IN FROM THE ABOVE-NINETY heat of the El Paso sun on a mid-June afternoon in 1967, Genevieve Coonly picked up her ringing telephone and shrieked with surprise as soon as she heard the first words from the caller. “Hello, Bebe.” It was the unmistakable voice of Terry Allen, Jr., who was not only her nephew-in-law but also one of her and her husband Bill’s closest friends. What was he doing home? It had been only a few months since family and friends had gathered in Hart Ponder’s back yard for the farewell party when Terry left for Vietnam, and now he was back even though he had been scheduled to be gone for at least a year. Bill Coonly jokingly accused his wife of “getting out the fatted calf for the favorite son” as she prepared a luncheon feast for their surprise visitor, who had asked if he could stop by to talk. But as soon as he arrived, it was obvious that he was in no mood to eat heartily or laugh about old times.

He had come home from Vietnam, Terry Allen said, because his wife, Jean Ponder Allen, the daughter of Bebe’s sister, had written him a letter announcing that she was disillusioned with him and the military and the war and had left him for another man. This other man, literally a clown—Terry had heard that he was a rodeo clown who had appeared on a show produced by the local television station where Jean worked—had moved into the Allen house with Jean and his three little girls while he was fighting for his country on the other side of the world. Terry hoped to save the marriage but was unsure about the prospects. He thought that his mother and father, who also lived in El Paso, were unaware of the situation, so he did not want to stay with them. The Coonlys invited him to sleep in a guest bedroom at their house while he tried to work things out with Jean, and they lent him one of their old cars for the week, a pink Cadillac.

The sudden way his life had veered off track left Terry disoriented. Not so long ago it had seemed that things were perfect, he said. His mother’s family, the Robinsons, and Jean’s family, the Ponders, had known one another for decades, two branches of the El Paso establishment with former mayors on both sides. The fact that Jean was thirteen years younger had never given him reason for concern. How could it, when there was a twenty-year gap in the ages of his own parents, the retired general and Mary Frances, who had precisely the sort of marriage he sought to emulate? His life had followed a straight and clear path from childhood, but now here he was, out of place in his hometown, confused and lost. The first time he got behind the wheel of the pink Caddy, he drove through the streets until he ran out of gas.

TERRY DE LA MESA ALLEN, JR.,certainly had some choice in the life he would live, but the moments of doubt were rare. Imagine being a boy of thirteen in El Paso, and it is just before Christmas 1942, the war is on, and day after day you and your friends read and hear about the heroic deeds of American GIs fighting in North Africa against the Vichy French and the Nazis and in the Pacific against the Japanese, and you run around the neighborhood near Fort Bliss pretending to be soldiers. And then a letter arrives like the one that came from Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen, Sr., postmarked December 8.

“My dear Sonny,” the old man began, using the loving nickname he called his namesake and only child, whose picture he carried with him in a leather pocket case. He was enclosing a $20 money order for a Christmas present, which he would have preferred to pick out himself but found impossible to do, given where he was and what he was doing, which was in North Africa commanding the First Infantry Division. But he had another present for his son that would be delivered specially by a staff officer heading back to the States on emergency leave. It was a flag of the Big Red One, as the infantry division was called, that his assault units had carried when they landed in Algeria, perhaps “the first American flag to be landed on the shores.” Later, that same flag was “carried on a Tommy gun” by a soldier in General Allen’s Jeep until it was retired from service and “marked and embroidered by some of the French nuns in a nearby convent.”

The war relic was an expression of a father’s love but also served as a reminder of his expectations, and it was that combination that defined the bond between the two Terry Allens from the time of the son’s birth, on April 13, 1929. It was not intimidation or fear of being a disappointment but deep affection and constant tutelage that funneled the son down the narrow chute of his family’s military tradition.

