This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Like pilgrims entering a shrine, seven men clutching scrolls and sketchbooks filed past the stone colonnades, past the art deco frescoes depicting the history of Texas, and into the vaulted cathedral of the Texas Commerce Bank lobby. To the bank employees who arrived early on this chilly December morning in 1977, the seven must have seemed an unremarkable group. Dressed in the muted blues and grays of business couture, the strangers could have been a contingent of pension-fund managers or, for that matter, the directors of a sausage company coming in for a loan.

But upstairs, in a theater outfitted especially for the occasion, the master builders of Houston were waiting. Ben Love, chairman of Texas Commerce Bancshares, and Gerald Hines, investment builder, had paid $105,000 for the privilege of watching these seven men perform, and within the next twelve hours they hoped to get their money’s worth. The Building, as it had come to be called over the past ten years, would take its final form that day.

Ben Love already had some idea of what The Building should look like. It would have to be tall, for one thing, taller than any other bank building in Texas. Ever since Love had become chairman of Texas Commerce Bancshares in 1972, his great ambition had been to run the biggest bank and the biggest bank holding company in the state. That goal seemed almost within grasp, but a big bank needed a big building. He wanted a landmark, something to transform his growing empire of paper into a statement in brick and mortar.

Love also knew what he didn’t want. His building would not be another colossal Kleenex box in glass and steel, the style that now seemed to dominate the freeways of Houston and much of its central business district. He wanted this building to be “a real gift to Houston,” he told his friends, something that would retain its grandeur far into the future. Ben Love wanted the best architect money could buy.

Gerald Hines was happy to oblige. Hines, who has influenced the shape of Houston’s skyline more than any other person, had promised Love that he would get his architect. Making their way to the theater where Love and Hines waited were the seven men whom Hines considered to be doing the most exciting architectural work in the world today. Among their terrestrial monuments were such landmarks as the World Trade Center, the Astrodome, the NASA space complex, the Dallas City Hall, and much of the grandiose architecture of Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf sheikdoms.

Taken together, the seven men who visited Texas Commerce that day had some two hundred years of architectural experience and represented firms that had designed more than five thousand buildings in the U.S. and foreign countries. For the trouble of making a site study, a set of drawings, and a model of his proposed building, each one would receive $15,000 and the privilege of giving a one-hour presentation for Love, Hines, and selected senior officers from the companies of both men. One of the seven would leave with a contract to design the biggest office building in the Southwest, part of a construction project that would cost about $140 million.

If any of the competing architects had stopped in the lobby to admire the three-story walls of Siena travertine, they would have noticed an oversized portrait of a white-haired man, thin-lipped, square-jawed, standing erect with his hand thrust into the trouser pocket of a dapper blue suit. Jesse Jones had three great passions in life—building, banking, and boosting Houston—and his presence in the lobby that he designed as a “monument to the New South” seemed altogether fitting on a day such as this. Two decades after his death, Jones’s portrait was still the only object drawn on a scale commensurate with his Romanesque banking hall. The painting had become such an integral part of the great room that customers were known to complain to the board of directors whenever the icon was taken down for cleaning. A less admiring relative of Jones’s once said of the portrait, “It was the only time in his life that Jesse had his hand in his own pocket.”

Jones in death may have been bigger even than Jones in life. This, too, was fitting, for the ghost of Jesse Jones would influence the location, the size, and even the design of Ben Love’s new building.

A Tale of One City

Founded by land speculators, ruled for a century and a half by developers of one sort or another, Houston is less an accident of geography than a concerted plot by real estate brokers. It is and always has been a city of builders, and hence it’s a place peculiarly defined by its buildings. Ben Love’s is the newest one, the biggest, and by all accounts the next candidate for lord of the mercurial Houston skyline. When finished, the Texas Commerce Tower will be the tallest of those buildings, and the seventh tallest in the nation, looming twenty stories above the next highest structure in Houston. It will contain 3.1 million square feet of office space. Without doubt, it will forever alter the appearance of downtown Houston.

The erection of Houston business monuments is, of course, nothing new. In 1946, as convenient a date as any to mark the beginning of Houston’s modern frenzy of building, Oveta Culp Hobby, then a director and now the publisher of the Houston Post, looked at the pell-mell construction and sighed. “I think I’ll like Houston,” she said, “if they ever get it finished.”

It took the Italians thirty years to build Florence in the heyday of the Renaissance. The present-day appearance of Paris was achieved in fewer than forty. Yet only within the last fifteen years has Houston even begun to erect the kind of public building that appears to be worth at least a century of use, and given the aggressive land annexations of the city council, Houston may not assume any permanent form until well into the next century. In fact, it is this very formlessness that has given the city its most notable architectural landmarks. The Galleria, the Shamrock Hotel, Greenway Plaza, the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center—all were created out of architectural voids, dictating their own landscapes and shaping the growth and development of their areas by the simple fact of their existence. Only in the central business district, laid out on a grid hand-drawn by the founding Allen brothers in 1836, were the landmarks of commerce forced to make some compromise, however small, with history.

A time-exposure photograph of downtown Houston begun in 1965 and continuing until the present would reveal a rapid succession of vertical thrusts, each new building challenging the previous one in height, mass, and presumably expense. You don’t have to be very old to remember a day when the ornate Esperson Building, its circular cupola supported by Corinthian columns, was, though not the tallest of downtown buildings, nevertheless the unchallenged queen. Today, like a gentle grandmother surrounded by an army of virile young men, its modest 27 stories are all but obliterated by its gargantuan neighbors. Even now, as a 75-story tower arises from a vast hole in the ground near the Convention Center, other men are no doubt scheming to challenge its preeminence. Mrs. Hobby, needless to say, is still waiting.

The Plots of Mr. Jones

Ben Love was a boy of seven, just starting school in Paris, Texas, when the story of his building project began. On the bleak Sunday morning of October 25, 1931, Jesse Jones sat brooding and plotting in his penthouse suite atop the Lamar Hotel. The year had been the worst in history for American bankers, and now it appeared that the Houston banks had less than 24 hours to head off a total financial collapse. It was obvious to Jones and to most Houston businessmen that two banks—Houston National and Public National Bank and Trust—were so frail that they would not be able to open their doors on Monday morning. That alone would be enough to set off a panic, but Houston National’s principal owner was no less than the governor of Texas, R. S. Sterling.

Jones set out to gather together every banker in the city. The top floor of the tallest building in Houston was the only place he could think of that ensured total secrecy. Jones had built the 35-story Gulf Building in 1928 as a home for the young Gulf Oil Company and his own tiny National Bank of Commerce, and he would always consider it the crown jewel of his many building projects. For its site he selected the most historic block in Houston, the very place where the Allen brothers had built their own house in 1836, and he used the most expensive limestone, French marble, and Italian travertine available. From the observation deck he installed on the roof, Jones could look out at the largest part of his empire: he owned more skyscrapers than anyone in history, including fifty office buildings in Houston, most of the skyline of Fort Worth, and several of New York City’s tallest buildings. His own office was in the modest ten-story Bankers Mortgage Building, the first office skyscraper built in Houston—by Jones, of course, in 1908. Clearly, if anyone had a stake in the survival of Houston’s banks, it was Jesse Jones.

At two in the afternoon that day, every bank chairman and president in Houston crowded into the executive suite of the Gulf Building, all of them pledged to absolute secrecy. Then, as the story was later told by Jones’s official hagiographer, Bascom Timmons of the Houston Chronicle, Jones’s simple eloquence and calm but grave demeanor almost singlehandedly saved the Houston economy. Actually, it would take Jones two full days to win the ensuing debate, and the first session—which lasted until five o’clock Monday morning—resulted in no more than an agreement to subsidize the two shaky banks for one day’s business. Then, as now, Houston thought of itself as the capital of free enterprise, and that meant to most of the bankers that bad management deserved failure. When the bankers met again on Monday night the two banks’ books had been examined, and it was apparent that a full $1.25 million would be needed to save them. Two of the most powerful banks—South Texas National and Union National—refused to help.

