of a massive government rescue and huge infusions of capital and loans. Along the way it shut down fourteen plants, displaced 20,000 workers, and announced plans to end relationships with 1,300 dealerships across the country.

Moreover, these SUVs, which had once redefined the American car industry, had also suffered a devastating fall from grace. In 2003 sales of full-sized SUVs peaked at 773,000; last year that number nose-dived to a mere 217,098. Even more disastrous, their decline in sales was nearly twice as bad as that of cars and light trucks. But consumers didn’t abandon big SUVs simply because of their price tags, which can run more than $40,000. The vehicles had become cultural pariahs as well. Suddenly the behemoths seemed to be responsible for everything that was wrong with America: our outsized lust for material wealth, our dependence on foreign oil, our abuse of the environment, our disregard for safety, and even our involvement in the war in Iraq. If any product seemed marked for death in this imploding empire, it was the full-sized SUV. Many people thought the hulking vehicles would be left to die—along with entire brands, like Oldsmobile, Pontiac, and Saturn. And as the Suburban and Tahoe disappeared, it seemed that GM would vanish as well.

What happened instead will provide MBA students with case studies for years to come. The company emerged from bankruptcy last year and then paid off a $6.7 billion government loan in April. It has returned to the black, and it is planning a stock offering that will reduce the government’s ownership stake, which is currently 61 percent. After years of making dreary, second-rate cars, GM’s Cadillacs, Buicks, and Chevrolets are once again competitive with products from Japanese companies like Toyota, which is still reeling from the worst safety scandal in its history. Last year workers feared that the Arlington plant might close its doors forever. Now it looks more like a symbol of GM’s resurgence.

“There was a lot of worry,” said plant manager Paul Graham, who started his career building Suburbans 29 years ago in Flint, Michigan. “We are not out of the woods yet, but we’re back to full production. I think we’re getting our confidence back.” As part of its cutbacks, GM mothballed two facilities outside Texas that made large SUVs. But the Arlington plant survived, making it the only place in the world that builds Suburbans, Tahoes, Yukons, and Escalades. If it once appeared that these venerable brands, which had become so closely linked to our culture and our way of life, might vanish, Arlington has emerged as the site of the Suburban’s last stand. That is fitting, given that Texas not only remains the largest market for full-sized SUVs but also embraced them long before anyone else. By adopting the old Suburban in the seventies and eighties, Texas launched one of the most successful product categories of the past century.

It’s two o’clock on a beautiful Tuesday afternoon. I am cruising from Austin to Dallas along Interstate 35. The traffic is light, my radio is on, and the Blackland Prairie is sliding by my window in a blur of greens and browns. It would be just another routine trip, one that I’ve driven more than a hundred times, except for a single conspicuous fact: I own the road. Encased in 5,600 pounds of steel, leather, rubber, and more high-tech gadgetry than you can shake a stability control system at, I am sitting behind the wheel of a $55,000 Chevrolet Tahoe with a six-liter Vortec V-8 engine that cranks out 332 horsepower and 367 pound-feet of torque and can accelerate from 0 to 60 in about eight seconds. Sitting high above the poor saps in their puny sedans, whom I look down upon with pity and compassion as I pass them, I finally understand the phrase “high, wide, and handsome.”

You have probably guessed that I don’t drive a large SUV. This one is a brand-new loaner from GM. I have owned a series of Ford Explorers for the past eighteen years, but they lag far behind the Tahoe in all the categories that count: size, power, and a certain aura of invincibility that guarantees no one is going to mess with you. When I drive my daughter’s Honda Civic, I am constantly amazed at the number of thirtysomething guys with facial hair driving Ford F-150s who will actually bully the little car by roaring up behind me and showing their displeasure at my size, speed, and national heritage. But nobody disses a Tahoe.

Texans understand these feelings of power and security deep in the cortex of our brains, and that is why we buy more of these vehicles than people in any other state: one out of every five large SUVs and approximately 22 percent of the Tahoes sold in America. To live in Texas is to understand why there is a market for them. They manage to do what no other vehicle does, which is to be a status symbol for both the middle and upper classes. They are both practical and showy. Texans love them irrationally and exuberantly and in spite of shortcomings, from price to fuel efficiency to handling. Take Bruce Quernemoen, for example, a sixty-year-old executive from McKinney who is on his fourth Tahoe, a vehicle that is nearly identical to a Suburban, except that, at 16 feet 10 inches, it is 20 inches shorter. He bought his first one after his wife complained that she no longer felt safe on the highway. “If I need to pass, I want to be able to pass,” said Quernemoen, who likes to load up his grandchildren and take them for rides. “This Tahoe is like a sports car when you want to pass. It just takes off.”