The soldier’s life went back another generation to Samuel E. Allen, a West Point graduate who served 42 years as an artillery officer in the regular Army and who was married to Conchita Alvarez de la Mesa, of Brooklyn, the daughter of a Spanish colonel who came to the U.S. to fight for the Union during the Civil War. Samuel Allen was said to be unassuming and conventional, traits that never came to mind at the mention of his son, Terry, who began his career as a hell-raiser at West Point, where he earned his first wild nickname, “Tear Around the Mess Hall Allen.” He hated math, found schoolwork tedious, stuttered in the classroom, and flunked out of the academy. His determination to become an Army officer pushed him back to school at the Catholic University of America, in Washington, where he earned a degree and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. Over the next three decades, he rose up the Army ranks with a reputation as an uncommonly beloved leader who was disdainful of any rule or bureaucratic regulation that he thought inhibited the fighting spirit of his men.

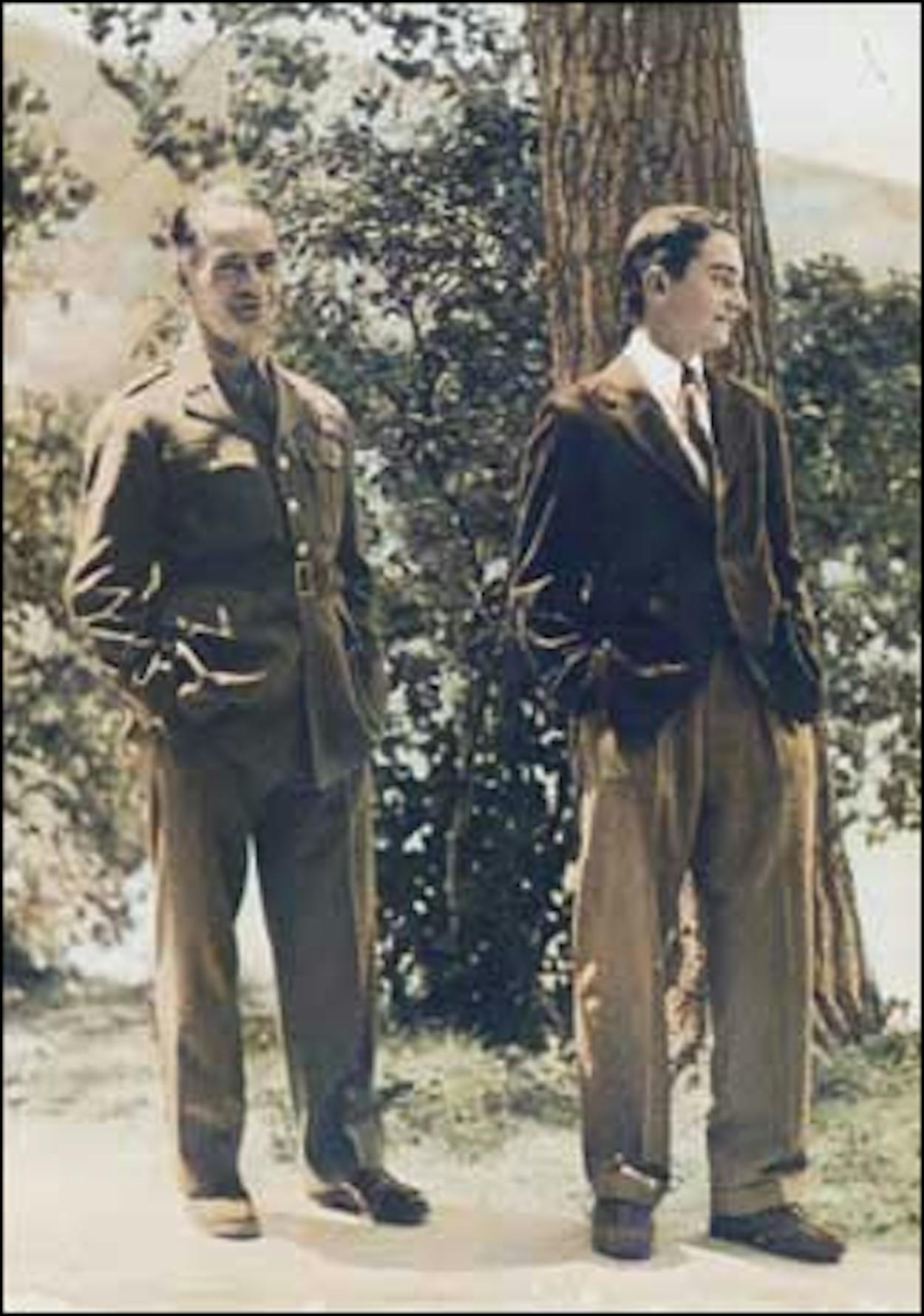

The general’s devotion to his soldiers, and their loyalty in return, was repeated tenfold in the relationship between father and son. Terry Allen, Sr., was a skilled polo player whose horsemanship was legendary, going back to 1922, when, as a cavalryman riding a big black Army horse named Coronado, he defeated the Texas cowboy Key Dunne in a long-distance horse race between Dallas and San Antonio. Whatever he loved, he wanted his son to love as well. Sonny was only two when he was placed on his first saddle at Fort Oglethorpe, in Georgia, and six when he took riding lessons while his father was stationed with the Seventh Cavalry at Fort Riley, Kansas. A love of polo was also passed along. Terry Junior learned the game before he was ten and later became team captain at the New Mexico Military Institute, his career fostered by Terry Senior from afar.

General Allen’s passionate interest in his son’s polo development was surpassed only by the zeal with which he pushed for Terry Junior’s appointment to West Point. He lobbied virtually nonstop starting in August 1944, when his son was only fifteen and he was in Colorado Springs organizing the 104th Infantry Division, known as the Timberwolves. He took time out then to meet with Senator Tom Connally, of Texas, to press for the appointment, though it was still several years off, and followed that with a letter extolling Terry Junior’s qualifications. Letters went out regularly to influential friends and politicians in Austin, San Antonio, Houston, and Washington, all the way up to Vice President Truman. First Lieutenant Alfred Wechsler, of Connecticut, a loyal Timberwolf, wrote letters to several Democratic politicians in his home state, including one to state senator Matthew Daley that pleaded the case in blunt terms. “The General has only one boy who is fifteen years of age and he is the apple of the old man’s eye,” Wechsler wrote. “The General’s paramount wish is to have his son follow the family tradition of professional soldiering.”