At this point Jones resorted to his two best assets: friendship and guile. Having been turned down by the president of South Texas, Jones hunted by phone until three o’clock in the morning for the bank’s chairman, his friend Captain James A. Baker. He found Baker vacationing in Bassrocks, Maine, where he roused him from bed, patiently reviewed the events of the past two days, and stood by while Baker summoned his president to the phone and virtually ordered him to put up his bank’s share of the money. The remaining dissenter, Union National, also capitulated after all its support had been eroded.

Jones didn’t stop there. By six o’clock on Tuesday morning, when the final documents had been drawn up by lawyers and accountants working through the night, Jones had contacted, in addition to the banks, the heads of Houston Lighting and Power, the gas company, Southwestern Bell, and Anderson-Clayton, the cotton merchants, all of whom consented to contribute a share. As a final flourish, Jones agreed that the National Bank of Commerce would take over the all-but-bankrupt Public National Bank—an institution that nobody wanted—even though Jones’s bank was the smallest in town. The banks remained open. Houston did not have a single bank failure during the Depression. And the two banks that were merged into others managed to pay off every depositor.

The bankers’ prolonged caucus, invisible to the public, had not gone unnoticed in the other American financial capitals. A few months later Jones got a call from Washington, where he would spend the next decade directing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Repeating his performance on a national stage, Jones personally handed out more than $50 billion in government loans to American banks and sat in on many more all-night sessions in the financial centers of the country.

Before leaving for the capital Jones solved one other problem that had troubled him for some time. Despite the modest size of the National Bank of Commerce, Jones was convinced that history and geography, with a little help from his own selective building plan, would conspire to make it the most desirable bank in Houston. It was located, first of all, on one of the best plots of real estate in the city—one block south of Texas Avenue, the widest street, and facing Main Street. Just a block north was Jones’s own Rice Hotel, the center of society, politics, business, and nightlife, and a block to the west of the Rice was Jones’s newspaper, the Chronicle. The development of Houston would undoubtedly follow the north-south axis of Main, he reasoned, and his bank, located at the center of that axis, would become the prime financial location.

All of this was logical—especially since Jones had just constructed the spectacular Gulf Building to house the bank—but he still had one great fear. The block between the Rice Hotel and the Gulf Building—known as Block 68—was devoid of major office buildings, and the land was not particularly expensive. Suppose someone decided to open a bank at Texas and Main, directly across from the Rice Hotel, to eclipse the Gulf Building as the northern anchor of the financial district. Jones would suffer from the very success of his own buildings.

So he set out to see that this fear would never be realized. Fortunately, the largest part of that block, and the part facing Main Street, had recently gone into probate. Originally owned by the McAshans, an old Houston family, it was about to be carved up by a judge among seven of the McAshan heirs. No one knows exactly how Jones did it, but when the judge had finished, Jones owned two of those shares—one at the corner of Capitol and Main, directly opposite the Gulf Building, and another in the exact center of the block, also fronting on Main. Moreover, the final judgment had sliced the extensive property into small parcels ranging from 10-foot to 25-foot frontages, too small for any significant building project. At Texas Commerce, where the story is told by senior officers with obvious relish, Jones is also said to have engineered the further subdivision of the rest of the block, until most of the lots were owned by his friends and the whole of it had fourteen separate landlords. After the dealing was complete, Jones breathed easier. “Nobody,” he said, “will ever be able to put that block together again.”

Mr. Whitmore Meets Mr. Love

The banking heirs of Jesse Jones had little occasion to worry about real estate. If not quite the worst of times, the years of the middle sixties were still ridden with anxiety for the officers and directors of Texas Commerce Bank. Once the biggest bank in Houston, Texas Commerce had fallen to an embarrassing third place, and as the rest of the nation’s banks enjoyed an economic boom fueled by a foreign war, it languished because of its preoccupation with internal politics. Its once placid boardroom—ruled by the iron will and courtly manner of Jesse Jones until his death in 1956—was now the scene of petty squabbling among directors rendered indecisive by a merger gone awry.

The immediate cause of the dissension was the 1964 decision to merge the National Bank of Commerce, as it was called then, with the much smaller and much younger Texas National Bank. Texas National’s balance sheet was only 60 per cent the size of the larger bank’s, but there was a more compelling reason for the marriage. Jesse Jones’s bank had grown old—so old that when the board of directors passed a mandatory retirement rule in 1966, the bank lost twelve senior officers in a single day. Texas National, on the other hand, had a full stable of eager young officers ready to do battle with the larger First City National and Bank of the Southwest. Not surprisingly, the officers of Texas National wanted something in return for all that talent—namely, a significant share of the bank’s management. But the new Texas Commerce Bank board was heavily weighted, in both dollars and numbers, in favor of the old National Bank of Commerce people. The resulting tumult ended in the reluctant and bitter resignations of the new bank’s president, J. W. McLean, and vice chairman of the board, Dillon Anderson, both veterans of Texas National.

It fell to John Whitmore, a longtime employee who had begun his banking career as an assistant cashier, to assume the presidency, negotiate a temporary peace, and begin to build again. The bank was hardly anemic—no Houston bank could have been in the boom years of the sixties—and it had deposits of some $700 million. But with Jesse Jones ten years in his grave, the bank was forced for the first time in memory to actively promote itself. In 1956, the very year of Jones’s death, the second- and third-largest banks—City National and First National—had ganged up on the National Bank of Commerce by merging into a financial colossus newly christened First City National. With that single stroke, Jones’s rivals had virtually doubled the size of any previous Houston bank and taken a lead they have never relinquished. Led by City National’s Judge James Elkins, a friendly adversary of Jones’s, First City National would forever after be the archrival of Texas Commerce.

Whitmore drew a bead on First City and launched a hiring spree that reached into every area of the city’s business community. One of his early talent hunts uncovered a young man who had made his fortune selling gift-wrapping paper, then sold his company to Gibson Greeting Cards. In his latest incarnation, he had assumed the presidency of River Oaks Bank & Trust, a so-called neighborhood bank that he was turning into a money machine by stacking its board with his personal friends and encouraging them to get out and solicit business. They did—and the bank’s deposits increased by 75 per cent within a mere eighteen months. Here was a man, thought Whitmore, who knew how to do business in Houston. Whitmore invited him downtown and offered him a senior vice presidency. Ben Love took the job, and in 1967 the boom began.

Mr. Horne Gets an Idea

Howard Horne, a bearish, avuncular man with a gentle voice and a quick laugh, has a motto for his company: “Weather isn’t the most changeable thing on earth; real estate is.” The Horne Company has been trafficking in the real estate of downtown Houston for 54 years, ever since Horne’s father, W. A. Horne, brokered his first deal. Every executive in Horne’s firm has on his wall a king-size map of downtown Houston, divided into plats, with the names of all the owners penciled in. Chances are that someone in the company could tell you who each one of those people is, where he works, where he lives, how old he is, how long he’s owned the property, and how he feels about money in general and real estate brokers in particular. Most of those owners have, at one time or another, accepted a free lunch from someone at the Horne Company, sometimes just to perpetuate the friendships that are so necessary to the business. Howard Horne learned at a very early age that the broker’s best weapons are time and patience.

It was in 1967 that Howard Horne first had occasion to take a long, hard look at Block 68, bounded by Texas on the north, Travis on the west, Capitol on the south, and Main on the east. That square on his map had undergone few changes in recent years, but Horne had a tip that Home Title Company, which had been planning to build on that block, had reversed its decision and now wanted to unload a large chunk of land, 150 feet square, at the southwestern corner. It was by far the largest plat on the block and for years had been the home of Montgomery Ward, until that department store moved to the suburbs in the early sixties. The rest of the block held odd-shaped little lots of no particular interest. The old Milby Hotel, weathered and forlorn, stood on the northwest corner, at Travis and Texas. On Texas, directly across from the Rice Hotel, were a liquor store, a newsstand, and the most popular lunch spot in town, Kelley’s Oyster Bar. Along Main, on the eastern side of the block, were a dozen tiny shops, all of which had seen better days, including a haberdashery, a furrier, a drugstore, a National Shirt shop, the Felix Mexican Restaurant, Thom McAn and Hanover shoe stores, a toy shop, and two jewelry stores.

