This story originally appeared in the December 2017 issue with the headline “Two-Billion-Dollar Buyer.”

Tilman Fertitta first learned that the Houston Rockets were for sale, appropriately enough, from the team’s public address announcer. It was the afternoon of July 17, and Fertitta, the billionaire owner and CEO of the Landry’s restaurant group, was in New York on business when he received a text message from Matt Thomas, the man whose solemn duty it is to intone, before each home game at the Toyota Center, the requisite liturgy: “Red Nation! It’s time to run as one for your Houston Rockets!”

Fertitta and his family had been season ticket holders for decades, going back to when the Rockets played at the old Compaq Center, formerly the Summit. Since the Toyota Center opened, in 2003, Fertitta had sat courtside, right at the half-court line. Over the years, he’d become friends with many longtime Rockets employees, including Thomas.

On that July afternoon, Thomas texted Fertitta. “He said, ‘If you buy the team, please keep me,’ ” Fertitta recalled. “I was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ ”

Thomas, it turned out, was at a press conference in Houston that had been hastily arranged by Rockets CEO Tad Brown to announce that Leslie Alexander, the Wall Street bond trader who had owned the Rockets for nearly a quarter century, was putting the team up for sale. Brown himself had learned of Alexander’s decision only earlier that morning, when he received a phone call from the 74-year-old billionaire. “He told me that he had been thinking about it, that he wanted to make a change in his life, and that he was going to sell the team,” Brown said. “I never thought that Leslie would ever sell. But once he made up his mind, we were ready to go, and we started the process that day.”

Fertitta had known Alexander for decades and was under the impression that he’d planned to eventually leave the team to his daughter. The two first met in 1993, the last time the team was on the market, when they were rivals vying for ownership. Fertitta, who had made a small fortune from Landry’s, already owned 3 percent of the Rockets and made an $81 million offer to buy the other 97 percent—only to fall $4 million short of Alexander’s winning bid. Fertitta was forced to literally watch from the sidelines as the Rockets, led by Hakeem Olajuwon, went on to win back-to-back championships in 1994 and 1995.

“I didn’t think the Rockets were ever going to sell,” Fertitta told me in September. We were sitting across from each other in the expansive cabin of his helicopter, a black Airbus H155, en route from Landry’s corporate headquarters in the Houston Galleria area to Austin, where the sixty-year-old businessman would be filming an episode of his CNBC reality show, Billion Dollar Buyer. “I kind of saw it as my last opportunity to buy a sports team in Houston during my lifetime. A lot of people don’t mind buying sports teams in other cities, but I really didn’t have a desire to do that.”

Fertitta’s devotion to the Rockets runs deep. He’s been a near-obsessive fan of the team since it moved to Houston from San Diego, in 1971, when he was in junior high in Galveston. He can readily reel off stats and stories about the Rockets greats who came and went over the subsequent decades: Elvin Hayes, Calvin Murphy, Rudy Tomjanovich, Moses Malone, Ralph Sampson, Tracy McGrady.

In 1983, as a burgeoning entrepreneur in Houston, Fertitta used some of his new wealth to buy that 3 percent stake in the team. Later in the decade, he and his future wife, Paige Farwell, became courtside fixtures at the Summit. “They really built their relationship through the team,” said Fertitta’s middle son, Patrick. “That was date night for them.” The couple married in 1991 and had four children, all of whom grew up attending Rockets games with their parents.

“As hard of a worker as my dad is, the one thing that can get him to disconnect and relax is sports,” Patrick told me. “He loves being next to the guys, feeling like he’s a part of the team. For three hours a night every few days, he can get away from it all.”

This summer, as in 1993, Fertitta had serious competition for the Rockets. But he also had a few advantages he didn’t possess in the nineties. For one thing, he’s much wealthier, with an estimated net worth of $3.5 billion, according to Forbes, making him the 212th richest person in the U.S. and the 693rd richest in the world. His influence has grown as well. He’s become one of Houston’s leading philanthropists and serves as chairman of the University of Houston Board of Regents. And he has the visibility that comes from starring in a successful television show about to begin its third season in January.

