Chapter One

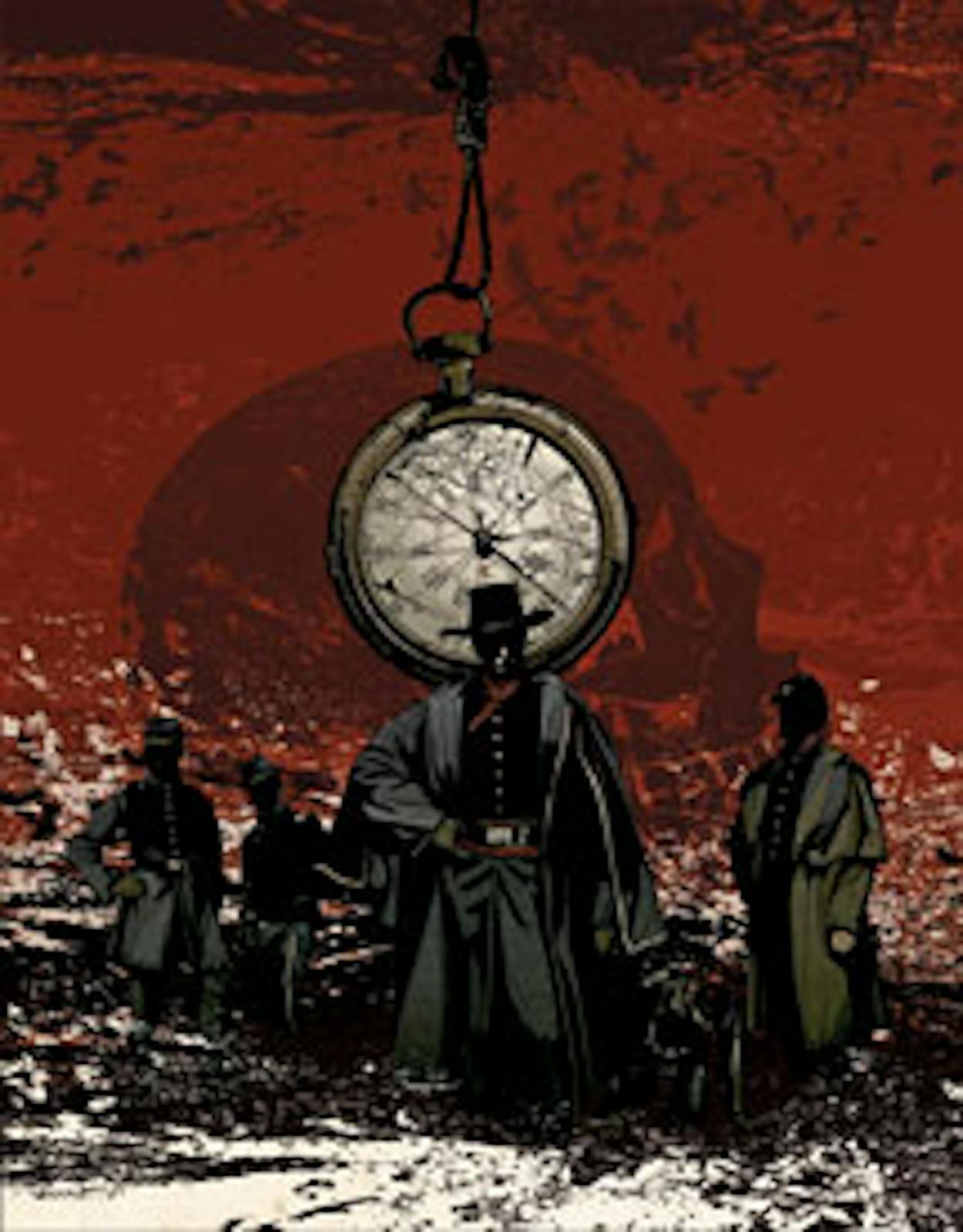

The fog coming off Shoal Creek was pouring through the prison yard in pearl-colored puffs that made him think of cannon smoke. Captain Jerod Robin lay on his back in the caliche mud with his head leaning against the south wall of the stockade. The Leatherwoods had smashed his pocket watch, but he thought it would be nearing a wet dawn if he could see the sun.

A chain around his ankle locked him to the steps of the gallows platform. Robin’s ribs ached from the stomping that had been laid on yesterday evening by Santana Leatherwood and his three nephews. Massaging his sore heart with his fingertips, Robin touched the letter the nurse at the hospital in Tennessee had sewn into the lining of his butternut coat. Several buttons had been torn off the double row down the front of his coat, but the letter was safe. If the Leatherwoods had found and read the letter, they would have murdered him yesterday on Pecan Street instead of beating him and throwing him into the bull pen and waiting for the judge to come and hang him to make his death what now passed for legal around here.