Horne was old enough to remember the row of stores as it had looked in the forties, when it was the prime retail location in all of Houston and the intersection of Main and Texas was perhaps the busiest corner in the state. In those days the shops catered strictly to the carriage trade, but now most of them were victims of suburban shopping malls and dealt in either secondhand goods or discount clothing. Horne had seen blocks like this before; they were all too common in downtown Houston in the sixties. Montgomery Ward’s evacuation seemed almost clairvoyant.

It is said that real estate is the art of finding a willing buyer and a willing seller and letting them make music together. This is not altogether true. In this case all that was needed was a willing broker.

Howard Horne was not yet ready to call on the fourteen owners whose properties made up Block 68. Instead, his eye continued across Capitol to the adjoining Block 81, where he saw, in large letters, the words “Gulf Building.” He picked up the phone and arranged an appointment with John Whitmore, chairman of Texas Commerce Bank.

Two Gentlemen Conspire

John Whitmore was skeptical, and he had plenty of reasons to feel that way. This was a critical year for the bank—deposits were growing again, profits were up, and yet the pattern of construction in downtown Houston seemed hopelessly out of the bank’s control. Whitmore, too, had noticed the abandonment of downtown by the big department stores, the proliferation of small loan companies and discount stores along once-grand Main Street, and he knew that sooner or later the bank would have to make a decision: either move south or stand and fight. Jesse Jones’s exalted vision of Texas Commerce as the northern anchor of a prosperous business district no longer applied. As early as 1956 the Bank of the Southwest had boldly moved into new quarters away from Main Street, and in 1963 everyone had been startled when the new Humble Building (now the Exxon Building) went up at Travis and Bell, on the extreme southern edge of the business district, a full nine blocks south of Texas Avenue. Following that were the Tenneco Building, Southwest Tower, Cullen Center, and the Houston Natural Gas Building—all away from Main, all far south of the bank.

Whitmore had the nightmare vision of an urban slum growing up right at his doorstep, its tentacles gradually encircling such venerable structures of the past as the Rice Hotel, his own Gulf Building, and, indeed, most of what Jesse Jones had spent a lifetime building. The continuing presence of his archrival, First City National, on a Main Street site just three blocks away was one of Whitmore’s few comforts. Another was the support of the Houston Endowment, a huge trust established by Jesse Jones’s will, which reemphasized its faith in the north end by financing construction of the Jones Hall for the Performing Arts at Texas and Milam in 1966.

Whitmore’s directors counseled him to be patient. Texas Commerce had lasted forty years on Main Street; it would weather this temporary shift. Banks may locate away from Main Street for a while, the directors said, but the forces of history and the price of land will bring them back to the geographic center of the business district. Whitmore decided to stand and fight—at least for a while.

Howard Horne was well aware of the thoughts racing through Whitmore’s mind. “This is one way to protect your investment,” he told him, gesturing toward the large plot once owned by Montgomery Ward. It was the obvious place for expansion—Whitmore knew the growth of the bank would demand more space—and it would also be a strategic location if northern downtown staged a comeback. But Horne had something else in mind, too. “I think with a little patience and work,” he said, “I can put that whole block back together for you.”

That block was Block 68, the very one that Jesse Jones had so skillfully carved into minuscule fragments. Whitmore had heard of Jones’s boast, too. Nobody will ever be able to put that block together again. Until Horne’s visit, no one at Texas Commerce had ever thought of the bank’s permanent home as being anyplace other than the Gulf Building. It would take several years before most employees got used to the idea of a new building—some don’t like it even now—but the germ of the idea originated on the day Horne showed Block 68 to Whitmore. Boxed in on the south by another office building, and on the west by the Houston Club, Whitmore had only one choice. If he wanted one of the adjoining blocks for expansion, it would have to be Block 68.

Whitmore, like all good bankers should, chose the course of caution. He would agree to buy the Montgomery Ward property, which seemed cheap at $47 a square foot, and he would agree to buy any other lots under two conditions: First, he told Horne, no one must know that the bank was the buyer. Second, the block must be assembled in order, working clockwise from the Montgomery Ward plot, so that the bank was not saddled with odd lots surrounded by property it couldn’t acquire.

Horne readily agreed.

Mr. Horne Employed

The Milby Hotel was not for sale. It took Howard Horne five minutes to learn that, and it took him three years to gain the confidence of Charles Milby. The Milby family had run the establishment at Texas and Travis for fifty years, and while it might not look like much today, it had a sentimental value and, after all, it did make money. How do you place a value on sentiment?

Sentiment, circumspection, recalcitrance, reluctance to discuss money—all of these things are common in the world of the Horne Company, and all have the same antidote: time. Horne was willing to wait, but every few months he managed to drop in on Charles Milby, sometimes for lunch at the Walgreen’s off the main lobby. Each time they met, Horne informed Milby that the value of his land had risen. And the value of the Milby Hotel was enhanced by the fact that its purchase by the bank would complete almost half the block, more than enough to build a small office building for expansion.

Business at the Milby—and, indeed, at the Rice—was not getting any better, and no one was affected more by the decline of northern downtown than the hotelkeepers in the area. It may have been this decline that broke down Milby’s resistance, but by early 1970 he began to show signs of weakness. A few more price increases and Horne was able to close the deal. For $60 a square foot—$13 more than for the Montgomery Ward property—Horne added the Milby Hotel to his conquests on Block 68. But his initial euphoria was quickly squelched. This was only the beginning.

Next on the block was a small building owned by the George P. Brown estate (no relation to George Brown, the founder of Brown & Root) and managed by Cleve Brown. Like most of the owners of property in the northern part of downtown, Brown represented the second generation of an old Houston family that had held the land since the nineteenth century. He was hardly inclined to sell it. He had no particular attachment to the liquor store and newsstand in the building, but Kelley’s Oyster Bar—that was an entirely different matter. Kelley’s was the first New Orleans–style stand-up oyster bar in Houston, and over the years it had become an institution almost as lovable as the Rice Hotel it faced. Howard Horne listened to story after story about the good old days at Kelley’s as he and Brown lingered over long lunches or sipped cocktails at the Capitol Club in the Rice Hotel. Eighty-two years old, Brown relished the past almost as much as he bemoaned the present, for even Kelley’s was not doing the business it once did. Still, selling the property was out of the question. It provided a steady income, it had been in the family for so long, and the capital gains tax on such a large sale would be devastating.

Jesse Jones used to say that doing business with unwilling partners was like trying to break a logjam. If one or two of them can be dislodged, the rest will follow in a torrent. This was how Horne felt about Cleve Brown. If he could get this building, the rest of the block might fall like a row of dominoes. That, and now the inevitability of a major Texas Commerce building project, were the only reasons he spent two years at the doorstep of a man who owned a mere 10,000 square feet of a city block.

Cleve Brown liked Howard Horne, and in the end that may have made all the difference. In late 1972 or early 1973, Horne called the bank with great news. Another deal was closed. For a mere $700,000—or $70 a square foot—they could have the Brown property. But this time it wasn’t John Whitmore who took the call. Ben Love, who had succeeded Whitmore as chairman in December 1972, had even more reason to covet Block 68. Love ordered his staff to draw up the check.

Mr. Love Grows Anxious

Poking up out of the giant map of Texas are 39 state flags in red, white, and blue, each one adorned with the name of a bank. The maps and flags are everywhere—in the lobbies of airports, on freeway billboards, scattered through the glossy pages of Texas magazines—bright symbols of the Ben Love era at Texas Commerce. Thanks to an amendment to the Federal Bank Holding act of 1970, ushering in the colossal holding companies of Houston and Dallas, Ben Love’s first decade at the bank was one of constant expansion and aggressive acquisition under the name of Texas Commerce Bancshares. Texas Commerce Bank remained responsible for 60 per cent of the holding company’s assets, but the new competition among the Big Four—the others being First International Bancshares of Dallas, Republic of Texas, and First City Bancorporation—meant that Love had more to worry about than his downtown Houston rivals. Three floors of the Gulf Building had to be converted to accommodate all the new employees of the holding company, and even then its rapid growth outreached the available space.