Brown began receiving calls about the Rockets on the evening that he announced the sale. In the following days, there were media stories reporting that Fertitta, Olajuwon, and Beyoncé might be interested in buying the team. “There were a lot of people scrambling around, me included, to be part of the group,” said Houston trial lawyer and Texas A&M regent Tony Buzbee. “But everyone realized the one guy who would absolutely be in the deal would be Tilman Fertitta.”

There was also significant foreign interest, including from China, where the Rockets are a household name thanks to their former star, Yao Ming. The Rockets sale was a subject of intense speculation in the sports business world all summer, said Marc Ganis, an industry veteran. “There are very few marquee franchises in top markets that come up for sale. It rarely happens. As soon as I heard the news, I knew the number was going to start with a two.”

As in, $2 billion.

Fertitta, too, was convinced that the Rockets would sell for at least $2 billion, the benchmark set by former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer’s purchase of the Los Angeles Clippers, in 2014. “You had a lot of guys who kicked the tires and thought they could maybe pick the team up for $1.6, $1.7 billion,” he said. “A lot of people wanted to come in and do due diligence on the team. I understand business a little better, so I didn’t worry about the team . . . What’s the difference if the team makes $40 million a year or $80 million? You’re talking about something you’re going to pay $2 billion for.”

While his rivals’ accountants pored over the Rockets’ financial statements, Fertitta was huddling with his Landry’s executive team, running the numbers again and again, trying to figure out how the hell they were going to raise that $2 billion. Fertitta didn’t even bother to call Brown, the Rockets CEO and his longtime friend, until three days after the sale announcement, leaving Brown to wonder just how interested Fertitta really was. This was strangely passive for a man who is notoriously relentless in his business dealings.

By Saturday, August 5, nearly three weeks after the announcement, Fertitta still had not submitted a bid, and Brown was running out of patience. He had received about a dozen offers that he considered serious. It looked from the outside as if Fertitta might be letting his chance at the Rockets slip away. Around nine that morning, Brown, who was dropping his daughter off at college, took a break to give Fertitta a call.

“Listen, I just want to be transparent—you’re behind,” Brown told him. “There are a number of people who have already submitted actual offers. If this is something you truly want, then I would recommend you submit your offer as quickly as possible.”

For a few seconds, Fertitta was uncharacteristically silent. Then he spoke.

“I’ll have you an offer by tonight,” he replied. The chase was on.

