The Panhandle, Texas’ Siberia. Misunderstood and unloved, it is an unlovely hinterland best suited for pioneers or pariahs. Nature gave it few trees, no visible water, and animals and plants as unhospitable as the terrain; then a handful of humanity happened along and added industry that was smelly, messy, and hard. The Panhandle is bleak, lonely, and far away, and it is my favorite part of Texas.

I was born there, true, in Pampa. I’ve taken my share of guff about my hick upbringing and have even bemoaned it myself. But despite it all, my childhood memories remain untarnished. Growing up in the Panhandle meant running free. There were countless creek bottoms, mesas, gullies, prairies, and oil leases to roam and explore. My sisters and brother and I had an abundance of and a fascination for everything, animal, vegetable, or mineral. The Panhandle lacks a lot in the cultural and social departments, but it was the best place in the world to be a kid.

As I grew older, though, the Panhandle began to seem small-time. It was the sort of place that a newly hatched adult, her head full of worldly aspirations, could not abide. I moved to the city and made a life there, but in the seventeen years I have been away, the Panhandle has haunted me. Finally, after years of journeying back and forth to visit my family, I made up my mind to call on a sampling of Panhandle types—farmers, cowboys, oilmen, and such—to compare the reality of their day-to-day lives with my childhood impressions. Only as I’ve grown older and begun my own family have I felt the need to take a serious look at the place or to know the people who, unlike me, decided to stay.

The Top O’ Texas

The Panhandle has 26 counties. (Some say 32, but the region is square, not rectangular. Sorry, Littlefield, Plainview, and Muleshoe.) It has some 390,000 people in 26,000 square miles, or 2 percent of Texans in 10 percent of Texas. It is embroidered with all the classic Texas details: cowboys, cattle, oil and gas, wilderness, western-movie panoramas. Yet for all its typical Texanness, the Panhandle’s inhabitants keep not only a physical but also a mental distance from their more sophisticated counterparts downstate. The Panhandle is closer in distance and in spirit to the capitals of Oklahoma, Colorado, and New Mexico than to Austin.

Except for Amarillo there are no cities, only small towns where kids on bikes deliver the paper, Coke machines dispense bottles, and water towers bear the names of the local high school teams. Here you can cash a check without an I.D. and dial only the last five digits of phone numbers. (My parents recall in 1954 when DeLea Vickers, a Pampa pioneer, fumed about the newfangled dialing because he had to give up his longtime phone number, 1.)

Pampa was, of course, the first stop on my nostalgia tour. The constants were still there: the rodeo grounds, the red-brick streets, the Santa Fe rail yard where we had played on the handcar and mashed pennies on the tracks. But a bank has supplanted the hospital where I was born. The Woolworth’s where I did my Christmas shopping for a decade was now a furniture store. And Caldwell’s, the favored drive-in of my day, long ago fell victim to a Burger King.

Landmarks aside, Pampa has little to do with my memories. The country held all the romance. We chased down tiny horny toads the size of a man’s thumbnail and caged them in matchboxes until someone took pity on them and set them free. We had one as a pet once, Horatio, whom we housed in a shoe box and kept alive until the tragic day he was dispatched by his own dinner of red ants. Another pet was Cowboy, a tarantula so named for his bowlegged stance. He occasionally broke free of his pickle jar and terrorized my mother’s bridge club.

And, naturally, we had the weather. The dryness of the climate gave us a lifelong appreciation for rain, and in wet weather we danced about outside till we were soaked. The unceasing wind never bothered us, and coming from the right direction, it could be relied upon to provide one heck of a swing ride. At night while it whined we told ghost stories in our bunk beds. If the wind picked up during the day, Mother would pin quilts to the clothesline, and we would huddle in this makeshift cabin and pretend we were hardy pioneers. Sometimes the sky would turn a weird yellow, and a sandstorm would fling tiny needles right through the walls and eventually bring the whole playhouse tumbling down. Then we pioneers would make a break for the back door, where just inside we would pour a cup or two of grit out of our shoes before Mother would let us all the way in.

We took regular Sunday drives, begging Daddy to drive through the dust devils. At farms and truck stops we examined the selection of insects smashed on the machinery grills. We deciphered the brands on ranch gates—Rocking Chair was our favorite—and made up names for our own imaginary spreads, like the Buzzard Slump, with its brand of a backward, sloping S. We went rock hunting and prized as an arrowhead any piece of flint that was roughly triangular. We had contests to see which team of two could count the most pump jacks on its side of the road. Occasionally, we would stop where an elevated gas pipeline spanned a gully, and we would cross it, balancing with our arms like the Great Wallendas.

Our favorite picnic spot was Black Widow Bottom, a little clearing near Lefors where a huge cottonwood always contained two or three of the title characters in its giant knothole. We took turns perching on the limb nearest the knothole and gazing, mesmerized, at that evil sorority with their swollen egg cases and gleaming legs and menacing red hourglass bodies. When we finally tired of watching the spiders, we played in the creekbed, which joins the North Fork of the Red River. The bed was always bone-dry, leaving a jigsaw puzzle of dried mud that provided palm-size pieces just right for flinging at a cow. On the way home we urged Daddy to catch up with the water mirages.

When I was in high school, my friends and I headed out of town in any direction until we found a suitably deserted oil lease track or farm-to-market road. There we would pull out our smuggled alcohol and sample it in peace; if need be, we had plenty of time to hide the evidence because we could spot headlights two miles away.

Two of our favorite hangouts were near Bowers City, ten miles from Pampa. One had its own legend, something involving a murder, a grave, and a hanging tree. The boys raced each other down the cliff while the girls oohed appreciatively. The second place was an Amoco lease, or, as we knew it, Screaming Wells, a deep crack of a gully whose banks were dotted with pumping units. When the wind cranked up and whistled across the empty standpipe, it made an unearthly screech and gave us good reason to cuddle closer.

Being scared was a big part of our nighttime adventures. We shivered when an owl hooted or the brush rustled. The wind—there was always wind—brought with it the faint reek of chemicals or cows and the eerie, rhythmic creak of machinery. One friend of mine, while parking with her boyfriend on a deserted road, turned on the headlights to discover strung up on the fence in front of them a long row of coyote carcasses. Maybe that’s why she graduated a semester early and headed to UT.

The Breaks

Nature is not friendly, and the Panhandle is composed mostly of nature. The sun blazes, buzzards circle, stickers lie in wait. The most rugged region is along the Canadian River, where the land breaks up into bleak caliche hills, eroded red clay cliffs, and myriad small canyons that turn in upon themselves like braids—the Canadian breaks. The ground is impossibly rough, bearing nothing more decorative than cholla skeletons and bleached slabs of dolomite.

