On February 9, 1964, Paul McCartney counted off “All My Loving” on the Ed Sullivan Show and the whole free world freaked out. That night 73 million people watched the Beatles, four spectacularly young, handsome men dressed in black suits and pointy boots who shook their heads, sang chirpy choruses, and smiled sweetly at the screaming teenage girls in the audience. By the time they were done—the group played four songs, ending with their number one hit, “I Want to Hold Your Hand”—the country seemed like an entirely different place. Just eleven weeks before, President Kennedy had been assassinated. Now everything was as fresh and new as these four creatures from Liverpool. It was the first shot of the British Invasion. It was the beginning of the Sixties.

It was the end of David Lott’s flattop. The McAllen fourteen-year-old had been doing his homework in his room when his mother, watching the show, called to him, “You’ve got to see this!” He ran out, and like every other teenager in America, he was stunned. The guitars, the drums, the harmonies, the hair, the boots. The girls. “The next morning,” Lott remembers, “I put some butch wax on my hair and started combing it down.” He also bought a pair of drumsticks and started banging on tables and chairs until his parents finally got him a set of drums. That first night with his new toy he practiced for eight hours, until a neighbor called the police.

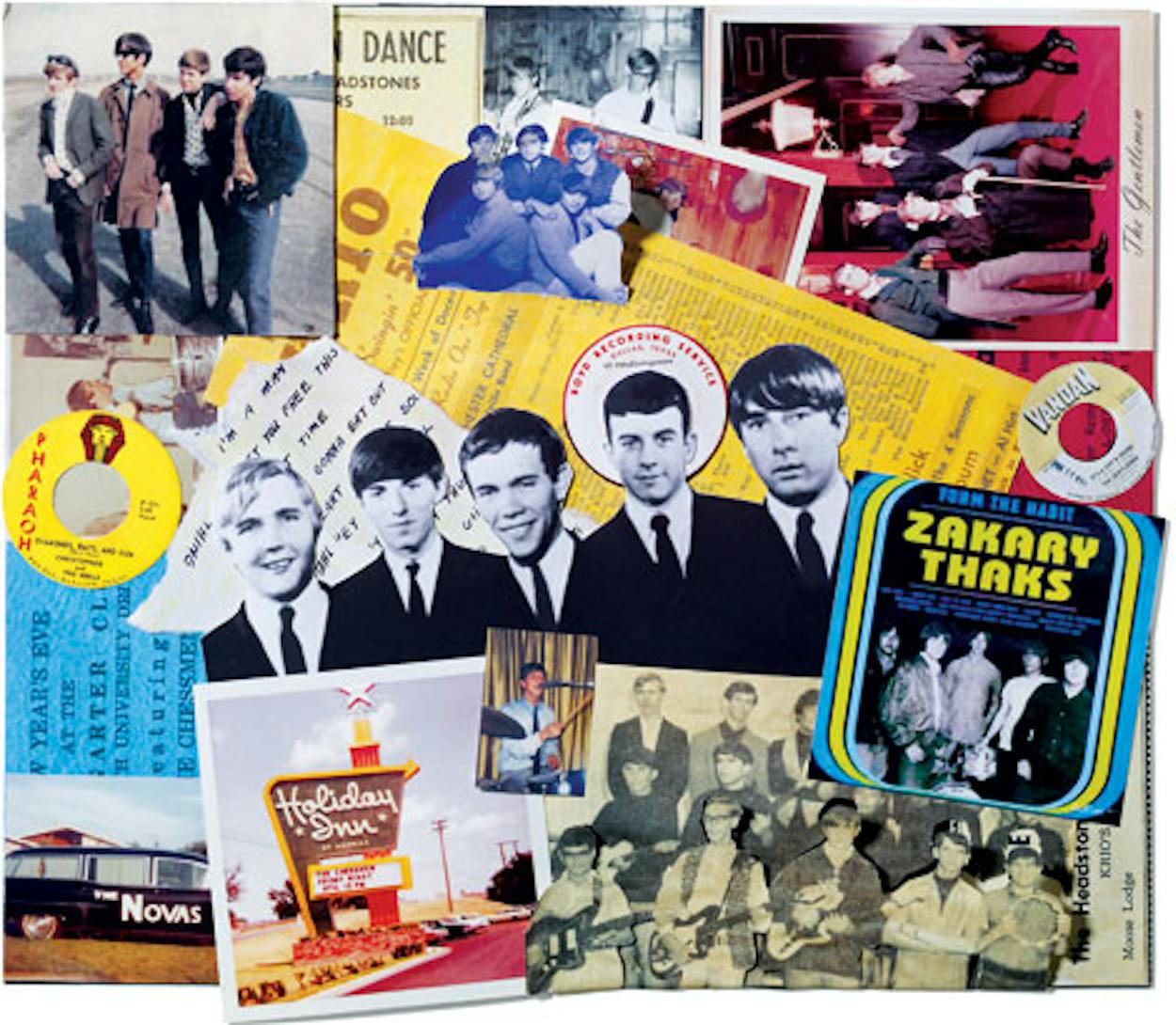

Lott began playing surf songs and instrumentals with a couple kids from down the block, Mitch Watkins and Jerry Ebensberger. By then other big-name groups had followed the Beatles—the Dave Clark Five; the Rolling Stones, who were on their first American tour; the Kinks, whose song “You Really Got Me” was a huge U.S. hit. And in McAllen and the surrounding area, bands were popping up everywhere: the Playboys of Edinburg (named after the nearby town, not the city in Scotland), the Headstones, the Invaders. A singer and guitarist named Javier Rios—who enticed a drummer and a bass player to don Beatles wigs and back him up on a medley of “Twist and Shout” and “La Bamba” at a McAllen junior high school talent show—started the Cavaliers. Then there were the Souls, begun by five eighth- and ninth-grade Beatlemaniacs, including guitarists David Smith and Jay Hausman. Smith was one of the first Beatles fans in the Valley—an English cousin had sent him a copy of “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” before it was released in the U.S. “I put it on my little turntable and it just jumped off,” he told me. “I thought, ‘Yeah, I want to do this.’ ”