As Robin’s fingers rubbed the outline of the letter, he felt comfort in those folded pages of words. His life had been so distorted for the past three years—since Shiloh—that he might have been dreaming his existence. The letter was a real thing that confirmed the one hope that through it all had brought him back from madness and given him reason to return to the world—the hope that he still had a home at Sweetbrush and people there he loved who loved and needed him.

A smell of rotted meat floated through the fog, and then a groan.

“Help me,” a voice cried. “Will someone help me, for God’s sake?”

“That’s a laugh,” yelled another voice.

“Please. For God’s sake, help me.”

“Tell it to your preacher and let him holler up at heaven with your sad story.”

Laughter drifted around through the fog. Then silence settled as prisoners brooded their fates in the dark. The fog grew thick as snow to the touch and turned cool. Robin realized he was feeling rain on his hands and heard drops tapping on his hat. He lifted his head and opened his mouth and licked the moisture off his lips.

“Bastards coming,” shouted a voice in the fog.

More voices shouted, “Bastards coming! Bastards coming!”

“Quiet down, you putridity,” yelled a voice Robin recognized as Santana Leatherwood’s. Robin heard the chink of spurs. He saw a disturbance in the fog, where forms began to appear coming toward him.

“Jerod Robin, where you at?” called out Billy Leatherwood, the youngest and smallest of the three brothers approaching him in the fog. They were dragging a sack that had something heavy in it.

“Over by the heel fly, Billy. He’s chained up over that way,” said Santana, looming out of the mist behind his three nephews. There were gold tassels on the band of his wide-brim campaign hat that he wore tilted forward onto his forehead. His neck scarf and suspenders were yellow against the faded blue of his 7th Cavalry uniform shirt. Six silver conchos, Mexican style, ran down the outside of each of his black leather boots. His spurs were silver with two-inch rowels, mean ones.

“Here he is, Captain,” Billy said. “Laying here like he’s on a holiday with nothing to do. Why, I believe he’s asleep.”

“Give him a kick,” said Santana.

“Don’t touch me, Billy,” Robin said. “I’m keeping score on you.”

“Get up, then. The captain has brought you a new friend.”

Robin pulled his knees up and made it to his feet as the two elder Leatherwood brothers hauled their sack toward him. Robin was tall and pale, with sleepy blue eyes. In the fog he could barely make out the sullen features of the middle Leatherwoods under their round-top felt hats. Vapor floated around their faces. Santana stepped closer to Robin and gestured toward the sack.

“This fool stole General Custer’s brother’s horse,” Santana said.

What Robin had taken in the fog to be a sack he now saw was a man with his chin fallen onto his chest. Blood dripped from a black patch in the man’s gray hair and plopped into the dirt. Luther and Adam Leatherwood were holding him up by the armpits. His legs disappeared behind into the fog.

“This fellow is as big a fool as you are, Robin,” Santana said. “You and him are going to pay the same price for your foolishness. You’ll be jerking in the sky side by side, you and this foreign idiot. Put the horse thief down, boys.”

The Leatherwood brothers let go, and the prisoner hit the ground on his face.

“Chain him up next to young Robin,” Santana said. He bent near enough that Robin could see above Santana’s left ear a bit of silver plate that was a marker from battle in a war previous to the one that was now ending. “Well, Robin, life is uncertain, ain’t it? Full of twists and turns. When they talk about odd twists of fate, they mean you and me, don’t they? Seems like yesterday you was a rebel officer with a history and a future. But today you are a doomed fool chained up with an idiot who thought he could make off with Tom Custer’s famous horse from in front of Dutch John’s Saloon in the middle of the night.”

“This thief has to be real stupid,” said Adam.

“I mean, he’s dumb as a stump,” Luther said.

“The horse he tried to steal is the very same horse Tom Custer rode at Namozine Church and three days later at Sayler’s Creek when we were chasing you rebel cooters through Virginia three months ago. You’ll be glad to know I got back into action in time for the finish of this war. I saw Tom Custer win two Medals of Honor in one week on the back of this very horse. This is a legendary horse. Can you picture the confusion in the mind of a person who thought he could climb on Tom Custer’s horse and ride out of town?” Santana said.

Billy was fastening a chain on one of the horse thief’s ankles.

Billy said, “Robin, you should of heard this thief trying to talk his way out. He was talking an owl out of a tree is what he was doing. It was comical.”

“So you bashed his head,” Robin said.

“Adam bashed his head. Then Luther let go another bash,” said Billy.

“I got him good,” Luther said. “He might be dead.”

“He ain’t dead. Look at him. He’s bleeding,” said Adam.

“Uncle Santana just now done that gash with his spurs,” Luther said.