Though Quernemoen admits that he hated to pay nearly $70 to fill up his gas tank two years ago—and that he flirted traitorously with the idea of buying a Chevy Traverse crossover—he is sticking with his brand. The extra five miles per gallon were not worth it, he said. So last year he bought another Tahoe, for just under $50,000. He took his obsession even further: He traveled to Arlington to videotape the car’s assembly and proudly posted it on YouTube.

These obsessions know no age limits. “I’ve wanted a Tahoe ever since I was fifteen,” said Jennifer Euwer, a single, 24-year-old labor-and-delivery nurse from Galveston. “That’s what everyone wanted when I was that age.” Euwer liked the styling, but mainly she enjoyed the sheer size of the thing. Her mother drove a Suburban, and her father owned a full-sized pickup. They also wanted her to drive something big, out of concern for her safety. Her first car was a used Ford Explorer, followed by a Jeep Liberty. But she found them confining and inferior. “I always knew that the second I could afford a Tahoe, that is what I was going to get,” she said. Last year she bought a loaded gray Tahoe for $42,000, putting $9,500 down and paying $658 a month. Now she uses it to take her friends and her dog to the beach or to go bowling. When asked if owning such a megaride makes her stand out among her friends, she replied, “When the majority of my friends got jobs, they bought Tahoes too. But I’m the only one who paid for it myself.”

In August 1986 TEXAS MONTHLY ran a cover story about the Suburban titled “The National Car of Texas.” Written by Paul Burka, it celebrated what would turn out to be a historic shift in the American car market. Texas had adopted the unlikeliest of vehicles, an ungainly-looking passenger wagon that had been bolted onto the frame of GM’s basic pickup. The result was an enormous, four-door, trucklike contraption that could seat nine people and tow a 25-foot boat or a three-horse trailer without breaking a sweat. The Suburban inhaled gasoline, averaging between ten and twelve miles per gallon in the city, and had, in Burka’s words, “a turning radius that wouldn’t fit in the Astrodome.” Texans, who routinely traveled long distances in their cars and whose culture was still deeply rooted in the practical realities of farm and ranch life, loved them. Houston and Dallas became the biggest markets in the nation for the cars, with San Antonio and Fort Worth not far behind.

While the rest of the country insisted on seeing the Suburban as a sort of juiced-up delivery vehicle, Texans embraced it as an über-station wagon. It transcended mere popularity and became a status symbol, driven by famous Texans, including Treasury Secretary James Baker, Senator Lloyd Bentsen, Southwest Airlines CEO Herb Kelleher, and Hall of Fame quarterback Roger Staubach. At the Capitol the vehicles were known as “lobby wagons,” because lobbyists liked to load them up with legislators and go to lunch. Society loved them too. In Dallas they jammed the pick-up lanes at the Hockaday School and St. Mark’s School of Texas, and they became the preferred vehicle of the Houston Junior League.

Yet despite its cachet, the Suburban was not expensive. The 1985 model Burka had bought cost $15,150. (He priced a Chrysler minivan that same year at $13,300.) Nor did the car change from year to year to keep up with automotive fashion. The 1986 Suburban—or 1987 or 1988, for that matter—was nearly identical to the 1973 model, the last one to undergo significant changes. And it was impossible to load one up with the options that later became so common; “fully loaded” basically meant getting a slightly larger engine and a two-tone paint job.

It was remarkable too that the car had survived at all, considering its initial design. Now celebrating its seventy-fifth year, the Chevrolet Suburban was first introduced in 1935, making it the longest continuously produced vehicle model in the United States. To create it, engineers incorporated the hood, engine, fenders, and underbody of a pickup and replaced the cab and bed with a long passenger compartment. Originally it had only two doors, not counting the tailgate. Though it was marketed as a vehicle that could be taken on camping trips—a 1935 ad shows a happy family camped along a river with a tent, boat, and Suburban, with snow-covered mountains in the background—its two-door configuration made it hard to get into and out of. It found its main use as a service and delivery vehicle, its rear seating removed and its side windows filled in behind the front seats.