The Souls played parties and dances but had to stop when the drummer graduated in May 1965 and the bass player left. Smith and Hausman knew Lott and Ebensberger and invited them to become the new rhythm section. By the end of 1965 this version of the Souls was taking turns practicing in one another’s dens. They were doing note-for-note imitations of songs like “Off the Hook,” by the Rolling Stones, and “Hitch Hike,” the Marvin Gaye song covered by the Stones. But they were reinventing themselves as they did it. They were getting cooler.

The Souls played teen dances for the Methodist Youth Fellowship and the Catholic Youth Organization and then moved up to gigs at places like the Moose Lodge and the Grapefruit Bowl. Their set was mostly covers of British Invasion tunes but also some American rock and roll songs, such as the Standells’ “Dirty Water.” They would borrow a family car and drive to Mission to play at the Community Center or to Harlingen to play the Hide-A-Way Club. Sometimes they performed for free, other times they earned as much as $200, good money for a bunch of teenagers. They’d finish by midnight and drive home.

In the summer of 1966 a friend of the band’s named Christopher Voss approached them with a couple teen-angst poems he thought would make good songs: “Broken Hearted Lady” and “Diamonds, Rats, and Gum.” Voss and Smith sat around and worked them up as songs—the first as a jangly ballad, the second as a rocker. Voss offered to pay for time in a studio if he could sing the songs and put his name in front of the band’s. The others agreed and went into Jimmy Nicholls’s Pharaoh Studio, on the south side of McAllen, to make a record. “It was a converted garage,” recalls Smith. “I remember Jimmy lifting up the big aluminum door.” The Souls recorded the songs live, with no overdubs, so they had to play and sing perfectly. It took multiple takes to nail the ballad, but “Diamonds, Rats, and Gum” was done right the first time. Even today, the nervous energy of the song—a weird, needy teen put-down tune—is thrilling, with a driving fuzz-tone guitar riff and yelped lyrics like “I’ll give you rats and five pieces of gum, and then you’ll realize I’m not a bum.” It sounds like the early Rolling Stones fronted by the treasurer of the science club.

Nicholls owned a label as well as a studio, and in late 1966 he released the two songs as a 45. The band thought “Diamonds, Rats, and Gum” was the obvious hit, but a deejay at KRIO chose to play “Broken Hearted Lady,” which began climbing the station’s chart, eventually making it to number 23. The Souls capitalized, playing more gigs than ever, becoming, for a few months, teenage rock stars in the Valley. Lott says, “We thought, ‘We’re on our way to somewhere’—we didn’t know exactly where.” Their careers culminated at the South Padre Pavilion on Memorial Day 1967 with their biggest show ever. “The place was jam-packed with four hundred fans,” Smith told me. “It was mayhem.”