“Still. You ever seen a dead man bleed?” said Adam.

“Plenty of times,” Luther said.

Round splatters dappled in the dirt as heavy raindrops fell through the fog.

“You never,” said Adam.

“Don’t give me that cockeyed look,” Luther said.

“You boys pay attention here,” Santana said.

Billy wrapped the horse thief’s chain around a post of the gallows platform and locked it with a click. The two older Leatherwood brothers wore red bandannas knotted at their throats to show they belonged to the company of Home Guard, which was cooperating with the federal regiment that had begun arriving in Austin to start imposing law. Outside the prison gate there was disorder and fear. The elected governor of Texas had fled to Mexico. Buildings had been sacked. Returning rebel soldiers were passing through the capital city, often barefoot and injured and penniless, with anger in their hearts and exhaustion on their faces. Citizens and refugees were rushing through the streets carrying bags of coffee, flour, sugar, salt, bacon, cloth, rope, leather, cotton, whatever they could snatch. The public mood was to catch what you could and hold fast to what you got.

The horse thief lifted one hand and spread his fingers and touched them to his hair. His fingers felt blood and froze. The rain shower was passing, but the fog was dark and wet. The Leatherwood brothers stepped back from the prisoner and became half-lost in the mist. Santana looked down at the bleeding head of the fallen horse thief and then raised his eyes to Robin.

“In far-off Tennessee you had thirty mounted men under your command.” Santana’s eyes sparked with humor and intelligence. He grinned and showed a healthy set of white teeth. “Now you come back home to Texas, and what do you find? You find a date with a rope. A cruel ending to your story, but fitting. You and I both know you are without honor. You deserve to die like a rat.”

“What charge could you hang me on?”

“I made a list. Murder is at the top.”

“You know I didn’t kill that old man,” Robin said.

A loud, sharp bang crackled through the fog. It was an explosion from the south part of town, where the river turned toward the southeast and headed for the Gulf of Mexico, two hundred miles away.

Santana said, “We’ve got quite a few guerrillas that need to be subdued. In Texas the war ain’t over no matter if General Lee and Joe Johnston and Jeff Davis and every cracker in the whole rest of the South may have quit. They still love to string up abolitionists here. Appomattox is just a tick on a hog’s back as viewed from Texas. But when the people here do learn they’ve lost the war, they’ll keep fighting anyhow, because fighting is their nature. You’ve known my nephews since they was children down on the bayou. You ever remember a day when they wasn’t spoiling for a fight?”

“I remember a day they showed pure yellow,” said Robin.

“Not in history has there ever been any yellow in any Leatherwood.”

“The day the recruiter came gathering men to fight the war, your nephews ran and hid in the forest,” Robin said.

“Because you’re on the wrong side, Robin. You’re fighting the rich man’s war.”

“You’re a traitor to Texas,” said Robin.

Santana licked his teeth and then spat onto the horse thief’s back.

“See what a fool you are?” he said. “I am Texas now. You are done.”

Santana turned and took two steps and vanished in the fog with his silver spurs chinking and his nephews following. Billy looked back, shook his head, and chuckled. He said, “Jerod Robin, you are sure going to suffer for your sins today,” before the gray mist covered him.

Robin knelt and gave his attention to the horse thief.

Chapter Two

In his mind Varney was back in Afghanistan.

He was hearing drumming and screaming. His skull was throbbing and his stomach flopped as if he’d drunk too much of that bloody fermented whatever the hell it was the Ghilzai headman served in that blasted bone cup that looked like his grandmother’s knee.

Varney had woken up from a concussion to find himself sprawled in the snow in a clearing surrounded by mud huts with rusted tin roofs made from British ammunition boxes. The wild Ghilzais were squatting on their haunches in the snow, clutching their knives and long rifles, smoking and laughing at him. He sensed now that his head was bleeding, as it had been that morning in the village in the Hindu Kush, near the pass where the British Army and their women and children and servants were being slaughtered that very day on their retreat from Kabul, all killed, all 16,000 dead. Varney’s fingers felt wet and sticky from touching his scalp, not at all a good sign.

He opened his eyes into a squint and peeped out, expecting he was going to see the bearded Ghilzai warriors capering in their pantaloons, their sheepskin cloaks scattering snow, swinging Varney’s ruby amulet on its gold chain in a loop around their turbans and fur caps, the headman mounted on Varney’s beautiful horse Athena, prancing in the snow.

But he saw cool gray smoke enveloping him instead. He heard voices cry out from somewhere in the smoke on the far side of wherever this was. One voice screamed, “Mother of Jesus, get away from me or I’ll kill you.” This sounded like what you might hear in Kabul, but Varney began to realize it wasn’t smoke he was seeing, and these cries were not in the Pathan tongue but were in English of a sort, the slurred tones of the Southern mountains, the flat drawls of the West. He began remembering that Afghanistan was years ago, though it seemed recent and was always near the front of his mind. He was among a different breed of savages now. He was in Texas.