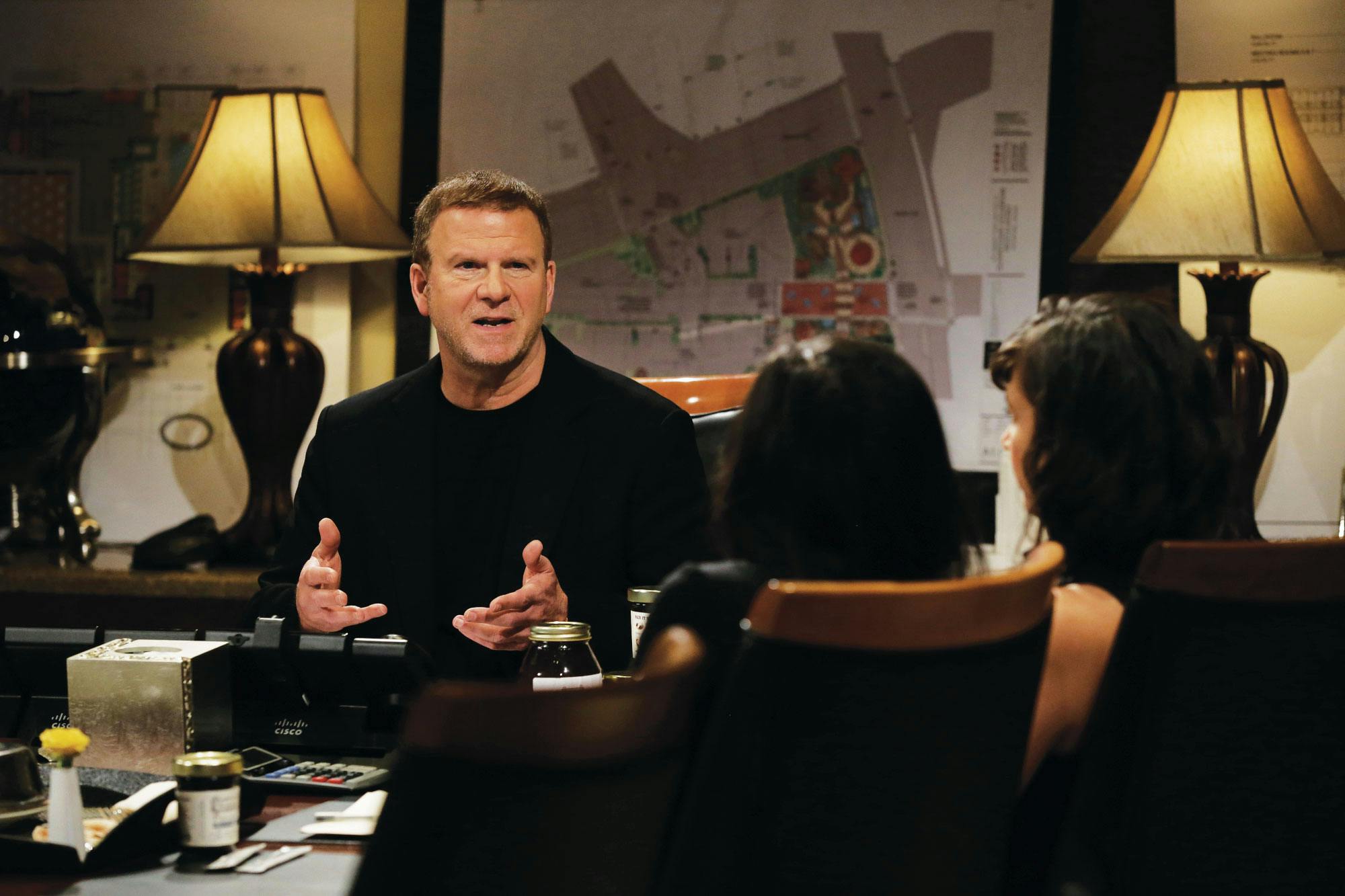

Fertitta isn’t just an aggressive deal-maker in real life; he also plays one on TV. In each episode of Billion Dollar Buyer, Fertitta visits two small businesses that hope to supply a good or service to his restaurant, hotel, and gaming empire. After testing the product for himself and then putting it through a trial run at one of his properties, Fertitta summons the business owners to his Houston boardroom, where, in the episode’s dramatic denouement, he announces whether he’ll be placing an order with one, both, or neither of them.

Fertitta told me that, in contrast to similar shows, like The Apprentice and Shark Tank, which emphasize conflict and drama, he tries to mentor the businesspeople he meets rather than humiliate them. This turns out, in practice, to be a distinction without a difference. A typical episode of Billion Dollar Buyer involves Fertitta meeting business owners, eviscerating their product and business plan—occasionally reducing them to tears—then informing them exactly what they must do if they want to become his suppliers. It feels more like hazing than mentoring, and the businesses featured on the show seem chosen as much for their dramatic potential as their commercial viability.

On a Friday in September, Fertitta flew to Austin to shoot a scene at the Lakeway office of SPI Outdoor Products, which had developed a high-tech outdoor dining table, the BellaBreeze, that featured USB ports and a miniature HVAC system capable of blowing cold air in the summer and hot air in the winter. To Fertitta, who owns dozens of restaurants in places like Chicago and Boston, where patios can be used for only part of the year, the invention seemed intriguing.

Company CEO Bill Molnar and vice president Roy Prosise were hoping to sell five hundred tables to Fertitta at $2,900 each. They had set up a prototype for him to try on a Lake Travis marina near their office. But almost as soon as he sat down he started noticing problems. Holding his hands up to the vents embedded in the center of the table, Fertitta could feel a strong airflow, but when he leaned back in his chair, he could barely tell it was blowing. “I feel like this is good for heating or cooling my food, but I’m not feeling much,” he told Prosise and Molnar. Fertitta then realized that the air wasn’t getting colder—it was getting hotter. “Is this an AC unit or a portable sauna?” he asked.