Now, in 1975, Love knew that The Building would have to come soon, not only for the extra space but for the kind of image-building necessary to promote the company into the next decade. A building is usually a bank’s only visible asset, and the Gulf Building, no matter how loved and venerated it might be, had begun to look like an elderly dowager in a city of vaulting steel. Love was afraid that the building might be hurting his recruiting—that many of those bright young Harvard MBAs and graduates of the Wharton School were dazzled by the big bank towers that were constructed during the fifties and sixties. When rumors circulated that First City National was planning a new tower, Love knew that he would have to match his opponents brick for brick.

For the umpteenth time Love asked Howard Horne how things were coming on Block 68. Horne was still optimistic that the land could be assembled, but Love was growing impatient. It had been eight years since the purchase of the Montgomery Ward property, and the bank still owned only about two thirds of the block. How much longer would it be? Horne, knowing well the vagaries of downtown real estate, couldn’t say.

It was about this time that A. J. Layden, president of Allright Auto Parks of Houston and a longtime customer of the bank, came to Love with another proposition. Allright owned all of Block 67, which was one block west of the proposed building site, directly south of the Chronicle Building. The block was now used as a parking lot, so building on it could start almost immediately. But the price would be $90 a square foot, or $5.6 million.

Love thought long and hard about the offer, even though the price was $20 to $30 higher per square foot than what he considered market value. He talked again to Horne, who still seemed confident. The thought of building away from Main Street didn’t hold much appeal for the bank that had helped build Main Street. And besides, thought Love, there is no reason to believe that the shift of development westward will last forever. He still wanted Block 68. He allowed the bank’s option on Block 67 to lapse.

Mr. Horne Perplexed

R. E. “Buddy” Clemons knows from experience that big corporations and old Houston families don’t always mix. Only last year Clemons tried to purchase a one-story building at Main and Clay for a New York investment firm. When he looked at the plat, he almost screamed—42 joint owners, all of them descendants of Captain James Baker. Then, in a display of diplomacy and patience the State Department would have envied, Clemons proceeded to get in touch with all 42 and, after a lengthy family meeting, consummated the deal.

Clemons is one of Howard Horne’s best negotiators, the man Horne calls when someone else has struck out. Sometimes all it takes is a new approach, or simply a new face, to break down the defenses of an owner who has held out for years. So in 1970, before Cleve Brown had agreed to sell his property on Texas Avenue, Horne handed the Block 68 file over to Clemons.

There were good reasons for choosing Clemons. In the mid-fifties, as a young assistant at the Paul E. Wise Company, Clemons had helped put together the block for First City National’s new building. That deal had almost disintegrated at the very last minute when a dress-shop owner who held a three-year lease in a building First City had purchased decided that the rest of his lease was worth about $1 million to the bank and announced that he would continue to sell dresses until the ransom was paid. Judge James Elkins, president of the bank, responded by ordering the design of the new tower redrawn so as to avoid the only remaining building, and the next week he erected a DANGER—MEN WORKING sign in a second-floor window above the dress shop. The owner held out for another three months, then agreed to accept $35,000 instead of $1 million for his lease. But the First City Building went up on the other side of the block anyway.

When Clemons first looked at the Block 68 file there were ten owners left, all facing Main Street, with building frontages ranging from fifty feet (Alaskan Furs and Pay-Less Drugstore) to ten feet (the Tie Rack). Except for a twelve-foot lot owned by G. S. Cohen, the aging cofounder of Foley Brothers Department Stores, Clemons didn’t recognize any of the owners’ names. He found out who they were soon enough.

The first target was a building near Texas and Main owned by Marion Settegast, whose ancestors had passed the land down to the third generation. To anyone but Settegast, the property might not have seemed too valuable, occupied as it was by a fur company down on its luck and a discount drugstore. But Settegast remembered a day in the forties when Alaskan Furs, then a fashionable carriage-trade shop, had offered $500,000—or $100 a square foot—for the building. If it was worth that much then, think what it must be worth today. It was not worth that much today, insisted Clemons as he tried to explain that land, contrary to the popular myth, can depreciate in value even in Texas. But the Settegast family was adamant. If they hadn’t sold it for $100 per square foot in the forties, why should they even consider a $70 offer in the eighties?

It was old family land, it had once been extremely valuable and might be again, the family was wealthy enough not to need the extra income—this was the pattern, over and over again, that Clemons had to deal with for the Main Street frontages. Jesse Jones had done his work well. And now there was another liability to overcome. After six years of knocking on doors, persuading, and cajoling, the secret was bound to get out. Texas Commerce Bank was trying to buy Block 68, and everyone in town knew it. That was the hardest thing to deal with—the idea, as Clemons put it, “that a bank is a bottomless pit of money.’’

In the end, Horne and Clemons were forced to appeal to civic pride. This was a major building project, a credit to the city, a boon to the economy. It’s the wave of the future, they said. Retailing in downtown Houston is all but dead. You can delay, resist, and postpone, but you can never block progress. And much more in the same vein.

“The thing you have to remember,” said Horne, “is that not needing money—and these were all wealthy people—makes land more expensive. Even that has a value.”

The Settegasts’ resistance crumbled when the price rose to $84 a square foot—almost twice the price of the Montgomery Ward lot sold in 1967—and each of Clemons’s successive victories became more expensive. Clemons had virtual carte blanche to make modest price increases, since the size of the lots diminished as he got nearer to completing the block and the target price was an average of $100 per square foot for the entire block, which meant that the last holdouts could conceivably get up to $300 or $400.

After the Settegast deal Clemons moved on to the building next door, a 25-foot frontage occupied by National Shirt Shops but owned by Mrs. Mae Carter, the eighty-year-old widow of a wealthy West Texas rancher. Mrs. Carter hadn’t been to Houston in years, but she was not interested in giving up the property. The rent amounted to $30,000 a year, and she relied on that steady income as though it were a pension. She didn’t care about the price; she did care about having a monthly check. Clemons saw that he was in for a long battle, so for the first time he broke the pattern, put aside the Carter property, and decided to work the rest of the lots simultaneously. If he could get hold of a few more buildings, the rest might see that the time had come to sell.

There were eight lots between the corner of Main and Capitol and the National Shirt Shops building. Some of them were easy. The seventh (counting from the corner) was still owned by a corporation Jesse Jones had set up when he gerrymandered the block, so it was acquired right away. The sixth was a building housing two shoe stores that was owned by J. J. Brashear, a retired investor who lived in Greenwich, Connecticut. After a year or so of quiet persuasion, Brashear was happy to take $135 a square foot. The fifth and fourth, housing a Flagg Brothers and the Tie Rack, were owned by a Mr. Gutierrez of Mexico City, who was amenable to a deal and agreed to a similar price without ever hearing that the bank was the buyer. And the second lot, home of a store called Cut Rate Linens and owned by a Mr. Saxton of Austin, was acquired through a 99-year lease so that Saxton could avoid taxes on capital gains.

After two years of more or less steady progress, Clemons had reduced the problem to four buildings with recalcitrant owners. They were the corner lot, occupied by Wexler Jewelers and owned by a Houston attorney, Bill Ladin; the third lot, owned by Levit’s Jewelers; the eighth, occupied by the Felix Mexican Restaurant and owned by G. S. Cohen, cofounder of Foley’s; and the ninth, Mrs. Mae Carter’s building.

Clemons dealt with Mrs. Carter first. Her original reluctance to sacrifice the property’s monthly income began to fade when the price rose into the $100-per-square-foot range. But another problem persisted: National Shirt Shops had a fifteen-year lease on the building, and that store was currently the chain’s second-best money-maker in the nation. So Clemons searched high and low for other buildings available on Main Street that would be equally attractive to National Shirt. He found one less than two blocks away, in a theater that had recently closed, and negotiated a twenty-year lease with the owner. Mrs. Carter finally agreed to the sale, and the bank paid to move National Shirt Shops to its new home north of Texas Avenue.