It took all of that lobbying and cajoling, plus a year of remedial tutoring at another military prep school, but Terry Junior finally made it to West Point on a senatorial appointment in 1948. As a cadet in Company H-1, he became known for “his good nature” and “burr-head haircut.” He was in the Spanish club, played polo, and boxed. At Christmastime 1949, when his mother, Mary Fran, came to visit, she stopped by the gymnasium and distracted him just enough for his sparring partner to break his nose, an accident that later prompted a letter of reassurance to Mrs. Allen from Colonel Earl W. “Red” Blaik, the West Point football coach and athletic director. “Like boots and spurs to a cavalryman, a broken nose is a mark of manly distinction to a youngster, and in cases where they have been properly set there is no reason to worry about whether such a break will affect either the good looks or the health of the individual,” Blaik wrote. Cadet Allen was regarded as “a good listener,” though in a classic understatement, the Howitzer yearbook confided that he was “never an academic standout.” In fact, he finished second to the bottom of the class of 1952, one man away from being the goat of his class. It mattered not at all; he had survived West Point where his father had not, and though his personality was different from the famous general’s, his classmates noticed in him many of the same leadership skills that would prove more important in his chosen career than an aptitude in mathematics. “On occasion,” a classmate later wrote, “he would use a heartfelt yell and a slap on the back as a means to influence those around him.”

Lieutenant Allen reached Korea with the Fifth Infantry Regiment in 1953 at the end of the conflict there and then returned home to Fort Lewis and began an ascent that paralleled his father’s four decades earlier. Terry Senior was watching his son’s progress with more than casual interest, as attested to by a letter he received on December 20, 1955, from John C. Schuller, a life insurance agent in El Paso who had inside sources at the Pentagon and was able to obtain Terry Junior’s personnel records. “Terry has an OEI (Officer Efficiency Index) of 132 as of now. This is a numerical evaluation now being given officers based on their efficiency reports. 150 is the max. 132 places him well up in the upper one-sixth of all first LTs in the Army. In other words, he is highly outstanding among officers in his grade.” Schuller went on to assess Terry Junior’s prospects for getting into advanced officer-training courses and promotion to captain. (“Here again no worry because he has such a fine record.”) All of which surely pleased the old man, who was by then retired and living in El Paso. The family ambition, shared as well by Mary Fran, was for Terry Junior to exceed his father and someday wear the three stars of a lieutenant general or four stars of a full general.