And then it was over. By the end of the summer of 1967, the Summer of Love, bands such as the Doors, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Jefferson Airplane, and Cream had taken control of pop music, and the Souls’ simple rock and roll was suddenly old-fashioned. Lott and Smith liked the new, more sophisticated sounds, but Hausman didn’t. “As a band it wasn’t happening anymore,” says Smith. “We started getting fragmented.” Hausman left, and by the end of the year the band had fallen apart. The Souls were history.

The swinging sound of young Texans

From 1964 to 1967, the story of the Souls played out in nearly every city and town in America: Boy hears Beatles. Boy wants guitar. Boy starts band. By my estimate, of the 73 million people who saw the Beatles on Ed Sullivan, some 73,000 started bands. By the mid-sixties Texas had thousands of teen rock and roll groups, many with Anglophile names like the Royal Knights, the Cambridge Lads, and the London Teens. They dressed like the Brits, grew their hair long like the Brits, sometimes even affected accents like the Brits. They wanted to be the Brits, not just play their music, which they did by learning the repertoire of the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, and the Animals. Many learned those songs in the garage, which eventually gave the genre its name: garage rock.

Texas garage rock bands played all over the state, at parties, church socials, dances, and an increasing number of teen clubs, which opened to meet the demand of the new youth movement. In every city, radio deejays spun songs by the boys next door; on low-budget TV shows local groups sang or lip-synched their songs of angst and anger. Fort Worth in particular had a thriving scene, with many Stones-y bands, such as the Jades and the Cynics. Dallas had its share of rough boys but also had many garage groups that jangled like the Byrds, bands such as the Chessmen, the Novas, and the Penthouse Five. Houston and Austin developed early psychedelic scenes with bands like the 13th Floor Elevators, the Lost and Found, and the Golden Dawn. Lubbock was home to the Heart Beats, one of the only all-girl bands (who formed in music class and eventually won a national TV contest), and Levelland produced the Sparkles, who recorded one of the era’s greatest songs, the angry “No Friend of Mine.” In Tyler, dozens of East Texas groups like Mouse and the Traps recorded at Robin Hood Studios, then released 45 rpm records on homegrown labels.

I’ve been a fan of garage rock ever since 1973, when I was a teenage boy myself and I bought a copy of Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From the First Psychedelic Era, a two-record compilation of American garage bands that included two Texas acts, among them Mouse (“A Public Execution”) and the 13th Floor Elevators (“You’re Gonna Miss Me”). I loved the raw, simple music, full of fuzz-tone guitar, keening organ, primitive drums, snarling vocals, and lyrics about lying girls. I wasn’t alone; Nuggets went on to become one of the most important albums in rock history, inspiring everyone from the Ramones and the Stooges to current bands like the Strokes and the White Stripes. These days garage rock is more popular than it ever was in its heyday, and not just in the U.S. Bands like the Raveonettes, from Denmark; the Hives, from Sweden; and the 5.6.7.8’s, from Japan, carry on the simple fuzz-tone tradition.

Groups that made it onto Nuggets have achieved rock immortality. But what happened to all those other garage bands, the guys who recorded songs, proudly pressed them up as 45’s, sold them at shows, heard them on the radio once or twice, had a brief period of crazed fame—and then went on to college or Vietnam or a career and a family? What happened to all that music? And all those boys?

I did some digging, through vinyl and CD compilations as well as Web sites where garage rock fanatics rescue long-lost bands from obscurity and post forgotten 45’s. What I found was that Texas rock and roll—from Doug Sahm through ZZ Top and on up to Spoon—has a secret history, one as weird and exciting as that of any other Texas music genre. Though the state’s original garage rock era was a brief, three-year period, it was a frantic one, with hundreds of teen bands making records. The great lesson of rock and roll is that anyone can make music, to which one must add the obvious and necessary corollary that not everyone has talent. But while much garage rock is amateurish, that’s part of its essential charm; by its very nature, some of the best garage rock demonstrates just how wobbly it feels to be a teenager.

I found plenty of stories like the Souls’, stories of young Texans who gave it a shot and then gave up. And I found plenty of boys who never quit, who became actual rock stars, grown-ups like Billy Gibbons, Don Henley, Gary P. Nunn, Jimmie Vaughan, and David Lott’s old bandmate Mitch Watkins, who plays lead guitar for Lyle Lovett.