“My God, this bloody fog is worse than London,” Varney said. “Who would have believed it? I can’t see the end of my blasted feet.”

Varney tried to move his right leg and discovered he was chained. Behind him, hidden by the fog, Robin stood and watched. Varney grasped the chain in his strong right hand and yanked, but it rattled and held. He reached out with both hands and tugged again. Robin saw the swell of muscle in Varney’s neck and shoulders. Varney dropped the chain. He licked blood off his upper lip. He touched the bleeding lumps on top of his head where the hair had gone thin, a patch of it torn out.

Somewhere in the fog a voice yelled, “Please, I’m asking, will somebody help me?”

Another voice yelled, “You’re in hell. What do you expect?”

Varney looked at the blood on his fingertips. His face had a patrician aspect, a heavy brow, a well-drawn nose and chin. Robin was thinking this horse thief’s head looked like a long-buried bust of an ancient Roman senator, with the dirt still on it, but the body was sturdy and blocky, like that of a laboring man. Robin guessed the horse thief to be about fifty years old, about twice Robin’s age. The horse thief’s left earlobe was pierced by a green earring that looked to Robin like jade laid on silver.

Varney shouted into the gray curtain, “If you think this is hell, you have sorely underestimated the devil. I have visited the afterlife and have returned. This isn’t hell, you bloody yobs. This is only Texas.”

The prisoner’s accent sounded familiar to Robin. It was an upper-middle-class En-glish preciseness, like that of Robin’s mother, who had been born in St. John’s Wood, in the north of London. Despite nearly thirty years in Texas, Varina Hotchkiss had maintained the sound of London in her accent. The rhythms of the prisoner’s voice reminded Robin of her.

Varney looked down at his fist wrapped around the chain. “Hullo,” he said, noticing another chain. He clutched the second chain in both hands and began to haul it in like a fisherman retrieving a net. Twelve feet away at the other end of the chain was Robin’s right boot.

“What’s this, then?” Varney said.

The prisoner peered at Robin emerging from the fog so close by. Robin could see he was struggling to clear his mind from the blows that had been lavished onto his head by the Leatherwoods.

“Let me take a look at your wound,” Robin said.

“Are you a physician or merely morbidly curious?”

“I have some experience with wounds, but if you’d rather not, the hell with you.”

“I’ve already been to the afterlife,” the prisoner said.

“I heard.”

Varney studied Robin, looked him up and down with a curiosity that would have caused offense in almost any other circumstance. Varney’s eyes were large and gray and somewhat protruding. At first his look was fierce, but his attitude softened as a pain struck behind his eyes. Varney thought this young man he was looking at seemed sincere. The youth was tall and blond, wearing a gray hat and a yellow-brown uniform coat with two rows of buttons over a dirty cotton shirt, denim trousers, and boots.

“Well, then, please. Have a look at my nog. Awfully kind of you,” Varney said.

Robin bent over and scraped away the sparse hair around the two lumps, which rose like little purplish volcanoes surrounded by a gray thatched jungle. Blood had dried on the two lumps, but two fresher, deep scratches were oozing on the horse thief’s scalp, high on his forehead. The horse thief’s hair hung down over his ears. He reached up and combed it back with his bloody fingers. Robin smelled whiskey on the horse thief’s breath.

“Santana Leatherwood raked your head with his spurs,” Robin said.

“Pardon?”

“I’m surprised he didn’t yank that earring out of your ear.”

“This earring is protected by a powerful spirit.”

“Do you remember how you got here?”

“I’m starting to, yes, up to a point. I was having a discussion with four Hittites on horseback and suddenly one of them belted me with a club and another whacked me with a shotgun barrel. But I don’t understand why I now find myself chained to a gibbet in this bloody fog.”

The prisoner rolled over, got onto his knees, gathered himself, and stood up. He brushed his clothing with his hands. His knee-length jacket was filthy, bloody, and ripped, but it was expensively tailored. His boots were scuffed and worn but made of fine leather by a master craftsman.

“Have you seen my hat?” Varney asked.

“You weren’t wearing one.”

“My satchel? My dispatch case?”

Robin shrugged.

The prisoner rattled his chain by shaking his leg.

“If I should snap this chain, what next? What lies around us concealed in this fog

“A stockade fence fifteen feet high,” Robin said.

Varney swept the yard with his gaze. He used his imagination to see through the fog and render a picture of his surroundings. He nodded and said, “Well, then.” Varney looked at his chain and at Robin’s chain. “This is quite an unexpected pickle. I must think this situation through. Do you have any tobacco?”