After reaching captain, he served as a staff officer for the Continental Army Command in Fort Monroe, Virginia, and then was sent west to Colorado Springs as a junior aide to General Charles Hart at the U.S. Army Air Defense. That is where he met Bebe and Bill Coonly, when Bill was Hart’s senior aide. The dashing young bachelor captain drove around town in a 1957 Thunderbird convertible with his polo boots and mallets in the back seat. He stopped over at the Coonlys almost every day or night, sometimes as late as two or three in the morning, knowing that he could bang on the door at any hour and feel welcome. On his way home from a party, he might “come in smiling expansively” and pronounce to the groggy Coonlys that his father had always told him never to drink alone. The life that his father had helped shape for him looked fine indeed in those final days of the fifties, and on the first of April, 1959, Terry Senior’s birthday, the loving disciple sent home a telegram that read “My best wishes from the luckiest son in the world—Sonny.”

GENERAL ALLEN AND MARY FRAN lived in a comfortable but unpretentious house of limestone and wood at 21 Cumberland Circle, within a mile’s jog of the Fort Bliss front gate. On the living room wall, above a long row of polo trophies and wartime photographs, were the battle flags of the Big Red One and the Timberwolves, along with a painting of Terry Senior that appeared on the cover of Time in August 1943. The rest of the house, with the exception of the retired general’s den and Terry Junior’s old bedroom, was painted in Mary Fran’s favorite shade of art deco pink. Terry Senior sold insurance in his retirement, though he never made much money at it, and he spent a lot of his time corresponding with old soldiers, coaching the polo team at Fort Bliss, and trying to keep in shape. Long before running became a fitness craze, he could be seen jogging through the residential streets in a loop that took him to the military base and then around toward the fashionable stucco homes on Pennsylvania Circle, where El Paso’s social elite lived. He was an unforgettable sight, decked out in Army sweats with a wool wrap around his neck, carrying a medicine ball that kept his wrists supple for polo. When Jean Ponder, looking out from the back yard of her home at 230 Pennsylvania Circle, first saw this old man running down the nearby alley in the noonday heat, she went inside and asked her mother who it could be and was told that it was General Allen.

There are conflicting accounts of when she first met the general’s son. As her aunt Bebe Coonly remembered it, she and Bill threw a party for Terry when he came home from Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, a training ground for future colonels and generals that the near-goat of West Point had become the first member of his class to attend. Bebe’s sister Alice Hicks Ponder called and asked her to invite her daughter Jean, a gorgeous coed who had been moping around the house, depressed about being dumped by the young man who had been her escort the previous year when she was named the lady-in-waiting at the Sun Carnival. “And Jean walked in and looked like a million dollars, and Terry had been laughing, drinking, and talking and then just froze at the sight of her, and that was it,” Bebe recalled. Jean remembered it differently. She was home after her freshman year at the San Diego College for Women, and her mother came up to her room and said that Terry Allen, Jr., was downstairs—would she like to meet him? Jean said no, her mother insisted, and Jean relented but said that she would not change out of her Bermuda shorts. So she went downstairs and the introductions were made—and from there “a whirlwind romance” began. They were both on the rebound, both Catholics. His family was revered in El Paso, and she felt safe around him. To him, she represented the second coming of his mother, once a beautiful young socialite. He was 32, she was 18. It was as though they had no choice but to accept the social scripts that were handed to them. He proposed in July 1960, and they were married in October.

