This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

An old fight over water is coming to a boil in Central Texas, a fight with all the conflict and character of an old western movie. There are farmers up in arms and big-city charmers, empire builders and nervous politicians. The very life of the prettiest river in Texas is in jeopardy, and numerous endangered species are at risk. So, some say, is progress.

The fight has been brewing for more than three decades, since 1956, the bottom year of the worst drought in Texas history. That was when the people who lived above the Edwards Aquifer realized with alarm that their blessings were limited, that their cool, clean, free water was not only not boundless but, worse yet, actually shared with other people hundreds of miles away—people who used the water differently, who were just plain different from them.

The focus of those watery anxieties—indeed, the source—is the aquifer itself, the miraculous limestone sponge that nature placed beneath the Texas Hill Country. Because the aquifer is hidden, it was taken for granted by the people who blithely relied upon it to sustain their lives. There were half a million such people in 1956. There are three times that number today, and they are rapidly draining the water celebrated in beer commercials and tourist brochures. The people who depend on the aquifer have been forced to consider doing voluntarily what Texans heretofore have done only at gunpoint: surrender their right to take all the water the law allows.

Next spring the Texas Legislature will decide whether to give the Edwards Underground Water District the authority to impose controls on pumping from the aquifer. The district, which was formed by the Legislature in 1959 in a foredoomed effort to contain the squabbling, was brought into existence with no power to protect the aquifer. Although the underground waters extend as far west as Kinney County (Bracketville) and as far north as Travis County (Austin), the district is made up of just five counties. On the west are Uvalde and Medina counties, both sparsely settled by farm-and-ranch folk who consider water inseparable from land and separately worthless. The opposite wing of the district, to the northeast, includes Comal and Hays counties, both of which owe their existence—past and future—to bountiful natural springs. The fifth county, the geographic and political pivot of the district—also the crux of the district’s problem—is Bexar County, occupied almost entirely by San Antonio. The ninth most-populous metropolis in the United States, San Antonio is growing faster than all but one of the first eight. It already is home to more than a million people, all of them squeezing the same buried sponge as the scattered farmers of Uvalde County.

“They’re out to steal my water, plain and simple,” fumes Maurice Rimkus. On the rear bumper of his pickup is a sticker that reads, “You Can Have My Water, Just Like You Can Have My Gun—When You Pry It Out of My Cold Dead Hands.”

As only a farmer can, Rimkus appreciates the value of water. His great-grandfather was unable to drill a dependable well and lost the farm, first to the mortgage company and then to his son-in-law and neighbor, Fritz Rimkus, who bought it from the lender three years later. A taciturn German who had been trained as a landscape architect, Fritz Rimkus walked around his new property until he found a big cut-ant mound, then drilled through the mound to hit the pool that he figured must be there. That was in 1903.

The well is still there, and it still flows with cool, clean Edwards Aquifer water. It is the difference between a working farm and a bad loan.

For 66 years the Rimkus farm, like most South Texas farms, was a dryland operation, which is to say it relied on rainfall to water whatever crops were there. Well water was reserved for people, livestock, and maybe a vegetable garden. In all of Uvalde County before the big drought, there were fewer than twenty real water pumps—big engine-driven pumps—and none of those belonged to farmers.

In 1969 Maurice Rimkus borrowed $75,000 from a bank to irrigate his farm, one of the first in the county to do so. The profit margin was lower than that in dryland farming because the overhead was so much higher, but there was more security.

“This is a semitropical climate around here,” explains Rimkus. “You get dry spells for a couple years, then you get wet spells. Nothing is consistent. With irrigation you don’t make as much money in a good year, but your cash flow is steady. And you don’t lose the place if you have a couple bad years.”