“Something has gone awry,” Molnar mumbled, while Prosise, panicking, got down on his knees under the table, removed one of the panels that concealed the HVAC unit, and tried to figure out what was wrong. “You gotta be shitting me,” Prosise muttered to himself as Molnar rattled off a series of possible reasons for the malfunction, ranging from the AC compressor freezing up to unexpected “swirling air” on the marina.

“This is the item that’s going into production in 120 days with five hundred units?” Fertitta shot back, his voice rising in anger. “The worst thing you can do is go to market before the product is perfected.”

On camera, Fertitta told Prosise and Molnar that he would give them a second chance, allowing them to conduct a test run with the BellaBreeze on the patio of his Grotto restaurant in Houston. If the test was successful, Fertitta said, he would consider placing an order. During a break from shooting, Fertitta was more scathing, telling the show’s executive producer, David Tibballs, that the table seemed like a “science fair project.” Plus, he said, it just looked cheap.

After shooting wrapped up, we piled into a GMC Yukon for the fifteen-minute drive to the airstrip where Fertitta’s helicopter was waiting. He was clearly impatient to get back to Houston. “You can go faster,” he told the driver. The SUV dropped us off at the airstrip, part of an upscale residential development for owners of private planes, and we climbed into the helicopter’s soundproofed, wood-paneled cabin. As we began to lift off, though, he suddenly realized he didn’t have his iPhone.

“Wait, wait!” he screamed through the partition at the two pilots. As the helicopter settled down, its blades still spinning, he rummaged furiously through the pockets of his windbreaker, then threw it onto the floor in disgust. He repeated the operation for the several tote bags lying at his feet.

“I grabbed a bunch of shit, and I didn’t grab my fucking phone,” he said in self-reproach, slumping back into his seat and snatching up a handful of grapes from a nearby fruit basket. “I’m aggravated.” He popped a grape into his mouth and gestured brusquely at my own iPhone. “Can I borrow that?”

It wasn’t really a question, so I handed over the phone. After making a few calls, Fertitta gave it back and told me, somewhat sheepishly, that the SUV’s driver was on his way back with the phone, which he had apparently left on the passenger seat.

We spent the next few minutes in tense silence, Fertitta binge-eating fruit and both of us looking warily out the windows at the growing crowd of onlookers that had gathered in a perimeter around the helicopter, its blades still spinning; the piercing, high-pitched whoop-whoop-whoop-whoop had driven residents of nearby houses onto their lawns. Many had their own phones out, recording us.

Finally the SUV pulled up and the driver handed off the phone to the pilot, who opened the cabin door and passed it silently to Fertitta. The pilot closed the door, climbed back into the cockpit, and we took off into the nearly cloudless sky, the gawkers below receding into the distance, still recording us.

On the evening of August 5—just hours after Fertitta had promised to send in his offer—Tad Brown was out to dinner with his daughter when he checked his phone and saw an email from Fertitta. Attached was a four-page letter of intent outlining Fertitta’s offer for the Rockets: $2.2 billion, the most anyone has ever paid for a North American sports team. The letter also included an unusual guarantee, written in bold type: if Fertitta couldn’t close the deal, he would pay Alexander $100 million in cash.

“I knew that raising the money was not going to be an issue for me, because that’s all I had been working on,” Fertitta explained. “So I put up $100 million. I don’t close, I can’t raise the money, you keep my $100 million. Nobody will do that. That’s what separates me from everyone else.”

After submitting the bid, Fertitta hoped his tenacity would help make the difference. He launched an all-out effort to persuade Brown and Alexander to accept his bid. “Myself, my team, my sons worked it day and night for weeks,” he told me. “We just did whatever it took to make sure we won it.”

The effort did not go unnoticed by Rockets management. “Once he kind of lasered in on what he needed to do, he without question wanted it more, went after it harder, put everything in place faster, and really went out and took it,” Brown said.