The other three would not be so easy. G. S. Cohen was a reclusive man whose office was still on the ninth floor of Foley’s downtown store, whose door was assiduously guarded by a strong-willed secretary named Mrs. Doyle, and whose standard answer to real estate brokers was “I have no price.” After a first offer of $65 a square foot for the Felix restaurant, Clemons had steadily raised it over a year to $80 with no sign of life from Cohen or interest from Mrs. Doyle. He later learned that Mrs. Felix Tijerina, owner of the restaurant, was a friend of the Cohen family, and they had promised to protect her business as long as she wanted to stay there.

Clemons wondered how Cohen had acquired the lot in the first place, since its twelve-foot frontage made it suitable for only the tiniest of businesses. The answer, according to sources who remember the deal, was that Jesse Jones himself had sold it to Cohen in the late thirties when Montgomery Ward moved onto the block. Cohen had feared that Montgomery Ward would be able to buy that lot and use it for a Main Street entrance to the store at Capitol and Travis. So, for the same reasons that Jones had bought his lot, Cohen bought a lot from Jones, to block any expansion of his rival. It worked. Montgomery Ward never did get the opening to Main Street.

Clemons was pondering this and other things and wondering how persistent he should be with Mrs. Doyle when a startling turn of affairs appeared to end the deadlock: in December 1971 Cohen died. Even before his will had been submitted to probate court, Clemons had asked an attorney at Vinson & Elkins to approach Mrs. Cohen. Clemons’s temporary hopes were dashed by more bad news: Mrs. Cohen didn’t want to discuss it either. And the bad news was followed by worse: the Cohen estate, which included the Felix building, had been assigned to the trust department of First City National Bank. “You can imagine the street talk that developed at that point,” said Clemons. “‘First City has Texas Commerce by the you-know-what.’ That sort of thing.”

First City did indeed have Texas Commerce by the you-know-what, and Clemons decided not to press his luck. For the next two years he turned his attention to the other holdouts—Bill Ladin, on the corner, and the Levit brothers, who were third from the corner. Ladin was not averse to selling the building, but he wanted some peculiar terms: $200 a square foot and a “grandfather” clause in which Texas Commerce agreed to pay him the top price on the block if any of the parcels brought more than $200. Horne and Clemons didn’t particularly like the clause—since it precluded them from offering the moon to the last holdout to get the block completed—but they decided to go along anyway, and the deal was closed.

The Levit brothers were another matter. To this day Clemons doesn’t know exactly what they wanted, and he charges that they changed the terms of a prospective deal several times in midcourse. At one point Clemons agreed to get them a space in Gulfgate Mall, until he discovered that Gordon’s Jewelers had an exclusive lease there, and on another occasion he located a building for sale in the Post Oak area. The Levits decided they didn’t want the building. They were happy where they were. Price was discussed in only the vaguest of terms, and Horne grew so exasperated that he quit calling on them at all. Finally Clemons, too, gave up and told Ben Love that the bank would have to carry on its own negotiations with the Levits. The Horne Company had done all it could.

Meanwhile, Clemons was making his first tentative approaches to the trust department of First City National Bank, which now had control of the Cohen property. His initial offer, delivered to the trust officer, was a price of $135 per square foot, the same deal Brashear had received but $55 more than Clemons had offered to Cohen while he was alive. The trust officer didn’t seem too interested, so a year after that Clemons came up with another plan. If First City, the Levit brothers, and Bill Ladin would all accept $188 a square foot (this was before the final Ladin deal), then Texas Commerce would pay it. It was a full $50 above the highest price yet paid on the block, but none of the three even bothered to answer Clemons’s letter. The First City trust officer did call to say he was having the property appraised.

The appraisal must have taken some time, because it was not until a year later that the bank officer called Clemons with an offer. The land, he said, was worth $331 a square foot, and he wouldn’t take less. Clemons had a word for this offer, which can’t be repeated here. Instead of answering First City, he called Ben Love. Love appealed directly to Mrs. Cohen herself, and after a conversation between Love and Judge Elkins of First City, the $331 demand suddenly disappeared. The final sale price was “in the two-hundred-dollar range,” according to Clemons.

That made Levit’s Jewelers, in a building 21 feet wide by 100 feet long, the only structure left between Ben Love and his new building. Howard Horne talked to the Levits and came away totally discouraged. Clemons talked to all four of the brothers and found them impossible to deal with. Finally, the senior officers at the bank and at the Horne Company began discussing alternate strategies. The most imaginative was a plan to go ahead with a major office tower that would extend to the northeast, northwest, and southwest corners of the block, with the southeast corner (an area large enough to include Levit’s) left as open space. The bank would then donate the first, second, and fourth lots on Main Street to the City of Houston for park space, leaving Levit’s standing awkwardly in the middle of a city park. The officers couldn’t say what would happen next, but perhaps the city would choose to exercise its powers of eminent domain. The proposal was made only half in jest, an indication of how bitter feelings had become.

Mr. Love Plays Hamlet

By 1977 Ben Love had decided he couldn’t wait any longer. It seemed that all his rivals had major buildings in the works, including Bank of the Southwest, First International Bank, and First City National (a second tower), and there were rumors that Allied Bank would be moving out of the Esperson Building. The Levit brothers were still holding out, the building boom in the west end of downtown showed no signs of slowing down, and, well, that block in front of the Chronicle Building was looking better all the time. Love put his staff to work finding out whether Allright Auto Parks was still interested in selling, and fortunately they were. The price had gone up—it was now an even $100 per square foot—but given the headaches of putting together Block 68, Block 67 looked like a bargain.

Now Love was faced with an excruciating dilemma. After ten years of constant work on Block 68, was he really willing to let all that effort go down the drain and build on a block that he could have acquired any time he had wanted it? It was Love, after all, who had passed up a chance to buy Block 67 a full two years earlier, and the block hadn’t moved one inch closer to Main Street. By this time the bank had spent $5 million on land purchases, and 95 per cent of Block 68 already belonged to Texas Commerce. Still, if anyone could hold out forever, it was the Levit brothers. Perhaps Jesse Jones had known that. Nobody will ever be able to put that block together again. But time was running out now; even some of the vice presidents were cramped in the overtaxed Gulf Building.

Opinions differ as to why Love changed his mind. Some say it was the Levit brothers who destroyed Love’s dream of a new bank on Main Street. Others say that at long last the bank recognized the new economic realities of a downtown that had shifted to the west. For whatever reason, Love made his move. Hang the Levits. He would build on Block 67.

Mr. Love Hires Mr. Hines

Thirty years ago, putting up a major office building in downtown Houston was, relatively speaking, a simple matter. Jesse Jones’s habit had been to sketch the general design of the building on scratch paper, then call the architects in to build wooden models and draw up the actual blueprints. (Architects, to Jones, were little more than day laborers.) Then Jones went to a friendly banker, showed him the models, submitted a rough cost projection, and walked out with the money necessary to finance the construction. Leasing began when the structure was completed, and the building was not named until the primary tenant was in place. “Any dumb person can put up a building,” Jones was fond of saying.

In 1977, any dumb person with at least $50 million could put up a skyscraper in Houston, but any smart person wouldn’t try it. The market for Houston office space was more competitive than ever, and the subtleties of architecture, interior design, and financing became ever more complex with each passing year. Ben Love knew that because of the price he had paid for Blocks 67 and 68, he would need a building of at least forty stories to get his investment back within a reasonable period. He also knew he would need outside advice.

For a grandiose project like the one Love had in mind, there were really only two men in Houston he could turn to—Kenneth Schnitzer, the developer of Greenway Plaza and Allen Center, or Gerald Hines, who had been putting up the classiest landmarks in downtown Houston ever since his daring One Shell Plaza was announced in 1969. Both men are known in the trade as “investment builders,” a catch-all term that means they arrange financing, hire architects, supervise construction, lease office space, and finally undertake management of a building erected for the benefit of someone else. Investment builders have no particular technical skills—they hire engineers, architects, and designers from other companies—but they do have an intricate knowledge of everyone else’s business. Their chief assets are business judgment and taste.