After a honeymoon on the French Riviera, Jean Ponder Allen found herself in a quaint place called Bad Kreuznach in an alien country where she knew no one and barely knew her own husband, who worked long hours in any case and usually took the car. She was utterly ill prepared for the life she faced, a spoiled beauty queen from upper-class El Paso accustomed to nothing beyond the privileged society of her youth. Her landlady, Frau Schmidt, whose husband had fought for the Nazis, took pity on her and taught her some German. She made daily strolls around the village. And in less than a year she had a baby daughter. Terry wanted to name her in honor of his Spanish grandmother, but he somehow confused the name, so it came out Consuelo instead of Conchita. In a letter to her mother-in-law in September 1962, Jean seemed to be adjusting as well as could be expected. “Terry is in the field again—for ten days,” she wrote. “Everyone is a little nervous around here, as in four days five Eighth Division people were killed. Two in an auto accident, one jumping, and a sergeant shot a captain and then killed himself! All of this took place in Mannheim—is B.K. next? . . . Oh, Mary Fran, if only you could see your granddaughter now. She is cute enough to eat. She has discovered her hands now, and spends hours looking at them.”

Another daughter, Bebe, named for Jean’s aunt, arrived fourteen months later, and within a year of that came Mary Frances, named for Terry’s mother. Jean was barely 22, the mother of three little girls, overwhelmed and overtaken by postpartum depression. She was also without the help of Frau Schmidt after the family moved to Stuttgart and then Augsburg following Terry’s promotions. His mind was very much on making it to the top. Without saying it aloud, he and Jean worked on the common assumption that someday he would be a general.

After two years with the Seventh Armored tank battalion, Terry was transferred to the States for a post with the U.S. Strike Command at MacDill Air Force Base, in Tampa. Jean was depressed and emotionally drained by the time they got back from Europe. She was drinking to medicate herself in the evening, though it was not especially noticeable in a family of habitual drinkers. Terry, like his father, rarely let the cocktail hour go by without two scotch and waters, which he sipped while puffing on an aromatic cigar. He was a lively storyteller and had a natural brightness to him—some called it a twinkle—that perhaps made it harder for him to see Jean’s inner despair. In tandem with her drinking, she was taking amphetamines, one tablet of speed a day to help her lose weight. She was also distraught over the condition of her mother, who was in the final stages of inoperable stomach cancer. Her mother was her emotional mainstay, but now Jean felt unable to even express her distress. Jean’s father had issued a family order that no one was to talk about the fatal nature of the disease, particularly not in front of his wife. Alice Ponder died in April 1966, while Jean was in Tampa, and her father quickly remarried, making the young military wife feel even more alone.

Out of whimsy and desperation, Jean visited a fortune-teller. Her life, she was told, was like a piece of cloth that was going to be ripped in two. Her husband might die. “Ridiculous,” Jean said to herself. “That’s what I get for going to a stupid fortune-teller.” Then Terry Allen, Jr., was ordered to report for duty in Vietnam on February 25, 1967. He had often told Jean that “the only way a soldier proves himself is on the battlefield.” Here was his chance. Jean, in retrospect, thought she should have asked him to hold off going until she was in a better mental state, but at the time, she and her husband were still operating under another philosophy: In the military, you do what you are told to do. She still wanted to be a general’s wife.

THE OLD MAN HAD FALLEN into a middle stage of dementia by then, a condition that first became noticeable during a trip to the battlefields of Holland with his old Timberwolves in 1965, when he kept wondering where he was and asking in befuddlement for Mary Fran, who had not made the trip with him. For Terry Junior, who adored his father, watching him deteriorate was like “watching the sun fall from the sky.” By early 1967, when his son flew off to lead soldiers in Vietnam, the retired general was virtually unable to navigate outside his home and would lapse into periods of confusion. He held on dearly to reminders of his glorious past and became obsessed with the little red instructional booklets he had published during and after World War II. He carried them in his back pocket wherever he went and would hand them out to strangers and children, including little Consuelo. Among the personal items Terry Junior took with him to Vietnam was a small brown manila clasp envelope that had “For Terry Allen jr. (All you need to fight a War)” written on the side in a palsied scrawl. Inside were three of the booklets: Directive for Offensive Combat, Night Attacks, and Combat Leadership, the final words of which were “The battle is the payoff.”