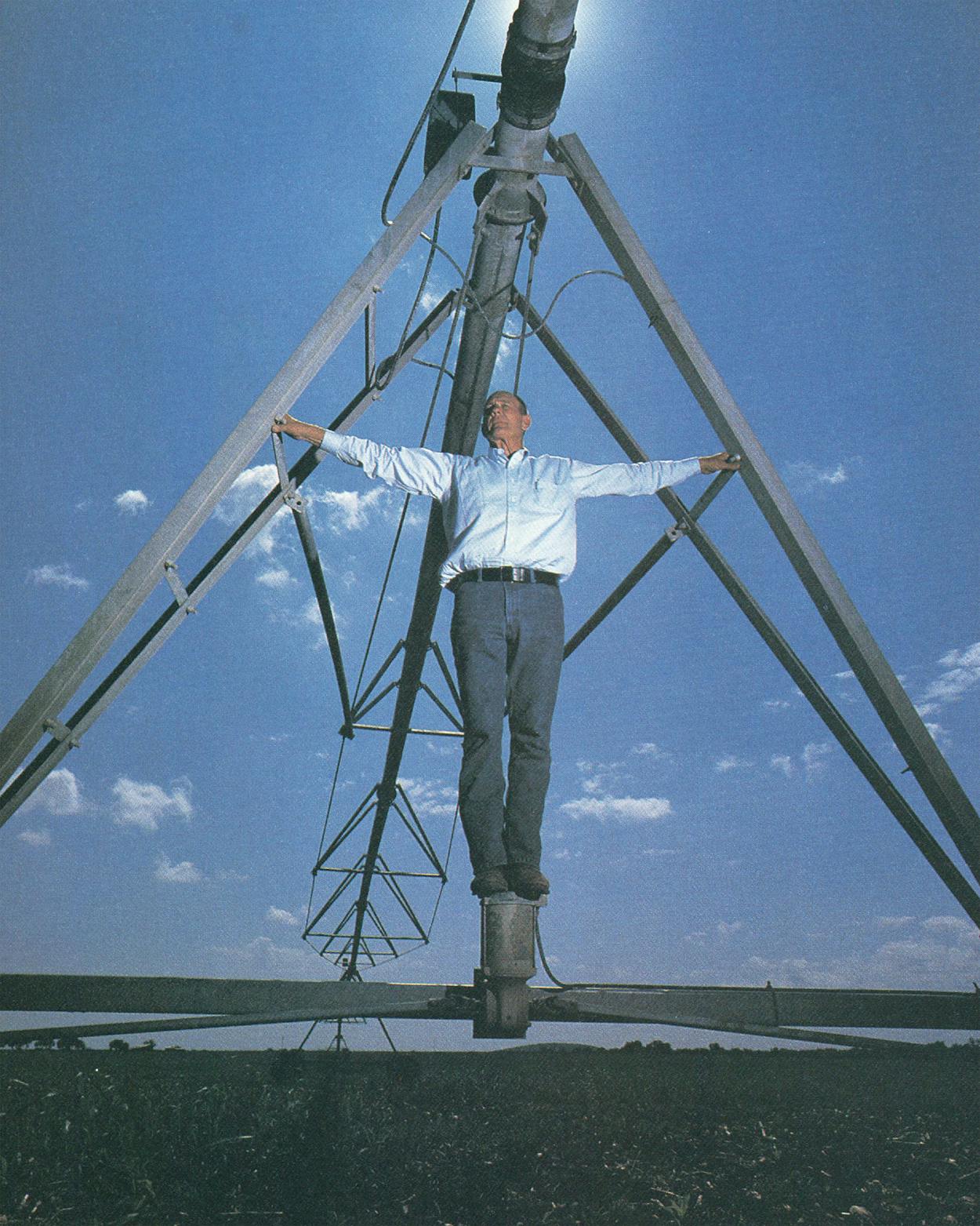

The logic was obvious not only to farmers but also to the bankers who cheerfully loaned the money to irrigate the land, which in turn rose in value. By 1988 Uvalde County had 319 irrigation wells, transforming the countryside from mostly dryland farms and ranchland into irrigated farms worth four times as much per acre, most of it mortgaged to the bank. Rimkus is still paying off the loan for the first of his six irrigation wells.

Rimkus has driven his pumps with diesel engines, gas engines, electric motors—all in an effort to minimize the cost of pumping water. He knows to the nickel what it costs to water an acre of cotton or corn, depending on the weather. A 20-mile-per-hour wind in a 100-degree ambient temperature, for example, evaporates 20 percent of his water before it hits the ground, so he doesn’t irrigate on windy days.

“You really have to live in harmony with Mother Nature,” he says. “That goes double with this aquifer too. Mother Nature runs the aquifer, not man. We can’t make it do anything that Mother Nature doesn’t want it to do.”

In the spring of 1986 Rimkus was appointed to the task force that developed the regional water plan that the Legislature will be asked to embrace next year. He spent more than two years attending meetings, studying the issues, and being an involved citizen. He has admiring words for his counterparts, but he wants no part of the regional water plan.

“It’s not our problem,” he says. “We don’t have no river walks and water worlds. We don’t have big, stupid fountains spraying water all over everywhere. You go down to that HemisFair there, they got those silly fountains doing nothing but evaporating! We didn’t cause the problem, we can’t fix the problem, and we don’t want any part of the problem.”