On Thursday, August 24, Fertitta was on his yacht in Los Angeles’s Marina del Rey. He was in town to film an episode of Billion Dollar Buyer, but a severe cold had forced him to cancel shooting for the day. When Brown called him that morning, Fertitta could sense that the Rockets executive had something important to say. Then Brown broke the news: Alexander had chosen Fertitta’s $2.2 billion bid and wanted to move forward to finalize it. “He was very emotional,” Brown recalled. “It was one of those days for him and his family where they realized their lives would change forever. And that was the moment for me when I realized we had the right guy.”

Amazingly enough, Fertitta’s $2.2 billion wasn’t the highest offer the team received; at least two rivals offered more money, Brown said. In the end, though, Fertitta’s hometown connections, relentlessness, and ability to close the deal quickly proved decisive. (Alexander had insisted that the sale be finalized before the start of the new basketball season, in October, so that it wouldn’t be a distraction for the players.)

For Fertitta, the Rockets purchase represented the capstone to a career that began in the sixties in his father’s Galveston restaurant, Pier 23, where he grew up peeling shrimp after school. He learned the business from the bottom up, quickly demonstrating a savant-level aptitude; in his early teens, he fired two waiters for getting into a fight, then took over their stations himself. “At fourteen years old, I knew what to do, and I told my dad to go home and let me run the restaurant,” Fertitta told me. “I knew the front of the house, I knew the back of the house. That’s how confident I was.”

Two branches of his family, the Maceos and the Fertittas, have deep roots in the more colorful side of Galveston history. Two of his great-great-uncles, Sicilian immigrants Salvatore and Rosario Maceo, operated the island’s notorious Balinese Room, a nightclub and illegal casino that featured entertainers like Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, and the Marx Brothers. Fertitta’s paternal grandfather and great-uncle helped run the Maceos’ casinos.

After two desultory years of college, including two semesters at the University of Houston’s Conrad N. Hilton College of Hotel and Restaurant Management, Fertitta dropped out and embarked on an unlikely series of commercial ventures, including a women’s clothing store, a vitamin retailer, a construction company, and—most lucrative of all—an arcade-game distribution business. But he spent freely, and during the economic crash of the eighties, his companies managed to run up more than $10 million in debt. Twenty-five of his creditors sued him. Thanks to an aggressive team of lawyers led by Steve Scheinthal, who’s now the general counsel of Landry’s, Fertitta was able to restructure his debt without having to declare bankruptcy.

In 1986 he purchased the Louisiana-born brothers Bill and Floyd Landry’s stake in two Houston-area restaurants: Landry’s Seafood Inn and Oyster Bar in Katy and Willie G’s in the Galleria area. After buying out his sole remaining partner the following year, Fertitta launched an aggressive expansion campaign. His two new Landry’s locations in Houston failed, but he had more success farther afield, opening up profitable outposts in Galveston, Kemah, Corpus Christi, and San Antonio.

Having grown up in his father’s restaurant and worked at several others, including a stint at another restaurant owned by the Landry brothers, Fertitta knew all the tricks of the trade; he’s been known to dump out the trash in his kitchens to see if the busboys are throwing away tableware. His obsession with consistency and detail helped his restaurants catch on with middle-class customers looking for affordable family dining—something nicer than Red Lobster but less fancy than a white-tablecloth place.

To finance further expansion, Fertitta took Landry’s public in 1993, raising $24 million on the stock market, which helped fund a decade-long buying spree: Joe’s Crab Shack (1994), the Crab House (1996), Rainforest Cafe (2000), Chart House (2002), and Saltgrass Steakhouse (2002). In 1997 Fertitta bought every restaurant on the Kemah waterfront he didn’t already own, erected a Ferris wheel, and rechristened it the Kemah Boardwalk. In 2003 he transformed two former municipal buildings on the banks of Houston’s Buffalo Bayou into the Downtown Aquarium, complete with yet another Ferris wheel and, controversially, a caged group of white tigers. (Animal rights groups have long criticized Landry’s treatment of the tigers. In September, an advocacy group filed suit against the company in federal court, alleging that Landry’s treatment of the tigers violated the Endangered Species Act. “Most troubling, the tigers have not been outside for more than 13 years,” according to the suit. Landry’s has long defended its treatment of the tigers, and Scheinthal recently told the Houston Press that the company plans to expand the exhibit to include an outdoor area.)