“No.”

A dizziness struck him, and Varney said, “Sitting down sounds a proper idea.” The horse thief traced one hand along the gallows platform until he touched the wooden steps leading up. Varney tugged at his chain and found it was just long enough that he could sit down on the second step. The fog was beginning to fade. A crack of light showed in the east. Varney looked up at the hanging arm of the gallows. He said, “How many souls do you reckon have climbed these steps into the great mystery?”

“None yet. The Yankees just now finished building this gallows. The style in hanging, around here, is from a tree limb.”

Varney touched fingers to his scalp and said, “What is your prognosis for my nog?”

“You’ve had no fracture. You’ll heal.”

“Did you say someone put the spurs to me?”

“Santana Leatherwood left his mark on you. Those are good Mexican spurs.”

The fog was lifting fast, and the late-spring sun began to light the prison yard. Other forms began to emerge as the mist faded away. Men were rising, stretching, spitting in the dirt. Several were pissing against the fence. Varney saw there were about thirty prisoners inside the stockade. Tents and shelters had been erected by the prisoners. Blankets and bundles lay strewed around the perimeter as in an undisciplined military camp. But these were not prisoners of war, Varney saw. They looked to him like robbers, thieves, murderers, drunks, brawlers, degenerates, the failing and fallen. Varney searched with his eyes for the wretch who had been crying out for help, but the voice was silent now. The prison yard was circular, about 75 yards across. The fence posts were pine logs planted in the ground end first, and there were two guard towers and a main gate.

“I don’t see chains on any of the other chaps,” Varney said.

“You and I have been set apart for special treatment.”

Varney’s face lit up with a wide smile that wrinkled the corners of his eyes.

“Then we must become chums,” Varney said. “Edmund Varney is my name.”

Varney wiped his right palm against his chest and then stuck out his hand. Robin was impressed by the strength of the older man’s grip as they shook hands. The name sounded vaguely familiar, but Robin couldn’t recall where he might have heard it.

“Jerod Robin.”

“Tell me, Mr. Robin, why are we in chains?”

“Santana Leatherwood intends to hang us.”

“Good Lord, why me?”

“You for stealing a horse.”

“It was a misunderstanding. My embassy will be contacted.”

“In Texas, horse thieves don’t have any rights, Mr. Varney.”

“Why you? What have you done to be hanged for?”

“I offended Santana Leatherwood.”

“How did you do that?”

“I ran him through with a sword in battle in Tennessee.”

Varney’s white-tufted eyebrows lifted. He scraped a handful of damp dirt and stood up from his seat on the gallows step. He scrubbed his hands with dirt in an effort to remove the dried blood. Varney grinned and said, “Worse and worse. Worse and worse.” He dusted his hands and patted his pockets. He scowled. Varney searched his pockets more carefully. “Gone,” he said. “By damn, it’s gone.”

Robin thought of his letter from Sweetbrush that was sewn into his coat.

Varney bowed his head and pinched the bridge of his nose. The lumps on his head now appeared more like small blue eggs. The spur scars were red but had stopped bleeding. Varney’s shoulders slumped. He shook himself. He raised his head, lifted his chest, and squared his shoulders. Robin was reminded of watching a bare-knuckle boxer who gets up after being knocked down, gathers his wits and his courage, and is game to continue the fight.

“How would I get in touch with this Santana Leatherwood fellow?”

“He’ll be coming to see you soon enough.”

“I am remembering now—the chief of the Hittites. You put a sword through him, eh? How byzantine.”

Varney paced to the end of his chain and back. He scratched the gray bristles on his chin. Varney again studied Robin from boots to hat with a curiosity that would have provoked a brawl if this had been Dutch John’s. To Varney, Robin looked like a prime young Scots-Irish Southerner, a well-reared Celt on his way home from the war.

Varney said, “Clearly you are a soldier.” He paused. “You have the air of an officer.” Varney squinted and sniffed. “You have the look and smell of a horse person. I can tell. I am a horse person myself. So you encountered this Santana Leatherwood in a skirmish and thrust him through?”

“It was more than a skirmish,” Robin said.

“A battle then. What was it called?”

“Snow Hill.”

“I haven’t heard of it. When was this battle?”

“Last Christmas Eve.”

“In Tennessee, you say?”

“In the Great Smoky Mountains, along the North Carolina border.”

“You were in a backwater affair. The battle at Nashville ended in the middle of December. Sherman had gone from Tennessee long before Christmas Eve. The major fighting had moved toward the sea. With respect, Snow Hill must have been a skirmish.”

“I was at Nashville. Then we went east to the mountains. That’s where Snow Hill is. We judged our fights by how nasty they were,” Robin said. “It was a battle.”