The Edwards Aquifer is a subterranean analogue of the Texas Hill Country. The gentle ripples and sudden little valleys of the land’s surface are reflected underground in the veins and hollows formed by the same slow process of water dissolving limestone. The surface waters—rains and rivers, creeks and washes—have patiently shaped the undulations that give the Hill Country its topography. The underground waters, unseen but just as patient, have created the Edwards Aquifer.

Everything we know about the aquifer is by inference or accident or studious, dumbstruck observation. Creatures that live nowhere else on earth live in those dark, hidden waters—catfish that have no eyes and whose brains show no vestige at all of an optic nerve. The catfish have survived and evolved in lightless secrecy for eons. When their ancestors last saw the sun, man was still in awe of fire.

An entire biology that has no need for sunlight flourishes in the waters of the Edwards Aquifer. Representatives of more than forty species—flatworms and snails, salamanders, shrimps and fishes, all sightless and colorless—have been flushed to the surface in some haphazard and, for them, disastrous way. There is no telling what others might live contentedly down there. The biggest blind catfish we know of is just five inches long, the diameter of the average well pipe, which is what sucked the creatures out of their watery blackness and into our world.

The Edwards Aquifer holds trillions of gallons of water, every drop of which fell from the sky in the last few thousand years. Most of the water began as rainfall on the Edwards Plateau, the broad limestone tableland that slopes toward South Texas, gathering runoff into streams and rivers that drop off the Balcones Escarpment and flow freely for a while through gentle hills, then vanish abruptly. The Frio River, for example, loses more than 600 million gallons, or 80 percent of itself, daily within a fifteen-mile stretch, shriveling from a genuine river to a pitiful creek.

All of that missing water falls through cracks in the earth: innumerable, imperceptible fractures and fissures that collectively amount to one giant gash 20 miles wide and 175 miles long, running west to east under a dozen rivers that flow mostly north to south. It is a 30-million-year-old flaw in the earth, the Balcones Fault. That enormous collection of tiny openings is the aquifer’s recharge zone, and into it during an average year pour 200 billion gallons of clear, fresh Texas Hill Country water that otherwise would keep flowing southward.

Instead the water moves eastward through the pores and channels of the aquifer, trapped between a bedrock floor and a ceiling of impermeable Del Rio clay. In places where that ceiling has collapsed, we surface dwellers find exposed caverns or natural springs. Those springs and caverns, the largest in Texas, are also among the largest in the world.

Exactly how fast and how steady the water moves eastward is a meaningful question to the people living above the aquifer. But there are people who would like us to believe that the water doesn’t really flow in any significant way, that it merely sinks to its lowest possible level, percolating downward. And undoubtedly there are such traps and sinks: deep, black, quiet pools that hold ancient rainwater in their bottoms, going nowhere. Those lucky enough to have wells that have hit such pools have the richest water wells on the planet.

But the U.S. Geological Survey, in sophisticated experiments using dye tracers, has proved conclusively that the waters do flow, at least through portions of the aquifer and across known distances. The waters flow between San Antonio and San Marcos, imperceptibly or not, at an average rate of one mile per year. For underground water, that is considered a regular torrent.

That flow has vital meaning on the surface because it puts San Antonio and the people who live there downstream from Uvalde, and it puts San Marcos and the people who live there downstream from San Antonio. And like all people who have ever lived downstream from anyone else, those people have concern for the water that reaches them and anxiety about the water that someday might not reach them.

For five months in 1956, during the nadir of the terrible drought, Comal Springs near New Braunfels went dry. Crystal-clear water no longer came burbling up from the parched earth like some sort of miracle, which is what the people who lived in the area had grown accustomed to over the years.

“It was a tremendous shock,” recalls John Specht, who as a boy went swimming on hot days in Comal Springs. In 1956 he was a senior majoring in range and forest management at Texas A&M. “I came home every weekend I could. I remember burning cactus so we’d have something to feed the cattle.”

That summer the Comal River, which begins at Comal Springs, shrank to a muddy dribble. The San Marcos River, which relies on San Marcos Springs, twenty miles northeast of Comal Springs, lost two thirds of its normal flow. Those are the two largest springs in Texas, and those two rivers, the Comal and the San Marcos, are the principal sources of the Guadalupe River. The Guadalupe flows across four hundred miles of Texas’ best farmland, from the Edwards Plateau to the coastal plains, where it issues San Antonio Bay from its mouth.