It survived not because ordinary people wanted it but because it was useful for businesses. Some of its principal buyers were funeral homes. Undertakers had discovered that the rear section of a Suburban was exactly the right length for transporting the dead. Thus the cars became popular as “first call” vehicles that picked up corpses at homes or hospitals and transported them to funeral parlors. While converted limousines remained the cars of choice as hearses, Suburbans carried flowers and chairs and coffins and generally did the dirty work of the business. As New York Times reporter Keith Bradsher wrote in his book High and Mighty: SUVs—The World’s Most Dangerous Vehicles and How They Got That Way, “The height of the Suburban’s rear cargo floor partly reflects an early effort by GM engineers to find a comfortable height for loading and unloading the dead.”

Though the vehicles that Quernemoen and Euwer bought in 2009 are direct descendants of Burka’s 1985 model, they seem to be entirely different species. Burka’s car was cheap, primitive, and ugly compared with today’s Suburbans and Tahoes, which are luxury vehicles that brim with leather and chrome and twenty-inch wheels and high-output engines. The change occurred during the nineties, a decade when the middle class recalibrated its sense of entitlement. Propelled by the longest economic boom in the nation’s history, Americans decided that, from $400 KitchenAid mixers and granite countertops to large-screen televisions, they simply deserved better than they had had before. Some called it the “luxurification” of America, and the Suburban proved to be a perfect example.

In 1991 Chevy switched its Suburban to an upgraded truck platform, the GMT 400, with its street-friendly suspension. The result was a stunning upgrade for the 1992 model year that featured a long, sleek body with more glass and an updated interior. That year the Suburban was still the only American-made full-sized four-door, four-wheel-drive SUV on the market. The success of the redesign would change all that. In 1995 GM introduced four-door versions of the Chevy Tahoe and the GMC Yukon; the Cadillac Escalade appeared in 1999. All were crafted from the same underpinnings and shared many of the same parts: GM had simply split its old Suburban into four vehicles. It was a brilliant sales strategy. Base prices for the Suburban rose to $18,155 in 1992 and $27,421 in 2000. Yukons and Escalades commanded premiums. Other automakers were quick to follow GM’s lead. Toyota introduced its Lexus LX and Toyota Sequoia; Ford launched its Expedition and Lincoln Navigator. Yet GM still dominated the market, with roughly 60 percent of all large SUV sales, and the Tahoe emerged as its best-seller. Meanwhile the market for midsized SUVs, kick-started by the revolutionary Ford Explorer in 1990, had shifted into high gear too.

In the late nineties and early 2000’s, sales of large SUVs exploded. In 1983 Suburbans and their cousins sold 150,000 units; by 2003 sales hit 773,000. And the market was dominated by Texas, where one in five vehicles were sold. Yet sheer volume was not the only measure of success. Because these vehicles were still, in effect, fancy bodies bolted onto pickup frames, they cost very little to produce. When customers loaded them up with options, however, many sold for upward of $50,000. Those prices, combined with loopholes that allowed SUVs to avoid certain restrictions on fuel efficiency and suspension and braking systems that were required of passenger cars, gave automakers working margins of $10,000 per vehicle, turning individual car plants into the equivalent of Fortune 500 corporations. As sales of smaller SUVs, like Ford Explorers, Toyota 4Runners, and Dodge Durangos, also took off, American automakers placed their chips on SUVs, essentially abandoning much of the midsized and small-car markets to the Japanese. That decision would later prove to have nearly fatal consequences.

Why the remarkable surge in sales? One reason was pure quality: These vehicles always performed well in dependability surveys, as did the trucks they were based on. America was always good at building light trucks, and consumers knew it. Another was the decline of the once popular minivan, which had an excellent safety record, sat seven or eight passengers comfortably, and boasted high gas mileage but had come to be associated with boring, stay-at-home soccer moms. A GMC Yukon or a Chevy Tahoe, on the other hand, could haul just as many people but was seen as bold, aggressive, sexy, and sporty. That image was a direct result of the advertising campaigns mounted by automakers. In 1999, for example, a full-page newspaper ad for the Cadillac Escalade featured the word “yield” in bold print and a close-up of a huge grille and opaque black windshield. It looked, according to Bradsher, “just like what you might see in the last second of your life as you looked out the side window of your car and suddenly realized that a big SUV had failed to stop for a red light.” In case you still didn’t get the message, the bottom of the ad featured another warning: “Please move immediately to the right.”