Yet for all their inhospitality, the breaks were inhabited long before the rest of the Panhandle. On private land eight miles off U.S. Highway 385, in Oldham County, is Landergin Mesa, an Indian high rise 160 feet above the Ranch Creek feeder of the Canadian River. Atop the mesa, beginning about the year 1100, peaceful Indians built stone homes, perhaps ninety of them, overlooking the river. Below, on the fertile banks, they grew corn, beans, squash, and tobacco to supplement their buffalo meat and other game.

Landergin Mesa is a national historic landmark, and touring it requires an official guide. Bill Harrison, born in Canyon fifty years ago, is now the curator of archeology at the Panhandle Plains Museum in Canyon. “Kept leaving,” he said. “Kept coming back. Finally stayed.” Bill has tousled gray hair, boots that have earned their keep, and a fearless driving technique. The day of our trip to the ruins, the dirt road was gluey from recent rains. After a couple of miles, we turned off onto land used so infrequently that my city eyes failed to discern the track. At a gaping creekbed Bill switched the pickup to four-wheel-drive, and we jangled across, leaving ruts you could lose a cat in. “This isn’t bad,” Bill said.

As we drew closer to the mesa and farther from anything resembling humanity the ruts got deeper and uglier until finally, in a stand of cottonwoods, Bill said, “We’ll whoa it right here.” The mesa was perhaps half a mile away, imposing even at that distance. We picked our way through the cactus to the base of the trail that led to the mesa top. It had taken archeologists two and a half months to establish the path, which twists and turns up the least-sheer face of the cliff, instilling an appreciation for the agility of the people who used to dash up and down it.

We hadn’t gone a dozen paces when Bill halted and bent to pick up something: an arrow point. He showed it to me and then, to my surprise, threw it back down. Then he spotted a sidescraper, an obsidian flake, and a piece of pottery. He tossed them all back into the brush. “Just Indian litter,” he said.

Having conquered the mesa, we were almost beaten back by the wind. It was a relatively mild fifteen miles per hour, but the keening was continuous. The only other sound was a crow’s calling far away. Besides the little white speck of Bill’s pickup, the only signs of human habitation were under our feet.

Most of the stone homes, crowded shoulder to shoulder like rush-hour bus riders, were half subterranean. Dolomite slabs were embedded as a foundation, then built up with adobe that is long gone. Low entrances required a visitor to kneel and crawl in, allowing the occupant a chance to let loose arrows in case the visitor happened to be unfriendly. The mesa was perfect for defense; it afforded a view of the country for miles. The top, not much more than an acre, was shared by some two hundred people willing to accept cramped living quarters and a punishing wind in exchange for a 360-degree view of the horizon.

A huge anvil of a thunderhead was building up to the south, so Bill and I decided to escape before our road washed out completely. In two hours we had traveled eight hundred years in time.

Call of the Canyon

For 12,000 years the Palo Duro has been the Panhandle’s only tourist attraction. It is not such a grand canyon, but it is impressive enough, carved some 1,200 feet deep by the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River. Like the river, the canyon is red, and rusty red of the fan-shaped lower slopes called the Spanish Skirts. For tens of centuries, Indians ate the canyon’s arrowroot, prickly pears, acorns, and smorgasbord of game; they relied on the dark green juniper that carpeted the canyon (the hard wood that gave the Palo Duro its name) and hid in its caves and gullies from the sun, the wind, and the white man. It was their last holdout on the plains and the scene of their inevitable defeat.

To kids from Pampa, the Palo Duro was a common but beloved field trip; we had fun in the name of education, hunting for devil’s-claws, or unicorn plants (black, scaly, shrimplike pods), and desert roses (roseate gypsum in crystallized blossoms). But the real lover of the canyon is the scientist. I persuaded Jack T. Hughes, a professor at West Texas State University in Canyon, to read to me from the Palo Duro’s open book. He identified strata and shrubbery that hid the fossils of horses, rhinos, and dinosaurs. He pointed to huge boulders full of holes used as mortars by countless generations of squaws.

At a low wash Jack stopped, rock hammer ready, and led the way up a cliff. “Be careful,” he said. “Trying to get a footing on those slopes is like trying to stand on a tin roof covered with marbles.” He skirted a sinkhole, a huge black maw in the ground that smelled like a dungeon. He risked such dangers to look for geodes and celestite, a pretty blue stone that, like manganese, is common in the canyon but rare elsewhere. He crushed a soft slice of gypsum, the white lace that bands the Spanish Skirt, and identified strips of agate and nodules of red hematite in various chunks of stone. Jack spoke of the Miocene, Pliocene, and Pleistocene epochs and then, pausing by a beer bottle, remarked, “And that’s from the Obscene Age.”

We huffed and puffed up one slope to find some of what Jack calls the local opal, a commercially valueless but pretty bluish-white stone that runs in layers between other rocks. On the way he stopped to ogle a smooth piece of dolomite on which was imprinted a small three-toed foot made by some odd creature of yore on a casual stroll. “That’s pretty nice,” Jack said. “We should have that in the museum.” He chewed on the sweet hulls of mesquite beans and continued his geologic love talk: “Here are some beautiful mud cracks. Now this is your very, very vuggy opaline chert.” But I was only half listening; I was back with the ancient beast that had trodden on a muddy patch of ground and left his own graffiti.