I found plenty of derivative, dull, and—especially as the Summer of Love wore on—overwrought psychedelic music. But I also found songs that with a little luck would have been national hits. Listen to the driving guitar riff of “It’s a Cry’n Shame,” by the Gentlemen, as visceral as that of “Satisfaction.” Listen to the soaring chorus of “My Time,” by the Golden Dawn, as grand as that of “Gloria.” Listen to the chiming harmonies of “William Junior,” by the Novas, as sublime as those of “I’m Only Sleeping.” It’s the sound of Texas rock and roll in all its youthful glory, before moving from the family room to a room of one’s own. It’s the sound of innocence, before experience came along and screwed everything up.

Hey, Man, Let’s start a band!

Sixties bands began with boys on the block. Take the Riptides, from Corpus Christi. The group was started in 1964 by a bunch of fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds who lived in the same neighborhood. One of their passions was surfing; the other was playing the instrumental guitar songs of the Ventures and Dick Dale in a room the rhythm guitarist’s father had built onto the family garage. (In Texas, the extreme temperatures often made it impossible to play garage rock in a garage. “They should have been called den bands,” says Bill Bentley, a drummer in a number of sixties Houston groups. “All the bands I knew, the garage was too hot.”) The Riptides all liked the British Invasion bands, but none of the members could sing—and to sound like the Beatles or the Stones you needed melody and harmony, not just guitar riffs. Eventually Chris Gerniottis, a kid from down the street who was two grades behind the others, started hanging around their practices. Gerniottis had been singing since he was eight, and the band decided to hand him a microphone. By then the British Invasion was in full force, and the boys could resist no longer. “We tried to be English in almost every way,” Gerniottis told me. To begin with, they changed their name to the Zakary Thaks, which seemed surly and genteel at the same time, like Brian Jones wearing leather and lace.

“The Stones were as cool as you could get,” says Gerniottis, “though the Yardbirds were our favorite band. They dressed the way they wanted to onstage, their guitars were all fuzzed out, and they were cocky—a perfect mind-set for a teenager.” The Beatles were the face of the revolution, but when it came time to actually play songs, most garage bands covered the Stones, Them, the Kinks, or the Yardbirds. Partly this was because the Fab Four’s songs were slick and complicated, full of augmented chords. But there was also the cool factor. The Beatles were polite moptops. The Stones sneered. “Satisfaction” was so much hipper than “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

The Thaks had puny amps and cheap guitars, and every day they practiced after school. The drummer, Stan Moore, was a taskmaster and made them run through the songs over and over. The band learned as many of the Brits’ songs as they could, tunes like “Play With Fire” and “You Really Got Me.” They played teen clubs in Corpus, then worked their way up to venues like the Carousel, which had teen dances on Sunday afternoons, and the Dunes at Port Aransas. Sometimes they played one set, sometimes three. The most important thing: Make the kids move. “At the start it was all dancing,” Gerniottis explains. “You learned as much dance stuff as you could handle.”

All garage bands evolved this way. (Their English heroes had done the same thing, spending several years honing their chops by covering American blues and R&B artists.) Fort Worth had the most active scene; promoters began slapping the word “a-go-go” onto any place where teenagers could gather and dance to rock music with, of course, go-go dancers. Action A Go-Go was held at the Sycamore Park Recreation Center, Holiday A Go-Go at the Holiday Skating Rink, Teen A Go-Go at the Round Up. In Beaumont, bands played the Rose Room at the Hotel Beaumont or the Crown Room at the King Edward Hotel. In San Antonio Gerniottis remembers Sunday shows at the USO Club behind the Alamo for Air Force recruits just out of boot camp. A couple bands talked the principal of Dallas’s Bryan Adams High School into letting them play concerts in the girls’ gym on Friday mornings from seven to eight. Out in the country, bands booked shows at VFW and Knights of Columbus halls and on courthouse lawns.

Many groups dressed exactly like their British mentors. The Gentlemen wore ascots and Beatle boots. The Jades dressed in black suits with skinny ties, as the Stones did (leader Gary Carpenter sang just like Mick Jagger). Other groups went further: The Outcasts, of San Antonio, wore silver lamé jackets, while McAllen’s Marauders wore black turtlenecks, off-white slacks, leopard-skin vests, and Beatle boots. (Later, they sported the same sort of granny glasses John Lennon wore, even though, as guitarist Murray Schlesinger admits, “We didn’t need them.”)