From beginning to end the Guadalupe is a lovely river. Summer camps line its upper reaches. Below Canyon Dam, it is a weekend retreat all summer long for thousands of urban Texans who rent inner tubes to float along it for a few miles just to restore their spirits.

“I don’t think there’s any question that the Guadalupe is the major recreational river in the state,” says Specht, who himself has canoed it below Canyon Dam. “We have an obligation to protect it.” That is Specht’s job these days. He is the general manager of the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority, created by law to develop, conserve, and protect the water resources of the Guadalupe River Basin.

Of necessity, the conserving and protecting aspects have focused on the river’s vulnerable headwaters, while the development aspect has centered on the two hundred miles between Seguin—where the authority is headquartered—and San Antonio Bay. In addition to the towns (Kerrville, New Braunfels, Seguin, Luling, Gonzales, and Port Lavaca) and farms that have always depended on the Guadalupe’s water, now there are major industries that are equally dependent: the petrochemical plants of Calhoun County, Central Power and Light, and big rice plantations along the coast. All of those entities have water-use permits issued by the Texas Water Commission. They each withdraw water from the Guadalupe and return used water to the river, according to contracts and requirements imposed by the State of Texas, which owns the water in public trust.

Holding this all together has been Specht’s concern for the past twenty years—he joined the river authority in 1965—and expanding that role for the next twenty years is his ambition. He has dreams of dams and enormous reservoirs, of prosperity and progress through the wise manipulation of Mother Nature.

“We’ve hardly begun to really develop the Guadalupe,” he says. Specht is a large, quietly amiable man who wears plain brown boots, an Aggie class ring, and the earnest manner that seems always to go with them. It’s no surprise that he worries a lot about the Comal and San Marcos springs. If they ever go dry again, he’s up the creek. “If we lose the springs,” he says, “we lose the river.”

And the biggest threat to those springs is the city of San Antonio, sprawled atop the Edwards Aquifer, sucking up water that would otherwise quite naturally come burbling out of the earth at New Braunfels and San Marcos. “They have wells in place right now and enough pumping capacity that they could take it all,” says Specht of the city of San Antonio.

In 1957, after the drought, the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority sought permits to store water at a proposed dam on the Guadalupe in Comal County for use in dry seasons. The City of San Antonio contested the permits and sought to have access to the water but lost its case in the Texas Supreme Court. So Canyon Dam was built. Eight years later the result was Canyon Lake, full of cool, fresh Hill Country water and the only significant reservoir in the Guadalupe River Basin.

In the mid-seventies the City of San Antonio approached Specht about buying water from the lake. Specht was only too happy to oblige, since it would help relieve the city’s worrisome draw on the Edwards Aquifer. A contract was negotiated and presented for approval to the San Antonio City Council.

The politicians killed the deal by a vote of 6–5. The swing vote against it was cast by a young councilman named Henry Cisneros, who could see no reason to buy expensive lake water when cheap, practically free, clean water was available right underneath San Antonio.

“I just don’t believe it’s necessary,” said Cisneros at the time.

John Specht was fit to be tied.

The urban geography of Texas is basically an overlay on a map of Texas’ waterways. Fort Worth is where it is because the Trinity River’s North Fork and Clear Fork come together at a cattle-fordable crossing there. Dallas is where it is because the three main stems of the Trinity conjoin there. Houston is where it is because Buffalo Bayou eventually became what the founding hustlers claimed it to be, a navigable passage.

And because weary and thirsty Spanish explorers found two fabulous natural springs at the present site of San Antonio, they took it as a sign from God to quit wandering around and settle down. For the next three centuries the San Pedro and San Antonio springs provided all the water that the settlement, then the town, and finally the city needed. The water came out of the ground all by itself, always cool, always clear, easy as you please.

Not until the 1890’s did citizens find it necessary to drill water wells in San Antonio. They didn’t have to drill very deep, less than a hundred feet in most places, and they didn’t need to pump the water out. It seemed so simple that nobody worried when San Antonio Springs went dry in the 1920’s.

San Antonio has always thought of itself as a water-rich city. Indeed, water was its only favorable natural resource. Other Texas cities had nearby timber, oil, or navigable rivers to drive their early economies. San Antonio had nothing but easy drinking water.

That was enough to enable San Antonio to become the great modern city it is. Easy water was a form of municipal subsidy. Other cities in Texas have had to invest in expensive surface-water systems of dams, reservoirs, treatment plants, and overland pipelines to supply their needs. A city the size of San Antonio, even if it were situated smack alongside a major river—like Dallas is—normally would still require at least two gigantic filtering plants to make its water drinkable.