Tiller of the Soil

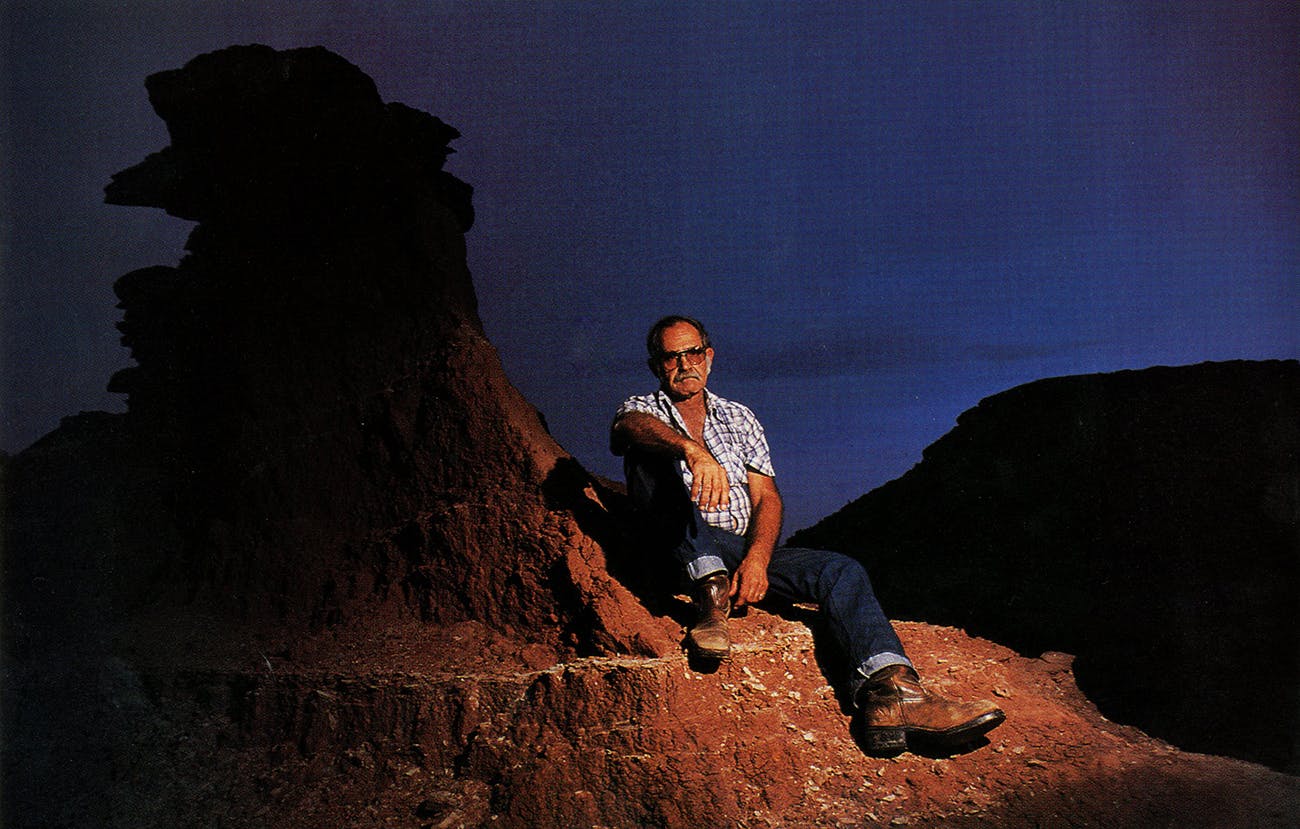

Charlie Bowers, a ruddy, genial man, raises corn, wheat, and milo on four thousand acres sixteen miles south of Pampa, in the same place where he was born and raised. Actually, he has farmed for only fifteen years. Though his father was a farmer and both grandfathers too, Charlie never planned to be one. But when his father died, Charlie, who was off at Texas Tech, came home to help his mother with the harvest. When he finished college, he rejoined her, and even after her death Charlie, hooked on the land, remained on the family farm in his parents’ house. I talked to him there, interrupted occasionally by the crackle of the two-way radio that is the farmer’s telephone.

“Farming is a misunderstood profession,” Charlie said. “No one in an urban place has any idea how technical our industry has become.” He refers to the varieties of grain, the fertilizers and pesticides, and the equipment. A tractor, for example, may set a farmer back $80,000. “The only thing that’s the same now is that they’ve still got a steering wheel, a seat, four tires, and a motor. They’re so comfortable—and air-conditioned. You’re really roughing it out there on that air-conditioned tractor.”

“Of course,” interjected his wife, Janyth, “sometimes you’re on it fourteen hours a day.”

Charlie owns a section and a half, 960 acres, of the land he farms. He employs a local high-school kid part time and one hand full time. The three of them plant, harvest, repair, plow, fertilize, and irrigate, sometimes working until ten at night. “My father always said you can stay in farming longer and stay broke longer than in any other business,” Charlie said. “I don’t mind being in debt as long as I can see if I’m progressing.”

The work didn’t stop while I was there. Charlie had to check some irrigation pipe in a cornfield and invited me to go along. We climbed into his pickup—I think, under all that dust, it was white—and from my window I had the classic car-seat view of the Panhandle: grain fields, a perfectly matched set on either side of the road. As we headed down narrow dirt roads he showed me a stubble-mulched field and a tilled one, a sweep plow and the more common disc variety. He pointed out the two methods of irrigation in the Panhandle, pipe and sprinkler. Like about half the farmers here, Charlie uses the Ogallala Aquifer by gas-powered wells; electronic sprinklers are more efficient but far more expensive to install.

Cost is measured another way too. The aquifer that took thousands of years to fill is being sucked dry by a farming practice that has existed only since 1909. “They thought the oil and gas decline was big,” Charlie said. “When this area runs out of water, you might as well pack it up and leave.”

At the field Charlie let the truck idle, ignoring the hand brake; the land is so flat that there was no danger it would roll. His work that afternoon consisted of pulling on oversized plastic boots and wading down the swampy edge of the field to turn off eighty-odd valves on the irrigation pipe. A farmer has a serious acquaintance with mud; Charlie’s boots doubled in size by the time he was ten rows down. “Irrigation is three times the work of dryland farming,” he hollered over the rush of the water. “I spend more time walking and irrigating than anything else.” He disappeared into the cornstalks, boots squooshing loudly. I sat on the tailgate. All around me, taller than the pickup, loomed corn; I felt like Dorothy in the poppy fields, threatened not by sleep but by sneezes from the ubiquitous pollen.

Charlie returned, switched to dry boots, and drove me around the rest of his land. He talked about weather, the unknown quotient in farming. “You can lose a crop so quick. You get every kind of weather here but a hurricane. But the weather can help you too. Sometimes a good rain helps your insect problem as much as anything.” Once, rain stunted his maize, but another time, it hit the corn at exactly the right time and produced a lot of double ears. A farmer raises a mixture of crops to hedge his bets. “I’d like to blame it all on the weather,” Charlie added. “I’ve made my share of mistakes. But never twice. Your memory is in your pocketbook.”

We drove on. He pointed out maize that was “heading out” and cut open a stalk of struggling milo to show me the swirl, the tightly furled grain head inside. He took me to the catch pond, or tailwater pit, which collects draining irrigation water for reuse. He stopped the pickup, and we sat for a minute, gazing out over the sea of corn.

“When something goes wrong,” Charlie said, “you wonder why. Farming is hard on your religion. But anybody who farms has got to be religious. You may not beat a path to church every Sunday, but if you don’t talk to the Lord, you’re kidding yourself.

“Of course, the Lord deals you what you can handle. He never gives you a card you can’t play.”