The most important facet of their image, of course, was their hair. The Jades’ business card promised “Long Haired Musical Entertainment!” And though at night the kids could fool themselves into thinking they were in swinging London, in the light of day they still had to abide by a dress code. David Smith was sent home several times for his Beatles do. “The assistant principal called it a ‘subversive haircut,’” Smith says. The members of the Barons were kicked out of their Fort Worth school and wrote a song about it, called “Live and Die”: “Live and die, that’s all I’ve gotta do. I can wear my hair long if I really want to.”

The Thaks got away with their Brian Jones haircuts by going to a local barber who cut their hair in a special way. “During the day at school we could slick it back with Dippity-do or VO5,” Gerniottis says. “Then, when we got home, we washed it and Beatled it out.” Eventually, though, all the Thaks but Gerniottis were booted from Carroll High for their long hair.

Goin’ to a-go-go

Just as their British idols had tired of playing other people’s songs and started writing their own, so did the Americans. “We wanted to make records,” says Kenny Daniel, “like our heroes.” Daniel was the singer in Kenny and the Kasuals, a Dallas group that got its start playing the Lamplighter, a motel with a pool where bands entertained at weekend parties. Another teen, Mark Lee, was convinced that they could be the American Beatles—if he could be their manager, their Brian Epstein. In the wide-open Texas of 1965, every city had impresarios like Lee, guys who started labels, produced records, and managed bands. Daniel says, “He researched the Beatles and tried to do the same thing with us. He dressed us up in white satin pants and introduced us to Highland Park media. We bought all new Vox equipment, because that’s what the Beatles used.”

Most important, Lee took them into the studio to put out a record on his label, Mark Records. Technology, which had helped make electric guitars cheap, was also making it easy to produce a 45. There were studios all over the state, and the Kasuals did sessions at several in Dallas. Their biggest hit was something of a happenstance. After recording a song called “Things Gettin’ Better,” the group had an extra hour of studio time, so they quickly wrote another song, with Lee scribbling some lyrics on a piece of paper and guitarist Jerry Smith stealing a riff from an obscure Kinks tune. The result was “Journey to Tyme,” a garage classic, with a fuzz-bass intro, a soaring chorus, and vaguely psychedelic lyrics (“I’m on my way down kaleidoscope path”). The band was friends with Jimmy Rabbit, the deejay at powerful local station KLIF who introduced the Beatles when they played in Dallas in 1964. Rabbit came to the studio, fell in love with the song, took an acetate back to the station, and played it on the air. The phones lit up, and within weeks “Journey to Tyme” was a hit in Dallas, eventually climbing to number six on the local charts.

In 1965 and 1966 local deejays had the freedom to play what they wanted. In Fort Worth, KFJZ deejay Mark “Mark E. Baby” Stevens took a shine to the Elite, calling them “Fort Worth’s Fab Four” and playing their singles. “I can’t describe the feeling,” recalls the group’s singer, Rodger Brownlee, about hearing the Elite’s first song on the radio. “There’s your voice and your song coming out of the radio—it’s pretty heady stuff.” The Novas’ David Dennard says, “Deejays would take chances on things they liked, so a band could actually have a song played in two or three markets.” The Thaks’ “Face to Face” was a number one hit in Austin, San Antonio, and McAllen but failed to even get on the charts in Dallas and Houston, Gerniottis says.

Every city also had a TV show, a local version of American Bandstand. Kenny and the Kasuals were regulars on Sump’n Else, on WFAA, in Dallas. Along with bands like the Briks and the Novas, they lip-synched to their songs while go-go girls danced alongside. There were three shows in Fort Worth: Panther A Go-Go, The Mark E. Baby Show, and Hi-Ho Shebang. San Antonio had Swing Time, Houston had The Larry Kane Show, and Corpus had Teen Time.

All the exposure led to more gigs farther from home. The teens would load up the family station wagon and maybe a U-Haul trailer and hit the road for the weekend. “There were a lot of teen clubs between Abilene, Midland, and Lubbock,” says Wayland Huey, of Abilene’s the Livin’ End. The Novas used a hearse to get to their gigs in Wichita Falls and Fort Worth. The Thaks were more successful than other bands and would tour all over South and Central Texas, doing free shows at the USO Club in San Antonio and getting paid at the Pub, in Hondo, and the Shaft, in Devine.