“I do understand about war, old son,” Varney said. “I did a career turn for Her Majesty’s horse soldiers and the East India Company in India and Afghanistan in my younger days that were not so long ago, it seems to me.”

“Is that what you call hell?” asked Robin.

“India and Afghanistan were merely a warm-up for the real thing. But I do accept your definition of battle. Snow Hill was a battle that I never heard of. Am I correct in assuming you are going to tell me about it?”

“No.”

“Later, perhaps?”

“I don’t see us having a later,” Robin said.

“Last Christmas Eve you nearly slew the Hittite?”

“Nearly.”

Varney paused and smiled at a memory.

“I was in Spain last Christmas Eve,” mused Varney. “While you were fighting the Hittite, I was in a cave in the Pyrenees.”

“You get around,” Robin said.

“Indeed.”

Varney yawned. He drew in a deep breath. Robin noticed the creases in Varney’s forehead and between his brows. From what Robin knew of London from stories his mother told and from books in the library at Sweetbrush, he speculated that Varney might be a highborn confidence man fleeing from a serious misadventure back home.

They heard the cry “Bastards coming!”

Around the yard, prisoners turned their heads to hide the identity of voices that began yelling, “Bastards coming!” The fog had thinned away. In Texas in June, the weather could change quickly from cool, wet, and green to hot, yellow, and dry. A guard in a blue 7th Cavalry uniform raised the bar and pulled open the main gate. Little bowlegged Billy Leatherwood entered carrying a scattergun that almost reached his chin. He stopped and spoke to the guard and pointed toward Robin and Varney. Robin could see that Billy had tied around his neck a red bandanna like those worn by his brothers in the collaborator Home Guard Company.

“Liiittle bastaaaaard comiiing!” a voice whinnied like a mule.

“You think that’s funny? Using that kind of language?” shouted Billy Leatherwood.

The Englishman said, “There’s something familiar about that bandy-legged chap.”

“He’s one of your Hittites. Coming for us.”

“Ah, yes.” Varney raised an eyebrow and said, “Into the crucible then. I do wish I had my hat.”

Chapter Three

The three Leatherwood brothers, wearing their red neckerchiefs that marked them in Robin’s eyes as traitors, marched the two prisoners, both still dragging ankle chains, through the gate of the stockade and headed toward town on a road called Pine Street. Behind them to the west lay two miles of forest and streams that ended on the east bank of the Colorado River. Beyond the river rose white limestone cliffs and green hills.

“This is your lucky day,” Billy said to the prisoners. “The county judge has swum the river on horseback so he could get here to hold court first thing this morning. You’re lucky to be brought up before a real judge in these lawless times. Lieutenant Tom Custer will be in court in person to get a firsthand look at what kind of stupid idiot would try to steal his horse. His brother, General Custer himself, will be showing up here in Austin with the rest of his regiment in a few days, Uncle Santana says. Too bad you fellows will be dead by then. You, Robin, you would be thrilled to see the 7th Cavalry riding into the capital of Texas with their flags and bugles and drums.”

Billy laughed.

“Be a good chap and let me have a drink of water?” asked Varney.

“Got none to spare,” Billy said.

They walked past young boys fishing in Shoal Creek. The creek was wide and flowing from the wet spring. The boys kept a cautious distance between where they stood with their cane poles and the position of four blue-jacketed federal troopers who were watering their horses. Farther up the creek was a gathering of tents, and more federals were walking about. The boys and the soldiers stared at the procession going past, as the Home Guard marched the prisoners toward court. One of the fishing boys hooted and yelled at the Leatherwoods, “Red-throat sons of bitches.” Two rebel soldiers, looking haunted and hungry, sat beneath an oak tree and watched without interest as the prisoners went past. The soldiers had already seen the worst of nature. The Leatherwood brothers fell into a proud step, as if they could hear a military drummer. They had avoided serving in the military, but they enjoyed playing soldier. Luther poked Robin in the ribs with the knobby club he had used to lay out the Englishman.

Luther said, “Step smart there, Jerod Robin.”

“I’m keeping score, Luther,” said Robin. “Every time you touch me goes into my ledger to be repaid.”

Luther whacked him on the back with the club and knocked a puff of dust out of Robin’s coat.

“Be sure and don’t forget that one,” Luther said.

Varney rubbed his throat and looked at Billy’s water bottle. During his three days in Austin, Varney had observed the mood of the town to be taken over by that old devil fear. Citizens who had opposed the war had lived for four years with the cold comfort of their consciences and their reasons, and they still feared the night riders who burned the homes of Unionists. Already, Varney knew, the winners had begun satisfying their need for revenge. Anyone might be a target. From his window in the Avenue Hotel, on Congress Avenue, Varney had heard shootings. Grudges were being settled without honor. The sounds of shouting and brawling were frequent interruptions in the nights. A fog of anxiety hung over the town. Varney enjoyed the sensations of this kind of place. The tensions reminded him of Kabul.