The marketers were also selling freedom, or the automotive version of it. From their origins in 1935, the Suburban and its siblings were sold as cars for the adventurous, for people who spent time outdoors. The idea was to pack up the kids and go, a message that resonated even more strongly considering that Americans were less likely than ever to actually do that. “Americans were working more hours than other industrial countries,” said Catherine Lutz, a professor at Brown University and the co-author of Carjacked: The Culture of the Automobile and Its Effects on Our Lives. “So there was a loss of leisure time. People wanted to believe that if they bought the SUV they would enjoy their family more, even though all these other things are going in the opposite direction. Vacations account for less than one percent of all car trips. So the SUV becomes a kind of wishful compensation for the loss of leisure time.”

The big SUVs also appealed to a fundamental sense of security. “We spoke to a Ford marketing person,” Lutz told me, “who said that when people say that they feel safe, they don’t just mean ‘I am not going to crash’ or ‘I am going to survive a crash.’ They mean ‘I am safe from terrorism, from crime, from financial uncertainty, from my government.’ Marketers have incredible amounts of sophisticated research on the things that drive people to buy these cars. It is not just about additional horsepower or an extra cup holder. It is about a broader set of feelings you get when you have the thing. ”

And people, as it turned out, were prepared to pay more and more for this sort of fortresslike luxury. How could the middle class suddenly afford a $39,000 Tahoe or a $44,000 Ford Expedition? Partly because of rising incomes and partly because of increasingly easy credit. But in much of the country—especially in places where the price of real estate was rising quickly—the source of the money was their homes. “Big ad dollars were being spent on the heavy marketing of these more profitable cars,” said Lutz. “Subsequently, people began borrowing against their home equity. So the housing bubble became a car and SUV bubble.” Texas, where more large SUVs were purchased than anywhere else, joined a handful of states in which the average cost of owning a car exceeded the average cost of housing.

The result was that the Suburban and its siblings soon became common sights in places like Boston and Chicago. Still, Texas remained the number one market for Suburbans, Tahoes, Yukons, and Escalades, accounting for 20 percent of sales nationally. By the early 2000’s, the parking lot at my H-E-B on Austin’s west side had become an almost humorous expanse of gleaming sheet metal in the form of pickups and SUVs. Tahoes, the market leaders, seemed ubiquitous. A group of half a dozen thirtysomething couples moved into my neighborhood; all, as though in competition with one another, bought full-sized SUVs, mostly Suburbans and Tahoes.

Socioeconomic lines also seemed to blur in Texas when it came to Suburbans, Tahoes, and Yukons. My daughter plays fast-pitch softball, a sport that has a distinctively middle-class to lower-middle-class economic profile. At tournaments around the state, we found the same thing as at our H-E-B: lots of large SUVs, mostly late-model GM vehicles, jamming into ballpark parking lots. Nor were they all driven by middle-aged folks. Jennifer Euwer, as it turns out, is not so exceptional after all. “Most people would be surprised at how young our buyers are,” said Rick Scheidt, Chevrolet’s executive director of marketing for SUVs and crossovers. “Full-sized SUVs have one of the youngest age profiles of any of our products. It peaks with those guys in the twenty-five-to-forty-five category with obviously higher incomes. When you think about it, they are the ones with families, with the need to show off, with the income to afford the vehicle.”

What was perhaps strangest of all is that, somewhere around the turn of the millennium, it became normal for any Texan to own a 5,500-pound hunk of metal with chrome wheels so big most people can’t lift them, a seating capacity of nine, and a cost that is higher than at least three models of the BMW.