It’s easy to forget how conservative Texas was in the mid-sixties, especially in response to all the changes going on in the rest of the country. The long-haired teenagers were refused service at restaurants and gas stations and cursed at. “We got called a lot of names,” remembers the Novas’ Dennard. “‘Fag.’ ‘Queer.’ And our hair was barely over our ears.” Ronny “Mouse” Weiss, of Mouse and the Traps, says, “We had swords pulled on us, and guns. I kept a shotgun in my car.” Gerniottis says that certain places were rougher than others: San Antonio, Victoria, and little Rockdale, north of Austin. “Rockdale was a major town for rednecks,” he says. Once, in 1966, the group did a show at a dance hall there and afterward went to a late-night cafe. “When we walked in, there was one other person there, a cowboy sitting at the counter, and he casually strolled over to the pay phone, made a call, and sat back down. By the time we finished eating, the place was full of rednecks and cowboys, staring at us and just waiting for us to say something. They were saying things like, ‘I bet they have to squat to pee,’ but not to our faces. We said, ‘Let’s get out of here,’ and walked to the car. But Pete Stinson, who was the one guy who could have taken them on, took his time, stopped at the door, turned, and gave them the double finger—he flipped them off—then ran out. We knew he was going to do something like that, so we had started the car and left the door open. He dove in, and they were all running out and piling into their trucks, and we all flipped them off and took off, floored it, and they followed us for quite a ways before turning around. That was the last time we played Rockdale.”

For the most part the teenage boys weren’t aware that they were part of a national counterculture—they were just chasing thrills, fame, and girls. But the U.S. was a different place in 1967 than it had been in 1964, and the thousands of long-haired teens playing rock and roll had something to do with it. Down in the Rio Grande Valley, garage rock may have helped ease the pains of integration. Most Texas garage bands were made up of white suburban kids, but in the Valley, many bands had a mix of Anglo and Mexican American teenagers. One of these bands was the Cavaliers, fronted by the charismatic Javier Rios, the boy who played “Twist and Shout” and “La Bamba” at that McAllen junior high assembly. “When I joined the Cavaliers,” he says, “we played the American Legion hall, and there was not one Hispanic male in the crowd. But slowly, more and more Hispanics started coming to shows. And when we played in Western towns like Falfurrias and Victoria, where everybody but us wore cowboy hats, they accepted us because they liked our music. I’m proud to say we had a little something to do with breaking down the barriers. People started looking at the talent, not the skin.”

The Zakary Thaks’ lead guitarist, John Lopez, provoked a very different reaction. “San Antonio was the only town where John’s ethnicity would occasionally be an issue,” says Gerniottis. “And it was the Hispanics who showed animosity. We had a few beer bottles thrown at us. After our first few gigs there, we came up with the idea of introducing John to the audience as being from Hawaii. Although it was meant as more of a joke to keep ourselves amused, it actually seemed to do the trick.”

The psychedelic sound of young Texas

Garage rock’s time was brief, as befits any period of teenage innocence, and it was killed off by several things. The draft sent many teens off to war. After playing a final Dallas show, Kenny Daniel caught a bus to Fort Polk, Louisiana, the next morning and wound up in Vietnam. A lot of kids went to college, either to escape the draft or just because that’s what middle-class kids did. But the main culprit was evolution, or maturity, or whatever you want to call the trend to psychedelic music. The Beatles, Stones, and Yardbirds were all doing it, as were pioneering musicians like Jimi Hendrix and Cream: composing intricate songs, playing drawn-out jams, and writing lyrics about things besides girls.

One of the leaders of the trend, whether he knew it or not, was a Beatles fan from Austin named Roky Erickson. At fifteen he wrote “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” the song from Nuggets, and in 1965 was singing it in a garage band called the Spades. But in November a group of slightly older musicians stole Erickson away. They were led by Tommy Hall, an LSD freak who saw himself as a guru. Hall talked the band into proselytizing his vision—they would take LSD before performances, then “play the acid” and convey the experience to the audience. The group’s business cards called their droning music “Psychedelic Rock”; they took the name the 13th Floor Elevators, because, as Erickson said, “If you want to get to the thirteenth floor, ride our elevator.”