They saw an old man staggering across the road, bent by the weight of three saddles that he carried on his back. The saddles were tied together with a rope that stretched across the old man’s forehead. Varney wondered if he had stolen the saddles, or was he hurrying along to hide them from thieves? Daylight robberies were common. There was randomness to life. Half a dozen girls in spring dresses stood inside a picket fence and watched the prisoners being marched east on Pine Street. A large Georgian house with white columns rose among the trees on a hill behind the girls. The house reminded Robin of his home at Sweetbrush. One of the girls cried, “You stupid red throats, you dirty Judases.”

Robin smiled at the girls and waved to them.

“They hate you Leatherwoods,” Robin said.

“They’re just a bunch of trash. What do I care about them?” said Billy.

“They whores,” Adam said.

“They’re not whores. Just trashy Austin girls,” said Billy.

“No, they whores with smelly, swampy cooters,” Luther said.

The Leatherwood brothers whooped.

“Cooters,” Adam yelled at the girls. “Swampy cooters.”

“I wonder if I might have a nip from that water bag?” the Englishman said.

Robin looked around at the scowl that was pinching Varney’s face. If Varney had been drinking at Dutch John’s until he tried to steal Custer’s brother’s horse in the middle of the night, he couldn’t have had any sleep except for the time he was unconscious, and that would not have been restful. Varney licked his lips. He was trying to decide which headache hurt the worst. He had the sick headache that follows from the poison of too much whiskey. He had the pulsing headache that came from the blows to his skull by the Leatherwood brothers and their uncle. But topsies among his problems was this awful thirst. He must have water. He thought of his journey across the plains of Punjab the summer when even the bloody camels were suffering. This morning was no topsies for that ordeal, but he could feel last night’s alcohol drying and shrinking his tissues. His body’s cry for water was more urgent than the hurt of a few more lumps on a head that had already taken so many.

“I’m saying, friend, what about a tug at that bag of water?” said Varney.

“Don’t give him nothing, Billy,” Luther said.

“We can’t be stopping. The judge gets mean if you make him wait,” said Billy.

Robin saw a small shudder go down to Varney’s boots. He wondered how a man like Varney, obviously educated and claiming a military background, had found himself accused of stealing a horse in Texas. Robin knew quite a lot about England from his parents—his father had sailed to London and married his mother there—and from books in the library at Sweetbrush. During his two years at Austin College, in Huntsville, Robin was reading for a history degree. For nine months of the year before the war, Robin came home and taught at the two-room, white-pine school his father, Dr. Junius Robin, had built for the children of the workers—slaves and Mexicans—at Sweetbrush. Soon after Dr. Robin had opened the school, young people had begun coming down the red-dirt roads from other farms and plantations, along with the children of property owners and merchants who did business in the town of Gethsemane, four miles through the forest by road but closer by boat on Big Neck Bayou. By the time young Robin returned from college to help his family at Sweetbrush and took over teaching school three mornings a week, there were from ten to forty pupils, Negro, Mexican, and white, in class, depending on the season. The Leatherwoods lived in a two-story house near the church in town. Pastor Horry Leatherwood, their father, the mayor of Gethsemane, sent his three sons to the Sweetbrush school even though he had become an enemy of young Robin’s father, the doctor. Adam and Luther would sprawl spraddle-legged in their cane chairs in class and listen to Jerod Robin with dull-eyed distaste, but little Billy was fascinated when Robin told them about British history, about the Magna Carta and the Crusades and the two American wars of revolution in the past eighty years against British colonial rule and the abuses of royalty. In particular, Billy had loved stories about the Crusades.

“I’m asking you one more time for water,” said Varney.

“Or you’ll what?” Adam said.

“I hate Englishmen,” said Luther. “Give me a look and I’ll bash you.”

“I’ll do it again, twice as hard,” Adam said.

Billy said, “My favorite Englishman is Ivanhoe.”

This was unexpected news to Robin. He had not taught Sir Walter Scott at the Sweetbrush school. Robin remembered Billy bent over a book on English history, slowly picking out each word and forming it in his mind to grasp and keep it. Later Robin discovered Billy had torn out the chapter on knights and the code of chivalry and had taken it with him when he ran away into the forest. Now Robin wondered if Billy might have slipped in and stolen Ivanhoe from the Sweetbrush library.

Billy said, “I like how Ivanhoe whipped that Boy Gilbert and rescued the beautiful Jew girl.”

“Bois-Guilbert?” asked Varney.

“ ‘Boy Gilbert’ is how you say it,” Billy said. “This ain’t France.”

“You are a fancier of romances, are you?” said Varney.