Cowboyin’

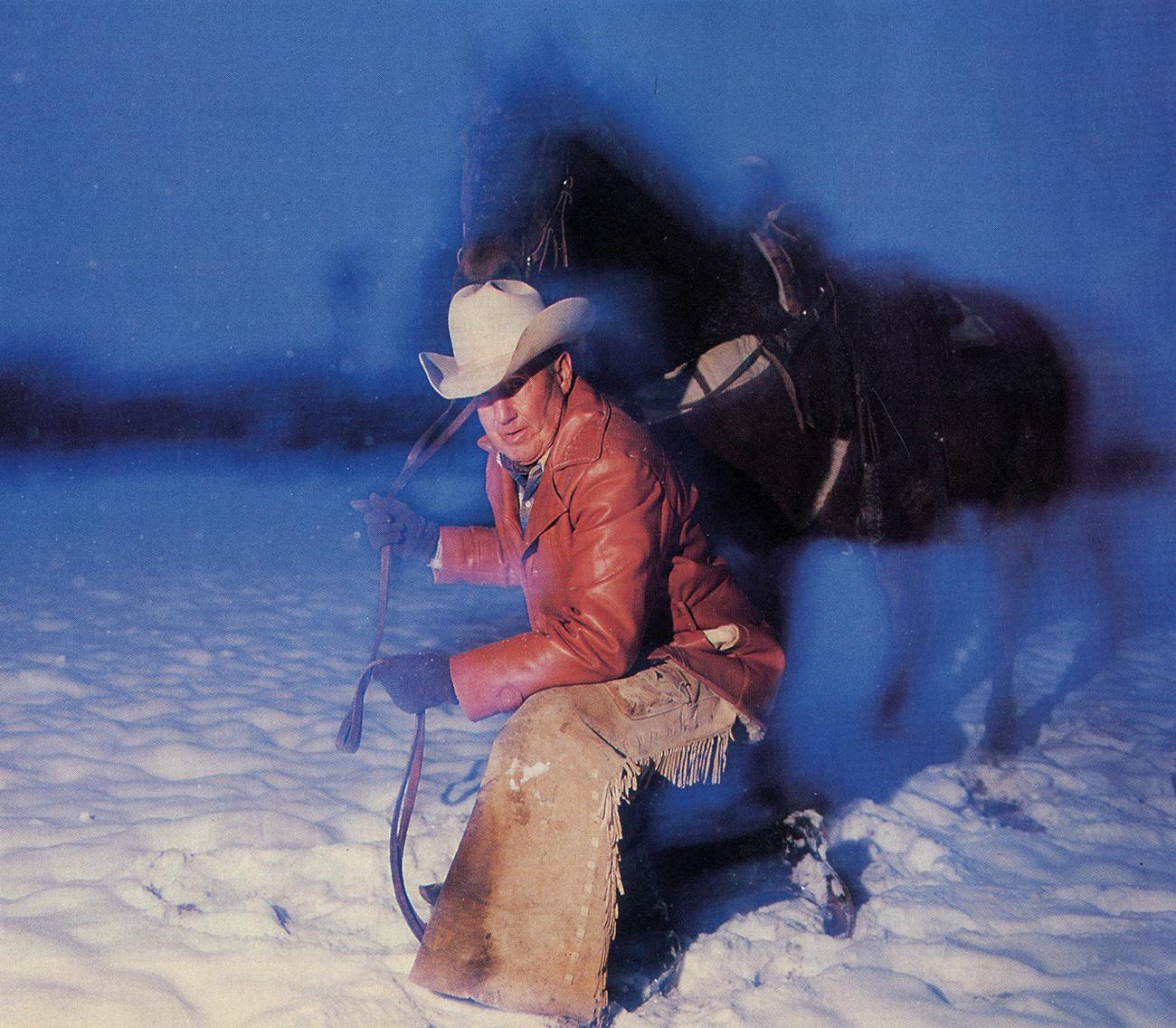

With its grass and cattle and range, the Panhandle is one of the last bastions for the cowboy. I’ve always felt proud to be from cowboy country, yet I had never so much as talked to one. Sitting in Lefors in an all-too-rare patch of shade, surrounded by horse pens, was Tooter Henry, one of the old breed. He was wearing all the right garb: a cowboy hat and boots, a Western shirt, jeans, and a latigo belt. His face resembled well- treated leather. He frittered twigs with his pocketknife. Nearby was an old chuck box spilling out gloves, rope, bits, and horseshoes and a saddle rack decorated with saddles, chaps, deer antlers with shreds of flesh still attached, and cans of Anchor Horse Spray and Rub-On insect repellent.

“Ma’am,” Tooter said, “all I’ve ever done is cowboy. I trade horses, and I break ’em and such. I just do ranch work. I been here a long time.” He has: 52 years, since he was nineteen. By age twelve Tooter—no one ever calls him by his given name, Clyde—had traded five hundred marbles for his first horse. He left school, and from then on horses were his life. His first jobs were on the huge ranches of the day, like the Hay Hook (“There were sixty sections of that devil”), where he stayed for forty years. “We’d gather cattle, brand ’em, dehorn ’em, feed ’em in the winter. We fixed windmills and built fence. We’d leave the ranch house about eight and not have a bite all day. Today it’s an altogether different deal,” he said. “You can feed ’em faster out of a pickup than a wagon, and you don’t need the men you used to. Nowadays there ain’t one guy out of twenty that’d know how to hook up a team.

“You never did make much on these old ranches. Maybe thirty dollars a month. And it wasn’t any eight or ten hours either. It was dark to dark, and if it got late of an evening and there was something to do, you did it. But work wasn’t work if you liked to do it.” Tooter made extra cash breaking horses for $5. At 71 he’s still at it, now commanding $300 a head. He also has about twenty horses of his own.

It was late afternoon, and Tooter’s twenty acres were alive with the whinnying of horses reunited for the evening. He and his wife, Lois, a childhood playmate, have lived here in their white frame house for 23 years. Tooter interspersed recollections with instructions to his hired hand: “Raymond, give the little one some of that alfalfa.” Lois came out of the house, past the donkey wagon full of flowers and the gate arch graced by a crumbling plaster cowgirl. “Mama,” he called, “come sit down with us over here.” After a spell he unfolded himself and took me on a tour of his property. The horses were dining on hay—all but a frisky colt who insolently flicked his tail at us.

It was hot in the sun, so we retired to the kitchen, where Mrs. Henry poured some sweetened iced tea. I discovered from the framed pictures on the wall that Tooter had been a rodeo performer of some note. He was too modest to bring it up himself. “Yes, ma’am,” he said. “I rodeoed a lot. My first one, I was about fifteen, mostly just helpin’ out around the chute or as pickup. But I roped. That was what I did best.”

In many of the photographs a younger, whippy Tooter appears on the same gray horse. “Bally Sox,” Tooter said with pride. “My favorite old horse. I give two hundred for him and his mother. Sold her for two and a quarter. He was a fine old boy. Two fellers offered me twenty-five hundred for him once, but I wouldn’t sell.”