It was also during this time that the beloved old Chevy Suburban became the poster child for middle-class selfishness and indulgence. The early 2000’s saw the first wave of anti-SUV literature, bearing headlines and titles such as “Axle of Evil.” Anti-SUV activists like California’s Sue Thiemann started slapping hundreds of fake tickets on Suburbans (“Subhumans”), Excursions (“Extinctions”), and other large SUVs. “I hate them for environmental reasons,” she told the San Francisco Chronicle. “I hate them for safety reasons. Most of all, I hate them for the self-centered, self-absorbed, moral-midget rudeness.” An evangelical group launched a “What Would Jesus Drive?” campaign on its website. An organization led by political journalist Arianna Huffington ran ads that equated SUV driving with supporting terrorism. “I helped hijack an airplane. I helped blow up a nightclub. So what if it gets eleven miles to the gallon . . . I helped teach kids around the world to hate America. I like to sit up high.” Perhaps the most sweeping condemnation was delivered by Bradsher, whose High and Mighty used Detroit’s own marketing research against it. He concluded that SUV buyers were “self-centered . . . less social, more sybaritic, and have a limited interest in doing volunteer work to help others.” The idea was that owners of big SUVs were more interested in self-assertion, aggression, and dominance. If this seems extreme—and most Texans accustomed to seeing middle-aged moms ferrying their kids about town in Suburbans would find it ridiculously extreme—it became the considered view of many people in America, particularly in the Northeast.

One of the biggest complaints involved safety. When I ask my friends why they drive Suburbans, they usually cite safety as a prime reason. Their response reduces to a basic law of physics. A GMC Yukon XL, for example, a vehicle that is bigger than most things on the road, simply wins in most collisions. You don’t have to be a scientist to understand that. Its high bumper—often well above the bumper of, say, a Ford Focus or Toyota Corolla—and enormous weight guarantee it. But this measure of safety, curiously, turns out to be misleading. It is undoubtedly true that a Suburban wins in a two-car crash with a small car. But there is more to safety than that. One of the main components is accident avoidance. A big SUV has never been prone to rolling over like its smaller cousins, but it is far less maneuverable than a car. And that weakness, it turns out, often offsets its passive ability to protect its occupants.

A 2002 study conducted by Tom Wenzel, a researcher at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Marc Ross, a physicist at the University of Michigan, examined driver deaths from 1995 to 1999 based on the type of vehicle. It examined fatalities per millions of cars sold for the drivers of the vehicles and for the drivers of other cars involved in the accident. The study’s conclusion was that SUVs were “not necessarily safer for drivers than cars and on average they are as risky as the average mid-size or large car and no safer than many of the most popular compact and subcompact cars.” The Toyota Camry recorded 41 driver deaths and 29 deaths of drivers in the other vehicle. The Honda Accord had 54 driver deaths and 27 deaths in other vehicles. Chevy’s Suburban, meanwhile, tallied 46 driver deaths and 59 other deaths. The Tahoe’s numbers were 68 and 74. While the big SUVs were not notably less risky for their drivers than these other brands, it was indisputably true that fewer drivers survived collisions with them. SUV drivers were not nearly as safe as they imagined, but they were themselves quite as deadly as they had imagined. That much, at least, was observably true. None of which helped their image with the people who already hated them.

But as sales of full-sized SUVs rose to record levels in 2003, this criticism seemed to have no effect on the market. People wanted the cars. Such information was a mere faint buzzing in their ears, a bit of white noise they did not need to pay attention to. Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie drove their Suburban to McDonald’s with the kids. The mayor of Detroit cruised the city in a tricked-out Tahoe. Rapper Ludacris drove his Escalade onto the stage at the MTV Video Music Awards. Most of the players in the NFL and NBA seemed to drive some version of them. They were celebrity cars, yes, but they also looked great, even iconic, sitting in driveways—the perfect family car for the prosperous American family. American automakers were so confident in the market for them and for other SUVs that they had staked their future on them.

Then everything went wrong. It did not happen all at once, and it did not happen simply because gas prices rose to $4 a gallon in the spring of 2008 or because, a few months later, the subprime lending crisis knocked the world economy off its axis. The market for big SUVs actually faltered long before that. Their best year came in 2003, when they owned a record 4.6 percent share of the market in North America. The next year sales went flat. Then, in 2005, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita hit the Gulf Coast, causing a temporary spike in the price of gasoline. This certainly spooked drivers. But that alone could not account for the change in sales of Suburbans, Tahoes, Expeditions, Armadas, Sequoias, and the rest, which fell a whopping 25 percent when the rest of the auto business was enjoying a banner year. In Texas—the great bellwether of the market—sales were off nearly as much.

