Shithouse Shortie, my sixth-grade boyfriend, didn’t show up for our forty-fifth high school reunion in Texarkana, and I’m not forgiving him, because I had a column to write and I knew that his nickname and his business card—which once advertised his portable toilet–leasing business with the phrase “Your shit’s my bread and butter”—would stir the muses a bit. Three other guys I’d hoped to dance with didn’t appear either, but that was because they were dead.

My earliest childhood friend, Frances, and her California spouse, Michael, accompanied me on this weekend wallow. Michael said he always regarded his trips with Frances to Bowie County as archaeological/anthropological digs. We didn’t do much digging, but we did make a couple of cemetery stops, not to visit old boyfriends but to be certain our parents’ graves were being properly tended. Michael admitted that the only East Texas phrases he had mastered through the years were “Hy’re yew” and “Are you saved?”—both of which he found mystifying, his being a Californian and a Roman Catholic. I promised to tutor him. I can slip back into my hometown vernacular as easily as I can consume the entire jumbo platter of fried catfish at Lee’s, the first scheduled venue for our reunion. My husband claims that if I stay for more than a weekend, I return to Dallas saying, “Where you parked at?”

Our native tongue was not the soft Southern vowels and charmingly dropped r’s of Lady Bird Johnson’s but the flat i that my children loved to imitate by repeating the city’s advertising slogan: “Texarkana Is Twice as Nice.” (Frances and I spent a high school summer at Northwestern University, outside Chicago, where our i’s and our use of the pronoun “y’all” almost required a translator in a nest of overenunciating Yankees.) We were among the last segregated classes. The only black children we ever knew in our town were those who came with their mothers to clean our houses. The men in my class seem to recall some vacant-lot sports encounters but no formal introductions. Our restaurants and movie houses were segregated as well.