Ever since his first two Landry’s restaurants went bust, almost everything Fertitta has acquired or built in the hospitality industry has turned to gold. He’s the King Midas of middlebrow dining. Critics often complain about bland, mediocre food at his restaurants, but Fertitta doesn’t seem to care. “You’re talking about a small group of people who, just because I have a lot of chain restaurants, think the food is no good,” he told me. “It doesn’t bother me at all.”

But Fertitta also courted a more rarefied clientele. He purchased the San Luis Hotel in Galveston from developer and oilman George Mitchell in 1995. In the early aughts, he bought a string of poncy expense-account restaurants in Houston—Pesce, Brenner’s, Grotto, and La Griglia—and opened Vic & Anthony’s Steakhouse, which he named after his grandfather and great-uncle. In 2005, Fertitta followed his illustrious forebears into the gaming industry by purchasing the then-59-year-old Golden Nugget casino, which had locations in Las Vegas and Laughlin, Nevada. He has since opened new Golden Nugget resorts in Lake Charles, Louisiana; Biloxi, Mississippi; and Atlantic City.

In 2008, the Great Recession hit the hospitality industry hard. Americans who lost jobs or saw their net worth crater along with the housing market reined in their spending. Though his restaurants suffered like everyone else’s, Fertitta also saw an opportunity to take back full ownership of Landry’s while the company’s stock price was down. It was the same strategy he had used time and again to acquire struggling restaurant chains—except that this time the struggling chain was his own. “If you go back and look at the ’90s, 2000s, every time there’s been a hiccup [in the economy], that’s when I’ve been able to feast on other companies,” he told me. “That’s when I grow. Because companies are not run well, and they panic. I don’t panic.”

In 2010, after a bruising two-year campaign fought in the courts and the media, Fertitta finally persuaded reluctant Landry’s shareholders to sell out for $24.50 a share, which worked out to a price of $1.4 billion when you include the $700 million in debt that Fertitta also assumed. Costly? Perhaps. But today Fertitta stands alone as the company’s chairman, CEO, and owner. With no stockholders to answer to and no partners to consult, he has total control of Landry’s, giving him the freedom, as he once told Forbes, to “do whatever the fuck I want.”

Taking Landry’s private sent Fertitta’s net worth soaring. He cracked the Forbes 400 list in 2012 with an estimated fortune of $1.6 billion, making him the world’s first billionaire restaurateur. He now owns a 164-foot yacht, two planes, four helicopters, and an $18 million, 25,548-square-foot mansion situated on more than five acres of carefully manicured grounds in Houston’s River Oaks neighborhood. “I knew what I was doing,” he said about taking Landry’s private. “You lose the daily, weekly, and monthly liquidity of being able to sell shares whenever you want, but if you have a long time horizon, it’s 100 percent the best thing to do. Most people don’t know how to financially engineer it.”

Fertitta’s newest project is his most ambitious, and one of his most expensive to date: a $300 million, 36-story tower—currently under construction in the Houston Galleria area, next door to Landry’s corporate headquarters—that will house a hotel, office space, residences, restaurants, and retail shops. It’s known as the Post Oak, and it’s scheduled to open in the first quarter of 2018. Fertitta considers the handsome limestone-and-glass tower a legacy project. “This will be in my family a hundred years, just like the San Luis,” he told me.

On a recent evening, Fertitta and Landry’s executive vice president of development, Jeff Cantwell, gave me a hard-hat tour of the construction site. We started in the hotel lobby, where we gazed up at a rig that will eventually support a $1 million Swarovski crystal fixture. Fertitta and Cantwell then led me past a future wine cellar, a two-story Rolls-Royce dealership, and a hangar-size ballroom, which Fertitta declared would be the finest in the city. Fertitta oversaw every detail of the project, from the height of the check-in desk to the design of the hotel minibar. As we walked down one corridor, he stopped to stare at a section of the wall paneling.

“Jeff, I think this is wrong. It’s not like it is downstairs.”

He pulled a rubber-banded roll of cash and credit cards out of his pocket, slid out a black American Express card, and placed it against the panel.

“It looks about a sixteenth of an inch off,” he told Cantwell, who nodded in agreement.