Texas Commerce actually considered three investment builders—Hines, Schnitzer, and Galbreath-Ruffin of Columbus, Ohio—but from the beginning there was little doubt that Hines would get the job. Gerald Hines Interests had been an important Texas Commerce customer ever since the early sixties, when Hines occupied himself primarily with small warehouses in Houston’s industrial districts, and the bank had financed such impressive Hines projects as the Galleria, Pillsbury Center in Minneapolis, Three First National Plaza in Chicago, and Seafirst Fifth Avenue Plaza in Seattle. Moreover, Hines and Love were personal friends.

Gerald Hines is a taciturn, bespectacled man whose cautious way of dealing with the outside world gives little indication of the size of his building empire (which stretches from Cairo, where a Galleria-style project is in the works, to Peking, where Hines is developing the new China Foreign Trade Center) or the intensity of his ambition. Hines is not unaccustomed to working twelve-hour days, even though he has 690 employees at his beck and call, and his reputation among architects as “the Medici of the West” has not softened in the least his reluctance to discuss any of his financial dealings with outsiders.

The one thing Hines will talk about is his buildings. Described by his friends as a frustrated architect at heart, Hines has established a remarkable rapport with the premier building designers of the United States, resulting in a marriage of innovative design and cost-effective building once considered all but impossible. “Hines is enough of a businessman to know that he has got to push his architect in certain directions,” says Philip Johnson, the New York architect, “but he is also enough of a patron to know where to stop.”

Like Jesse Jones in the twenties, Gerald Hines today is Houston’s biggest landlord. More important, he pioneered the sleek look of western downtown Houston, first with One Shell Plaza, then with the prizewinning Pennzoil Place, and more recently with the almost complete First International Plaza. Each building was considered a risk at the time—because of daring design and the bold moves away from the historic center of town—but all have a leasing rate of better than 99 per cent and continue to be consistent moneymakers. It was Gerald Hines, in fact, who helped make the Texas Commerce project possible, when he completed Pennzoil Place, Houston’s largest office complex, in 1975. Not only was it the first Philip Johnson office building in Houston, but it was constructed on an isolated block just one street south of Texas Avenue. By moving back toward the north, Hines helped avert the slum scenario that had so worried Texas Commerce officers for more than ten years.

When Ben Love told Hines of his plans for the new bank building, Love was still trying to make up his mind whether to build on Block 67 or Block 68. To Hines, there was no question. Block 67, the Allright parking lot, was the superior block, not least because his own Pennzoil Place touched corners with it, so that the new building could easily be attached to Houston’s underground tunnel system. “There were other considerations, too,” Hines explained later. “Nobody likes to be in a building that overlooks a parking lot. Nobody likes to be isolated. The kind of people who locate in downtown Houston are there for one reason—it’s easier to do business when their lawyers, accountants, and bankers are close at hand. And nobody wants to walk three blocks outside to his banker’s office on a hot summer day when he can go through the tunnel system and be there within five minutes.”

But Hines doesn’t do business overnight. Friends are friends, but it still required ten months of almost continuous meetings between Hines people and Texas Commerce people to hammer out the particulars of the joint venture. One thing Hines wanted was a guarantee that the bank would occupy at least 20 per cent of the building, an important detail in the minds of lenders. One thing Love wanted was a guarantee that the building would be at least 56 stories high. Why? Because the new First International Plaza was planned for 55.

Finally, in the very early stages of planning, the bank had to make some decision about the monumental old Gulf Building lobby, known to its customers for years as the House That Jesse Built. If people complained when Jones’s portrait was removed from the wall, what might they do if the old lobby were mothballed forever? The bank decided it would rather not find out. The primary consumer banking operation would remain in the Gulf Building, and the new tower would be used for additional office space only.

Messrs. Love and Hines Attend the Theater

The seven architects were given a simple mandate. They had one month and $15,000 each to design the most beautiful building in Houston. The building would have a significant “skyline profile,” it would fit comfortably with other nearby landmarks like Jones Hall, Pennzoil Place, and the Chronicle Building, it would be energy-efficient, and it would stand at least 56 stories tall.

The contest idea had been Gerald Hines’s, but Love took to it with alacrity. In strict terms this was not an architectural competition, since there would be no panel of experts to do the judging, but it was the best means Hines could think of to ensure the kind of dramatic building that Love had in mind. On the appointed day in December 1977, two dozen people crowded into the fourth-floor theater of the Gulf Building to hear the contestants make their free-form presentations.

First into the theater was Minoru Yamasaki, the 67-year-old Detroit architect best known for his controversial World Trade Center in New York. Following him were Romaldo Giurgola of the Philadelphia firm Mitchell/Giurgola, known for its restrained, classical public buildings in the metropolises of the Eastern seaboard; Hermon Lloyd, whose firm, Lloyd Jones Brewer & Associates, had designed such Houston landmarks as the Astrodome, Rice Stadium, Allen Center, and Greenway Plaza; J. V. Neuhaus III, president of 3D/International, a Houston firm with a worldwide reputation for its work in Saudi Arabia on the royal palace, the headquarters for the national guard, and a $1 billion New Town, and closer to home for its NASA complex in Clear Lake City and many of the landmark buildings at the University of Texas at Austin and Rice University; Cesar Pelli, dean of the Yale University school of architecture, whose notable projects include the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, the U.S. embassy in Tokyo, and an expansion of the Museum of Modern Art in New York; I. M. Pei, the celebrated New York architect whose work in the downtowns of the major cities, including the new Dallas City Hall, had made him the latest darling of the architectural press; and “Tiny” Lawrence of the CRS Group, which also has projects in Saudi Arabia as well as 45 other countries, and such stunning prizewinners as One Houston Center and the acclaimed Merchants Plaza in Indianapolis.

It was a memorable show, but everyone there remembered three performances in particular as superior. The first was that of Yamasaki, a quick-witted, talkative man who had brought not one but several building models, which he lifted out of a box and shuffled like the components of a giant toy city. Explaining how each concept had displaced the previous one in his own mind, he then went over each detail of the monumental edifice of marble and travertine that he had chosen as the ideal shape for the bank. “Tiny” Lawrence was equally impressive when he unveiled a model of twin glass towers, then recreated the conception and design of the buildings by drawing freehand on a set of flip charts he had brought with him.

But the man who eventually carried the day was a slow, distinctive speaker with a rather timid manner who talked almost as much about Jesse Jones and Jones Hall as he did about his own building. I. M. Pei’s tower spoke for itself. Even the model was nearly as tall as a grown man, reaching skyward for what Pei represented as seventy or eighty stories. Pei had walked every inch of the six blocks surrounding Blocks 67 and 68, and he spoke of Jones Hall as a civic monument in almost reverential tones. His five-sided granite tower, he said, would be placed on the extreme northeast corner of Block 67, leaving a full acre of open space for a public plaza directly opposite Jones Hall. The building would also face Pennzoil Place, at a 45-degree angle to the street grid, thereby reflecting light in a different direction from any of the other skyscrapers and providing a line-of-sight link between the Gulf Building, the monument of Jones’s life, and Jones Hall, the building erected after his death. The enormous space created by the one-acre plaza would not only avoid the canyon effect of adjacent skyscrapers but would also serve as a natural gathering place for downtown pedestrians. To top it all off, Pei pointed out that, like Jones, he had designed a lobby of magnificent proportions, a full 65 feet from floor to ceiling, which—voilà!—is the exact height of the lobby in Jones Hall.

The presentation, as Ben Love remembered it later, was electrifying. Pei’s concept had everything—a sense of history, a sensitivity to the shortcomings of downtown Houston (specifically, the lack of open space), a reverence for what had already been built, and, not least, a grand scale. “Another reason for the huge lobby,” Pei would say later, “is that this is not the kind of building you want to crawl into.”

It was dark outside by the time the executives left the building that day—the seven presentations had required a full twelve hours—but Love and Hines were both convinced that their $105,000 had been well spent.