In late March, during a rare lull in his job as operations officer for the Black Lions battalion, the position he held during his first two months in Vietnam, he wrote a long letter to his young wife. “Dearest Jean,” it began. “I was thrilled to receive three letters from you while on this last operation. The first letter arrived on the 19th and it was postmarked from El Paso on the 14th. This was the first letter I had received—if you had written before and included any information requiring an answer etc. please let me know. I read the letter so many times the handwriting would rightfully have come off the paper. Any break I had I would pull them out and reread them—I do miss you terribly.” Jean had in fact written him almost daily in the first few weeks after his departure, loving letters in which she talked about how fortunate they were “to have such a strong bond.” She was beside herself to hear that he had not received them.

The next paragraph was equally warm, and it seemed apparent that he was thinking of Jean as his soul mate as he described life at the base camp. “It’s good to be back to our base camp to clean up and sleep in a bed. This is the fourth night we’ve been able to spend here since my arrival in the battalion. It’s a little relaxing and the one place I can use a fan (which I intend to buy shortly). We will be here six days before leaving on another operation. Tomorrow is Easter so I will be able to go to Mass. Our battalion chaplain is a Catholic—a Jesuit and a very fine soldier priest. We had some interesting discussions over a drink after our Junction City Operation. We both agree on so many points—wish you had been there to join us.”

The remainder of the letter was all military, nothing personal, describing in great detail the last operation 35 miles north of Saigon as though he were filing an after-action report to headquarters. If its intended purpose was to familiarize Jean with his environment, it did the opposite, only making him seem a million miles away.

How different that world of the Black Lions seemed from what Jean was experiencing in El Paso. Terry Allen, Jr., might still be playing by the script, but hers was not unfolding the way she had expected. Her mother had died. Her father had remarried within six months. Her husband was in Vietnam. She had three small girls to look after, and no one in El Paso to whom she felt close. In that difficult and isolated condition, she felt the first undirected stirrings of something else, a need to break away and reinvent herself. In a visit to the new television station in town, ABC’s Channel 13, she proposed that they let her run her own weekly public-affairs show. She was a striking figure in her short skirts, with long legs and flowing light-brown hair. She was also articulate and her family was well known, and such a show would cost little while satisfying the regulatory requirements of public-interest broadcasting. In the spring of 1967, The Jean Allen Show was born.

Airing Sunday afternoons at two, it was the typical local patchwork of the serious and the inane. Jean interviewed artists and authors and let local theaters perform snippets from their shows, but there was also the time when a dairy manager bragged about his best-producing cow, pulling out a picture of the cow and, in a deadpan voice, discussing the number of gallons she could let loose in a day. The show brought Jean into contact for the first time with people who were critical of the war in Vietnam, and day by day their thoughts altered her perspective. She noticed that people, even anti-war activists, seemed impressed that she was the wife of an Army officer, but she was becoming less so. For the first time, she began “to see the other side of the story in Vietnam,” she would say later, and she embraced it as naively as she had previously “embraced not questioning politics.” She did not move to the other side gradually but suddenly, and it was more out of emotion than careful study. She was seeing life in a way she had never seen it before. Until then she had carried “abstract feelings with echoes of World War II in the background,” but now she was “watching television and seeing body bags brought out and scenes of villages where civilians had been bombed.”

This was all very different for her, and she was having a visceral reaction. As the weeks went by in April and May, she could no longer make a distinction between her husband as a soldier and the military as a whole. If it was wrong, so was he. She began seeing the world as us versus them, and Terry Allen, Jr., was one of them.

“A VERY SPECIAL PLACE MUST be reserved in Heaven for Army wives as reward for the years of separation they have endured because of military requirements . . . There can be no greater admiration than that of the husband to return and find, as he has hoped, that his own wife has met the test of keeping up her end of things.” So began a section on how to be a proper Army wife in The Officer’s Guide, the standard bible of the soldier’s profession.