Was this being staged for my benefit? Can the human eye actually detect such a minuscule discrepancy? Whether or not it was a put-on, the message was clear: Fertitta cares about the little things.

“I understand every aspect of this business,” he told me. Landry’s operates more than six hundred restaurants, hotels, and casinos around the world, and Fertitta insisted that he could do every job at every one of them.

“Even the chef’s job?” I asked.

“Absolutely,” he replied. “I’m not a chef, I don’t know the total science of putting it together, but I can walk into any of my kitchens, look at the food, and tell you what’s right or wrong with it. And if something isn’t right with it, I can tell you why it doesn’t look how it’s supposed to. I can tell you if the oil wasn’t hot enough, if the skillet wasn’t hot enough, if the oil hasn’t been changed.”

In Houston, to say that a restaurant has been “Fertitta-ized” isn’t usually a compliment. The word evokes Fertitta’s well-documented history of sanding down the rough edges of beloved restaurants to create what some consider an insipid conformity. He infamously changed the menu at one of his first restaurants, Willie G’s, from Cajun to seafood and steak, later explaining that “Cajun food was a fad.”

But Fertitta takes pride in the neologism, seeing it as a testament to his obsession with quality control. “All my haters love to say, ‘Oh, his food sucks’ or whatever. But we’re consistent. The hot food’s hot, the cold food’s cold, the music’s right, the property’s clean. You don’t have burned-out lights, you don’t have cigarettes by the front door, you don’t have trash in the parking lots. You know what you’re going to get.”

On Friday, August 25, the day after Alexander accepted Fertitta’s bid, Hurricane Harvey made landfall near Rockport. Fertitta was stuck in L.A., shooting an episode of Billion Dollar Buyer. During the storm, he continued to work the Rockets deal, coordinating by phone with his Landry’s management team in Houston, many of whom drove through high water to reach the office each day. Brown, the Rockets CEO, worked all through Harvey as well. Forced to evacuate from his home in Kingwood, which had lost power and looked as if it might flood, Brown drove to Dallas and checked into a hotel room, which became his office until the water receded later in the week.

A contract was soon signed, but Fertitta still needed to raise $2.2 billion—no easy feat, even for one of the world’s thousand richest people. Alexander agreed to finance $275 million of the deal. Fertitta then borrowed $250 million against the value of the Rockets, the maximum allowed by the NBA, and kicked in $300 million of his own money, but that still left him $1.375 billion short.

Rather than selling equity in the company, which would have meant giving up full ownership, Fertitta decided to make up that difference by issuing corporate bonds and bank debt. It’s a strategy he’s used time and again since taking Landry’s and the Golden Nugget private, in 2010. “He has a very, very good reputation and track record in the bond market,” said Rich Handler, the CEO of Jefferies, which served as the lead underwriter of the bond sales. “We’ve done a lot of deals with him, and the lenders have made a lot of money.”

Casting a shadow over all of Fertitta’s presentations were Hurricanes Harvey and Irma. About half of Fertitta’s properties are in coastal cities, and 40 percent of those are right on the water. (He learned long ago that seafood restaurants perform better when they’re located near water, even if the food they serve was caught halfway around the world.) “Did he likely pay a little more in interest because of what happened with the natural disasters?” said Seth Meyer, a portfolio manager at Janus-Henderson who bought bonds in the sale. “I’d probably say yeah. Lenders are thinking he has a lot of exposure [in] Houston. Lake Charles was hit. Biloxi was hit. Florida, where he has a lot of units, was hit.”

In a warming climate, such disasters are likely to become more frequent and more destructive; Houston alone has suffered three “five hundred year” floods in as many years. That’s clearly a risk, Meyer admitted. “But where people live dictates where the restaurants are. As long as people continue to live in coastal cities, restaurants will continue to be there.”

Over the course of less than two weeks, more than a hundred institutions bought bonds, including Citibank, Deutsche Bank, Fidelity, and Putnam. He secured the financing he needed, and because he never took on any partners in the deal, the Rockets are all his.