The next two years were a bumpy ride of drug busts and bad trips. The Elevators became one of the state’s most popular bands; their version of “You’re Gonna Miss Me” got them on American Bandstand and the Billboard charts, where the song rose all the way to number 55. Their raucous, unpredictable live shows were packed, and other Texas bands began copying their sound and vibe. Houston’s the Lost and Found and Austin’s the Golden Dawn recorded albums for the same Houston label, with similar psychedelic cover art. Gerniottis remembers the Thaks doing four shows with the Elevators. “That was a spark for us,” he says. “ ‘Oh, now we see.’ We took a right turn, went a little more complex. By the summer of ’67 we were doing songs that were totally undanceable—Country Joe and the Fish, Jefferson Airplane’s ‘3/5 of a Mile in 10 Seconds,’ ‘My Back Pages.’ We were exploring.”

By then, everyone was playing the new hip sounds. “Psychedelia affected everything,” Dennard says. “The way we looked, our hair length, the colors we wore. I was into swirling music—Hendrix, Cream, Sgt. Pepper. I was pushing for that, but the rest of the band was not into it. Though we did start doing more jamming. Before that all the parts had been arranged.” Huey says that out in Abilene, “A lot of our songs got longer. We didn’t call it ‘psychedelic’—we didn’t know what it was called. Though we did make a strobe light out of a fan.”

As the songs got longer, they got more serious and complicated, losing the snap and humor of the halcyon days of the previous summer. Waco’s Gaylan Ladd recorded “Repulsive Situation,” which included these lyrics: “Trying to find a repulsive situation. All you got to do is look across this nation.” The Nomads, from Houston, had a song called “Mainstream,” which sounded like a hippie caricature: “The new generation is based on love and imagination . . . Let the new generation show you that the lovin’ thing freely is the only way.”

Unfortunately, the teens had grown up.

Get back to where you once belonged

By the Summer of Love, most of the world had moved on to “Light My Fire” and “A Whiter Shade of Pale.” Plenty of bands, though, especially those playing in the hinterlands, didn’t get the memo about the end of garage rock. In Odessa, the high school sophomores of Knights Bridge recorded “Make Me Some Love,” a simple four-chord garage song with organ and furious feedbacking guitars about, well, “the way you hold me, the way you touch me.”

And in Bridgeport (population approximately 3,500), fifty miles north of Fort Worth, the Green Fuz created “The Green Fuz,” one of the greatest garage songs of all, a song so poorly played and horribly recorded it’s a wonder the band ever released it. The Green Fuz had formed in 1967 and was named for fifteen-year-old guitarist Les Dale’s green fuzz box. They played at parties, teen clubs, skating rinks, and county fairs and at some point in 1968 decided to make a record. They had two original songs, one of which, “The Green Fuz,” Dale had written in 45 minutes. There were no studios nearby, so they recorded in an empty cafe owned by Dale’s mother at the intersection of two farm-to-market roads. The band’s producer, Shorty Hendrix, set up a tape recorder and laid a couple microphones on a table nearby. The cafe was made out of stone, so the acoustics were horrible; the boys had to keep turning the PA system down, and they had to muffle the bass drum by stuffing it with pillows. Because of the heat and humidity they also had a hard time keeping the guitars in tune. But still they pushed on, recording “The Green Fuz,” one minute and 59 seconds of primitive, mind-blowing noise. The drums rumble as if they’re being played next door, the bass is barely audible, and Randy Alvey’s vocal is high and scratchy: “Here we come, we’re coming fast. / All the others are in the past. / Jump to your feet, let us catch your eye / We’re the Green Fuz.”

Maybe it’s the simple singsongy melody, maybe it’s those needy words of teen bravado, maybe it’s the limitations those boys were pushing against, but “The Green Fuz” is a work of art in the same way “Louie Louie” is a work of art. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony sounds like God. Ravel’s Boléro sounds like sex. “The Green Fuz” sounds like youth—out of tune, out of time.

The band pressed five hundred copies of the 45 and released it in 1968. “We were so sure we were going to be rock stars,” Dale told me. “We were less than happy with the way it sounded, but on the other hand, we had a record. No one else in town did. The people at the Dairy Mart, where everyone hung out, put it on the jukebox. For a while we were the rock stars of Bridgeport. But nobody outside of Wise County ever heard it.” The group broke up a year later, and four of the five members eventually went into the Navy, including Dale, who later married, had three sons, and rarely thought about “The Green Fuz.” In 2006 he returned to Bridgeport for the first time in thirty years and located the band’s old rhythm guitarist, Jimmy Mercer. “He told me, ‘I need to show you something,’” Dale recalls. Mercer pulled out a copy of an album called Psychedelic Jungle, by the Cramps. Dale had never heard of the Cramps, who were famous as the trashiest, kitschiest punk band of the seventies and eighties. This 1981 LP was their best, full of covers of eccentric old American garage rock and rockabilly. And the very first song: a magnificent version of “The Green Fuz.” The song had become an underground hit, known and loved by punk rock weirdos everywhere.