Jean Ponder Allen was no longer interested in following that path to heaven. She struck up a relationship with the TV clown, started sleeping with him, and soon invited him to stay at her place, a house on a street called—of all things—Timberwolf, named after the famed division that Terry Allen, Sr., had led through Europe and that nothing in hell could stop. She was in a state of mind in which she felt no embarrassment. Her daughters wondered who this strange man was in their house, who seemed to drink too much and who broke Bebe’s tricycle, but Jean was not thinking of her children as anything more than an extension of herself. She wrote Terry Junior a letter telling him what she was doing and how she felt. Terry called from Vietnam, but the connection was bad, figuratively and literally. Soon he was getting emergency leave, flying back to El Paso, calling Bebe Coonly and making her shriek with surprise.

He drove over to 5014 Timberwolf in the pink Cadillac and tried to win back his wife. She felt a need to defend her position and overstated it, calling him a baby killer. She remembered him saying that he had grown to understand a lot of things that he didn’t when he first got to Vietnam and that he was taking notes and would write a book about it when he got back. He was abandoning the lifelong dream of becoming a general, he told her. He didn’t know what he would do, maybe teach. The boy who considered scholarship tedious had evolved into a man who loved to read and was a voracious student of history. As Jean would remember it later, this was “in some ways maybe the most honest conversation we’d ever had between us.” They sat in the bedroom, man and wife, estranged and struggling. He said that he wanted to make love to her. She wanted to but would not let him. He kept talking about the war, offering nuanced explanations of what the American military was doing and failing to do. She was not interested in complexity, only in what she had seen and heard about civilians getting killed. It doesn’t matter what you say, she told him. It’s finished. She explained to him, for the first time, how upsetting it had been for her to have three little children and make so many moves, and he said he never should have let it happen. He asked her to see a psychiatrist, and she agreed.

Over at the Coonlys, the conversations were also, inevitably, about Vietnam. You wouldn’t believe how things are going over there, Terry told Bill. It was a whole new ballgame, nothing like what they taught at Command and General Staff College. Senior commanders didn’t seem to comprehend the reality of what was happening on the ground, in the jungles.

He drove across town to Timberwolf again the next night, when Jean’s sister, Susie, was babysitting the girls, and said that he just needed a minute. Susie was under instructions not to let him in, but she did. He stood in the doorway outside the bedroom and stared at his daughters as they slept, then he left. The next day he drove downtown to the end of Texas Street, where it meets Oregon, and stepped inside the First National Bank Building, riding the elevator up to fifteen, the top floor, finding his way to Kemp, Smith, White, Duncan, and Hammond, and from there to Tad Smith’s office in the northwest corner, where the picture windows lured the eye up Texas Street and on to the Franklin Mountains in the distance. Tad Smith was not a divorce lawyer, but he made exceptions for people he knew, and everyone in town knew General Allen. He encountered the general’s son now, who was “pissed off.” Terry said that he had staked out his wife’s house and seen the car of this “bozo the clown” there and that he wanted a divorce and also custody of the children. Smith said that would require the development of more information about Jean’s behavior, and Terry said there was a next-door neighbor who knew some things—a retired Army officer who had told Mary Fran about the affair. And the maids were talking. In El Paso, most Anglo families in the middle and upper classes had maids, and the maids knew each other. Jean’s maid was talking to friends.

Near the end of his leave, Terry spent an afternoon with his girls. He was wearing a Hawaiian shirt when he picked them up in the pink Cadillac, and they went to the Campus Queen for burgers and then to the swimming pool at the Coronado Country Club. When he dropped them off and started to say good-bye, about to return to Vietnam, where he would soon become battalion commander of the 2/28 Black Lions, little Consuelo hid under a three-legged stool and started crying.

“You can’t leave!” she sobbed. “You’re going to die!”

Terry Allen pulled his daughter up from her hideaway and held her in his arms. “Be brave,” he said, “and take care of your little sisters.”

On the morning of October 17, 1967, as he led his Black Lions battalion on a search-and- destroy mission in the Long Nguyen Secret Zone, northwest of Saigon toward the Cambodian border, Lieutenant Colonel Terry Allen, Jr., and sixty of his men were killed in an ambush.