In the wake of the sale, Rockets fans began speculating about what a Fertitta-ized basketball team would look like. Would Fertitta be a highly visible owner, like the Dallas Mavericks’ Mark Cuban, who sits behind the team’s bench during games and likes to lean in on huddles? Or would he try to play general manager, like Dan Snyder, whose compulsive meddling has made the Washington Redskins one of the losingest teams in pro football?

Despite his reputation as a micromanager, Fertitta said he has neither the time nor the inclination to oversee the team’s day-to-day operations. “The Rockets are a very well-run organization. I don’t see any major changes. I think you’ll start seeing tweaks in the years to come, but if anyone’s looking for some drastic changes, they’re not going to see them.” Still, can the man who prides himself on being involved with even the smallest details of his businesses resist doing the same with his new prized purchase?

In the short term, the team doesn’t need drastic changes. The Rockets have made the playoffs every year since 2013. Their star, the extravagantly bearded James Harden, is a perennial MVP contender who just signed a four-year contract extension. He’s now playing next to point guard Chris Paul, a nine-time All-Star the team acquired from the Clippers over the summer. (When I asked what advice he would give Fertitta, Cuban was succinct: “Waive James Harden and Chris Paul.”) The team seems poised to make a deep playoff run this season, maybe even contend for the championship.

Then again, maybe not. Standing in their way are the Golden State Warriors, winners of two of the past three NBA championships and widely considered among the best teams in history.

“There’s no doubt that Golden State is, on paper, a superior team, one of the greatest teams ever,” Fertitta said. “And I think the Rockets are the second-best team. But an injury here and an injury there, or a three-point shot at the end of a game—it’s amazing what can happen.”

He would, of course, love to win a championship this year, just as Alexander did in his first year as Rockets owner. As a businessman, he’d also like the team to make him money, and he has every expectation that it will. Fertitta is bullish on the NBA. Unlike football, baseball, or hockey, basketball is played all over the world. And with the NFL facing an ever-ramifying concussion crisis and Major League Baseball trying to speed up games to appeal to a younger audience, basketball increasingly seems like the sport of the future. At a time when the NFL’s viewership is falling, ratings for this season’s opening-night NBA doubleheader were up 53 percent over last year.

Then there’s the thorny issue of the recent National Anthem protests, which some observers partly blame for the NFL’s declining ratings. The NBA has long required players and coaches to stand for the anthem—an example, Fertitta said during a recent appearance on CNBC’s Power Lunch, of “how forward-thinking the NBA is right now.” Harden, who joined Fertitta briefly on the show, seemed to agree, arguing that players can express themselves in other ways.

But there are still uncomfortable racial dynamics in the league. At one point during the show, CNBC host Brian Sullivan referred to Fertitta as Harden’s “new owner.” He seemed poised to use the same locution again before catching himself and rephrasing. In a league where about 75 percent of the players are African American, there is still only one black majority owner, Michael Jordan, of the Charlotte Hornets.

Fertitta, naturally, would prefer to think of himself as part of the team. It’s why he still sits courtside during games rather than insulating himself in a luxury box as many other owners do. In his mind, he’s still just the ultimate Rockets superfan. Owning the team, however, does seem to have fulfilled some kind of deep psychological need. “It’s definitely more emotional than financial,” he said of the purchase.

“This was something that was absolutely important to him and his family,” Brown told me. “He made very clear to me that this was the property, the purchase, that he and his family wanted for the rest of their lives.”

“Generational” seems to be one of Fertitta’s favorite words. Over the course of our interviews he used it to describe the Post Oak, Landry’s, and now the Rockets. Referring to his children’s love of the team, he told me that this was “one group of kids who will never sell.” The Rockets have served as their connection to a hard-charging, workaholic father who, it must have seemed to them growing up, was always either traveling or at the office.

“We really built our relationship with our dad in a lot of ways through sports,” Patrick told me. “Sports is something that’s been a glue for us forever.”

For his part, Fertitta sees the Rockets as perhaps his most lasting legacy, something that will stay in his family in perpetuity. “You know, basketball stars come and go,” he told me. “The one continuity you’ll see over the next hundred years is that, when I’m gone, the Fertitta name will still be attached to this team.”

Michael Hardy is a writer-at-large for Texas Monthly.