It was suppertime for cowboys as well as horses. Tooter walked me outside. The air smelled of liniment and fresh hay. Raymond moved a horse or two out of the path of my car. “Come back,” Tooter called as I drove away. “You don’t have to be workin’. Just come on back anytime.”

Grass Roots

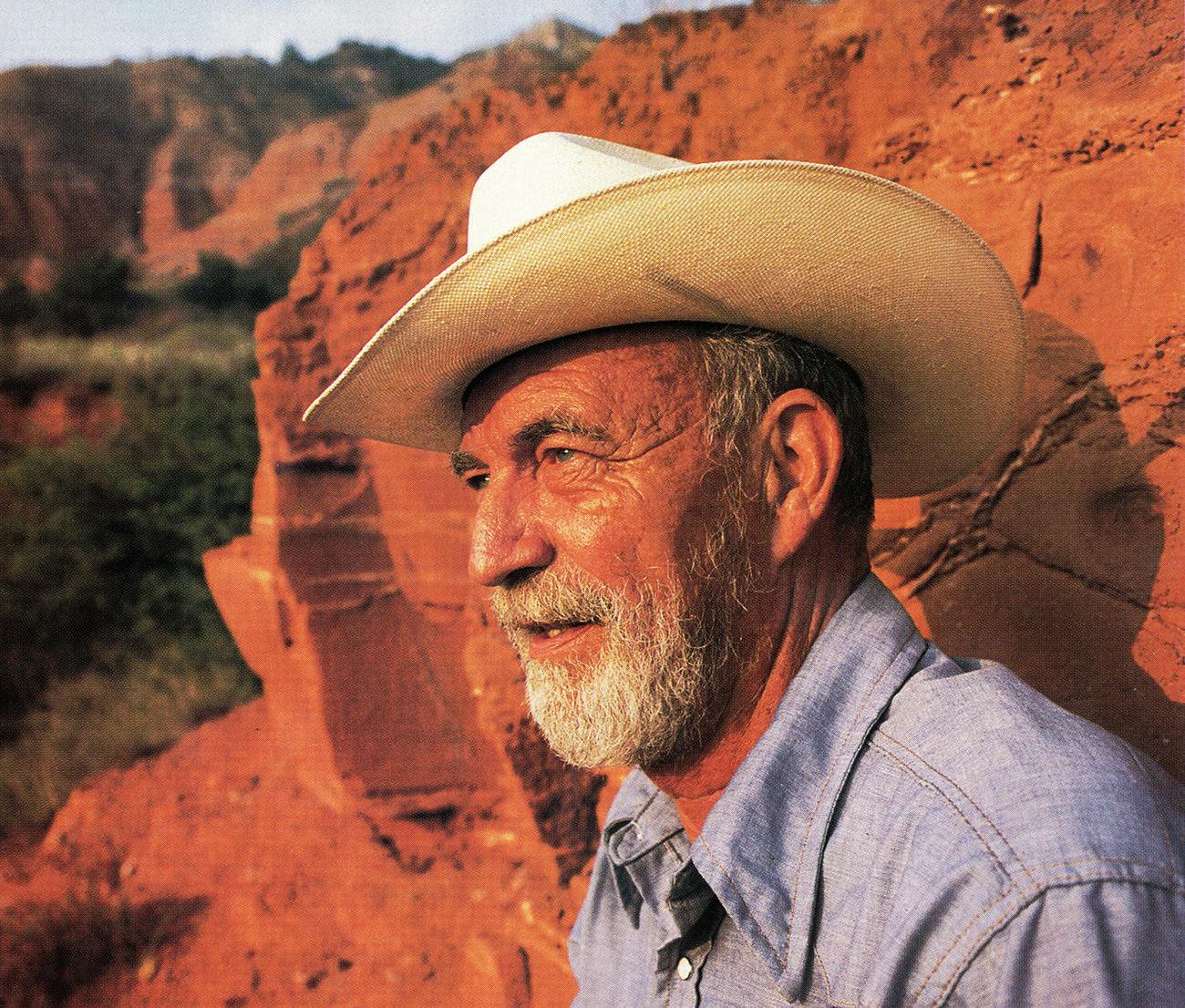

“I don’t work on Sunday,” H. Joe Franklin told me, “but I don’t mind if you do.” A likable man with a road map of laugh lines around his eyes, Joe sometimes runs as many as a thousand head under the Flying Cross F brand on the fourteen sections of land that his family has owned for fifty years. That’s about nine thousand acres of ranchland—“a big ranch to someone living in downtown L.A.,” Joe said, “but small by Texas standards.” His father, a veterinarian, purchased the land with the proceeds from his serum for blackleg, a fatal cattle disease. Today the Franklin vaccine is used everywhere, and blackleg is no longer a threat.

Joe has worked on the ranch all his life. He raises yearlings, which are less trouble than cows and calves. His cattle are what he calls “number one Okies,” mixed breeds with a mishmash of characteristics. Sometimes their ancestry is recognizable, and they are identified by the breed they most favor: “That Hereford is kind of dumpy and small. That Charolais is more like what we want.” A rancher’s goal is to fatten his cattle. “You keep feedin’ ’em, or you sell ’em, whichever your banker votes,” Joe said. “It’s not hard, this business. If you buy ’em right, feed ’em right, and sell ’em right, you might not lose too much money.”

At his busiest, Joe runs two herds, rotating them among five pastures to prevent overgrazing. All he feeds them is grass, ten or so acres per beast, plus some protein supplement cubes. “Grass is so basic,” Joe said. “It’s your feed. And it’s cheap.” He knows Texas grasses down to their roots. As we barreled across his property in a carryall—not letting the absence of a road stop us—he identified three-awn, with its tribristled ends; four varieties of the hardy, upright bluestems, the most common grasses in Texas; another grass dynasty, the gramas (including sideoats grama, our state grass); and lesser types, like switchgrass, wild rye, and the uncommon sand bluestem.

Sand bluestem isn’t common because it is what ranchers call a decreaser—under prolonged grazing it disappears. The only clump of it we saw was in an old, unused roadbed fenced off from the herd. Joe Franklin’s constant dilemma is to prevent good grasses from being grazed out while keeping poor grasses from taking over. An increaser, such as three-awn, is a so-so species that responds favorably to grazing and spreads rapidly at the expense of more desirable grasses. Joe maintains “rest areas,” such as an empty branding pen, to watch what nature does unhindered. Inside the pen the grasses were shoulder-high and lush compared with the munched-down rangeland.