In 2005 consumers had already begun to switch to the more practical so-called crossover vehicles, like the Toyota Highlander, Chevy Equinox, and Nissan Murano. If you have not noticed, crossovers are the future of SUVs in general: They are built on car platforms instead of truck platforms and will soon replace most or all of the boxy, five-passenger Ford Explorer and Toyota 4Runner styles. They seat as many people as big SUVs but cost less and consume far less gas. The market dropped abruptly again in 2006 and 2007, and by 2008 it was in free fall as the recession gutted automobile sales around the world. Credit tightened and housing prices fell, meaning that people could no longer use their homes as piggy banks to buy $40,000 vehicles. Millions lost their jobs and thus the ability to afford car payments. GM, with its disproportionate portfolio of expensive, gas-guzzling trucks, suffered worse than anyone. By 2009 the damage was complete. The domestic market had plunged from nearly 17 million vehicles to 10 million. Of that, the big SUVs now owned merely 2 percent, a 54 percent drop in their share of the overall market in six years.

Extinction seemed imminent, and with all the talk of hybrids and cars that ran on water or vegetable oil, automakers braced for the worst. But in yet another twist, the Suburban and its cousins were saved by a core group of consumers who refused to let the vehicles go to the graveyard.

Sixteen miles from the Arlington assembly plant is Classic Chevrolet in Grapevine, the number one Chevy dealer in the nation. Touring the sprawling, six-building lot, where thousands of new cars stand gleaming in their ranks, one would never know that the car industry was in a grinding recession or that Classic’s supplier was a recently bankrupt ward of the U.S. government. Flags flutter and customers cruise the long lines of vehicles, kicking the tires, jawing with salesmen, and inspecting popular models like the Malibu, Traverse, Equinox, and Camaro. Here too are hundreds of Tahoes and Suburbans, ranged in their red, white, gold, silver, black, and gray colors, looking like so much candy in a box. Business is still way off for the big SUVs, but inventories and production have been adjusted, and Classic is selling all that the Arlington plant can give them. Chevy has even offered a deluxe “Diamond Edition” Suburban to celebrate the car’s 75 years of continuous production.

Considering the extent of the disaster, how did GM’s full-sized-SUV lines survive, particularly when the company had shown its willingness to let entire brands, like Olds, Pontiac, and Saturn, die? One answer is the loyal group of buyers—the largest concentration of which is in Texas—that is not going away in spite of the shift to crossovers and smaller vehicles, the iffy economy, or nervousness about gas prices. “What has happened is that we have gone back to more of a core buyer,” said Chevrolet’s Rick Scheidt. “We started out with people who needed towing capacity or just the ability to haul people. In the go-go years these full-sized SUVs became upscale products. People bought them because it said something about who they were. But the reality is that many of them did not need a vehicle that size. Now we are back to a core set of buyers that are family-oriented. They really need the size of the vehicle. We think that change has probably settled out. We don’t expect significant decreases in the numbers of vehicles.” Jeff Schuster, an executive director of automotive forecasting for J.D. Power and Associates, agreed with Scheidt’s optimism. “These vehicles are part of the portfolio,” he said. “Their market share will probably be in the range of 1.8 to 2 percent for the next four years. I don’t see a tremendous amount of change.”

Unless, of course, gas prices go up, in which case nothing is certain at all. Suburbans and other big SUVs have always been vulnerable to global swings in oil prices. Following the explosion of oil prices in 1979, for example, sales of the Suburban fell from 52,000 to 19,000. The price spikes after Katrina and Rita hurt too, and recession or no, $4 gas would likely have caused even more devastation in the marketplace. It is too soon to tell if the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf will affect oil prices, but curtailment in offshore drilling almost certainly will.

GM’s answer to gas prices is for sale on Classic’s lot too: the new Tahoe hybrids, vehicles that average 22 miles per gallon in the city, the same as a four-cylinder Toyota Camry. My loaner Tahoe was a hybrid as well, riding on mostly battery power at low speeds while giving the driver the option to kick the enormous gas-powered V-8 into action at will. Right now consumers are reluctant to pay the $4,000 premium for the hybrid option. Sustained higher gas prices would likely change their minds, and in any case the future of the full-sized SUV will feature lots of hybrids. The Arlington plant can switch production almost immediately if the demand exists.

For now, however, gas is $2.75 a gallon and cars are moving briskly off the lots in the Metroplex. “We’re doing much better,” said sales manager Ken Thompson with a confident smile. “We think we’re going to have a pretty good year.”