“It’s hard to wrap your head around something like that,” Dale says. “A song you wrote at fifteen has a worldwide cult following.” After the other three members signed on (all of Dale’s bandmates thought he had been killed in Vietnam), the band reunited at the oldies revival show the Ponderosa Stomp, in New Orleans, in 2008. They performed some of their covers and played “The Green Fuz”—twice—to a fanatical crowd. “It was like we were sixteen again,” Dale told me.

The Green Fuz aren’t the only sixtysomethings enjoying a fillip of sixties-rock fame. Vintage garage rock has become extremely hip over the past decade, with collectors (many from Europe) scouring garage sales for rare 45’s. In January of last year David Lott got a Facebook message from David Smith, whom he hadn’t heard from in forty years, telling him that a copy of the Souls’ “Diamonds, Rats, and Gum” had sold on eBay for $1,225.

Many of the Texas bands have reunited. The Thaks did a handful of shows in 2005 and 2006—without drummer Stan Moore, who died in 2000—and then stopped. “You can’t replicate the magic,” says Gerniottis. “There was an obvious gap in the sound without Stan there. He was the heart and soul of the group.” Kenny and the Kasuals have turned nostalgia into big business, playing some twenty shows a year, mostly private parties and corporate events (Jerry Jones is a client). The Novas play occasionally, though Dennard says, “We do it for the fun, not money or fame and certainly not for the sex anymore.”

Dennard is almost sixty but finds that playing with his old friends in the Novas takes him back to being sixteen, when the simple things were the only ones that mattered. “It’s so fun to make that sound,” he says. “It’s so much fun to be in a garage when those instruments clash together till you get something new. If you get a beat going and you all find a key and someone has something to say and if you have a guitar player and he’s mad at his parents or society or his school and he’s taking it out on his instrument—you get a great garage moment. The teen angst is coming through. It’s kind of spiritual. It makes you fly. You’re in your moment, mapping a way ahead of yourself.”

10 Famous Musicians

Who got their start in Texas garage bands.

Doyle Bramhall solo artist, songwriter (The Chessmen, Dallas)

T Bone Burnett producer, songwriter, solo artist (The Loose Ends, Fort Worth)

Roky Erickson solo artist, songwriter (The 13th Floor Elevators, Austin)

Billy Gibbons ZZ Top (The Moving Sidewalks, Houston)

Don Henley the Eagles, solo artist (The Four Speeds, Linden)

Gary P. Nunn Lost Gonzo Band, solo artist (The Sparkles, Levelland)

Dan Seals England Dan and John Ford Coley, solo artist (Theze Few, Dallas)

J. D. Souther solo artist, songwriter (The Cinders, Amarillo)

Jimmie Vaughan Fabulous Thunderbirds, solo artist (The Chessmen, Dallas)

Mitch Watkins Lyle Lovett and His Large Band, solo artist (The Marauders, McAllen)

Texas Nuggets

20 garage rock songs you must hear before you die.

“Look in Your Mirror” The Merlynn Tree, Austin

“My Time” The Golden Dawn, Austin

“You’re Gonna Miss Me” The 13th Floor Elevators, Austin

“The Green Fuz” Randy Alvey and the Green Fuz, Bridgeport

“Face to Face” The Zakary Thaks, Corpus Christi

“A Taste of the Same” The Bad Seeds, Corpus Christi

“It’s a Cry’n Shame” The Gentlemen, Dallas

“Journey to Tyme” Kenny and the Kasuals, Dallas

“Love for a Price” Kempy and the Guardians, Dallas

“William Junior” The Novas, Dallas

“You’re Gonna Be Lonely” The Chessmen, Dallas

“I’m Blue” The Rising Sons, Fort Worth

“Little Girl” The Jades, Fort Worth

“Live and Die” The Barons, Fort Worth

“Air conditioned man” Thursday’s Children, Houston

“I Can’t Believe” Neal Ford and the Fanatics, Houston

“No One Wants Me” The Actioneers, Houston

“No Friend of Mine” The Sparkles, Levelland

“Diamonds, Rats, and Gum” Christopher and the Souls, McAllen

“A Public Execution” Mouse, Tyler