Joe loves other flora too. He knows the flowers, weeds, bushes, and trees on his land. West Cantonment Creek, which crosses his land, is given away by the curtain of cottonwoods, locusts, mulberry, and elm along its banks. He pointed out an imposing black walnut tree (“the old patriarch”); a honey locust (“I don’t believe you could climb it if a bear was chasin’ you”); and a button willow, decorated with little yellow bobbles like bedspread fringe (“I never found anything good to say about a button willow”). The wealth of trees helps make the Franklin ranch truly pretty—not the usual adjective applied to Panhandle scenery.

The ranch house overlooks the creek. It is a good-sized home that the family calls Early Serum Company, after the successful blackleg vaccine. The house is one of many buildings scattered like soapweed on the ranch: stables for twenty cutting horses, the original farmhouse (circa 1900), a toolshed, kennels, a trailer house for the seasonal help. There is a large barn for hay storage and the cavernous shop, where Joe knocks together his inventions. “Most of ’em end up in the junk pile,” he insists, but one success is a cattle cube feeder, a contraption mounted on a pickup that automatically dumps a certain amount of protein-and-salt cubes as the tires turn. Others are a windmill with a cable instead of a stiff rod, a quail feeder, an old brush chopper (“one of my unfinished symphonies”), and an oil-drum chariot for breaking horses to harness. Joe also says he built the first barbed-wire roller thirty years ago. The barbed wire, looped around a jeep wheel, is unwound as the vehicle moves. It was a lifesaver in a land where wire-stringing is an eternal chore.

Having lived on a ranch for so long, Joe has amassed a wealth of facts and tidbits. As we bucketed along, he told me that cow chips are the hardest things to extinguish in a prairie fire and that you can fish a tarantula out of his hole with a wad of chewed bubble gum on the end of a string. He identified wild plums, which are great for jam, and snow-on-the- mountain, which is a favored quail chow. He knew green Russian thistles (posthumously called tumbleweeds) and aromatic sumac (also called skunkbrush). Joe had done his homework on his foe and co-worker, nature.

He waved an arm at the sweep of land before us. “A hundred years ago I would have been an Indian and ridden around looking at grass and buffalo,” he said. “I’m not too impressed with what man’s done.”

Luck of the Drill

When I was a kid, I used to wonder why the Panhandle wasn’t covered with those Eiffel Tower–looking derricks that appear on state-map place mats in coffee shops. They looked so dramatic, but all we had were pumping units, black and a little rusty, salaaming creakily like old, obsequious crickets. Oil and gas is just a dirty, smelly industry, to anyone without royalties, but it had its dramatic side once, and a lot of Panhandle folks remember that time. One of those people is Lawrence Hagy, 88 years old—“born in the last century”—a veteran of the Borger oil boom. The industry took him a long way. In his office in Amarillo’s First National Bank, where he still checks in every day, is a map of Gray and Carson counties showing his leases in pink; the overall effect is practically roseate. Behind his desk hangs a painting of his first well, and nearby is his official 1948 mayoral portrait.

Hagy, as everyone calls him, is a big, cheerful man with manners and attire too polished for a roughneck, but that’s how he started out. He moved steadily up, advancing to tool pusher before he decided it wouldn’t hurt to have a geology degree from the University of Oklahoma. “At that time geologists were something new. Now they’re just about one jump ahead of a doodlebug expert,” said Hagy. “But companies were hiring geologists then because they were learning that oil accumulated in structures. When I graduated, I went and asked my dad which company he thought was the best. He said, ‘Lawrence, if you can make money for them, you can make money for yourself.’ So he furnished me a little money, and I had a little money, and I came out to the Panhandle, because I’d read about all the gas out here but no oil to be found, and bought some leases, which are now in the Borger oil field out here.”

The discovery changed the Panhandle. In that one year, 1926, the Borger oil field produced 26 million barrels of oil; the year before, it had produced a mere million. In three months 30,000 people poured into the Panhandle, creating Borger in the process. There was money in the air, and everyone wanted a piece of it.

Hagy once had to pay hugely inflated fines to the sheriff and judge to bail out his entire derrick crew, who had been arrested for carousing. And though he was lucky enough to own a house, Hagy liked the tent city of Borger with its “debutantes,” drunkards, and con men. “It was just a-blowing and a-going and just as wide awake at three in the morning as it was at ten o’clock at night,” he recalled.

Hagy acquired two partners, Don Harrington and Stanley Marsh, Jr. “Harrington was a good landman and handled the office work. Marsh could get along with the farmers and ranchers well and was out in the country buying leases. Frankly, I don’t think I ever did very much. I just had a lot of friends.” The partnership flourished; in one case the three men acquired 10,000 acres for $1 an acre, then resold the land to Humble Oil for sixteen times as much.

At first Hagy could make money from oil but not gas. “It was just like gold on a desert island,” he said. “If you couldn’t sell it, it wasn’t worth anything. We had the gas out here, and they needed it in Kansas City and Indianapolis and Chicago. But the companies that owned the big pipelines wanted to take their own gas and not give us a market. They didn’t want to pay us.”

In 1933 Hagy went before the Legislature to argue the case for proration, which would ensure that even smaller operators in an oil field were compensated for their share of the field’s gas production. Proration is gospel today, but back then it was heresy, and Hagy’s attempt failed. So he returned to the Panhandle and took on the pipelines in the field. “We built a gasoline plant over there, and just took the gasoline out of the gas, and blew the residue to the air, which was very wasteful,” he said. “After that went on for a year, the companies decided it was better for them to preserve the reservoir and to take gas from everyone.” As a result, Hagy and his partners got a nice contract for their gas, and like most in the fuel-rich Panhandle, they easily survived the Great Depression, which devastated the rest of the dust bowl.

Hagy not only survived; in 1940 he bought an interest in the First National Bank. During World War II he was commissioned by the Air Force to advise the Soviet Union on rebuilding its bombed gas lines. He ran for mayor of Amarillo and was elected handily: “They didn’t know me very well, I guess.” During his term Hagy, always ahead of his time, pushed for the Canadian River dam and reservoir that supplanted the Ogallala Aquifer as Amarillo’s domestic water source.

Like all oilmen, Hagy loves land, and he owns the 38,000-acre Bitter Creek Ranch, a “horse pasture” that once belonged to the legendary cowman Charles Goodnight. Hagy runs a few head of Hereford, but, he said he can’t make any money ranching. “Now, you can be a success in the oil business and be rich,” he said. “I like my business. I was just lucky. I’ve always been lucky. And it happened right in front of me.”

Future Steaks

I can remember explaining to a Northern visitor what feedlots were and hearing her exclaim, to my bafflement, “Oh, poor cows!” I didn’t regard cows as poor or anything else. Cows meant two things to me: beef and stink. The latter comes from the Panhandle’s many feedlots, where cattle are fattened up to do their duty. You can smell a feedlot miles away.