San Antonio’s water has always been treated by the aquifer. The water comes out of that limestone sponge already more pure than the requirements of the strictest quality standards. There are $150 million treatment plants that can’t filter water as well as the aquifer does.

San Antonio just chlorinates its water a bit in case some contamination occurs in the pipes, then the water is pumped straight out to homes, offices, public fountains, car washes, and golf courses. The River Walk is maintained this way, not by any river but by city-owned pumping stations. More than fifty such stations in Bexar County provide San Antonio with its water supply.

At least three hundred other pumps are operated by private companies and individuals in Bexar County, all sucking water from the Edwards Aquifer. They have no permits, no regulations, no restrictions at all. That is the big difference between surface water and underground water: Anyone who feels like drilling a well can do so.

Bexar County pumps more than 100 billion gallons of underground water a year, 60 percent of the annual total pumped from the aquifer. Both the amount and the percentage are projected to increase as the city grows.

“It obviously can’t continue,” says Tom Fox, for almost ten years the general manager of the Edwards Underground Water District until he left to enter private business in October. “The notion that nothing will happen is just not an option anymore. If we hope to save this aquifer for our grandchildren, now is our last chance to do something.”

The district has no authority to regulate water use anywhere in its five-county territory. The bill that created the district in 1959 allows it only to plan and monitor. There have been several attempts to revise that bill to give the district more authority, but they have always failed.

Fox has tried for the past decade to grow a backbone in his study committee and to put on some political muscle. “Those plans failed not because they weren’t good plans but because they lacked public support,” Fox says. “And they lacked public support because there was no public involvement in the process.”

Six years of public involvement produced in September 1983 only a memorandum between the City of San Antonio and the Edwards Underground Water District commissioning a formal study. It was the first agreement on anything between the city and the water district and the first acknowledgment by San Antonio that it might actually have water worries and need help resolving them. The detente was symbolized by the first visit ever by a San Antonio mayor to an Edwards Underground Water District board meeting—it was the same Henry Cisneros who had killed the Canyon Lake contract as a councilman.

San Antonio is a relatively poor city even by tight-belt, post-boom Texas standards. The city’s per capita budgets for police, fire protection, libraries, and parks and recreation are all well below those of Fort Worth, Dallas, Houston, or Austin. Spending money on big new water projects could only depress those figures further. That was why Cisneros had voted against buying water from Canyon Lake back in 1976; he didn’t see how the city could afford it.

But as the mayor, he couldn’t see how to avoid the problem any longer. Cisneros’ new attitude was apparent in the spring of 1984, when he persuaded the city council to start promoting conservation measures instead of just acting like a wholesale supplier. The impact was minimal, but it signaled a sea change in municipal thinking about water use.

The consultant’s Regional Water Resource Study required nearly two years of pondering at a cost of $600,000. It found that at current pumping levels, a major drought—even a shortlived drought—would ruin everyone who depends on the Edwards Aquifer: Farmers would go bankrupt, city dwellers would go thirsty, springs would go dry, the Guadalupe River would be lost. Even without a drought, growth would achieve the same results in thirty years. Something obviously had to be done. But no one was willing to relinquish their precious water rights, so another committee, the biggest one yet, was assembled. Called the Implementation Advisory Task Force, it was instructed to come up with a plan for action.

In 1987 the need for a regional drought management plan was begrudgingly accepted by all the factions of all five counties. Because the Legislature heard none of the violent objections that previous bills inspired, a new law was passed in a blur. The Edwards Underground Water District eventually adopted well restrictions and pumping limits—both unprecedented forms of regulation in Texas—but only in certified emergencies and with established trigger conditions. It was a blueprint for coping with disaster, nothing more.

Since such emergencies are inevitable if unabated pumping continues, the task force kept on working. It still had to come to grips with the essence of the problem: There is more demand for water than the aquifer can continue to supply. It is possible, perhaps, to satisfy the short-term needs of everyone in the region without regulation, conservation, or additional reservoirs. For instance the Comal and San Marcos springs could be replaced by enormous wells and mighty pumps, thereby manufacturing the Guadalupe River. It is also possible to slake the growing thirst of San Antonio by uncontrolled pumping for a decade or so—maybe. Nobody is sure how long the aquifer will last, but there are plenty of people in the district—farmers in Uvalde, among others—who are willing to risk it.