Mr. Boyd Comes Aboard

The lengthy negotiations between Gerald Hines Interests and Texas Commerce Bancshares finally resulted in a stack of legal documents several inches high. The essence of the deal, however, was simplicity itself. Texas Commerce would own the land and the building, but Hines would hold an exclusive 65-year lease on both. The bank would receive a minority share (amount undisclosed) of the building’s long-term profits, and on all major decisions—especially those involving the building’s tenants—the bank would be consulted. It was a classic Hines agreement. But despite the fast pace and speculative nature of high-stakes building development, Hines is a conservative’s conservative. Before he even begins to seek out financing he prefers to have at least one, and preferably two, tenants already booked into the building. Texas Commerce had agreed to take a minimum of fifteen floors in what was now projected as a tower of at least seventy stories. Still, Hines wanted more insurance.

It so happened that Howard Boyd, a member of the Texas Commerce board of directors, was looking for a new corporate home at that very moment. Boyd was chairman and chief executive officer of the El Paso Company, a diversified energy corporation whose eight thousand employees were presently squeezed into cramped quarters in the American General Building on Allen Parkway. Boyd’s first concern was finding new space, but he was not unaware of the public relations value of locating in a Gerald Hines building. Pennzoil Place had been worth reams of publicity to its chief tenant after the architectural critics of the world pronounced it a Philip Johnson classic. Now I. M. Pei was designing a building just a block away, and Ben Love’s enthusiasm about the design was contagious. Boyd called Love to talk over the possibilities, and during the first few months of 1978 El Paso, the Hines Interests, and Texas Commerce tried to come to terms.

Each of the three companies wanted something different. Hines wanted a commitment from Boyd that El Paso would occupy most of the building above the sixtieth-floor “sky lobby,” at a price of about $16 a square foot. Love wanted Boyd’s assurance that the lease would be long-term, and Boyd was interested in what is known in the industry as “identification.” There are really two sorts of identification—building ID and site ID—and they amount to the same thing: one of the tenants’ names becomes part of the address. Until now, it had been assumed that the building would be called Texas Commerce Tower, but Boyd’s interest in identification led to some peculiar problems. The bank, after all, had instigated the project and by all rights should be able to name the building. On the other hand, El Paso was agreeing to take more space than Texas Commerce. Alternatives were tested. Perhaps the whole complex, both tower and open space, could be called El Paso Place, or El Paso Center. (Somehow El Paso Plaza didn’t have the right ring. It also sounded like it belonged in El Paso.) Eventually a compromise was reached. Since the bank still intended to use the Gulf Building as its consumer banking center, the name of the tower was not that important. Final verdict: the building would be the El Paso Tower in Texas Commerce Plaza.

Once the El Paso Company had agreed to take the space—which in the end amounted to twenty floors in the upper part of the building—Hines began his search for financing in earnest. By now the value of the project had increased to $140 million, due to the addition of a twenty-story parking garage, health club, and data processing center for the bank on Block 68 and a drive-in banking facility several blocks away. And that figure was high enough that Hines wanted to hedge his bets. First he looked for a partner to share the risk.

It took Hines less than a month to find one, in the form of a European investment group called Netherlands Antilles Corporation. In exchange for equity in the project, Netherlands Antilles was guaranteed a substantial percentage—some say up to 50 per cent—of the building’s profits. The importance of that agreement was that it would lower the break-even level in the event the building space was not 100 per cent leased. To avoid paying high interest rates to lenders on a building that didn’t generate enough money to retire its debt, Hines got the investment group to agree that it would receive no income until the building showed a profit. Most developers would try anything before giving up such a high percentage of their profits to outsiders, but Hines’s continuing growth is based on this sort of ultraconservative investment policy.

The next two months were spent lining up his long-term lenders; because of the project’s size he needed two of them—New York Life Insurance Company and the New York State Employees Retirement System. Only after that deal was signed did Hines begin to look after the nitty-gritty details of money for the actual construction. That money came from fourteen American banks scattered from coast to coast (to allow for regional downturns in the economy), and the consortium included Texas Commerce Bank of Houston.

Four Gentlemen Stage a Party

As of July 1978, the all-but-final plans for construction of El Paso Tower in Texas Commerce Plaza, a project in the works for eleven years now, were still little more than a rumor within the investment and building circles of downtown Houston. One of the worst things that can happen to a new office building is for its newness to wear off before it is ready for leasing, and for that reason, as well as the embarrassment that could accompany any breakdown in financing or tenant negotiations, such plans are best kept secret from the public.

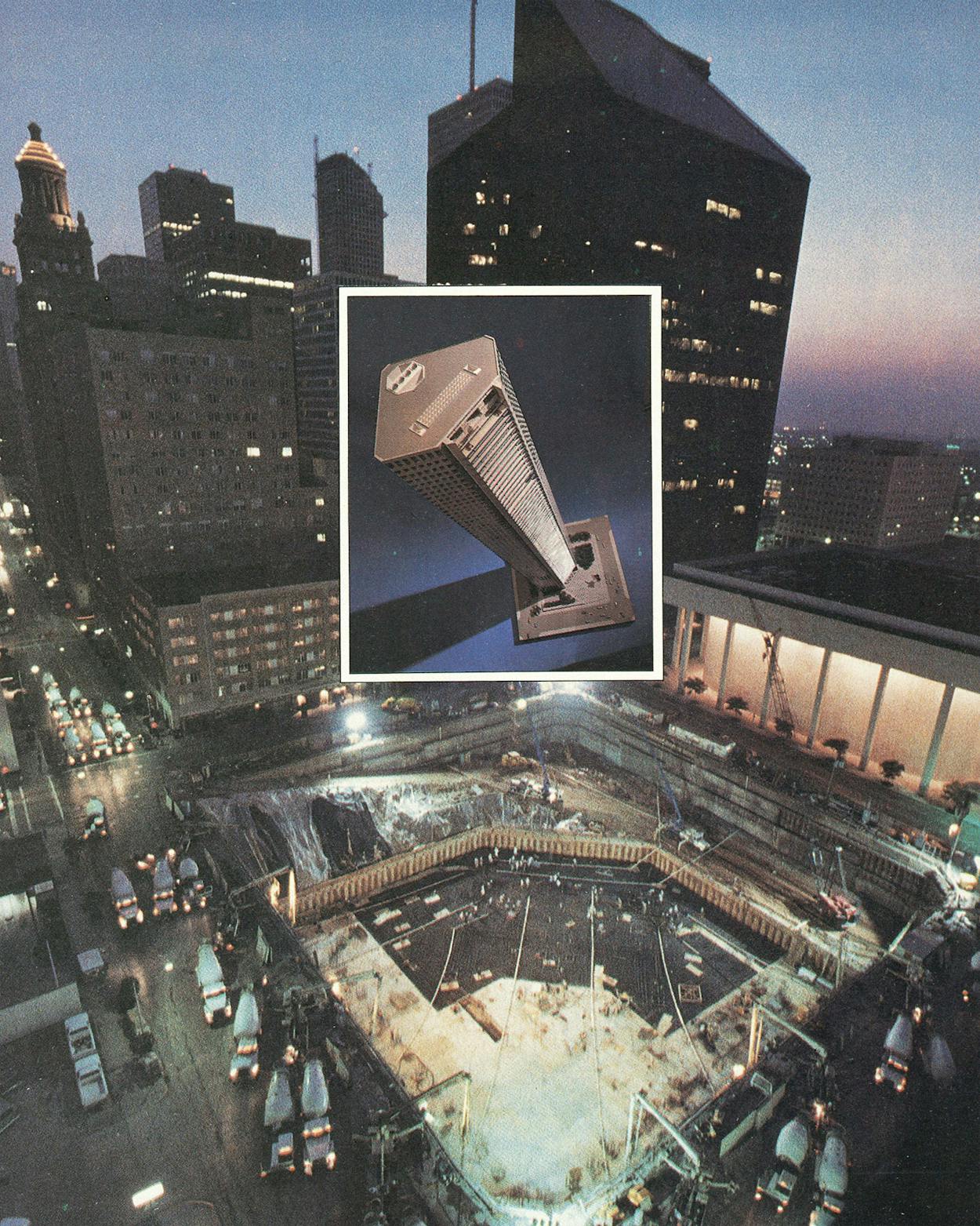

One of the next worst things that can happen to a new office building is for it to open for business and not be noticed at all. That never happens to Gerald Hines, who proceeded to announce this building with the panache of P. T. Barnum. Now that Hines had two large tenants and all of his money, it was time to spread the word. In early July 1978 more than a thousand of Houston’s most powerful and influential citizens—bankers, architects, engineers, reporters, potential tenants, city councilmen, the mayor—received plastic invitations to a ceremony at Jones Hall featuring speeches by Gerald Hines, Ben Love, I. M. Pei, and Howard Boyd. To make it even more memorable, Hines’s marketing staff included with each invitation an eight-inch scale model of the new tower and plaza, fastened onto a square block of the same granite to be used in the building’s construction. The impressive phallic paperweights cost $10 each—for a total of $10,000 in souvenirs—but the actual architectural model of the building ran even more. It cost $50,000 and was itself two stories high.