Midway between Pampa and Wheeler, on the site of a World War II air base, is Moody Farms, its pens built atop a mile-long runway. It is a relatively small operation, fattening 20,000 head of cattle a year. Its manager, Rex McAnelly, who has a wide grin and a girth to match, told me that most of the cattle are crossbred and come from East Texas and as far away as Florida. The feedlot contracts to fatten them for their owners. When shipped in, heifers weigh about 550 pounds and are priced at 70 cents a pound; steers, about 100 pounds more at 75 cents. That’s $14 million worth of beef on the hoof, which requires some $3 million worth of feed and drugs annually.

Moody Farms grows, mixes, and produces its own feed. Steve Alexander, who described himself as “twenty-eight and wore out,” ran the mill the day I visited. Lanky and laconic, wearing a gimme cap with “Beef” stamped on the silhouette of a cow, Steve had worked in feedlots for ten years. His bailiwick is a corrugated-steel palace with kernels crunching underfoot and the moist, sweet odor of hot grain hanging in the air. Outside, two tall granaries store half a million pounds of raw milo, which is four days’ supply.

Inside the steam room, the milo is cooked and rolled. At the control area, a single worker sits in front of a panel that looks like the dashboard of a Buck Rogers vehicle. He inserts a computer card, and the correct dosage of antibiotics and fly-control drugs is added to a gigantic mixture of cooked grain, protein supplement, alfalfa, molasses, and fat. The final mixture is poured through a giant funnel into waiting trucks that dispense the feed into troughs, or feed banks. The mill mixes 35 batches a day of the bovine porridge, seven days a week. The mixture is so rich that new cattle get drunk on it; to prevent this the cattle are first fed hay, then introduced to the grain little by little.

The big challenge in a feedlot is to keep from running out of food. Moody Farms employs several hands to check the feed levels, because if the feed runs out, the cattle will overeat when it reappears and get drunk all over again. During my visit, a recent rain had rendered supper inedible, and the hands were busy shoveling it out. The feed banks border the pens, each of which holds a few hundred head and receives five tons of grain a day. Manure is everywhere; workers periodically clean up with a front-end loader.

Steve and I made the rounds in his pickup, and he pointed out the difference between residents of various pens. The old-timers were fat and stolid, mouths rotating without pause; the others, newcomers, were thin, listless, and “poor as snakes,” Steve said. “When you get ’em like that, you can’t hardly keep ’em alive.” We drove past the vaccination shed, formerly the hangar, and the hospital shed, where each patient is doctored up more than an only child. “So far this month we’ve only lost fifteen head,” Steve said. “I lost ninety-nine my first month. These green southeastern cattle come in sick from a warm climate to this freezing place up here.” Outside was a dead cow. “Need to do an autopsy on him,” Steve said. The cause of death could be polio, encephalitis, pneumonia, or respiratory trouble. The carcasses attract coyotes, which skulk around the feedlot at night.

When we drove back to the office to rejoin Rex, I realized I hadn’t smelled anything in an hour; my olfactory system had shut down in self-defense. As we passed, the cattle looked up with colossal disinterest before returning to their supercharged feed. I might have felt sorry for them if beef didn’t taste so good.

Voices From the Past

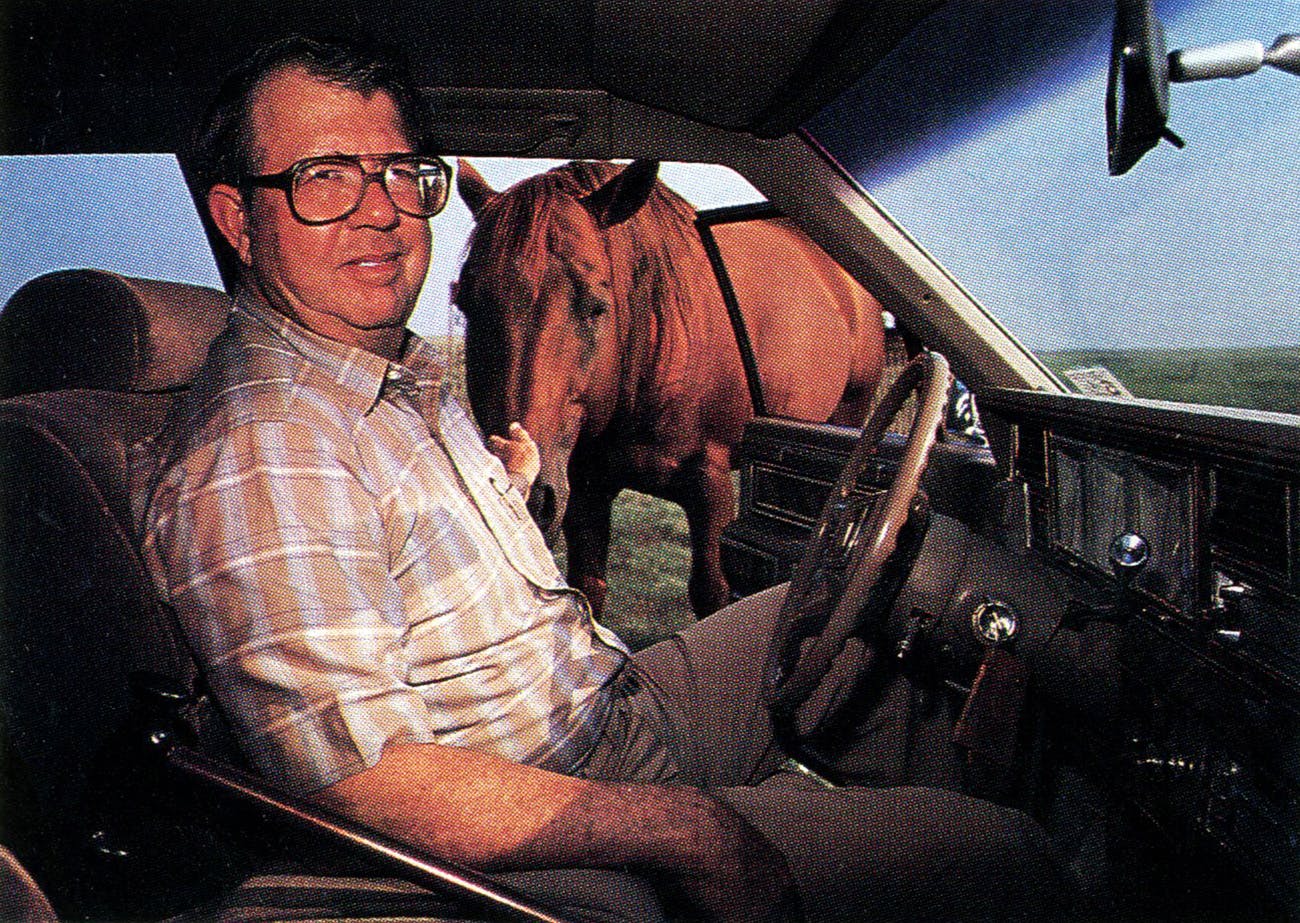

Rex McAnelly, like many Panhandlers, diversifies. To survive, if not succeed, you have to, because most area industries are at the mercy of nature. Rex owns a thousand head of cattle at the feedlot, but he’s a farmer too; he owns some 2,500 acres of land, a good bit of it planted with wheat.