“Of what?”

“Of romantic novels.”

“Not that crap. No,” Billy said. “I don’t have time to waste on imaginary stories. I like to study the real English history. You ask Captain Robin if I don’t.”

“It’s true,” said Robin. “Billy is a great admirer of the Crusades.”

“I wish they would have another Crusade. I’d sign right up,” Billy said.

“You’re eager to kill Muslims?” said Varney.

“I’ll kill whatever they got over there,” Billy said.

Robin was watching all along the road for any intervention of luck or fate that would give him a chance to grab Billy’s shotgun and turn the weapon on the Leatherwoods. Robin could not flee because of the chain that locked him onto the chain of the Englishman. Sweat rolled down his chest inside his butternut coat. He could feel the letter from Sweetbrush against his heart.

“So to you Ivanhoe is an historical figure?” Varney said.

“What do you mean?” said Billy.

Varney’s tufted eyebrows lifted, and furrows trotted across his brow.

“I am a great admirer of Wilfred of Ivanhoe, just as you are,” Varney said. “Yes, I am a fan of Ivanhoe, indeed. Powerful chap. Handsome. Fearless. He fought in the Crusades against the Arabs beside Richard the Lionheart. Am I correct?”

“That’s right,” Billy said.

“Tell me if I am correct that Ivanhoe returned from the Holy Land to England and was betrayed and taken prisoner by the Norman barons. His friend Robin Hood helped him escape, if I recall the story truly.”

“You know your history,” Billy nodded.

Varney said, “The mysterious Black Knight appeared at the jousts as the champion of the beautiful prisoner Rebecca and in fair combat killed Sir Brian de Boy Gilbert, thus saving Rebecca’s life.”

Billy was excited. “Boy Gilbert was going to burn the Jew girl at the stake. But the Black Knight knocked him around and then stood over his hacked-up body. The Black Knight took off his helmet and it was Ivanhoe underneath. Ivanhoe looked at the damsel and told her to take her old Hebrew daddy and go back where they come from. He didn’t even rape her.”

“That was stupid of him,” said Luther.

“She was what is known in history as a damsel. He was a knight. Why the hell you think they called him Sir Ivanhoe? He don’t rape damsels,” Billy said.

“He’s really stupid, then,” said Luther.

“Who ever heard of a Jew damsel?” Adam said.

Varney said, “Wilfred of Ivanhoe always kept his prisoners well supplied with water. It was known by all. Even the Arabs in the Holy Land knew it—that if you were nabbed by Ivanhoe, you would never die of thirst. He might throw you off a castle parapet, but a man of great heart and humanity like Ivanhoe would never withhold water from a prisoner.”

“He’s making fun of you, Billy,” said Adam.

“No, he ain’t,” Billy said. “That’s the kind of fellow Ivanhoe was.”

Billy unhooked the goatskin bag of water from his belt and passed it to Varney, who emptied it with three gulps. Robin’s tongue touched his lips unbidden, but he would not ask the Leatherwoods for any favors.

“Where’s your uncle?” Robin said.

“He’s somewhere oiling up a new rope just for you,” said Luther.

“You shouldn’t of stobbed him. He was hurt real bad for a while. He almost died,” Adam said. “If you was going to stob him with your sword, you should of stobbed him good and killed him dead. Uncle Santana don’t forget, and he sure as hell don’t forgive.”

“He’s got a huge dent now where his right kidney used to be,” said Luther.

“He keeps his shirt on when he takes the ladies to bed,” Adam said.

“And he does lots of that,” said Luther.

“Not as much as he used to,” Adam said.

Varney gave the water bag back to Billy and said, “Thank you. This earns you a shiny gold star in heaven.”

“I’ve already got my ticket to heaven. Our daddy is a preacher. He keeps us prayed up and ready to go. But I ain’t ready to go just yet,” said Billy. “You prisoners step smart now. People are watching. You don’t want to look sloppy or scared.”

The odd little procession crossed West Avenue and passed into the heart of the town. Here in Texas they called it the capital city, but to Varney it was a small town. Several boys fell in behind and marched along, kicking up dust, mocking the prisoners and the red-throated Home Guards. The procession turned north on Colorado Street, walked a few minutes to Mesquite Street, and then turned east again. Swallows flitted overhead. The birds were making nests on the limestone walls of the old capitol. Pigeons ruffed up their feathers and strutted and cooed. At dusk, clouds of bats would fly out from the building. Men peered into the morning from doors and windows of saloons. In front of a Methodist church built of pine logs, a flea market was spread across the grass. Robin’s eyes searched the faces, hoping to find an ally who might help him escape. But the people were involved with their own daily despairs and turned away from the spectacle of three Home Guards marching two chained prisoners to confront their fate.