That would kill the Edwards Aquifer, of course. Even if it holds enough water to supply everybody’s needs for ten or twenty years—nobody honestly knows—it would die in the process. The water table would quickly drop below ages-old levels, leaving dry many channels leading to who-knows-where. Stagnation would set in. Bad-water zones already are known to exist in the aquifer, areas of water that go sour and brackish when cut off from the main stream. Such zones would proliferate unpredictably and contaminate ancient pools with modern poisons.

The aquifer’s underground denizens would be wiped out in short order. They are the most vulnerable of all the creatures who depend on the aquifer’s constant freshness to survive. Eventually the despoiled waters would come to the surface—pumped or not—to pollute the Guadalupe. And man, the least sensitive of the species dependent on the Edwards Aquifer, will surely feel the effects. Fortunes will be spent either to pump clean water or to treat bad water, and the line between the two will shift from year to year according to nature’s whim and man’s response.

Hearing all that occasioned a remarkable transformation among the members of the task force. In July of this year they released a regional water plan that none of them will brag about but all had a hand in. The fifty-year plan, which must have the blessing of the Texas Legislature, calls for a limitation on well drilling throughout the district, pumping limits based on past consumption, fees for new users, and potential fees for old users. For the first time in Texas history, the plan would separate groundwater rights from land ownership within the five counties of the district.

The plan also calls on the City of San Antonio to impose conservation measures and develop ways to reuse its wastewater. The city would also be required to finance four new reservoirs in the Nueces and Guadalupe river basins, together with the requisite filtering and delivery systems. The whole plan is expected to cost $1.7 billion over the next fifty years.

The regional water plan is a cornucopia of bad news for everybody in the district. It is a wonder the task force participants haven’t been hanged in effigy in front of all five county courthouses.

“It could have died very easily,” admits Carl Raba, Jr., a hydrologic engineer who served as the chairman of the task force steering committee. “Certainly there are aspects of the plan that people don’t like, and we didn’t expect them to like it.

“But in the end consumers will be paying about the same rates as people in Phoenix or Dallas. For years we were blessed with cheap water in this region, or at least we thought we were. Now we’re going to start paying a real price, a realistic price.”

Not surprisingly, a deep bellow of outrage reverberated throughout the district when the plan was announced, as if everyone’s plumbing had backed up at once. It was the kind of reaction that under normal circumstances would have sent every politician in the region into hiding.

That didn’t happen, though. The first political test of the issue—two tests actually, a week apart—came before the San Antonio City Council in mid-July. The first was whether to spend $180 million to dam the Medina River and create Applewhite Reservoir, the first of the four proposed reservoir projects. The second test, but largely predicated on the first, was whether to adopt the regional water plan.

In typical San Antonio fashion, there seemed to be as many factions in the city as there were pumping stations. Activist groups appeared out of nowhere almost overnight, replete with buttons, bumper stickers, and recall petitions. The most astounding coalitions were formed: clergymen and local brewers (Lone Star and Pearl beers are aquifer products), West Side activists with North Side developers. When the vote on the Applewhite Reservoir came up, the council chamber had to be cleared several times by fire marshals to keep the number of people under the 185-person limit. The session was chaotic and histrionic, and it took all day, but the final vote was 8–3 in favor of the reservoir. One week later the vote was 9–1 in favor of adopting the regional water plan.

But there was a dissonant chorus from the west. Within days came the news that Uvalde County was trying to secede from the Edwards Underground Water District.

In early September the district’s board of directors, which is composed of three members from each of the five counties, voted 9–6 to accept the regional water plan. All of the opposing votes came from the western agricultural counties, Uvalde and Medina. Grass-roots petition campaigns were begun in both counties to force a referendum onto the January ballot, allowing the two counties to withdraw from the district. In both counties proponents of succession expect no problem in acquiring the number of signatures needed by the November 1 deadline.

“I’ll bet you right now,” says Maurice Rimkus, “that we’ll have ten times more people vote in Uvalde County in January to withdraw from the district than have ever voted in a water district election. It’s the hottest issue we’ve ever had around here. We want to show the Legislature that we don’t want any part of this plan.”

That probably guarantees the Legislature will dodge the issue. The unrestrained capture of underground water has been sanctified as a God-given right in rural Texas, and horror stories from strange lands like California—where coastal cities have claimed the water under inland rural areas—only strengthen the resolve of Texas farmers.

The fear of subjugation, more than the prospect of regulation, is what upsets Rimkus. “This fight isn’t really about water,” he says. “It’s about power and politics and who’s gonna run your life.”

- More About:

- Water

- TM Classics

- San Antonio