Gerald Hines is known as a ruthless cost cutter on the nonessentials of development, but when it comes to selling the building to prospective tenants, his budget for song and dance is without parallel. Besides throwing the opening-announcement gala, Hines constructed a spacious model office on the first floor of Pennzoil Place that displays details of the interiors as they will look in the new Pei building, including carpet, doors, and floor plans. He also commissioned a twelve-minute audiovisual show that incorporates a brief history of Houston, the legend of Jesse Jones, a cameo appearance by I. M. Pei, and dramatic photographs, presumably taken from a helicopter, that illustrate exactly what the building’s view will be. He has a complete scale model of downtown Houston as big as two king-size beds, with the new tower rising spectacularly out of its northern end, more than twice the height of Pennzoil Place. And his hefty silver-embossed media kit contains reams of maps showing such important details as the location of all private clubs within walking distance of the tower, the underground tunnel network, traffic patterns on surrounding streets, and the exact number of parking spaces within a one-, two-, or three-block radius of the building.

All of this is done in the name of what Hines calls “leasing momentum.” The operative idea is that the quicker the building is filled up, the more desirable it will appear to be and the less the chance of its becoming a white elephant. Often the best thing that can happen to a Hines building is for the tenants of other Hines buildings to transfer to the new one. Structures like Pennzoil Place, One Shell Plaza, and Two Shell Plaza have built up a reputation within the business community that allows them to fill empty space as quickly as it is vacated. In moving friendly tenants into the new tower, Hines will still have virtually no lapse in income at his other sites.

By any reasonable measure, the massive promotional effort worked. As of March 1, a full year before the new tower will open for business, Hines had already leased 82 per cent of its space.

Mr. Boyd Goes Ashore

In July 1979, nine months after ground had been broken for El Paso Tower, Ben Love was still troubled. From his third-floor suite in the Gulf Building he could see the vast hole in the ground where Block 67 used to be, and one night he had watched with everyone else as a battalion of a thousand cement trucks lined up in double file along Travis Street to pour the largest concrete foundation Gerald Hines had ever needed. But now there were other problems, some minor, some major. First the Federal Aviation Administration had told Hines that an 80-story building would not be allowed in Houston because of the low ceiling of 2000 feet used by the area’s air traffic. Since the FAA would sanction no structure higher than 1049 feet, the building plan had been revised to a mere 75 floors. Then the building engineers had discovered that the foundation was so massive that it would need to be supported with beams running under Travis Street and Texas Avenue. Since the bank had no permit for invading city rights-of-way, that problem required a visit with Major Jim McConn. Fortunately, McConn’s reply was quick and decisive. “No problem,” he told Love. “I think the building is a credit to the city.”

But now there were other irritations. The Levit brothers apparently intended to sell jewelry at their Main Street address despite anything the bank could offer them. Their continued presence no longer threatened the tower itself, but it did disrupt plans for the parking garage and data processing center. At first that building had been almost an afterthought, an attempt to assuage the bank employees’ grumblings about the lack of adequate parking space. But since then even I. M. Pei had become excited about it, and he intended to adorn the garage with a granite facade identical to that of the tower—“a mother to the father,” he called it.

Even more important, Howard Boyd was retiring at the El Paso Company, and the management shake-up there had produced a new frame of mind. For one thing, the company was no longer so sure that it wanted a high-profile identification with a downtown skyscraper. For another, a major tenant in the American General Building had just moved out, leaving more than enough space for El Paso without the trauma of a substantial corporate move. Very politely, El Paso had asked to be released from its contract. Legally, it had an obligation to move into the building and remain there for twenty years, but the last thing Hines wanted was a dissatisfied major tenant, especially when that tenant’s name was on the building.

The rumors on the street were that the El Paso Company and Gerald Hines had had a falling-out over the terms of the contract, but Hines tells it differently. “When they came to us and said they were reconsidering,” said Hines, “I finally decided that it was better for us if they pulled out anyway. The reason is that they had signed a long-term lease in the days of what now seem like very low interest rates. Those rates had gone so high by the summer of 1979 that I could buy back El Paso’s lease, resell the space to another tenant, and realize a greater profit.”

Hines is not saying exactly what that profit was, but space in the upper floors of the tower now leases for about $18 a square foot, in the building as a whole for an average of $14. Surprisingly, that’s only about 50 cents more than comparable space in other downtown skyscrapers. And Hines even had a tenant in mind—United Energy Resources, Inc., a utility bigger than most Fortune 500 firms that was rapidly outgrowing its offices in Pennzoil Place. United Energy was also interested in “identification,” and so the process of negotiation began anew.

Somehow the name United Energy Resources Tower didn’t strike anyone’s fancy. Neither, for that matter, did United Energy Tower. And given the history of the building to date, Ben Love wasn’t too anxious to put another outsider’s name on the project. When the dealing was over, the building was called what it had been called in the first place—Texas Commerce Tower—but it had a new address: United Energy Plaza.

Mr. Love Fulfilled

Meanwhile, I. M. Pei’s fertile imagination had recently become distracted by yet another Texas Commerce building. When Love first told Pei that the bank needed a drive-in facility, Pei’s response was “What is that?” It seems that the guru of urban architecture had never seen a drive-in bank. Love patiently explained that all Texas banks have one building for pedestrians and another for motorists, and Pei’s eyes flashed. Refusing the opportunity to look at other drive-in banks, Pei designed his own—an innovative building with circular lanes that concentrate all the automotive customers near the center of the block and feed them out on all four surrounding streets. “This will be the child building,” he said, “to go with our father and mother.”

The next order of business was a major sculpture, to be selected by Pei, Love, and Hines and placed in a strategic location in United Energy Plaza. Outdoor sculptures are de rigueur for anyone who aspires to own a great building these days, but part of the impact derives from the dramatic unveiling. Not surprisingly, the trio of patrons will not reveal anything about their current negotiations with the world’s leading sculptors, but in a moment of weakness one of them did mention the name of Joan Miró. Presumably his soft, feminine designs would contrast with the vertical thrust of the tower.

Only one hitch remained—the Levit brothers. This time the job of reasoning with them was assigned to Marc Shapiro, a brilliant executive just thirty years old who had risen meteorically to become the bank’s chief financial officer. And in December 1979, ten years almost to the day since Buddy Clemons had made his first visit to the jewelry store, Shapiro made peace with the Levits. The twenty-story “mother” building—which already included a parking garage, a data processing center, and a health club—would now have a retail level along Main Street. You can guess whose jewelry store was assured of spacious accommodations at the corner of Main and Capitol.

Epilogue

In January the financial statements for the 15 largest regional bank holding companies in America were released by the Federal Reserve. Texas Commerce Bancshares was ranked first in return on assets (1 per cent), third in return on equity (17.8 per cent), fourth in equity-to-assets ratio (5.6), and third in annual earnings increase (28 per cent). Only one other Houston company even came close to that performance—First City Bancorporation. And its new building is only 49 stories high.