Most of Rex’s land is leased to Moody Farms for raising feed grain. Driving around in his three-quarter-ton pickup, he stopped to adjust the electric sprinkler system on a wheat field and to shut off a well, and he detoured by his picnic grounds near Sweetwater Creek. There are two barbecue grills, one unused since a pack rat moved in; Rex doesn’t have the heart to evict him. On a bois d’arc log was a giant web; its resident spider raised a foreleg in greeting.

We drove on, and Rex showed me his grandson’s land. “Your grandson?” I asked. “How old is he?” Rex was too young to have a farming grandson.

“Thirteen,” Rex said, “and I’ll be glad when he’s old enough to sign the notes.” He waved a hand at a sweep of the tortilla-flat ground. “That’s the kind of land that just holds the world together.”

Rex has in full measure the common Panhandle regard for the land as well as its history. He showed me a one-room schoolhouse and a “whiskey strip,” an unclaimed piece of land said to be created by a surveyor’s drunken error. He ran me by the Old Mobeetie jail, the first in the territory, and Old Mobeetie itself, at one time the self-styled Mother City of the Panhandle. On a half-section of Rex’s own land, the deed to which is signed by Theodore Roosevelt, lie the ruins of old Fort Elliott, built in 1875 to protect the buffalo hunters from the Indians.

Today the fort is no more than a heap of broken bricks and some stone steps leading nowhere, but it’s the only reminder of the greatest boon in Panhandle settlement before irrigation. A flat field of buffalo grass was the parade ground; an area pockmarked with rusty bits of metal, the smithy. Rex gave me a brick from the barracks and a muleshoe, longer and skinnier than a horse’s. “Here you go,” he said. “A paperweight and a good luck charm.”

He had one more thing to show me, and we barreled on down the rutty roads to a tilled field ready to be planted with winter wheat. He headed straight across it, following the tire marks left by an earlier visitor. “Life’s a lot easier in someone else’s tracks,” he said. He stopped in the middle, where on a rise stood a white lamb-topped tombstone: “Hattie, daughter of Wm. H. and M. L. Crisp, July 31, 1887. Aged 7 mos. 18 ds. At rest.”

“We’ll never know if she was the daughter of someone coming through or someone from the fort,” Rex said. But it didn’t matter. He fenced in the tiny grave, and today all around it grow reminders of a hard-won Panhandle civilization.

Political Asylum

One of the persistent Panhandle myths is its bleakness, its dry, dusty wastes. Those exist, of course, and they are the most familiar; wouldn’t you build the highway through the flat part? But there are plenty of oases. The Panhandle is dotted with little wooded patches where the traveler can take shelter from the overwhelming emptiness. Creeks were the best places for plants and animals, and everybody has his favorite.

I had come to Chicken Creek to talk to a genuine hermit, a Panhandle native who so thrived on the Panhandle’s combination of shelter and wilderness that he retired here 26 years ago, preferring the companionship of Chicken Creek to that of society’s. The creek is the site of a famous Indian massacre and not far from prime pronghorn grazing grounds. Under a warm winter sun the creek babbled, the insects droned, and two mule deer leapt out from the waterside shrubbery and fled, spooked by the sound of my car.

Mickey Ledrick comes from pioneer stock and was a pioneer himself in Texas’ Republican party. In 1950 he volunteered as campaign manager for Ben Guill, a Pampa man who ran for Congress as a Republican. Mickey had absolutely no experience; he recalled that he would “go from town to town and collar people on the street,” pleading for votes. It worked; Guill won, becoming the second Republican congressman from Texas at the time.

From there Mickey quickly moved up the political ladder: he staged Dwight Eisenhower’s 1952 campaign in Texas, moved to Washington to become an assistant postmaster general, and in 1955 became both an assistant to the chairman of the Republican national committee and the executive director of the Texas Republican party. But in 1961, after helping John Tower succeed to Lyndon Johnson’s U.S. Senate seat, he abruptly left politics, moving to a section of family land on Chicken Creek 25 miles from Pampa. “I wanted to get away from people” is all he offers by way of explanation. He has lived here ever since, most of the time without a phone. He likes the solitary life.

But he isn’t really alone. Deer, squirrels, turkeys, and raccoons know him and eat out of his hands. He provides grain, nuts, and seeds for them, getting up before they do to set out breakfast. He spends as much as $250 a month on groceries for his creatures, more than he spends on himself. As we talked, a squirrel gestured, annoyed, at the empty feeding cans while a turkey hen disgraced herself by losing her grip on the railing.

The deer are Mickey’s favorites. About twenty congregate on his front lawn for breakfast, and in cold weather as many as ninety appear in the food line. They regard him as their protector, pawing at the door to have him remove cactus spines or porcupine quills. His favorite doe, Mama, lets him know when a predator is too close for comfort. One time he heard her warning snort and stepped quickly to the door. “Here came that bobcat,” he said. “He had his ears laid back and his tail between his legs. Then I thought, ‘Wait, bobcats don’t have tails.’ It was a mountain lion. That lion tore the stomach out of one of my babies.” The mountain lion returned to lurk about his place for seven to eight years, once with two cubs, and “no one believed me but the game warden.”

During hunting season Mickey keeps a predawn vigil by the highway to watch for poachers. “Once, at five-fifteen a.m., I found a pickup parked inside my cattle guard. I got out my thirty-thirty. The hunter said, ‘You seen any yet?’ I said, ‘No, you’re the first.’ ” Mickey himself has never killed anything except a rabid badger and a skunk family of five who moved in uninvited under the house. “There’s a skunk graveyard over there a ways, and my conscience still hurts me.”

He has had plenty of opportunities to leave his place, among them offers to work for Goldwater, Nixon, and Reagan. But he is content with his life, his land, and his animals, although his former cronies don’t understand. “The state vice chairman and her husband showed up one day. I made ’em some coffee, and then I went out and called up my deer. I said to ’em, ‘Now, before you start on this pitch, do you think I’d leave all this, and go back into the wild life of politics?’ ”

For his visitors, the question was unfair, but if the Panhandle is in your blood, the answer is all too clear.

- More About:

- Panhandle