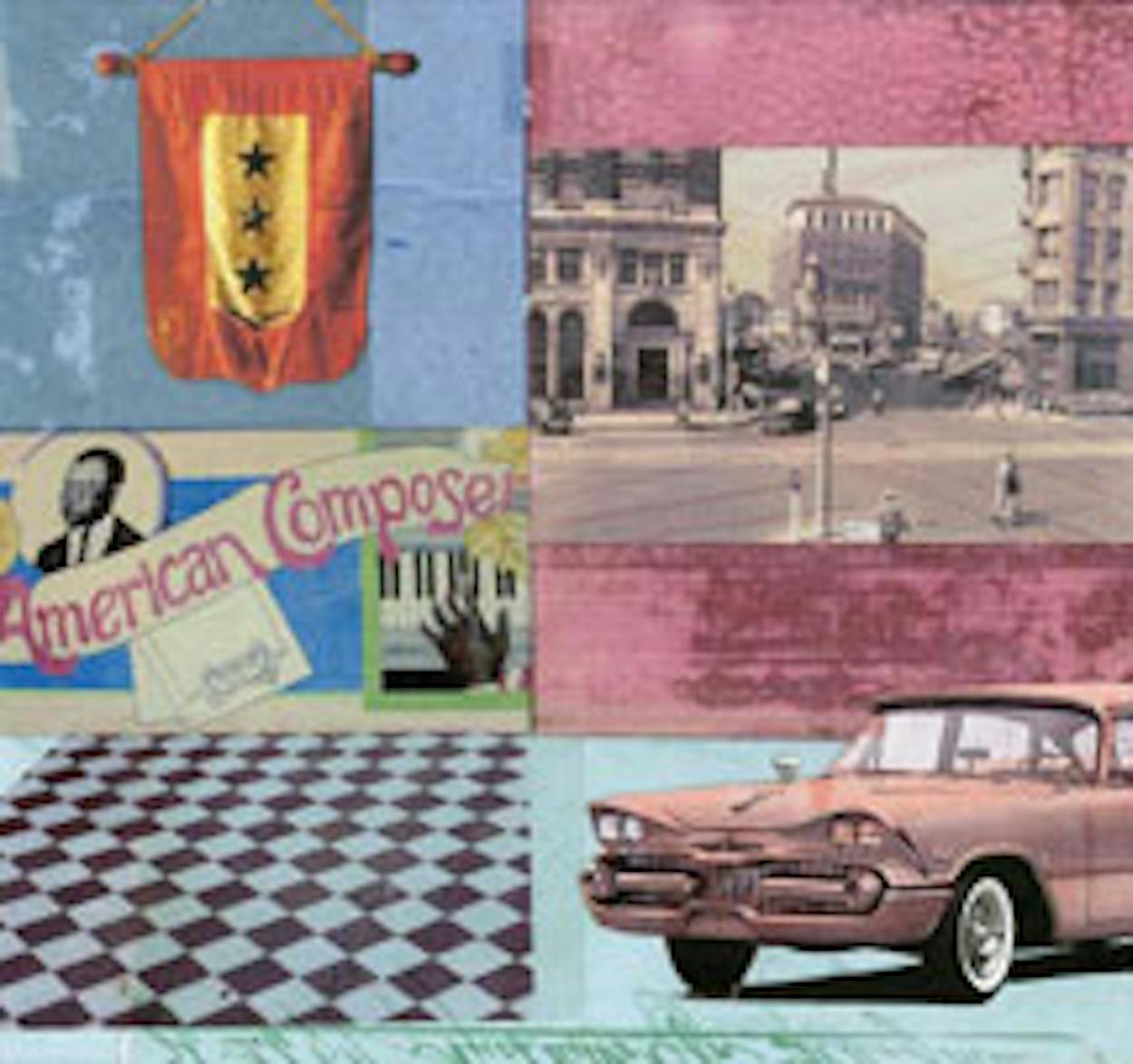

One of the nostalgic events of our reunion included a visit to a favorite hangout, the Paramount Theater, which, after becoming a third-run movie house with sticky floors in the late seventies, was restored to its original twenties grandeur and reopened as the Perot Theatre in 1981. The Paramount was our destination of choice for Sunday afternoons after church and lunch at Bryce’s Cafeteria. We never thought to admire the checkerboard marble foyer where we bought our tickets. For that matter, we hardly noticed the movie. We were bent on seeing our friends and tormenting the gray-haired matronly woman with the big flashlight who threatened us with expulsion every week. Not one member of my class recalled the separate entrance to the left of the front door. During our reunion tour, I took a seat in the balcony where our black counterparts had been allowed to sit. We were oblivious of their presence. We were so noisy; they must have been very quiet. I exited the nearest stairway hoping to make my way to the ladies’ room and discovered that my descent offered no access to the mezzanine or the first-floor space where the concession stand once stood. No restroom? No popcorn? Not even a separate-but-equal water fountain.

I’d like to call my class the Second-Best Generation. Most were the children of World War II vets. We are one year too old to be classified as bratty baby boomers. The frugal habits ingrained in our parents by the Depression were a constant in our one-bathroom homes. Frances and I furnished our dorm room at the University of Texas with bedspreads purchased with S&H Green Stamps. At Texas High School we were thoroughly indoctrinated with Cold War “Better Dead Than Red” ideology and the heroism of the Confederacy. Questioning the politics or religion of our parents was as foreign to most of us as worrying about the content of the hot dogs we consumed at the local Dairy-ette. Many of our male classmates served in Vietnam. One remained in the Far East and now runs luxury hotels in Thailand; another is a medical researcher in Canada who drove to the reunion just to get a feel for his other country. Our female salutatorian just retired after teaching school for 35 years. A retired dentist still fixes children’s teeth in Honduras with a church mission. Frances has been saving the environment most of her life and now serves on California’s water resources control board. Judy, unforgettable because of the tap dance routines she and her sister performed for every talent show and civic group in town, became an ordained Presbyterian minister. Nearly a third of our class resides in Texarkana. Several told me that they returned because there was no one else to take care of their aging parents. We are a useful and dutiful bunch.

One classmate remarked that she thought this was the best reunion ever because all barriers were down. Hearts broken in high school have now been either bypassed or, in at least one case, replaced. To me, the whole weekend seemed to flow with effortless goodwill. If there were perceived barriers, they were never very high. Life in our town in the fifties and early sixties didn’t offer many ways to show off. Well, the Dillard’s department store heir was regularly transported by a chauffeur named Cooper, and the plumber’s daughter, a blond majorette, drove a pink Thunderbird, but most of us shared our family’s lone automobile. One classmate recalled being mightily impressed that my family’s little house on Pine Street had wall-to-wall carpeting. I hope he noticed the single window-unit air conditioner we turned on for company in the living room.

While we exchanged ridiculous compliments about how no one had changed, it was impossible to ignore the changes in our hometown. My house was torn down in 2000. Our old high school is vacant. What we called “downtown” has been dead for years, and the Beverly neighborhood, where so many of us grew up, has become crime ridden and sad, but the town thrives and grows north in places we knew only as country roads for “parking.” Chain restaurants, fancy medical centers, and new businesses line the I-30 highway, built after we graduated. A Starbucks has opened, although it has to compete with the free coffee at the First Baptist Church’s coffee ministry. I even found a Sunday New York Times to read on the trip back to Dallas. The cashier said, “That’ll be a dollar.”

“No,” I said. “This is the Sunday Times. It’s five dollars.”

She looked aghast. “Five dollars for a newspaper? I sure hope it’s got lots of good coupons.”